By Stephen Schaber

My parents hate being bothered by the telephone- the ringing, the holding, the talking. When someone calls they rarely answer it. In fact, the answering machine picks up after two rings. I find it incredibly annoying.

They make an exception for my sisters and me. My routine when I call is “Hey guys, it’s me…anyone there?…Just…wondering…if…anyone…” in a slow drone. I hate being involuntarily broadcast to a potentially empty house. I have to wait a few seconds, sometimes half a minute, until I hear the sounds of my parents fumbling to pick up the phone- my mom on the cordless, my dad on the hands-free headset. My dad, a former professor of Software and Database Engineering with a doctorate in Quantitative Analysis, still hasn’t quite figured out how to use the hands-free headset. He’s had it for three years. This adds another 30 seconds.

“What’s up, Sonny?!” my Dad finally chirps.

“Hi, hi, hi! We’re here!” my Mom on the cordless, cheerful as always.

I called my parents frustrated in the first place. The answering machine ritual made me more so. I needed to write a 1000-word “narrative event” piece for my writing course. My dad was in Berlin when the East Germans began constructing the Berlin Wall. I thought this would make a great topic, but the deadline was quickly approaching and I had yet to interview him.

“Dad, so remember I told you I want to write about your Berlin Wall experience for my writing class…remember?” I always hope he remembers. He told me a few years ago his plan to combat Alzheimer’s disease, should he develop it. He wants me to shoot him. “If you have to remind me of something more than ten times, just take me out,” he said. “Actually, make it eleven.”

He remembered. “Yeah, but to be quite honest, there ain’t a whole lot to it,” he said, breaking one of the two Schaber household rules- speaking with proper grammar. The other rule is no gum chewing in the house.

“I glad you remember,” I exhale. “Well, tell me what happened and then I’ll ask questions afterwards.”

He retold his experience during this monumental Cold War event in less than two minutes. It went something like this. In August 1968, my dad and a friend, Richard, were in Berlin staying with a host family: the Gastons. On a Sunday, Mr. Gaston told them the Brandenburg Gate had been closed. Fearing World War III, he told them they should leave West Berlin immediately. On the way to the train station, my dad and Richard stopped by the Brandenburg Gate to “witness history.” They saw a line of armed soldiers guarding the East Berlin border. They spoke with a few West Berliners. They continued to the train station and got on a train to West Germany.

I had my work cut out and a long list of questions. “What were you doing in Europe in the first place?”

“Oh man, I was on the greatest summer program ever.” My dad participated in a ten-week work-travel summer program organized by the University of Cincinnati. The program was divided into an initial three weeks of travel around Europe, followed by five weeks of work at an assigned location, capped by two final weeks of independent travel.

“First, it was the first time I ever rode on a plane and it was to cross the Atlantic!” He said. “It was a four-engine propeller plane. I was sitting next to where pilot would come out and look out the window to check how much oil was leaking from the engine,” he chuckled. “Oh, no. I didn’t dare tell Nonni that part.”

He spoke about meeting Richard during the first portion of the trip. “I remember we hit it off immediately, we both loved baseball and classical music. Actually…that’s right, he was a music major at Indiana University,” my dad remembered.

He spoke most enthusiastically when talking about his work assignment in Munich. For five weeks, he worked on a construction team that repaired buildings damaged during World War II. The team comprises guys around my dad’s age from Italy and Spain. Their common language was broken German.

“I had gotten Ds in all my German classes, but I was able to communicate quite effectively with them,” he said proudly.

He recalled how exciting it was using German to get to know new friends from a foreign country. This represented a watershed moment in his life. “I had barely left Ohio, and now I’m in Munich talking in German with the Italians!” He said. “All the Italians were communist and I remember one saying, “but we’re the good kind.””

This interview was going in the wrong direction. My impatience was increasing as my dad spoke about everything on the trip except the Berlin Wall. My teeth were clinched tightly and I stared wide-eyed at my list of unanswered questions. What did the West Berliners at the Brandenburg Gate say? Were you scared? How big was the crowd on the East Berlin side?

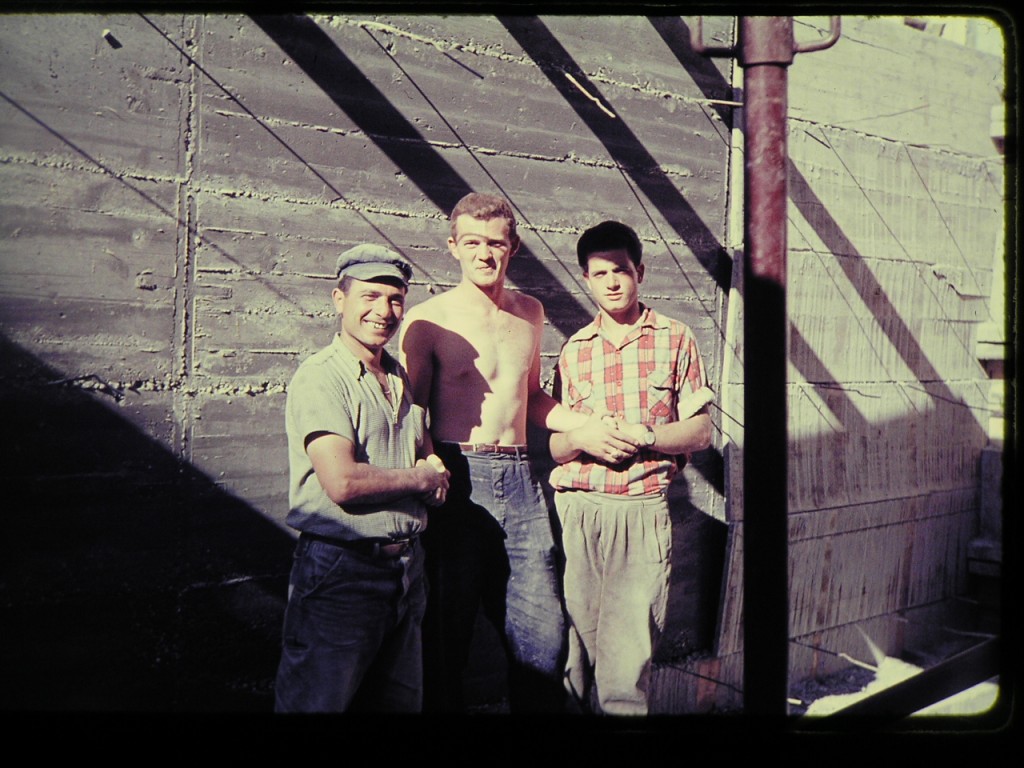

He remembered all of a sudden that he had pictures of the Gastons, his boss in Munich, and one of him with the Italians.

“Does your teacher want pictures included in the story?” He asked.

“I’m not sure, plus the story isn’t about…” I said, trying to contain my irritation.

“I’ll email them to you now, wait a second.” I heard my dad frantically clicking the mouse. His pictures crammed my inbox a few seconds later.

I attempted to bring the conversation back to the Berlin Wall. I asked what more did he recall from that Sunday morning, the day the border between East and West Berlin was closed. He recalled Saturday night instead.

“When Richard and I arrived, Mrs. Gaston told us she prepared a “traditional German meal” for us…It was roast beef, potatoes, and string beans.” I heard both my mom and dad laughing.

We finally returned to the Berlin Wall. He feared World War III would break out on that Sunday. There were no East Berliners on the other side of the armed soldiers…

My dad cut our conversation short. His racquetball lesson began in fifteen minutes.

“Okay, is there anything else you want to briefly mention?” I asked.

“It was such a great opportunity to travel; I have so many great memories from it- the flight, working with Italians in Munich, the Gastons, becoming friends with Richard…”

He didn’t mention the Berlin Wall.