BY S’HA SIDDIQI

My grandparents’ story isn’t particularly novel.

It is the shared experience of millions of Pakistanis and Indians who have yet to come to terms with the full extent of injury – both physical and emotional – that the Partition has left. It’s permeated the culture and history of the subcontinent as each subsequent generation passes down their doubts and mistrust to their children.

Their fears have become our collective legacy.

As someone who was born in Pakistan and moved abroad at a young age, I have always been fascinated by the relationship between the two countries. It became a central theme in both my academic and professional life. That interest redoubled following increased hostilities on the border after a suicide bombing in Kashmir this past February. I began researching the crisis – talking to politicians, soldiers, and civilians from both sides of the conflict in a hope to better understand the tensions between Pakistan and India.

When I mentioned this project to my family recently, I was surprised when my father suggested I should start my research by talking to someone I already knew.

After a brief conversation, he suggested speaking with his parents to hear their experiences with India and perhaps better understand why the rivalry between the two nations is so endemic to our shared national consciousness over seventy years after independence.

That’s how I found myself sitting in my apartment in New York, staying up late to take advantage of the time difference and catch them after they ate their breakfast. I had seen them earlier that year when I had flown to Islamabad, but my phone calls with them were usually contained to holidays and birthdays. So naturally, they were surprised by the nature of my call.

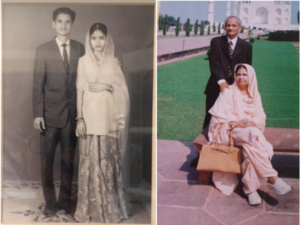

I’m a bit embarrassed to say, that though they have always been loving and often ask after my own accomplishments, I didn’t actually know much at all about their lives. My grandfather, Ainuddin Siddiqi, is an eighty-four-year-old retired federal secretary. My grandmother, Swaleha, is a seventy-seven-year-old former Urdu Professor. However, before this call, there was little else I could tell you about their pasts.

The conversation that followed changed all of that.

Partition

At midnight on August 15th, 1947, the newly formed states of Pakistan and India legally gained independence from British Rule following the end of the Second World War.

It was midnight, and my grandmother had just turned five years old.

At the time, she and her family, lived just outside the Himalayan mountain city of Shimla, India. The city is infamous for the kaleidoscope of colours homes dotting the slopes and for the heavy snowfall of its winters. Her father had been posted there as a part of the military, and the word Partition sat heavily on the tongues of his unit. Following independence, the soldiers had been given a choice – to remain in India or to join Pakistan’s military forces.

Her father chose Pakistan, and soon she found herself on the move with her parents and two younger siblings. They walked down the steep hills, occasionally hitching a ride in a cart, the back of a truck, or in a train compartment. They took almost nothing with them, just a smattering of personal possessions that they could carry. Over the next few days they moved quickly, swiftly – intent to reach to seaport of modern-day Mumbai.

In the early months of Partition, travel was dangerous and rumours of ambushed massacres were rampant, punctuated by a growing body count left abandoned on the side of the road. Tensions between the Sikh, Hindu, and Muslim populations were high, and it was common to pass by entire villages stinking of carnage and blood-soaked dirt. Many travelers had taken to carrying canteens filled with rain water because the wells along the way held the bodies of women and children who chose to drown rather than face rape and violence at the hands of vengeful mobs.

My grandmother and her family were lucky enough to avoid any of these roving groups of vigilantes. They traveled with other military officers and had the benefit of scouts who ran ahead of their group.

“It was very dangerous. If the way wasn’t clear they would double back, find a new route,” said my grandmother. “So many other people died, but what do you do? Some didn’t have a chance to get through.”

They wove their way carefully, sticking with the army until they were delivered safely to the coast. There were several ships at port, thousands of people waiting to board but they were able to bypass the lines – taking refuge on a military vessel. My grandmother doesn’t remember the make of the ship, but she does remember the journey.

Officers were provided rooms below deck for their families, like her father, and those lower in the chain of command simply huddled out on the decks. My grandmother, who had never seen the ocean before, spent most of her time above deck hanging over the railings and staying near her mother who chatted with the other army wives.

“It was an adventure, I kept looking through all the windows,” she said as she laughed over the phone. It was a sharp contrast from the anxious journey over land and they made it easily to Karachi’s port in Pakistan within a week.

My grandfather interrupted at point, some muffled agreement coming over the speaker before his voice came through clearly. He too, had taken a ship from Mumbai, though his journey had been somewhat different.

During Partition, my grandfather had been twelve years old and lived in a small town outside of Aligarh, India which was in the center-north of the country. Aligarh is renowned for their university, though he had been too young to attend at the time. The rumours of ethnic riots had reached him as well, and unlike my grandmother, he did not have the advantage of traveling with the military.

His family decided to test the waters, and they made the journey in separate waves. My grandfather is one of nine children, and one of the oldest, so his parents risked sending him ahead with two of his sisters. Abida was only nine at the time, and they were both under the watchful eye of their eldest sister Khadija and her husband – their two toddlers in tow. They made the entirety of the eight-hundred-mile journey by train, managing to avoid the worst of the slaughter further east by going south instead. Most of the ambushes occurred for those attempting to make the border crossing by land, but they hoped to go by sea instead.

When they arrived in Mumbai, they weren’t able to travel again immediately. The city had set up some temporary camps for those who had been displaced and his party had found themselves huddled there for three days. They had almost nothing with them, little food or coin. It was obvious that they would have to something soon before their meager funds ran out altogether.

Eventually, his brother-in-law, Naseem, decided for them. He used what he had left to purchase a ticket on one of the commercial vessels that was intended to leave that same day. He tugged them along, his young wife and four children behind him. People were tripping over themselves to get onto the ship, desperate not to be left behind and to be stranded. By the time my grandfather reached the docks, the ship was about to depart. Naseem shoved his way through and got to attendant presenting his ticket.

“The ship was leaving, and [Naseem] tried to convince them to let the rest of us go through too,” my grandfather told me. The attendant had waved them off but it was his older sister who stood up, spine straight despite her haggard appearance – two babies in her arms. “She refused to leave. She pushed through until he stepped aside.”

His family climbed up the gangplank, making their way safely onboard and on their way to Karachi.

My grandfather mused it might have been because of the time, that the attendant wasn’t willing to turn away one last mother on the docks as the anchor was being dragged up. One last exception when the rest of the line had already been turned away.

He doesn’t know what they would have done if they had been refused. They had no more resources. No money for a train. If they were going to cross, they would have had to make the thousand-mile journey by foot.

It was a death sentence.

The Indian Partition led to the largest mass migration in recorded history, with UN estimates putting the number at nearly fifteen-million in 1947 and led to the deaths of another one-million. Most of those occurred in the province of Punjab that dominates both sides of the Pakistan-India border.

The aftermath of both my grandparents’ migrations further cemented this fact.

After arriving in Karachi, my grandfather’s family found themselves seeking shelter in a small home in the district of Harama. It was little more than a one room hovel, that they shared with others. They slept where they could, in the kitchen or outside. Most importantly, however, they didn’t have to purchase or rent it – it had been abandoned by a Hindu family fleeing west to India.

The city was filled with houses with similar stories, not unlike the homes my grandparents had abandoned when they had left India themselves.

After arriving in Pakistan, my grandmother’s father had been posted in Lahore, a city right near the border and it was easier to keep track of news between the states. It was also the locations of one of the few train lines that ran between the two countries.

She recounted how Lahore taught her exactly how lucky she had been to have taken passage on a ship rather than a train.

“The trains would come in and they would be filled with bodies. Whole trains butchered when they arrived at the station, “my grandmother said, pausing for a moment to ask if I had met her sister Akhtar before. I wasn’t sure, though I recognized her name from my father.

She continued to tell me that her sister had made the trip using the railway, hoping to join them in Lahore. The train she arrived in was a verifiable coffin, spilling with corpses when the doors were opened. Aunt Akhtar and her husband had hidden beneath the bodies, lying flat and covered in the blood of strangers to escape notice.

They were part of the small fraction of survivors who managed to hobble out of the compartments.

The Indo-Pak Wars of 1965 and 1971

Eighteen years later, after decades of cautious peace, India and Pakistan broke into their first war. By then, my grandparents had married and were living in Lahore where my grandfather worked as an officer for the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission. They had one daughter and lived by the army outpost in the city.

Their recollections of the fighting, which lasted just over a month, were stark.

Pakistan troops had moved past the line of control in Kashmir, where the borders were still highly contentious in order to advance their territory. Unsurprisingly to me, my patriotic grandparents supported the military action. The borders had never been settled in Kashmir, and it was a festering wound from the chaos of the Partition. The border become a hotbed of military action, and the city of Lahore was soon under fire. The night blared with sirens, the rocky drone of fighter planes ringing clearly as the bombing began.

Tanks crossed the border, and my grandmother recalls how the citizens of the city rallied in defense. They tried to block the advance, some strapping bombs to their chests and standing in front of the approaching vehicles. If they didn’t stop, they detonated – keeping Lahore out of Indian hands. It was overwhelming, and like so many other families, they decided to split up. While my grandfather needed to remain, he sent my grandmother and their young daughter back down to Larkana to stay with family.

“She was scared, and she would cry when the sirens went off,” my grandmother told me. It made sense to leave. Tucked out of the way, Larkana was not a military target, and instead she simply watched the news carefully for progress until a ceasefire was signed. It put them both on edge and left little love-loss for India.

She had only been twenty-two at the time, while my grandfather was thirty.

Their opinion of India did not improve after the war ended however, as hostilities boiled over once again in 1971.

In 1971, East Pakistan fought for independence with the help of Indian forces and became modern day Bangladesh. To my grandparents it was a mortal wound, and one that was not easily forgiven. “They broke one of our arms,” my grandmother said, though it took me a moment to realize she didn’t mean it literally.

The war for Bangladeshi Independence led to over 300,000 Bengali casualties by independent estimates, with the official Bangladeshi numbers reaching to 3 million. Though contentious at the time, most modern historians also consider it to be a site of genocide after a violent crackdown by the West Pakistani army to quell political opposition.

Despite the Pakistani government’s reluctance to recognize the genocide, my grandparents don’t deny any of it. They consider it to be a national tragedy – a disgrace. East Pakistan had never been treated equally, even before the civil war. It had always been given less attention, less resources.

The slaughter that followed is not something that they could excuse.

“It was so much worse than [the 1965 war], we were just tearing ourselves apart,” my grandmother said. “We were killing each other.”

And yet, for her – India had made it worse. It had fanned the flames and armed the rebels, making the conflict bloodier than it had to be. For her, India’s intervention was not an act of humanitarian relief but a political maneuver to rip Pakistan apart.

I don’t claim to understand India’s motivations, national rivalries are never simple. However, I do understand my grandparents.

To them, the 1971 Civil War only served to conjure the specter of Partition.

Memories of the Partition are painful in the subcontinent, partially because fighting broke out on how the lines for the new countries were drawn. The disputed nature of Kashmir is a stark reminder of those original territorial arguments, and 1971 only managed to further aggravate tensions as Pakistan was divided in half permanently.

At the time of the war, my grandparents lived in Karachi with their three children. However, the war brings two recollections forward for them. For my grandfather it was traveling on official business to Dhaka, East Pakistan for the Atomic Energy Commission in the days before the city fell to the liberation front.

Bangladeshi liberation forces swept through the city of Dhakka; protests were in full swing as they overtook the government buildings and the Awami League became the defacto leaders of East Pakistan.

My grandfather had been boarding a plane back to Karachi that day. It had been one of the last flights out of East Pakistan before the airports closed. He hadn’t realized war had broken out until after he landed.

“The remaining [Pakistani] politicians in Dhaka were immediately arrested or killed,” he told me.

A few hours had made all the difference.

I could hear my grandmother humming in agreement in the background before she took the phone back from him. It appeared that though she lived in a different city, they were still in the line of fire as Karachi found itself under bombardment. The sirens began blaring again, the flights flashing as the city was under attack.

“This time you could see the fires from the window,” my grandmother said. The fear was more potent since she didn’t leave the city as she had in Lahore.

Kargil Crisis and Beyond

The last major conflict between the two countries occurred in 1999, and Kashmir was once again at the heart of the issue. In the war, Pakistan had taken hold of Kargil, a strategically important district high in the mountains. However, my grandparents’ opinion of the conflict was not what I was expecting.

“They did wrong by them, they were starving and they were freezing. They were trapped,” my grandmother said, voice weary.

I asked her if she meant the Indian troops.

She clarified, blaming the Pakistani army for sending their men into what was a doomed situation. She called Pakistan’s decision a waste. Unnecessary. The fighting never bled out past Kashmir to the heartland of either nation and it was quickly subdued, the world rattling at the thought of two newly nuclear states engaging in further warfare.

This last conversation about the Kashmir conflict, that had captured my initial attention, was fairly subdued. Though it was no less important, I was struck by how easily she dismissed it.

Of all the stories I heard from my grandparents, Kargil is the only one I was old enough to recall well myself. To me, it’s the modern narrative and the history I’ve known. I remember the Kargil conflict from when I was younger, about the debates over territorial lines, of possible independence, and the lingering dangers of nuclear potential.

However, through my conversations with my grandparents, it was clear that their wounds were much older.

They had been gathering scars since they were children, a legacy of malcontent and horror between the two countries.

Yet, despite everything they told me thus far, it was not a story of war that struck me the hardest, but a trip they had both taken in 2008 to visit India.

They had gone to Aligarh, where my grandfather was from, for a reunion.

They had spent time in the country of their childhood visiting various tourist sites and seeing family they had long lost contact with. While there, my grandfather met a cousin of his and asked her to show him his old home. She told him it had been taken over by a Hindu family after they had left it, just as he had taken refuge in the abandoned Hindu home in Karachi as a child.

She was initially hesitant, but he insisted and she eventually agreed.

The streets weren’t quite the same. There was new construction and many old store fronts were plastered by posters of the latest Bollywood films. There were now powerlines and TV satellites visible from the rooftops, and pedestrians and motorcyclists crowded the road below.

It was a far cry from his memories from 1947.

Still, my grandfather was still hit by the nostalgia of it as he glanced up at the building, taking in the familiar windows though the curtains framing them were new. The front door was new too.

He knocked.

A man came to the entrance and my grandfather explained who he was and asked if it was possible to take a look inside, to see it one more time.

“I wondered what else had changed. Would the rooms feel the same?” My grandfather said. “I was so young when I left but this was still my father’s house.”

“This was my home,” he told me.

He explained it all to the man at the door, but in the end it didn’t make a difference.

“He said no,” My grandfather sighed. “This was my home, but he said no.”

The man’s answer stayed with me, and a couple of weeks after my conversation with my grandparents, I found myself wondering what my grandfather would have done if their situations had been reversed.

Eager to find out, I called him.

I posed my question and asked if my grandfather would have allowed an Indian man to come into his house in Pakistan, if he claimed it to be his ancestral home.

It was silent on the line for a moment as he considered it.

“Yes,” he replied. “I would have.”

My grandmother took longer to respond, though her answer was perhaps more telling.

“I don’t know,” she said.