Syria’s Stalingrad

Photo: JOSEPH EID/AFP/Getty Images

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

HOMS, Syria — More than four years of relentless shelling and shooting have ravaged beyond recognition this city, which once served as the symbolic capital of the revolution.

The buildings hang in tatters, concrete floors collapsed like sandcastles, twisted reinforced metal bars and window frames creaking in the wind like weather vanes. The only humans are occasional military guards, huddling in the foundations of stripped buildings. Deep trenches have been dug in thoroughfares to expose rebel tunnels. Everywhere the guts of buildings and homes face the street, their private contents slowly melting in the elements. Ten-foot weeds have erupted through the concrete.

As far as the government of Syria is concerned, the war in Homs is over. Rebel factions were defeated more than a year ago in the Old City, and the last holdouts, who carried on the revolt from the suburb of al-Waer, signed a cease-fire agreement this month. A few weeks before Christmas, busloads of fighters quit al-Waer for rebel-held villages to the north, under what the Syrian government and the United Nations hailed as abreakthrough cease-fire agreement to bring peace to one of the Syrian war’s most symbolic battlefields.

Gov. Talal al-Barazi, an energetic Assad-supporting Sunni, has been instrumental in pushing the cease-fires in Homs’s Old City and recently in al-Waer district. But almost none of the pro-uprising Sunnis who once filled its center have returned, and at times he seems to be presiding over a graveyard — an epic ruin destined to join Hiroshima, Dresden, and Stalingrad in the historical lexicon of siege and destruction.

By the end of a two-year siege of the Old City, the entire population of about 200,000 had fled, and more than 70 percent of the buildings in the area were destroyed. Today, according to the Syrian government, less than one-third of those who left have returned to the Homs area — but the ravaged city center is largely uninhabitable. Barazi said the cost of physically rebuilding the city would be enormous; without help from Russia, Iran, China, and other international donors, he said, full reconstruction would be impossible. Experts estimate it will cost upwards of $200 billion to rebuild across the entire country, or three times the country’s pre-war GDP.

And yet the Syrian government hopes to turn this shattered city into a symbol of its resurgent fortunes. Authorities showcase the reconstruction of Homs to spread a clear message: They intend to regain full control of the country. If they can tame Homs, a Sunni city where the majority of people actively embraced the revolt, they can do it anywhere.

There’s another more menacing message in the Homs settlement, however, as the neighborhoods that wholeheartedly sided with the revolution were entirely destroyed and have been left to collapse after the government’s victory. Almost no Sunnis have been allowed to return. Displaced supporters of the revolt from Homs understand that this is the regime’s second wave of punishment — they might never be allowed to go home.

This is the Homs model from the regime’s perspective: surround and besiege rebel-held areas until the price is so high that any surviving fighters surrender. The destruction left behind serves as a deterrent for others. Supporters of the government say that fear of a repeat of the ravaging of Homs is one major reason why militias around Damascus, like Zahran Alloush’s Army of Islam, have largely kept their indiscriminate shelling of the city center to a minimum.

The rebels, of course, take a different lesson: Assad will annihilate any opposition he can, unless the rebels fight hard and long enough to win, secure an enclave, or, at the very least, force the government to allow safe passage to another rebel-held area. Only force can extract concessions from the state.

A recent visit to Homs laid bare the deep divisions in the city and the near-impossibility of restoring what existed there before: a majority Sunni, but markedly mixed, community, more conservative and provincial than Damascus, but one that managed to successfully coexist despite profound communal differences.

As I stood in the middle of Khaldieh’s main square, in the center of Old Homs, I could recognize the bones of a familiar cityscape. Storefronts and five-story apartment blocks surrounded me. Avenues led in six directions from the roundabout.

I had seen this place before in video footage, when it played host to popular protests and later guerrilla fighting, and still later to a relentless barrage of Syrian government artillery intended to bludgeon all resistance. What remains today is an obliterated landscape that would be worthy of a dystopian sci-fi flick, if it weren’t so real.

The only sound, the ubiquitous sound, is the whistle of the wind, as loud as in the desert but incongruous in the heart of an ancient urban core.

My government minder fell silent after pointing out now-vanished landmarks. As we prepared to leave the square, she gestured dejectedly. “You can’t rebuild this,” she said.

The desolation continued for blocks in every direction, only abating up the hill toward Hamidiyeh, a mixed neighborhood to which a few dozen families, some Sunni, some Christian, have returned.

A bicycle parked outside a bombed schoolhouse is the only sign that you have reached the re-inhabited part of Khaldieh. Two boys kicked a soccer ball in a narrow courtyard delineated by rubble and broken walls. They pointed us in the direction of Maamoun Street, which begins at a grand Ottoman-era house, with a fountain and interior courtyard. One window had been refashioned into a sniper’s nest, a car frame shoved into the window.

Abdulatif Tawfik al-Attar, 64, is one of the few Sunnis to have returned to the Old City, the historic district near the center of Homs. Perhaps he was trusted by the government because of his outspoken criticism of the rebels, whom he said “came and destroyed everything.”

Now Attar is slowly rebuilding his shattered life. His wife and daughter live in a rented apartment on the outskirts of Homs while he restores their home to livable condition, room by room. Before the war, he worked as a mechanic at a government refinery. Now he repairs bicycles in his entryway.

He cherishes what he considers his ample blessings. All three of his children survived the war, he still draws a government salary, and the walls of his home are still standing. “For me, the situation could be far worse,” he said.

A chatty man who dropped out of high school for his first job, Attar finds it difficult to sit still. He’s ready to brew tea on a portable burner hooked to a car battery or prepare a water pipe for guests who like to smoke. But in the Old City, hardly anybody drops by to visit, except for a middle-aged neighbor also painstaking reconstructing his house.

“It is lonely here sometimes,” Attar admitted. He apologized for the spartan conditions in his home. His son invited the family to join him in Saudi Arabia, but Attar said he wasn’t interested. “I love my country,” he said. “I don’t want to live anywhere else.”

Quietly, he began to cry. “We have lost a lot in Syria, especially in Homs,” he said. “We didn’t used to have women begging outside the mosques.”

After a moment he said, “Homs will be back.”

The local Ministry of Information official charged with supervising journalists in Homs, an Alawite who also hails from the city, began to cry as well. One of her sons died fighting for the government in Daraa; her husband and remaining two sons are still on active duty in the military.

“We have lost so much,” she agreed, fingering the gold pendant she wears around her neck engraved with her slain son’s portrait. “Even our own children.”

Attar squeezed the official’s arm to comfort her. “Don’t be sad,” he said. “No one dies before it is written. People run away from the war to escape death, and they die in the sea. People went on the hajj, and 800 died in a stampede.”

One day the war in the rest of Syria will come to an end, they said, as it has in Homs — but if Syria is to recover, it will have to transcend the sectarian divisions exacerbated by the war.

“Those men who have hurt us have hurt themselves, too,” Attar said. “God knows what everyone has done. Human beings make mistakes.”

The minder quoted a saying she attributed to former President Hafez al-Assad, father of Syria’s current leader: “Religion is for God, and the nation is for everyone.”

“That’s how we grew up,” she said. “If you live in a country with government, land, home, you want to forgive so that you don’t lose everything.”

These pro-government Homs residents expressed nostalgia for a version of coexistence that worked for them. But the Assad government so far has offered rebels few options beyond submission and surrender — nothing that looks like increased rights for the majority of citizens. Homs Gov. Barazi, for instance, argues that as the city limps back to life, people will return, including Sunnis who might have sympathized with the uprising.

“Between Christmas and New Year’s, you will see a new Old Homs,” Barazi said, in an interview on the sidelines of a conference in Damascus about how to reboot the Syrian economy. “Once the shops open, you will see the things go back to life.”

He said the occasional car bomb or shell that strikes Homs didn’t threaten the city’s overall security. “It’s much safer in Homs than in Damascus,” he said.

Many government supporters don’t like the cease-fires that Barazi has championed, especially because they allow some fighters to flee and continue fighting elsewhere. The recent deal in al-Waer allows those rebels who surrender their heavy weapons to remain and govern their neighborhood. Activists suspect the government might round up rebels and dissidents later.

His strategy is to start with quick anchor projects in the worst-hit parts of Old Homs: rebuilding schools, historic places of worship like the Notre Dame de la Ceinture Church and the Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque, and now 400 stalls in the old marketplace. He is counting on Russia, China, and Iran to foot the bill of what will be an enormously expensive project. He estimates that maybe one-third of the displaced residents from Old Homs have returned to the city, if not yet to their original homes.

Several Christian parochial schools reopened this fall in the Hamidiyeh quarter of Old Homs. About 200 students came to the first day of school, out of a pre-war enrollment of 4,000 in the neighborhood, according to Father Antonios, a priest who helps run the Ghassanieh School. At pickup time, parents said they still didn’t feel safe in their old neighborhood. “We’re doing a lot of work to reassure people,” the priest said.

The government’s strategy overlooks the daunting, practical obstacles to resuscitating a city as thoroughly ravaged as Homs. It also ignores the bitter feelings of the people who supported the revolution and will never reconcile themselves to Assad’s rule.

Homs might yet be a model, but perhaps not the one intended by Syrian government officials — it might end up as this war’s lasting symbol of ethnic cleansing or urban siege war without restraint. The government’s showcase plan doesn’t make room for the legions of Homs natives who rose up demanding rights from a government that systematically tortures its citizens and allows them no say over how they’re governed. Anti-government activists also say that Sunnis are systematically denied permission to return to the Old City because authorities suspect that a reconstituted Homs will continue to act as a bastion of resistance.

“People still support the revolution,” said a retired resident, who never left Homs throughout the war. The resident spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of government retribution against his family members.

Homs proved the futility of expecting the Syrian government to reform, this resident said. He lamented how it responded to peaceful protests with lethal force and indiscriminate arrests and torture.

“For six months, no one carried so much as a knife. When the regime began killing them, they defended themselves,” the resident said. “I’m so sad about Syria. I stopped thinking about the future a long time ago. I live one day at a time.”

Periodically during the siege of al-Waer district, this resident smuggled in food and meat to civilians. With like-minded friends, the resident cheered advances of the rebel Free Syrian Army on battlefronts around the country. Today, the resident said, depression has set in, with the government precariously in charge of a city that once felt like the first liberated place in Syria.

“I feel like I will explode,” the resident said. “All these people died, in every possible way, for what? I can’t believe that everything will finish and Bashar al-Assad will still be president. I would rather die.”

Syria and the decay of the Arab state system

Old friend and colleague Eric Westervelt spoke with me on WBUR’s Here & Now about the diplomatic efforts to resolve the Syrian civil war, and the historical arc of the crisis in the Arab state system. You can listen here, or read the highlights as compiled by WBUR.

What are some takeaways from your time in Syria?

“There’s a bizarre sense of the clock having stopped somewhere in the 1960s or ‘70s when you step into regime-controlled Syria. The propaganda operation of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, the way it’s still trying to hold onto an absolute monopoly of dishonest manipulation and a denial of the barrel bombs and torture state. All these really crusty mechanisms of trying to maintain an old-fashioned authoritarian dictatorship seem really out of tune for 2015. We start with really small things, from just outright denial up until recently that the regime was losing the war, up to really big issues like that the secular authoritarian dictatorship hasn’t figured out a way to talk about how it wants to control a country that contains minorities but also religious Islamists, and we get to sort of this big historic arc of what’s happening in the region. The Arab state system that came into being at the end of the colonial period in World War II has proven unable to serve its citizens and it has set up a sort of horrible binary choice between secular dictatorships on one hand, and Islamist extremist groups like the Islamic State on the other hand. And neither of these poles represent the vast majority of citizens, and yet in the case like Syria’s, the regime and the Islamic State have wiped out almost every force that is moderate or even just less extreme and located between these two poles, so we have a region that’s still struggling to find avatars of the aspirations of the majority of its people.”

On the extreme “poles” Syrians are forced to decide between

“The regime and the Islamic State have wiped out almost every force that is moderate or even just less extreme… so we have a region that’s still struggling to find avatars of the aspirations of the majority of its people.”

“The Arab states like Bashar al-Assad, or Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt, or you could really pick your favorite offender, made a sort of dirty deal with the republics half a century ago. They said, we’re going to oppress you but we’re going to deliver modernity and progress, but ultimately they failed on their end of the deal. So people were oppressed and they also started getting poorer, less healthy, less educated and were missing out on what were supposed to be the benefits of this dictatorial trade-off. By design of these despots, the only viable opposition that was allowed to exist was extremist Islamist, and that self-fulfilling prophesy has led to a lot of the destruction in the region and yes, now we’re witnessing a tug of war between these extremes but the generational fight that we’re just at the beginning of is one where there’s going to be a third pole, which might not be liberal or democratic, but it certainly is not going to be something as extreme as the Islamic state. And that is, I wager, what is going to be dominating the region after this period of upheaval.”

On the views of ordinary people in Syria

“Well there’s two major groups that haven’t turned against the dictator. And one, are the real die-hard supporters of the old order, they’re not a small group. These are the ones who are, whether for ethnic reasons or because of their wealth and their well-being are tied to the regime support, aren’t going to abandon it. The other group, which is more interesting because they could shift, are folks like all the displaced Sunni Arabs and Palestinians I spoke to, who are turned off by the violence and extremism of the opposition groups, but they are in no way loyalists for the regime. What they like about regime-held Syria is that it’s a place that has room for many sects and many ethnicities and that welcomes people who are religious and people who are not religious. Beyond that, they are abused victims of the regime, like many people in the opposition areas and you can tell – some of them actually were able to speak openly about this to me – that they are yearning for some alternative, someone to be able to come and topple the regime but not replace it with a fascist religious order.”

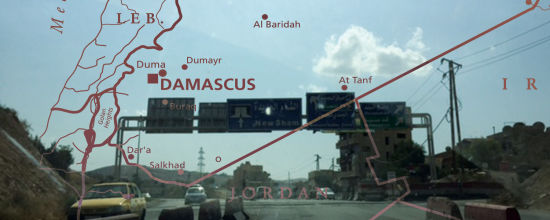

How close is the war for people in Damascus?

“The suburbs of Damascus, many are still in rebel hands. The period I was there in early October was relatively quiet, which means I would hear dozens of barrel bombs every night and more outgoing artillery than incoming, but there were several hits a night on the city and usually a dozen or so casualties ending up in Damascus hospitals. You realize when you drive around Damascus, you have to go around rebel-held areas to join the highway going north, that this really is a city surrounded by oppositionists and that it’s very tenuously held by the regime.”

Is there anything that gives you a glimpse of hope in Syria?

“The most positive thing about Syria is the one thing that’s always been positive, which is the tremendous human capital and talent of its people. Sadly today, a lot of the most promising Syrians have taken the refugee trail to Europe or are laboring away in exile as activists who are just trying to survive here in Lebanon, in Turkey, in refugee camps elsewhere. But there is an unbelievable amount of promise among this population and it’s a population that’s become very politically awakened and mobilized over the course of this uprising. So we have a reservoir of politically savvy, educated, polyglot skilled young people – young and middle-aged people – a lot of them with real technocratic experience. So in the very slim eventuality that Syria had a political transition, you’d be able to draw on a tremendous diaspora and population of recent emigrants just from the last five years who would have a better chance, maybe than any other Arab country, of building a functional creative successful new political order. So if I were looking for a ray of hope for the next five years or the next generation in Syria it would be that.”

Assad’s Achilles heel: The millions displaced inside Syria

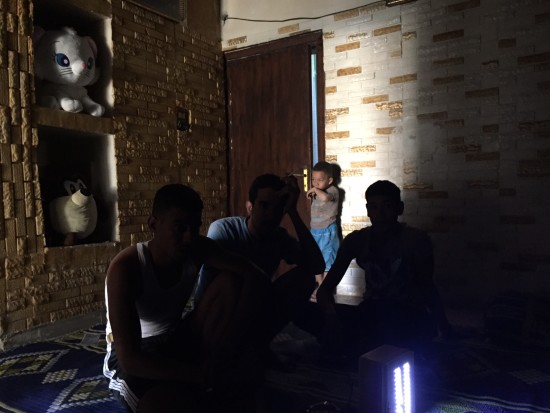

These displaced young Palestinians from a suburb of Damascus only were allowed to return home after signing a loyalty oath, but Syrian government soldiers still consider them a terrorist threat. Photo: Thanassis Cambanis

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

HUSSEINIYEH, Syria — The conquest of this Damascus suburb was supposed to be a success story for the Syrian government — a sign that after years of fighting, President Bashar al-Assad’s forces could defeat rebels and send displaced civilians back home. Instead, the halting repatriation of its residents stands as a daunting reminder of just how difficult it will be to reestablish order in a country shattered by war.

This small suburb southeast of the capital emerged relatively unscathed from a brief spasm of fighting between rebels and the Syrian military in 2013. By the end of that year it had been completely emptied of civilians. Once the government had driven rebels from the suburb and readied it for habitation, officials waited nearly two years before allowing a first wave of residents to return. A select group of a few hundred families were permitted back into Husseiniyeh this September, after pleading with the government and signing loyalty oaths. Following that first wave, over 4,500 families have returned, according to the United Nations.

Even within the tightly controlled, fortress-like perimeter of Husseiniyeh, army soldiers are jittery — their rifles at the ready as they warily eye the returnees, most of them government employees of Palestinian origin. Syrian authorities fear many internally displaced civilians support the anti-government uprising or are even secret agents themselves.

“Be careful,” whispered a nervous Syrian soldier as a group of teenage Husseiniyeh residents told me about their plans to repair the family home and restock the appliance store. “Some of these boys are jihadis.”

Whether or not they were, the soldier’s anxiety spoke to the fragility of the return process here. The first wave of returnees admitted in September included members of “trusted” categories: soldiers, civil servants, and government contractors.

“Anything could happen,” admitted Izdeehar Hussein, 48, owner of the appliance store and aunt of the teenagers. She was one of the advocates who helped negotiate the Husseiniyeh return agreement with the government’s Ministry of Reconciliation Affairs. “They let us in first and said, ‘You promised you would keep this peaceful.’ This way they can keep things in control.”

The struggle to reestablish control of this small suburb reflects one of the Syrian government’s greatest challenges: What should it do with a massive number of displaced Syrians who could potentially become a fifth column in government-controlled areas or might even take up arms against the government as soon as they’re home again?

Even as Europe and the United States debate whether Syrian refugees pose a threat, Assad faces a much more acute problem at home — one that is orders of magnitude worse. According to Syrian officials, in some government-controlled areas like the coastal provinces of Tartus and Latakia, half of the population today consists of people displaced from areas now under the control of anti-government militias. And for all the government’s happy talk about displaced people well cared for and living under the hand of a fully operational state, Syrian authorities have fewer resources than ever with which to control or monitor citizens whose loyalty they doubt.

The number of displaced people inside Syria beggars belief. Nearly 7 million people are displaced across the country, according to figures from the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Another 4 million have fled entirely. Damascus hosts 436,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) and its suburbs more than 1.2 million, according to U.N. figures. Syrian government officials said some provinces have twice as many IDPs as the U.N. estimates.

Solving the internal displacement problem is key to Assad’s strategy, which requires reasserting dominance over Sunni areas and populations that took part in the uprising. But some international officials and analysts of the Syrian war argue that Assad has purposefully made it easier for Syrians to leave the country in order to reduce his IDP problem. This summer, Syrians who had previously been unable to obtain passports found officials willing to issue them in a week. Border restrictions were lifted, making it possible for vast numbers of Syrians to seek refuge abroad.

“They’re happy if they have fewer mouths to feed,” one U.N. employee in Syria said.

This policy has, in turn, exacerbated the refugee crisis in neighboring countries and Europe. About half of the local staff in one U.N. agency in Syria fled to Europe this summer, crossing the Aegean Sea to Greece in boats, the employee said.

* * *

Far from the front line, the new demographics of displacement are straining the social peace of a region considered Assad’s heartland.

In the coastal city of Tartus, Syrians who have fled fighting in the country’s interior have inhabited virtually every available structure with a roof, from office towers to construction sites. A few steps down the hall from the Social Affairs Ministry’s provincial headquarters, a jerry-rigged iron gate blocking a stairwell leads to offices which have been repurposed as homes for families from Aleppo, their foam mattresses neatly leaned against the wall to make room for water buckets and butane burners. This is Displaced Persons Shelter No. 1, which was established in 2012 by optimistic officials who thought the war would end quickly.

Today, 600 people from Aleppo live in that first center. They are the lucky ones: Their kids are in school, the government staffs a free medical clinic on the ground floor, and most of the shelter residents — from the war’s early waves of displacement — have full-time jobs. The provincial government of Tartus has opened up 21 more official shelters, which house only a small portion of the 370,000 registered IDPs, according to Nizar Mahmoud, head of the government’s humanitarian response in Tartus.

Rents have skyrocketed, and tensions bubble up between the displaced newcomers, many of them Sunni Muslims, and the local population, which includes a large share of Alawites, Christians, and other minorities. The Mediterranean coast represents the government’s most secure area, and the loyalist villages scattered across the nearby mountains are often referred to as the Alawite heartland. But even before the war, the major coastal cities of Tartus and Latakia were predominantly Sunni, and that percentage has only grown with the wave of displaced people.

The government watches the displaced population carefully, on the lookout for sleeper cells and rebel infiltrators. The government tries to downplay sectarian rhetoric, but it seems to consider the massive influx of newcomers a potentially destabilizing fifth column.

Vigilant locals, one off-duty military officer in Latakia insisted, were supplementing the strained capacity of the state’s many intelligence agencies, or mukhabarat. “We have the situation under control,” he said.

“Today, everybody has become mukhabarat.”

Resentment percolates quietly among the displaced civilians, the majority of whom are forced to fend for themselves. Officially, the state still guarantees social services for all, but in practice, hundreds of thousands of displaced people have fallen through the cracks. Many of the displaced have already moved three or four times, as the conflict kept spreading deeper into formerly safe zones or when they ran out of rent money.

The strains are obvious: Cafés and promenades are overflowing with the unemployed, and despite the government’s claims, thousands of children aren’t in school, and families that can’t afford housing are sleeping in parks or makeshift quarters.

The problems are even more acute further north along the coast in Latakia, which houses many more displaced people and is closer to the front-line fighting. Since 2014, many refugees from northern Syria have reported that they were turned away when they tried to flee to the Syrian coast from embattled northern areas around Idlib and Aleppo. The government denies such reports, but it wasn’t able to show this reporter any shelters or camps that housed people displaced by the last year’s fighting; all the IDPs showcased by the government to multiple visiting reporters from different outlets moved there in 2013 or before.

The lone Syrian identified by government officials who arrived recently was a post office employee named Khaled Badawi, 53, who was displaced from his home village in Idlib in 2011. He stayed there for four years, until March 25, when a rebel coalition swept into the city. On that day, Badawi’s 16-year-old son died in a rebel mortar attack as the family was crossing a government checkpoint. His surviving two sons are in the military.

Now he collects a salary from the post office in Latakia, even though he admits there isn’t much for him to do there. Like dozens of displaced Syrians interviewed in their temporary homes, Badawi plans someday to return to his village, despite profound reservations.

He denied that the government has turned away IDPs from his area or that it gives special treatment to those whose family members are fighting for the government. He praised the government’s support but described a life of hardship. There was no place for his family in the city of Latakia, so they now live an hour’s ride away on public transport in a small village. “Everything is hard now,” he said.

The challenges of building a new life on the coast are daunting enough, but the task of restoring peace to Badawi’s hometown in Idlib will be even greater. In the Idlib countryside, Badawi said, all the combatants know each other: Relatives and former friends fight with anti-Assad militias, while his sons fight for the government. When it’s over, he doesn’t believe supporters of both sides can live in the same town again.

“The man who threatened to kill me was my neighbor,” Badawi said. “He will not be my neighbor again. It will be me or him. There is no trust at all anymore.”

* * *

Trust in the government has also eroded among some IDPs, though criticism remains muted for fear of being branded a terrorist or opposition fellow-traveler. In Damascus, a Sunni-majority city surrounded on several sides by anti-government rebels, the strain placed on the government’s limited resources is more visible.

Many of the displaced in the capital have come from rebel-held areas under steady government bombardment to suburbs like Jaramana, south of the city center and a few miles from front-line fighting. Some 1.6 million people in search of affordable and safe quarters have crowded into a neighborhood meant for one-third that many people. Beside a busy government checkpoint, two families were renting a windowless ground floor room that before the civil war was used as storage space.

Iman Araouri, 45, was recuperating from a stomach operation but was unable to afford the medicine and nutritional supplements prescribed by her surgeon. Her husband’s salary as a municipal janitor, about $85 per month, goes entirely to their rent. They cannot afford mattresses or blankets nor can the extended family’s children attend school.

To qualify for government services, including school enrollment and extra food rations, they need papers that prove where they lived originally. Araouri’s cousin, Marwa Bashir Hamoud, 31, said she crossed rebel lines, braving the same militiamen who murdered her husband in search of documents from her home. But when she reached it, she said, it had been looted. There was nothing left.

Hamoud tried to enroll her daughter in school after hearing a government announcement on the radio. “The minister said on the news that we can put our kids in school no matter what has happened to our papers,” Hamoud, who has four children, said she told the admissions official in Jaramana.

“Go and tell that to the minister,” the official told her, turning her away.

The IDPs are careful not to directly criticize the government, but at least some of their complaints are clear. Araouri said she has a brain-damaged 17-year-old son who lives in hiding at a relative’s farm; she’s afraid that despite his condition, he’ll be drafted into the army.

“Somebody has to take care of us,” Araouri said. “We are going back to Stone Age life.”

These personal tragedies echo in households across Syria, multiplied millions of times over. The Assad government fervently promotes the idea that the state still functions and that it earns the loyalty of the Syrian public. But the reality of wartime Syria differs greatly from the ideal propagated on state television and in the dispatches of the government’s rose-tinted Syrian Arab News Agency.

If the Palestinian suburb of Husseiniyeh is any indication, where it took nearly two years after the end of fighting for civilians to return, the Assad government’s piecemeal approach to restoring control will progress slowly. The displaced population will likely be an ongoing source of instability — a rolling earthquake that never fully stops.

“Here, by the grace of god, the war has ended,” said Khaled Abdullah Hussein, 64, a retired customs agent and a leader of the committee of local notables that negotiated Husseiniyeh’s reconciliation agreement with the government. With more than half of Syria’s territory out of the state’s control, and much of the rest threatened by rebels or jihadis, officials have their hands full, Hussein said. “The government doesn’t have time only for Husseiniyeh.”

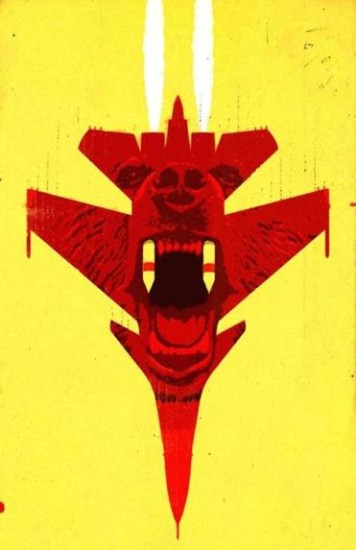

Putin’s crushing strategy in Syria

Illustration: RICHARD MIA FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

LATAKIA, SYRIA

WHEN RUSSIAN JETS started bombing Syrian insurgents, it was no surprise that fans of President Bashar Assad felt buoyed. What was surprising was the outsized, even over-the-top expectations placed on Russian help.

“They’re not like the Americans,” explained a Syrian government official responsible for escorting journalists around the coastal city of Latakia. “When they get involved, they do it all the way.”

Naturally, tired supporters of the Assad regime are susceptible to any optimistic thread they can cling to after five years of a war that the government was decisively losing when the Russians unveiled a major military intervention in October.

Russian fever isn’t entirely driven by hope and ignorance. Many of the Syrians cheering the Russian intervention know Moscow well.

A fluent Russian speaker, the bureaucrat in Latakia had spent nearly a decade in Moscow studying and working. Much of Syria’s military and Ba’ath Party elite trained in Moscow, steeped in Soviet-era military and political doctrine, along with an unapologetic culture of tough-talking secular nationalism (there’s also a shared affinity for vodka or other spirits).

The Russians have announced that they will partner with the French to fight the Islamic State in the wake of the terrorist attacks in Paris. But beyond new friendships forged in the wake of the Paris massacre and the downing of a Russian charter flight over the Sinai in October, Moscow’s strategic interest in Syria is longstanding and vital to its interest.

The world reaction to the Russian offensive in Syria has been as much about perception as military reality. Putin, according to Russian analysts who carefully study his policy, wants more than anything else to reassert Russia’s role as a high-stakes player in the international system.

Sure, they say, he wants to reduce the heat from his invasion of Ukraine, and he wants to keep a loyal client in place in Syria, but most of all, he wants Russia’s Great Power role back.

For all the mythmaking and propaganda, there is a powerful historical context to Russia’s latest foreign military intervention. Like all states that try to project force beyond their borders, Putin’s Russia faces limits. But those limits differ markedly from those that doomed America’s recent fiascoes in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The spectacular international attacks by Islamic State militants against targets in the Sinai, Beirut, and Paris have reminded Western powers of the other interests at stake beyond a resurgent Russia and a prickly Iran. Until now, Russia’s new role in Syria has stymied the West, impinging on its air campaign against ISIS and all but eliminating the possibility of an anti-Assad no-fly zone.

Russia’s blitzkrieg in Syria might have only tilted the conflict in Assad’s favor, with no prospect of securing an outright win for the dictator in Damascus — and yet, that might be more than enough to achieve Russia’s limited objectives.

As a result of a bold, arguably cynical, gamble, Putin might just get what he wants.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER WORLD WAR II, the Soviet Union quashed armed insurgencies in many of its newly annexed republics, including Western Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Western Belarus.

Those early campaigns shaped a distinct Soviet approach to counterinsurgency, according to Mark Kramer, program director of the Project on Cold War Studies at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

The United States was at the same time developing its own theories about winning over local populations, which underpinned the doctrine of “population-centric” counterinsurgency that ultimately failed to accomplish American aims in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s.

The Soviet Union, on the other hand, developed what Kramer calls “enemy-centric” counterinsurgency: Kill the enemy, establish control, and only then sort out questions about governance and legitimacy.

Harsh tactics worked for the Soviets. Kramer quotes the future Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev directing his agents in 1945 Ukraine to use unbridled violence against insurrectionists: “The people will know: For one of ours, we will take out a hundred of theirs! You must make your enemies fear you, and your friends respect you.”

In 1956, the Soviets used similar tactics to crush an uprising in Hungary. Despite the widespread perception of failure in Afghanistan, says Kramer, the Soviets had successfully propped up their local client, at great but sustainable cost, until Mikhail Gorbachev decided to repudiate the war there — just before US antiaircraft missiles arrived in the theater.

Vladimir Putin, insulated from political pressure, has drawn on this history to craft a brutal approach to counterinsurgency.

The first post-Soviet president, Boris Yeltsin, presided over the weakening of the Russian military and a desultory defeat at the hands of rebels in the first Chechen war of 1994 to 1996. As Putin prepared for a second Chechen war, in 1999, he used political coercion to guarantee friendly media coverage from Russian television and erase any meaningful political dissent over the war.

“During Putin’s [first] presidency, the Russian government was able to quell the insurgency in Chechnya without, in any way, having ‘won hearts and minds,’ ” Kramer wrote in a 2007 assessment after the Chechen war was provisionally settled in Putin’s favor. “Historically, governments have often been successful in using ruthless violence to crush large and determined insurgencies, at least if the rulers’ time horizons are focused on the short to medium term.”

Kramer compares Putin’s approach to that of Saddam Hussein, Stalin, and Hitler. It also seems very similar to Bashar Assad’s strategy today in Syria.

With no need to worry about public opinion, Putin’s counterinsurgency could kill countless Chechen civilians. When retaliatory Chechen terrorist attacks killed hundreds of Russian civilians in theaters and schools, Putin’s campaign only gained support. Russia’s flawed strategy in Chechnya ultimately created an outcome that worked for Putin.

“Historically, insurgencies tend to last eight to ten years, and most of the time Soviet and Russian forces have achieved their goals,” Kramer said.

Today Russia can’t entirely ignore international opinion, which has run strongly against its intervention in Ukraine. Doubling down in Syria, it turns out, has created the possibility of an exit strategy.

“Putin’s trying to change the topic from Ukraine, and maybe he’s been successful on that,” said Thomas de Waal, a scholar at Carnegie Europe who wrote a book about the Chechen war and closely follows Russian policy.

The style that Russia has honed — “overwhelming force as your basic strategy,” de Waal said — fits well with Assad’s merciless shelling of opposition areas. “You treat every enemy city as Berlin, and you pulverize it,” de Waal said, describing Putin’s approach to insurgencies. “There’s no subtlety, no regard for collateral damage or civilians.”

STATE MEDIA IN SYRIA has continued to herald the Russian intervention as a massive game-changer, but on-the-ground realities have already brought short initial expectations. Early predictions of a rout foundered when the Russians encountered resistance.

Anti-Assad forces, as any longtime observer of the conflict would have predicted, continue to fight back hard. Local militants defending their communities rarely quit; when they are defeated, victory can require months or years of fighting. In response to Russia’s escalation, the United States and other foreign backers of anti-Assad militias opened the spigot of aid including antitank missiles. Jihadists are equally formidable foes.

Assad appeared to be on the losing end of a stalemate before the Russian intervention. A major coordinated push by Russia, Iran, and the Syrian government could turn the momentum the other way, but analysts of the conflict doubt there’s any prospect of an outright victory.

Once the dust settles, the Syrian government will still suffer from the same manpower shortage that has plagued its efforts, and antigovernment forces will remain entrenched, said Noah Bonsey, Syria analyst for International Crisis Group. With Russian help, the government has gained ground around Aleppo but has lost some around Hama.

“In real military terms, it gets us right about to where we were before the intervention,” Bonsey said. “We haven’t seen any significant breakthroughs.”

Some of the closest followers of the Kremlin’s designs in Syria and the wider Middle East, like Russian analyst Nikolay Kozhanov, argue that Putin was never aiming for a military solution in Syria but only to better position Russia in the diplomatic great game.

Another Russian analyst, Nadia Arbatova, a political scientist at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations, said Russia wants to regain influence by convincing the United States and other Western powers to join Moscow in a counterterrorism alliance. She doesn’t think the Kremlin has carefully studied its own history in foreign interventions. The Syrian intervention, in her view, is less about Syria than it is about showing the West that Moscow can project global power again.

“For the first time after the collapse of the USSR, Russia is conducting a big military operation outside the post-Soviet space,” Arbatova said. “Hence Russia is not just a regional center but a world power.”

The most important lesson from Russia’s counterinsurgency history might be its Machiavellian reading of the politics involved. Moscow, when it succeeds, lays out clear aims and then methodically deploys force and political tools to reach them.

In Syria, Russia has sided with a rigid regime that has demonstrated a rigid unwillingness to entertain any compromise at all with an uprising that has engulfed most of the country. Its main partner is the Islamic Republic of Iran, whose political culture, regional interests, and long-term goals differ greatly from Moscow’s.

Putin might find his Syrian adventure meets even more obstacles than his increasingly bold interventions in Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine. Although each of Putin’s previous interventions carried an increasingly costly international price tag, all of them came in the former Soviet space, in an arena where no outside power can freely maneuver.

Syria is a different story altogether, a civil war saturated with foreign proxies. Russia is intervening on behalf of a minority regime that has already been fighting at maximum capacity. On the other side is a fractured rebellion, trapped between government forces and the Islamic State — which despite its considerable failings and only tepid backing from the United States has managed to keep Damascus on the defensive.

In government-controlled areas, Assad supporters have fully swallowed the enthusiastic propaganda about the intervention, peddled by Moscow and Damascus both.

“It won’t be long now, it’s going to finish soon,” said one volunteer fighter for the Syrian regime, a 38-year-old militiamen in the National Defense Forces with the word “love” tattooed on his forearm, sipping juice at a seaside café near his base. By next summer, he predicted, the war would be over, thanks to Moscow. “There will be strong forces of Russians, Iraqis, and Syrians fighting together. We will be strong. We are at end of the crisis.”

History suggests a more pessimistic forecast. Russia might get lucky, winning a diplomatic settlement at an instant when the Islamic State’s attacks have prompted a confluence of interests. More likely, however, Moscow will settle in for a decade of crushing counterinsurgency in Syria, against foes with considerable legitimacy, who represent a possible majority of Syrians and have the backing of some of the world’s richest and most powerful states. Russia has the resources and security to wait and see how the long game plays out, but it’s unlikely to end with either the blitzkrieg for which Assad’s fighters yearn or the hasty and favorable political settlement that Putin’s diplomats are pushing.

ISIS’ rotten roots

ISIS fighters march in Raqqa, Syria. AP File photo.

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

I broke the fast this summer one night during Ramadan in Gaziantep, Turkey, with a pair of activists who worked for “Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently.” At great danger, their organization documented the atrocities of the Islamic State in its de facto capital, the provincial Syrian city of Raqqa.

That day in June, the father of one of the group’s members had been murdered in Raqqa in retribution for the activists’ work. The clean-shaven younger one, named Ibrahim, spent most of the meal on his laptop, messaging contacts inside the part of Syria controlled by the Islamic State and uploading videos. Neither man ate. ISIS had announced a bounty on all their heads, but the citizen-journalists had no plans to give up.

“We are all worried,” Ibrahim said when he packed up his computer. “I will continue this work under any condition. We already have lost too much.”

Earlier this month, I learned that Ibrahim had been beheaded by ISIS — not like his friend’s unfortunate father in Raqqa, in the lawless badlands of the caliphate, but in his neighborhood in the city of Urfa in the supposed safe haven of southern Turkey.

Ibrahim’s murder jolted me — it was yet another instance in which ISIS had snuffed out another life and encroached on the area marked “safe” in my mind. Such encroachments have become all too commonplace, and this November ISIS has made a quantum leap beyond what some imagined were the group’s constraints.

In quick succession, the group claimed responsibility for downing a Russian airliner over the Sinai, a pair of suicide bombings in residential Beirut at rush hour, and then the paralyzing Paris attacks.

As with Ibrahim’s assassination at an Urfa apartment, ISIS wants to sow a sense of insecurity. It is part of the group’s message and ideology: There are no borders. You’re not safe anywhere.

While it’s natural to feel fear — more about that reaction in a minute — we can also remember our outrage and our own power. The temptation to strike back or lash out usually colors the first sorties after a cataclysmic terrorist attack. The response often feels dumb, brute, misguided: bombing in order to do something, joining a war on a fanatical adversary’s terms rather than reasoning out the most effective response.

We’re wiser today than we were in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks — or at least we ought to be — and we have a great deal more data at our disposal. If we can sit still long enough to process our emotions and cut through the layers of obfuscation put up by the myriad combatants in today’s Middle East wars, we can see at least one clarifying truth: Bad government by bad rulers has created the most enduring problems.

An entire rotten cast of Middle East governments has spawned a lost era through misrule and repression. Rotten rulers are the root cause not just of the Islamic State but of hundreds of thousands of other deaths. A partial list of villains includes theocracies like Saudi Arabia and Iran, and secular nationalist states like Egypt and Syria.

Some of the killers are backed by the West, others by the East. Interventions and miscalculations have driven the rise of Al Qaeda and the Islamic State. The hapless invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan by the United States and of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union are both on this list.

Not all the malefactors are equally responsible, but all have contributed to the regional order of miserable governance. Until it is replaced with new systems of rule — systems that are more transparent and representative, less dependent on torture, exclusion, and corruption — the Middle East will continue to host murderous conflicts whose strategic impact will ripple into the West despite the West’s best efforts to pretend those conflicts can remain local.

On one level, the bloody propagandists of the Islamic State can feel like master puppeteers. Until ISIS apparently blew up a planeload of vacationers returning to St. Petersburg, Russia was lackadaisically going after ISIS targets while concentrating its firepower on other, less gruesome, opponents of the Syrian government. The United States and the rest of the anti-ISIS coalition were making little more than a show of bombing ISIS targets while passively waiting for better partners to appear with boots on the ground. Everybody with a stake in the Middle East who could feasibly do something about ISIS has consistently preferred to make other struggles a priority. A partial list of actors whose rhetoric against ISIS has far outstripped any action includes the governments of Syria, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and the United States.

Now, however, with our sense of relative safety punctured, ISIS is on everyone’s lips.

But it’s a mistake to fall into a war to annihilate one enemy (as a former US admiral, among many others, has now called for the West to do) while sparing the far greater culprit.

Bashar Assad, using barrel bombs, chemical weapons, and old-fashioned artillery, has killed far more civilians than the Islamic State — hundreds of thousands more. Saudi Arabia and Qatar have invested billions of dollars over decades in promoting intolerant education and preaching around the Islamic world. Saudi Arabia serves as a model of intolerant, repressive, sectarian governance, one of the richest and most influential of many such models in the region.

There’s not enough space to detail to the errant examples set by the most powerful countries in the Middle East, from the anchors of the Arab world (including Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and Saudi Arabia) to the critical non-Arab states that flank it (Iran and Turkey). And of course, foreign powers deserve their share of blame for toppling some states and propping up others.

But it should be heartening to realize that something as simple, and fixable, as bad government is responsible for most of the deaths in the region and for the power vacuums and state failures in which pathological movements like ISIS thrive.

Ultimately, bad governance is a problem that can be solved. It’s daunting but also empowering, because we can do something about it.

Caliph Abu Bakr’s pornographically nihilistic shock troops have already destroyed life in much of Syria and Iraq. Now they have penetrated daily life far from their home base, and their bombastic threats against other cities suddenly carry weight. How much should we fear for Rome, for Washington, for other cities their sinister, buffoonish henchmen might mention in future videos?

A spiral of global attacks like those we’ve witnessed this November provoke the same rage of the powerless that many of us felt on 9/11: They’re everywhere, we can’t stop them, we must destroy them.

A short drive from where Ibrahim was beheaded in what he thought was his safe home beyond the war zone, on the frontlines of the conflict with the Islamic State, the casualties number in the thousands every month. Unlike in the West, jihadi fundamentalists have wiped entire communities out of existence and have managed to change the entire way of life in cities like Raqqa, Manbej, and Mosul.

This is a time of seeming mayhem, when events eclipse our ability to keep pace. Columns of men, women, and children stream across Europe, trudging through the mud from their destroyed homelands in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, and the rest of the periphery of the West’s foreign policy misadventures.

The horrifying images of displaced families and drowned babies look like some catastrophe from World War II. Such disasters are not supposed to occur in our modern world. Nor are failures like Syria, where no government has followed a constructive policy that could contain the chaotic spillover of the conflict, much less resolve it.

Fear is a natural first response when confronted with the stream of painful events such as we’ve witnessed this month and this year. So are despair and fatalism. They are understandable, but there is much we can do. We can overcome the temptation to surrender to impulsiveness or passivity. A starting point is to return to fundamentals. Unjust states that rule through routine murder, torture, and arbitrary detention, will only breed bad outcomes.

Washington is one among many international power centers that stakes its Middle East policy on utilitarian partnerships with unsavory regimes, placing a bet that stability requires deals with devils. These bets have gone bad for all the players, however, ensconcing an entire region of tyrants. The short-term stability has grown shorter and shorter, while the long-term misery and disorder have swallowed up most of the supposed benefits.

Rule of law and just government need to become the end-game for Middle East policy. It’s not only the right thing, it will better serve the interests of peace, stability, and saving lives than the current dirty partnerships and deals. Repression, corruption, and coercion rot the fabric of society and make for rotten alliances, policies, and governments.

Until we recognize that repressive governments are doing most of the killing and maintaining the perfect conditions for murderous strife and nihilistic extremism, our machinations against the Islamic State are likely to lead to nothing more than another dead end.

Thessaloniki Symposium

Last month I spoke at a very engaging one-day symposium organized by Dimitris Kerides and the Navarino Network in Thessaloniki. There were challenging presentations about the future of the European Union, the immigration wave, Russia, and the lessons we can began to learn now about the fall of the Iron Curtain and the transitions in Eastern Europe.

You can watch all the presentations here.

Lebanon Can Survive Bombings but Not Its Own Failing State

Published at The Century Foundation.

BEIRUT—On Thursday night, a team of suicide bombers struck at rush hour in the crowded southern suburbs of Beirut. The attack killed at least 40 people, and would have killed many more had it not been for the bravery of a man who tackled one of the bombers. According to some reports, a third bomber was blown up before he could detonate his weapon.

For a year and a half, the southern suburbs have been relatively safe after a crescendo of attacks in 2013. The last major suicide bombing in Beirut struck near the Iranian cultural center on February 19, 2014. Since then, a combination of factors abated the toll on civilians, although there was a steady trickle of smaller attacks and foiled bombings.

The formula that successfully calmed the situation in Lebanon was built on three pillars: (1) security cooperation between Hezbollah, the Lebanese Army, and the Internal Security Forces; (2) intelligence cooperation between the major state and non-state agencies (General Security, ISF, military intelligence, Hezbollah and others); and (3) a political commitment from bosses of all sects to discourage attacks on civilians, deter jihadis, and pressure targeted civilians to refrain from reprisals.

The fact remains, however, that Lebanon has become embedded in the Syrian war, and already was fully enmeshed in the regional struggle between interventionist powers including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Syria, Israel, and the United States.

Hezbollah’s decision to openly enter the Syrian civil war on the side of President Bashar al-Assad made it inevitable that the war in Syria would reverberate in Lebanon, in one manner or another. Meanwhile, the Sunni community of Lebanon—whose share of the population is shrinking—has suffered a leadership that is inept, corrupt, and fragmented.

These dynamics have created a dangerous impasse. As in 2008, Hezbollah is demanding a greater share of government decision-making power, which from a realpolitik perspective is a winning argument. The Shia proportion of the population has continued to grow, and Hezbollah is indisputably first among equals in Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing system. It will never be strong enough to dominate the entire country, but today its raw power is unequalled: its base is hyper-mobilized, its militia is stronger than the national army, and it has a symbiotic, possibly controlling relationship with the armed forces and General Security.

And as in 2008, there is standoff over filling the presidency, which has been vacant since May 2014.

Hezbollah’s rivals can convincingly argue that party’s demand for more say over the government is distasteful, perhaps even morally wrong. But Hezbollah holds the winning cards right now, and will likely get what it wants—probably after some avoidable and bloody showdown, like the battles in Beirut and the Chouf in May 2008, which convinced the anti-Hezbollah bloc then that it was too weak to press its demands.

Over the short term (which I’ll loosely define as the likely span of the Syrian war, which will probably last another five to ten years), Hezbollah will remain the preeminent power in a Lebanese system that functions like a mafia oligarchy, controlled by a small number of undemocratic, unrepresentative leaders whose primary interest is enriching themselves and perpetuating their power. This cult-of-personality/balance-of-power bonanza of corruption and misrule has proved highly elastic.

In its favor, the system prevents any single strong group, even Hezbollah, from dominating the others outright, and for twenty-five years it has served as a powerful buffer against a renewal of civil war. Its downside is that Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing deal has evolved in true mafia style into a free-for-all for the dons and their foot soldiers, with literally nothing left for the citizens of the country. A poorly run failing state in the 1990s, Lebanon has slipped into a worse and worse condition such that today, almost nothing functions.

There is no president, and parliament can’t even meet to authorize disbursement of funds—which would mostly be siphoned off in corruption and patronage schemes anyway. Garbage processing shut down over the summer, and today Beirut’s trash is spirited out of wealthy neighborhoods and dumped in rivers, alleys, and the poor quarters while politicians fail to agree on a way to handle the nation’s waste. Bribes and inefficiencies are ubiquitous, affecting everyone; just this week, in fact, corrupt customs officials held up a set of house keys my friend had express-mailed back to me until we paid a $15 “tax” charge. Some citizens find it impossible to obtain basic services from the state, such as the issuing of an ID card or the registration of a contract. Even those willing to pay bribes sometimes can’t even cut through the mess.

In this environment, many factors augur poorly for the long term.

The conflicts in the Levant and throughout the Arab world are fully regionalized, connected to a web of external actors, transnational movements, and activist governments. Syria and Lebanon are both organic parts of a regional conflict, prey to local dynamics as well the Iran-Saudi regional struggle.

Hezbollah’s short-term position remains secure, because its base supports it more strongly than ever. Over the long haul, however, it has lost any credibility as an umbrella actor with a unifying national project in addition to its own agenda. Hezbollah, despite its history galvanizing resistance to Israel, today has been reduced in the eyes of many of Lebanese and regional observers to another parochial sectarian group that works in lockstep with a foreign patron.

Sunni leadership has fragmented, leaving its constituency vulnerable and exposed. As a result, many Lebanese Sunnis operate without a sense of political cover, and in many areas like the impoverished northern district of Akkar, without even the minimal services that most other Lebanese can enjoy. This disarray has left a vacuum in which extremists such as ISIS can operate and recruit, and in which Lebanon’s many political crises could climax into a destabilizing game of chicken.

None of the status quo actors want a civil war, which is the most compelling reason why even if today’s breakdown is resolved by a militia showdown, the violence is likely to be contained. Lebanese factions who want to shoot it out have ample opportunity to do so across the border in Syria.

Sometime in the next year or two there will be another deal like the one negotiated in Doha in 2008. That accord postponed a reckoning and committed Lebanon to a nasty bargain: a sloppy simulacrum of peace in exchange for a continuation of the warlord oligarchy. Lebanon’s blueprint forward is crisis, breaking point, and another version of the same bad compromise that has survived in various guises since the 1943 national accord.

But the country that set the regional standard for a functional failing state is failing more than ever before. Brand Lebanon is broken, and the country’s major political parties own its misrule. That means Shia Hezbollah and its allies, and Saad Hariri’s Sunni Future Movement and its allies, are responsible not just for keeping a tense and violence-wrecked country from sinking into violent strife; they’re also responsible for the fact that nothing in the country works, for the failure of the government to deliver reliable electricity, water, or policing a quarter century after the end of the civil war, despite Lebanon’s obvious wealth and human talent.

In the long term, Lebanon will have to negotiate an entirely different system that creates a new level of accountability and representation for citizens. Failing that, Lebanon needs to find a way to function technically at the level of much poorer but better organized states in the Middle East North Africa region, such as Jordan and Egypt. Generations of corruption and mismanagement have driven Lebanon’s expectations to an abysmally low point, of which the limping state still falls short. Until that underlying failure to govern is resolved, Lebanon will simply cling on from crisis to crisis.

Assad’s Sunni footsoldiers

Ahmed al-Alaby comforts a neighbor who has lost a close relative in the conflict, outside the family home at a security checkpoint in Damascus’s Old City. Photo: Thanassis Cambanis.

[Published in Foreign Policy. I’ve collected additional photos and dialogue from the Al-Alaby family in this Atavist piece.]

DAMASCUS — The assassins struck the one place they knew Mohammed Ghassan al-Alaby would brave the death threats to visit: his beloved cousin’s grave.

Mohammed and his brothers rarely left the alleys of Damascus’s Old City after al-Nusra Front, an al Qaeda affiliate, claimed responsibility for the murder of their cousin Ihab in the summer of 2012 and swore to kill them, too. The men of the Alaby family stood accused of betraying their sect: They are Sunni Muslims who had refused to join the anti-government uprising and instead were serving as guardsmen in a pro-government neighborhood watch group.

Ever since Ihab had been gunned down in a drive-by shooting, the Alaby brothers had kept a low profile — except for weekly visits to his grave in Bab al-Saghir cemetery, just south of the Old City’s walls.

On the day of the attack, March 8, 2013, Mohammed and his two brothers had just bowed their heads and recited the opening verse of the Quran, when an explosion blasted from the head of the grave. Mohammed fell forward onto the grave just as another bomb went off. His brothers believe he died instantly, his body absorbing the force of the second blast and sparing them.

The Alaby family hails from the Syrian civil war’s least understood demographic: fence-sitting Sunnis who eschewed the uprising but aren’t entirely trusted by the government. They’re trapped between religious extremists and a government that often treats them as second-class citizens. The Alaby brothers consider themselves defenders not of Bashar al-Assad’s government but rather of a neighborhood and a Damascene way of life, a society that welcomes anyone — secular, atheist, or a member of any faith. But for members of the predominantly Sunni armed opposition, they are traitors — co-religionists who have taken up arms to defend the Alawite-dominated government.

“We’ve never disturbed anybody,” said Mohammed’s brother Assad, 40, who is now guardian of his brother’s children and chief of the guard unit that operates out of his home. “We are only protecting our area.”

But despite their dire straits, Sunnis like the Alaby family might hold the key to Syria’s future. Sunnis made up about three-quarters of the pre-war population, and the country’s economy still revolves around a wealthy Sunni merchant class. Sunni industrialists in Aleppo, the country’s manufacturing base, have kept factories operating despite a degrading battle over the divided city, while displaced Sunni entrepreneurs on the coast have opened new business, often creating jobs for other displaced Syrians. Some Sunni business owners have fled or thrown their support behind the rebellion, but many rich Sunni industrialists serve as pillars of the regime. If they mobilize en masse, they could tilt the outcome of the war, and in its aftermath their buy-in will be a necessary building block of any sustainable new government.

In Syria’s conscript military, Sunnis traditionally made up a large number of lower-ranking soldiers, in proportion to their share of the general population, according to analysts who study the Syrian armed forces. Even today, rebel videos showing captured government soldiers reciting their names and hometowns almost always include Sunni conscripts, for example. Aron Lund, editor of the Syria in Crisis blog at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said the government still relies on Sunnis to fill its fighting ranks.

“There are Sunni Muslim Syrians fighting on the front line for Assad even today, even though many may be conscripts or fight simply for a living wage,” Lund said. “The regime was really bleeding Sunni support in 2011 to 2013, but then it seemed to stabilize to some degree.”

The regime has always carefully cultivated support across sects, Lund said, filling the security services with loyalists of every religion and from major tribes. After a wave of defections in the early stages of the civil war, many Sunnis stayed on to play prominent roles, including the defense minister. However, the continued presence of high-ranking Sunnis in the military could be little more than window dressing. Historically, Lund said, “the over-representation of Alawites was tangible, and there was a tendency to favor Sunnis for publicly visible posts, like minister of defense or minister of interior, while the unseen deep security state remained mostly Alawite-run.”

Perhaps motivated by fear or simply for lack of a better alternative, many Sunnis remain on the government’s side. But for now, they’re often a hunted class of citizens. Many Sunnis like the Alaby brothers living in government-controlled Damascus describe living in a Catch-22: They risk their lives fighting to keep the extremists from al Qaeda and the Islamic State, also known as ISIS, out of their neighborhoods — but the government they’re defending considers them potential fifth columnists, their loyalty always subject to question.

“Here in the Old City, everybody knows me, and I’d say they trust me 70 percent. Outside, I’m just another Sunni,” said one secular Sunni, whose entire family refuses to leave the Old City for fear of arbitrary detention at a checkpoint. “We have no future under this regime, but if ISIS comes, it will be worse.”

The Alaby family went a step further than other Sunnis in their neighborhood, many of whom sat out the rebellion. When Damascus came under sustained assault in 2012 and anti-government militants infiltrated even the heart of the capital, the brothers purchased guns and organized a watch group.

Soon men began calling the family’s home with death threats. They called the Alaby brothers shabiha, a derogatory nickname for pro-regime militiamen. In June 2012, they killed Ihab. The following spring, nearly a year later, Mohammed’s mother received a call. “We have prepared a special Mother’s Day present for you,” a voice said. On March 8, 2013, just a week after the call, her son was killed.

In the two-and-a-half years since, Mohammed’s surviving family members have continued to patrol their neighborhood. Their neighborhood watch is now part of the National Defense Forces, a network of local militias that operate in the areas where they’re from and are in part trained and fundedby Iran. The Alaby family members don’t leave the Old City: They are committed to protecting their neighborhood, not to fighting the government’s war on other fronts. And they’re convinced that al-Nusra Front spies track their movements; that’s how they were tracked to the cemetery for the attack, they said, and that’s why they continue to receive threats.

“These people, you can’t discuss with them,” Ahmed al-Alaby said of his enemies. “They will kill us directly. Our names are everywhere. We don’t fear for our own lives, but we are afraid for our children.”

They’re careful to refer to the current president of Syria as “sweet,” but say they are motivated by parochial neighborhood interests rather than a presidential agenda. They work at their business all day and with the National Defense Forces at night. The family metalworking factory in the suburb of Mleha produced pots, pans, and other metal housewares; since fighting broke out around the capital, the brothers say it has been too dangerous to reach. Now the three surviving brothers work on a much smaller scale out of their home in the Old City, producing a line of kettles and pots.

On a typical weekend afternoon, Assad, the eldest surviving brother, played a video game on his phone and smoked in the dark in his home office while waiting for one of the daily electricity cuts to end. The entire extended family, 23 members strong, has crammed into a tiny apartment — unable since 2011, the first year of the war, to return to their homes in the contested suburbs of Damascus. One day, they hope they’ll move back to their spacious homes outside the city.

The main room holds a kitchen with floor space for the family to sleep. On the right is the local militia office: clipped high on the wall — and safely out of reach of the children — are seven AK-47s. There are also portraits of Ihab and Mohammed, as well as former President Hafez al-Assad, though not of his son. A sophisticated radio system sits on Assad’s desk. Tucked beside it are four water pipes to smoke the long night-watch hours away.

“Many have been wounded by this war, one way or another,” Ahmed said, tugging at his undershirt to show the shrapnel scars on his chest from the graveside attack. Comfort, he believes, will come only from God.

One of their sisters immigrated to France before the war. The brothers have debated about whether to join her, but they hate the idea of abandoning their home and becoming refugees in a distant land. “There is no future for our kids here,” Ahmed, 29, said gloomily. “The only reason we think of leaving is for them. Life is hard. We are so many. It’s very expensive.”

Mohammed’s 5-year-old son wandered into the office and climbed into his uncle’s lap. Assad pulled a comb from beside his walkie-talkie and rifle, and straightened the boy’s hair.

“Where’s your father?” he asked.

“He was killed,” his nephew answered softly, smiling.

“Who killed him?”

“The free army,” said the boy, conflating the nationalist rebel group called the Free Syrian Army with the Islamist jihadis in al-Nusra Front who claimed responsibility for killing his father.

“Where is he now?”

“Paradise.”

“Now go play,” said his uncle, letting the boy slide off his lap.

Mohammed is now buried with his cousin in the plot where he was killed at Bab al-Saghir cemetery. Within the sometimes claustrophobic confines of the Old City, coexistence continues, but the war has deepened sectarian identities. The Alaby brothers have to sneak into the cemetery for their occasional visits, telling no one where they’re going.

Their world grows narrower every day, with fear and uncertainty the only constants of their lives, said Assad, the weary paterfamilias.

“Every day we leave our homes,” Assad said, “we don’t know if we will die on the way or never come back.”

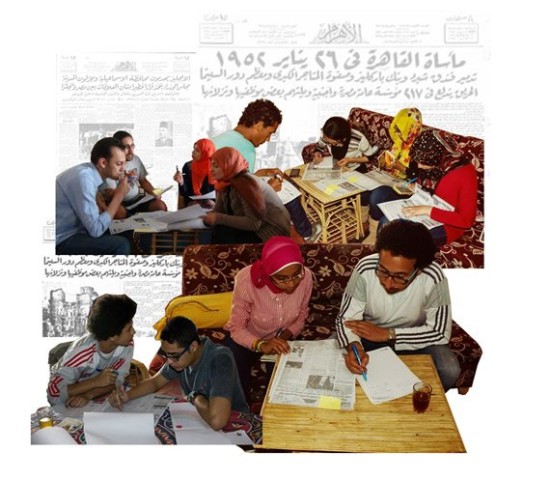

A nation exhausted: Portraits of Syria

After Eid I spent ten days in Syria, doing my best to collect as many individual impressions as I could. Everything about the trip was limited, but I was lucky enough to have many people share some part of their stories on what was ultimately a very fragmentary, kaleidoscopic, picaresque jag through government-controlled Syria on an itinerary and schedule largely not of my own design. And yet, the human stories seep through — even in these amateur snapshots I made with my phone. These images offer but a sliver of perspective. Yet still I believe they’re worth scanning through, to catch a glimpse of quotidian life.

Assad pays respects to Putin

Syria’s president paid a visit to Moscow this week, maybe to say thank you, maybe to pay fealty to a sponsor, maybe to hear some requests. Some compared the visit to the obligatory calls Lebanese presidents used to have to pay the Assads in Damascus. PRI’s The World talked to Neil McFarquhar about the visit, and then asked me about the lives of everyday Syrians I met on my visit to Syria earlier this month. You can listen here.

“There’s a sense of relief that the cavalry coming from Moscow is going to be much closer to the Syrian elite’s way of life than the Iranians who had been rescuing them until now,” Cambanis says.

For evidence of the comradery, consider the affectionate nickname Assad supporters have given Putin — “Abu Ali.”

“It’s a way of saying this guy is one of us, he’s going to be the godfather of our victory, and he’s a little bit of an old-fashioned strongman.” Cambanis says. “It’s sort of silly, propagandistic sycophancy. On the other hand, it reflects this thirst for an outside savior.”

Inside Syria: Q & A with TCF

I visited government-held Syria in October at a pivotal moment, gaining a rare glimpse into the part of the country still controlled by President Bashar al-Assad. The Century Foundation, where I am a fellow, asked about my impressions.

Q: What timing—the week you arrived, Russia unleashed its new military campaign. How did that change the outlook of the people you spoke with?

A: Russia came up in almost every conversation I had, whether with officials, fighters, or regular citizens. The war has dragged on for nearly five years, and whatever they claim, most people in Syria understand that it’s a stalemate that neither side is likely to win outright. For people living in government-controlled Syria, the Russian intervention has—for now—lifted the sense of fatalism. With Russia boldly on Bashar al-Assad’s side, the thinking goes, maybe the Syrian government can win outright. That’s created a palpable wave of optimism. Many people in the coastal cities of Tartus and Latakia told me they thought the war would now end within a year.

Q: Do you think it can end so quickly?

A: I doubt it. Russia’s move has completely shifted the geopolitics of foreign intervention and imposed new constraints on the United States and its allies. But most of the Syrians fighting against the government consider themselves patriots and are fighting on their own home ground. Contrary to Syrian government propaganda, which paints the rebels as foreign fighters and mercenaries, most of them are actually locals who prefer to die rather than surrender. Even if the government can defeat them with the massive push it has received from Russia and Iran, it will take a long time—probably two to five years—before they can reconquer the main rebel strongholds. And the buoyancy among government supporters (or even those who just want the conflict to come to any sort of end) will fade when they see that the rebels fight back, and that foreign interventionists on the rebel side can keep the fight going for a long time just by maintaining supplies of money, ammunition, and weapons.

Q: You had not visited Syria since 2007. What were the biggest differences that you noticed?

Government-controlled Syria feels beleaguered and utterly militarized. Assad’s Syria was always a heavy-handed police state, with intelligence agents everywhere and a huge web of agencies that detained people, tortured them, and kept them in fear. Today, the government has lost a great deal of its resources, holding maybe one-third of the country’s territory and controlling half or less of its remaining population. Yet, it retains its old heavy-handed style, and the displaced people living in the government areas are terrified of saying anything that might be construed as subversive.

Damascus is a beautiful city, and it was clean and well-run in 2007. For all the shortages today, it’s still functioning, but there are constant power cuts and real shortages of personnel and certain imported goods. There are checkpoints everywhere, and most of the men under 40 are either in uniform or are off-duty fighters.

Q: What was most on people’s minds?