How people got used to Moqtada al-Sadr

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

MOQTADA AL-SADR HAS been Iraq’s most recognizable villain since 2003, when he burst onto the scene as the most potent challenger to the US military occupation of Iraq. His rivals painted Sadr as a thug and an amateur, a wannabe who was lucky enough to be a member of a vaunted clerical dynasty yet nevertheless struggled to hold onto its followers.

A surprising thing has happened in the years since. After a series of violent clashes and reversals, Sadr has refashioned himself as Iraq’s premier nationalist statesman. Despite a very recent historical reputation as a corrupt sectarian warlord, Sadr today has emerged as Iraq’s standard bearer for secularism and reform. Running on an anti-corruption platform, he edged out all others to finish first in Iraq’s national elections earlier this month.

The United States, who had such trouble with Sadr from 2003 to 2008, might be expected to flinch at his embrace of the Iraqi Communist Party, and his growing political influence. Remarkably, though, US officials have stayed quiet about pivotal role Sadr now plays.

His steady expansion of power over 15 years is a sign of the importance of charisma, staying power and, most importantly, improvisation in a volatile and sharply divided region. Sadr’s case illustrates how a leader benefits from being a known quantity personally, while at the same time bending and shifting his ideology and political to accommodate the political winds.

A decade ago, the young Shiite cleric was fulminating against the Americans and the Iraqi “puppets” they had installed in Baghdad. He often wore a white shroud symbolizing martyrdom as he delivered thunderous Friday sermons. His Shiite militant followers were known for nighttime murders of Sunnis. He set out purist dictates against Western-style hedonism, prompting attacks against gays and liquor stores.

Today, he welcomes not just the communists but also the same secular Iraqis his organization used to target. Sadr’s communications team tweets out his latest edicts, which are more likely to contain anodyne pronouncements about political coalition building rather than fire-and-brimstone warnings against American meddling.

He solidified his power in the years after the US invasion through his fearsome Mahdi Army militia, and through jobs and spoils he acquired through the control of key government positions, including the lucrative health ministry. Yet during the recent election campaign, he vowed to overturn Iraq’s spoils system, which allows sectarian movements to carve out fiefdoms and pillage the state’s coffers.

When seeking to predict events in a country such as Iraq, policy experts in the United States and elsewhere routinely focus on deep-seated rifts around ethnicity, ideology, and religious doctrine. What’s easy to underestimate is the role of a troubled nation’s day-to-day domestic political environment — and the skill with which some key leaders navigate it.

Iraq’s domestic politics remain deadlier than those of most other countries, but the system there, as in so many places, rewards politicians who can read the crowd, who channel its frustration with self-dealing elites, and who avoid getting boxed in by their own past.

Sadr is now the single most powerful leader in Iraq, and he brings a more clear platform and set of ambitious national goals to the table than any other political leader. As kingmaker in the complex negotiations to form the next government, he is now in a position to set the government’s agenda with his unlikely — but politically savvy — platform of reform and secular nationalism.

* * *

Sadr’s father and uncle were revered grand ayatollahs whose teachings guided the behavior of millions of followers and inspired a generation of Shiite Islamist activists. His father was murdered by Saddam Hussein in 1999, and his fourth son, Moqtada, was considered too young and inexperienced to pose a threat. His Iraqi critics dismissed him as “Ayatollah Atari” — a reference to his love of video games and supposed lack of intellect.

He turned 30 the same year that the United States toppled Saddam and occupied Iraq. Within days of the invasion, Sadr had mobilized legions of followers. The one rival who could have challenged Sadr for leadership of Iraq’s Shiite poor and dispossessed was Abdel Majid al Khoei, an older and far more senior cleric who had fled into exile in London after helping lead an uprising against Saddam Hussein in 1991.

Al Khoei returned to Iraq in April 2003, with the blessing of Western troops, and set up operations in Najaf. Within weeks, he was murdered by a frenzied mob. His family, along with US officials, say that the killing was not spontaneous, but was carefully orchestrated by Sadr. Sadr denied the accusation and no one has ever been charged for Al Khoei’s killing.

Sadr quickly established himself as an uncontainable force in Iraq. Almost the entire Shiite establishment cooperated with the US occupation, viewing it as the quickest route to an electoral democracy that would bring power to the Shiite majority. The leading clerics in Najaf endorsed elections under America’s auspices. Opposition militias opened political offices and worked with the occupation authority.

Only Moqtada al-Sadr confronted the Americans from the beginning. He led demonstrations and recruited a militia. The Americans considered him dangerous and mercurial. Some Iraqis considered him a spoiler, creating unnecessary risks and detours along a sure path to electoral democracy.

Within a year of Saddam’s ouster, Sadr’s Mahdi Army was fighting an armed rebellion against the American military in central Iraq and the British in the south. Tellingly, Sadr already then couched his rebellion in nationalist terms. He sent reinforcements to the Sunni insurgency in Fallujah, in an effort to craft a trans-sectarian front.

In the seven years that followed, Sadr’s militia starred in some of the worst episodes of violence. They led the charge in the sectarian bloodletting that climaxed in 2006. They declared war against the central government in Baghdad, and were crushed. His political wing won a sizeable bloc in parliament and ran the health sector, winning a reputation for graft, corruption, and poor service.

Sadr retreated into exile in Iran from 2008 to 2011, where he studied with a senior cleric to try to raise his status. He shuttered his militia, and kept a low profile.

By the time he returned, the United States was pulling out its last combat troops from Iraq, and Sadr began his turn toward nationalism and reform.

Unlike other Iraqi leaders, his core following remained devoted to him personally, so he could count on consistent populist support, and votes. And Sadr displayed a willingness to adapt and change. He disavowed the extremist sectarians from his movement, many of whom left to form other militias and parties. He also heaped criticism on Iran for its meddling and mismanagement of Iraq’s interests. He fired and publicly lambasted some of the politicians in his movement who had been found guilty of corruption. And when the Islamic State surged through Iraq, he reestablished his militia (now called the Saraya Salam, or “Peace Brigades”), and joined the ultimately successful struggle to reimpose Baghdad’s authority across the country.

* * *

BY 2015, A GRAY-HAIRED and more muted Sadr had carved out a niche for himself as an anti-sectarian Shiite committed to a functional Iraqi state. That summer, protests broke out across Iraq against the government’s epic failures to provide security, jobs and even basic services like electricity. Sadr shrewdly reached out to the communists and secular reform activists leading the protests. He sent emissaries to Sunnis who felt disenfranchised from the state.

Out of those early meetings an enduring alliance took shape. He took aboard the suggestions of the seasoned reform activists, and decided that what Iraq needed most of all was fresh faces: qualified, independent professionals who could run its eroding government. The housecleaning began inside his own movement. Sadr stunned his parliamentary delegation, telling them he wouldn’t allow any of them to stand for reelection. His successful slate of candidates this year consisted entirely of “technocrats,” people with managerial experience but not any disqualifying political history. Some of Sadr’s own lieutenants questioned the move, arguing that political connections and party backing are crucial for getting things done in Iraq’s fractious and corrupt government, but Sadr was adamant.

He visited Saudi Arabia and endorsed warmer relations between Baghdad and Riyadh, vowing to balance Iraq’s position among the foreign powers with a hand in its politics and security.

There’s a certain Nixon-goes-to-China element to Sadr’s turn to secularism. Only a seasoned militant with impeccable sectarian credentials can make a turn toward pluralistic nationalism. His positions today are all the more plausible because nationalism has been a consistent thread in all his ventures since 2003 — and because he remains a secretive, illiberal leader with untrammeled authority within his own movement. His millions of followers bring him almost exactly the same number of votes during every election. His consistent promise is to seek more jobs and a bigger share of Iraq’s economic pie.

Naturally, there’s plenty of reason not to trust the cleric’s transformation. Sadr is a savvy operator, a seasoned opportunist who has shifted position over and over. He might do so again. And his alliance with the secular reformers and the Iraqi Communist Party could collapse if the next Iraqi government is formed with Sadr’s reformist blessing but still is unable to deliver better results than its predecessors.

In his new incarnation as an aging statesman, Sadr hasn’t shifted all that much. His followers have stopped the vigilante attacks against gays and liquor stores, but they haven’t endorsed social freedoms and rights, either.

In private, diplomats say they don’t expect Sadr to act as a provocateur. His rhetoric can be heated, but he’s a pragmatic politician who regularly meets with Western ambassadors.

Despite his clerical background, Sadr’s goals line up with a strange array of otherwise unlikely allies: secular Iraqi reformists, liberals, Sunnis, militants who want to integrate into the Iraqi state, even some Western governments. Sadr wants a strong government in Baghdad, which makes room for Iraqis of every sectarian, ethnic and political stripe. He also argues that Iraq’s top political jobs cannot be distributed on a sectarian basis, as in Lebanon.

Since 2003, there hasn’t been any parliamentary opposition in any of Iraq’s governments — every single party that has won votes has preferred a position in government so it can extract its share of corruption.

The test for every reformist movement is what happens when it gains significant control over the state. Fulminating against the corruption of past leaders is easy; it’s far harder to resist the temptation to take advantage when your side is in power.

Iraq’s system is so deeply distorted that only a strong jolt can change it. Sadr benefits from longevity, low expectations, and the lack of any more attractive alternative. But sometimes that’s enough.

Can a Shiite Cleric Pull Iraq Out of the Sectarian Trap?

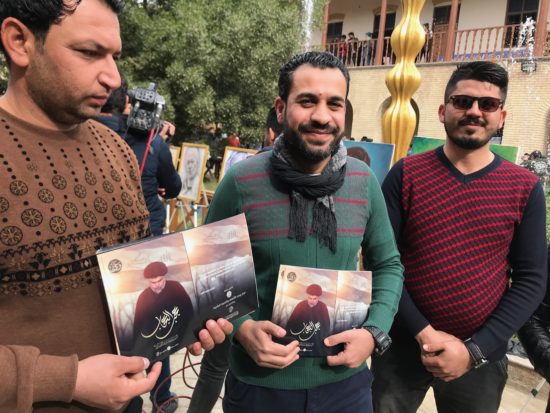

The Shiite cleric Moktada al-Sadr at a demonstration in April against the bombings of Syria by Britain, France and the United States. CreditHaidar Hamdani/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

[Published in The New York Times.]

May 11, 2018

BAGHDAD, Iraq — Iraq’s parliamentary elections on May 12 might seem to offer more of the same because most of the leading candidates and movements have dominated the country’s political life since the United States unseated Saddam Hussein in 2003. But the 44-year-old firebrand Shiite cleric Moktada al-Sadr is leading an encouraging transformation, which could jar Iraq’s politicians out of their sectarian rut.

Mr. Sadr inherited millions of devoted followers from his family of revered religious scholars. Both his father and father-in-law were grand ayatollahs, the highest clerical level of Shiite Islam. He cemented his status by leading a bloody resistance against the American occupation and fighting the United States-allied government in Baghdad. He stubbornly defied foreign intervention, angering both Iran and the United States. He has purged corrupt operatives from his movement.

In the summer of 2015, Mr. Sadr made a potentially historic about-face, uniting with the Iraqi Communist Party and secular civil society groups who were protesting the government’s failure to provide security against the Islamic State or even the basic necessities of life, including jobs and electricity. Together, the new alliance demanded an end to corruption.

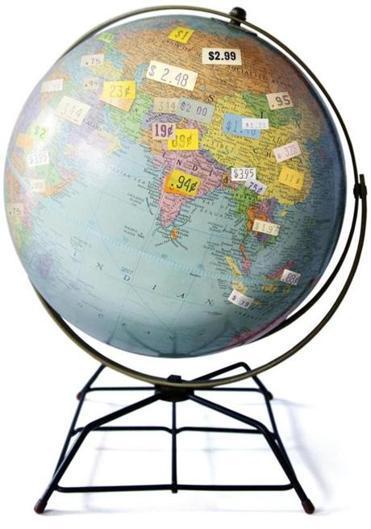

Iraq regularly tops world rankings for corruption and suffers endemic unemployment, which is particularly high among youth. When oil prices were high, alleged corruption reached an epic scale, but the people did not receive any benefits in infrastructure, jobs or services. Even vital security services were gutted by no-show jobs, as glaringly revealed when there was no army on hand to stop the Islamic State’s sweep through Mosul and Anbar Province to the gates of Baghdad.T

Corruption has kept Iraqis poor and almost left the country at the mercy of the Islamic State. That is why Mr. Sadr’s slogan “Corruption Is Terrorism” resonates with so many Iraqis. Frustrated with a decade of failures by the rulers in Baghdad, Mr. Sadr embraced civil society groups and their agenda: civic rights, better governance, fair distribution of resources.

An important outcome of Mr. Sadr joining a nonsectarian coalition is a new strain of pluralism and tolerance. The liberating effect is visible in how Iraqis irrespective of class, sectarian and sexual identities can reclaim public spaces without fear.

One spring morning, a group of young men in bouffant hairdos and burgundy and bright green three-piece suits hung out in Qishleh Gardens near Mutanabi Street, the historic gathering place of Baghdad’s poets and intellectuals. In the local context, their attire announced them as gay men. As the men in colorful suits walked around, the clerics recruiting fighters for the Shiite Islamist militias nearby didn’t even throw them a sideways glance.

In the afternoon, some of the men in colorful suits joined an anti-corruption demonstration led by supporters of Mr. Sadr. “We all want to put an end to corruption,” said Mohamed Ismail, a 26-year-old unemployed day laborer. “We are all together.”

Three years earlier, when demagogues loyal to Mr. Sadr were exhorting vigilante attacks on men seen as gay, the pairing would have been unthinkable. Back then, Iraq was riven by difference — the sectarian-hued struggle between the Islamic State, which purported to speak for the Sunnis, and the governments led by Shiite Islamists, who claimed to represent the Shiite majority that had been oppressed under Mr. Saddam.

At the Baghdad Cultural Center, adjacent to the Qishleh Gardens, smiling volunteers from Mr. Sadr’s organization distributed fliers with his pronouncements. “Our new goal is to start an independent technocratic government,” said Majid Hamid, a 26-year-old volunteer. “We have no problem with anyone who is Iraqi.” The movement’s emphasis is now on civic questions.

After more than a decade of dominance by Islamist Shiite movements, competitors for power can no longer meaningfully distinguish themselves by their sectarian identity. Self-styled religious parties have been implicated in every major graft scandal, including the mishandling of oil revenue and defense contracts.

In early May, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the most revered cleric in the country, took the unprecedented step of declaring that true believers must not vote along sectarian lines and reminded voters that the clergy has not endorsed any party.

The biggest transformation of all has come during the fight against the Islamic State, which united all manner of Iraqis against nihilist fundamentalists: Shiite and Sunni, Kurd and Arab, Muslim and Christian, religious and secular. Every major electoral faction includes a mix of Iraqis, and the ideas of nationalism and secularism are slowly returning to the Iraqi political sphere.

Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who has roots in the secretive Shiite Islamist Dawa Party, has positioned himself as a nation-builder who thwarted challenges from Sunni supremacists and Kurdish separatists but is willing to accept any patriot as a member of his coalition. Even the most militant Shiite militias have included Sunni partners in their electoral coalitions, including the Fatah Alliance, led by Iran’s fearsome ally, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.

Mr. Sadr has ordered his followers to support the idea of a secular, nationalist government run by “technocrats,” experts who are not career politicians and supposedly will be able to solve Iraq’s ills. He touts the importance of the rule of law and civilian power.

In a series of interviews with politicians, analysts, fighters and citizens, I repeatedly heard that a broad range of Iraqis believe they are at the beginning of a “nationalist moment,” when the country’s political culture might be transformed for the better.

Mr. Sadr has reinvented himself countless times in an erratic political career and can be a fair-weather ally. His appreciation for new, secular allies is not an endorsement of liberalism or progressive views.

But Mr. Sadr has always been a nationalist, committed at least in rhetoric to unifying patriotic Iraqis regardless of sect or ethnicity. His current campaign for a civil, anti-sectarian, reformist government raises hopes and possibilities not experienced in recent Iraqi history. He is changing the terms of political debate.

His political lieutenants say they want to lead the Iraqi government, or else serve as a vigilant parliamentary opposition. Since 2003, every faction that won a share of votes opted to join a broad coalition government and extract its share of the spoils from the public sector trough.

Mr. Sadr shows that a political movement known for the exploits of its militia and corruption can also become a standard-bearer for root-and-branch political reform. His unlikely reformist alliance could give Iraq’s political culture the jolt it needs.

Thanassis Cambanis, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author, most recently, of “Once Upon a Revolution: An Egyptian Story.”

Can Militant Cleric Moqtada al-Sadr Reform Iraq?

[Read the full report at The Century Foundation.]

In the fifteen years since the American invasion toppled Saddam Hussein from power, Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr has distinguished himself from other emerging Iraqi leaders with his endurance, iconoclasm, and unpredictability. He has cut a bedeviling and at times magnetic figure in his country, and he is one of the few sectarian leaders whose popularity has crossed sectarian lines.

Through war, flips of allegiances, involvement in corruption, and military victory and defeat, Sadr has managed to preserve his maverick image as a stubbornly independent man deeply committed to his principles, even as those principles shift over time. Now, with the May 12 Iraqi elections approaching, he is trying to parlay his reputation as a nationalist free-thinker into a movement that can transform Iraq’s political system.

In fact, Sadr has fashioned himself into an unlikely tribune of reform in Iraq. A persistent thorn in the side of foreign powers and Iraqi politicians alike, the graying forty-four-year-old is now trying to radically reshape his country’s politics. He has freshly renounced religious sectarianism, building an alliancewith Communists and secular reform activists.1 He has attacked Iraq’s corrupt spoils system, with slogans such as “corruption is terrorism” that resonate with millions of disenchanted Iraqis. His unorthodox electoral campaign joins Shia partisans, Communist ideologues and some of Baghdad’s secular elite. Sadr’s popularity, hard power, and unifying message make him a direct threat to Iraq’s political class.

Even though his movement is unlikely to win a majority, Sadr’s unique campaign and nationalist-religious-secular alliance has upended nostrums about Iraqi and Middle Eastern politics. He hopes to establish new guiding principles: Sectarian movements can change their politics and become secular and nationalist. Armed militants can take part in electoral politics and government. Sectarian constituencies can embrace nonsectarian principles and support power-sharing and coexistence.

The evolution of Sadr and his movement has unfolded along pragmatic lines, with many flaws and inconsistencies. Nonetheless, Sadr’s political makeover amounts to a groundbreaking and encouraging transformation. It compels other established movements in Iraq to address the core challenges of security and governance, while building trans-sectarian or nationalist coalitions. He sets an example for other leaders and political organizations interested in exiting the confining boxes of sectarianism and patronage and mobilizing broader, more fluid and inclusive idea- or policy-based movements.

The success of Sadr’s approach and platform is more important than that of his candidates. If his coalition is repudiated by voters, or abandons its plans to challenge poor governance, then we can expect more of the dispiriting business-as-usual from Baghdad. But if Sadr follows through after the election and promotes the formation of a platform-based government with a legislative opposition, then we can expect Iraqi politics to enter a new phase, moving away from narrow sectarianism and patronage-only politics. A transition to a government with some technocrat ministers, a real opposition, and some pretense of nonsectarianism is necessary if Iraq is to begin addressing policy problems that affect the stability of the entire Middle East. The most pressing concerns include securing and developing the areas liberated from the Islamic State and reincorporating Sunni Arabs and Kurds into Baghdad’s fold.

This report traces Sadr’s evolution, and both the perils and promises of the road ahead. It is based on more than forty interviews conducted in Iraq in February and March 2018, with support from a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Charismatic Provocateur

Iraqis have long bemoaned a lack of leadership and vision within the ruling class. The melee of corruption and militia-formation that has plagued Iraqi public life since 2003 has featured a parade of politicians and warlords, many of whom have evolved into effective operators. Yet only two indisputably strong, charismatic leaders have distinguished themselves from the fragmentary society of party bosses, warlords, tribal leaders, and the grifters and opportunists who have made deals with the wardens of cash. Those two are both Shia clerics, and no love is lost between them.

The first, and most influential, is Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the single most authoritative leader in Iraq. A cleric of impressive intellect and conservative (rather than radical) nationalist views, Sistani is credited as a moderating force who at times kept Iraq from civil war and at others helped mitigate the scope and damage of sectarian conflict.

The other enduringly powerful figure is the far more junior Sadr, who in the wake of the U.S. invasion emerged as a strong counterpoint to Sistani’s style of leadership and modest ambitions. Sadr lacks the educational pedigree of the ayatollahs who are considered “marjaiya,” or sources of emulation, and whose teachings are followed by millions worldwide. Still, Sadr inherited the millions of passionate followers of his father and uncle, both revered ayatollahs; and he also continued the family feud against Sistani, whom the Sadrs regarded as too timid.

Sadr was not yet thirty years old when the United States invaded Iraq. His family organization already included a nationwide network of staff and offices, and Sadr quickly leveraged these to assemble a committed militia, the Mahdi Army. He emerged as a powerful and unpredictable force—violently opposed to the American occupation as well as to homegrown Sunni extremists.

Although he is a Shia cleric, Sadr made it clear with his rhetoric and style that he was first and foremost an Iraqi nationalist, not beholden to foreign powers, whether Iran, the United States, or another country. From 2004–08, the Mahdi Army forged a fearsome record of violence, fighting at different times against U.S. forces, Sunni sectarians, and fellow Shia movements. His fighters rallied, at least initially, under the banner of resisting the American occupation. In the first years after Saddam’s fall, the Mahdi Army and the Sadrist political organization made symbolic overtures to non-Shia resistance groups and expressed a willingness to ally with Iraqis of any sect or ethnicity (a commitment evident more in rhetoric than in practice). As a result, and especially in the early years following the invasion, Sadr was one of the few militia commanders who enjoyed at least some grudging respect across sectarian lines. The ensuing decade dulled his sheen somewhat, as his soldiers were implicated in some of the same abuses and sectarian violence as other factions, and his political partisans, the Sadr Movement, proved every bit as susceptible as other parties to the temptations of corruption. In 2008, Sadr officially disbanded his Mahdi Army militia, although much of its structure and membership survived in other guises within the Sadr organization. In 2014, in response to Sistani’s call for fighters to resist the Islamic State, Sadr launched Saraya al-Salam, (“Peace Companies” or “Peace Brigades”), a successor militia to the Mahdi Army which included most of its veteran officers who hadn’t moved on to other, more militant organizations.

Sadr’s trajectory has not been a simple one-way ascent from militia strongman to political player. His story abounds with course-changes and seeming contradictions. For example, he has witheringly attacked the Iraqi political system, even as he has deeply embedded his politicians within it. And though in 2018 he has mounted a new campaign against corruption, throughout the post-invasion years, Sadrists won a hard-earned reputation for epic corruption in their government fiefs, including the lucrative and critical health ministry which they controlled from 2006–07.

Unlikely Partners for Reform

In 2015, the rise of the Islamic State shattered the business-as-usual trajectory of Iraqi politics. Sectarianism had flourished, along with the corrupt spoils system. But foreign influence on Iraqi politics, along with security services crippled by corruption and no-show ghost soldiers, was no match for the Islamic State. Many Iraqis already had reached a breaking point because of raging unemployment and the government’s failure to provide basic services like electricity. Basic services had never been fully restored since the American invasion of 2003, despite years of banner oil profits, mostly lost to corruption. Protest camps sprung up around the country. In Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, followers of Sadr got to know followers of the secular reform parties, including the Communists. Over time, trust grew. Leaders of the secular parties were invited to meet with Sadr.

By the time the Islamic State shattered Iraq’s sense of security, Sadr was already changing course. With the protest movement, he adopted a newly moderate and inclusive rhetoric. Sadr threw his weight behind the protesters. He encouraged his political movement and followers to make common cause with secular reformers and independent technocrats. His followers ceased their very public attacks on homosexuals. “He has undergone a change, an evolution,” said Raid Jahid Fahmi, the secretary general of the Iraqi Communist Party, who has led the secular embrace of the cleric Sadr. “You will find a change in his vocabulary and thinking.”2

“Sadr is ready to cooperate with anyone with Iraqi interests,” said Fahmi. “This was a very important cultural shift.”3

After joining forces with protesters from other factions in 2015, Sadr and his top lieutenants repeatedly met with potential partners. Over time, leaders in the Iraqi Communist Party and the Iraqi Republican Party, led by a secular Sunni pro-American businessman named Saad Janabi, grew convinced they could trust Sadr—and that they would be given an equal role in designing the alliance, even though their parties were much smaller than Sadr’s following.4

“Moqtada al-Sadr is the only person who can summon one million people with a single call,” Janabi said. Secular Iraqis and even some sectarian Sunnis have come to believe Sadr’s nationalist rhetoric, he added.5

In coalition with his new partners, Sadr said he would support an entirely new group of technocratic candidates under a new name. He disbanded his existing “Ahrar” parliamentary bloc, with thirty-four members. He ordered them all not to run for reelection, clearing the way for a new slate of technocrats—the vague term of choice for Sadr and his movement to describe the putative category of professional, independent experts who they believe could improve the Iraqi government’s performance, unfettered by sectarian or political allegiances. Sadr’s new party is called “Istiqama,” which means “integrity,” and the overall coalition with the Communists and other smaller members is called “Sa’iroun,” which means “On the move,” or “Marching,” with the intention of evoking a march toward reform. The alliance’s goals are clear: a civil, secular state, run by technocratic experts who can fight corruption and improve governance.

Sadr’s New Platform in Context

Sadr’s record makes his positioning today all the more interesting. In the pivotal 2018 parliamentary elections, he has declared himself the leading opposition reform candidate. Some of his new claims strain credulity because of his checkered record, but his sheer power and loyal following mean he always has potential as a kingmaker. Electoral math makes unlikely his ambitions of winning the prime minister’s job for his political movement, but he is establishing an entirely new style of politics and rhetoric, which holds critical promise for Iraq and possibly for the entire region.6 First, he has fashioned a potentially inclusive national narrative from the grisly history of sectarian violence that has buffeted Iraq since 2003. Second, he has deftly eclipsed paralyzing political binaries, by forming an alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party and a small array of independent, secular reformists. Third, he has spurred an open discussion of the central problem of Iraqi politics: the “muhasasa” system, most accurately rendered as the “allotment” or “spoils” system.

“This alliance is something new,” said Fahmi, the Communist leader, who has led the secular embrace of Sadr.7 “The political process must shift to a citizenship state from a constituency state. The sectarian quota system is incapable of giving solutions to the problems of the country.”

Since the fall of Saddam’s dictatorships, elections have done nothing to dent the sectarian-based patronage structure in which there is no opposition to the government, but only a shifting free-for-all to feed at the public trough. Elections merely determine what share of power each party gets—the more votes a party secures, the more profitable the ministries to which it lays claim. No successful party has ever refused to take part in the government, joining in the broken-piñata frenzy of corruption that has characterized Iraqi governance at least since Saddam’s era.

The 2018 elections come at a moment when much has changed in Iraqi politics, and Sadr has carefully shaped his movement to make the most of it. The upcoming vote arrives on the heels of a successful military campaign against the Islamic State (in which Sadr’s fighters played an important role), and the coming of age of Iraq’s Shia sectarian militias and Islamist parties. The Shia Islamist militant parties have dominated Iraq since 2003. They have defeated their main external rivals and corralled Kurdish separatism. They have fought each other, sometimes in bitter political contests and at times in outright war, as in 2008 when Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki drove Sadr’s Mahdi Army out of Basra. Today, being a Shia Islamist militia no longer serves as a politically distinguishing identity. All the major electoral coalitions are led by Shia politicians, and most include some Sunni and Kurdish partners and candidates. Fissures within the Shia political space have strengthened other layers of political identity. Politicians now distinguish themselves by their approach to securing Iraq in the future from a resurgence of the Islamic State; balancing the influence of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United States; and solving the nagging problems of poverty, development and corruption. While other Shia political parties are experimenting with nationalist identity in the wake of the campaign against the Islamic State, Sadr has been identifying as a nationalist for years. He stands out further still by his vigorous support for the idea of a civil, even secular, state.

Security officials still worry about continuing threats from the Islamic State, but according to some Iraqi analysts voters have already moved on. Polling, they say, shows that Iraqis are more concerned about livelihoods than anything else. “Security is no longer a priority,” said Sajad Jiyad, head of the Bayan Center, a think tank in Baghdad.8 “They’re asking for jobs, not for security.”

Yet even as Iraqi politicians pivot to face these new voter priorities, the electorate is meeting them with increasing suspicion and cynicism. Sadr has presented himself as something of a political outsider—and certainly not one of the Baghdad elite. His reinvention as a coalition builder enhances his appeal, suggesting he means it when he says he is ready to do business in a new way.

“The state is failing,” said Dhiaa al-Asadi, leader of the current Sadrist bloc in parliament and a political operative very close to Sadr.9 “The existing political elite are part of the problem. They can’t be part of the solution.”

Sadr wants to see the militias formed to fight the Islamic State fully reintegrated into Iraqi government control. He wants sectarian quotas abolished for public sector jobs and government positions. He wants a carefully balanced foreign policy that keeps Iraq equidistant from Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United States. He has also been one of the only important Iraqi Shia leaders to oppose the involvement of Iraqi Shia militias in the Syrian civil war.10 He wants to come to terms with separatist Kurds. Above all, he wants to jumpstart the moribund economy to provide jobs and salaries to Iraqis—the poorest of whom are disproportionately part of Sadr’s following.

In this context, Sadr’s frontal challenge to the central narratives of Iraqi governance since 2003 has the potential to force the ruling parties to shift their rhetoric and approach. Indeed, the process can already be seen in action.

Bridging Old Rifts

Take, for example, Sadr’s changing relationship with Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who, despite reservations about Sadr that have at times erupted into violent confrontation, has continued to court and collaborate with the cleric. Abadi has gone so far as to adopt some of Sadr’s rhetoric. One billboard at the entrance to Baghdad shows Abadi’s face and reads, “corruption and terrorism have one face,” echoing the Sadrist protest slogan, “corruption is terrorism.”

Abadi’s wary embrace of Sadr is especially significant given that the many of the latter’s supporters view Abadi as a villain. One recent demonstration, in February, marked the one-year anniversary of the death of fourteen demonstrators—killed at the hands of Abadi’s security forces while marching toward the Green Zone. Marchers carried flag-draped coffins commemorating the “martyrs for reform” in the same manner that they would honor martyrs who died fighting the Islamic State.

Abadi and his allies have opted to accept Sadr as a potential partner, although Sadr’s critical rhetoric has made them wary. “I think we should distinguish between the election campaign and the reality,” said Sadiq al-Rikabi, a member of parliament and a close ally of the prime minister.11 “It is very easy to stand against corruption,” he added, but much harder to articulate tangible policy proposals.

Perhaps even more significant than Sadr’s partial rapprochement with Abadi is that with Sistani. Despite Sadr’s persistent popularity, Sistani’s influence remains more important—but also more diffuse. Sistani’s clout with Iraqi Shia is not absolute nor instrumental; he doesn’t directly control any political parties or militias, and despite his extensive efforts, he has been unable to persuade Shia politicians to avoid corruption, violence and sectarianism. Still, his edicts hold force. It was a fatwa from Sistani in 2014 that created the popular mobilization units (“al-hashd al-sha’abi,” or PMUs). Almost all Shia in Iraq heed Sistani’s edicts, and he has been credited on multiple occasions with limiting the deleterious impact of Iraq’s worst crises. Sistani has telegraphed his disappointment with the record of the Shia Islamist parties that have dominated Iraq’s government since the 2005 elections. The Shia parties almost uniformly try to claim the approval of Sistani and the other senior Shia clerics, even when Sistani has made clear that he supports none of them. Sistani warned leaders of the Shia militias not to parlay their battlefield success into political campaigns, but most of them ignored the order, to Sistani’s chagrin.

In an interview, a representative of Sistani criticized militia leaders for seeking “political advantage” from the “blood sacrifice” that Iraqis of all sects made in the resistance against the Islamic State.12 As the parliamentary campaign has heated up, Sistani has made his displeasure even more clear. One cleric close to Sistani went on Furat Television to warn voters not to make their choice based on sect.13 “The corrupt people we have voted for have robbed the nation. We ought to not vote for them again, even if they are members of our clan or sect,” said the cleric, Rashid al-Husseini.14 “I would rather trust a faithful Christian than a corrupt Shia.”

Historically, Sadr has been at odds with Sistani and the other senior clerics in the marjaiya. In the current campaign, however, he has closely shadowed Sistani’s pronouncements about corruption and the need to elect new leaders. In recent statements, Sadr has addressed skeptical voters who have lost faith in the political process because of the corruption and failures of previous Iraqi governments, including those with the participation of Sadrists. “We will not be deceived by the lies again,” Sadr wrote in an April 14, 2018 statement.15 His own movement’s previous failures, he said, “give the motivation and determination to succeed in this election.”

On April 4, 2018, Sadr released a series of arguments against boycotting the elections. “Some ask, and say: the corrupt and the old faces will stay in power whether we vote or not,” Sadr wrote. He offered thirteen rebuttals, evoking religious loyalty, patriotism, optimism, and the responsibility of citizenship.16

In today’s Iraq, Sadr boasts a unique status.17 He can count on nearly absolute devotion from his rank-and-file followers, his organization, his political party and his militia. Even Sadr’s opponents recognize his political heft. In this, he is different from other Iraqi religious leaders only in degree: Mowaffak al-Rubaie, a former national security adviser who is close to several senior Iraqi politicians, said that millions of Iraqis venerate clerics and will do whatever those clerics instruct.18 During a visit by Sadr to the Kadhamiya shrine in Baghdad, Rubaie recalled, Sadr’s followers crowded the cleric’s jeep to touch the dirt on its wheels, which they smeared on their heads as a blessing. “If he orders these people to set themselves on fire, they will do it,” he said.

Sadr’s positions have appealed to Iraqis who are weary of conflict but seek to maintain dignity and integrity in their foreign relations. For example, Sadr has softened his rhetoric about secularists, and has been willing to mend fences with Saudi Arabia and criticize Iran. But at the same time, he has maintained a hard line against the United States, whose influence in Iraq he considers wholly malign.

The fact that those positions are accommodating while remaining tough and without being overly compromising—much like his evolving relationships with Abadi and Sistani—make his calls for unity that more meaningful.

“Healing is gradual,” he said in the April 14 statement. Iraq has never before experimented with professional technocratic politicians, “without any partisan or religious or ideological or ethnical indications, to choose the most effective and the best [leaders] for the love of Iraq, and the love of Iraq is of faith.”

Managing Expectations

If this account of Sadr’s well-timed transformation into a champion of nonsectarian political reform sounds a little too gung ho, there are plenty of structural and historical reasons to readjust expectations to a more realistic level.

The results of the May 12 election are likely to set in motion a long negotiation process; many seasoned Iraqi politicians and analysts believe the outcome will be another unity government like all those that have ruled Iraq since the U.S. occupation, with goodies and power divided among sectarian parties. Sadr has pulled many about-faces before; he may tire of the alliance with secular parties, or he might decide he can better serve his constituents by joining yet another weak coalition government. “Moqtada al-Sadr has been on television and in politics for fifteen years and he has accomplished none of his goals,” said one political insider close to the government. “He has been revealed to be someone who cannot be trusted.”19

Fighting Sectarianism

Specific aspects of Sadr’s past raise questions about his sincerity. For example, despite his maverick image, he has played his part in the problem of sectarianism. The Mahdi Army orchestrated some of the worst ethnic cleansing and sectarian killings of 2006, although Sadr subsequently pulled his loyalists back. Many of his extremist supporters defected to other organizations or founded their own, like Qais al-Khazali, who is now the leader of Asaib al-Haq, a Shia militia close to Iran.

Some secular leaders never overcame their mistrust of Sadr, with his religious background and history of secrecy and political about-faces. One of the secular reform leaders who rejected the coalition is Shirouk al-Abayachi, leader of the National Civil Movement and a member of parliament.20 Sadr’s organization is “foggy” and evasive, she said. “One year ago they would call us infidels,” she said. “We don’t know what they want from us.” If the Sadrist alliance does well in elections, she said, history suggests that Sadr and his lieutenants will make the important decisions, rather than deferring to the independent secularists from tiny parties. “We don’t just want seats in parliament,” Abayachi said. “We want to build a clean alternative.”

Despite his conciliatory reform rhetoric, Sadr has been willing to turn to outright confrontation with the state. Despite his status as a junior partner in the Iraqi government, Sadr personally broke through the security cordonsurrounding Baghdad’s Green Zone in March 2016.21 His followers set up a protest camp in the heart of the government, even briefly occupying parliament and the prime minister’s office.

Pervasive Corruption

When it comes to fighting corruption, there are similar reasons to moderate enthusiasm for Sadr.

Existing anti-corruption efforts suggest it will be difficult to make meaningful inroads against the spoils system. “The system needs to be reformed but there is no incentive to reform,” said Ali al-Mawlawi, director of research at the Baghdad think tank the Bayan Center.22 “The government has hard evidence, but the corrupt judiciary won’t prosecute.”

Even Sadr’s own politicians have struggled to have an impact, and critics of Sadr’s reform program point out that it is short on specifics. Jumaa Diwan al-Badali is a Sadrist member of parliament who represents the poor Baghdad district of Sadr City (which takes its name from Moqtada al-Sadr’s father, Mohammad al-Sadr); Badali is also the rapporteur of parliament’s integrity committee, in charge of investigating corruption. His experience shows the limits of any serious effort at reform. His committee has publicized some problematic contracts, often resorting to media leaks to force the government to pay attention. Parliamentarians have uncovered kickbacks and fishy contracts in the department of defense, including one case, Badali said, where the department attempted to buy subpar and nonexistent equipment for the fight against the Islamic State.23

The biggest contract they stopped was a $2.5 billion weapons deal with China, which was part of the 2017 budget. Badali believes the U.S. encourages corruption in Iraq as a way of keeping the country and its security forces weak. “I don’t accept the prime minister’s depiction of Iraq as a pool of corruption,” he said. “We are a country with some corruption. We are not the most corrupt country in the world.”

Aside from the general difficulty of rooting out corruption, Sadr and his allies are hardly innocent of graft themselves. Sadr’s militia, the Saraya Salam (“Peace Brigades”), a PMU created in 2014 from the remnants of the Mahdi Army, has benefited from government funding. Corruption clearly played a role in eroding the combat readiness of Iraq’s security forces prior to the rise of the Islamic State, but the rise of new security institutions, including the PMUs, has only fueled the type of corrupt militia patronage that has hobbled the central government.

Over the years since 2003, Sadrist ministers and members of parliament joined the corruption frenzy as well, taking kickbacks and doling out patronage jobs through ministries under their control. Sadr’s principal secular ally, the Iraqi Communist Party, also enjoyed influence through the spoils system, winning positions in the cabinet despite very winning very few votes. Fahmi, the current Communist leader, served as minister of science and technology from 2006 to 2010. Fahmi preserved his reputation for probity through his time in government, although—critics of the Sadrist reform project are quick to point out—he wasn’t able to roll back corruption by other parties in government.

“Who can fight corruption?” said Ahmed al-Krayem, a tribal leader and provincial politician who alleges that Sadr’s followers and fighters participate in the same kickbacks and extortion schemes as every other Iraqi political party and militia group.24 “The Sadrists won’t fight corruption.” Even the prime minister, Krayem pointed out, has been dogged by allegations of corruption from his earlier stints in government before taking over as premier.

Interestingly, Sadr doesn’t refute charges that his own movement is implicated in the failures of past attempts to root out corruption, but rather insists that change depends on continuing engagement and changing tactics. “We didn’t hope to be corrupted,” he wrote in answer to one supplicant who asked how Sadr justifies his political campaign given that his movement has participated in every single one of the corrupt governments since 2003. “We are rising up against the political process from the inside, rather than from the outside.”

Profound Political Problems

Some of the differences within the Sa’iroun coalition seem unbridgeable. Sadr’s Shia followers fought the United States and died in droves. Janabi’s secular followers include many elite Sunnis who are openly fond of the Americans. The Communists, meanwhile, have a long history of tensions with the clergy. Still, supporters of the alliance say these differences won’t lead to political fissures. “Sadr can control his people if there are problems. We will control our followers,” Janabi said. “We agree about fighting sectarianism.”

Another sticking point for Sadr’s agenda may be that the idea of apolitical “technocrats” who just get the job done may be something of a fantasy—at least for Iraq.

Even Sadr’s supporters point out that technocrats can only have impact if they are effective politicians. “I don’t believe in technocrats,” said Hakim al-Zamili, an influential Sadr lieutenant who runs the parliament’s security committee.25“Only a strong politician with a base in a political party can succeed. The country is full of militias, people with weapons in the streets. An independent technocrat without a political party can’t do anything.”

Independents have served as ministers in Iraq since 2003, and none has managed to change the system. The types of figures who can change the system, Zamili said, are tough political veterans with the backing of formidable parties. “Maybe a political technocrat like me can do something,” he said. “No one can threaten me, no militia. I can speak, I can interrupt someone, no one can stop me.”

Iraq’s system is broken; it might benefit from repairs, but Iraqi voters should not expect a wholesale revolution. “Let’s be honest—we can’t accomplish everything we are planning,” Zamili acknowledged.

Murder in Samarra

Power politics in Iraq can play out at a visceral level, and one recent incident has underlined both the frailty of Sadr’s new vision, and its promise.

Sadr has repeatedly taken the position that there should be only one central authority in Iraq—the state—and that all militias must be integrated into government control. At the same time, he commands thousands of militia fighters in the Saraya Salam, most of them stationed in the flashpoint shrine city of Samarra, north of Baghdad. Samarra is a mostly Sunni city that is home to one of the most holy spots for Shia Muslims, the site where it is believed that the twelfth imam went into occultation in the ninth century. Sunni extremists blew up the Shia shrine in Samarra in February 2006, setting off one of the deadliest periods of sectarian fighting in Iraq. Islamic State fighters held sway in Samarra until Shia militias drove them out in 2014.

Since 2015, Sadr’s militia has held sole control of the city. According to Sadrists and Saraya Salam commanders and fighters, their tenure in the city has been a model of success. They have formed partnerships with local business owners and tribal leaders, most of them Sunni, and have restored security and the business that comes with pilgrimage traffic. Critics accuse the Sadrists of ruling the city with an iron fist, detaining political critics, and extorting money from local traders and business owners. The accusations were repeated in multiple interviews with the author, and aren’t out of the ordinary in Iraq; in fact, the accusations levied against the Sadrist militia are much milder than those heard in zones ruled by other Shia militias, where displaced Sunnis live in fear of disappearance and, in some places, of summary execution.

The fact remains that the Sadrists are running a fiefdom, a state-within-a-state in Samarra; while such behavior is the norm in today’s fragmented Iraq, it contradicts the Sadrist platform of reforming the state under a unified nationalist banner. In March, the dangerous equilibrium resulting from so many overlapping security forces collapsed with a shootout between allies in Samarra. On Tuesday, March 13, the prime minister’s personal security detail was driving north in a convoy, preparing for Abadi’s planned visit later in the week to Mosul. The road took them through Samarra. At the town’s main checkpoint, according to two members of a committee that investigated the incident, the convoy refused to stop at the Saraya Salam checkpoint, as they are required to by law.26 Commandos from Battalion 57 of the Iraqi Army, the prime minister’s special unit, went so far as to confiscate weapons from some of the Saraya Salam fighters at the checkpoint. “It was humiliating,” said one of the members of the investigative committee that visited Samarra days later.27The angry fighters radioed ahead to the next checkpoint, a kilometer away, where Saraya Salam militiamen blocked the road with Humvees and confronted the convoy. Dozens of gleaming black sports utility vehicles swarmed the checkpoint. The army unit then fired toward the checkpoint. The Sadrists returned fire, killing Brigadier Sherif Ismail, the battalion commander and a trusted supporter of the prime minister.

Both Sadr and Prime Minister Abadi avoided public recriminations, and ultimately the killing was settled through a tribal agreement. The military unit, according to the investigative committee, was at fault for ignoring proper checkpoint procedures. “We need to develop a culture of respect,” said Zamili, the Sadr lieutenant, who was one of four members of the investigative committee. Another member of the investigative committee, who is not from either the prime minister’s or from Sadr’s bloc, blamed a lack of professionalism. “They were arrogant. They wanted to show off, they didn’t want to follow the rules,” the member said. “It was 100 percent an accident.” Political, military and economic power are inextricably intertwined, and state authority is severely compromised. This particular killing strained but did not break the alliance between Abadi and Sadr, but it revealed yet another potential point of rupture. Tellingly, it was resolved not by the judicial system or by a formal political process, but by a combination of ad hoc investigation and informal tribal justice.

Turning Point Election

The 2018 elections will set the course for Iraq’s government for at least another four years. If the current spoils system continues, with every major party joining into yet another ineffective unity government, Iraq can expect to repeat similar crises. It will be nearly impossible to maintain the effective national security approach that defeated the Islamic State—an approach that required unified command, mass mobilization, and help from all of Iraq’s competing allies, including Iran and the United States. Economic development will require warm relations with Iran, the United States and Saudi Arabia, and, at the very least, a curtailing of rampant corruption. None of these improvements will come to pass without a powerful prime minister, a meaningful opposition, and competent ministers. Sadr’s trailblazing coalition marks a crucial possibility for Iraq: the mainstreaming of civic-secular nationalism, and the passing of national politics from sectarianism into a new phase. More emphatically than any other leader, Sadr has abandoned religious and sectarian discourse, showing that a Shia cleric with a sectarian base can embrace civic, secular politics. There is, of course, ample precedent for such politics in the last century of Arab political history, but sadly, very little among contemporary Iraqi political leaders.

An informal quota system reserves the most important job, prime minister, for a Shia, and the presidency and speaker of parliament for a Kurd and Sunni Arab respectively. If this new tradition survives another electoral cycle, it will fast become the kind of pernicious unwritten tradition that cannot be changed—like Lebanon’s sectarian quotas, which have become unassailable even though they are not in the constitution.

In his alliance with Communists and secularists, Sadr has mainstreamed civic politics. If he sticks with his current course, he can also set an example for other leaders who are willing to move past their origins as sectarians, clerics, or militia leaders. Despite his pointed anti-Americanism and history of armed resistance, the United States should welcome Sadr’s new role. So should Iran, which hoped to make Sadr into one of its proteges before the cleric broke with Tehran as well. Sadr’s broadsides against the United States (his lieutenants regularly brand the Baghdad embassy as a “devil” spreading sedition and strife in Iraq) shouldn’t obscure the common interests he shares with the United States and its Iraqi partners: building a strong, effective government and encouraging a nonsectarian, inclusive national identity that can help end the cycle of sectarian violence.

Sadr’s new rhetoric, and his secular political alliance, mark one of the most promising developments in contemporary Iraqi politics. There are plenty of reasons to question his sincerity, or the durability of the partnerships he has forged since 2015, but those partnerships hold the potential to change the tenor of the entire political playing field. Sadr’s reinvention of himself from militant cleric to nationalist anti-sectarian statesman comes at a time when other sectarian movements have begun to realize that they will need support from multiple constituencies in order to survive politically. In the likely event that the alliance doesn’t win enough seats to form a government, it can contribute still more profoundly to Iraq’s political development by opting to stay out of power and serve as a parliamentary opposition. Iraq stands at a turning point, where its largely sectarian political movements are experimenting with nonsectarian politics, and where its ruling class is confronting the dead-end to which the spoils system has brought the country. Sadr’s gambit stands a chance, albeit a slim one, of catalyzing the political transformation that Iraq so sorely needs.

To be sure, Iraq will still play host to endemic corruption and patronage, but a sharp change in politics can expand the government’s agenda to include long-term governance along with the usual business of padding state contracts and doling out ghost jobs. Without the sort of transformative nationalist, professional, and anti-corruption politics advocated by Sadr, Iraq is sure to face an ongoing cycle of crises that will destabilize not only Iraq, but also its neighbors and U.S. interests in the Middle East.

A Reckoning Will Come in Syria

A missile is seen crossing over Damascus, Syria April 14, 2018. SANA/Handout via REUTERS[Published in The Atlantic.]

It is undoubtedly a good thing that a small international coalition of the willing responded to Syria’s latest chemical outrage with a limited military strike. But it marks only the first step in an effective strategy to stop Syria’s use of chemical weapons—and more importantly, to hold Russia accountable for its promise to oversee a chemical weapons-free Syria.

Syria and Russia have displayed characteristic bluster and dishonesty, warning of “consequences” for a crisis that the Syrians themselves provoked by apparently violating, once again, their 2013 agreement not to use chemical weapons. Any confrontation with destabilizing bullies is dangerous, and there is no predicting whether and how they’ll respond.

Even a limited and justified effort to contain Syria and its allies carries a risk of escalation. The Trump administration, with its capricious chief executive and broken policy-making process, is ill equipped to forge the sort of complex strategy needed to manage Russia, Syria, Iran, and a Middle East in conflict. Nor has it so far displayed much interest in building the international cooperation necessary to implement such a strategy—although it was a pleasant development that the United States was joined this time by France and the U.K. rather than proceeding unilaterally. However, the considerable drawbacks of the Trump administration don’t give the West a pass when it comes to Syrian use of chemical weapons, and Russia’s belligerent expansionism. Both need to be checked and contained, even considering the additional risks Trump creates.

In order to have any real impact on chemical weapons use, the response needs to be sustained. Every time the regime uses chemical weapons, there needs to be a retaliation, which specifically targets the regime’s chemical-weapons capacity—command and control, delivery mechanisms including aircraft and bases, storage, research, and the like. A political strategy is indispensable as well. Since Russia is the guarantor of the failed 2013 chemical weapons agreement, the West needs to keep Russia on the hook for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons. The Pentagon chief suggested that these strikes were a one-off, and only time will tell which of Trump’s preferences prevail.

Deft diplomacy will also be necessary to reduce the risks of wider war. It doesn’t help that Trump is undermining the nuclear deal with Iran at the same time as he is ratcheting up the stakes in Syria. One key determinant now is how much Russia is willing to add action to match its relentless campaign of lies and bluster about Syria and chemical weapons. Another is whether Iran, Assad, and Hezbollah are willing to sit on their hands after these strikes. In the past, all three have been willing to refrain from action despite angry promises.

* * *

The problem is the context. Any American action in the Middle East ought to be embedded in a comprehensive, engaged strategy—which is not likely to be forthcoming. Today, we can be sure that America’s significant moves—from proposals to withdraw military assets fighting ISIS in Syria and Iraq, to promises to degrade the capabilities of Bashar al-Assad or limit the reach of Hezbollah or Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps—will land à la carte, increasing the danger of miscalculation and violent, destabilizing escalation.

At stake is how to manage disorder in the Middle East, and more important still, where to draw the line with a resurgent Russia.

Containing rival powers is an art, not a science. Military planners talk about the “escalation ladder” as if it were a chemical equation, but in reality escalation hinges on unpredictable questions of politics, interests, psychology, hard power, and willingness to deploy it.

Obama’s strategy could most simply be understood as a desire to contain regional fires with minimal involvement, while keeping an equal distance from regional antagonists, including Saudi Arabia and Iran, and difficult regional allies including Turkey and Israel. The U.S. got involved in the fight against ISIS, by this logic, with minimal resources and local alliances that it knew couldn’t outlive the immediate counter-terrorism operation.

In the Syrian context, Obama early on made clear that the United States commitment to principles of democracy and human rights would remain primarily rhetorical. Today, the United States has discarded even many of the rhetorical trappings of American exceptionalism. Trump has made clear that he doesn’t apply a moral calculus to superpower behavior. But he’s also expressed personal outrage about Syria’s use of chemical weapons—and he visibly takes umbrage at being personally embarrassed or humiliated.

Whether one thinks it’s wise or fully baked, President Trump also has a Middle East strategy. He wants to reduce America’s footprint, and disown any responsibility for the region’s wars, as if America played no role in starting them and suffers no strategic consequence from their trajectory. He wants to outsource regional security management to regional allies. Most of this is continuous with Obama’s approach, except when it comes to regional alliances; Obama attempted a “pox on both your houses” balance among all of America’s difficult allies. In his biggest departure from his predecessor, Trump has tilted fully to the Saudi Arabian side of the regional dispute, and has erased what little daylight separated American and Israeli priorities in the Middle East.

This is the bedrock of Trump’s moves in the region—moves that are all the more consequential because they are overtly about confronting, or trying to check, Iran and Russia.

* * *

The United States has a critical national interest in reestablishing the chemical weapons taboo. It also has countless other equities in the Middle East that require sustained attention and investment, of diplomatic, economic, and military resources. A short list of the most urgent priorities includes preventing the resurgence of ISIS or its successors; supporting governance in Iraq; limiting the reach and power of militias supported by Iran; and reversing the destabilizing human and international strategic toll of the world’s largest refugee crisis since World War II. A major regional war will only make things worse.

Given the stated priorities of the president, the most realistic possibility is an incomplete, and possibly destabilizing policy of confrontation, containment, and reestablishment of international norms.

But a reckoning can’t be deferred forever. Iran has been surging further and further afield in the Middle East, to great effect. Russia has been testing the West’s limits mercilessly since the invasion of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. At some point, the United States and its allies will stand up to this expansionist behavior, although there’s wide latitude about where to set limits. When the West, or some subset of NATO, does confront Russian ambitions, there’s no pat set of rules to keep us safe. Such confrontations are inevitable, and dangerous, and unpredictable. The best we can do is enter into them carefully, with as many strong allies as possible, and clearly stated, limited expectations about what we intend to accomplish.

The United States and its allies also need to more carefully distinguish things they dislike (Iranian influence in Iraq) from things they won’t tolerate (Hezbollah and Iran building permanent military infrastructure in the Golan). Rhetoric in the region often conflates the two. Israeli officials, for instance, talk about “intolerable” developments in Syria, but in practice their security policy often allows for a great deal of ambiguity about just what level of military threat they’re willing to tolerate along their frontiers. Iran, Hezbollah, and now Russia have made grandiose claims about retaliating if the United States takes action, but after past strikes by both the United States and Israel, the actual response has been quite restrained.

The United States and its allies need to set limited, achievable goals. The U.S. might for instance stand firm against the use of chemical weapons, or against new military campaigns against sovereign states, but it can’t very well seek to turn back the clock to a Syria free of Russian and Iranian influence.

In addition, the United States can help the world remember who is the author of this dangerous impasse: Syria, Iran, and Russia, who have serially transgressed the laws of war, lied in international forums, and mocked countless agreements, including the shambolic deal that was supposed to rid Syria of chemical weapons in 2013. This won’t justify American actions or give them political cover, but it is a key reason why we’re in such a difficult position in the first place. Despite American restraint, or even American willingness to tolerate war crimes by Syria and its allies, Syria and its allies have insisted on pushing past every limit and exhausting the world’s willingness to turn a blind eye toward abuses so long as those abuses stay within national boundaries.

Finally, to have any impact at all the United States will need to pay consistent and sustained attention. Russia, Syria, and Iran have gotten away with murder, literally, and have found themselves able to run circles around Western governments that still care to some extent about international norms and institutions. They are dangerous, but they are far weaker than their words would suggest. The West cannot deter every action it does not like, yet it can draw boundaries and impose a cost—but it must do so consistently.

This weekend’s strikes have established a bar and set a perilous, but unavoidable, process in motion. What counts is what comes next.

The Logic of Assad’s Brutality

A child and a man are seen in hospital in the besieged town of Douma, Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, Syria. Picture taken February 25,2018. REUTERS/Bassam Khabieh

[Published in The Atlantic.]

Bashar al-Assad, the president of Syria, might have great contempt for the sanctity of human life, but he is not a reckless strategist. Since 2011, he has prosecuted an uncompromising war against his own population. He has committed many of his most egregious war crimes strategically—sometimes to eliminate civilians who would rather die than live under his rule, sometimes to neuter an international order that occasionally threatens to limit his power, and sometimes, as with his use of chemical weapons, to accomplish both goals at once. When he does wrong, he does it consciously and with intended effect. His crimes are not accidents.

The Syrian regime’s suspected chemical-weapons attack on Saturday in Douma, a suburb of Damascus, suggests that Assad and his allies have accomplished many of their primary war aims, and are now seeking to secure their hegemony in the Levant. But two major factors still complicate Assad’s plans. One is Syria’s population, which to this day includes rebels who will fight to the death and civilians who nonviolently but fundamentally reject his violent, totalitarian rule. The second is President Donald Trump, who has expressed a determination to pull out of Syria entirely, but at the same time has demonstrated a revulsion at Assad’s use of chemical weapons.

Almost precisely one year ago, Assad unleashed chemical weapons against civilians in rural Idlib province, provoking international outrage and a symbolic, but still significant, missile strike ordered by Trump against the airbase from which the attacks were reportedly launched. Assad’s regime was responsible for the attacks and its Russian backers were fully in the know, later evidence suggested, but Damascus and Moscow lied wantonly in their hollow denials.

This weekend, it appears, Assad’s regime struck again. Fighters in Douma refused a one-sided ceasefire agreement, and haven’t buckled despite years of starvation siege warfare and indiscriminate bombing. In what has become a familiar chain of events, the regime groomed public opinion by airing accusations that the rebels might organize a false-flag chemical attack in order to attract international sympathy. An apparent chemical attack followed, killing at least 25 and wounding more than 500, according to unconfirmed reports from rescue workers and the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations. The Syrian government and the Russians have once again blamed the rebels, knowing that it will take months before solid evidence emerges, by which point most attention will have turned elsewhere. The pattern is by now predictable. In all likelihood, solid, independent evidence will soon emerge linking the attacks to the Syrian regime.

Assad already has unraveled the global taboo against chemical weapons, in the process exposing the incoherence of the international community. Syria has exposed the international liberal order as a convenient illusion. Western bromides of “never again” meant nothing when a determined dictator with hefty international backers committed crimes against humanity.

Why now? This latest attack in Ghouta, if it holds to the pattern, makes perfect sense in the calculus of Assad, Vladimir Putin, and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The successful trio wants first and foremost to subdue the remaining rebels in Syria, with an eye toward the several million people remaining in rebel-held Idlib province. A particularly heinous death for the holdouts in Ghouta, according to this military logic, might discourage the rebels in Idlib from fighting to the bitter end. Equally important, however, is the desire to corral Trump as Syria, Russia, and Iran did his predecessor, Barack Obama.

After the humiliating August 2013 “non-strike event,” when Obama changed his mind about his “red line” and decided not to react to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, the Syrians had America in a box. The White House signed up for a chemical disarmament plan that proved a farce. By the time the agreement had unraveled and Assad was back to using chemical weapons against Syrian citizens, the public no longer cared and Obama was busy discussing his foreign policy legacy.

Trump’s Middle East policy remains a mystery. He has long appeared unconcerned with rising Russian power in the Middle East, but today tweeted that there would be a “big price” for Russia, Iran, and Syria to pay. He seems to prefer a smaller U.S. military footprint, talking repeatedly about pulling troops out of Syria and Iraq. He’s savaged the deal that shelved Iran’s nuclear program, and doesn’t appear impressed by the shabby chemical-weapons agreement in Syria. He doesn’t seem interested in a long-term strategic engagement in the Arab world, but he’s also not interested in propping up the status quo. His reaction to the Khan Sheikhoun attack a year ago aligned with these preferences: He abhorred the attack and spoke with uncharacteristic humanity about the children killed by Assad, and ordered a pointed but limited response. He wasn’t interested in escalating or intervening against Russia or Assad, but he also had no interest in pacifying or reassuring them.

One result of Trump’s confusing Syria policy is that Assad and his backers can’t quite be sure what America is planning—a pullout or a pushback. Hence another chemical attack, which will test the range of America’s response and, perhaps, will paint Trump into the same corner where Obama’s Syria policy languished.

For Assad, there is utility in such a feint, and no real risk. In 2013, he and the rest of the region braced in fear for an expected American response, which was widely expected to jolt the regional state of affairs. Assad has learned his lessons since then. No meaningful American response will be forthcoming, no matter how hideous the war crime. America remains deep in strategic drift, unsure of why it continues to engage in the Middle East, and prone to spasms of hyperactivity rather than sustained attention.

Although we can’t be sure—yet—exactly what happened in Ghouta, we can be confident that it was no accident. Assad is determined to cement his grip once again over Syria, no matter how thoroughly he has to destroy his country in order to restore it. And with Putin’s backing, he is determined to thoroughly discredit what remains of the international community and U.S. leadership. They can’t be sure what Trump will do, but their apparent cavalier use of chemical weapons on the one-year anniversary of the Khan Sheikhoun attacks suggests they’re reasonably confident that the U.S. president won’t take serious action.

This most recent attack, as tragic as it is, is no turning point. It’s more of the same from Assad and his allies, as they solidify the grisly, dangerous norms that they’ve been busy enshrining since 2013.

Managing Syrian Conflict May Be Possible. Resolving It Isn’t.

[Report for The Century Foundation.]

How much, if at all, should the West be involved in Syria as Bashar al-Assad rebuilds the country? The United States and its allies in Europe failed in almost all their policy aims, and the dictator they sought to topple appears to have survived comfortably in power. TCF fellows Thanassis Cambanis and Sam Heller initially set out to write a joint policy recommendation for how the West should approach the conundrums of aid and reconstruction in Syria; but our disagreements proved more instructive than our common ground. What follows is a written dialogue about the Western policy options for dealing with Syria going forward on matters of humanitarian aid, reconstruction, diplomatic relations, and other potential areas of cooperation.

Thanassis Cambanis: Is there any such thing, at this stage, as a good U.S. or Western policy for Syria? This question has been coming up with increasing intensity as the conflict winds down into a final stage. Notwithstanding some arguments that the conflict might drag on for quite a few years, I am convinced that—absent some major game-changing shift—Bashar al-Assad and his allies have won the war. Damascus is now focused on reconquering all of Syrian territory, consolidating its authority, and rebuilding its networks and institutions.

I want us to address a range of questions in this dialogue, including some disagreements between us, about aid, reconstruction, the ethics of engagement with Syria, and the West’s strategic interests in Syria going forward. The recent focus has rightly been on the military imbroglio in northern Syria, which involves Turkey, the United States, and their various Arab and Kurdish proxies. In the long term, however, the West’s most intractable problems have to do with Assad and his government in Damascus.

For the United States and its European partners, this is an ugly and confusing moment. Washington and its hardline anti-Assad allies in Europe seem stuck: they failed to topple Assad, and they don’t want to deal with him. They made strategic commitments in Syria that no longer make sense, but they recognize that Syria is too important for them to try to simply wash their hands of it. Now they have to figure out how to deal with a Syria still under Assad, and still in conflict.

Some of the Western interests at stake in Syria are obvious. Pressing concerns like the Islamic State, or the stabilization of the vast desert zone that stretches between Baghdad and Damascus, require unstinting attention. There are systemic pressures to engage with Assad from many Western quarters, as well. Humanitarians want to distribute aid in regime-controlled Syria, no matter how problematic the regime’s practices of preventing access to civilians considered disloyal. Public and private interests want the West to invest in rebuilding Syria, some for cynical reasons of profit, others for well-meaning reasons of wanting to help the Syrian population that has suffered from a grueling war. Intelligence and security services want to share information with Damascus and engage in joint counterterrorism efforts. Diplomats want to reopen communications channels that were hastily severed during the brief period when many Westerns assumed that Assad was on his way out.