By Mónica Adame

I met Gaspar Orozco during my first event as public relations coordinator for the Mexican Consul General in New York almost three years ago. Our boss, the head of the Consulate, invited Mexican artists living in the city to a dinner of Papaya King’s hotdogs, tropical drinks and champagne at the official residence.

I was setting a vase with flowers on the dinner table and making sure there were enough napkins and plates for the guests when Mr. Orozco emerged through the kitchen door, looking at me with a mocking smile on his face. I was performing domestic chores in a brown, business chic dress and matching high heels.

“I suppose someone has to do it, right,” he said. “I’m happy doing it,” I replied, but he had already turned away. Guests began to arrive and we went back to our jobs without talking for the rest of the evening. He knew well the artists and mingled effortlessly. After all, he is a career diplomat and a poet.

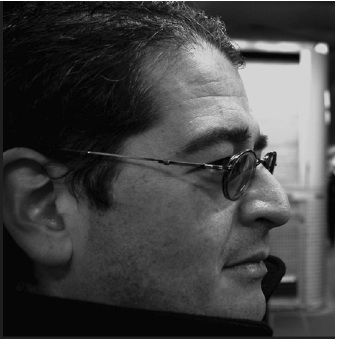

Mr. Orozco looks conventional, but he is an unusual bureaucrat. He is of medium stature, has light skin and receding hairline. He hides his small eyes behind tinted, round glasses that make them look different shades of green and brown depending on the light. Physically, he appears to pose no threat. He, nevertheless, walks a thin line between his creative, liberal beliefs and his job as public official.

Born in the northern state of Chihuahua in the early seventies, long before it gained notoriety for drug violence, he grew up listening to The Beatles, Bob Dylan and The Rolling Stones, and reading his father’s vast library; particularly, his book collection on Chinese literature.

Music got him into trouble in elementary school. At age 12, he started a band playing The Beatles and decided to write a song against professors. “I was testing limits,” Mr. Orozco, laughing on the phone, remembered. He was not allowed to register for the following academic year and had to change schools.

In 1994, when the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) declared war against the Mexican government to protest the economic and social conditions of peasants and indigenous peoples in the southern state of Chiapas, Mr. Orozco and his punk rock band Revolucion X sang in support:

So there is no guerrilla in Mexico

So here that no human rights are violated

Here that everything got solved with NAFTA

EZLN, EZLN, EZLN

“I was attracted to this genre for being the most radical form of popular music, with social and political content and extremely anti-authoritarian,” Mr. Orozco said.

Influenced by his father’s love to prose and philosophy, Mr. Orozco studied Communications and Chinese at the University of Texas at El Paso and later worked as a journalist for the daily “Diario de Juarez.” He translated Chinese poetry to Spanish and in 2000, just as he entered the Mexican Foreign Service, his first book of original poetry “Abrir Fuego” got published.

“Poetry is the thread connecting my life,” Mr. Orozco said. “It’s a pursuit and in each poem, in each book I seek something else. Poetry is my core and where conflict can be solved.” He has published three more books, following a long tradition of writers in the Mexican diplomatic corps. Octavio Paz, Nobel Laureate in Literature in 1990, was also a career diplomat. Mr. Orozco mentions his constant search for that balance between the pen and the sword, recalling the Renaissance ideals: diplomacy as the field for action and literature as the sphere for contemplation.

Mr. Orozco’s latest book titled “Astrodiario” is a collection of poems that refer his daily experiences in Manhattan, the island, and its connection with the stars.

Writing this

The star

Will disappear

Reading this

The star

Will appear

“I believe the poem you write today is not necessarily useful tomorrow. Poems are homes that shelter you today and you abandon tomorrow to build a new one. We have nothing else but the present,” Mr. Orozco said.

His artistic pursuits led him to a new form of narrative expression: film.

Last year, he encountered groups playing Mexican norteña music in the subway – a mixture of Mexican regional music with German and Czech tunes – and decided to make a film. “Subterraneans [the documentary’s title] is a metaphor of the immigration phenomenon: up in the streets, they keep a low profile, hiding at kitchens, always on the back. But under the ground, they explode with all their energy and their Mexican identity,” Mr. Orozco said.

A second project on pirate radio broadcasting, radio stations transmitting out of homes without government’s authorization, is underway. “These stations broadcast cumbias, rock and talk shows. They give voice to the Mexican community and have a huge impact within it,” Mr. Orozco said. “They are also breaking the law.”

Mr. Orozco deals with this contradiction all the time: his ideological convictions and his stance as a Mexican government representative. He, though, affirms the contradiction is tolerable when he is able to improve the lives of Mexican immigrants.

Since 2005, the Mexican government grants scholarships to fund Mexican students at the City University of New York (CUNY) regardless of their immigration status. Mr. Orozco contributed to this effort. “He was very interested in helping the community and understood its dynamics,” said Jesus Perez, Director for Academic Advisement at Brooklyn College.

“He is a complex being,” Mr. Perez, laughing, said. “Working with him, I quickly realized he knew how to deal with bureaucracy and politics and how to use them to achieve his objectives.”

Mr. Orozco and I briefly spoke to each other during the four months I spent at the Consulate. We seemed to have nothing in common other than our nationality and I always perceived him as distant and detached.

Before another Consulate event, I was setting tables and checking the wine inventory when Mr. Orozco approached me.

“You truly enjoy performing a menial job,” he stated sarcastically, without bothering to ask whether I found my work fulfilling. He kept a cool poise lifting his chin in a snobbish attitude. He sat down on a bench and I joined him. “You’re right. This is a stupid job,” I conceded. For the first time, I had said it out loud.

I resigned weeks after and applied to graduate school. Whether or not he had intended to, he had incited a small revolt.