BY MATT LUCAS

Somewhere in the lost alleyways of Grozny, if you know the right place to go, you can hear Ruslan play his old records from before the wars. Zeppelin, Hendrix, Marley, the great jazzmen, the blues. According to Raisa Borshchigova, a Chechen journalist living in Grozny, Ruslan’s nameless bar is tucked away like an old speakeasy, its walls plastered with old record covers. The décor, old furnishings and posters, she said, are reminiscent of another time.

Somewhere in the lost alleyways of Grozny, if you know the right place to go, you can hear Ruslan play his old records from before the wars. Zeppelin, Hendrix, Marley, the great jazzmen, the blues. According to Raisa Borshchigova, a Chechen journalist living in Grozny, Ruslan’s nameless bar is tucked away like an old speakeasy, its walls plastered with old record covers. The décor, old furnishings and posters, she said, are reminiscent of another time.

The bar is often empty, Borshchigova said, and you can always get a good table near the stage where, one day, Ruslan hopes to have a jazz band play.

The music, Ruslan told her, helps him remember the happiest moments of his life, of a time before the wars destroyed everything.

The Second Chechen War began in August 1999. A month into the conflict, Borshchigova, who was then living in Grozny, returned to her family’s home in Davidenko, a small community 40 km away from the capital, on the Ingushetia border.

She was not the only one to abandon the city.

The advancing Russian forces, seeking to encircle Grozny, sparked a mass exodus of refugees from the Chechen capital, many fleeing towards the camps in Ingushetia.

Borshchigova said the column of refugees passing through her village seemed to stretch into the horizon. “There were thousands and thousands of people,” she said. “It was a huge line of twenty-twenty five kilometers of people.”

According to Borshchigova, the Russians closed the border crossing, preventing the refugees from crossing out of Chechnya.

“Nobody could go,” she said. “Everybody was waiting till they opened the borders.”

“The women from our village went there and they just brought some food for these people who were outside,” Borshchigova said.

“My mother went there.”

The mass of refugees made an easy target for the Russian aircraft. According to Borshchigova, the Russian planes struck the column of refugees fifteen times.

Though the numbers are disputed by Russian authorities, the BBC reported, after interviewing survivors, that approximately fifty people were killed in the bombings. Many more were wounded, including Borshchigova’s mother.

Her mother was taken to a hospital already teeming with the injured from the recent fighting around Grozny.

“It was the most horrible time of the Chechen War,” Borshchigova said. “The doctors couldn’t do anything.”

There were no medical supplies, or even electricity.

“So then,” she said, “my mother just passed away.”

The family retreated to their house in Davidenko, mourning their mother as best they could in the cramped quarters of the basement, which they shared with fifty other people.

A year after her mother’s death, Borshchigova went back to Grozny in September 2000 to return to her studies, which had been cut short by the Russian invasion.

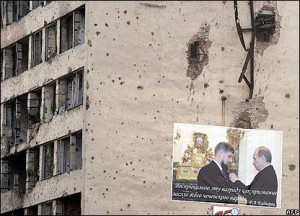

The city was destroyed, its skyline punctured by ruined buildings and crumbling facades.

A simmering insurgency had replaced the open combat of the initial Russian invasion.

“We were trying to study and we were attacked by Russians,” Borshchigova said. “Our university was always attacked by Russians.”

They came, she said, to take her friends. To torture them, to kill them, to burn the cars.

“One positive thing was that we could say everything that we were willing to say,” she said.

According to Borshchigova, they could demonstrate against the war and the human rights violations. People could go to the prisons to protest kidnappings and disappearances.

“Freedom of speech was still alive at this time,” she said.

It would not be for much longer.

“At about 2003-2004, the policy was the ‘Chechenization’ of the conflict in which there was a local proxy, which were clans that had come over to the Russian side, primarily the Kadyrov family,” said Andrew Kramer, a New York Times reporter in Moscow who has covered the Chechen conflict for more than a decade..

They moved quickly to stifle dissent and began asserting their power through a brutal mix of patronage and violence.

“Violent tactics such as abductions, disappearances and murder became the tools for governance,” Kramer said.

Borshchigova’s family would bear a heavy burden of this ‘governance.’

In January 2003, Borshchigova’s two younger brothers, Ibrahim and Rustam, were abducted from the family’s home in Davidenko. Masked soldiers came, as they frequently did, just before dawn. Roused from sleep in the darkness of the morning, the two boys were taken away.

“Since this day, we didn’t have any news from them,” she said. “They were just school boys.”

“We lost them and we weren’t together anymore,” Borshchigova said. “Our family was uncompleted.”

Only Borshchigova, her two sisters and their father remained.

Borshchigova left Chechnya in October 2006 to study in Paris and New York. She returned to Grozny three years later, in 2009, to a city transformed.

The reconstruction of the capital was well underway.

Russia is following, what C.J. Chivers, in an article for the New York Times, called “a two-stage formula: extraordinary violence, followed by extraordinary investment.”

Under Ramzan Kadyrov, Chechnya’s authoritarian President, the reconstruction of Chechnya has continued at a hurried pace.

After the war, Grozny, once described as ‘the most destroyed city in the world,’ was a hollow shell of its former self, marked by piles of debris and neglected buildings.

Such sights are disappearing now as the city sheds its war-time image, undergoing a dramatic renewal.

Portions of the city are beautiful now. Decaying apartment buildings have given way to open squares filled with flowers and trees. People might never realize that before the war, these were buildings, that people used to live here, Borshchigova said.

“I know that,” she said, “because I remember.”

People are trying to erase the consequences of the war, Borshchigova said, but it’s impossible.

Despite Russia’s announcement, in April 2009, that it was ending its counter-terrorism operations in Chechnya, peace remains elusive.

Borshchigova, who returned to Chechnya six months after the announcement, found a population subjugated by a Chechen government that had adopted many of the methods the Russian military had used during the wars. Counter insurgency tactics, according to Kramer, had evolved into political repression. The violence, far from being over, has escalated over the previous year.

According to the Caucasian Knot, a human rights website that tracks violent incidents throughout the North Caucasus region, Chechnya has experienced “a noticeable growth” in deadly attacks. Their most recent report states that almost twice as many people were killed in the year after April 2009 as in the year before.

Yet, according to Borshchigova, there are many Chechens who prefer life under Kadyrov because there is peace, or at least the absence of war. These people, she said, don’t care about their neighbors being attacked by security forces.

Many people think that life today is better, she said, but one day they will understand that they cannot live like this anymore.

For Ruslan, the comfort of an old record evokes memories of another era, reminding him of the time before the wars destroyed everything. The songs, fighting to be heard amongst the sounds of a revitalized city, beckon others to come in and sit for a while.

If Ruslan has his way, the records will soon give way to a jazz band.

He has a stage where the musicians could play, Borshchigova said, but there aren’t even any jazz bands in Chechnya anyway.

But one day there might be and people will go to Ruslan’s to listen and remember the time before the wars, when things were different.