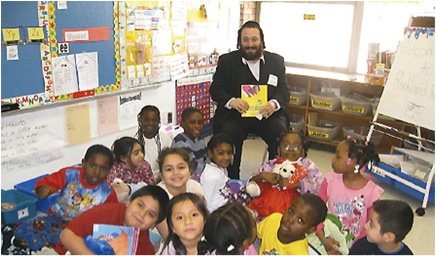

Aron Wieder, the Vice President of the board, keeps a Twitter account. His tweets vary from the cultural (“This purim—a springtime Jewish festival—it was unusually quiet on the streets of Monsey”) to the secular (“I read to the kids a Curious George book”). Photo: Aron Wieder.

BY SARIKA BANSAL

Steve Forman, one of Ramapo High School’s assistant principals, was stunned to find on a recent morning that his town’s sectarian feud had spilled into his school. On the blackboard in an empty classroom, someone had scribbled: “IT’S THE JEWS’ FAULT.”

Forman immediately knew the anonymous student was not referring to the latest conflict in the Middle East. The anti-Semitic jab was much less global. In all likelihood, the student was referring to the Jewish members of the local public school board, who have drawn fire over the dilapidated state of the school district.

The East Ramapo school district is deeply divided. Located twenty-five miles northwest of Manhattan, the suburb consists of a sizable ultra-Orthodox Jewish community, now the single largest ethnic group in town, and a mix of immigrant groups, including communities from Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Though Ramapo High School boasts a colorful mural with the phrase, “Unity in diversity,” the community has largely ignored this mantra. Over the years, festering tensions between the Orthodox and the non-Orthodox populations have led to disputes over real estate, traffic safety, and most contentiously, education. Non-Orthodox residents complain that the Orthodox community has used its political muscle to lower taxes and gut the public education system, while Orthodox residents contend that the district must be more responsive to the needs of the changing population.

These disputes mirror those in many other towns with bourgeoning Orthodox populations, such as in Long Island and in Brooklyn. East Ramapo’s tensions may be mounting to unprecedented levels, though, with the US Department of Education recently having begun an investigation to see whether the school board has engaged in discriminatory practices against public school students.

Ultimately, the community-wide dispute has the largest impact on the 8,200 students who attend the public schools, over half of whom are eligible for free and reduced lunch (a proxy for low-income status). The dispute also directly impacts the 17,000 children in East Ramapo who attend private schools, the vast majority of which are yeshivas, or traditional Jewish schools.

**

Long-time East Ramapo residents often talk about the “golden age” of the school district. “When I attended Ramapo [High School], it was a totally different place,” a middle-aged woman whispered to me during a school board meeting. “Things have really gone downhill.”

In the context of East Ramapo, the phrase “gone downhill” has several specific connotations. I grew up in the area and attended East Ramapo’s public schools, so I am familiar with several of them.

Among residents of Rockland County, which embraces East Ramapo, “gone downhill” most often implies the changing ethnic and socioeconomic makeup of the district. In 1989, 38 percent of Ramapo High School’s students were non-white; by 2009, this figure had jumped to 93 percent, due both to the influx of sizable immigrant populations and to “white flight,” defined in this case as hundreds of East Ramapo’s white families either moving or sending their children to other schools. “After white flight we began seeing black flight,” said Forman, an assistant principal at Ramapo High School. “Middle-class black families started to leave our district too. Who are we left with?”

“Gone downhill” also often refers to the perceived quality of education in East Ramapo. SchoolDigger, a national school-rating website, currently ranks Ramapo High School 824th out of New York’s 1113 public high schools. Less than 75 percent of students graduate, and of those that do, only 40 percent continue to four-year institutions. Most publicity the district receives today centers around fights, arrests, and gangs. This is a starkly different picture from twenty years ago, when East Ramapo was, according to my mother, a long-time resident, “considered one of the best school districts around, with some of the best teachers. That’s not the case anymore.”

More recently, “gone downhill” sometimes tacitly refers to the composition of the East Ramapo school board. The nine-person elected board has enormous influence on the school district: each member has a say in which lawyer the district should hire, which extracurricular programs to fund, and which union contracts to uphold.

The East Ramapo Central School District board in 2009. Five of nine members are Hasidic Jewish and send their children to private yeshivas. Photo credit: Vos iz Neias

Historically, the board consisted of ardent parents of East Ramapo students. Over time, however, the town began electing several equally ardent “private school parents”—a local euphemism for Orthodox residents—to the board. Members of the grassroots group East Ramapo Stakeholders for Public Education, among others, have credited the elections to a supposed Jewish bloc vote combined with general voter apathy. They have also complained that many of today’s East Ramapo parents are not US citizens and thus have no say in local elections.

As of April 2011, there were five Orthodox or Hasidic Jewish men serving on the nine-member public school board. All of them send their children to private schools. These board members included Nathan Rothschild, who served as President of the school board from 1998 until his sudden resignation on April 14. The following day, he appeared in a US District Court on unrelated felony charges (he is accused of engaging in mail fraud while serving as fire commissioner in Monsey, one of East Ramapo’s more Orthodox neighborhoods).

**

The majority of Orthodox Jews in East Ramapo identify as Hasidic, meaning they follow the teachings of 18th century Rabbi Baal Shem Tov. Hasidim, a subset of Orthodox Judaism, is often considered “ultra-Orthodox” due to its strict creed and emphasis on tradition. Children must attend religious yeshivas, where they study traditional Jewish texts; women must dress conservatively, covering their knees, elbows, and after marriage, heads; and men must wear payot, or sidecurls, starting at age three. Many Hasidim today live in self-segregated communities.

The Orthodox and Hasidic Jewish members of the East Ramapo school board are no exception. Most of them live in or near Monsey, which is reputed to be one of the most densely populated Hasidic Jewish neighborhoods in the United States. As of 2000, it had at least one synagogue for every 150 residents.

Three miles north, the Village of New Square is East Ramapo’s most homogenously Hasidic neighborhood: according to the Modern Language Association, over 90 percent of the area’s estimated 8,000 residents speak either Yiddish or Hebrew at home. Rockland Magazine in 2007 called it “a densely packed haven where Hasidic residents live largely by their own customs and laws.”

It is difficult to determine the exact size of the Orthodox community, since the census does not record religious affiliation. Growing up in the area, however, I witnessed East Ramapo’s transformation as the Jewish community grew to be the town’s largest ethnic group. The local supermarket, Grand Union, morphed into Wesley Kosher when I was in fifth grade. Two years later, empty plots down my street began to be developed into single-family homes. When my sister and I snuck around the half-completed construction sites, we were surprised to find that they all had two kitchens—one for meat and the other for dairy, in accordance with kosher food rules. By the time I got my driver’s license, my parents warned me to drive extra carefully on Friday evenings, since Hasidim walking back from synagogue sometimes forget to wear reflectors over their long black coats.

**

Among East Ramapo’s Hasidic school board members, Aron Wieder is the most vocal, the self-proclaimed “lightning rod” of the group. He is also the most visibly connected to East Ramapo’s secular community, largely due to his day job as administrative assistant to Noramie Jasmin, the Haitian-American mayor of the nearby village of Spring Valley.

Wieder has drawn polarized opinions from East Ramapo residents. His supporters—mostly (though not exclusively) members of his community—applaud his sharp mind and charisma, while his critics, including Steve White of the East Ramapo Stakeholders, denounce him as a baby-kissing politician bent on lowering property taxes at the expense of public education in East Ramapo.

White lost to Wieder in the 2008 school board election by 300 votes, but says his animus isn’t personal. “I think he is not an honest person,” White said. “He’s a politician who’s got a handler somewhere.” White also said the Hasidic community, many of them landlords in East Ramapo, has no interest in maintaining the public education system being used primarily by their tenants, or the “immigrant worker class.”

Wieder avoids calling his critics anti-Semitic, but acknowledges the role of prejudice in shaping opinion. “They say that I’m a private school parent, and that I have no right to be on the board,” Wieder said to me in his windowless office in the Spring Valley Village Hall. “Many are very accusatory. The truth is that I’m a very strong believer in public education.”

To back his claim, Wieder recounted a story he said he shares with many East Ramapo parents. “About three-o-clock in the morning, my wife ended up in the emergency room, giving birth to my youngest child. She had a very good experience, thanks to a wonderful nurse. Very professional. I got to have a conversation with that nurse, and it turns out that she was educated in East Ramapo.

“Who are my co-workers? Not people from my community. I interact with a bank teller, who happens to be a graduate of East Ramapo…. Regardless of where I send my kids to school, I have a vested interest in public education. That’s why I feel privileged to be on the board, to perhaps make a difference in the district.”

White, meanwhile, claims the biggest difference Wieder has made is to successfully reallocate resources from the district to the Orthodox community. “When Wieder was elected, he had a single-minded focus on changing special education,” said White, who is half-Jewish. White described how Wieder worked tirelessly to find loopholes that would allow the school district to fund yeshiva tuition for Orthodox children with special needs—even when adequate special education services existed within the district.

Many of White’s frustrations stemmed from a controversial 2009 board decision—taken at 1am—to replace the district’s long-standing lawyer with a costly Long Island attorney, Albert D’Agostino. According to New York Times coverage of the incident, D’Agostino, who had represented Orthodox-controlled school boards in the past, had been “enterprising in finding lawful ways to provide special education services at shared expense to private school students.” At the time, he was also under investigation by New York’s attorney general.

Wieder defended his actions. He said the district was treating these parents poorly, and that he was helping East Ramapo taxpayers get the services to which they were entitled by law. He also said the previous lawyer was “ineffective.”

Wieder speaks with his hands, and as he gets deeper into an argument, his Brooklyn accent becomes more noticeable and his payot begin swaying gently. Like an experienced politician, Wieder’s gaze remained fixed on my face throughout the interview, and unlike most conservative Hasidim who avoid physical contact with the opposite sex, he shook my hand warmly when we parted.

**

At school board meetings, Wieder’s body language is remarkably consistent. During a community session in March 2011, in which various residents spoke against impending budget cuts, Wieder listened attentively to all.

“Music education has been proven to improve test scores. We can’t take that away from our children,” begged a red-faced mother between tears. “Let our children come to clean buildings they can be proud of,” pleaded a custodial staff member, in response to threats to cut staff. A retired teacher, in the face of possible cuts in security, said, “Everyone heard about how four Ramapo students were arrested yesterday [for fighting]. East Ramapo’s children need to come to safe schools.”

Throughout these impassioned speeches, Wieder leaned his body forward and furrowed his brow. He made direct eye contact with speakers whenever possible. He was listening.

Wieder listened with equal interest to Kalmen Weber, the Hasidic president of the Southeast Ramapo Taxpayers Association. Unlike previous speakers, Weber fervently defended the impending budget cuts. He repeatedly told the board how East Ramapo was facing “times of sacrifice,” and how during such times, the public schools should feel the pinch as much as the taxpayer. Parents in the audience began booing during Weber’s speech, but Weber and Wieder ignored the interjections.

Immediately after the session, Wieder approached several speakers individually and thanked them for their comments. “I understand your concern with the school district’s attorney fees,” he told a PTA member who had complained that the budget was being allocated poorly. “Many parents have raised similar concerns.”

When it was finally his turn to address the group, however, Wieder took a hard line, endorsing the proposed budget cuts. Taxes are high, he said apologetically, and most of the proposed cuts would not directly affect student graduation rates. “We must be cost effective,” he told audience members, many of whom were shaking their heads and whispering angrily to each other.

**

Tensions in East Ramapo have been mounting even higher lately with changes in leadership. The board recently demoted the district’s superintendent, Dr. Ira Oustacher, to interim director of special student services, for reasons unclear. In a public statement, Rothschild just said, “I think the board wanted to see a little different direction.”

Two weeks later, on April 14, Rothschild resigned from his position as president of the school board, the day before he appeared in US District Court. He has been accused of settling a personal debt by selling land owned by the Monsey Fire Department to his unnamed creditor, at below market rate.

Four days later, Aron Wieder announced that he would not seek re-election for the board—despite his tweet on April 3 that stated, “Tomorrow I’ll be announcing my re-election bid as an East Ramapo Trustee. It will be a low key announcement via email to supporters :).”

Speculations abound. Some, including activist Peter Obe, wonder whether Wieder wants to maintain a low profile during Rothschild’s investigation for fear of being implicated. Others, such as activist Joe Dais, believe it was a deliberate tactic to lay groundwork for a new slate of Orthodox school board candidates. “They’re always four, five moves ahead of the rest of us,” he said.

In the last month, the school district has attracted federal scrutiny. The Spring Valley chapter of the NAACP announced that the US Department of Education is investigating whether East Ramapo has been mismanaging resources and shortchanging minority students in the process. The content and scope of their investigation is confidential, but many residents hope federal officials will play a constructive role in the ongoing debate.

Across the district, people appear frustrated with recent events. “There’s no transparency anymore,” complained a Spanish teacher in the teacher’s lounge at Ramapo High School. “All I know is there are some funny politics going on.”

Things should begin to change on May 17, the date of the school board election. Four of the nine seats are up for grabs. The East Ramapo Stakeholders are officially promoting four public school parents. Running against them are four Orthodox candidates, including two who are vying for Rothschild’s position.

Despite there being 49,000 registered voters in East Ramapo, if historic voter trends continue, the winners will be decided by a few hundred votes.

1 comment for “Sectarian War in East Ramapo Schools”