The Ramadan Moon, Lost in Haze

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

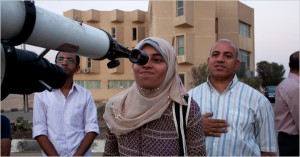

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

“It looks like trouble,” he said.

His deputy, Ahmed Fathy, concurred with a sigh, “I’m afraid we’re not going to see anything tonight.”

The two Egyptian physicists on Tuesday night had a delicate mission: They were charged with providing the scientific imprimatur to the start of the holiest time for Muslims worldwide, the lunar month of Ramadan. Egypt plays a major role in this ritual because it is the seat of Al Azhar, the world’s most prominent Sunni Muslim institution.

According to the Koran, Ramadan, a month of fasting and prayer, begins on the first night that the crescent moon is visible to the naked eye. For centuries, clerics and laymen jostled to spot the Ramadan moon first and often differed. An area with cloudy skies or a different longitude and latitude might declare Ramadan a day or even two later than the rest of the Islamic world.

Modern astronomy long ago took the mystery out of the lunar calendar, whose year lasts some 11 to 12 days less than the Gregorian year used by most non-Islamic countries.

Mr. Mahmoud, the president of Egypt’s National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, publishes a hefty book of tables that lists the precise time and location that the Ramadan moon will appear in various cities throughout the Islamic world.

But science, it seems, can go only so far.

“We know it’s there, but Shariah requires us to see it with our eyes,” Mr. Mahmoud explained. The grand mufti, Egypt’s highest religious authority, awaits a report from Mr. Mahmoud’s team and from a secondary group of spotters organized by the Egyptian National Survey Authority.