How a missile attack on a train station came to emphasize the role of investigators tasked with combating disinformation about war crimes in Ukraine.

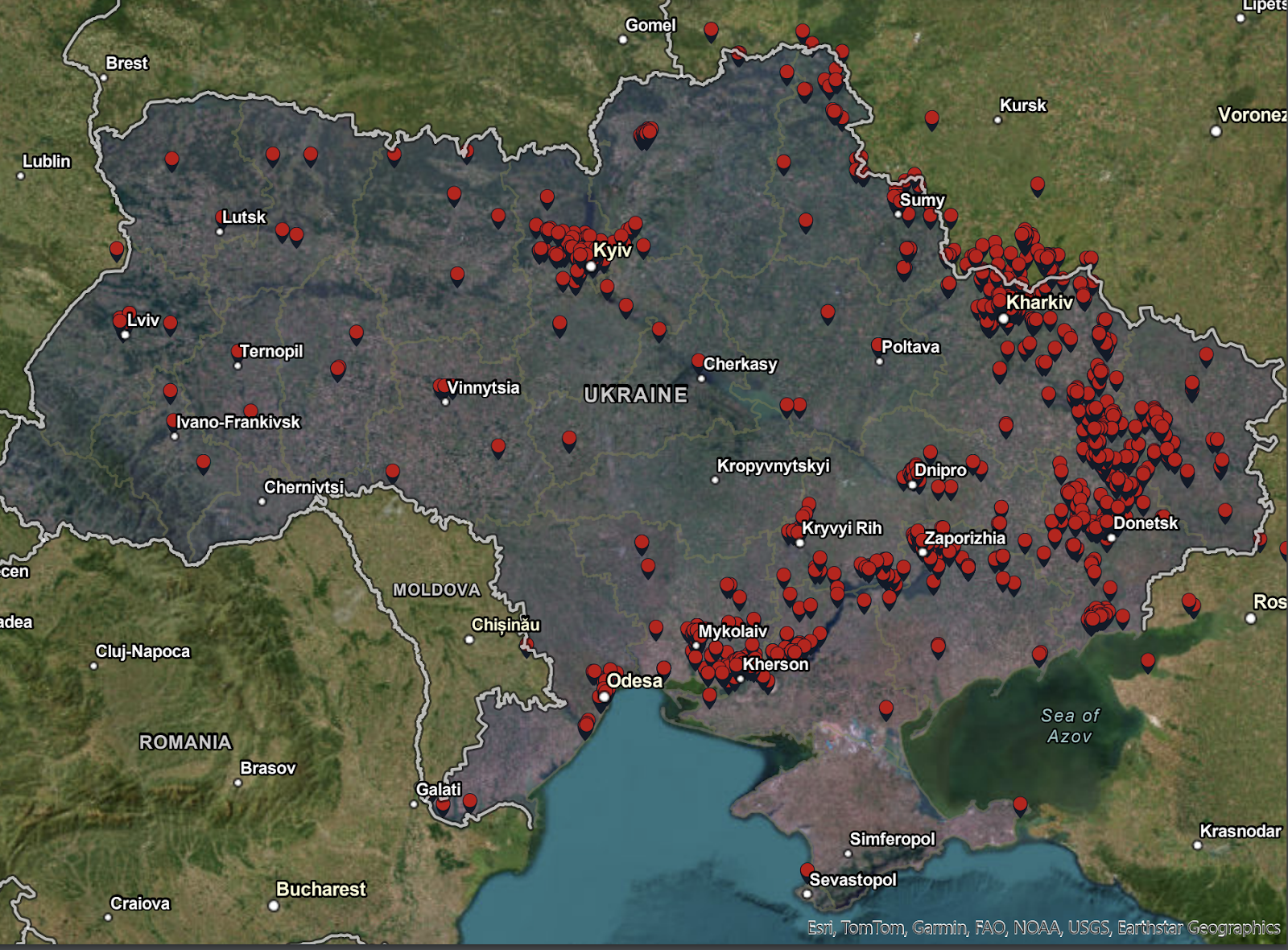

Geolocated and authenticated locations of civilian harm in Ukraine, downloaded from Bellingcat’s “Civilian Harm In Ukraine” interactive map, mapped in ArcGIS Online. Image source: ESRI, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS, Earthstar Geographics, Bellingcat

By Nicholas Azulay

The day of the missile attack in Kramatorsk, just two months after Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion, the station was filled with families—including children—in the process of fleeing.

A single Tochka-U missile launched at the station produced 50 submunitions that in turn each spewed out 316 metal fragments at high velocity. Those cluster munitions killed at least 58 people and wounded more than 100 more with a viciousness rarely seen in a single attack, according to Human Rights Watch.

Even before Ukraine could count their dead and survey the devastation, an onslaught of disinformation flooded news sites and social media channels. The challenge of documenting who was responsible—for both the attack and the ensuing propaganda—would fall to a small army of NGOs and Open Source (OSINT) researchers.

Journalists, researchers, and investigators racing to document the most serious abuses during the war believe that investigating crimes is critical not only to combating disinformation within a hostile information environment, but also to providing a roadmap to accountability.

An Indiscriminate Attack

The grotesque nature of the attack—civilians indiscriminately targeted by cluster bombs—outraged Ukrainians.

“They’re such horrible weapons,” said Sam Dubberley, the Director of Human Rights Watch’s Technology, Rights & Investigations Division. “They’re such perfidious weapons with that kind of indiscriminate nature.”

Worse, carefully planned Russian disinformation campaigns immediately sowed doubt about who launched the attack. Ukraine’s highly visible President Volodymyr Zelensky was attempting to rally Ukrainians to fight the then only weeks old Russian invasion. Proving that Russia—and not Ukraine’s own military forces—perpetrated the attack, was of existential importance.

“Russian propaganda said that this was [the] Ukrainians,” said Iryna Subota, a Ukrainian disinformation expert.

Subota, who previously worked at The Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security housed within the Ukrainian government’s Ministry of Culture, spoke about the pre-meditated nature of the disinformation campaign.

“[The Russians] published the news about the strike on Kramatorsk some minutes before the strike happened,” said Subota. “This is one more example how they connect their information warfare and their real physical war against Ukraine.”

“A lot of news organizations were there, reported on it, assumed it was Russia, and trotted off to other things as they rightly should,” said Dubberley. “I think we felt we could spend a bit more time with this.”

Dubberly’s team produced Human Rights Watch’s authoritative report on the attack—which features 3D models and visual analysis powered by advanced digital and on-the-ground research methodologies.

“We wanted to fight against this kind of Russian disinformation, and we felt it was a space where we could actually drive some change,” said Dubberley. The Human Rights Watch team was able to prove that Russia controlled the area from where the missile was launched and was in possession of the exact cluster munitions used.

“Russian propaganda claimed that Ukrainians shelled it, Ukrainian sources claimed that Russians shelled it,” said Mykyta Vorobiov, a young Ukraine-born journalist and researcher now based in Berlin. “But Human Rights Watch actually investigated who shelled it.”

A Growing Investigative Network

For Vorobiov, Human Rights Watch sets a gold standard of human rights investigations.

“They have the best visualization of data I have ever seen,” said Vorobiov. “They visualized without graphic content the [path] of the rockets. It’s absolutely fabulous.”

“The biggest thing about visual investigations is they’re very compelling,” said Evan Grothjan, a researcher at SITU Research, a visual investigations outfit that frequently partners on digital investigations with Human Rights Watch. Grothjan worked closely with Human Rights Watch on another project documenting crimes in Ukraine, this time in Mariupol.

Grothjan, who has a background in filmmaking and formerly worked at The New York Times, recalled how new technologies were hailed as the end of war because of their ability to communicate their true horror.

“[But] the more information we got, didn’t suddenly make these things better,” said Grothjan. “It just made them overwhelming in a different way, and I think visual investigations or this moment we’re in now is just the current response to that.”

Human Rights Watch is among the small army of NGOs investigating, documenting, and disseminating research on war crimes in the country.

But while Human Rights Watch spent months investigating what happened in Kramatorsk, battles continued to rage on social media platforms like Telegram, which has become ubiquitous with the rapid dissemination of conflict imagery.

“Telegram became the source of information for most Ukrainians,” said Vorobiov. “Journalistic standards in Ukraine degraded because of this, because [accounts] can publish and say whatever they want without being journalistic and neutral.”

Still, digital open source intelligence (OSINT) communities and accounts proliferated.

One OSINT project, DeepStateMap (DeepStateUA on Telegram) has nearly 800,000 followers. Unlike Human Rights Watch, DeepState has direct ties to the Ukrainian government.

The Ukrainian government is well aware of the power of open source imagery. The government hosts an official website for anyone to virtually upload evidence of war crimes, as well as its own think tank-like Center for Countering Disinformation.

Competing Objectives

Independent media’s relationship with the Ukraine government has soured, however. While Ukrainian journalists are vital to efforts to document war crimes, they feel increasingly pressured to comply with government censors and dominant narratives.

“They cannot write anything that differs from the government’s position,” said Vorobiov. “Every time when a person publishes something which in my opinion aligns to a standard of neutrality, like Human Rights Watch, that person gets accused of […] not choosing a side.”

Like independent Ukrainian media asking difficult questions of its government, Human Rights Watch also has a strained relationship with Ukrainian public opinion.

Pro-Ukraine advocates, including many in online OSINT communities, supported the United States’ plan to provide cluster munitions (the same type of weapon used in the attack on Kramatorsk) to Ukrainian forces. The United States’ most recent efforts to supply landmines to the country has seen similar support.

Human Rights Watch’s blatant opposition highlights a noticeable tension between investigators like those at Human Rights Watch, for whom ending the use of cluster munitions and other indiscriminate weapons represents an organizational priority, and amateur investigators who chiefly want Ukraine to win.

“The harsh reality of that is if you use cluster munitions in Ukraine, whoever is using them, they will harm civilians, be it today, tomorrow, five years time,” said Dubberley.

Similar controversy ensued when Human Rights Watch published a report warning that Ukrainian and Russian military bases were too close to civilian objects, a violation of international law. Critics derided the findings, some of which were backed by digital satellite imagery, as equivocating Russian and Ukrainian endangerment to civilians. Amnesty International, which published a similar report, faced particularly harsh criticism on social media.

Perhaps then it is no surprise that Human Rights Watch’s reporting in Kramatorsk strikes its most resounding chords in the personal anecdotes, like those shared by Alina Kovalenko who lost her mother Tamara. Tamara was a retired electrical engineer who had a passion for planting roses. Alina wants those responsible for her mother’s death to be held to account.

When asked about the future of digital forensic investigations despite hostile information environments, Grothjan is optimistic about the ability to tell human stories. “I hope that [this] is able to keep blossoming and digital investigations can really continue to be on the local level, working with activists and victims and victims’ families,” said Grothjan.