BY STIG ARILD PETTERSEN

The smiling face of a tanned young woman with short black hair suddenly peeps out of the apartment door next to the bell I’ve just rung. She’s Olga and I’m Stig and we’re both happy to finally meet each other. She takes me through the living room, painted white like the rest of the apartment. It has no furniture, just heaps of colorful pillows and blankets spread out on the floor, and a bright red hammock strung between two of the walls.

We enter the kitchen, and Olga introduces me to her three other guests, offers me a beer, lights a cigarette and starts folding the clothes that have been hanging to dry at one end of the long kitchen table.

“Nice apartment,” I say.

“Wait till you see El Parche,” she replies. “You’ll love it, it’s such a cool place. We’re going over as soon as the kids are in bed. ”

Olga Robayo, 38, moved back to Bogotá about a year ago, bringing along her two boys aged nine and twelve. After more than a decade studying and working as an artist in Norway, she realized that her work could have more of an impact in her native Colombia.

“It’s a paradox that it’s so much easier to make it as an artist in Norway, while it’s Colombia that really needs people like us,” she says, mixing Norwegian, English and Spanish words as she speaks. “Art is an important tool to fix this messed up country.”

Together with her husband Marius Wang, Olga secured some Norwegian funding and found an empty top floor apartment in La Macarena, a progressive neighborhood in the slope of Bogotá’s hillside. The tenant couldn’t afford the rent, since his ambitious cannabis plantation on the large rooftop terrace had failed. Olga offered him to stay for free for the next few months if he helped to shine the place up. Then, after three months of refurbishing, Olga and Marius opened “El Parche Residency”, an art collective where some artists stay for weeks, but most just come and go as they like.

“Can you feel it?” she says enthusiastically as soon as we enter the collective, where one group of people is busy putting empty frames on the white walls while another is sitting at a table assembling an art book with needles and treads. “Isn’t there a great vibe here? There is something special about this place. Did I tell you that it was a Hare Krishna temple before? That’s why. The people left, but the good vibes are still here.”

El Parche, meaning a group of friends in Colombian slang, has become just what Olga wanted. In a country where people enter politics for personal enrichment and the affluent are busy rallying for the archconservative president’s third consecutive term, progressive and critical artists trying to change society have a hard time finding the funding needed to explore their talents. El Parche gives them just that.

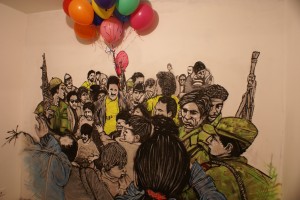

“Good question,” says Lorenzo Masneh when I ask him what he would have been doing if it wasn’t for El Parche. The young graffiti artist is putting a final touch on a wall painting depicting Presidents Uribe of Colombia and Chavez of Venezuela as green vampires. His exhibition “Nuevos Tiempos” featuring political art through graffiti and walls covered in newspaper clips is set to open the following night. “I probably would still be working as a bar tender in New York to make some money. Olga created a reason for me to come back to Bogotá, and a platform to try to influence Colombian society through my art. Here I can spend the whole day sharing my creativity with other people. I just love it.”

Olga herself is running around trying to document the preparations with a digital SLR, complaining that she has no idea how to take pictures. But until her husband, the photographer, shortly returns from Holland where he is finishing his studies, she’ll be doing the job anyway.

“That’s what Colombia needs, you know. People like Lorenzo,” Olga says. “But El Parche isn’t just important to Colombia, it’s also important to Norway. I want people from all over the world to come here and see that Colombians can make more than just cocaine and bananas, that we are people too.”

Europeans in general know little about South American art, according to Olga. When they talk about an international art scene, the big European capitals and New York is normally what’s on their minds. In South America, they expect only to find traditional art influenced by indigenous culture or the Spanish colonial era. This probably has a lot to do with Colombian artists’ lack of outreach opportunities. There are only a couple of other art collectives in Bogotá, and El Parche is the only one which artists can use without paying.

So far Olga has persuaded a handful of skeptical Norwegian artists to stay and work for a few weeks at El Parche. Prejudice and horror stories scare many from coming to Colombia, but things are changing, she says. Those who go back after a successful stay tell their countrymen of a progressive art scene, lovely people, safe streets and cheap weed, the last thing being the only benefit they expected.

“What I hope they bring back is an understanding of why Colombian art is the way it is,” she says. “I want them to see how people live here, and that it relates to their lives in the Norway. People have to understand that they live a comfortable life in the North partly because people are suffering in the South. Hadn’t it been for poor labor rights and paramilitary groups in Colombia, Chiquita Bananas wouldn’t be so cheap in Norway. That’s what international art should really be about, and you don’t find that in London, Paris or New York.”