Now What?

In The Boston Globe I write about the competing schools of thought over what Egypt’s next government should look like. This debate will only get more complicated as the year wears on, with different philosophies vying for predominance on the surface, while powerful and silent vested interests struggle for power below.

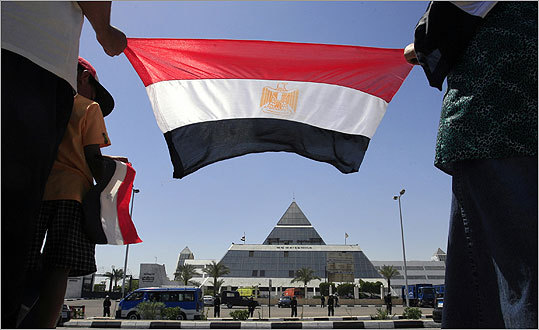

CAIRO — Traffic stopped in Tahrir Square during the revolution, but four months later, the torrent of marching humans that briefly made Cairo a world symbol of the thirst for justice has been replaced by the familiar, endless stream of grumbling cars.

The tricolor paint on the city’s trees, applied with gusto in the immediate weeks after President Hosni Mubarak resigned, has already begun to fade. As the wilting heat approaches its summertime averages in the 90s, vendors here do a brisk business selling “I [heart] Egypt” T-shirts, mock license plates commemorating the date of the uprising, and posters of the young martyrs to Mubarak’s security forces.

Schools have reopened; births and deaths are once again registered by Egypt’s ubiquitous bureaucracy; and the machinery of state continues to deliver the basic services that make this nation of 80 million function. The military junta that replaced Mubarak polices the streets and censors the media, though with a touch slightly lighter than Mubarak’s. There are still street demonstrations; on most Fridays, small factions chant in Tahrir Square and distribute leaflets demanding to put figures of the old regime on trial, fix the broken economy, or allow greater freedom to criticize the government.

Most of the nation’s energy, however, has shifted to a new debate: what should come next. Egyptians are realizing that they now face a challenge perhaps even more historic than its revolution. They need to design, nearly from scratch, a legitimate state to govern the most populous Arab nation in the world.

Egyptians are supposed to write a new constitution sometime this fall. And although no one is sure precisely how this will occur — the schedule is controlled by the military junta, which communicates chiefly through updates on its Facebook page — the public conversation has already metamorphosed into raging debate over what the government should look like. The outpouring of public frustration that reached a crescendo in Tahrir Square on Feb. 11 has now moved onto a crowded lineup of television talk shows and the cafes. As youth activist Ahmed Maher put it over a demitasse at the Coffee Bean this week: “Before the revolution, everyone talked about soccer and drugs. Now they talk only about politics.”