Morsi: Dictator, Rebalancer, or Both?

A very interesting conversation on Warren Olney’s To the Point over the implications of Morsi trying to take control. On the one hand, he actually has a mandate, public support, and a known ideology. On the other hand, the Muslim Brotherhood and now Morsi, during the transition, have time and again made self-serving power grabs and exhibited a propensity for authoritarianism. Listen here for a sometimes sharp debate involving me, Marc Lynch, Ehud Yaari, and Kareem Fahim.

Everybody’s an Islamist Now

The case that a political term has outlived its usefulness

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

To watch the Arab world’s political transformation over the past year has been, in part, to track the inexorable rise of Islamism. Islamist groups—that is, parties favoring a more religious society—are dominating elections. Secular politicians and thinkers in the Arab world complain about the “Islamicization” of public life; scholars study the sociology of Islamist movements, while theologians pick apart the ideological dimensions of Islamism. This March, the US Institute for Peace published a collection of essays surveying the recent changes in the Arab world, entitled “The Islamists Are Coming: Who They Really Are.”

From all this, you might assume that “Islamism” is the most important term to understand in world politics right now. In fact, the Islamist ascendancy is making it increasingly meaningless.

In Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, the most important factions are led overwhelmingly by religious politicians—all of them “Islamist” in the conventional sense, and many in sharp disagreement with one another over the most basic practical questions of how to govern. Explicitly secular groups are an exception, and where they have any traction at all they represent a fragmented minority. As electoral democracy makes its impact felt on the Arab world for the first time in history, it is becoming clear that it is the Islamist parties that are charting the future course of the Arab world.

As they do, “Islamist” is quickly becoming a term as broadly applicable—and as useless—as “Judeo-Christian” in American and European politics. If important distinctions are emerging within Islamism, that suggests that the lifespan of “Islamist” as a useful term is almost at an end—that we’ve reached the moment when it’s time to craft a new language to talk about Arab politics, one that looks beyond “Islamist” to the meaningful differences among groups that would once have been lumped together under that banner.

Some thinkers already are looking for new terms that offer a more sophisticated way to talk about the changes set in motion by the Arab Spring. At stake is more than a label; it’s a better understanding of the political order emerging not just in the Middle East, but around the world.

THE TERM “ISLAMIST” came into common use in the 1980s to describe all those forces pushing societies in the Islamic world to be more religious. It was deployed by outsiders (and often by political rivals) to describe the revival of faith that flowered after the Arab world’s defeat in the 1967 war with Israel and subsequent reflective inward turn. Islamist preachers called for a renewal of piety and religious study; Islamist social service groups filled the gaps left by inept governments, organizing health care, education, and food rations for the poor. In the political realm, “Islamist” applied to both Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, which disavowed violence in its pursuit of a wealthier and more powerful Islamic middle class, and radical underground cells that were precursors to Al Qaeda.

What they had in common was that they saw a more religious leadership, and more explicitly Islamic society, as the antidote to the oppressive rule of secular strongmen such as Hafez al-Assad, Hosni Mubarak, and Saddam Hussein.

Over the years, the term “Islamist” continued to be a useful catchall to describe the range of groups that embraced religion as a source of political authority. So long as the Islamist camp was out of power, the one-size-fits-all nature of the term seemed of secondary importance.

But in today’s ferment, such a broad term is no longer so useful. Elections have shown that broad electoral majorities support Islamism in one flavor or another. The most critical matters in the Arab world—such as the design of new constitutional orders in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya—are now being hashed out among groups with competing interpretations of political Islam. In Egypt, the non-Islamic political forces are so shy about their desire to separate mosque from government that many eschew the term “secular,” requesting instead a “civil” state.

In Tunisia’s elections last fall, the Islamist Ennahda Party—an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood—swept to victory, but is having trouble dealing with its more doctrinaire Islamist allies to the right. In Libya, virtually every politician is a socially conservative Muslim. The country’s recent elections were won by a party whose leaders believe in Islamic law as a main reference point for legislation and support polygamy as prescribed by Islamic sharia law, but who also believe in a secular state—unlike their more Islamist rivals, who would like a direct application of sharia in drafting a new constitutional framework.

In Egypt, the two best-organized political groups since the fall of Mubarak have been the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi Noor Party—both “Islamist” in the broad sense, but dramatically different in nearly all practical respects. The Brotherhood has been around for 84 years, with a bourgeois leadership that supports liberal economics and preaches a gospel of success and education. The rival Salafi Noor Party, on the other hand, includes leaders who support a Saudi-style extremist view of Islam that holds the religious should live as much as possible in a pre-modern lifestyle, and that non-Muslims should live under a special Islamic dispensation for minorities. A third Islamist wing in Egypt includes the jihadists—the organization that assassinated President Anwar Sadat in 1981, which has officially renounced violence and has surfaced as a political party. (Its main agenda item is to advocate the release of “the blind sheikh,” Omar Abdel-Rahman imprisoned in the United States as the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.)

“ISLAMIST” MIGHT BE an accurate label for all these parties, but as a way to understand the real distinctions among them it’s becoming more a hindrance than a help. A useful new terminology will need to capture the fracture lines and substantive differences among Islamic ideologies.

In Egypt, for example, both the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis believe in the ultimate goal of a perfect society with full implementation of Islamic sharia. Yet most Brothers say that’s an abstract and unattainable aim, and in practice are willing to ignore many provisions of Islamic law—like those that would limit modern finance, or those that would outright ban alcohol—in the interest of prosperity and societal peace. The Salafis, by contrast, would shut down Egypt’s liquor industry and mixed-gender beaches, regardless of the consequences for tourism or the country’s Christian minority.

There’s a cleavage between Islamists who still believe in a secular definition of citizenship that doesn’t distinguish between Muslims and non-Muslims, and those who believe that citizenship should be defined by Islamic law, which in effect privileges Muslims. (Under Saudi Arabia’s strict brand of Islamist government, the practice of Christianity and Shiite Islam is actually illegal.) And there’s the matter of who would interpret religious law: Is it a personal matter, with each Muslim free to choose which cleric’s rulings to follow? Or should citizens be legally required to defer to doctrinaire Salafi clerics?

Many thinkers are trying to craft a new language for the emerging distinctions within Islamism. Issandr El Amrani, who edits The Arabist blog and has just started a new column for the news site Al-Monitor about Islamists in power, suggests we use the names of the organizations themselves to distinguish the competing trends: Ikhwani Islamists for the establishment Muslim Brothers and organizations that share its traditions and philosophy; Salafi Islamists for Salafis, whose name means “the predecessors” and refers to following in the path of the Prophet Mohammed’s original companions; and Wasati Islamists for the pluralistic democrats that broke away from the Brotherhood to form centrist parties in Egypt.

Gilles Kepel, the French political scientist who helped popularize the term “Islamist” in his writings on the Islamic revival in the 1980s, grew dissatisfied with its limits the more he learned about the diversity within the Islamist space. By the 1990s, he shifted to the more academic term “re-Islamification movements.” Today he suggests that it’s more helpful to look at the Islamist spectrum as coalescing around competing poles of “jihad,” those who seek to forcibly change the system and condemn those who don’t share those views, and “legalism,” those who would use instruments of sharia law to gradually shift it. But he’s still frustrated with the terminology’s ability to capture politics as they evolve. “I’ve tried to remain open-eyed,” he said.

It’s also helpful to look at what Islamists call themselves, but that only offers a perfunctory guide, since many Islamists consider religion so integral to their thinking that it doesn’t merit a name. Others might seek for domestic political reasons to downplay their religious aims. For example, Turkey’s ruling party, a coterie of veteran Islamists who adapted and subordinated their religious principles to their embrace of neoliberal economics, describes itself as a party of “values,” rather than of Islam. In Libya, the new government will be led by the personally conservative technocrat Mahmoud Jibril; though his party could be considered “Islamist” in the traditional sense, it’s often identified as secular in Western press reports, to distinguish it from its more religious rivals. Jibril himself prefers “moderate Islamic.”

The efforts to come up with a new language to talk about Islamic politics are just beginning, and are sure to evolve as competing movements sharpen their ideologies, and as the lofty rhetoric of religion meets the hard road of governing. The importance of moving beyond “Islamism” will only grow as these changes make themselves felt: What we call the “Islamic world” includes about a quarter of the world’s population, stretching from Muslim-majority nations in the Arab world, along with Turkey, Pakistan, and Indonesia, to sizable communities from China to the United States. For Islam, the current political moment could be likened to the aftermath of 1848 in Europe, when liberal democracy coalesced as an alternative to absolute monarchy. Only after that, once virtually every political movement was a “liberal” one, did it become important to distinguish between socialists and capitalists, libertarians and statists—the distinctions that have seemed essential ever since.

Egypt Briefing on Here & Now

WBUR’s Robin Young continues her show’s valiant effort to keep up with confusion in Egypt. We talked on Friday; you can find the broadcast here.

Egypt’s Fractured Political Class Outgunned by Military

Protesters sing the national anthem as they rally against the dissolving of parliament, at the parliament building in Cairo June 19, 2012. (photo by REUTERS/Asmaa Waguih)

[Read the full story at Al-Monitor.]

From the Mediterranean coast to the desert plateau, Egypt is awash with rumors that have whipped the populace into a state of acute anxiety. Word has spread that a renewed state of emergency is imminent or that the Muslim Brothers plan to deploy a militia to the streets, that families should stock up on fuel or food because of “dark days ahead,” that a curfew will be imposed, that Hosni Mubarak’s death will delay a new president taking office or that last weekend’s election will have to be run again because of massive fraud.

The state of panic points to two sad trends: The military is consolidating power with increasing directness and public support, while the entire civilian political sphere has fractured to a degree that beggars the prospect of effective cooperation. Forget about unity in the face of a crusty military junta flush with victory. The moment for revolutionary system-change might well have passed for now. Instead, we can expect a period of retrenchment, nasty political infighting and polarization, all of which will benefit the authoritarians in charge.

No matter who is designated the winner this weekend (or in the eventuality that authorities indefinitely postpone a ruling on the disputed presidential race), the real victor will be the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF.

Meanwhile, the Muslim Brotherhood, whose candidate decisively won the presidential race by its own count, has promised not to resort to force if the unaccountable electoral authority awards the election to the ex-regime’s candidate, who has promised a “surprise.”

Either way, the next president will take office in the shadow of the ruling SCAF, which has boldly written itself into a position of dominance with a series of arbitrary court decisions and a temporary constitution that extends the military’s control almost indefinitely.

Primary responsibility for all of this mess rests with the military, which introduced a process designed to enervate the public through confusion, uncertainty and a long, constantly shifting timetable. Since Mubarak stepped down, the military has been in complete control. Lest people forget, it is the military that massacred peaceful protesters at Maspero in October 2011, and the military that is responsible for a state media that has peddled noxious sectarian propaganda against the Brotherhood and a xenophobic smear campaign to undermine the revolutionary youth.

No matter the sins of the Muslim Brotherhood and the liberals since they were sworn in as members of parliament in January, it’s important to remember that only the military had the power to drive a political transition, perk up the flailing economy or provide respectable security on the streets. SCAF has failed on all counts.

Nonetheless, the Muslim Brotherhood behaved with reprehensible brittleness and triumphalism. In parliament, it coddled up to the military dictators, refraining from passing legislation to challenge SCAF powers and engaged in majoritarian overreach with its determination to ram through a constitutional convention dominated by Islamists, rather than one built on principles of consensus and universal representation.

And many liberals have chosen to see these freely elected Islamists as a greater threat than the military dictatorship that kills and beats demonstrators, imprisons activists, tries civilians before military courts and insists by fiat or rigged judicial ruling on undoing every single political development that curtails military power.

As Egyptians awaited the decision of the capricious Presidential Election Commission, already delayed to much alarm from Thursday to the weekend, I watched a liberal grandee hector a pair of young revolutionaries. Mohamed Ghonim is a widely respected urologist and polyglot who founded a renowned clinic in the provincial Nile Delta city of Mansoura. Late in the evening at the Books & Beans café bookstore, seated between a baby grand piano and the window, Ghonim wagged his finger at the young men roughly a quarter his age who have spent the last year toppling a dictator, protesting in the streets, and campaigning for the pro-revolution presidential candidates who together took a majority of the vote in the first round but were too fractured to make into the runoff.

“These guys have to learn history and focus on one issue, the constitution, without messing around,” Ghonim said. Ahmed Shafiq, a retired air force general who served as Mubarak’s final prime minister, has promised a restoration of a “state of law” if elected, and is tightly aligned with the worst elements of the old regime’s abuse of power.

Yet Ghonim — like many liberals — appeared unconcerned about a Shafiq victory, stolen or legitimate. He cited Marxist-Leninist theory: The nastier the regime, the greater the clarity and therefore the better for the “second wave of the revolution.” This sort of blithe insouciance about another round of dictatorial revanchism runs deep among liberals, and will serve to further divide and discredit them among both revolutionaries and Islamists.

The SCAF might be comfortable with a Muslim Brotherhood presidency. Their powers are well assured, and they’ll benefit from an Islamist scapegoat in the president’s chair whom they can blame for the coming failures of governance. But the old ruling party apparatus and the police have much more to fear. Under Muslim Brotherhood rule, stalwarts of the National Democratic Party could see their assets confiscated and their local patronage and control machines dismantled. Abusive and once-all-powerful police officials might face prison and certainly can expect to see themselves marginalized or fired from the Ministry of the Interior. For them, this election is an existential contest. Shafiq would save them; Mursi might smite them. Among their ranks they count many of the richest business owners in Egypt, along with the top judges on the Supreme Constitutional Court, who incidentally (and without possibility of appeal!) control the electoral process.

One final matter merits further thought. The entire political class has obsessed about the constitution. What position will it give Islam? Will it stipulate a presidential, parliamentary or hybrid system? The primacy accorded the constitution is puzzling. Of course, the institutions and principles stipulated in the state’s constitution are important, but they are far less determinative than power. Hosni Mubarak eviscerated the rule of law in Egypt despite a decent-enough constitution and theoretical legal framework. The state’s power and intent trump rules. Over the past year and a half, the SCAF has used constitutional declarations, supra-constitutional declarations, the state of emergency and electoral procedures to tie the country in knots. In Egypt today, the law is a joke, issued by generals whose legitimacy is conjured by an unsubstantiated claim of authority, along with the guns that back it up. The courts make a mockery of the law, giving credence to obscene, fabricated complaints against activists filed by ex-regime hacks, dismissing candidates and elected officials on technicalities, exonerating police who kill civilians and contemplating a case to dissolve the Muslim Brotherhood on another technicality.

In fact, the only groups that appear serious about respecting rules and laws are those who have been emasculated by their misuse: the Muslim Brotherhood and the liberal opposition.

The political class appears determined to bring a bunch of lawyers to a gunfight with the SCAF.

Sadly, the moment of revolution has receded and the prospect of serious reform, while still possible, seems at a minimum years away. The malignant malfeasance of Egypt’s security state will continue unabated until it is forced to concede power. Only once the military’s power is stripped and it is sidelined from a transition should elected representatives concentrate their efforts on a new legal blueprint for the state.

Citizens can begin this process by refusing the legitimacy of any decision that comes from the SCAF. The dissolved parliament could meet in Tahrir Square under open air and issue its own constitution and laws. The fairly elected president could convene his cabinet in a café. Revolutionaries could hold sit-ins in government buildings, or better still, on the sidewalks in poor neighborhoods where they could explain their agenda to the wider public.

All this, however, would require a unity of purpose that has escaped a political class in thrall to the narcissism of minor differences, riven by class and sectarian prejudice, and led by craven politicians fatally tempted by the tiny slivers of power tossed to them by the SCAF. Until this mindset changes, we can expect the military to reign smugly over a rebellious but fragmented Egypt.

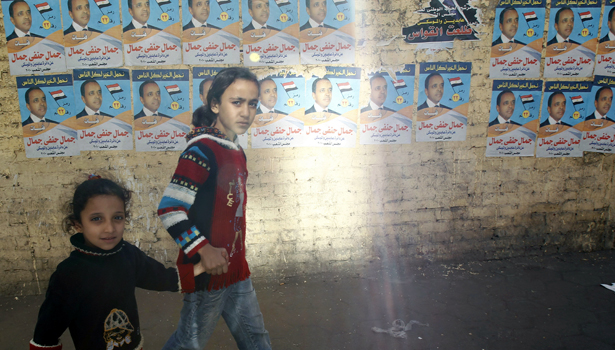

Is Anyone Ready to Actually Lead Egypt?

Girls walk past Muslim Brotherhood campaign posters in Cairo. (Reuters)

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

The Muslim Brotherhood is inflexible and exclusive, the military power-hungry and self-interested, liberals are in disarray, and a country that badly needs cooperation is once again plagued by division.

CAIRO, Egypt — The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi appears to have won Egypt’s first contested presidential election in history, a mind-boggling reversal for the underground Islamist organization whose leaders are more familiar with the inside of prisons than parliament. Whether or not Morsi is certified as the winner on Thursday — and there is every possibility that loose-cannon judges will award the race to Mubarak’s man, retired General Ahmed Shafiq — the struggle has clearly moved into a new phase that pits political forces against a military determined to remain above the government.

The ultimate battle, between revolution and revanchism, will remain the same whether Morsi or Shafiq is the next president. It’s going to be a mismatched struggle, one that will require unity of purpose, organization, and the sort of political muscle-flexing that has escaped civilian politicians for the entire 18-month transition process. If they can’t marshal a strong front on behalf of a unified agenda, they are likely to fail to wrestle the most important powers out of the military’s stranglehold.

After a year and a half in direct control, Egypt’s ruling council of generals (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF) appears to have grown fond of its power. As the presidential vote was being counted, SCAF issued a new temporary constitution that gives it almost unlimited powers, far greater than those of the president. It can effectively veto the process of drafting the new permanent constitution, and it retains the power to declare war.

“We want a little more trust in us,” a SCAF general said in a surreal press conference on Monday. “Stop all the criticisms that we are a state within a state. Please. Stop.”

In fact, all the military’s moves, right up to the last-minute dissolution of parliament and the 11th-hour publication of its extended, near-supreme powers, give Egyptians every reason to distrust it. Sadly, the alternatives are not much more reassuring.

Shafiq, the old regime’s choice, mobilized the former ruling party with an unapologetic, fear-driven campaign, drumming up terror of an Islamic reign while promising a full restoration to Mubarak’s machine. If he ends up in the presidential palace, he could place the secular revolutionaries and the Muslim Brotherhood in harmony for the first time since the early days of Tahrir Square.

Morsi, meanwhile, is known as an organization enforcer, not as a gifted politician or negotiator — which are the skills most in need as Egypt embarks on its high-risk struggle to push aside a military dictatorship determined to remain the power behind the throne.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate has few assets in his corner. He represents the single best-organized opposition group but doesn’t control it. Revolutionary and liberal forces are in disarray. Mistrust, even hatred, of the Muslim Brotherhood has flared among groups that should be the Brotherhood’s natural allies against the SCAF. And the Brotherhood itself has wavered between cutting deals with the military and confronting it when the military changes the terms. Many secular liberals say they relish the idea of the dictatorial military and the authoritarian Islamists fighting each other to exhaustion.

All this division promises a chaotic and difficult transition for Egypt after 18 months of direct military rule. If officials honor the apparent results (an open question, since the elections authority is run by SCAF cronies), Morsi will head an emasculated, civilian power center in the government that will have little more than moral suasion and the bully pulpit with which to face down the SCAF.

While the military’s legal coup overshadows the election results, it doesn’t render them meaningless. The presidency carries enormous authority; managed successfully, it’s the one institution that could begin to counter and undo the military’s evisceration of law and political life.

The example of parliament is instructive. Some observers said from the beginning that a parliament under SCAF would have no real power. But that didn’t turn out to be the problem with the Islamist-controlled parliament. It had symbolic power, and it could pass laws even if the SCAF then vetoed them. What made the parliament a failure was its actual record. It didn’t pass any inspiring or imaginative laws, it repeatedly squashed pluralism within its ranks, and it regularly did SCAF’s bidding. That’s what discredited the Brotherhood and its Salafi allies and led to their dramatic, nearly 20 percent drop in popularity between the parliamentary elections and the first round of presidential balloting five months later.

It would be greatly satisfying if the corrupt, arrogant, and authoritarian machine of the old ruling party were turned back, despite what appears to have been hints of an old-fashioned vote-buying campaign and a slick fear-mongering media push, backed by state newspapers and television. On election day, landowners in Sharqiya province told me the Shafiq campaign was offering 50 Egyptian pounds, or about $8.60, per vote.

But it would be greatly unsatisfying for that victory to come in the form of a stiff and reactionary Muslim Brotherhood leader who appears constitutionally averse to coalition-building and whose political instincts seem narrowly partisan, at a time when Egypt’s political class is locked in death-match with the nation’s military dictators.

Egypt’s second transition could last, based on the current political calendar, anywhere from six months to four years. A new constitution will have to be written and approved, likely with heavy meddling from the military and with profound differences of philosophy separating the Islamist and secular political forces charged with drafting it. A new parliament will have to be elected. And then, possibly, the military (or secular liberals) could force another presidential election to give the transitional government a more permanent footing.

Meanwhile, during this turbulent period, Egypt will have to contend with the forces unleashed during the recent, bruising electoral fights.

Shafiq’s campaign brought into the open the sizable constituency of old regime supporters (maybe a fifth of the electorate, based on how they did in recent votes) and Christians terrified that their second-class status will be grossly eroded under Islamist rule.

Liberals will have to explain and atone for their stands on the election. Many of them said they would prefer the “clarity” of a Shafiq victory to a triumphalist Islamic regime under Morsi, and cheered when parliament was dissolved — appearing hypocritical, expedient, and excessively tolerant of military caprice.

The Brotherhood still hasn’t made a genuine-seeming effort to placate and include other revolutionaries, spurning entreaties to form a more inclusive coalition. It attempted, twice, to force through a constitution-writing assembly under its absolute control. Yet, once more, the Brotherhood has a chance to save itself. So far, at each such juncture it has chosen to pursue narrow organizational goals rather than a national agenda. It would be great for Egypt if the Brotherhood now learned from its mistakes, but precedent doesn’t suggest optimism.

Partisans of both presidential candidates told me they expected a big pay-off when their man won: cheaper fertilizer, free seeds, a flood of affordable housing, jobs for all their kids, better schools. None of these things is to be expected in the near future under any regime in Egypt. Disappointment is sure to proliferate as everyone realizes how difficult Egypt’s long slog will be.

There’s much hand wringing among Egyptians about the last-minute power grab by the military through the sweeping constitutional declaration it published on Sunday. In a land of made-up law and real power, why the obsession with power-mad generals, co-opted judges, and the arbitrary declarations they publish? SCAF’s decisions only matter because of its raw power, tied to the gunmen it has deployed on the streets and its willingness to use them against unarmed civilians. This inequity will only change with a shift in actual power, not because of a clever and just redrafting of laws. An elected president, or a defenestrated parliament for that matter, could issue its own, better constitution and declare it the law of the land, and enter a starting contest with SCAF. Authority belongs to whomever claims it and can make it stick.

Here & Now Egypt Elections Preview

Robin Young at WBUR’s Here & Now talked with me today about the possible outcomes in Egypt and their implications. All predictions are useless at this point; looking forward to seeing the voting tomorrow, and the results next week. Listen here.

UPDATE

Some additional radio appearances about the voting in Egypt. KCRW’s To the Point had Jehan Reda, David Kirkpatrick, Shadi Hamid, Dan Kurtzer and me on yesterday. Listen here. And KUOW talked to Borzou Daragahi and me earlier; listen here.

A Primer on the Arab World’s First Free Presidential Election

A volunteer for Egyptian presidential candidate Amr Moussa folds t-shirts. (Reuters)

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

CAIRO, Egypt — What should we look for after the votes are counted in Egypt this week — or rather, if the ballot box contents are counted, rather than trashed or illicitly augmented?

Once Egyptians go to the polls on Wednesday to choose a president, no matter what happens next, the transition from impermeable autocracy to something hopefully more accountable will move to another, more clarifying, stage.

The integrity of the process will be the first hurdle. And if Egyptian monitors and political parties endorse the count and the turnout is significant, as expected, the results will be the second.

Because opinion polling in Egypt has not yet had a semblance of accuracy and since there is no precedent for a contested presidential election in Egypt, there are simply no meaningful metrics to handicap the race. Many Egypt watchers have picked likely front-runners, but this is nothing more than educated guesswork. My own prediction is that the top three finishers are likely to be Amr Mousa, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh and Mohamed Morsy, and that whichever of the two Islamists makes it to the runoff will win.

But this is little more than high-level gut-work, based on a reading of the parliamentary election results earlier this year, Egypt’s only real election since 1952; an assessment of public opinion and emerging political thought; haphazard street interviews; and the size and quality of crowds at electoral rallies.

The electorate is fragmented, with at least five candidates have attracted significant followings. As a result, that many or more could poll in the double digits. The field is wide open, especially because of the fluid nature of political allegiances in this period of transition. The major constituencies will be split among rival candidates from the same camp: Islamists, revolutionaries, law-and-order nationalists, liberals.

Men sitting at a café during the four-and-half-hour presidential debate a week ago told me they supported both the Muslim Brotherhood and leading secular candidate, Amr Moussa, who is presenting himself as a sort of elder statesman. Some told me they were attracted simultaneously to Hamdeen Sabahi, the secular Nasserist revolutionary favorite, as well as Ahmed Shafiq, the revanchist retired general and Mubarak’s last prime minister. That’s a sign of emerging politics, as voters begin the complex process of ranking their own preferences. How important is a candidate’s connection to the old regime? Position on law-and-order versus reform? Stringency on clerical regulation of civil law? Strategy on reviving Egypt’s moribund economy?

None of the choices are clear-cut, and none of the popular candidates has an uncomplicated constellation of views. For instance, the most Islamist candidate, the Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, is more rigid in his religious views and less sophisticated in his economic ideas than other senior Brotherhood leaders. And the only secular candidate who supported the Tahrir Revolution from the beginning, Hamdeen Sabahi, is also an unreconstructed Nasserist, which is a bit like campaigning in America today as a third-party reformer who wants to bring back Communism.

The top two finishers will go to runoff, to be held on June 16 and 17, which will determine Egypt’s president. Here are a few of the possible outcomes and their likely implications.

Felool runoff: Moussa vs Shafiq. This is the worst of the plausible scenarios, but it’s possible. Thefelool, or “remnants” (meaning leftovers from the old, Hosni Mubarak regime), could prevail. Amr Moussa, the former foreign minister, could finish atop the polls with Ahmed Shafiq, the ex-general who, during his campaign, promised that he would never let a minority group of protesters overthrow a president backed by millions. Never mind that Mubarak said the same thing in his final weeks in power. In this case, Islamist voters and secular revolutionaries would both be likely to take to the streets, convinced that all the political achievements of the Tahrir uprising were under threat. We could expect a tense power struggle with lots of public uproar, and potentially even more uncertainty and violence than we’ve seen over the last year.

Islamist runoff: Morsi vs Aboul Fotouh. The Brotherhood’s Morsi could finish at the top along with the former Brother, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. In this case, we could expect a surge of conditional popular support for Aboul Fotouh, the more conciliatory and moderate of the two — but we should also expect the military, some of the wealthy magnates, and the anti-Islamist secular constituency to bristle and polarize. The non-Islamist politicians might pursue obstructionist tactics, in the belief that their secular principles are under attack.

Glass half full. In this scenario, the runoff features what I call “consensus” candidates, liked by some and acceptable to many, even with reservations. These candidates elicit intense dislike from a minority of Egyptians, but a majority would be willing to live with them. On this list, I’d include Aboul Fotouh, Moussa, and Sabahi. Of the likely outcomes, this is the best; it means that the new president would be unlikely to face a public insurrection, and that he would be able to govern with at least the grudging consent of the majority during the next phase of Egypt’s transition.

Wild card. Given the unpredictability of the process and the split vote, the finalists could include one or two unexpected faces. The revolutionary Sabahi could face Amr Moussa, disenchanting those revolutionaries with an Islamist hue. The reactionary ex-regime Shafiq could face the reactionary Islamist Morsi, leaving a huge swathe of the electorate without a simpatico candidate. The ruling generals could mistrust both finalists and organize a more concerted power grab.

Whichever two candidates make it to the run-off, the very fact that a genuine presidential contest is taking place has irreversible historic implications. Egypt is writing a new political history for itself, an inevitably messy process. Any outcome (short of a Shafiq victory) will likely represent a marked improvement from political life under Mubarak. And whatever the results, the politicization of the electorate will continue, and the public is unlikely to forfeit its newfound sense of ownership over the government.

Inside the Three-Way Race for Egypt’s Presidency

Leading Egyptian presidential candidates Amr Moussa, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, and Mohamed Morsi. / Reuters, AP

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

CAIRO — Egypt’s first real presidential contest ever, for which the candidates met last night for the Arab world’s first-ever real presidential debate, has all the makings of a genuinely interesting fight. The front-runners nicely capture a wide stretch of the spectrum, while leaving out the extremes. Voter interest appears high, and the military rulers seem unlikely to allow major fraud based on their record with parliamentary elections.

But enthusiasm about the debate should not obscure the unsatisfying circumstances of the presidential election, which itself does not guarantee a full transition to civilian rule or democracy.

The president’s powers still have not been delineated, and the significance of the race and its victor could be heavily tarnished by future decisions about the assembly that will write the next constitution, among other unresolved questions about whether Egypt will have a presidential, parliamentary, or hybrid system.

Islamists have proven themselves to be the dominant political bloc, garnering more than two-thirds of the vote in parliamentary elections earlier this year. The winner of the presidential race, even if he is secular, will owe his victory to Islamist voters, and will have to govern in tandem with a parliament that has a veto-proof Islamist majority. Islamist politics are malleable and by no means monolithic, but they will drive the political agenda after decades of total exclusion.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF, has heavily manipulated the process, deepening its unaccountable and authoritarian mechanisms of control. Crony-packed courts and the presidential election commission have made a series of arbitrary decisions. Egypt’s next government will have to negotiate artfully to wrest the most important powers out of the hands of generals.

The campaign has galvanized Egyptians. This week, the candidates crisscrossed the countryside in bus caravans, and thousands turned out in even the minutest villages.

“He has a special charisma,” gushed an English teacher named Ahmed Abdel Lahib, during a pit stop by the Amr Moussa campaign in a Nile Delta hamlet called Mit Fares. “Egypt needs a man like him,” he said of the former Arab League secretary-general.

Hundreds of men thronged the candidate, shouting, “Purify the country!” and “We want to kiss you!” In his tailored suit, and carrying the patrician demeanor he honed over decades as Egypt’s foreign minister and then Arab League chief, Musa clambered onto a makeshift stage for his short stump speech (fix agriculture, the economy, and health care, long live Egypt!). Men pushed over chairs and slammed one another into the walls of the narrow alley to get closer to Moussa and touch his sleeve.

The oaths of loyalty felt a tad staged and excessive, but similar displays characterized all the major candidate rallies, and could reflect the old authoritarian rallies, or a desire for a galvanizing leader like Gamal Abdel Nasser, the nationalist colonel who took power in a 1952 coup, or simply the enthusiasm of voters who for the first time in their lives will likely get to choose their president.

Moussa has presented himself as a secular elder statesman who can stand against what he portrays as a power-hungry Islamist tide, personified by the other two front-runners: the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi and the ex-Muslim Brother Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. It is Aboul Fotouh who most worries Moussa’s strategists: he is giving the former minister a run for first place, marketing himself as potential bridge candidate, a “liberal Islamist” who can appeal to Islamists as well as the secular nationalists and revolutionaries who are wary of Moussa’s connections to the old regime.

Thousands of fans in the market town of Senbelawain waited hours on a recent night for Aboul Fotouh, who seems perpetually delayed by traffic (he was late for the historic presidential debate for the same reason). When he arrived, the retired doctor was greeted like a rock star with swoons and chants. Bearded Salafis and women in full-face-covering niqabs jostled with clean-shaven students.

Aboul Fotouh is a more gripping orator than Moussa, with a gruff, gravelly voice that he controls well, shifting cadence to maintain his audience’s attention. “If this country succeeds, the whole Islamic world succeeds,” Aboul Fotouh shouted, provoking cries of exultation. He talked extensively about sharia, in a way apparently calculated to burnish his Islamist credentials while reassuring his left flank that he opposes such literal interpretations as severing the hands of thieves. Aboul Fotouh’s stump speech played to his Islamist base rather than to his revolutionary and secular sympathizers.

A Muslim Brotherhood member in the audience named Yousef Eid Hamid, 38, said he was campaigning for Aboul Fotouh in defiance of his organization’s strict orders to vote for Morsi. “We are not machines,” he said. “You cannot love a candidate, and then just change.”

Backroom deals with the military will likely be decisive in determining how the winner can govern, but retail politics seem to be taking root for now. During Thursday night’s debate, the two front-runners, Moussa and Aboul Fotouh, dug at each other’s records. Aboul Fotouh portrayed Moussa as a corrupt, weak stooge for Mubarak who will continue the old regime’s authoritarian ways. Moussa attacked Aboul Fotouh as a fire-and-brimstone Islamist who founded a radical group in the 1970s and now disingenuously presents himself as a moderate.

Egyptians crammed cafes to watch. During a half-time walkthrough (the debate lasted more than four hours, from 9:30 p.m. to 2 a.m.) at the Boursa pedestrian arcade behind the Cairo stock exchange, I met several people who had voted for the Muslim Brotherhood for parliament but were leaning toward the anti-Islamist Moussa for president.

“I will give the Muslim Brotherhood domestic policy, but I want to keep them far away from security and foreign policy,” said Abdelrahim Abdullah Abdelrahim, 44, an import-export businessman built like a bouncer. “These Islamists want to march on Al Quds” — Jerusalem — “and wage war. It’s not the time for this.”

He went on to mock the Salafi legislator who tried to sound the call to prayer in parliament, and his Noor Party colleague who tried to claim his nose job bandage was really the scar from a politically motivated assault. “People are more tired than before,” Abdelrahim said as he lost another round of dominoes to a friend.

At the presidential rallies in the Delta, I met numerous voters who were shopping or just checking out the opposition. Leftist revolutionaries, committed to minor candidates guaranteed not to reach the second round, listened to stump speeches to consider whom they’d be willing to hold their noses and vote for in a runoff. Confirmed skeptics came, in case they might change their minds.

Arguments broke out. At the end of one Moussa pit stop in Dikirnis, an older man dismissed the candidate as a “felool,” or remnant of the old regime. Another man pushed him hard in the abdomen: “He is not a felool! Amr Moussa is a great man!” The critic scuttled off to his nephew’s pastry shop, where he continued his invective against Moussa. The nephew, 37-year-old Ahmed Burma, smiled benevolently. “My uncle jumped on the revolutionary bandwagon,” he said. “But I’m supporting Amr Moussa. I run a business with 90 employees. Let’s give this guy a chance to work.”

Still, the polls and predictions are little more than guesswork. Most of the voters live without internet or phones and are beyond the reach of the campaigns’ opinion researchers. Egypt has had only one real election in its modern history: the parliamentary ballot that concluded this January. Twenty-seven million people voted, more than two-thirds of them for Islamist parties.

Even with the Islamist vote split between Aboul Fotouh and the Brotherhood’s Morsi, it’s all but assured that one of them will face Moussa in the runoff June 16 and 17. Morsi might fare better than many analysts seem to think, as the Brotherhood deploys its formidable get-out-the-vote operation, which no other campaign can currently match.

The Islamists in parliament haven’t acquitted themselves well, wasting time on fringe religious debates while the economy sinks, deferring to the army on crucial issues such as military trials for civilians, and alienating almost every major constituency in the country other than their own by trying to impose a constitutional convention packed with Salafist and Brotherhood members.

If turnout is as high as it was for parliament (and it might be higher, since the president has always been the commanding figure in Egypt’s modern political system), Moussa would need to convince more than 6 million people, a full third of those who voted Islamist for parliament, to switch allegiance and vote for him. His advisers believe that’s possible.

They also seem to think that Moussa’s year-long bus tour of rural areas will pay dividends, and that their basic selling point resonates with common voters: a pair of safe, experienced hands for a transition.

Nonetheless, Moussa’s strategy smacks of secular liberal wishful thinking, a common affliction among Egypt’s veteran political class in a year and a half of dynamic change. It might just work out for him, but an equally likely scenario would have the voters that propelled Islamists to parliament eager to give someone with their values more of a chance for success than has been allowed by three months of parliamentary machinations under the shadow of the military.

Egypt’s Bumpy Road

WBUR’s Here & Now discussed the precarious mechanics of the transition in Egypt with me today. As the latest turns demonstrate, this is a process with no rules, or as I call them, “fake rules.” Shafiq is out! Shafiq is back. What next? There’s a very real, and destabilizing, possibility that some court declares the entire process invalid since it’s based on the dubious legal authority of the SCAF, and the constitutional declaration that materialized from whole cloth after the March referendum, which blessed a text that largely vanished. Listen to the conversation here.

Who Is Derailing Egypt’s Transition to Democracy?

Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood presidential candidate Khairat al-Shater, who was disqualified from his campaign. Reuters

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

Many Egyptian liberals rejoiced at Tuesday’s news that three of the most polarizing — and popular — presidential candidates, including those representing the Muslim Brotherhood and the ultra-conservative Salafists, would not be allowed to compete. The final ruling from the Supreme Presidential Elections Commission followed a lower court decision a week earlier that disbanded the lopsided and widely detested constitutional convention, which had been forced through by the Muslim Brotherhood and its Salafi allies.

On the surface, the decisions about the presidential race and the constitutional convention both thwart some serious electoral shenanigans by the Muslim Brotherhood and others, but this is hardly progress for liberalism in Egypt. Unfortunately for Egypt’s prospects, both rulings came from opaque administrative bodies with questionable authority and motives. In the case of the presidential commission, there is no avenue for appeal. And in the potentially more important matter of the constitution, a decidedly political question was buried in a layer of obfuscating legalese.

No one in Egypt can explain the rules governing the two most important hinge points in Egypt’s pivot away from authoritarianism: the selection of the president and the drafting of the constitution.

Sadly, it augurs well for the ruling military junta and the increasingly bold coterie of reactionary forces in Egypt — and poorly for all the emerging political factions, from the secular revolutionaries to the most conservative Islamists.

It’s not just that liberal, short-term gains came through illiberal means. It’s that the pair of game-changing decisions call into question what forces, if any, have control over political life in Egypt.

Events are moving so fast that even seasoned Egyptian activists are still spinning. Presidential candidates put themselves forward on April 6. The frontrunners were all controversial: Hazem Salah Abou Ismail, a charismatic Salafi preacher who has criticized military rule but also embraced extreme, at times conspiratorial, political views and wants to implement Islamic law; Khairat Shater, the most powerful man in the Muslim Brotherhood, who broke his own promise that his group would not have a candidate; and Omar Suleiman, the Hosni Mubarak regime’s spy chief, who reversed himself at the last minute and entered the race with the active support of the reconstituted intelligence services.

The presidential election commission invalided ten candidates, including these three front-runners, on technicalities. Sheikh Hazem fell afoul of a rule that he originally supported, thinking it would hurt secular liberals; he was disqualified because his mother — like millions of Egyptians — had taken a second, in this case American, passport. Shater was banned because he served prison time under Mubarak’s rule; he had been convicted of fraud by a military court, almost certainly a fabricated case that was part of the ancien regime witch hunt against the Brotherhood. Suleiman, whose candidacy had caused the most alarm among liberals and Islamists alike, was kicked off the ballot because some of the petition signatures he collected were deemed fraudulent.

The first ruling technically was consistent with regulations, which themselves are a disturbing sign of the nationalist chauvinism ripening in Egypt. The second two sound like trumped-up technicalities, even if their immediate impact is to calm Egypt by removing divisive candidates from the race. Suleiman’s exit is undeniably good for Egypt, but there was a more legitimate process underway in parliament to exclude his candidacy on the merits, because of his prior role as Mubarak’s henchman and vice president. Alleging forged signatures was a signature old regime trick to discredit opponents such as Ayman Nour after he challenged Mubarak for the presidency in 2005.

In Shater’s case, the military regime had issued a pardon for the trumped-up old conviction. One vestige of the old regime, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, gave Shater the green light; another carryover, the elections bureaucracy, vetoed it.

Meanwhile, the constitution-writing farce ground to a halt last week, on April 10, when it was invalidated by the Supreme Administrative Court, a lower court subject to appeal. The Brotherhood and the Salafis had packed the Constituent Assembly with a veto-proof majority of its own members. According to its founding rules (which were dictatorially issued by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces last year), the constitutional committee was supposed to broadly represent Egyptian society. Instead, it was an Islamist monolith, alienating virtually every other imaginable constituency, from the establishment clerics of Al Azhar and the Coptic Church to women, workers, peasants, liberals, and nationalists. Egypt’s many constitutional and legal scholars were notably absent.

A boycott had already weakened the Assembly, which lost legitimacy with all but the staunchest supporters of the Brotherhood and the Salafi Noor Party. But it was dissolved on a technicality. According to the court, the Islamists in parliament aren’t allowed to appoint themselves to write the constitution. The court said the Brotherhood had broken the rules — which is odd, given that the Brotherhood had followed the constitutional process to the letter even while abnegating its spirit.

The ruling leaves the Brotherhood free to appoint another, equally imbalanced and illegitimate assembly, so long as its members are Islamists not already sitting in parliament. The fundamental problem remains — the Brotherhood is able, and appears willing, to behave in the same authoritarian manner as Mubarak’s regime.

What’s really going on here? Who decided to disqualify three presidential front-runners? Who shut down the constitutional process that had been convened, however poorly, by the freely and fairly elected parliament? On what grounds?

In both instances, a group of essentially anonymous and unaccountable bureaucrats radically transformed the political landscape, citing reasons at best opaque and at worst nonsensical, deploying jargon and legalese to set the parameters of Egypt’s future state.

We have no idea, really, who these officials are, whose interests they serve, whether they are acting in good faith, as independent decision-makers, or at someone else’s behest. It’s a replay of the way major decisions were made in Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt, with a charade of faceless government cogs announcing policies rooted in a complex hierarchy of laws while the all-powerful president claimed complete and impartial detachment.

This is what Issandr El Amrani at the Arabist calls “lawfare” in the Egyptian context, and it extends a nefarious precedent, cultivated during decades of dictatorship. From 1954 to 2011, civilians ruled Egypt under a nominally liberal constitution; in practice, those civilian presidents were retired generals who exercised absolute authority through the military and police, all the while ignoring the constitution on the pretext of a decades-long “state of emergency.”

Today it’s a different, more complicated story; there’s evidence that more players than the ruling military junta have a role in these behind-the-scenes decisions. The next two months are crucial. Presidential elections are to begin May 23 and conclude June 17. Field Marshal and acting president Mohamed Hussein Tantawi suggested this week that a constitution must be written in a hurry, before a new chief executive takes over at the end of June. Procedurally, that’s a near-impossibility. A year and a half of posturing and maneuvering will play out in this final stage, when the old and new power players in Egypt will fight for control of the next phase.

The way this election and constitution-writing process is playing out will at best cast a pall over the transition and, at worst, presage a return to outright authoritarian military rule.

The Lost Dream of Egyptian Pluralism

[Originally published in The Boston Globe, subscribers only.]

CAIRO — It might have seemed naïve to an outsider, but one of the great hopes among the revolutionaries who humiliated Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak more than a year ago was that the country’s strongman regime would finally yield to a democratic variety of voices. Both Islamic revolutionaries and secular liberals spoke up for modern ideas of pluralism, tolerance, and minority rights. Tahrir Square was supposed to turn the page on a half-century or more of one-party rule, and open the door to something new not just for Egypt, but for the Arab world: a genuine diversity of opinion about how a nation should govern itself.![]()

“We disagree about many things, but that is the point,” one of the protest organizers, Moaz Abdelkareem, said in February 2011, the week that Mubarak quit. “We come from many backgrounds. We can work together to dismantle the old regime and make a new Egypt.”

A year later, it is still far from clear what that new Egypt will look like. The country awaits a new constitution, and although a competitively elected parliament sat in January for the first time in contemporary Egyptian history, it is still subordinate to a secretive military regime. Like all transitions, the struggle against Egyptian authoritarianism has been messy and complex. But for those who hoped that Egypt would emerge as a beacon of tolerant, or at least diverse, politics in the Arab world, there has been one big disappointment: It’s safe to say that one early casualty of the struggle has been that spirit of pluralism.

“I do not trust the military. I do not trust the Muslim Brothers,” Abdelkareem says in an interview a year later. In the past year, he helped establish the Egyptian Current, a small liberal party that wants to bring direct democracy to Egyptian government. Despite his inclusive principles, he’s urged the dismissal from public life of major political constituencies with whom he disagrees: former regime supporters, many Islamists, old-line liberals, and supporters of the military. He shrugs: “It’s necessary, if we’re going to change.”

He’s not the only one who has left the ideal of pluralism behind. A survey of the major players in Egyptian politics yields a list of people and groups who have worked harder to shut down their opponents than to engage them. The Muslim Brotherhood — the Islamist party that is the oldest opposition group in Egypt, and the one with by far the most popular support — has run roughshod over its rivals, hoarding almost every significant procedural power in the legislature and cutting a series of exclusive deals with the ruling generals. Secular liberals, for their part, have suggested that an outright coup by secular officers would be better than a plural democracy that ended up empowering bearded fundamentalists who disagree with them.

When pressed, most will still say they want Egypt to be the birthplace of a new kind of Arab political culture — one in which differences are respected, minorities have rights, and dissent is protected. However, their behavior suggests that Egypt might have trouble escaping the more repressive patterns of its past.

***

IN A COUNTRY that had long barred any meaningful politics at all, Tahrir’s leaderless revolution begat a brief but golden moment of political pluralism. Activists across the spectrum agreed to disagree — this, it was widely believed, was the very practice that would lead Egypt from dictatorship to democracy. During the first month of maneuvering after Mubarak resigned in February 2011, Muslim Brotherhood leaders vowed to restrain their quest for political power; socialists and liberals emphasized due process and fair elections. The revolution took special pride in its unity, inclusiveness, and plethora of leaders: It included representatives of every part of society, and aspired to exclude nobody.

“Our first priority is to start rebuilding Egypt, cooperating with all groups of people: Muslims and Christians, men and women, all the political parties,” the Muslim Brotherhood’s most powerful leader, Khairat Al-Shater, told me in an interview last March, a year ago. “The first thing is to start political life in the right, democratic way.”

Within a month, however, that commitment had begun to fray. Jostling factions were quick to question the motives and patriotism of their rivals, as might be expected from political movements trying to position themselves in an unfolding power struggle. More surprising, and more dangerous, has been the tendency of important groups to seek the silencing or outright disenfranchisement of competitors.

The military sponsored a constitutional referendum in March 2011 that supposedly laid out a path to transfer power to an elected, civilian government, but which depended on provisions poorly understood by Egyptian voters. The Islamists sided with the military, helping the referendum win 77 percent of the votes, and leaving secular liberal parties feeling tricked and overpowered. The real winner turned out to be the ruling generals, who took the win as an endorsement of their primacy over all political factions. The military promptly began rewriting the rules of the transition process.

With the army now the country’s uncontested power, some leading liberal political parties entered negotiations with the generals over the summer to secure one of their primary goals — a secular state — in a most illiberal manner: a deal with the army that would preempt any future constitution written by a democratically selected assembly.

The Muslim Brotherhood responded by branding the liberals traitors and scrapping its conciliatory rhetoric. The Islamists, with huge popular support, abandoned their initial promise of political restraint and instead moved to contest all seats and seek a dominant position in the post-Mubarak order. The Brotherhood now holds 46 percent of the seats in parliament, and with the ultra-Islamist Salafists holding another 24 percent, the Brotherhood effectively controls enough of the body to shut down debate. Within the Brotherhood, Khairat Al-Shater has led a ruthless purge of members who sought internal transparency and democracy — and is now considered a front-runner to be Egypt’s next prime minister.

The army generals in charge, meanwhile, have been using state media to demonize secular democracy activists and street protesters as paid foreign agents, bent on destroying Egyptian society in the service of Israel, the United States, and other bogeymen.

Since the parliament opened deliberations in January, the rupture has been on full and sordid display. The military has sought legal censure against a liberal member of parliament, Zyad Elelaimy, because he criticized army rule. State prosecutors have gone after liberals and Islamists who have voiced controversial political positions. Islamists and military supporters have also filed lawsuits against liberal politicians and human rights activists, while the military-appointed government has mounted a legal and public relations campaign against civil society groups.

***

THE CENTRAL QUESTION for Egypt’s future is whether these increasingly intolerant tactics mean that the country’s next leaders will govern just as repressively as its last. Scholars of political transition caution that for states shedding authoritarian regimes, it can take years or decades to assess the outcome. Still, there are some hallmarks of successful transitions that Egypt appears to lack. States do better if they have an existing tradition of political dissent or pluralism to fall back on, or strong state institutions independent of the political leadership. Egypt has neither.

“Transitions are always messy, and the Egyptian one is particularly messy,” said Habib Nassar, a lawyer who directs the Middle East and North Africa program at the International Center for Transitional Justice in New York. “To be honest, I’m not sure I see any prospects of improvement for the short term. You are transitioning from dictatorship to majority rule in a country that never experienced real democracy before.”

Outside the parliament’s early sessions in January, liberal demonstrators chanted that the Muslim Brotherhood members were illegitimate “traitors.” In response, paramilitary-style Brotherhood supporters formed a human cordon that kept protesters from getting close enough to the parliament building to even be heard by their representatives.

At a rally for the revolution’s one-year anniversary in Tahrir Square, Muslim Brotherhood leaders preached and made speeches from a high stage to celebrate their triumph. It was unclear whether they were referring to the revolution, or to their party’s dominance at the polls. It was too much for the secular activists. “This is a revolution, not a party,” some chanted. “Leave, traitors, the square is ours not yours,” sang others.

Hundreds of burly brothers linked arms, while a leader with a microphone seemed to taunt the crowd. “You can’t make us leave,” he said. “We are the real revolution.” In response, outraged members of the secular audience tore apart the Brotherhood’s sound system and pelted the stage with water bottles, corn cobs, rocks, even shards of glass.

The Arab world is watching closely to see what happens in the next several months, when Egypt will write a new constitution and elect a president in a truly competitive ballot, and the military will cede power, at least formally. Even in the worst-case scenario, it’s worth remembering that Egypt’s next government will be radically more representative than Mubarak’s Pharaonic police state.

Sadly, though, political discourse over the last year has devolved into something that looks more like a brawl than a negotiation. If it continues, the constitution drafting process could end up more ugly than inspiring. The shape of the new order will emerge from a struggle among the Islamists, the secular liberals, and the military — all of whom, it now appears, remain hostage to the culture of the regime they worked so hard to overthrow.

Ashraf Khalil and Wael Ghonim Write the Egyptian Revolution

My review of the two latest Egypt revolution books is up at The Daily Beast. I discuss Wael Ghonim’s memoir and Ashraf Khalil’s reported book about the uprising.

Two books released this month can help us start to make sense of this puzzle, with detailed accounts of the uprising a year ago and some insight into the institutions and attitudes that shape Egypt’s largely conservative society.

The first is a memoir by Wael Ghonim, the celebrated Google executive who helped spark the uprising with a wildly popular Facebook page dedicated to a middle-class kid beaten to death by the police. Ghonim tapped into a demographic that proved crucial to the Egyptian uprising: upwardly mobile college-educated youth frustrated by Egypt’s stagnation but wary of politics and activism.

As he tells his own story, Ghonim is a driven, socially awkward young man—ambitious but almost allergic to fame. His early clandestine ventures online revolve around building a library of religious recordings called IslamWay.com. He’s offered great sums of money but instead quietly donates it to charity, all while he’s still a teenager. In the years around 9/11, he marries and pursues his dream, which has nothing to do with unseating Mubarak’s tyrannical police regime. No, young Wael wants nothing more than to work at Google, a goal he finally achieves in 2008.

…

For a broader look at Egypt’s transformation, one can turn to journalist Ashraf Khalil’s Liberation Square: Inside the Egyptian Revolution and the Rebirth of a Nation. Khalil’s illuminating reporting situates the revolt in the stultifying decades that preceded it. (I should mention that Khalil is a friend dating back to the days when we were both based in Baghdad.) He spends nearly half his story on the final decades of Mubarak’s crony rule, detailing the pompous ineptitude of the aging dictator with eternally young hair. And he does an admirable job pulling together the threads of the early dissident and activist efforts rooted in the late 1990s.

By the time Khalil gets to the demonstrations of Jan. 25, 2011, we understand why some Egyptians felt they could no longer “walk next to the wall,” as the proverb instructs, and felt they might as well risk death or imprisonment rather than submit to Mubarak’s capricious police state. But we share the wonder of Khalil, and many of the activists he interviews, who even as they promoted an uprising doubted that Egyptians would join them in significant numbers.

The Despair of Egypt

[Read the original post in The Atlantic.]

The state of the revolution in Egypt is today, for me and probably many others watching it closely, cause for rage and despair. The case for despair is obvious: the dumb, brute hydra of a regime has dialed up its violent answer to the popular request for justice and accountability, and has expanded its power. The matter of rage is more complicated: in Egypt, Tunisia, and other Arab countries, it was righteous anger — forcefully but strategically deployed — that brought fearsome police states to their knees. The outrages of Egypt’s regime are still on shameless display. The only question is whether the fury they provoke will make a difference.

When we see the Egyptian soldier enthusiastically stripping a female protester while another kicks her abdomen, rage is a natural response. So too when we see soldiers and their plainclothes henchman cheerfully chuck rocks and chairs from a fifth-floor roof, and in at least one case, piss down below on their fellow Egyptians peacefully protesting in front of parliament, drawn to the streets in part because of the dozens of their comrades already killed by the state. Most enraging of all is the self-righteous, imperious lying that accompanies the industrial-scale state abuse of its citizens. General Adel Emara hectored the Egyptian reporters who tried to question him about last week’s outrages in Tahrir Square, including the blue bra sequence.

Like the American generals in the early years of the Iraq occupation who complained that the nay-saying media was telling mean, inaccurate stories about their swimming success, Emara blamed the media. The Supreme Council for the Armed Forces was protecting the nation and the demonstrators downtown were spreading chaos. “The military council has always warned against the abuse of freedom,” he said, apparently without irony. In statements this week, the military has incredibly claimed that the bands of hundreds or thousands of unarmed protesters are actually a plot to overthrow the state — a grotesque reversal of the truth.

The new prime minister, Kamal Ganzouri, blamed the “counter-revolution” and “foreign elements” for the demonstrations. He also promised no violence would be used against them, even as security forces shot more than a dozen people and beat hundreds of others. No shame here, but perhaps some ulterior plan to discredit protest entirely. An angry response might be the only one possible, the only way potentially to thwart this colossus. Remember the original protests a year ago in Tunisia and Egypt: people billed them as “Days of Rage.”

Why the violence against demonstrators, against women, against foreigners? Apparently the SCAF believes it can intimidate people into submission, that it can succeed where its authoritarian predecessor Hosni Mubarak failed. The death tolls of this year, and the arrest of 13,000 civilians brought before military trial, are measures of the repressive reflexes of the current military rulers. On November 19, police set upon a small group that had camped out on the edge of Tahrir Square, beating them and destroying their tents — and sparking two weeks of street battles that left at least 40 dead and 2,000 wounded. More recently, on December 16 security forces attacked a follow-on protest in front of the parliament building and the ongoing fighting has killed at least 16 people and critically wounded hundreds.

There are few plausible explanations for the recent spasms of violence against nonviolent demonstrators. It’s hard to imagine why state security attacks civilians during periods of calm, sparking new protests and reinvigorating the revolutionary movement. Perhaps the military has a strategy designed to discredit protesters and revolutionary youth, allowing or even engineering street violence which they can then use in the state media to portray activists as hooligans. Or, perhaps, the police and common soldiers have developed such an intense hatred for the demonstrators — who let us remember, succeeded at putting the security establishment on the defensive for the first time in 60 years — that whenever they confront a protest their tempers flare and they lash out.

There’s also a theory that the police, and even some parts of the army, are simply in mutiny, disregarding the SCAF’s orders. Some believe that the SCAF genuinely believes that all protesters are saboteurs, foreign agents, and traitors out to gut the Egyptian state. Some also suggest that the SCAF is simply incompetent, and that each sordid episode of protest, massacre, political agreement, and betrayal is an act in a bumbling melodrama starring a cast of senescent, befuddled generals, most of whom lived their glory days in military study abroad programs in Brezhnev’s Moscow.

Whether there’s a plan or no plan, some of the results are becoming clear. The Muslim Brothers and the Salafis, who dominated the election results so far, have essentially supported the SCAF’s vague schedule to transfer power to a civilian president by summer. Liberals have coalesced around a new demand for a president to be elected immediately and take over by February 11, the one-year anniversary of Mubarak’s resignation. The SCAF has continued its divide and conquer tactics, undermining all dissent in public while meeting in private with politicians from all parties.

All power still rests in the hands of the military, which has designed an incomprehensible transition process clearly engineered to exhaust any revolutionary or reformist movement. (Before Egypt can have a new government with full powers, the military believes there must be a referendum, two elections of three rounds each for a legislature, another referendum on a constitution, and then a presidential election. That doesn’t include runoffs and do-overs.)

Meanwhile there’s a debate underway about who “lost” the revolution, as if the demonstrators and liberal Egyptians could have gotten it right and changed Egypt over the last 12 months. Steven Cook partly blames the protesters for “narcissism” and “navel-gazing,” claiming they lost the opportunity to engage the public because they were too busy on Facebook and Twitter. Marc Lynch writes that the protesters have not captured the imagination of the wider public, though he (correctly) holds the SCAF responsible for bungling the transition so far.

Perhaps the most depressing read this week is a dark and self-critical essay by the revolutionary, blogger, and failed parliamentary candidate Mahmoud Salem, better known by his blog pseudonym Sandmonkey. He now believes that he and his fellow revolutionaries blew a chance to connect with Egyptians during the brief, hopeful moment after Mubarak quit; that, Salem argues, is when people were willing to change. Now that moment of possibility has evaporated.

One common thread runs through these writings, and through much of the critique of the uprising: that the revolutionaries never bothered to try to reach “the people.” There is some truth to that claim. Some of the most talented organizers among the original January 25 revolutionaries quickly turned their focus to party politics. Their efforts might bear fruit within one or two election cycles — five to ten years — but theirs is a dreary and inside job of crafting party platforms, opening branch offices, and recruiting staff and members. Another crucial cadre of revolutionaries were radical by conviction; it was by design, and not by accident, that they invested their energy in street protests and in forging links with labor activists, in order to spread the revolution into the workforce. That’s not to say that the remainder, who number at best a few thousand, didn’t try to engage the Egyptian public; they’ve been trying, but they haven’t been too successful. They go on television, they write newspaper columns, they hold press conferences. In August and September, they put on Revolutionary Youth Coalition road shows, where they went to towns and neighborhoods across Egypt to explain the goals of the protests. Even without a budget, however, they could have done that kind of outreach, in cafes and poor neighborhoods, every week since February 11; instead, much of their time was tied up in Tahrir protests whose utility made less and less sense even to sympathetic Egyptians.

The revolutionary youth alone hold promise for Egypt’s politics of accountability, rule of law, minority rights, and civilian control over the army — the unpopular but important bulwarks of a more liberal order. It would be a mistake to focus too much on public opinion of the protests, or even the gatherings’ size. What matters is their impact. The military, in fact, has set the parameters. Since February, they have scorned those who negotiate with them in good faith at polite meetings. The only concessions the generals have made — including, last month, their agreement to schedule presidential elections a year and a half earlier than they’d originally wanted — came as the result of violent protests in Tahrir Square. Perhaps the revolutionaries found it simple to flood Tahrir in response to every crisis; but it was the generals who taught them that protest was the only tool that actually worked.

So when it comes to blame, save it for the military, the actor driving events and the sole authority responsible for Egypt. The act, now ragged, has the generals pretending to be reluctant rulers, eager to hand over the keys if only a responsible captain would materialize to steer the ship of state. The rest of the players in Egypt merit mere disappointment: the mediocre politicians; the Muslim Brothers who repeatedly passed up the opportunity to take a moral, national position rather than defend their narrow institutional self-interest; the activists who failed to weave a national culture movement in the aftermath of January 25; the Egyptian elites who didn’t invest their money and influence in revolutionary causes; the civil servants and state institutions that slavishly serve whoever is in power; and Washington, which has utterly failed to persuade its billion-dollar welfare ward, the SCAF, to behave responsibly.

Is Egypt’s revolution dead, beguiled by its own hype, endlessly occupying and fighting over meaningless patches of pavement while the rest of the country forgets about their utopian aims? “Symbols are nice, but they don’t solve anything,” Mahmoud Salem writes. “There is a disconnect between the revolutionaries and the people. … Our priorities are a civilian government, the end of corruption, the reform of the police, judiciary, state media and the military, while their priorities are living in peace and putting food on the table.”