Stop Being Scared

[Originally published in The Boston Globe.]

President Obama and his presumptive challenger Mitt Romney agree on at least one important matter: the world these days is a terrifying place. Romney talks about the “bewildering” array of threats; Obama about the perils of nuclear weapons in the wrong hands. They differ only on the details.

A bipartisan emphasis on threats from outside has always been a hallmark of American foreign-policy thinking, but it has grown more widespread and more heightened in the decade since 9/11. General Martin E. Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, captured the spirit when he spoke in front of Congress recently: “It’s the most dangerous period in my military career, 38 years,” he said. “I wake up every morning waiting for that cyberattack or waiting for that terrorist attack or waiting for that nuclear proliferation.”

The unpredictability and extremism of America’s enemies today, the thinking goes, makes them even more threatening than our old conventional foes. The old enemy was distant armies and rival ideologies; today, it’s a theocracy with missiles, or a lone wolf trying to detonate a suitcase nuke in an American city.

But what if the entire political and foreign policy elite is wrong? What if America is safer than it ever has been before, and by focusing on imagined and exaggerated dangers it is misplacing its priorities?

That’s the bombshell argument put forth by a pair of policy thinkers in the influential journal Foreign Affairs. In an essay entitled “Clear and Present Safety: The United States Is More Secure Than Washington Thinks,” authors Micah Zenko and Michael A. Cohen argue that that American policy leaders have fallen into a nearly universal error. Across the ideological board, our leaders and experts genuinely believe that the world has gotten increasingly dangerous for America, while all available evidence suggests exactly the opposite: we’re safer than we’ve ever been.

“The United States faces no serious threats, no great-power rival, and no near-term competition for the role of global hegemon,” Cohen says. “Yet this reality of the 21st century is simply not reflected in US foreign policy debates or national security strategy.”

It might seem that the extra caution couldn’t hurt. But Zenko and Cohen argue that excessive worry about security leads America to focus money and attention on the wrong things, sometimes exacerbating the problems it seeks to prevent. If Americans and their leaders recognized just how safe they are, they would spend less on the military and more on the slow nagging problems that undermine our economy and security in less dramatic ways: creeping threats like refugee flows, climate change, and pandemics. More important, the United States would avoid applying military solutions to non-military problems, which they argue has made containable problems like terrorism worse. In effect, they argue, the United States should keep a pared-down military in reserve for traditional military rivals. The bulk of America’s security efforts could then be spent on remedies like policing and development work — more appropriate responses to the terrorism and global crime syndicates that understandably drive our fears.

Why should Americans feel so secure right now? Zenko and Cohen write that a calm appraisal of global trends belies the danger consensus. There are fewer violent conflicts than at almost any point in history, and a greater number of democracies. None of the states that compete with America come close to matching its economic and military might. Life expectancy is up, and so is prosperity. As vulnerable as the nation felt in the wake of 9/11, American soil is still remarkably insulated from attack.

Nonetheless, more than two-thirds of the members of the Council on Foreign Relations — as good a cross-section of the foreign-policy brain trust as there is — said in a 2009 Pew Survey that the world today was as dangerous, or even more so, than during the Cold War. Other surveys of experts and opinion-makers showed the same thing: the overwhelming majority of experts believe the world is becoming more dangerous. Zenko and Cohen claim, essentially, that the entire foreign policy elite has fallen prey to a long-term error in thinking.

“More people have died in America since 9/11 crushed by furniture than from terrorism,” Zenko says in an interview. “But that’s not an interesting story to tell. People have a cognitive bias toward threats they can perceive.”

The paper’s authors are, in effect, skewering their own peers. Zenko is a Council on Foreign Relations political scientist with a PhD from Brandeis. Cohen (a colleague of mine at The Century Foundation, and a previous contributor to Ideas) worked as a speechwriter in the Clinton administration and has been a mainstay in the thinktank world for a decade.

Zenko and Cohen point out that there are plenty of good-faith reasons that experts tend to overestimate our national risk. A raft of psychological research from the last two decades that shows human nature is biased to exaggerate the threat of rare events like terrorist attacks and underestimate the threat from common ones like heart attacks. And security policy in general is extremely risk-averse: we expect our military and intelligence community to tolerate no failures. A cabinet secretary who pledged to reduce terrorist attacks to just a few per year would not last long in the job: the only acceptable goal is zero.

Electoral politics, of course, is greatest driver of what Zenko and Cohen call “domestic threat-mongering.” In an endless contest for votes, Republicans do well by claiming to be tough in a scary world. Democrats adopt the same rhetoric in order to shield themselves from political attacks. Both sides see an advantage in a politically risk-averse strategy. If a minor threat today turns into a sizeable one tomorrow, better to have sounded the alarm early than to have appeared naïve or feckless.

But Zenko and Cohen make the politically uncomfortable argument that it’s wrong to govern based on the prospect of unlikely but extreme events. Instead of marshalling our resources for the 1 percent risk of a nuclear jihadist, as Vice President Dick Cheney argued we should, we should really set our security policy based on the 99 percent of the time when things go America’s way.

They point to the number of wars between major states and the number of people killed in wars every year, both of which have been steadily declining for decades. They also point to the historical, systematic growth of the global economy and spread of financial and trade links, which have undergirded an unprecedented period of peace among rival great powers and within the West.

Their thinking follows in the footsteps of a small but persistent group of contrarian security scholars, who have noted the post-9/11 spike in America’s already long history of threat exaggeration. Best known among them is Ohio State University political scientist John Mueller, who has argued that American alarmism about terrorism can cause more harm to our well-being and national economy than terrorism itself. In that vein, Zenko and Cohen claim that America’s over-militarization prompts avoidable wars and has in fact created far more problems than it solves, from terrorist blowback to huge drains on the Treasury.

The implications, as they see it, are clear: spend less money on the military; spend more on the boring, international initiatives that actually make America safe and powerful. Zenko’s favorite example is loose nukes, which pose hardly any threat today but were a real cause for concern as the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, leaving poorly secured weapons across an entire hemisphere.

“There was a solution: limit nuclear stockpiles and secure them,” Zenko says. “We took common-sense steps, none of which involved the US military. We send contractors to these facilities in Russia, and they say ‘The fence doesn’t work, the cameras don’t work, the guards are drunk.’ It’s cheap, and it works. This is what keeps us safe.”

Not everyone agrees. Robert Kagan, the most influential proponent of robust American power, argues that America is safe today precisely because it throws its military might around. President Obama said he relied for his most recent state of the union address on Kagan’s newest book, “The World America Made.” Mackenzie Eaglen, a defense expert at the American Enterprise Institute, says America benefits even when it appears to overreact. According to this thinking, even if the Pentagon designs the military for improbable threats and deploys at the drop of the hat, it is performing a service keeping the world stable and deterring would-be rivals. Like most establishment defense thinkers, Eaglen believes American dominance could easily and quickly come to an end without this kind of power projection.

“Power abhors a vacuum,” she says. “If we don’t fill it, others will, and we won’t like what that looks like.”

Other critics of Zenko and Cohen’s argument, like defense policy writer Carl Prine, say the comforting data about declining wars and violent deaths is misleading. Today’s circumstances, they argue, don’t preclude something drastic happening next — say, if China, or even a rising power like Brazil, veers into an unpredictably bellicose path and clashes violently with American interests. Simply put, safe today doesn’t mean safe tomorrow.

Even if Zenko and Cohen are right, however, and the big-military crowd is wrong, it is nearly impossible to imagine a spirit of “threat deflation” taking hold in American politics. The already alarmist expert community that shapes US government thinking was further electrified by 9/11. Anyone in either party who argues for a leaner military, or pruning back intelligence infrastructure, risks being portrayed as inviting another attack on the homeland. The result is an unshakeable institutional inertia.

To get a sense of what they’re up against, listen to James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, presenting the “Worldwide Threat Assessment” to Congress, as his office does every year. The latest version, in January this year, reads like a catalogue of nightmares, describing macabre possibilities ranging from Hezbollah sleeper cells attacking inside America to a cyberattack that could turn our own infrastructure into murderous drones. Are these science fiction visions, or simply the wise man’s anticipation of the next war? It’s impossible to know, but one thing is striking: there’s no attempt in the intelligence czar’s report to rank the threats or assess their real likelihood. He simply and clinically presents every possible, terrifying thing that could happen, and signs off. It’s truly frightening reading.

This is what Zenko dismissively deems the “threat smorgasbord.” It makes clear how high the stakes are in planning for war and terrorist attacks, and how much emotional power the issue has. The reasonable thing to do might simply never be politically palatable. The current debate about Iran’s nuclear intentions is a perfect example, says Eaglen, who debated Cohen about his thesis on Capitol Hill in April.

“I can say Iran’s a threat, Michael can say it’s not,” she says. “But if he gets it wrong, we’re in trouble.”

Thanassis Cambanis, a fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author of “A Privilege to Die: Inside Hezbollah’s Legions and Their Endless War Against Israel” and blogs at thanassiscambanis.com. He is an Ideas columnist.

Who Is Derailing Egypt’s Transition to Democracy?

Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood presidential candidate Khairat al-Shater, who was disqualified from his campaign. Reuters

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

Many Egyptian liberals rejoiced at Tuesday’s news that three of the most polarizing — and popular — presidential candidates, including those representing the Muslim Brotherhood and the ultra-conservative Salafists, would not be allowed to compete. The final ruling from the Supreme Presidential Elections Commission followed a lower court decision a week earlier that disbanded the lopsided and widely detested constitutional convention, which had been forced through by the Muslim Brotherhood and its Salafi allies.

On the surface, the decisions about the presidential race and the constitutional convention both thwart some serious electoral shenanigans by the Muslim Brotherhood and others, but this is hardly progress for liberalism in Egypt. Unfortunately for Egypt’s prospects, both rulings came from opaque administrative bodies with questionable authority and motives. In the case of the presidential commission, there is no avenue for appeal. And in the potentially more important matter of the constitution, a decidedly political question was buried in a layer of obfuscating legalese.

No one in Egypt can explain the rules governing the two most important hinge points in Egypt’s pivot away from authoritarianism: the selection of the president and the drafting of the constitution.

Sadly, it augurs well for the ruling military junta and the increasingly bold coterie of reactionary forces in Egypt — and poorly for all the emerging political factions, from the secular revolutionaries to the most conservative Islamists.

It’s not just that liberal, short-term gains came through illiberal means. It’s that the pair of game-changing decisions call into question what forces, if any, have control over political life in Egypt.

Events are moving so fast that even seasoned Egyptian activists are still spinning. Presidential candidates put themselves forward on April 6. The frontrunners were all controversial: Hazem Salah Abou Ismail, a charismatic Salafi preacher who has criticized military rule but also embraced extreme, at times conspiratorial, political views and wants to implement Islamic law; Khairat Shater, the most powerful man in the Muslim Brotherhood, who broke his own promise that his group would not have a candidate; and Omar Suleiman, the Hosni Mubarak regime’s spy chief, who reversed himself at the last minute and entered the race with the active support of the reconstituted intelligence services.

The presidential election commission invalided ten candidates, including these three front-runners, on technicalities. Sheikh Hazem fell afoul of a rule that he originally supported, thinking it would hurt secular liberals; he was disqualified because his mother — like millions of Egyptians — had taken a second, in this case American, passport. Shater was banned because he served prison time under Mubarak’s rule; he had been convicted of fraud by a military court, almost certainly a fabricated case that was part of the ancien regime witch hunt against the Brotherhood. Suleiman, whose candidacy had caused the most alarm among liberals and Islamists alike, was kicked off the ballot because some of the petition signatures he collected were deemed fraudulent.

The first ruling technically was consistent with regulations, which themselves are a disturbing sign of the nationalist chauvinism ripening in Egypt. The second two sound like trumped-up technicalities, even if their immediate impact is to calm Egypt by removing divisive candidates from the race. Suleiman’s exit is undeniably good for Egypt, but there was a more legitimate process underway in parliament to exclude his candidacy on the merits, because of his prior role as Mubarak’s henchman and vice president. Alleging forged signatures was a signature old regime trick to discredit opponents such as Ayman Nour after he challenged Mubarak for the presidency in 2005.

In Shater’s case, the military regime had issued a pardon for the trumped-up old conviction. One vestige of the old regime, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, gave Shater the green light; another carryover, the elections bureaucracy, vetoed it.

Meanwhile, the constitution-writing farce ground to a halt last week, on April 10, when it was invalidated by the Supreme Administrative Court, a lower court subject to appeal. The Brotherhood and the Salafis had packed the Constituent Assembly with a veto-proof majority of its own members. According to its founding rules (which were dictatorially issued by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces last year), the constitutional committee was supposed to broadly represent Egyptian society. Instead, it was an Islamist monolith, alienating virtually every other imaginable constituency, from the establishment clerics of Al Azhar and the Coptic Church to women, workers, peasants, liberals, and nationalists. Egypt’s many constitutional and legal scholars were notably absent.

A boycott had already weakened the Assembly, which lost legitimacy with all but the staunchest supporters of the Brotherhood and the Salafi Noor Party. But it was dissolved on a technicality. According to the court, the Islamists in parliament aren’t allowed to appoint themselves to write the constitution. The court said the Brotherhood had broken the rules — which is odd, given that the Brotherhood had followed the constitutional process to the letter even while abnegating its spirit.

The ruling leaves the Brotherhood free to appoint another, equally imbalanced and illegitimate assembly, so long as its members are Islamists not already sitting in parliament. The fundamental problem remains — the Brotherhood is able, and appears willing, to behave in the same authoritarian manner as Mubarak’s regime.

What’s really going on here? Who decided to disqualify three presidential front-runners? Who shut down the constitutional process that had been convened, however poorly, by the freely and fairly elected parliament? On what grounds?

In both instances, a group of essentially anonymous and unaccountable bureaucrats radically transformed the political landscape, citing reasons at best opaque and at worst nonsensical, deploying jargon and legalese to set the parameters of Egypt’s future state.

We have no idea, really, who these officials are, whose interests they serve, whether they are acting in good faith, as independent decision-makers, or at someone else’s behest. It’s a replay of the way major decisions were made in Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt, with a charade of faceless government cogs announcing policies rooted in a complex hierarchy of laws while the all-powerful president claimed complete and impartial detachment.

This is what Issandr El Amrani at the Arabist calls “lawfare” in the Egyptian context, and it extends a nefarious precedent, cultivated during decades of dictatorship. From 1954 to 2011, civilians ruled Egypt under a nominally liberal constitution; in practice, those civilian presidents were retired generals who exercised absolute authority through the military and police, all the while ignoring the constitution on the pretext of a decades-long “state of emergency.”

Today it’s a different, more complicated story; there’s evidence that more players than the ruling military junta have a role in these behind-the-scenes decisions. The next two months are crucial. Presidential elections are to begin May 23 and conclude June 17. Field Marshal and acting president Mohamed Hussein Tantawi suggested this week that a constitution must be written in a hurry, before a new chief executive takes over at the end of June. Procedurally, that’s a near-impossibility. A year and a half of posturing and maneuvering will play out in this final stage, when the old and new power players in Egypt will fight for control of the next phase.

The way this election and constitution-writing process is playing out will at best cast a pall over the transition and, at worst, presage a return to outright authoritarian military rule.

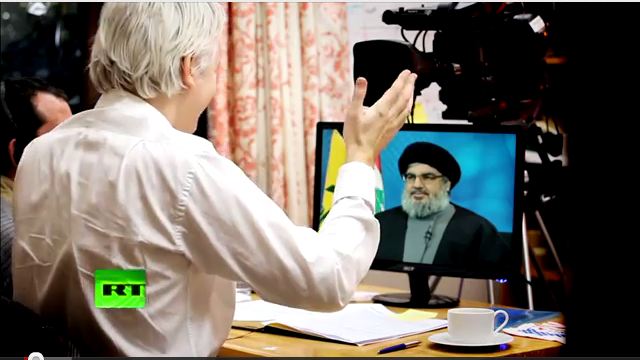

Who is the Father of the Chicken?

Julian Assange’s interview with Hassan Nasrallah told us nothing new about Hezbollah, but it was interesting all the same for the very fact that it took place. Since 2006, Nasrallah has only spoken to one other Western reporter (Seymour Hersh of The New Yorker), and Hezbollah has minimized its contact with the Western media. The Party of God’s position effectively has been that it’s simply a waste of its time and resources to talk to an audience that views it as a bunch of recalcitrant terrorists under any circumstances.

Perhaps Nasrallah calculated that he stood to benefit from a direct address to a Western audience, what with Syria’s government teetering and Hezbollah situated no longer as a defiant underdog but as a status quo power in a transforming Arab world. Or maybe he just felt like he owed a karmic favor to the Father of Wikileaks and his new patrons at the Kremlin, who are underwriting Assange’s new TV show.

Either way, Mr. Wikileaks spoke for almost a half-hour with Nasrallah, and displayed some chops. He confronted Nasrallah about Hezbollah’s inconsistency, supporting all the Arab uprisings except for the one against its sponsor in Syria. He asked point blank about reports that Nasrallah was upset about corruption and a growing taste for luxury among Hezbollah cadres – concerns I’ve heard echoed by Hezbollah partisans.

A smiling Nasrallah replied in his usual confident and measured cadence, which might have come as a surprise to a Western audience that has never has seen a full performance. Syria has always backed the resistance, he said in a simple explanation for Hezbollah’s support of Bashar Al-Assad. About the Jewish state, Nasrallah explained Hezbollah’s long-held position in gentle language: the Party of God would be satisfied if there were one single state for Israelis and Palestinians.

There were only two, small, surprises.

The first came when Nasrallah, in what was either a display of humor or an unwitting security lapse, revealed some of the code words favored by Hezbollah’s fighters: “donkey,” “cooking pot,” and most intriguingly, “the father of the chicken.”

“No Israeli intelligence agent or computer agent is going to understand what the father of the chicken is or why they call him the father of the chicken,” Nasrallah bragged.

Then, in order to prove his mettle to dismissive career journalists, Assange asked a real stumper of a question: if Nasrallah really considered himself a freedom fighter, why didn’t he fight against the “totalitarianism” of a monotheistic God?

Nasrallah’s clearly got a kick out of it. “How could the universe last for billions of years in such beautiful harmony if there were more than one God?” Nasrallah said with a bemused smile. “We don’t fight to impose a religious belief on anybody.”

The Lost Dream of Egyptian Pluralism

[Originally published in The Boston Globe, subscribers only.]

CAIRO — It might have seemed naïve to an outsider, but one of the great hopes among the revolutionaries who humiliated Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak more than a year ago was that the country’s strongman regime would finally yield to a democratic variety of voices. Both Islamic revolutionaries and secular liberals spoke up for modern ideas of pluralism, tolerance, and minority rights. Tahrir Square was supposed to turn the page on a half-century or more of one-party rule, and open the door to something new not just for Egypt, but for the Arab world: a genuine diversity of opinion about how a nation should govern itself.![]()

“We disagree about many things, but that is the point,” one of the protest organizers, Moaz Abdelkareem, said in February 2011, the week that Mubarak quit. “We come from many backgrounds. We can work together to dismantle the old regime and make a new Egypt.”

A year later, it is still far from clear what that new Egypt will look like. The country awaits a new constitution, and although a competitively elected parliament sat in January for the first time in contemporary Egyptian history, it is still subordinate to a secretive military regime. Like all transitions, the struggle against Egyptian authoritarianism has been messy and complex. But for those who hoped that Egypt would emerge as a beacon of tolerant, or at least diverse, politics in the Arab world, there has been one big disappointment: It’s safe to say that one early casualty of the struggle has been that spirit of pluralism.

“I do not trust the military. I do not trust the Muslim Brothers,” Abdelkareem says in an interview a year later. In the past year, he helped establish the Egyptian Current, a small liberal party that wants to bring direct democracy to Egyptian government. Despite his inclusive principles, he’s urged the dismissal from public life of major political constituencies with whom he disagrees: former regime supporters, many Islamists, old-line liberals, and supporters of the military. He shrugs: “It’s necessary, if we’re going to change.”

He’s not the only one who has left the ideal of pluralism behind. A survey of the major players in Egyptian politics yields a list of people and groups who have worked harder to shut down their opponents than to engage them. The Muslim Brotherhood — the Islamist party that is the oldest opposition group in Egypt, and the one with by far the most popular support — has run roughshod over its rivals, hoarding almost every significant procedural power in the legislature and cutting a series of exclusive deals with the ruling generals. Secular liberals, for their part, have suggested that an outright coup by secular officers would be better than a plural democracy that ended up empowering bearded fundamentalists who disagree with them.

When pressed, most will still say they want Egypt to be the birthplace of a new kind of Arab political culture — one in which differences are respected, minorities have rights, and dissent is protected. However, their behavior suggests that Egypt might have trouble escaping the more repressive patterns of its past.

***

IN A COUNTRY that had long barred any meaningful politics at all, Tahrir’s leaderless revolution begat a brief but golden moment of political pluralism. Activists across the spectrum agreed to disagree — this, it was widely believed, was the very practice that would lead Egypt from dictatorship to democracy. During the first month of maneuvering after Mubarak resigned in February 2011, Muslim Brotherhood leaders vowed to restrain their quest for political power; socialists and liberals emphasized due process and fair elections. The revolution took special pride in its unity, inclusiveness, and plethora of leaders: It included representatives of every part of society, and aspired to exclude nobody.

“Our first priority is to start rebuilding Egypt, cooperating with all groups of people: Muslims and Christians, men and women, all the political parties,” the Muslim Brotherhood’s most powerful leader, Khairat Al-Shater, told me in an interview last March, a year ago. “The first thing is to start political life in the right, democratic way.”

Within a month, however, that commitment had begun to fray. Jostling factions were quick to question the motives and patriotism of their rivals, as might be expected from political movements trying to position themselves in an unfolding power struggle. More surprising, and more dangerous, has been the tendency of important groups to seek the silencing or outright disenfranchisement of competitors.

The military sponsored a constitutional referendum in March 2011 that supposedly laid out a path to transfer power to an elected, civilian government, but which depended on provisions poorly understood by Egyptian voters. The Islamists sided with the military, helping the referendum win 77 percent of the votes, and leaving secular liberal parties feeling tricked and overpowered. The real winner turned out to be the ruling generals, who took the win as an endorsement of their primacy over all political factions. The military promptly began rewriting the rules of the transition process.

With the army now the country’s uncontested power, some leading liberal political parties entered negotiations with the generals over the summer to secure one of their primary goals — a secular state — in a most illiberal manner: a deal with the army that would preempt any future constitution written by a democratically selected assembly.

The Muslim Brotherhood responded by branding the liberals traitors and scrapping its conciliatory rhetoric. The Islamists, with huge popular support, abandoned their initial promise of political restraint and instead moved to contest all seats and seek a dominant position in the post-Mubarak order. The Brotherhood now holds 46 percent of the seats in parliament, and with the ultra-Islamist Salafists holding another 24 percent, the Brotherhood effectively controls enough of the body to shut down debate. Within the Brotherhood, Khairat Al-Shater has led a ruthless purge of members who sought internal transparency and democracy — and is now considered a front-runner to be Egypt’s next prime minister.

The army generals in charge, meanwhile, have been using state media to demonize secular democracy activists and street protesters as paid foreign agents, bent on destroying Egyptian society in the service of Israel, the United States, and other bogeymen.

Since the parliament opened deliberations in January, the rupture has been on full and sordid display. The military has sought legal censure against a liberal member of parliament, Zyad Elelaimy, because he criticized army rule. State prosecutors have gone after liberals and Islamists who have voiced controversial political positions. Islamists and military supporters have also filed lawsuits against liberal politicians and human rights activists, while the military-appointed government has mounted a legal and public relations campaign against civil society groups.

***

THE CENTRAL QUESTION for Egypt’s future is whether these increasingly intolerant tactics mean that the country’s next leaders will govern just as repressively as its last. Scholars of political transition caution that for states shedding authoritarian regimes, it can take years or decades to assess the outcome. Still, there are some hallmarks of successful transitions that Egypt appears to lack. States do better if they have an existing tradition of political dissent or pluralism to fall back on, or strong state institutions independent of the political leadership. Egypt has neither.

“Transitions are always messy, and the Egyptian one is particularly messy,” said Habib Nassar, a lawyer who directs the Middle East and North Africa program at the International Center for Transitional Justice in New York. “To be honest, I’m not sure I see any prospects of improvement for the short term. You are transitioning from dictatorship to majority rule in a country that never experienced real democracy before.”

Outside the parliament’s early sessions in January, liberal demonstrators chanted that the Muslim Brotherhood members were illegitimate “traitors.” In response, paramilitary-style Brotherhood supporters formed a human cordon that kept protesters from getting close enough to the parliament building to even be heard by their representatives.

At a rally for the revolution’s one-year anniversary in Tahrir Square, Muslim Brotherhood leaders preached and made speeches from a high stage to celebrate their triumph. It was unclear whether they were referring to the revolution, or to their party’s dominance at the polls. It was too much for the secular activists. “This is a revolution, not a party,” some chanted. “Leave, traitors, the square is ours not yours,” sang others.

Hundreds of burly brothers linked arms, while a leader with a microphone seemed to taunt the crowd. “You can’t make us leave,” he said. “We are the real revolution.” In response, outraged members of the secular audience tore apart the Brotherhood’s sound system and pelted the stage with water bottles, corn cobs, rocks, even shards of glass.

The Arab world is watching closely to see what happens in the next several months, when Egypt will write a new constitution and elect a president in a truly competitive ballot, and the military will cede power, at least formally. Even in the worst-case scenario, it’s worth remembering that Egypt’s next government will be radically more representative than Mubarak’s Pharaonic police state.

Sadly, though, political discourse over the last year has devolved into something that looks more like a brawl than a negotiation. If it continues, the constitution drafting process could end up more ugly than inspiring. The shape of the new order will emerge from a struggle among the Islamists, the secular liberals, and the military — all of whom, it now appears, remain hostage to the culture of the regime they worked so hard to overthrow.

The Things Anthony Shadid Taught Me

Anthony at home in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his son and friends.

Anthony Shadid never seemed to be in a hurry. If you needed him, or simply wanted his company, he would linger to chat and fix you with a gaze that defined undivided attention. He gave the impression that nothing was more important to him than whomever he happened to be speaking to, even if he had a dozen deadlines. His hospitable nature blended seamlessly with Levantine mores, but I think it originated in equal measure from his origins in Lebanon, in Oklahoma, and in his entirely exceptional soul.

Often, I was scared when I was with Anthony. He reassured in the most primal manner, by example. The day after Saddam Hussein fled Baghdad, hundreds of journalists, Iraqi fortune seekers, and U.S. Marines thronged the front lot of the Palestine Hotel. In a panic, I found Anthony in his room upstairs, surrounded by stacks of bottled water. “You have time for a coffee?” he inquired, as if I were the busy one, as if time were limitless. Around him, in a way, it was. The more he slowed things down in the minute, the more minutes he seemed to pack into a day. He connected with so many of us — artists, political activists, militiamen, families, working people, fellow journalists, heads of state — and each of us felt that we had shared something alone with Anthony. And we had. That bounty was one of his many gifts.

On Christmas eve in 2003, we drove into Baghdad together. His first marriage was failing, and he spent that long night in Iraq’s western desert speaking of his daughter, Laila, and of the Iraq story, both of which he loved in different ways. He felt ineluctably that he could not leave that story at a crucial time. It was a commitment shouldered without arrogance but with a clear — and in my opinion, correct — assessment that if he didn’t tell the stories he was telling, no one would.

That commitment awed and inspired us all. Readers saw it in his dispatches from Iraq over more than a decade. Colleagues saw it in Iraq, Lebanon, the West Bank, Libya, and countless other places. He was devoted to better coverage of the Arab world. He lived that devotion in his own writing, about which nothing need be said because it so authoritatively speaks for itself, but also in the countless invisible acts he did to make the work of others better. He shared contacts with novice reporters he just had met. He took hours to mentor strangers and friends alike, about brief dispatches or sprawling book projects. He was the least selfish reporter I ever met, and he was the one who had the most to share, which he did compulsively.

I am not alone when I say I wanted to be more like Anthony Shadid, in my approach to people, to stories, to the region that was his destiny and which became my own focus. The people he wrote about were never subjects. They each were a world, in which he became engrossed for the entirety of the length of his relationship to them, whether it lasted an hour or a year. In Iraq, he taught me history. In Lebanon, as we criss-crossed the front lines in the 2006 war, he showed me what courage looks like. I drove him around the border, where he translated the conversations we had with people. At one point, alone on an exposed ridge, we heard a steady patter of mortar shells, each one closer to us than the next. We realized we weren’t approaching somebody else’s front line; we alone were the targets. “What do you think?” he said, unhurriedly. “Should we go?” I answered by running back to the car. Anthony, as always, was full of grace.

We all know how he brought that grace to the stories of people at war and in revolt across the Arab world. Soon, when the book he had labored over for half a decade is released next month, we might learn how he applied that delicacy to the tale of his ancestral home in Marjayoun. He lovingly rebuilt the manse on a hill overlooking the Hula Valley, and in the process fell in love anew with his wife Nada. With Marjayoun and Nada, Anthony opened a new chapter in happiness, which blossomed on his face when he was with them or with his daughter Laila.

With same mix of humility, inquisitiveness and contagious enthusiasm, he invited me to join him at one of his first olive harvests. We carted the fruit of his two trees to a next-door village, and peered like little boys into the turbines that crushed them into oil. He carried the blue plastic vats of oil over the threshold of his stone house grinning like a groom.

I can’t begin to enumerate the lessons I learned from Anthony. Over whiskey after 18-hour days covering the war in south Lebanon, he taught me to dump my notebooks every day, no matter how tired I was. With his children, he taught me to appreciate the majesty and wonder of a small person growing up. He outlined before he wrote, and then poured out the words in one fluid swoop. He almost always seemed delighted by what he was doing. We teased him and honored him through affairs like the Anthony Shadid contest, in which friends tried to top one another with ever-more absurd Shadidian turns of phrase that piled history upon olfactory sensation upon narrative upon character. When we tried it, it was an uproarious joke. When Shadid did it, it was poetry.

In September, on his last birthday, we shared a sheesha at a garden in Cairo. He knew he shouldn’t smoke because of his asthma, but he felt it was a forgivable peccadillo. He was frustrated to be away from Nada and his children, and he was struggling to untangle the web of commitments to which he felt utterly and indivisibly attached: his family, the Arab revolts, his writing, his desire to engage the American public through the pages of a daily newspaper, the platform he believed was the most relevant. He talked about finding some way to slow down, to fulfill all his missions at once. Perhaps, he dreamed, he could balance it all better as a foreign affairs columnist. Those of us who knew Anthony well knew that whatever he did, he would never slow down, whether he was restoring a stone house or covering a war.

He had fears too, but they were less prosaic. He was afraid of not being a good enough husband or father, and he was afraid of letting down the people about whom he wrote. He was afraid that he worked too much, but he also feared what might happen if he worked less. Like any experienced gambler, he knew how to stay calm at the blackjack table, or on deadline, or under fire, but he also carried a knot of anxiety. I had no other friend like him, and no other mentor. In his family, all the more, Anthony will leave an incomprehensible hole. I’m not sure what comfort it brings to remember that his death is a uniquely shared tragedy. It is said about many, but in the case of Anthony Shadid it is bitterly true, that the world is poorer for his passing. We will all be dumber without his stories. There is no one else who can do what he did. Many will continue to try, however, and we can consider that one of Anthony’s last bequests.

This article available online at:

http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/02/the-things-that-anthony-shadid-taught-me/253254/

The Lonely Superpower

[Read the original piece in The Boston Globe (subscription required).]

After decades of nuclear brinkmanship, Americans felt profound relief when the Cold War ended. The Soviet Union’s collapse in 1989 transformed the world almost overnight from a battleground between two global giants — a bipolar world, in scholarly parlance — to a unipolar world, in which the United States outstripped all other powers.

In foreign policy circles, it was taken for granted that this dominance was good for America. Experts merely differed over how long the “unipolar moment” could last, or how big a peace dividend America could expect. Some even argued that the end of the arms race between Moscow and Washington had eliminated the threat of world war.

Now, however, with a few decades of experience to study, a young international relations theorist at Yale University has proposed a provocative new view: American dominance has destabilized the world in new ways, and the United States is no better off in the wake of the Cold War. In fact, he says, a world with a single superpower and a crowded second tier of distant competitors encourages, rather than discourages, violent conflict–not just among the also-rans, but even involving the single great power itself.

In a paper that appeared in the most recent issue of the influential journal International Security, political scientist Nuno P. Monteiro lays out his case. America, he points out, has been at war for 13 of the 22 years since the end of the Cold War, about double the proportion of time it spent at war during the previous two centuries. “I’m trying to debunk the idea that a world with one great power is better,” he said in an interview. “If you don’t have one problem, you have another.”

Sure, Monteiro says, the risk of apocalyptic war has decreased, since there’s no military equal to America’s that could engage it in mutually assured destruction. But, he argues, the lethal, expensive wars in the Persian Gulf, the Balkans, and Afghanistan have proved a major drain on the country.

Even worse, Monteiro claims, America’s position as a dominant power, unbalanced by any other alpha states actually exacerbates dangerous tensions rather than relieving them. Prickly states that Monteiro calls “recalcitrant minor powers” (think Iran, North Korea, and Pakistan), whose interests or regime types clash with the lone superpower, will have an incentive to provoke a conflict. Even if they are likely to lose, the fight may be worth it, since concession will mean defeat as well. This is the logic by which North Korea and Pakistan both acquired nuclear weapons, even during the era of American global dominance, and by which Iraq and Afghanistan preferred to fight rather than surrender to invading Americans.

Of course, few Americans long for the old days of an arms race, possible nuclear war, and the threat of Soviet troops and missiles pointed at America and its allies. Fans of unipolarity in the foreign policy world think that the advantages of being the sole superpower far outweigh the drawbacks — a few regional conflicts and insurgencies are a fair price to pay for eliminating the threat of global war.

DAVID FLAHERTY FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

But Monteiro says that critics exaggerate the distinctions between the wars of today and yesteryear, and many top thinkers in the world of security policy are finding his argument persuasive. If he’s right, it means that the most optimistic version of the post-Cold War era — a “pax Americana” in which the surviving superpower can genuinely enjoy its ascendancy — was always illusory. In the short term, a dominant United States should expect an endless slate of violent challenges from weak powers. And in the longer term, it means that Washington shouldn’t worry too much about rising powers like China or Russia or the European Union; America might even be better off with a rival powerful enough to provide a balance. You could call it the curse of plenty: Too much power attracts countless challenges, whereas a world in which power is split among several superstates might just offer a paradoxical stability.

From the 1700s until the end of World War II in 1945, an array of superpowers competed for global influence in a multipolar world, including imperial Germany and Japan, Russia, Great Britain, and after a time, the United States. The world was an unstable place, prone to wars minor and major.

The Cold War era was far more stable, with only two pretenders to global power. It was, however, an age of anxiety. The threat of nuclear Armageddon hung over the world. Showdowns in Berlin and Cuba brought America and the Soviet Union to the brink, and the threat of nuclear escalation hung over every other superpower crisis. Generations of Americans and Soviets grew up practicing survival drills; for them, the nightmare scenario of thermonuclear winter was frighteningly plausible.

It was also an age of violent regional conflicts. Conflagrations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America spiraled into drawn out, lethal wars, with the superpowers investing in local proxies (think of Angola and Nicaragua as well as Korea and Vietnam). On the one hand, superpower involvement often made local conflicts far deadlier and longer than they would have been otherwise. On the other, the balance between the United States and the USSR reduced the likelihood of world war and kept the fighting below the nuclear threshold. By tacit understanding, the two powers had an interest in keeping such conflicts contained.

When the Soviet Union began its collapse in 1989, the United States was the last man standing, wielding a level of global dominance that had been unknown before in modern history. Policy makers and thinkers almost universally agreed that dominance would be a good thing, at least for America: It removed the threat of superpower war, and lesser powers would presumably choose to concede to American desires rather than provoke a regional war they were bound to lose.

That is what the 1991 Gulf War was about: establishing the new rules of a unipolar world. Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, Monteiro believes, because he miscalculated what the United States was willing to accept. After meeting Saddam with overwhelming force, America expected that the rest of the world would capitulate to its demands with much less fuss.

Monteiro compared the conflicts of the multipolar 18th century to those of the Cold War and current unipolar moment. What he found is that the unipolar world isn’t necessarily better than what preceded it, either for the United States or for the rest of the world. It might even be worse. “Uncertainty increases in unipolarity,” Monteiro says. “If another great power were around, we wouldn’t be able to get involved in all these wars.”

In the unipolar period, a growing class of minor powers has provoked the United States, willing to engage in brinkmanship up to and including violent conflict. Look no further than Iran’s recent threats to close the Strait of Hormuz to oil shipping and to strike the American Navy. Naturally, Iran wouldn’t be able to win such a showdown. But Iran knows well that the United States wants to avoid the significant costs of a war, and might back down in a confrontation, thereby rewarding Iran’s aggressive gambits. And if (or once) Iran crosses the nuclear threshold, it will have an even greater capacity to deter the United States. During the Cold War, on the other hand, regional powers tended to rely on their patron’s nuclear umbrella rather than seeking nukes of their own, and would have had no incentive to defy the United States by developing them.

Absent a rival superpower to check its reach, the United States has felt unrestrained, and at times even obligated, to intervene as a global police officer or arbiter of international norms against crimes such as genocide. Time and again in the post-Cold War age, minor countries that were supposed to meekly fall in line with American imperatives instead defied them, drawing America into conflicts in the Balkans, Somalia, Haiti, Iraq, and Afghanistan. This wasn’t what was supposed to happen: The world was supposed to be much safer for a unipolar superpower, not more costly and hazardous.

Not everyone agrees that the United States would benefit from having a major rival. The best-known academic authority on American unipolarity, Dartmouth College political scientist William C. Wohlforth, argues that it’s still far better to be alone at the top. Overall, Wohlforth says, America spends less of its budget on defense than during the Cold War, and fewer Americans are killed in the conflicts in which it does engage. “Those who wish to have a peer competitor back are mistaken,” he said. “They forget the huge interventions of the Cold War.”

Between 1945 and 1989, Wohlforth says, proxy wars between America and the Soviet Union killed hundreds of thousands of people, against the backdrop of a very real and terrifying threat of nuclear annihilation. Today, he says, the world is still dangerous, but it’s much less deadly and frightening than it was in the time of the nuclear arms race.

For his part, Monteiro agrees that the Cold War was nasty and scary; he just wants to debunk the notion that what came next was any better. According to Monteiro, bipolarity and unipolarity pose different kinds of dangers, but are equally problematic.

Accepting this theory would have stark implications. For one thing, it would mean that America shouldn’t be afraid of emerging superpowers. In a unipolar world, America faces the temptation to overextend itself, perhaps wasting its resources in conflicts like Iraq and Afghanistan rather than protecting its core national interests; having another superpower to contend with could change that focus. “It’s not a bad thing to have a peer competitor,” Monteiro says.

His analysis suggests that the one way the United States can reduce its involvement in costly conflict is to shift its strategy from what he calls “global dominance” to “disengagement,” a posture in which America would keep out of regional conflicts and let minor powers fight each other. The one thing that might restrain a problem state like Iran or North Korea, according to Monteiro, is an assurance that the United States won’t seek to overthrow their regime.

The debate has direct bearing on a question that increasingly preoccupies policy makers in Washington: How should the United States respond to China’s rising power? Conventional wisdom, with its aversion to a bipolar or multipolar world, would counsel the United States to do all it can to forestall or even thwart China’s ascension to superpower status. By Monteiro’s logic, however, America should consider China’s rise a potential boon, something to be managed with an eye toward minimizing friction. “We might not like it, but in many ways China’s rise is not very dangerous,” says Charles Glaser, an influential political scientist at The George Washington University who also writes about unipolarity, and who shares much of Monteiro’s skepticism about its benefits.

Monteiro’s most radical insight concerns what he considers the dim likelihood of stability in a world where the United States is dominant. “Regardless of US strategy, conflict will abound,” Monteiro writes. What does lie in America’s control, he argues, is the choice between laboring to extend that dominance or merely maintaining an edge while disengaging from most conflicts. If America continues to involve itself in the constant ebb and flow of regional wars, as it has during two decades as unipolar giant and global police officer, it will exhaust its treasury and military resources, and feel threatened when rising powers like China approach parity. If, on the other hand, it chooses to disengage, it can husband its military might for the more important task of facing the new superpowers that inevitably will emerge.

Ashraf Khalil and Wael Ghonim Write the Egyptian Revolution

My review of the two latest Egypt revolution books is up at The Daily Beast. I discuss Wael Ghonim’s memoir and Ashraf Khalil’s reported book about the uprising.

Two books released this month can help us start to make sense of this puzzle, with detailed accounts of the uprising a year ago and some insight into the institutions and attitudes that shape Egypt’s largely conservative society.

The first is a memoir by Wael Ghonim, the celebrated Google executive who helped spark the uprising with a wildly popular Facebook page dedicated to a middle-class kid beaten to death by the police. Ghonim tapped into a demographic that proved crucial to the Egyptian uprising: upwardly mobile college-educated youth frustrated by Egypt’s stagnation but wary of politics and activism.

As he tells his own story, Ghonim is a driven, socially awkward young man—ambitious but almost allergic to fame. His early clandestine ventures online revolve around building a library of religious recordings called IslamWay.com. He’s offered great sums of money but instead quietly donates it to charity, all while he’s still a teenager. In the years around 9/11, he marries and pursues his dream, which has nothing to do with unseating Mubarak’s tyrannical police regime. No, young Wael wants nothing more than to work at Google, a goal he finally achieves in 2008.

…

For a broader look at Egypt’s transformation, one can turn to journalist Ashraf Khalil’s Liberation Square: Inside the Egyptian Revolution and the Rebirth of a Nation. Khalil’s illuminating reporting situates the revolt in the stultifying decades that preceded it. (I should mention that Khalil is a friend dating back to the days when we were both based in Baghdad.) He spends nearly half his story on the final decades of Mubarak’s crony rule, detailing the pompous ineptitude of the aging dictator with eternally young hair. And he does an admirable job pulling together the threads of the early dissident and activist efforts rooted in the late 1990s.

By the time Khalil gets to the demonstrations of Jan. 25, 2011, we understand why some Egyptians felt they could no longer “walk next to the wall,” as the proverb instructs, and felt they might as well risk death or imprisonment rather than submit to Mubarak’s capricious police state. But we share the wonder of Khalil, and many of the activists he interviews, who even as they promoted an uprising doubted that Egyptians would join them in significant numbers.

The Despair of Egypt

[Read the original post in The Atlantic.]

The state of the revolution in Egypt is today, for me and probably many others watching it closely, cause for rage and despair. The case for despair is obvious: the dumb, brute hydra of a regime has dialed up its violent answer to the popular request for justice and accountability, and has expanded its power. The matter of rage is more complicated: in Egypt, Tunisia, and other Arab countries, it was righteous anger — forcefully but strategically deployed — that brought fearsome police states to their knees. The outrages of Egypt’s regime are still on shameless display. The only question is whether the fury they provoke will make a difference.

When we see the Egyptian soldier enthusiastically stripping a female protester while another kicks her abdomen, rage is a natural response. So too when we see soldiers and their plainclothes henchman cheerfully chuck rocks and chairs from a fifth-floor roof, and in at least one case, piss down below on their fellow Egyptians peacefully protesting in front of parliament, drawn to the streets in part because of the dozens of their comrades already killed by the state. Most enraging of all is the self-righteous, imperious lying that accompanies the industrial-scale state abuse of its citizens. General Adel Emara hectored the Egyptian reporters who tried to question him about last week’s outrages in Tahrir Square, including the blue bra sequence.

Like the American generals in the early years of the Iraq occupation who complained that the nay-saying media was telling mean, inaccurate stories about their swimming success, Emara blamed the media. The Supreme Council for the Armed Forces was protecting the nation and the demonstrators downtown were spreading chaos. “The military council has always warned against the abuse of freedom,” he said, apparently without irony. In statements this week, the military has incredibly claimed that the bands of hundreds or thousands of unarmed protesters are actually a plot to overthrow the state — a grotesque reversal of the truth.

The new prime minister, Kamal Ganzouri, blamed the “counter-revolution” and “foreign elements” for the demonstrations. He also promised no violence would be used against them, even as security forces shot more than a dozen people and beat hundreds of others. No shame here, but perhaps some ulterior plan to discredit protest entirely. An angry response might be the only one possible, the only way potentially to thwart this colossus. Remember the original protests a year ago in Tunisia and Egypt: people billed them as “Days of Rage.”

Why the violence against demonstrators, against women, against foreigners? Apparently the SCAF believes it can intimidate people into submission, that it can succeed where its authoritarian predecessor Hosni Mubarak failed. The death tolls of this year, and the arrest of 13,000 civilians brought before military trial, are measures of the repressive reflexes of the current military rulers. On November 19, police set upon a small group that had camped out on the edge of Tahrir Square, beating them and destroying their tents — and sparking two weeks of street battles that left at least 40 dead and 2,000 wounded. More recently, on December 16 security forces attacked a follow-on protest in front of the parliament building and the ongoing fighting has killed at least 16 people and critically wounded hundreds.

There are few plausible explanations for the recent spasms of violence against nonviolent demonstrators. It’s hard to imagine why state security attacks civilians during periods of calm, sparking new protests and reinvigorating the revolutionary movement. Perhaps the military has a strategy designed to discredit protesters and revolutionary youth, allowing or even engineering street violence which they can then use in the state media to portray activists as hooligans. Or, perhaps, the police and common soldiers have developed such an intense hatred for the demonstrators — who let us remember, succeeded at putting the security establishment on the defensive for the first time in 60 years — that whenever they confront a protest their tempers flare and they lash out.

There’s also a theory that the police, and even some parts of the army, are simply in mutiny, disregarding the SCAF’s orders. Some believe that the SCAF genuinely believes that all protesters are saboteurs, foreign agents, and traitors out to gut the Egyptian state. Some also suggest that the SCAF is simply incompetent, and that each sordid episode of protest, massacre, political agreement, and betrayal is an act in a bumbling melodrama starring a cast of senescent, befuddled generals, most of whom lived their glory days in military study abroad programs in Brezhnev’s Moscow.

Whether there’s a plan or no plan, some of the results are becoming clear. The Muslim Brothers and the Salafis, who dominated the election results so far, have essentially supported the SCAF’s vague schedule to transfer power to a civilian president by summer. Liberals have coalesced around a new demand for a president to be elected immediately and take over by February 11, the one-year anniversary of Mubarak’s resignation. The SCAF has continued its divide and conquer tactics, undermining all dissent in public while meeting in private with politicians from all parties.

All power still rests in the hands of the military, which has designed an incomprehensible transition process clearly engineered to exhaust any revolutionary or reformist movement. (Before Egypt can have a new government with full powers, the military believes there must be a referendum, two elections of three rounds each for a legislature, another referendum on a constitution, and then a presidential election. That doesn’t include runoffs and do-overs.)

Meanwhile there’s a debate underway about who “lost” the revolution, as if the demonstrators and liberal Egyptians could have gotten it right and changed Egypt over the last 12 months. Steven Cook partly blames the protesters for “narcissism” and “navel-gazing,” claiming they lost the opportunity to engage the public because they were too busy on Facebook and Twitter. Marc Lynch writes that the protesters have not captured the imagination of the wider public, though he (correctly) holds the SCAF responsible for bungling the transition so far.

Perhaps the most depressing read this week is a dark and self-critical essay by the revolutionary, blogger, and failed parliamentary candidate Mahmoud Salem, better known by his blog pseudonym Sandmonkey. He now believes that he and his fellow revolutionaries blew a chance to connect with Egyptians during the brief, hopeful moment after Mubarak quit; that, Salem argues, is when people were willing to change. Now that moment of possibility has evaporated.

One common thread runs through these writings, and through much of the critique of the uprising: that the revolutionaries never bothered to try to reach “the people.” There is some truth to that claim. Some of the most talented organizers among the original January 25 revolutionaries quickly turned their focus to party politics. Their efforts might bear fruit within one or two election cycles — five to ten years — but theirs is a dreary and inside job of crafting party platforms, opening branch offices, and recruiting staff and members. Another crucial cadre of revolutionaries were radical by conviction; it was by design, and not by accident, that they invested their energy in street protests and in forging links with labor activists, in order to spread the revolution into the workforce. That’s not to say that the remainder, who number at best a few thousand, didn’t try to engage the Egyptian public; they’ve been trying, but they haven’t been too successful. They go on television, they write newspaper columns, they hold press conferences. In August and September, they put on Revolutionary Youth Coalition road shows, where they went to towns and neighborhoods across Egypt to explain the goals of the protests. Even without a budget, however, they could have done that kind of outreach, in cafes and poor neighborhoods, every week since February 11; instead, much of their time was tied up in Tahrir protests whose utility made less and less sense even to sympathetic Egyptians.

The revolutionary youth alone hold promise for Egypt’s politics of accountability, rule of law, minority rights, and civilian control over the army — the unpopular but important bulwarks of a more liberal order. It would be a mistake to focus too much on public opinion of the protests, or even the gatherings’ size. What matters is their impact. The military, in fact, has set the parameters. Since February, they have scorned those who negotiate with them in good faith at polite meetings. The only concessions the generals have made — including, last month, their agreement to schedule presidential elections a year and a half earlier than they’d originally wanted — came as the result of violent protests in Tahrir Square. Perhaps the revolutionaries found it simple to flood Tahrir in response to every crisis; but it was the generals who taught them that protest was the only tool that actually worked.

So when it comes to blame, save it for the military, the actor driving events and the sole authority responsible for Egypt. The act, now ragged, has the generals pretending to be reluctant rulers, eager to hand over the keys if only a responsible captain would materialize to steer the ship of state. The rest of the players in Egypt merit mere disappointment: the mediocre politicians; the Muslim Brothers who repeatedly passed up the opportunity to take a moral, national position rather than defend their narrow institutional self-interest; the activists who failed to weave a national culture movement in the aftermath of January 25; the Egyptian elites who didn’t invest their money and influence in revolutionary causes; the civil servants and state institutions that slavishly serve whoever is in power; and Washington, which has utterly failed to persuade its billion-dollar welfare ward, the SCAF, to behave responsibly.

Is Egypt’s revolution dead, beguiled by its own hype, endlessly occupying and fighting over meaningless patches of pavement while the rest of the country forgets about their utopian aims? “Symbols are nice, but they don’t solve anything,” Mahmoud Salem writes. “There is a disconnect between the revolutionaries and the people. … Our priorities are a civilian government, the end of corruption, the reform of the police, judiciary, state media and the military, while their priorities are living in peace and putting food on the table.”

Can persistent revolt eventually beget genuine revolution, like wind carving a valley through granite? I’m of two minds. The women’s marches this week fill me with hope. With determination and creativity, Egyptian women flooded the streets to shame their oppressors and reclaim the righteous narrative fraudulently hijacked by the SCAF. “Egypt’s women are a red line,” they chanted, and for once, the SCAF issued a formal apology. But another recent encounter, a private one, fills me with despair. A man I’ve known for some time, who used to work in the tourist trade and whose financial well-being teeters precariously between Spartan and destitute, confided in me that he saw only one option to provide for his children in the new Egypt: to rob an armored truck. At first I thought he was kidding, but he was not. “Don’t worry,” he assured me. “I have a plan. No one will get hurt. The bank can afford to lose the money. I will be able to be strong again for my children.”

I hope I dissuaded him, but for my friend and presumably many like him, this year of political turbulence has been more terrifying than inspiring, for reasons only tenuously connected to the SCAF’s abuses, the missed opportunity for a cultural revolution, or the birth of a new Arab politics. The junta’s propaganda habitually describes critics as unpatriotic, counter-revolutionary, or “not Egyptian,” eager to present a uniform mold of the “true Egyptian.” On the contrary, however, the proud marching women and the marauding soldiers are all Egyptian, just like the perplexed revolutionaries and the would-be bank robber. All of them will be aboard for the voyage.

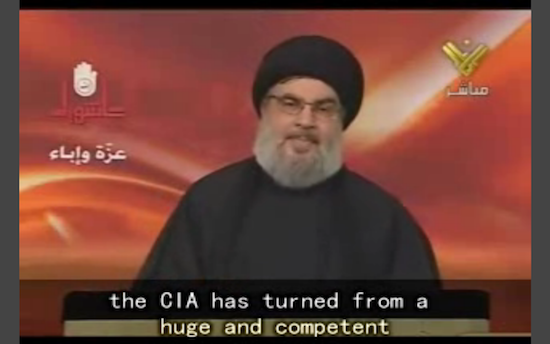

Hezbollah vs. the CIA

Throughout its history, Hezbollah has proven adept at reinventing itself in times of crisis, defying its challengers to roar back to power after appearing on the verge of marginalization and defeat.

With that caveat, it’s hard to look the current state of play in Beirut as anything but dire for Hezbollah and promising for those who would like to see a weaker “Axis of Resistance.”

Syria’s dictator is on the way out, and Hezbollah looks reactionary and out of sync with history. Hassan Nasrallah has resorted to citing the resistance record of Syria and Iran, as if the only point in their favor is that they’ve stood against Israel and the United States.

Aryn Baker, writing in Time, points out that Nasrallah feted the other uprisings in the Arab world but when it comes to Syria, has “repeated Assad’s tired canard about foreign influences (read: the U.S. and Israel) driving the revolt.”

That double standard doesn’t sit well with a new generation of Arabs who say Hizballah is doing exactly the same thing Nasrallah mocked U.S. President Barack Obama for at the beginning of the Egyptian revolution: supporting a tyrant just because of his stance on Israel. “They call themselves the party of resistance, of justice, but where is the justice?” asks Issa Hammoud, a documentary filmmaker who had been a decade-long member of Hizballah, until he left the group a few months ago in disgust over its pro-Syria policy. “By supporting Assad’s regime they are proving they have no morals.” Perhaps. But Hizballah is also demonstrating that self-interest often trumps values.

Nasrallah also has focused a lot of attention on the efforts of the CIA in Lebanon, some of which apparently have been foiled by effective Hezbollah counter-intelligence. This embarrassment for the CIA, of course, has nothing to do with Hezbollah’s legitimacy. If everyone is doing the jobs they’re supposed to be doing, America and Israel will be trying to spy on Hezbollah and Syria and Iran, and vice versa.

At a moment when Lebanese and Syrians are wondering why Nasrallah won’t put any daylight between his popular movement and Syria’s repressive minority regime, Nasrallah has used the CIA scoop as a monumental distraction.

It can’t hide his woes, which have spilled over to the domestic political arena. The Hezbollah-backed prime minister recently moved ahead to fund the Special Tribunal pursuing Hezbollah suspects in the Rafik Hariri assassination.

Mona Yacoubian argues in Foreign Affairs that Hezbollah might turn its attention to domestic politics for a period, in order to consolidate its power at home.

Others have wondered whether instability in Lebanon and Syria could prompt Hezbollah to pursue the destabilizing but legitimizing cover of regional war, but Hezbollah watchers have argued that both Hezbollah and Israel seem to want to postpone a rematch of the 2006 war that both sides are convinced will be much more destructive than the last war.

Lebanon’s political weathervane, Druze chieftain Walid Jumblatt, has distanced himself from Hezbollah’s wildly pro-Assad position (he allied with Hezbollah a few years ago after spending a few years as Hezbollah’s loudest critic). “Those who are attached to the Syrian regime should recognize that they’re being hostile to the majority of the Syrian people,” Jumblatt told Al-Majalla magazine, as reported in The Daily Star.

Still, Hezbollah boasts the most formidable militia in the Arab world, and commands the undivided loyalty of its core supporters, even if the casual fans are drifting away. For the time being, the movement also can count of Iran’s critical funding. Even in the year of the Arab uprisings, Nasrallah scored as the most popular Arab leader on the Annual Arab Public Opinion Survey (although some non-Arabs did better; Nasrallah was tied with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad and behind Turkey’s leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan).

So Hezbollah is unlikely in the short term to diminish as a player.

And Hezbollah’s unmasking of CIA agents in Lebanon serves as a stark reminder that the Party of God is a force with real tools in its arsenal, not just a rhetorically gifted leader who plays well on television. This week, Al Manar aired the name of a man it claims is the current CIA station chief in Beirut; the agency has replaced top officers in Pakistan twice in the last two years when their names were published.

However dim Hezbollah’s long-term prospects, it will remain a critical player in the short term. And if history is any indicator, it might just find a way to emerge – once again – stronger from a self-induced crisis that threatens to consign it to irrelevance.

The Inevitable Rise of Egypt’s Islamists

A veiled woman casts her vote during the second day of the parliamentary run-off elections at a polling station in Cairo. Photo: Reuters

CAIRO, Egypt — Egypt’s liberals have been apoplectic over the early results from the recent elections here. Everybody expected the Islamists to do well and for the liberals to be at a disadvantage. But nobody — perhaps with the exception of the Salafis — expected the outcome to be as lopsided as it has been so far. Exceeding all predictions, Islamists seem to be winning about two-thirds of the vote. Even more surprising, the radical and inexperienced Salafists are winning about a quarter of all votes, while the more staid and conservative Muslim Brotherhood is polling at about 40 percent.

The saga is unfolding against a political backdrop of alarmism. One can almost hear the shrill cries echoing in unison from Cairo bar-hoppers and Washington analysts: “The Islamists are coming!” In short order, they fear, the Islamists will ban alcohol, blow up the sphinx, force burqas on women, and declare war on Israel.

Before we all worry too much, however, and before fundamentalists in Egypt start to crack the champagne (in their case perhaps literally, with crowbars), it’s worth taking a look at what’s really happening with Egypt’s Islamists.

Egypt is still not a democracy, so election results mean only a little; the key players in shaping the country remain the military, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the plutocrats. To a lesser degree, revolutionary youth, liberals, and former ruling party stakeholders will have some input. The new powers-that-be in Egypt and other Arab states who are trying to break the shackles of autocracy are likely to be more religious, socially conservative, and unfriendly to the rhetoric of the United States and Israel. That doesn’t mean they’ll be warmongers, or that they’ll refuse to work with Washington, or even Jerusalem, on areas of common interest.

Islamism has been on the rise throughout the Arab and Islamic world for nearly a century and will probably set the political tone going forward. The immediate future will feature a debate among competing interpretations of Islamic politics, rather than a struggle between religious and secular parties.

Why Hezbollah Is Nervous Right Now

Photo: Matthew Cassel, Al Jazeera

Sure, Hassan Nasrallah just made his second public appearance in five years, but I’d take that less as bravado and more as a sign that Hezbollah considers its situation especially grave. Syria is teetering, and with it much of Hezbollah’s strategic depth. To boot, Hezbollah has gone so far ahead of the curve defending Bashar Assad’s regime that it has lost much of its “resistance” luster with soft sympathizers — secular Arab nationalists, Christians, Sunni Muslims, and others in Lebanon and around the Arab world who hitherto have sided with Hezbollah even if they find some aspects of The Party of God distasteful.

Hezbollah supporters have long worried that their prospects would be dim in a post-Assad Syria. I suspect that Hezbollah’s full-throated backing of Assad, in contrast to its vocal derision of other Arab tyrants, has actually made those prospects far worse. Bringing that worry into the open is Syrian opposition leader Burhan Ghalioun, who has been telling lots of reporters that when the regime falls, so too will Syria’s special relationship with Iran and Hezbollah. He tells CNN:

“The Syrian people stood completely by Hezbollah once. But today, they are surprised that Hezbollah did not return the favor and support the Syrian’s people struggle for freedom.”

Hezbollah, I think, has good reason to worry. Their days of easy access to training areas and weapons resupply are numbered.

Brian Lehrer Show

I’ve been traveling, and behind on posting. Here’s the link to last wee”s Brian Lehrer show on WNYC, with filmmaker Jehane Noujaim and me discussing the voting in Egypt.

Egypt Votes, Wary and Hopeful

Liberal candidate Basem Kamel inspects a polling station for fraud on Monday. Photo: Rolla Scolari.

(Read the original posting in The Atlantic.)

CAIRO, Egypt — Egypt took another step, albeit a conflicted one, along the trajectory it began in Tahrir Square almost ten months ago. Millions voted Monday in a parliamentary election marred by the ham-handed meddling of the ruling military junta, but with almost none of the widespread violence and fraud that many had feared.

“I’m suspicious, but I have to do something,” said Manar Ahmed, a 27-year-old trying to make a career transition from call center work to tourism. On Monday, she heeded the call of Egypt’s revolutionary youth parties, which urged people to vote and then join the anti-government sit-in at Tahrir now in its tenth day. She wore a colorful orange floral print headscarf and listened patiently as two of her friends explained why they were boycotting the election. Once they finished, she calmly but firmly disagreed.

“We’re going to make many mistakes along the way, but we have to learn from our mistakes,” Ahmed said. “We have to work, and see what happens. We still have to learn how to think.”

Revolutionary parties, consumed for the last ten days in a wave of murderous police violence and the protests it spurred in Cairo, Alexandria, and other cities, faced a quandary. Many of their supporters urged a full boycott. “If we vote, we give legitimacy to the military, which is illegally ruling our country,” said Albert Saber, 26, who refused to cast a ballot even though he had already chosen a line-up of independent pro-revolution candidates in his east Cairo district.

At the same time, the activist party leaders realize that the next parliament will play a key role in a transition to civilian rule, if one occurs, and they understand they might have more influence if they have a voice inside the chamber of deputies as well as on the streets outside.

“The next parliament will have no authority, same as the last one,” said Moaz Abdel Kareem, a youth leader and founder of the Egyptian Current Party, founded by liberal breakaway members of the Muslim Brotherhood youth wing. “This election is fake, a special effect to make it look like the military is working for the people.”

His party suspended its campaign, but its candidates still stumped in polling stations on Monday as part of their unified list, which they named “The Revolution Continues.”

There was a tangible sense in Cairo that street protest was being left behind, dwarfed by voter turnout and the cautious embrace of electoral politics that it heralded. With notably less enthusiasm than they showed during a national referendum in March — the first poll after the Tahrir Square uprising — Egyptians queued for hours, with a mix of muted excitement and markedly modest expectations.

“Change won’t come immediately. It will come step by step,” said Taghreed Ibrahim Hassan, 46. She had come to vote in Shoubra, Cairo’s most densely populated area, with female relatives spanning three generations; she stood out in the voting line for her loud laugh and booming exclamations of enthusiasm.

“This time our voices will count,” she said. “This parliament won’t represent us perfectly, but we won’t be stuck with it forever.”