BY LAUREN SCHULZ

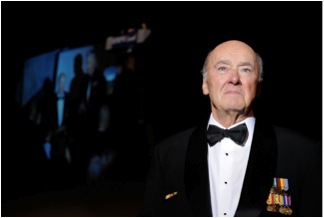

NEW YORK – I met Allen Striffler for the first time on the steps of the New York Athletic Club in the fall of 2009. We had both just left a gala where Allen was being honored. I was in my military dress uniform and Allen was wearing a tuxedo. His ribbons were pinned to his lapel. A black limousine was waiting for him. He didn’t speak much at the gala; when he did, the civilians and service members listened intently.

It took almost 60 years before Allen was ready to talk about the battles of Roi-Namur, Tinian, Saipan and Iwo Jima. During the battle of Iwo Jima, Allen was wounded but returned a day later, just in time to see the flag raised on Mount Surabachi.

In the last few years Allen has been honored at military galas, parades, schools and veteran events across the country. After ignoring his World War exploits for sixty years, Allen has, in a way, rejoined the Marines. Once a Marine always Marine.

In 1941, at 17 years old, Allen decided he was going to join the best branch of service. He forged his parents’ signatures and joined the Marines.

He was sworn in on the steps of City Hall, in downtown New York City with a few others. Shortly after the ceremony the recruits boarded a train out of Penn Station. They were headed to Parris Island, South Carolina for basic training.

A Marine in uniform awaited on the platform in Washington, D.C, outside a dirty troop transport. “You maggots, hurry up,” the sergeant screamed.

“This train was like the ones that carried prisoners during the Civil War,” Allen explained during an interview at his home in Rye, New York. “Smoke was coming out of the windows and there was soot on the floor.” He paused, “That was my first experience with a drill instructor.”

They finally arrived at Parris Island and spent eight weeks training. “I remember the first night and they played taps, some kids started crying and I yelled at them ‘Get the hell out of here, you aren’t going to be Marines.’”

At that moment, Allen thought to himself that he was going to be the best. Thinking back to his days at Parris Island, the now 86-year-old man smiled, squinted his light blue eyes and laughed. “That didn’t turn out, there were a lot of other young [recruits] that wanted the same thing,” he said

Allen spent two weeks on the rifle range and a lot of time running and working out. The drill instructors didn’t talk about the Japanese or about the German Army. The only talk about the war came from Hollywood. “Everyone thought John Wayne was going to win the war,” he said.

At the end of the eight weeks the recruits could call themselves Marines. Each was handed a piece of paper from the drill instructor that said where they would be going next. Allen was headed to California where he would learn to be a radio operator.

By January 1944, Allen was attached to Headquarters Battalion, 23rd Regiment, 4th Marine Division. The “Fighting 4th” was preparing to leave from San Diego, heading straight to the Marshall Islands.

“Prior to our leaving, 1st Division was just coming back from the Panama Canal. They looked like canaries, eyes were yellow, and skin was yellow from taking sulfur pills. A couple were brought in to tell us how this was not a common enemy. Fright is what I learned from them,” Allen said, as his voice became soft and he looked away.

“We were looking up to them and had established what it meant to be a Marine. Like talking to a big brother. Sometimes they would stop and wander and we new they were going back to what they had been through.”

The 4th Division set sail and arrived at the Marshall Islands late January 1944.

“I have a little trouble bringing back the Marshall Islands,” he said. “It was very noisy at times and very quiet at others.

Allen’s division secured the Marshall Islands and was sent back to Maui, the home base. By June, they were headed to Saipan and Tinian. By the end of July, both islands were secure. The fighting was grueling and 30 percent of the division was wounded or killed.

“After each [battle] you were anxious to see who would come back. Then you would have replacements. You were looking at them and thinking to yourself you are replacing my friend,” said Allen. The replacements were outcasts at first, but that didn’t last too long. They soon assimilated into the unit.

By February 1945 Allen was back aboard ship and headed to Iwo Jima with his unit, a 15 or 16-day sail from Maui.

Allen remembers the landing crafts all over the place, the black sand, and the red and green flashes from the battle ships firing. “The shells looked like garbage cans,” he said.

A Marine next to him on the landing boat said “Isn’t that pretty?” Again, with a slight grin and soft chuckle, Allen laughed remembering, “I figured I would go with him because he isn’t going to let anything bother him.”

He doesn’t remember sleeping or taking care of his personal hygiene. He couldn’t recall where he went to the bathroom or how he shaved. Like any battle, Allen explained, once the lines were established, day and night all blend together. He did remember drinking coffee though.

“We would cook the coffee in our helmets,” he said. The smell brings him back from time to time.

Four days into the battle Allen was hit with shrapnel. His shoulder, forearm and foot still have the scars. A corpsman took him off the island to a troop transport ship with wounded men stacked six racks high. After four days of fighting, the hospital ships were already full.

“The worst I saw that bothered me so much [was when] I opened my eyes and looked across at a young Marine hit in the face with a grenade – so full of morphine – all you could hear was his moaning,” he said.

At that moment he knew he had to get back to the fight. Allen said he kept thinking about his friends. They were closer to him than his actual brothers.

He climbed off the makeshift hospital boat and jumped down into the water on one foot. He didn’t have a weapon or a pack, and all he remembers carrying was a white Navy blanket from the boat. He laughed. “I have no idea why I had that blanket. Why didn’t I carry a bulls eye for Christ sake?”

When Allen got onto the beach he spotted an officer. At that time the only way to tell an officer was by the ink marks on his shirt.

“I walked up to him and said I am looking for headquarters 1/23, do you know where they might be?” The officer replied, “ I don’t have a fucking idea where they are, but if you don’t find them your ass is mine because I need people.”

“I found them,” Allen said. With his foot and arm bandaged he was able to continue to fight.

By day 18 or 19, Allen was in his foxhole with his friend Jimmy Jarvis.

“Sitting on the edge of a hole, we heard a couple of quick pops and Jimmy pushed me in and jumped on top of me,” Allen said. “The explosion spread out over us, all the dirt sprayed, and I thought we were hit.” Allen’s voice got quiet, and he paused, “If he hadn’t pushed me in I would be dead.”

When they came home from Iwo Jima, Allen had some more time on his contract. He was sent to China to help with the Japanese refugees. From there he came back to New York and got a job the second day he was home. He moved into Manhattan and quickly established himself as a businessman. Allen worked as a broker for oil companies. He wore tailor-made suits, dined at the finest restaurants and drank at the best clubs.

Only after several years as a retired grandfather did the doors to his memory open. Living in Rye, New York, Allen saw in the paper that a military fair was coming to a nearby park.

Allen thought to himself, “I should go over and take a look and see what it was all about.” As he was walking through the crowd he overheard one young man say to a group that he had some sand from Iwo Jima.

Allen, smiling once again, stopped in front of the group and said to the man with the sand, “so do I – I still have it in my shoes.”

“And that is how it all started, to be able to say that opened up a door and let me go back,” said Allen. “My life today is wrapped around my family, and now I have my Marine Corps family. I think about them all the time.”