BY LUCIA ZERNER

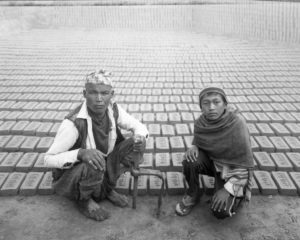

Courtesy of Kevin Bubriski

A Newar father and son kneel in front of their life’s work, a sea of clay bricks drying in the cool Kathmandu Valley air. From the photo, it’s as if their gaze looks directly at us. The photo was taken in 1987 by a young American whose life was changed by encountering Nepal. His images in turn have shaped the way Nepalis and the wider world see the country and its history.

That documentary photographer, Kevin Bubriski, is an American who began his career in the late 1970s making pictures of remote Northwest Nepal. Since then, he has travelled throughout Asia and the Middle East capturing scenes of daily life.

I grew up with his photographs, one hanging on a wall and others in books my parents had collected. Though I had seen Nepal through his photographs, it was years later that I travelled to Nepal as a Fulbright fellow along with Bubriski. I called Bubriski in mid-October to learn more about his story as a photographer. He spoke to me by phone from his home in Vermont.

A Rasta artist Bubriski met years ago in Belize said it best: “You’re taking pictures now to show the future what the past looked like,” recalled Bubriski. “He said it so simply, so perfectly, and that’s what I do.”

This particular eye for the value of the photograph over time has created archives that might otherwise have not existed. His images not only convey what the world looked like but also inform the way the world is now and what it might look like in the future.

His journey as a photographer began following his time as a twenty-year-old Peace Corps volunteer in the mid-1970s. While living in villages installing drinking water pipelines, “I witnessed people dying of hunger, lack of any kind of medical attention,” he said.

A few years later he returned to the Nepali Northwest. “I felt I had a story to tell about what I had experienced as a Peace Corps volunteer living in communities where peoples’ lives were at risk everyday,” he said. Carrying a large view camera across the rugged terrain, Bubriski photographed men, women, and children.

“I saw value in it,” Bubriski recalled. “Out in the village, people would say, ‘Why are you taking my picture?’ and I’d say, ‘You’re going through development, things are changing’.”

Now in his sixties, living in Vermont, Bubriski recalled, “When I went to Nepal I was everybody’s little brother, bhai, and now when I go I’m grandfather, bhaje. So, I’ve changed from being a young man to being an old man and Nepal has changed, with the proliferation of roads, the explosion of population, the use of resources, the migration to the cities.” He has travelled to Nepal fourteen times. His book, Nepal: 1975-2011, portrays his views of Nepal over four decades by bringing images of the old and new in conversation with each other.

Change is a theme that Bubriski grapples with in all of his work. In 2016, he travelled to Mustang, another remote region in the mountains of Nepal. The resulting book, Mustang in Black and White, examines the confluence of the old and new, from “beautiful old monasteries and pilgrim caves” to “motorcycles and land cruisers.”

Throughout his career, Bubriski has tried to look at what remains of the past, what exists in the present, and how those two converge to create and shape what will be.

This effort continues, closer to home, with his current project. His new book, Our Voices Our Streets: American Protests 2001-2011, documents anti-war and Occupy Wall Street protests in cities and towns across the U.S. Like his archive of photographs of Nepal, these images “look back and re-contextualize history, where we’ve been and who we are.”

Bubriski views it as his duty to photograph what is unfolding around him. “How can I be a photographer and not pay attention to what’s going on three hours drive from where I live?”