Is Anyone Ready to Actually Lead Egypt?

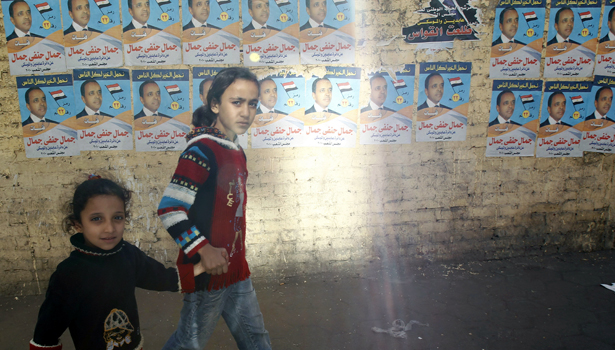

Girls walk past Muslim Brotherhood campaign posters in Cairo. (Reuters)

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

The Muslim Brotherhood is inflexible and exclusive, the military power-hungry and self-interested, liberals are in disarray, and a country that badly needs cooperation is once again plagued by division.

CAIRO, Egypt — The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi appears to have won Egypt’s first contested presidential election in history, a mind-boggling reversal for the underground Islamist organization whose leaders are more familiar with the inside of prisons than parliament. Whether or not Morsi is certified as the winner on Thursday — and there is every possibility that loose-cannon judges will award the race to Mubarak’s man, retired General Ahmed Shafiq — the struggle has clearly moved into a new phase that pits political forces against a military determined to remain above the government.

The ultimate battle, between revolution and revanchism, will remain the same whether Morsi or Shafiq is the next president. It’s going to be a mismatched struggle, one that will require unity of purpose, organization, and the sort of political muscle-flexing that has escaped civilian politicians for the entire 18-month transition process. If they can’t marshal a strong front on behalf of a unified agenda, they are likely to fail to wrestle the most important powers out of the military’s stranglehold.

After a year and a half in direct control, Egypt’s ruling council of generals (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF) appears to have grown fond of its power. As the presidential vote was being counted, SCAF issued a new temporary constitution that gives it almost unlimited powers, far greater than those of the president. It can effectively veto the process of drafting the new permanent constitution, and it retains the power to declare war.

“We want a little more trust in us,” a SCAF general said in a surreal press conference on Monday. “Stop all the criticisms that we are a state within a state. Please. Stop.”

In fact, all the military’s moves, right up to the last-minute dissolution of parliament and the 11th-hour publication of its extended, near-supreme powers, give Egyptians every reason to distrust it. Sadly, the alternatives are not much more reassuring.

Shafiq, the old regime’s choice, mobilized the former ruling party with an unapologetic, fear-driven campaign, drumming up terror of an Islamic reign while promising a full restoration to Mubarak’s machine. If he ends up in the presidential palace, he could place the secular revolutionaries and the Muslim Brotherhood in harmony for the first time since the early days of Tahrir Square.

Morsi, meanwhile, is known as an organization enforcer, not as a gifted politician or negotiator — which are the skills most in need as Egypt embarks on its high-risk struggle to push aside a military dictatorship determined to remain the power behind the throne.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate has few assets in his corner. He represents the single best-organized opposition group but doesn’t control it. Revolutionary and liberal forces are in disarray. Mistrust, even hatred, of the Muslim Brotherhood has flared among groups that should be the Brotherhood’s natural allies against the SCAF. And the Brotherhood itself has wavered between cutting deals with the military and confronting it when the military changes the terms. Many secular liberals say they relish the idea of the dictatorial military and the authoritarian Islamists fighting each other to exhaustion.

All this division promises a chaotic and difficult transition for Egypt after 18 months of direct military rule. If officials honor the apparent results (an open question, since the elections authority is run by SCAF cronies), Morsi will head an emasculated, civilian power center in the government that will have little more than moral suasion and the bully pulpit with which to face down the SCAF.

While the military’s legal coup overshadows the election results, it doesn’t render them meaningless. The presidency carries enormous authority; managed successfully, it’s the one institution that could begin to counter and undo the military’s evisceration of law and political life.

The example of parliament is instructive. Some observers said from the beginning that a parliament under SCAF would have no real power. But that didn’t turn out to be the problem with the Islamist-controlled parliament. It had symbolic power, and it could pass laws even if the SCAF then vetoed them. What made the parliament a failure was its actual record. It didn’t pass any inspiring or imaginative laws, it repeatedly squashed pluralism within its ranks, and it regularly did SCAF’s bidding. That’s what discredited the Brotherhood and its Salafi allies and led to their dramatic, nearly 20 percent drop in popularity between the parliamentary elections and the first round of presidential balloting five months later.

It would be greatly satisfying if the corrupt, arrogant, and authoritarian machine of the old ruling party were turned back, despite what appears to have been hints of an old-fashioned vote-buying campaign and a slick fear-mongering media push, backed by state newspapers and television. On election day, landowners in Sharqiya province told me the Shafiq campaign was offering 50 Egyptian pounds, or about $8.60, per vote.

But it would be greatly unsatisfying for that victory to come in the form of a stiff and reactionary Muslim Brotherhood leader who appears constitutionally averse to coalition-building and whose political instincts seem narrowly partisan, at a time when Egypt’s political class is locked in death-match with the nation’s military dictators.

Egypt’s second transition could last, based on the current political calendar, anywhere from six months to four years. A new constitution will have to be written and approved, likely with heavy meddling from the military and with profound differences of philosophy separating the Islamist and secular political forces charged with drafting it. A new parliament will have to be elected. And then, possibly, the military (or secular liberals) could force another presidential election to give the transitional government a more permanent footing.

Meanwhile, during this turbulent period, Egypt will have to contend with the forces unleashed during the recent, bruising electoral fights.

Shafiq’s campaign brought into the open the sizable constituency of old regime supporters (maybe a fifth of the electorate, based on how they did in recent votes) and Christians terrified that their second-class status will be grossly eroded under Islamist rule.

Liberals will have to explain and atone for their stands on the election. Many of them said they would prefer the “clarity” of a Shafiq victory to a triumphalist Islamic regime under Morsi, and cheered when parliament was dissolved — appearing hypocritical, expedient, and excessively tolerant of military caprice.

The Brotherhood still hasn’t made a genuine-seeming effort to placate and include other revolutionaries, spurning entreaties to form a more inclusive coalition. It attempted, twice, to force through a constitution-writing assembly under its absolute control. Yet, once more, the Brotherhood has a chance to save itself. So far, at each such juncture it has chosen to pursue narrow organizational goals rather than a national agenda. It would be great for Egypt if the Brotherhood now learned from its mistakes, but precedent doesn’t suggest optimism.

Partisans of both presidential candidates told me they expected a big pay-off when their man won: cheaper fertilizer, free seeds, a flood of affordable housing, jobs for all their kids, better schools. None of these things is to be expected in the near future under any regime in Egypt. Disappointment is sure to proliferate as everyone realizes how difficult Egypt’s long slog will be.

There’s much hand wringing among Egyptians about the last-minute power grab by the military through the sweeping constitutional declaration it published on Sunday. In a land of made-up law and real power, why the obsession with power-mad generals, co-opted judges, and the arbitrary declarations they publish? SCAF’s decisions only matter because of its raw power, tied to the gunmen it has deployed on the streets and its willingness to use them against unarmed civilians. This inequity will only change with a shift in actual power, not because of a clever and just redrafting of laws. An elected president, or a defenestrated parliament for that matter, could issue its own, better constitution and declare it the law of the land, and enter a starting contest with SCAF. Authority belongs to whomever claims it and can make it stick.