Nigeria is clamping down on its infamous email scammers. But it is law enforcement enough?

Lagos, Nigeria—Remember that Nigerian prince who contacted you a few months back, saying he needed assistance transferring his inheritance to the United States. If you would help him he would give you 10 percent of the total sum?

All he needed was your bank account details, and you’d be well on your way to riches—or at least on your way to seeing your riches siphoned off to an enterprising Nigerian.

Chances are, that email was written from a console somewhere in Festac Town, a quiet, ramshackle suburb of Lagos, Nigeria.

Here, a cluster of net café’s are rumored in Lagos’s press to be some of the last holdouts against a Nigerian federal crackdown on the country’s email scammers.

The Electronic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) of Nigeria has been putting email scammers in jail for the last two years. The commission has had some high profile victories. In October, it arrested 58 scammers in the city of Kaduna. The EFCC has invited journalists on a successful high-profile operation to apprehend a scamming ring and cooperation between international police agencies have foiled Nigerian-led rings that ran multimillion-dollar fraud schemes. In a 2007 report, the EFCC said it handled more than 18,000 advanced-fee fraud cases, a six-fold increase in just four years.

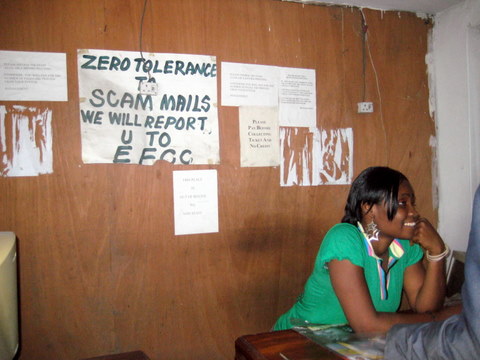

Now, even the net cafes in Festac are feeling the heat. Signs on the walls warn that the EFCC is watching and will prosecute scammers. Café managers are guarded.

A sign at Steadylink Communications warns against scamming.

In Lagos, Festac Town has the reputation of a crumbling neighborhood. It was once a posh, park-lined suburb that the Nigerian government built in 1977, during the country’s first oil boom, to house participants in the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. The festival drew tens of thousands from around the world to celebrate the achievements of the African Diaspora. Festac remained an upscale, desirable neighborhood until the 1980s.

But in the 1980s and 90s, Nigeria’s military government allowed Festac to deteriorate, and its wealthier residents left for newer neighborhoods. The area became a destination for youths hanging on to the bottom edge of Lagos’s middle class.

The history of Festac Town is a distinctly Nigerian one—a tale of squandered wealth and dashed potential. The idle, able youth who populate its Internet cafes, like Festac Town’s apartment buildings, were made for a future of far more promise.

When I walk into Steadylink Communication, a dimly lit, third-floor café with unfinished plywood cubicles, customers’ heads immediately turn. A foreigner with a notepad is not a common sight in this far-flung neighborhood. But my friend Kirk—a local journalist who has offered to show me around—tells me that a Nigerian in the same position would stir far more suspicion. People say that the EFCC has been sending undercover agents to shut down cafes.

It’s not clear to me, or to most anyone I talk to, whether the EFCC efforts have actually stopped small-time scammers from fishing for prey, or just driven them underground. The Internet Crime and Complaint Center (IC3), a U.S. federal body that tracks crime on the Web, actually reported an increase last year in the percentage of Internet crimes in the United States that had Nigerian perpetrators. For years, the IC3 has ranked Nigeria as the number-three source of Internet crimes in the world, behind the United States and the United Kingdom. The fact that Internet penetration in Nigeria is less than 7 percent seems to indicate that Nigerian scammers are particularly industrious.

The variety of scams is constantly growing. They prey not only on victims’ naïveté but also their greed—common scams include a request to facilitate a bank transfer of ill-gotten money. With a global pool to fish from—victims hail from richer countries on every continent—scammers only need a tiny percentage of people to take the bait.

The EFCC may not have stopped these scams, but the campaign has made a strong impression on café owners. Prince Kenneth Okonedo, the managing director of Steadylink, shows up in the café shortly after I arrive and starts feeding me talking points that sound well-practiced.

“We can monitor all the activity of computers in the café,” he tells me. “If we catch someone doing illegal things on their computers, we kick them out. If they come back, then we don’t serve them, because we know their face.”

Okonendo claims that has been happening a lot less frequently.

“There is always someone stubborn,” he adds with a smile. “If that happens, we can call troops to come and take them.” He says he has taken those measures only a couple of times, though he can’t describe a specific instance.

Café users I meet in Nigeria tell me that, since the EFCC campaign began, café staff peer over shoulders and monitor all the activity that occurs on their Internet Service Providers (ISPs). The EFCC is monitoring café activity, so the cafés monitor their customers. Okonendo confirms this, and tells me that the telltale sign of a scammer at work is that a vast amount of similar, template text will pass through the café’s ISP. This signals that someone is using cut and paste to send bulk spam, and a staff person makes a visit to the terminal.

Nextdoor at King’s Net Café, the manager on duty has a similar message to Okonendo’s. King’s café is more upscale. Natural light floods the room from three sides, there’s a pool table in one corner and an employee wearing a blue polo emblazoned with the café’s name serves soft drinks. The clientele—almost entirely young men—chat, surf and shoot eight ball.

Manager Ope Loye sits behind a laptop with a camera attached to it. A ask him if he knows the hit Nigerian rap tune “Yahooze”,in which singer Olu Maintain celebrates the high-rolling life of an email scammer. He laughs sheepishly.

Loye says no one is allowed to scam at his café. “Once they come in, we start monitoring, and if they are doing anything with cut and paste or anything like that, we ask them to leave.” That barely ever happens—fast wireless connections are not hard to get in Nigeria, and more email scammers are working from home now, he says.

But no matter how much the EFCC clamps down, the underlying reasons that Nigeria has gained the reputation of global Internet scam capital remain. Nigeria boasts a huge pool of relatively well-educated, jobless youth.

“You have a situation where you produce very educated graduates, people who are exposed well, aware of what’s happening and all of that,” says Ayo Olagunju, a software designer and financial analyst who grew up in Festac. “So you have educated people who are unemployed. And then maybe a friend says, Hey, you can make some quick bucks here. And you try it, and it works, and you get addicted.”

Fundamentally, Olagunju says, the email scam epidemic is the straightforward result of having highly skilled, Internet-savvy youths with no meaningful, legal opportunities to do work.

Olagunju would like to see government programs that help young scammers become legitimate entrepreneurs. He says Internet crime is just as damaging to Nigeria as it is to naïve foreign victims.

“I’m in the financial industry, and a deal I should just talk through over dinner, you have to word it and get lawyers to convince them you’re not fake,” he says. “It’s affecting people who are genuine.”

In their search for riches, he says, email scammers keep digging Nigeria into a deeper hole.