Putin’s crushing strategy in Syria

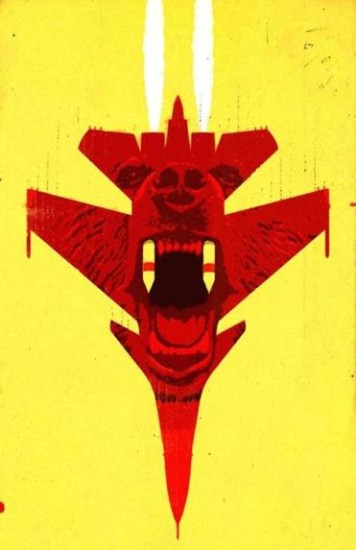

Illustration: RICHARD MIA FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

LATAKIA, SYRIA

WHEN RUSSIAN JETS started bombing Syrian insurgents, it was no surprise that fans of President Bashar Assad felt buoyed. What was surprising was the outsized, even over-the-top expectations placed on Russian help.

“They’re not like the Americans,” explained a Syrian government official responsible for escorting journalists around the coastal city of Latakia. “When they get involved, they do it all the way.”

Naturally, tired supporters of the Assad regime are susceptible to any optimistic thread they can cling to after five years of a war that the government was decisively losing when the Russians unveiled a major military intervention in October.

Russian fever isn’t entirely driven by hope and ignorance. Many of the Syrians cheering the Russian intervention know Moscow well.

A fluent Russian speaker, the bureaucrat in Latakia had spent nearly a decade in Moscow studying and working. Much of Syria’s military and Ba’ath Party elite trained in Moscow, steeped in Soviet-era military and political doctrine, along with an unapologetic culture of tough-talking secular nationalism (there’s also a shared affinity for vodka or other spirits).

The Russians have announced that they will partner with the French to fight the Islamic State in the wake of the terrorist attacks in Paris. But beyond new friendships forged in the wake of the Paris massacre and the downing of a Russian charter flight over the Sinai in October, Moscow’s strategic interest in Syria is longstanding and vital to its interest.

The world reaction to the Russian offensive in Syria has been as much about perception as military reality. Putin, according to Russian analysts who carefully study his policy, wants more than anything else to reassert Russia’s role as a high-stakes player in the international system.

Sure, they say, he wants to reduce the heat from his invasion of Ukraine, and he wants to keep a loyal client in place in Syria, but most of all, he wants Russia’s Great Power role back.

For all the mythmaking and propaganda, there is a powerful historical context to Russia’s latest foreign military intervention. Like all states that try to project force beyond their borders, Putin’s Russia faces limits. But those limits differ markedly from those that doomed America’s recent fiascoes in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The spectacular international attacks by Islamic State militants against targets in the Sinai, Beirut, and Paris have reminded Western powers of the other interests at stake beyond a resurgent Russia and a prickly Iran. Until now, Russia’s new role in Syria has stymied the West, impinging on its air campaign against ISIS and all but eliminating the possibility of an anti-Assad no-fly zone.

Russia’s blitzkrieg in Syria might have only tilted the conflict in Assad’s favor, with no prospect of securing an outright win for the dictator in Damascus — and yet, that might be more than enough to achieve Russia’s limited objectives.

As a result of a bold, arguably cynical, gamble, Putin might just get what he wants.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER WORLD WAR II, the Soviet Union quashed armed insurgencies in many of its newly annexed republics, including Western Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Western Belarus.

Those early campaigns shaped a distinct Soviet approach to counterinsurgency, according to Mark Kramer, program director of the Project on Cold War Studies at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

The United States was at the same time developing its own theories about winning over local populations, which underpinned the doctrine of “population-centric” counterinsurgency that ultimately failed to accomplish American aims in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s.

The Soviet Union, on the other hand, developed what Kramer calls “enemy-centric” counterinsurgency: Kill the enemy, establish control, and only then sort out questions about governance and legitimacy.

Harsh tactics worked for the Soviets. Kramer quotes the future Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev directing his agents in 1945 Ukraine to use unbridled violence against insurrectionists: “The people will know: For one of ours, we will take out a hundred of theirs! You must make your enemies fear you, and your friends respect you.”

In 1956, the Soviets used similar tactics to crush an uprising in Hungary. Despite the widespread perception of failure in Afghanistan, says Kramer, the Soviets had successfully propped up their local client, at great but sustainable cost, until Mikhail Gorbachev decided to repudiate the war there — just before US antiaircraft missiles arrived in the theater.

Vladimir Putin, insulated from political pressure, has drawn on this history to craft a brutal approach to counterinsurgency.

The first post-Soviet president, Boris Yeltsin, presided over the weakening of the Russian military and a desultory defeat at the hands of rebels in the first Chechen war of 1994 to 1996. As Putin prepared for a second Chechen war, in 1999, he used political coercion to guarantee friendly media coverage from Russian television and erase any meaningful political dissent over the war.

“During Putin’s [first] presidency, the Russian government was able to quell the insurgency in Chechnya without, in any way, having ‘won hearts and minds,’ ” Kramer wrote in a 2007 assessment after the Chechen war was provisionally settled in Putin’s favor. “Historically, governments have often been successful in using ruthless violence to crush large and determined insurgencies, at least if the rulers’ time horizons are focused on the short to medium term.”

Kramer compares Putin’s approach to that of Saddam Hussein, Stalin, and Hitler. It also seems very similar to Bashar Assad’s strategy today in Syria.

With no need to worry about public opinion, Putin’s counterinsurgency could kill countless Chechen civilians. When retaliatory Chechen terrorist attacks killed hundreds of Russian civilians in theaters and schools, Putin’s campaign only gained support. Russia’s flawed strategy in Chechnya ultimately created an outcome that worked for Putin.

“Historically, insurgencies tend to last eight to ten years, and most of the time Soviet and Russian forces have achieved their goals,” Kramer said.

Today Russia can’t entirely ignore international opinion, which has run strongly against its intervention in Ukraine. Doubling down in Syria, it turns out, has created the possibility of an exit strategy.

“Putin’s trying to change the topic from Ukraine, and maybe he’s been successful on that,” said Thomas de Waal, a scholar at Carnegie Europe who wrote a book about the Chechen war and closely follows Russian policy.

The style that Russia has honed — “overwhelming force as your basic strategy,” de Waal said — fits well with Assad’s merciless shelling of opposition areas. “You treat every enemy city as Berlin, and you pulverize it,” de Waal said, describing Putin’s approach to insurgencies. “There’s no subtlety, no regard for collateral damage or civilians.”

STATE MEDIA IN SYRIA has continued to herald the Russian intervention as a massive game-changer, but on-the-ground realities have already brought short initial expectations. Early predictions of a rout foundered when the Russians encountered resistance.

Anti-Assad forces, as any longtime observer of the conflict would have predicted, continue to fight back hard. Local militants defending their communities rarely quit; when they are defeated, victory can require months or years of fighting. In response to Russia’s escalation, the United States and other foreign backers of anti-Assad militias opened the spigot of aid including antitank missiles. Jihadists are equally formidable foes.

Assad appeared to be on the losing end of a stalemate before the Russian intervention. A major coordinated push by Russia, Iran, and the Syrian government could turn the momentum the other way, but analysts of the conflict doubt there’s any prospect of an outright victory.

Once the dust settles, the Syrian government will still suffer from the same manpower shortage that has plagued its efforts, and antigovernment forces will remain entrenched, said Noah Bonsey, Syria analyst for International Crisis Group. With Russian help, the government has gained ground around Aleppo but has lost some around Hama.

“In real military terms, it gets us right about to where we were before the intervention,” Bonsey said. “We haven’t seen any significant breakthroughs.”

Some of the closest followers of the Kremlin’s designs in Syria and the wider Middle East, like Russian analyst Nikolay Kozhanov, argue that Putin was never aiming for a military solution in Syria but only to better position Russia in the diplomatic great game.

Another Russian analyst, Nadia Arbatova, a political scientist at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations, said Russia wants to regain influence by convincing the United States and other Western powers to join Moscow in a counterterrorism alliance. She doesn’t think the Kremlin has carefully studied its own history in foreign interventions. The Syrian intervention, in her view, is less about Syria than it is about showing the West that Moscow can project global power again.

“For the first time after the collapse of the USSR, Russia is conducting a big military operation outside the post-Soviet space,” Arbatova said. “Hence Russia is not just a regional center but a world power.”

The most important lesson from Russia’s counterinsurgency history might be its Machiavellian reading of the politics involved. Moscow, when it succeeds, lays out clear aims and then methodically deploys force and political tools to reach them.

In Syria, Russia has sided with a rigid regime that has demonstrated a rigid unwillingness to entertain any compromise at all with an uprising that has engulfed most of the country. Its main partner is the Islamic Republic of Iran, whose political culture, regional interests, and long-term goals differ greatly from Moscow’s.

Putin might find his Syrian adventure meets even more obstacles than his increasingly bold interventions in Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine. Although each of Putin’s previous interventions carried an increasingly costly international price tag, all of them came in the former Soviet space, in an arena where no outside power can freely maneuver.

Syria is a different story altogether, a civil war saturated with foreign proxies. Russia is intervening on behalf of a minority regime that has already been fighting at maximum capacity. On the other side is a fractured rebellion, trapped between government forces and the Islamic State — which despite its considerable failings and only tepid backing from the United States has managed to keep Damascus on the defensive.

In government-controlled areas, Assad supporters have fully swallowed the enthusiastic propaganda about the intervention, peddled by Moscow and Damascus both.

“It won’t be long now, it’s going to finish soon,” said one volunteer fighter for the Syrian regime, a 38-year-old militiamen in the National Defense Forces with the word “love” tattooed on his forearm, sipping juice at a seaside café near his base. By next summer, he predicted, the war would be over, thanks to Moscow. “There will be strong forces of Russians, Iraqis, and Syrians fighting together. We will be strong. We are at end of the crisis.”

History suggests a more pessimistic forecast. Russia might get lucky, winning a diplomatic settlement at an instant when the Islamic State’s attacks have prompted a confluence of interests. More likely, however, Moscow will settle in for a decade of crushing counterinsurgency in Syria, against foes with considerable legitimacy, who represent a possible majority of Syrians and have the backing of some of the world’s richest and most powerful states. Russia has the resources and security to wait and see how the long game plays out, but it’s unlikely to end with either the blitzkrieg for which Assad’s fighters yearn or the hasty and favorable political settlement that Putin’s diplomats are pushing.