Russian Exiles Who Crossed Lines to Aid Ukraine

Roman (right) flew with 26 duffel bags of aid for Ukrainian troops

By Mariel Povolny

The Organizer

It was February 27, 2022— three days after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The Organizer and his friend drove a van loaded with children’s camping gear from a neighbouring Eastern European country into the mountains of Western Ukraine. As political talking heads declared that Kyiv would fall in days, the Organizer, an older Russian businessman living in exile, knew he couldn’t stand by. Despite the considerable risks for a Russian citizen helping those whom the Kremlin considers enemies of the state, he felt compelled to act.

That night, he started packing his things to join the Ukrainian fighters. “Then my wife came in, she said, ‘Who the hell is going to raise our son?’”

He decided instead to deliver supplies to Ukrainian troops. Travelling with Russian passports, he and his companion needed an escort from the Ukrainian military to cross into Ukraine. When they arrived, their contact wasn’t there yet. Soldiers examined their passports.

“When those soldiers on the border saw our Russian passports, I really thought they’d shoot us on the spot,” he said.

The Organizer grew up in Russia, building several successful businesses before mob violence forced him out. He moved to a new country in Eastern Europe and started a successful hospitality business there. Though he lives abroad, the Organizer is incredibly cautious about revealing details of his mission and asked to remain anonymous for this piece. In Russia, even minor expressions of anti-war sentiment can result in imprisonment. His concern extends to loved ones still living under the Kremlin’s reach.

He never considered asking others to make the trips in his place. “Who would I ask to take that kind of risk? I’m not some general who can send people to their deaths,” he said.

That February 27th trip was the first of seven the Organizer would make to Ukraine. The effort began with camping supplies he’d accumulated over decades of leading mountaineering trips in Eastern Europe. He then reached out to friends in the United States who fundraised and delivered supplies to him: boots, helmets, bulletproof vests, and hemostatic control tourniquets.

“We brought anything that we could get our hands on. Everything except weapons,” he said.

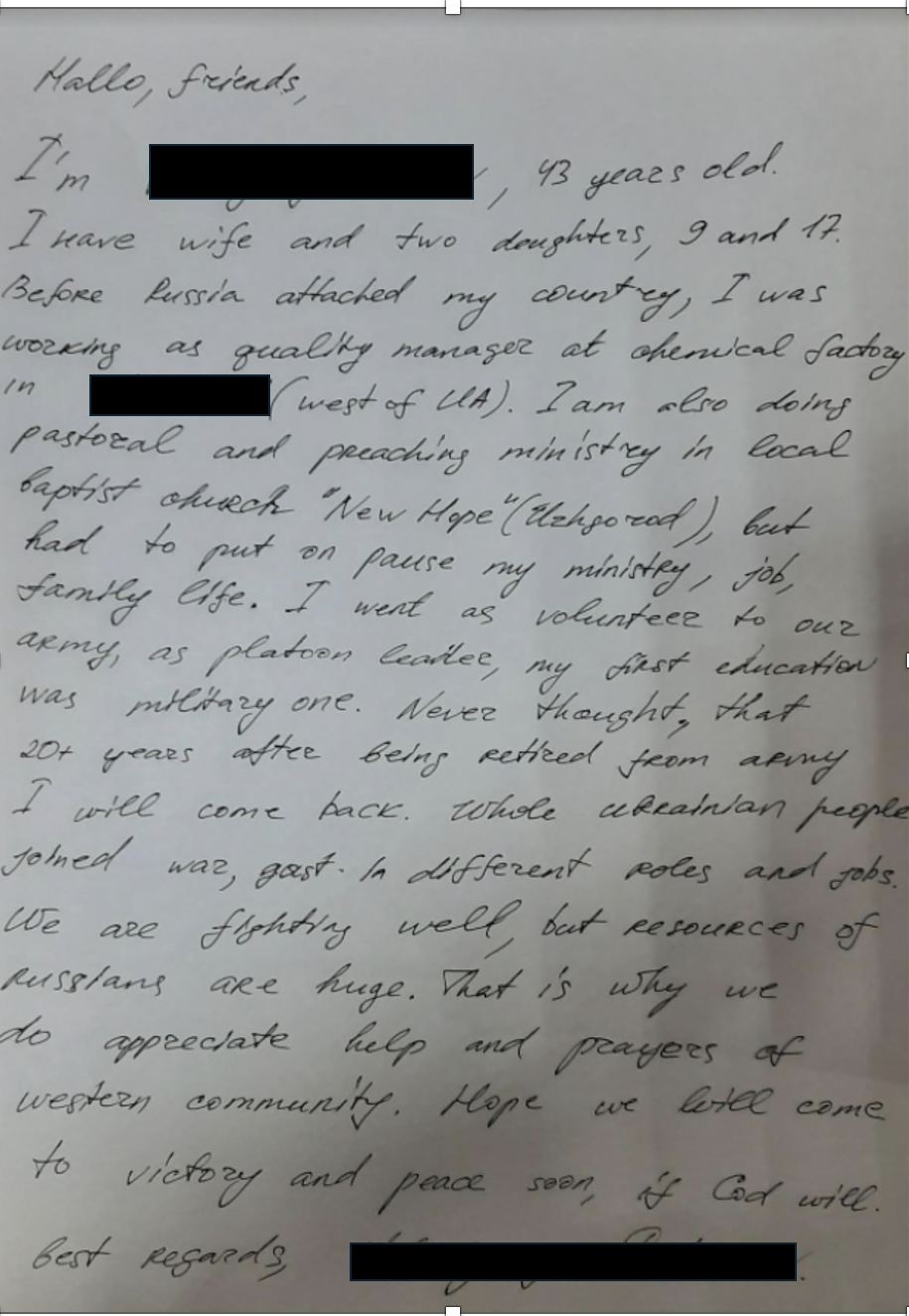

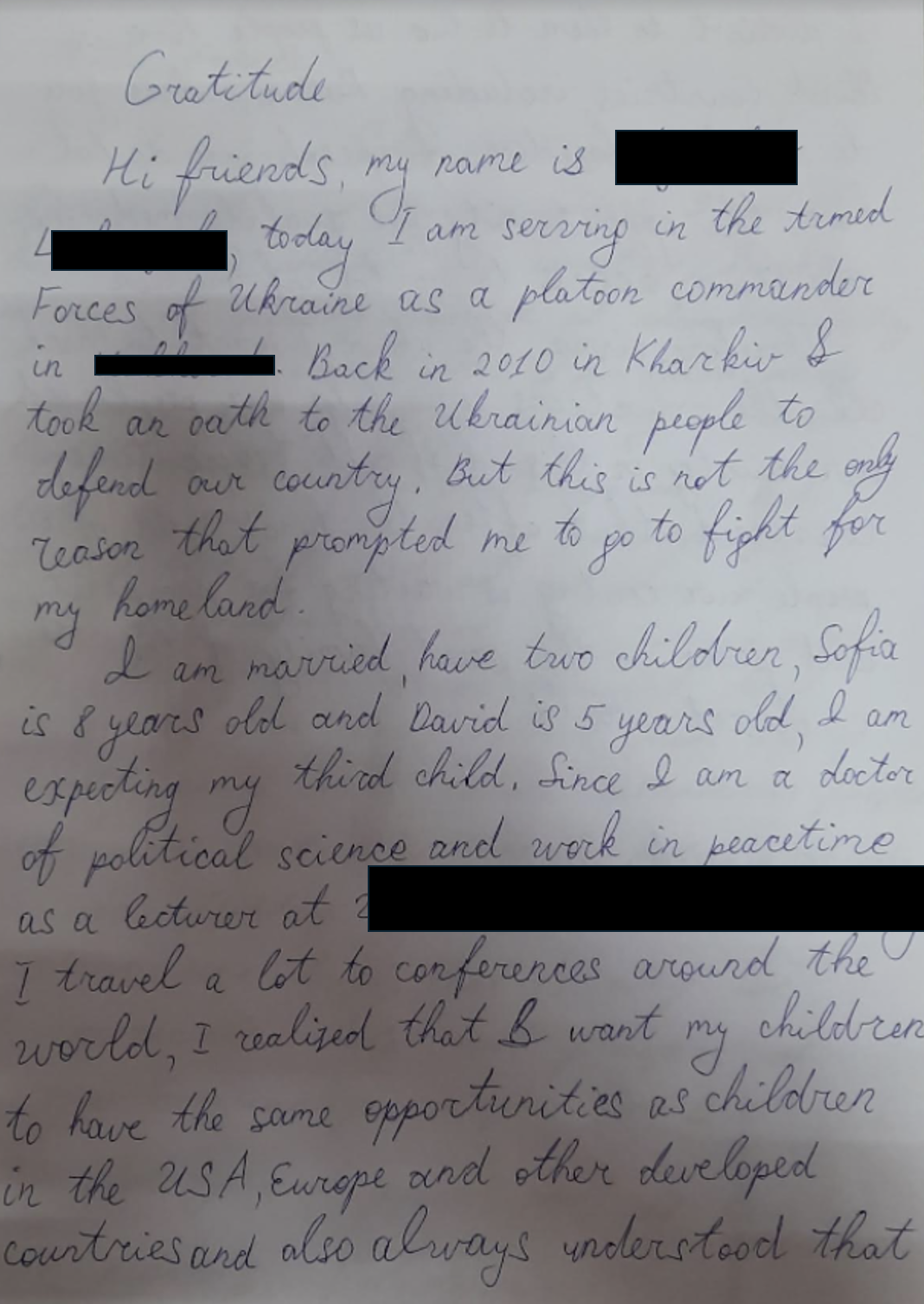

The supplies went directly to Ukrainian troops. Some wrote letters, thanking the Organizer and other volunteers for their support. Many of these men have now been killed in the fighting.

Thank you letters from Ukrainian troops

It wasn’t just Americans or Russians living in the U.S. who supported his efforts. “Some of my friends in Moscow sent very large amounts of money for me to use to buy supplies,” he said. “It was very risky for them, and it’s still dangerous. They could go to prison for 20 years.”

The Organizer’s trips continued until his Ukrainian contacts assured him that they were receiving sufficient aid from other sources. Though he’s no longer making these direct trips, his commitment to Ukrainians hasn’t wavered. He now hosts refugee families in one of his hotels. “Every family has their own tragedy. They’ve become resigned. They’ve lost any hope of resisting.”

“I feel sorry for the thousands of Ukrainians dying, and for the thousands of Russians dying too,” he said. “Those Russian kids could also be my kids.”

The Courier

A key member of this effort, Roman, had the option to remain anonymous for this story. “I’m already a traitor to my country, you can use my name,” he said.

Roman left Russia 30 years ago along with his partner, his seven-year-old daughter, and his ex-wife. “Part of it was professional, but I don’t think that was most of it. Living as a gay man and having to hide, that was hard,” he said.

Roman didn’t consider himself a political person for most of his life. “I started to feel like that only in 2014 when he [Putin] annexed Crimea. I knew it was the precursor to something bigger,” he said.

He started posting on social media then. In the years since he’s lost his relationship with almost everyone he still knows in Russia.

“I’ve had to block most of them on Facebook. We can’t discuss things,” he said.

He remembers the morning of February 24, 2022, when he turned on his TV and saw that Russian troops were invading Ukraine. “I was in my kitchen. I opened a bottle of vodka, had a few shots. I couldn’t believe it—I thought Putin just wanted to provoke, to scare them,” he said.

A friend called him a few days later. She knew someone delivering aid directly to Ukrainian fighters — the Organizer. He needed supplies flown from the United States.

Roman was on board. “I was happy to help. Governments are slow, aid is slow; nothing was getting in,” he said. He travelled in late March 2022 with 26 duffel bags full of socks, boots, and winter clothes. He carried two bags of headlamps onto the plane.

He didn’t worry much about repercussions for himself or his parents, who still lived in Russia. “Some official called my parents at one point asking where I was. I’m still registered at their address. I think they also sent some papers asking for me,” he said.

Earlier this fall, Roman went to Ukraine to visit his cousins. He flew to Moldova and took a bus five hours to Odessa. The trip was only possible because he holds an American passport.

“At first, it seems like there are no changes. The buses run, people go to work. Then you hear the sirens,” he said. “My family, they’re so used to it they don’t go anywhere to hide.”

Roman believes the West has repeatedly enabled Putin by failing to take a firm stand against his aggression. He likened it to the Allied powers’ appeasement of Hitler during the Munich Agreement, which effectively sanctioned the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. “They thought if they gave him what he wanted, he would stop,” he said.

“This war will end in negotiations. Ukraine will lose territory. It won’t stop Putin—he will attack again. But if the Ukrainians are smart, they will be ready,” he said.