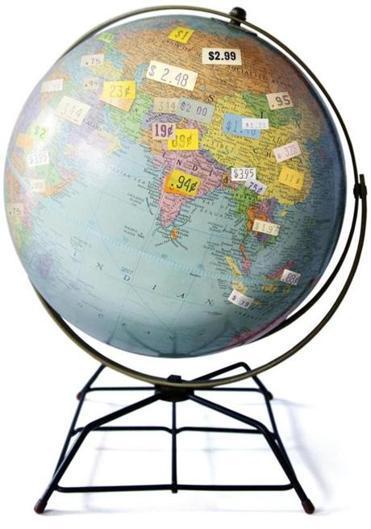

Let’s Make a Deal: Emerging Global Trumpism

Illustration: ROB DOBI FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

DONALD TRUMP came into office promising that his sharp deal-making skills would revolutionize US foreign policy. It sounded like bluster — not much of a change from Trump’s predecessors, who also believed they were negotiating deals for their American constituents.

To many ears, Trump’s vow also sounded unprincipled. Even though American relations with the rest of the world always have had a transactional element, Washington’s overarching goals for most of its history have been broad and moralistic, with a premium on long-term security and prosperity.

Meanwhile, Trump’s initial moves — dispensing with the niceties of alliances and accords, breaking with normal diplomatic practice, avoiding the theater of give and take before critical decisions are made — seemed to reflect his impulsive temperament, not some larger theory of how to promote the national interest.

But after a hectic half-year during which Trump has thrown the US diplomatic handbook out the window, the rough outlines of Trump doctrine are starting to emerge. Even the president’s most vociferous and worried critics (myself included) ought to entertain the prospect that there’s a method to the recent madness in international affairs. Maybe Trump’s wholesale reengineering of America’s approach to the world isn’t just the accidental consequence of a White House managed by chaos theory. Maybe Trump really has an intentional plan to transform the world order itself.

In recent weeks, Trump has begun to articulate what “America First” deal-making means on the global stage. Announcing his withdrawal from the international climate change accord, he emphasized that he represents “Pittsburgh, not Paris.”

Still more telling was his speech in Saudi Arabia, where he assured a select group of pliant allies that America would stop lecturing about rights and responsibilities . He also signaled he would support an unpopular war on Yemen, and take sides with Saudi Arabia in its other neighborhood squabbles with Qatar and Iran, so long as Saudi Arabia adopted America’s counter-terrorism priorities and continued its historical support of the US defense industry. While the president appears to have exaggerated a colossal $110 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia, the contours of Trump’s deal were clear.

Bald nativism colors the president’s rhetoric, but a clear ideology underlies it. Trump’s government will no longer shoulder a superpower’s burden of maintaining a world order; it will leave that task to others, and reap the short-term windfalls that might come with its collapse. Transactions will no longer be a tactic but the goal itself; each interaction must be a win for the United States — no more short-term compromises to achieve long-term goals. His predecessors made soaring appeals to the aspirations of free peoples. Instead, Trump asks at each and every turn: “What’s in it for us?”

This approach has several virtues for Trump. It can be explained on a bumper sticker, unlike more ambitious policies, which by definition are also more ambiguous. Its gain will come in measurable increments — big arms deals with a set price tag, big savings for American businesses no longer fettered in the international arena by rules and regulations — and not in hard-to-quantify metrics like stability, thwarted terror attacks, or democracy. Finally, the Trump approach is all about the now. How do you sell the American public on achievements like balancing a chaotic Middle East in order to stave off worse future violence, or protecting global shipping lanes, or upholding the NATO alliance?

Trump knows how to sell, and those of us who cherish the international liberal order (which until recently was a public good with profound bipartisan support) must worry that Trump’s foreign policy doctrine could win many adherents in the United States. His maneuvers will be understood to save money, dodge entanglements, and earn respect. So what if they actually do the opposite of the course of a full presidential term? Trump might build the most successful isolationist coalition in American history — in large part because he’s not a pure isolationist.

He wants to retreat from international commitments, and is willing to explode norms and institutions that make the world safer and richer, but he doesn’t want to retreat from the world itself. He’s happy to get involved, piecemeal and opportunistically, to make a buck here and a splash there. In Syria, for example, he has resorted to shows of force that Obama eschewed, twice bombing Syrian government targets, but he’s also shelved most of the sustained efforts by the Pentagon and State Department to actually manage or contain the Syrian conflict. This approach is not pure isolationism, but it is chauvinistic and indifferent to the needs of America’s allies (and the capabilities of its enemies to cause problems). Even as it harms America’s long-term standing and interests, Trump’s approach might well reap some short-term political wins that boost his popularity among Americans who have always been ambivalent about their superpower role.

FOR AT LEAST a century, America has conceived of itself as a “great power,” a primary beneficiary of a world order that it creates and upholds. During some periods of history, the global order is fluid, and it’s every nation-state for itself; in other, steadier times, there’s a firm taxonomy. Major powers set the terms for everyone, and reap most of the benefits. Most smaller powers accept the role of client, while a few maximize their interests by acting as spoilers, refusing the terms of the dominant order and risking a forceful response from the main powers.

Traditionally, America has pursued its interests with an eye on the long term, forgoing quick gains in order to consolidate positions that are perceived as best for American security and prosperity. Strategic patience has governed policy moves that are visionary as well as appalling. America made great sacrifices to rescue Europe during two world wars, and invested impressive resources through the Marshall Plan to ensure Europe’s post-war recovery into a wealthy zone of peace. America was equally long-sighted, if considerably less altruistic, in pursuit of Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine, which gave America a continental scale and ensured its domination of the Western Hemisphere, at an awful cost to indigenous Americans and the political autonomy of its neighboring countries. For good and ill, America was trying to control the game board, not merely to win the next round.

During the Cold War, although American foreign policy was complex, its central stated goal was straightforward: contain communism.

Trump’s emerging transactional doctrine harks back to that Cold War simplicity, after 25 years during which American presidents from both parties struggled to articulate precisely what American foreign policy stood for. The simplicity of Trump’s doctrine might feel familiar, but its innovation is to divorce America’s calculus from any core principle, moral or strategic.

American foreign policy has, since World War II, embraced liberal internationalism. The most important rival view has been classical realism, which would strip away moralistic layers of policy, like democracy promotion and humanitarian intervention, but would still exhort America to engage in promoting a stable world order that safeguards American interests. Realism — as practiced to some extent by states like Britain, Germany, Russia, and China — is less sentimental than liberal internationalism, but it invests heavily in cooperative international institutions, regimes, and agreements that preserve national interests. Meanwhile, from the margins, isolationists argue that America can protect itself without any truck with foreign powers and international accords.

Trump’s approach doesn’t fall neatly into these categories. It’s clearly anti-internationalist, but it’s not isolationist. Its closest historical analogue is the dangerously ambitious and agnostic approach of rising powers like Germany and Japan in the early 20th century, who were struggling to elbow their way into an international order that actively excluded them. There are few parallels of a strong, rich, established power resorted to destabilizing, relentless opportunism.

Unsurprisingly, Trump’s foreign policy doctrine is anathema to liberals, and it’s being executed in a haphazard and dangerous way. But it also draws on some real interests, often overlooked by liberal internationalists — like demanding that NATO allies shoulder their share of communal defense, or calling out Iran on its belligerence, or admitting what has already been a long-time practice: The United States will quickly overlook human rights abuses by countries that are willing to make lucrative deals with American companies.

A cynic might argue that there’s no real danger, since America’s foreign policy was often transactional in the past, and that Trump is simply saying in public what past presidents preferred only to discuss in private. But such insouciance overlooks the novelty of opportunistic transactionalism elevated from occasional tactic to core doctrine.

AS SOON AS America defects from international accords, others will follow suit or step in to fill the void. Some of these accords are informal, like America’s long-term commitment to promoting a balance in the Middle East rather than throwing its lot in wholesale with one side in a regional war. Trump has effectively thrown in his lot with one faction, dominated by Saudi Arabia, and the region is sure to witness an uptick in violence along with an increase in foreign involvement. Others, like NATO or the Paris Agreement, attempt to codify and lock in international cooperation in order to achieve ambitious goals that no single nation can accomplish alone but that benefit all. Without America’s support, it’s unclear whether such initiatives can survive, but by quitting (or in the case of NATO, potentially shirking) America stands to reap the short-term windfalls of the spoiler or the rogue state even if in the long-term it is likely to suffer the blowback as painfully as any nation.

The dangers abroad are manifold. They’ve begun to unfold in the Middle East, as states emboldened by Trump’s transactionalism already are overreaching. Israel’s settlements expand undaunted, and its political leaders (over the objections of its security establishment) are considering the merits of a preemptive war against Hezbollah in Lebanon, which would be disastrous for both Lebanon and Israel. Saudi Arabia, with Trump’s full blessing, is ramping up a war in Yemen that is only accelerating state collapse and terrorism, while pursing a collision course with Iran and any Arab state that deviates from the Saudi line (witness the recent excommunication of Qatar by Saudi Arabia and its partners).

On a global scale, China has quietly stepped into the gap left by the United States, making preparations for a vast web of infrastructure and investment that could make Beijing the key arbiter in East Africa, the Middle East, and parts of South Asia, as well as in the trade routes connecting those regions to China. Russia has asserted itself with new force in its sphere of influence. Rising nations around the world that have played along with international norms will reconsider destabilizing pursuit of self-interest over wider harmony, a state of autarchy and competition that could easily accelerate nuclear proliferation, a breakdown in international trade, and spikes in pandemics, famine and poverty.

A foreign policy that relentlessly maximizes immediate benefits for the United States might have a lot of appeal for Americans, even among constituencies that don’t like Trump. Its short-term results could play well in electoral cycles, before the toxic dividends come due.

At home, Trump’s approach will fan the flames of nativism and isolationism. In recent history, when America turned its back on the world and wished its responsibilities away, cataclysms forced it to reengage, first at Pearl Harbor and then on 9/11. The United States is the most powerful nation in the world. Its actions affect almost everybody on the planet, and, because we all live on the same planet, the actions of others affect the United States. America is dominant, but not all-powerful. It’s a giant on the world stage, but giants and predators do not live in splendid isolation. Their success and survival depend on an ecosystem. If America destroys that ecosystem, it too will suffer the consequences.