US NATIONAL ARCHIVES

The gas crisis of the 1970s left many motorists stranded.

A terraced garden outside Mansion in Beirut. Photo: Diego Ibarra Sanchez for The Boston Globe.

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

BEIRUT — As a symbol of a lost era in a region full of them, Beirut stands apart. For generations it thrived as a center of culture, commerce, and education, until the 16-year Lebanese civil war fragmented the city’s diverse population and shelled its vitality into rubble.

The war ended in 1991, and today Beirut is mostly peaceful. Some of its glamour and wealth have started to return. Dazzlingly dressed Lebanese fill gallery openings; boutique wineries do a brisk business. Glass towers have sprung up around the new marina.

But in many ways, Beirut is still a failed city. Hobbled by ubiquitous corruption, rampant criminality, and the legacy of sectarian militias, Beirut still doesn’t have any of the basic amenities of urban life, like traffic police, a planning board, even a functioning sewer, water, or electrical system. It is no longer a business capital; the money on display here was mostly made somewhere else. The war-shattered UNESCO building squats in the heart of the city like a crash-landed spaceship. To the west, two shell-pocked skyscrapers mark the horizon, both them uninhabited since the civil war broke out in 1975.

Most obviously, Beirut needs to attract investment and solve its infrastructure problems. But to truly revitalize the region, it will need to do more than that: It will need to recapture the cultural energy that long marked Beirut as the intellectual capital of the Arab world. A small city that welcomed big thinkers, it was historically home to writers, philosophers, political dissidents, artists, and other creative types from around the region. That, more than any of the trappings of wealth and celebrity, made it a beacon.

This is where Ghassan Maasri comes in, or hopes to. Maasri is an architect who grew up amid the rubble piles, collapsing old houses, and construction sites of post-shelling Beirut. Today, he is two years into an experiment called “Mansion.”

Picturesque old family villas still dot the city, often in disrepair. More and more are being torn down to make way for profitable condos and office towers. Maasri convinced the owner of one to to let him create a nonprofit experimental collective there. His idea was to use it to foster a community of “Beirut city users,” ambitious professionals as well as creative artists, who would use the space to launch projects that make the city a better place to live.

“I want to be able to meet artists on the street,” Maasri says. “The process of producing art is very important for the modern city. Filmmakers, theater, fine artists, architects, designers—these are the things that make a city livable or interesting.”

Maasri’s Mansion collective has emerged as a nucleus for engaged Beirutis, and a fixture on the city’s cultural circuit. It’s too early to measure whether the initiative will help revive Beirut as an intellectual and cultural center, but Mansion is now part of a small ecosystem of institutions trying to redirect the way the city works. Nearby is another collective that’s trying to serve as incubator for Lebanese startups; other cultural organizations are trying to promote mainstream audiences for local filmmakers and artists. On the preservation front, a well-known painter has launched a campaign to save Rose House, an iconic mansion overlooking the sea from West Beirut’s bluffs.

Elsewhere in the world today it’s taken for granted that cities are engines for culture and growth, a place for creativity, money, and smarts to meet. Authoritarian rule has greatly diminished those expectations in the Middle East. If Mansion works, it will be a step toward restoring that spirit to a region where it’s been gutted by war and political stasis.

“I’m trying to find a way so that people can produce things inside the city,” Maasri says. “It’s an experiment. Let’s see how it goes.”

Ghassan Maasari, an architect who grew up among the rubble of the city, convinced the home’s owner to to let him create a nonprofit experimental collective. Photo: Diego Ibarra Sanchez for The Boston Globe.

IN ITS PRIME, Beirut was the kind of rich, important, stimulating place that today would be called a global city. The city supported daily newspapers in Arabic, French, and English. The most ambitious students in the region filled its universities. Its bankers were high-powered and urbane.

It was a city of beautiful alleys and an open waterfront, with an intimacy beloved by its admirers. The Rolling Stones liked to hang out here; an entire book was written about the writers, spies, and artists who orbited around one bar, in the St. George Hotel.

Money, not culture, has driven Beirut’s rebound since the end of the civil war. Political infighting has frozen the effort to fix the St. George, whose ruins blight the edge of the new marina, a soulless anyplace that’s hard to distinguish from Santa Monica. The old downtown, rebuilt by a politically connected developer, is an unused pedestrian area guarded by an army of private security officers. Martyr’s Square, the historic center, remains a sprawling unpaved parking lot because of a property standoff. The one major park that survived the war has been closed to the public ever since.

Warlords reached a compromise to end the war: Communities would coexist peacefully amid a low-grade simmering anarchy. As long as there was no national authority, no group could use it to dominate the others. As a result, Beirut is a city with few rules and no enforcement of building codes.

Maasri’s insight was to realize the anarchy might also have created a space to try something new. Now 42, he moved to Beirut as a child in the thick of the civil war; his family was fleeing the fighting in the nearby mountains. As the city came back to life in the 1990s, Maasri was horrified by the sheer waste. Artists were fleeing the city in search of affordable studio space, while thousands of buildings in prime locations sat empty and decaying.

Maasri first tried turning rental properties into communal studios, at cost, but found it too expensive. He won grant money to establish short-term artist-in-residence projects in abandoned properties in his hometown of Aley. With an eye to doing the same in Beirut, he wandered the city on foot, scoping out dozens of dilapidated Ottoman mansions that he thought would make an ideal space for a cultural collective. Every time he tried to contact an owner, he said, “I could never get past the lawyer.”

Finally in 2012 he got lucky. The owner of a grand three-story villa on Abdulkader Street was willing to meet Maasri directly, without any intermediaries. He had kept up his family’s 80-year-old Ottoman-style villa better than most; it was decrepit, but still had its doors, windows, and roof, which meant that unlike most of the similar homes around the city, it was inhabitable—if not comfortable. He was willing to loan it to Maasri for five years, free of charge.

The house couldn’t have been more centrally located: It was a few hundred yards from the Serail, the Ottoman barracks that now serve as the headquarters of the Lebanese government. Typically for modern Beirut, it is surrounded by four brand-new condo towers, an illegal squat, and a parking lot.

Maasri invited architects, artists, and people whom he loosely defined as urbanists to come populate it and fix it up. They cleared the vines and brush that had overrun the yard and were spilling into the street. They strung bare light bulbs from the ceiling, and turned the grand ground-floor entry hall into communal space that could host lectures, panel discussions, film screenings, and musical performances.

On a recent Saturday, a children’s event called “Mini Mansion” screened Charlie Chaplin movies. A party that evening promoted recycled glass. Earlier that week, Mansion had hosted a series of discussions about urban renewal, with panelists from Europe and the Middle East. There’s a design and architecture studio on the top floor, a silk-screen workshop, and a film archive. Upstairs, artists work on paintings and sculptures in their studios. A bike messaging startup called Deghri (Direct in Arabic) has its headquarters at Mansion, and is trying to establish bike repair clinics and a recycle-a-bike program for Beirut.

Residents pay a nominal rent to help cover water, electricity, food, and repairs. Most importantly, they are required to use their space, and ideally intended to bring even more people in. An urban gardening initiative was supposed to start a pilot program on Mansion’s roof, but never followed through; Maasri gave their spot to someone else.

Maasri himself lives in the crumbling but still grand three-story mansion. To make sure he isn’t breaking any occupancy rules, he has been officially designated the building’s doorman.

MANSION’S FOUNDER wants its spirit to spill beyond its walls. In January, Maasri is launching an “Inquisitive Citizens Urban Club” which will convene anyone interested in Beirut for a three-month study of public space in the city, with the ultimate goal of catalyzing urban activism. Other cities in Europe and United States have plenty of civic-minded urbanist groups. Here, however, it is groundbreaking.

The common theme running through Mansion’s projects is a hunger to reclaim public space. That’s a politically charged project in a city where big money drives the major development projects, and where the lack of public space is inextricably connected to the erosion of political and civic rights for citizens.

Beirut is the forefront of many interlocking debates about cities and the way people live in them. And that debate is critical right now in the Arab world. Increasingly, it has become a region of cities, as the population abandons the countryside in search of work and education. Yet the role of those cities is in flux.

Traditionally, Arab cities were cosmopolitan commercial and trading hubs, open zones with mixed populations. Today, the most dynamic examples of urban vitality in the region are the tightly controlled metropolises of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, wealthy cities with limited freedom and an economic model based on oil wealth, finance, and omnipotent royal families. A revitalized Beirut, with an openness to art, public initiatives, and intellectual culture, could be an alternative.

“If I have an idea, I don’t need money or approval to experiment,” says Ayssar Arida, an architect and urban designer who grew up in Lebanon and returned to Beirut two years ago after more than a decade in London and Paris. He was attracted to the freedom from authority. “Beirut is fantastic thinking matter,” he says. “It’s not totally gone to the dogs yet.”

His wife, French-Iraqi curator Sabine de Maussion, works out of a studio at Mansion, where the couple collaborated on their latest invention: a high-end construction toy called Urbacraft. Mansion is littered with conceptual models made from Urbacraft blocks (imagine an Erector set crossed with Lego, for design nerds).

Mansion can sound a little like a party for cool, arty elites. But that is not Maasri’s goal; he is wary of drawing shallow, trendy support. He wants people who are committed and willing to work to save a building, as a way of learning how to save the city around it. For now, Mansion is thriving, and it is his hope to leave the building and its neighborhood better off than he found them. Although he is hopeful that the owner will be impressed enough to extend the experiment, he won’t mind if three years from now he has to find a new home for Mansion.

To Maasri and his colleagues, it’s not buildings that make a city, but people who create things. They’re sad that so much of Beirut’s architectural heritage has been torn down in the rush to rebuild, but they have set their sights on something harder to define than preservation. If they can figure out how to keep creating in Beirut without depending on grant money or wealthy patrons, he believes they can bring back the best thing about Beirut—even if the glory days of its architecture have passed.

Egyptian youths shout slogans against the country’s ruling military council during a demonstration in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt, Nov. 30, 2011 (AP photo by Bela Szandelszky).

Egyptian youths shout slogans against the country’s ruling military council during a demonstration in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt, Nov. 30, 2011 (AP photo by Bela Szandelszky).Young people and youthful energy propelled the Arab uprisings that began in 2010. And while the cohesion and impact of vaguely defined “youth” movements have been overstated, they remain the most important potential source of change—the Arab world’s best hope. The small vanguard that drove the original uprisings is growing more organized and more ideologically sophisticated even as, for the time being, it has lost political ground.

Egypt has always set regional trends in political thought. Its Tahrir Square uprising raised expectations for democratic transitions throughout the region, although the other Arab revolts brought wildly divergent results, especially for youth. Today the military appears to have won in Egypt, but the long-term outcome of the struggle there between revolutionary and reactionary forces is still in question; how it unfolds will be a bellwether for the Arab world.

Youth Is a State of Mind

Basem Kamel makes an unlikely revolutionary youth activist. I first met him four years ago, inside the small tent erected by the Revolutionary Youth Coalition to house its big-tent deliberations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. He seemed decidedly middle-aged and established: balding, evenly shaved despite his sleep-deprived gaze, slightly stooped, his scruffy protest clothes accented with a knotted orange scarf. He was 41, father to three children, proprietor of an architecture firm. “Youth is a state of mind,” he laughed when I arched my eyebrows at his age.

But like the Revolutionary Youth Coalition and the fractious panoply of movements for which it briefly served as the umbrella, Kamel represented a radical challenge to the status quo. Against the mores of the ruling party, Kamel appeared young, pluralistic, open-minded, radically experimental and egalitarian. So were the other “revolutionary youth” I encountered in Tahrir Square, ranging in age from children to grandparents.

Kamel had gone within a year from apolitical observer to revolutionary policy wonk. He wanted to throw out the entire regime’s way of doing business along with then-President Hosni Mubarak. He wanted a rules-based social welfare state that encouraged entrepreneurship and initiative while efficiently taking care of the poor and vulnerable. He wanted justice for Egyptian citizens who had been abused by police and military personnel, and he wanted to see his fellow citizens learn to take responsibility for everything from litter to voting. “If we succeed, everything will have to change,” he said then. “It will take a long time.”

The Revolutionary Youth Coalition is no more. It collapsed a year and a half after its founding, because its secular and Islamist members lost trust in each other. It was the sole institution in Egypt that tried systematically to bridge the gap between Islamist and secular political actors. Elsewhere in the Arab world, only Tunisia’s Parliament has attempted the same feat, with equivocal success.

Yet despite its noble aims, the coalition also embodied the region’s political identity crisis in its very name. “Youth” and “revolution” are virtually meaningless as explanatory categories for what is taking place in Egypt and elsewhere across the Middle East. The Arab world today is in the grip of a regional struggle for control—and in some cases a fundamental redesign of government—being waged among many contesting visions: hereditary monarchs, old-fashioned nationalist states, incremental Islamists, nihilist jihadists, socialist reformers, anarchists and others. The young can be found in almost every one of these locales and movements, including the most reactionary establishment political parties and statist institutions. Similarly, some of the most creative and constructive political forces feature middle-aged or even old activists in inspiring roles.

The particular problems facing youth as demographically defined—completing secondary or higher education, finding a first job or career and establishing a family—are economic and social. And while young people have a special kind of energy that dissipates with age, none of these factors predispose the young toward any particular political tendency. Throughout the Arab region, as throughout the rest of the world, they are just as likely to be apathetic as political, or reformist as conservative.

Nevertheless, a set of new political ideas and processes has been unleashed in the Arab revolts. The energy of young street protesters catalyzed a moment of revolutionary potential, a moment that shattered the assumption of regime staying power and opened the way for competitive politics and new ideologies. That fundamental idea—that a peaceful popular movement can replace a repressive state with a responsive, democratic, just and egalitarian polity—has survived today in a battered condition.

In Egypt, the country with the greatest potential and the greatest political impact on other Arab countries, the idea of change survives mainly in the beleaguered family of “revolutionary youth” movements, for which the country’s broken political system has made no room. The story is different elsewhere. Tunisia, for instance, has a plethora of young activists but no predominant set of youth movements, most likely because the existing political structure, with its parties and trade unions, engaged in meaningful negotiation that was able to harness the energy of young revolutionaries and channel it into a successful transition to democracy. Lebanon offers a third alternative—a paralyzed dysfunctional state where established sectarian parties have managed to absorb and dissipate youthful energy and momentum for reform, without making any improvements in governance or way of life.

A close and honest look at the condition of the Arab youth movements tells us a great deal about the prospect for systemic change in the region. At the core of the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia was a group of movements that espoused an agenda much more about revolution than about youth. Its supporters were concerned with political and economic injustice, and they touted democracy in a local vernacular, refusing the notion that it is a tainted or premature import from the west.

The revolutionary youth have been roundly defeated in Egypt. Tunisia’s more successful uprising has subsumed most of its youth activists into mainstream parties, perhaps a sign that political life is healthy or diverse enough not to require a binary external category such as youth to advocate for reform. Elsewhere, youth movements have remained marginal, as in Lebanon, or been sidelined by violence, as in Syria, Libya and Yemen.

But there is a clear and admirable agenda, one quite threatening to the region’s status quo regimes, articulated under the banner of revolutionary youth. Any Arab state that doesn’t grapple with its central claims and aspirations will remain fundamentally insecure, under threat any time circumstances conspire to make an opening for the latent uprising incubating in the warmth of their misrule.

The Bulge

The Arab world is disproportionately young; more than half of the population is under 25. Education systems are failing. Young people make up almost all the new entrants to the labor market, and the Arab region leads the world in youth unemploymentaccording to the United Nations. Demographers and economists who look at the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have rightly called attention to the youth bulge, including a looming one in Egypt, coupled with the region-wide systemic failures to educate citizens and provide them jobs.

The considerable scholarship about the demographic and economic implications of the youth bulge explains one of the many dispiriting constraints on growth and quality of life in the MENA region. A recent United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) paper summarizes the reams of demographic and economic analysis of the Arab youth imbroglio: “Without noticeable improvements in their economies or employment prospects, especially for much of the frustrated youth, rising demonstrations, unrest and violence appear unavoidable for the nearly half a billion people in the Arab world by 2025.”

But “demographic destiny” and the depressing economic conundrums of the Arab economies tell us nothing about the likelihood of political explosions, transitions or repression. Poor states that have little concern with the rights and welfare of their citizens can still perform at dramatically different points along a spectrum from murderous and self-destructive, like Syria; to aggressively indifferent, like Egypt; to muddling but occasionally passable, like Jordan. Regimes with massive youth bulges can successfully crush dissent, as Iran did to the uprising known as the “Green Revolution” in 2009, or escape it altogether with minor adjustments, as Saudi Arabia has done since the Arab uprisings. Demographics are not destiny, politically speaking.

Egypt’s Movement Youth

The past two years have brought a crescendo of terrible news for supporters of pluralism, rights and democracy in Egypt. The country’s first and only elected civilian president, Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, ruled erratically and eroded civil freedoms. He was deposed in a popularly acclaimed coup in July 2013.

Reflecting the general patterns of society, an apparent majority of young people, including many activists, supported the anti-Morsi Tammarod protests. Only a tiny number of them immediately criticized the military’s direct takeover of power, although dissent quickened after the military regime massacred at least 1,150 Morsi supporters in Cairo’s Rabaa Square on Aug. 14. Egypt’s new leader, Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, swiftly moved to outlaw protest and ban the Muslim Brotherhood, and over time has arrested almost all the leading dissidents across the political spectrum. He has restored and intensified the repressive methods of the old regime and has banned critical figures from appearing in the media.

In one sense, the playing field looks like it did under Mubarak: A state behemoth that is terrible at governance uses a heavy hand to crush opposition, and faces a very small but committed activist community that includes old veterans and youthful newcomers.

But Sissi, a general who resigned from the military when he decided to seek the presidency almost a year after his coup, may face open revolt much earlier in his tenure than Mubarak, unless he indefinitely maintains his unprecedented levels of violent suppression. The generation of activists that propelled Tahrir has gone on to establish political parties, youth movements and other institutions. Its ranks have gained invaluable organizational experience. They have built vast interpersonal networks, bound by the shared experience of torture, detention, long prison sentences, exile and mourning. The brightest of the revolutionary leaders and movements have slowly begun to address their biggest failings; they are creating clearer, more compelling alternative ideas of governance, and they are developing strategies that take into account the volatility of mass public opinion.

Moreover, a significant portion of the socially conservative elite—the centrists who leaned slightly toward the revolution in 2011 and toward Sissi in 2013—has experienced political mobilization and the sense of power that comes with overthrowing a regime. Egyptians have acquired a taste for political empowerment and accountability.

A survey of the current state of the activist youth movements, as well as the widespread apathy among the youth demographic, can invite depression. Yet it is remarkable, especially when compared with the period before 2011, that in the face of historically unprecedented violent repression of all dissenters, from human rights lawyers to Muslim Brothers to bourgeois middle-aged civil society activists, a wide array of movements has persisted in opposition to the state.

Public opinion has gone into a version of political hibernation. Protests against Sissi’s government are small, and polls suggest transition fatigue. Some individuals who casually participated in protests or politics from 2011-2013 told me they had “lost faith in politicians,” “no longer trusted activists,” or were “ready for stability so I can get a job and have my life back.”

However, among the most dedicated activists, only a few have defected from politics entirely, while many have made notable shifts. Top among them are the organized revolutionary youth who have shifted allegiance entirely, best represented by the anti-Morsi Tammarod movement. Its original founders were five youth activists, including veterans from the April 6 Youth Movement and from former presidential candidate Ayman Nour’s Ghad (Tomorrow) Party. They mobilized a signature campaign against Morsi, and after the coup they became stalwart cheerleaders for Sissi’s elevation from junta leader to elected president. Tammarod is undeniably a reactionary force that has benefited at times from state support, but it is also undeniably a youth movement toward which Sissi’s government has turned a jaded eye.

Basem Kamel, the 41-year-old revolutionary “youth” I met in Tahrir four years ago, went on to co-found the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, which has now positioned itself to the right of its revolutionary roots as a traditional liberal party. He became one of just a handful of revolutionaries elected to the short-lived parliament of 2012. After the Sissi coup, Kamel and his party supported Sissi’s transitional government, prioritizing secularism and a fight against the Muslim Brotherhood over opposition to military rule. “I didn’t support Sissi, I opposed Morsi,” he told me this winter. “Whatever we are now, it is better than the Muslim Brotherhood.” He now sounds like a cautious reformer rather than a principled revolutionary.

Kamel opposes Sissi’s crackdown on protest and free speech, but he believes it will take years or decades for vanguard activists to convince the Egyptian public to support a genuine move away from military rule. He has chosen to work within a political party that has been allowed to continue operating by the regime as part of a trusted or permitted opposition.

Youth and revolutionary politics continue to exist, despite the crackdown under Sissi, because of systemic state failures. Police still torture with impunity; runaway judges make a mockery of the rule of law; army officers control political life; and the economy continues to fail the vast majority of its citizens, while a corrupt elite connected to the army and a ruling clique rakes in rentier profits.

And the most visible independent activists have continued to agitate, demonstrate or write treatises even from prison. Alaa Abdel Fattah, an independent leftist who helped form a revolutionary coalition after the Rabaa massacre, has produced a powerful oeuvre from his jail cell. Most recently, this fall he spurred a wave of partial hunger strikes under the slogan “We’re fed up.”

Meanwhile, the April 6 Youth Movement, a grassroots movement that has made deep inroads among working-class Egyptians, has survived a concerted effort by the state to dismantle it, in part because the movement’s leaders and members have in fact collaborated with right-leaning nationalists. These positions drew enmity to the movement, but they also put it more closely in step with the Egyptian mainstream. Perhaps for this reason, April 6’s grassroots network has survived the imprisonment of its leadership. As recently as November, it was able to muster a sizable protest in Tahrir Square, along with other secular, non-Islamist revolutionary groups angered by a judicial verdict clearing Mubarak of further charges.

Egypt’s Islamist Revolutionaries

The final locus of continuing resistance activity in Egypt comes from the Islamist space. Always the largest, most organized and best-funded opposition to the state, Islamist groups have always had formidable youth wings. During the revolutionary period, the Islamist political space fragmented. Today it still includes the largest number of active opponents to the Egyptian regime, although many of those activists are young Muslim Brotherhood members calling for Morsi’s reinstatement. They are increasingly isolated not only by the state, but from revolutionary movements who view Morsi’s autocratic tenure as a betrayal.

Yet a principled group of former Muslim Brotherhood members forms one of the most interesting revolutionary cohorts. Hundreds of young men and women who were among the elite of the Brotherhood’s official youth movement defied their hierarchical organization bosses and took part in the original Jan. 25 uprising in 2011. Most of them believed the Brotherhood should stay out of politics and remain a social and religious organization. These were pious and committed Islamic youth who believed in a secular, pluralistic state. Three of them were founding members of the Revolutionary Youth Coalition; they were among the first Brotherhood youth officially expelled by the hierarchical Islamist group.

They founded a political party, the Egyptian Current, which failed to attract wide membership. Some of its members work as independent activists or have joined secular political parties. Many of its best-known leaders now work with Strong Egypt, the political party of an ex-Muslim Brotherhood leader and presidential candidate, Abdel Monem Aboul Fotouh. Strong Egypt has been one of the only political organizations to condemn authoritarianism quickly and consistently, whether practiced by liberal civilian politicians, Morsi or Sissi. It forms the only existing bridge between secular revolutionaries and the powerful Islamist bloc, which for now has distanced itself from a project of pluralism, reform or revolt.

But the distrust between the two camps runs too deep for the kind of cooperation it would take to effect meaningful change in Egypt, and continuing efforts to mediate between anti-regime revolutionaries and Islamists have failed so far. Moaz Abdel Kareem, a former Brother and Revolutionary Youth Coalition member, has been one of the most persistent advocates of secular-Islamist collaboration. “It is crazy to think we can have a revolution without the Islamists,” he told me recently over a water pipe in a cafe in Istanbul. “We need to start a dialogue and agree on things we can fight for.” His own predicament suggests the impossibility of unity now; his old Islamist colleagues reject him as far too secular, while his revolutionary colleagues suspect he’s still secretly a Muslim Brother.

Illustrating the divide, in late November, secular revolutionaries rebuffed a public call from the Brotherhood for “revolutionary unity.” An April 6 spokesperson told Mada Masr, an independent Egyptian publication, that his organization would never again trust the Islamists, while a member of Strong Egypt said it was waiting for the Brotherhood to revise it positions and prove it could “keep its word.” In a further illustration of the exclusion of political “youth” dynamism by established political players, the Muslim Brotherhood itself criticized its own young members for going too far in their efforts to forge a united front with secular activists. The Brotherhood’s paternalistic tone echoes that of first Mubarak and now Sissi, with its patronizing dismissal of youth politics as naive, subversive or outright traitorous.

Sissi is unlikely to address Egypt’s core failures: the collapsing economy, the utter lack of justice or rule of law and the smothering of political life. In Tahrir Square in 2011, many people told me they had finally been motivated to protest because the state “humiliated” them: It prevented them from supporting their families, and it didn’t allow them the slightest political voice. The implication is clear. A regime might be able to get away with corruption and misrule if it allows some democratic expression, or it might get away with oppression as long as it delivers basic quality of life. But it will have trouble keeping its population quiescent if it fails on both counts.

The Role of Youth Beyond Egypt

Beyond Egypt, the entire Arab state system has been called into question, which is why powerful vested interests from the Gulf monarchies to the region’s nationalist militaries have engaged so fully in what they rightly view as an existential struggle. Nearly every country in the region has responded to these profound forces, although it is still early in their historical lifespan. Each Arab state offers a model of how to crush, harness or coopt revolutionary energy.

Short of war, there are three general approaches. The first is to deploy a police state to marginalize revolutionary ideas; Egypt is the leading example, but Bahrain and to some extent Jordan have followed a similar approach. The second is to embrace revolutionary energy within the system and attempt a transition: Tunisia has done this most successfully, although at periods Yemen and Libya seemed to have managed some degree of systemic change. The third is to redirect or absorb the revolutionary energy with neither a frontal clash nor a sincere effort to respond to its demands: Lebanon is the quintessential master of this sort of twisted jujitsu approach, although its principles can be seen at work in the maneuvers of regimes in Morocco, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. A closer look at Tunisia and Lebanon, as alternatives to Egypt’s course, also highlights the problem with relying on youth as an organizing principle to explain Arab politics.

Tunisia, Model or Exception?

Increasingly, Tunisia seems like an outlier in the Arab world. Its peaceful uprising was disproportionately younger than Egypt’s, and it was quickly supported by key institutional players, including the military. The biggest political blocs, the Muslim Brothers and the secular trade unionists, managed to negotiate a consensual constitution and a balanced transitional government despite their divergent visions. Islamists voluntarily ceded power after losing in Tunisia’s second elections. Not everyone is satisfied, but none of the key constituencies profess to have been locked out of the political transition, in contrast to Egypt. Perhaps most important in the context of the current discussion is the fact that “youth” were not ghettoized, but rather dispersed across the spectrum of politics and civil society.

Tunisia is a small nation whose relative wealth and education levels make it hard to compare to other Arab countries. Yet activists elsewhere in the region have drawn some key lessons. Tunisia benefited from a balance of power that included trade unions with a sizable, organized following, and also from a wise provision in the transitional electoral system preventing the winning party from amassing an absolute parliamentary majority. The main parties engaged in sincere, if occasionally acrimonious, negotiations. Islamists repudiated violence committed by their supporters, while secularists have avoided the taint of military authoritarianism that has come to characterize so many of their Egyptian counterparts.

This is perhaps a result of the fact that, while in exile years before Tunisia’s uprising, Muslim Brotherhood leader Rachid Ghannouchi and liberal dissident Moncef Marzouki met regularly, despite their profound ideological differences. Their relationship produced a level of institutional trust during Tunisia’s initial transition period, when Marzouki was president and Ghannouchi’s party controlled the government.

The Lebanese Alternative

For better and often for worse, Lebanon’s muddle-through system of compromise and patronage has become a regional model. Once dismissed as dysfunctional and corrupt, Lebanon’s solution to its 1975-1991 civil war has come to be seen by many other regional actors as a lesser evil, often worth emulating. Iraq might have accelerated the path to sectarian civil war by adopting a Lebanon-style sectarian ethnic quota system, but many there still see “Lebanonization” as a palliative and a preferable alternative to a bloodbath. Syrian activists who in 2011 swore they would never be “another Lebanon” now tell me that ending up like Lebanon after a decade of fighting might be the best hope they’ve got.

Lebanon’s volatile stalemate has staved off civil war and internal political revolt despite myriad systemic failures to address the concerns of ordinary citizens, especially unemployed or underemployed youth. In this, Lebanon might once again suggest a somewhat distasteful workaround.

Interestingly, no substantive youth or revolutionary or reform movement has emerged in Lebanon since the Arab Spring uprisings. Polling and anecdotal evidence suggest that the majority of Lebanese resent the spoils system of governance, controlled by the same major warlords who have dominated politics since the civil war. Yet their economic energy has been dissipated, either absorbed into the corrupt spoils system at home or dispersed into Lebanon’s vast diaspora, the proceeds from which prop up the country’s crippled economy.

Youth are freer in Lebanon than anywhere else in the Arab world to engage in cultural activity, although state security censors still carefully police the boundaries of free expression to silence radical critiques of the power structure. But that freedom doesn’t extend to politics. Young Lebanese are free to harness their political energy into the vibrant youth wings of the existing political parties, but not to challenge the status quo. All the major factions have intricate institutions to tap into youthful energy, including scouts, paramilitaries, social clubs, student council elections, fundraising work and ultimately party membership. Opportunities for political participation are limited to the existing sectarian parties.

One exception is the on-again, off-again movement in support of civil marriage, which remains elite, small and, while threatening to the sectarian spoils system, neither radically revolutionary nor inherently political. Presently, the civil marriage cause appears dormant. In times of heightened security fears, the demands of civil society in Lebanon tend to be drowned out, although a dedicated core group of civil society activists has persisted in the face of decades of pressure and ups and downs.

Conclusion

The political movements that challenged the Arab world’s established order in 2010 and 2011 are still in the process of developing. Their ideas and platforms are inchoate, and their leaders and core members are often under attack. In multiple countries, including Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Bahrain, proponents of even nonviolent incremental reform have been subject to terrifying levels of state violence. Elsewhere they have been systematically but less bloodily silenced or co-opted, including in Jordan, Qatar, the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

But it seems obvious that these movements are not going away, just as the Muslim Brotherhood, with its compelling ideology and disciplined organization, has never disappeared—despite repeated attempts at state-sponsored eradication—since its founding in 1928.

The great energy and aspirations that drove the revolts haven’t disappeared, even if the revolutionary leaders in Egypt have been marginalized for now. There on the margins, they are still working.

Kamel has concluded that the fault lies not with Egypt’s stars, but its citizens. “We have fought four regimes in a row, but most of the people of Egypt are not with us,” he told me this fall. “The problem in Egypt now is not the regimes. It is the people. We have to convince them.”

Some still believe that Sissi’s overreach will drive people together again, just like Mubarak’s abuse of power did in January 2011. “The Mubarak verdict shocked people,” Abdelkareem, the ex-Muslim Brother and Egyptian Current founder currently in exile, told me. “Now the youth are starting to cooperate again.”

Throughout the region, the same force that drove the uprisings has been redirected. Some of it simmers out of sight. Some of it has poured into the call for violent takfiri jihad in Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Egypt and perhaps elsewhere. Some of it has flowed into the quiet, continuing organizing of the political parties, youth movements and civil society groups that challenged status quo power. In Egypt, Sissi’s regime will either have to address these aspirations or fight a constant rear-guard war against dissent. The harder it fights, the more dissenters it will find.

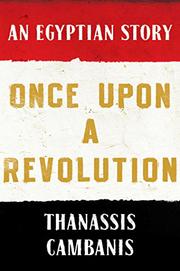

Another review out in Publisher’s Weekly of Once Upon a Revolution.

ONCE UPON A REVOLUTION

As the heady days of revolution in Tahrir Square recede further into the past, liberal democracy in Egypt seems increasingly like a pipe dream. Beirut-based journalist Cambanis (A Privilege to Die) follows two leaders of the uprising from the beginnings of their political involvement to the military coup that overthrew Mohamed Morsi. Basem, an unassuming architect, becomes one of the few liberal members of parliament, while Moaz, a Muslim Brother, grows increasingly disenchanted with political Islam. Cambanis eloquently describes post-Mubarak Egypt and the “chaos coursing below the surface, but open conflict still just over the horizon,” as well as the “inability of secular and liberal forces to unify and organize,” which left the political field open to the military apparatus and the secretive Islamists. Crushed by arbitrary military edicts and ascendant puritanism, Egypt’s nascent civil society stalled and sputtered while its freewheeling press degenerated into “a brew of lies, delusion, paranoia, and justification.” The people Cambanis shadows never lose hope, exactly, but he makes clear that they feel as if they are spitting into the wind, struggling to enunciate what the revolution accomplished. Agent: Wendy Strothman, Strothman Agency. (Feb.)

Middle East reporter Cambanis, who writes the “Internationalist” column for the Boston Globe and regularly contributes to the New York Times, offers a gripping portrayal of the forces that led to the eruption in Tahrir Square in Egypt on January 25, 2011. His reporting and analysis also move out from that event, considering a revolution that has not yet ended. He compares this revolution to the French Revolution, a long time coming and a long time continuing. Cambanis’ in-depth examination started, he says, with his on-the-ground reporting during the uprising, finding people in the square who were willing to continue to talk with him. The richness of his reporting informs his book, but it is the narrative nonfiction frame that humanizes the account and makes it more accessible. He focuses on two unlikely revolutionaries: Basem Kamel, a middle-class architect who came late to politics at 40, and Moaz Abdelkarim, a pharmacist and career activist. By tracing Kamel’s and Abdelkarim’s varying backgrounds, Cambanis manages both to give readers two insiders’ views of Egypt in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and to trace the origins of Tahrir Square and its ripples. Cambanis is master of the compelling detail: for example, in relating that Kamel was born in 1937, he notes that this was the year King Farouk I was crowned, a king who ate oysters by the hundred in his palace while his people endured WWII bombings. Wonderfully readable and insightful.

— Connie Fletcher

[Original here.]

KENNY KATOMBE/REUTERS/CORBIS

Soldiers from the United Nations intervention brigade in Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2013.

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section, November 28, 2014.]

MASISI, Democratic Republic of Congo—The massive peacekeeping effort undertaken here over the past 18 months hasn’t done much to slow the bloodshed in this central African nation. But it just might have destroyed a bold and hopeful new idea about how much the United Nations can accomplish.

Since Congo’s civil war broke out in 1994, it has become the world’s deadliest conflict, pitting neighboring governments and dozens of local warlords in a free-for-all over the prodigious profits to be made in eastern Congo’s mines. According to demographers, 5.4 million Congolese died during just one stretch from 1998 to 2006.

Fed up with the ineffectiveness of its traditional approach to peacekeeping, the United Nations Security Council decided last year to scrap its policy of firing only in self-defense. Instead, it launched a remarkable experiment: its first-ever “force intervention brigade,” a fully armed fighting unit to hunt down and stop predatory militias.

The goal was to put teeth in the UN’s promise to protect civilians in war zones. But after one early success routing the largest antigovernment militia, the brigade’s promise has faltered. The remaining militias have proved far harder to suppress, with foreign backers and sympathetic local supporters. And to some observers, the brigade has turned the United Nations into just another army in a war with too many armies already, helping hand territory over to a Congolese government that behaves just as badly as the militias it replaces.

For Congo, the failure of this experiment would mark a tragedy in a region already exhausted by tragedy. For the world at large, the test comes at a pivotal moment for the idea of international peacekeeping itself—a concept that is under increasing scrutiny from the nations upon whose money, troops, and political support its existence depends.

This year, the UN is taking a hard look at all its peacekeeping operations, trying to rethink how, and when, it should try to intervene in violent conflicts. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, who normally has a reputation for avoiding conflict even within his own bureaucracy, called this summer for a formal review of peacekeeping, describing a crisis brought on by interventions in complex civil wars “where there is no peace to keep.” Congo is being watched closely, and observers are skeptical that the outcome there will be encouraging.

“Is this the future? I’d say no,” says retired Major General Patrick Cammaert, who commanded UN peacekeepers for decades, including in Congo, and who now writes about the endemic problems of peacekeeping. “What more can the international community do?” Cammaert asks. “That’s the frustrating question.”

He’s contributing to a debate that has erupted among experts who want the UN to do better in the world’s bleakest war zones. Some are convinced it only requires more resources and effort. Others, however, have come to believe that the best we can do is to drastically reduce expectations of how much the international community can help.

IN A SENSE, the experiment in Congo exposes a contradiction wound into the UN’s very DNA. One founding principle of the UN was neutrality: that it could be an outside arbiter, swooping in to resolve regional conflicts without preference for one side or the other. Another principle was humanitarianism—helping vulnerable civilians and children, through intervention if necessary.

Its architects, determined to prevent another global conflict like World War II, gave the UN the power to dispatch peacekeepers who could monitor cease-fires and truce lines, protect refugees, even end wars. They didn’t imagine how profoundly the principles of neutrality and humanitarianism might start to conflict, as states and nonstate actors fought complex multiplayer wars that blurred traditional categories.

KENNY KATOMBE/REUTERS/CORBIS

UN peacekeepers with weapons recovered from militants in Congo in May.

Ironically, it was Congo that handed the UN its first major peacekeeping defeat in 1960. After a skirmish between UN troops and secessionists left hundreds of civilians dead, Western superpowers claimed the UN soldiers had acted beyond their orders, while the Soviet Union angrily accused the United States of supporting the assassination of Congo’s pro-independence prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. Compromised by political rivalries, the mission was effectively put into deep freeze until its official closure in 1964.

The UN stayed away from such controversial engagements until the Cold War had ended. In the 1990s, it began to venture again into complex civil wars. Peacekeepers were armed, often with top-of-the-line military equipment, but usually stayed out of the fray, like referees during a hockey brawl.

The failures of this approach mounted quickly and painfully. International peacekeepers were humiliatingly sidelined during the 1990s genocides of Rwanda and Bosnia. Hundreds of lightly armed UN peacekeepers were even taken hostage in Bosnia and used as bargaining chips by warlords. In Rwanda, the UN commander presciently warned of the coming genocide—and was ordered not to take any action to try to prevent it. Peacekeepers proved equally ineffective in Somalia.

Spurred by those failures, thinkers and policy makers began to push for a more muscular approach, giving rise to the somewhat paradoxical idea of “humanitarian intervention,” an anodyne term for the use of military force to help people and restore peace. Its supporters believed that in some wars, especially when governments or militias weren’t directly fighting each other but were instead killing civilians, neutrality no longer made sense. To end a civil war, it might be necessary to pick a side and help it prevail.

Congo became the lab for this new vision in 2012. After a relative calm of several years, the civil war had ramped up once again. The Rwandan-backed M23 militia was sweeping through the eastern provinces; warlords engaged in mass rape and murder while seizing control of the diamond trade and eastern Congo’s profitable coltan mines. Millions of civilians were displaced, again and again, in a shockingly poor and undeveloped state where it sometimes takes an entire day over rutted muddy tracks, on foot or motorcycle, to reach a nearby clinic or market town. Hundreds of militias vied for control of sometimes tiny areas. In what looked like a replay of past humiliations in Bosnia and Rwanda, M23 conquered even the city of Goma, where the UN had a headquarters and massive operation.

The embarrassment this time was a catalyst. The major powers at the UN and in Africa agreed they had to do more, and came up with the force intervention brigade, approved in March 2013.

THE PEACEKEEPERS in the UN stabilization mission—known by the acronym MONUSCO—wear the standard UN blue helmets and insignia, but there the resemblance to previous UN missions ends. Its highly trained infantry troops, from a variety of African states, are led by South African soldiers. They track Congolese militias using drones and the kind of surveillance technology that US special forces use to pursue Al Qaeda, swooping in the from the air to disarm or kill them. When civilians seek protection on UN bases, the peacekeepers go after the militias who threaten them. They pursue enemy fighters deep into the jungle.

In certain respects, the effort is working. During its first year, MONUSCO’s crack intervention brigade successfully routed M23, driving its leaders into exile or arresting them, and helping the Congolese government disarm or absorb most of its gunmen. It has presided over the restoration of a tenuous calm in places like Masisi, where farmers have resumed grazing profitable herds in the grassy hills after decades when violence made agriculture impossible. Motorcycle taxis ply roads that just a year ago were too dangerous to traverse. Commerce is haltingly returning to many villages, and some of the millions of displaced people are returning home.

But that’s where the first problem arises. The UN has chosen sides, which means supporting Congo’s current government. When the UN troops finish, they turn the cleared areas over the Congolese Army. Local residents frequently complain that these forces subject them to another wave of the same violence they experienced under militia rule. For residents mugged and shot by marauding gunmen, it makes no difference whether the overlords wear the insignia of a warlord’s militia or of the government. The government pressures the UN to criticize only the rebels; in October, it expelled the UN mission’s top human rights official after he released a report on the national police force’s abuses.

Meanwhile, dozens of militias are proving harder to dislodge. Local supporters of one formidable militia, backed by Uganda, staged demonstrations outside UN facilities this month against international efforts to drive it out of the northeast Congo. And there are policy thinkers who believe that the UN’s new approach makes it a legitimate military target. A report released this month by the International Peace Institute, a New York think tank, argues that the UN Congo mission’s aggressive mandate means that under international law, its “peacekeepers” no longer enjoy the legal protections that normally cover UN personnel.

The new approach has also split the UN and the peacekeeping world by creating fears that it might endanger humanitarian aid workers, from both the UN and unrelated nongovernmental organizations, who normally rely on the protection of neutrality. My own trip to Masisi in September took place under the auspices of the aid group Doctors Without Borders, whose volunteers and local staff expressed exactly this worry. So far, it appears that local antigovernment warlords haven’t turned against the group. But as I interviewed villagers, it became clear that plenty of them mistakenly believed that Doctors Without Borders was part of the UN.

AS WITH MOST OF THE UN’S most difficult missions, there is no end game for the Congo intervention. Peacekeepers were first deployed in 1999, and since then there have been many rounds of political negotiations involving the government, the rebels, and neighboring African countries. MONUSCO’s intervention brigade was deployed to support this vague and open-ended negotiation process, and thus has no stated timetable to leave the country.

To many, its failure would represent a particular disappointment. In a certain light, the brigade represents the UN and the Western powers at their most flexible and creative, trying to combine military might with a genuine commitment to the relief of suffering.

Chastened or emboldened by the lessons of Congo, UN leaders, the nations that pay for peacekeeping missions (led by the United States and Japan), and experts in the field are scrambling for new ideas for interventions that work—or whose failure or success can even be determined. Some experts now suggest that it would be wiser to embrace something more like “conflict management” than “conflict resolution,” an acceptance that outside powers can help save lives, but never actually end a civil war. Others argue for more investment on the political side, to force peace accords.

Richard Gowan, a peacekeeping expert at New York University, believes the international community should pick its shots—“Go big or go home,” he says—and stay away from incremental interventions that prolong conflict without resolving it.

Retired UN official Michael von den Schulenburg has worked with UN peacekeeping missions in Iraq, Afghanistan, Sierra Leone, and other hot spots and emerged as one of the system’s biggest critics, believing that Western powers have gotten addicted to the notion that there are military shortcuts to peace. “Peacebuilding is essentially cheating history. Look at our own states—our borders, what language we speak, which ethnic community predominates—it was always a bloody affair that went on for hundreds of years,” he says. “Now we want to solve these conflicts in 10 years.” He suggests dispensing with most peacekeeping altogether, and instead sending civilians to complicated war zones, in the full knowledge that they might be able to address small problems but not the big ones.

Slightly more optimistic is Severine Autesserre, a Barnard College political scientist who has spent years analyzing the dynamics and history of the Congo conflict. She embarked on a field study of all the reasons why foreign peacekeepers were destined to failure, and emerged with the opposite conclusion. In the book “Peaceland,” published this summer, she argues that through hundreds of minor, incremental improvements, the international community could dramatically boost the quality of life in conflict zones like those in Congo, thereby getting better value out of the troops it dispatches as peacekeepers.

If there is a lesson in the UN’s sporadic attempts to put weight behind its peacekeeping, it comes down to this: No outside power, not even an international mission blessed with moral authority and big guns, can unilaterally impose peace on a fractious war zone. An intractable stew of warlords, propped up by foreign states or nefarious funding networks, and a corrupt, authoritarian government prone to human rights abuses: This could easily describe Congo today, or Sudan, Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan. The West has tried all manner of approaches, from containment to invasion and occupation to staying out of it. That none of these tactics has reliably worked doesn’t mean that we should do nothing. But it does mean that whatever we do try is unlikely to bring a prompt end to the violence. It might, at best, save a few lives.

Thanassis Cambanis, a fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author of the forthcoming “Once Upon a Revolution: An Egyptian Story.” He is an Ideas columnist and blogs at thanassiscambanis.com.

The first review, from Kirkus, of my forthcoming Egypt book is out. I’m excited to imagine people reading this story from the Egyptian revolution.

Smart, troubling study of the events surrounding Tahrir Square and their aftermath.

That Cairo landmark is a metonym. As journalist/historian Cambanis (A Privilege to Die: Inside Hezbollah’s Legions and Their Endless War Against Israel, 2010) records in this lucid account of the Egyptian uprising, strategists of the opposition spent much time figuring out just where they could organize protests without being quashed by the country’s well-organized military, setting some of the early demonstrations and meetings in places “where the streets were too narrow for police trucks and water cannons” until momentum grew. It didn’t take long for the revolt to sweep the country, with its crowning day on Jan. 25, 2011. Cambanis profiles ordinary Egyptians who rose up against the Mubarak regime, some out of support for the Islamist cause, others in the hope of secular democracy. Their political divide runs deep. As the author writes of one key actor, “El-Shater didn’t seem to understand how much the liberals hated the Islamists, and how much the revolutionary Islamist youth mistrusted the Brotherhood leadership, himself included.” It is for that reason that the revolution—which, Cambanis reminds us, necessarily involves tumult and violence—remains incomplete. “I fell in love with the Tahrir Revolution,” he writes, “but this love didn’t blind me to its faults.” Still, to judge by this account, those faults are fewer than those of the previous regime, which leaves some hope that the people of Egypt are headed in the right direction—even if the Muslim Brotherhood soon “exposed itself as power hungry and eager to use violent tools of repression to silence opponents.”

That Cairo landmark is a metonym. As journalist/historian Cambanis (A Privilege to Die: Inside Hezbollah’s Legions and Their Endless War Against Israel, 2010) records in this lucid account of the Egyptian uprising, strategists of the opposition spent much time figuring out just where they could organize protests without being quashed by the country’s well-organized military, setting some of the early demonstrations and meetings in places “where the streets were too narrow for police trucks and water cannons” until momentum grew. It didn’t take long for the revolt to sweep the country, with its crowning day on Jan. 25, 2011. Cambanis profiles ordinary Egyptians who rose up against the Mubarak regime, some out of support for the Islamist cause, others in the hope of secular democracy. Their political divide runs deep. As the author writes of one key actor, “El-Shater didn’t seem to understand how much the liberals hated the Islamists, and how much the revolutionary Islamist youth mistrusted the Brotherhood leadership, himself included.” It is for that reason that the revolution—which, Cambanis reminds us, necessarily involves tumult and violence—remains incomplete. “I fell in love with the Tahrir Revolution,” he writes, “but this love didn’t blind me to its faults.” Still, to judge by this account, those faults are fewer than those of the previous regime, which leaves some hope that the people of Egypt are headed in the right direction—even if the Muslim Brotherhood soon “exposed itself as power hungry and eager to use violent tools of repression to silence opponents.”

A clear exposition and analysis of complex, swiftly changing events. The book gives readers cause to understand why we might support regime change in the Middle East, even if it brings instability and incoherence.

[Originally published in The Boston Globe.]

THE INTERNATIONALIST

US NATIONAL ARCHIVES

The gas crisis of the 1970s left many motorists stranded.

THE GLOBAL energy market can be a scary place for America. For decades, one of the biggest reasons has been the cartel known as OPEC.

Saudi Arabia and the 11 other nations that make up the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries collude openly, setting production limits and shaping the world oil market in their interests. Concerns about OPEC have driven American energy policy ever since a devastating six-month embargo by Arab oil producers in 1973 plunged the nation into recession and seared the four-letter acronym into the national consciousness.

Today the group still holds 80 percent of world oil reserves; ambassadors from the most powerful economies in the world attend its biannual meetings with deference, and dangle aid and other enticements in the hopes of winning OPEC’s allegiance. With American antagonists like Iran and Venezuela in its membership, OPEC amplifies the ability of relatively small countries to buck the desires of Washington.

But a closer look at OPEC’s real influence over the oil market suggests that we’re making a huge mistake about its global power, says Brown University political scientist Jeff Colgan. A specialist in oil and global conflict, Colgan tracked almost three decades of oil production data and compared it to official OPEC policy, which sets quotas for member countries. What he found surprised him: OPEC’s decisions were all but irrelevant.

As formidable as OPEC is seen to be, its members appeared to produce whatever they felt like, regardless of official policy; Colgan found that OPEC decisions weren’t actually affecting world oil supplies, or world oil prices. The group seemed unable to control its members or accomplish the one thing that even its detractors might appreciate: bring stability to the market.

“It drives me nuts,” Colgan says. “Washington spends bandwidth on OPEC that could be better dedicated to something else.”

Colgan’s research, published this summer, made a splash within the small circle of OPEC scholars, and even his critics concede that his findings require a reassessment of our understanding of the cartel. His thinking has yet to trigger policy changes, however. Although skepticism about OPEC has been rising—just last week, New York Times columnist Joe Nocera wrote about a 2013 Foreign Policy article titled “The End of OPEC”—most policy makers and academics still consider OPEC the key player in world energy markets, and the only one in a position to unilaterally disrupt the global flow of petrochemicals.

If Colgan is right, the implications go beyond OPEC: They suggest that petroleum is not the global bugaboo that many politicians and policy makers think. In this argument, Colgan has company: His findings echo earlier research suggesting that today’s American economy is no longer vulnerable to shocks in oil prices, or temporary supply disruptions caused by Middle Eastern wars.

His meticulous research suggests that OPEC is a sort of high-level con, which awards its member states unwarranted influence, wastes US time and energy, and distorts our energy policy and even our military priorities. An honest reckoning of power in the oil market might not only lead the United States to fear OPEC less, but even to behave a little more like it.

WHEN OPEC was formed in 1960, the oil industry was dominated by a different cartel. It was called the “Seven Sisters,” and was made up of western companies. Many of them have changed their names since then but are still industry giants, like ExxonMobil, BP, and Royal Dutch Shell.

The developing countries that actually held the world’s oil reserves wanted more clout. Saudi Arabia, which had the world’s largest and most accessible oil fields, was joined by four other founding members: Kuwait, Iraq, Iran, and Venezuela. Soon, nine more nations joined the group and opened a headquarters in 1965 in Vienna, the home of other important international institutions like the International Atomic Energy Association.

OPEC became a household name after the infamous oil embargo of 1973, which left a lasting psychological imprint on Americans. Gas stations closed on Sundays. Customers waited in interminable lines for their ration. Homeowners and businesses couldn’t afford to leave their heaters running at full blast throughout the winter. The economy went into a tailspin.

Forgotten in the bitter memory is that the embargo wasn’t actually imposed by OPEC, but by the Arab members of the cartel, along with Egypt, Syria, and Tunisia, in retaliation for America’s support for Israel in the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War. That distinction was lost, and policy makers ever since have railed against the dangers of dependence on OPEC oil. The legacy of the oil embargo drives American diplomacy, the rules governing worldwide oil contracts, and even the US case for hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which contends that the political benefits of “energy independence” outweigh fracking’s environmental and economic drawbacks.

DAVID BUTLER/GLOBE STAFF

Today, economists point out, the world energy market is far more integrated and interdependent than it was in 1973, when most oil was bought and sold in bulky, long-term contracts that made it hard for the market to quickly adjust to any change in supply.

Now producers need the profits as much as consumers need the gas. And despite the size of OPEC’s reserves—half of which are held by just two countries, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela—oil production is far more widely spread out than it used to be. Countries like the United States, Canada, and Mexico can satisfy a great deal of short-term demand even if their supplies will run low in a few decades. (In fact, the recent surge in US oil production last year made it the world’s largest oil producer, though its reserves are limited and the extraction process is only profitable when oil prices are high.) Oil is now bought and sold in a market that changes daily, so if one supply suddenly goes offline—like the oil industries of Libya and Iraq during various points of the last decade’s turmoil—other countries can step in to fill the gap in a matter of days.

Political scientists and economists have explored OPEC’s efficacy in multiple papers over the years, and almost all of them have concluded that even if it doesn’t function as a seamless cartel, it is the single most pivotal factor in setting global oil prices. It is this consensus that Colgan’s research punctures. He looked at official quotas since 1982, and found that OPEC member countries cheat an astonishing 96 percent of the time, pumping more than their permitted quota. He created a mathematical model to predict how much oil each country would produce if it were not constrained by the cartel’s quotas, and he found that when it came to a country’s oil production patterns, it didn’t seem to matter whether it was in OPEC or not. New members didn’t reduce production when they joined OPEC, and quota changes didn’t affect production levels.

Despite its reputation, Colgan found, OPEC simply doesn’t fit the definition of an effective cartel. Saudi Arabia—the sole producer with the spare capacity huge enough to unilaterally alter world supplies—floods the market or slashes capacity to suit its own needs, as it did in 2008 and is threatening to do again today in order to drive US fracking companies out of business. Almost all of the time, other OPEC members pumped as much as they could, whether prices were high or low.

Michael Levi, an energy and oil expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, acknowledges Colgan’s point that OPEC’s control of production and prices is not absolute, but believes he’s going too far in calling it powerless; cartels by definition aren’t transparent, and OPEC might still wield plenty of influence over member behavior. “It would be awfully unwise for policy makers or market participants to quickly flip to an equally over-confident belief that OPEC doesn’t matter,” he says.

American politics pretty much guarantees they won’t flip soon: In today’s debate over whether the United States should export its own oil, it’s still OPEC whose wrath the White House fears, rather than the more likely retaliation it might face from individual countries like Saudi Arabia. And OPEC is a convenient punching bag on Capitol Hill: Since 1999, the US Congress has introduced no fewer than 15 versions of a “NOPEC” bill, which would require the government to punish members of the international oil cartel. All the bills have failed, but they attract high-profile support. When they were senators, both Barack Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton voted for NOPEC bills.

COLGAN CALLS the cartel’s reputation a “rational myth”—a made-up story perpetuated because it serves an interest. OPEC initially was founded to control the oil market, but by the time member countries realized it didn’t, they were reaping too many political benefits from OPEC’s perceived clout to dissolve the organization.

DAVID BUTLER/GLOBE STAFF

OPEC membership has unquestionable benefits on the world stage: Colgan measured the number of ambassadors to members and found that joining OPEC provides a noticeable bump in foreign missions. When countries like the United States are worried about global oil production levels, or prices, they make pleas to the biggest player in the market, and that means OPEC.

For America, though, the fear of OPEC has costs. For one thing, it means the United States misses opportunities to exploit the fissures between OPEC countries, which often have diametrically opposed interests (today for instance, Iran wants low production and high prices to help it survive sanctions; Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, wants low prices in order to regain its dominant market share). Since the 1973 embargo, almost every aspect of US energy policy appears designed to protect consumers and the economy from a price shock or supply disruption, even though today the United States is itself an oil giant that gets rich off the sale of oil and gas.

There are real lessons to take from OPEC as we have long understood it—and from comparing countries that have wisely managed their oil wealth, like Norway, to those that have used it to mask domestic stagnation, like Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Whether a country is an oil exporter or importer, it’s a smart investment to reduce consumption and diversify sources as much as possible, including toward wind and solar power. The most impressive oil exporters husband their energy profits, treating them as a limited windfall rather than a sustainable and permanent revenue stream.

The experience of the OPEC countries also highlights the tension between gas pricing, environmental stewardship, and national interests in ways that are increasingly relevant for the United States. Traditionally, low fuel prices have boosted the US economy, but increased pollution and dependency. High gas prices are good for an energy policy built around restraint—less consumption, less pollution—and now they actually have an economic benefit as well, boosting the burgeoning domestic oil sector.

Even if OPEC is not the power we thought, the group’s recent history has lessons for us, most simply that it’s not a bad idea to maximize the profits you can draw from your limited reserves of underground oil. Pump less to drive prices up, pump more when you need cash (or extra energy), and worry less about the global economy than about your own bottom line and long-term fiscal health. That might be the formula of a villainous cartel—or just good business sense for a nation.

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

THE INTERNATIONALIST

THE RISE OF the Islamic State, also known as ISIS, took much of the world by surprise. When it swept into Mosul and swiftly turned most of northern Iraq into the cornerstone of a regressive new caliphate, the organization was an unknown quantity even to many professional analysts, reporters, and policy makers.

But very quickly, some new go-to sources emerged. Two of them were Twitter streams that unleashed a torrent of crucial links and information. They revealed the depth of the group’s beef with Al Qaeda, which ISIS seemed to consider a higher-priority enemy than even the unbelievers it had executed. They published extracts of the recruitment literature the group had used to lure Western fighters, and shared some of its previously unknown ideological treatises. They brought to light the extensive ISIS propaganda network, while countering some of its claims. Since the United States declared war on the group and started bombing sites in Iraq and Syria, the sources have continued their indispensable work, providing details on little known targets like the “Khorasan Group” and the reaction of ISIS to the American strikes.

These gushers of highly useful information were not coming from inside a formal intelligence operation, or even from the Middle East. Instead, they were being run by ordinary American civilians out of their own homes. One was J.M. Berger, 47, a former journalist turned freelance social network analyst and extremism expert, who published scoop after scoop from his home office in Cambridge. The other was Aaron Zelin, a 26-year-old graduate student in Washington, D.C., who made his name with a blog called Jihadology. The two researchers had been mining the jihadi Internet for years, tracking it with a combination of old-school scholarship and new purpose-built apps.

Zelin and Berger are something new in the intelligence world: part of an emerging breed of online jihadi-hunters who have done pathbreaking work, often independently of government and big media outlets, on a shoestring budget. Numbering less than a dozen, they have earned their reputations over the past four years by being the first to report key developments later confirmed by mainstream research and reporting—such as the split between the Islamic State and Al Qaeda, the burst of jihadi recruitment in the West, and the entry of Hezbollah into the Syrian battle. The meteoric rise of ISIS has been a catalyzing moment for these analysts, pushing them into the spotlight as one of the most important sources of information and context.

These freelance online analysts offer a counterweight to decentralized militant groups. Since the Sept. 11 attacks, America has struggled to grapple with nimble, stateless groups that can move faster than national governments. But the same tools that militant groups and jihadis have exploited so effectively cut both ways. Those who want to shut down violent networks have a new weapon in intelligence-gatherers who operate outside traditional channels and aren’t hindered by bureaucratic myopia.

Despite some friction, their research is forcing the academic and intelligence establishment to treat Twitter, Facebook, and other social media as important sources of data. The small world of social media analysts who have established reliable reputations over time, relying on information freely available in the public domain, implicitly challenges the US government’s claim that only massive, secret surveillance can penetrate jihadi networks.

“Some people say, ‘Who is this guy to be writing about this stuff?’” says Clint Watts, a former FBI agent who has developed an influential following for the analysis of global jihad that he writes after hours. Through Twitter, he’s been able to team up with dozens of experts who 15 years ago he wouldn’t have known how to contact. And through his blog, he’s found a high-level audience that government intelligence analysts could only dream of. “This is mostly a hobby for me,” he said. “The less involved I am in the terrorism analysis community, the more my posts get read.”

EONS AGO in Internet time, back in 2006, Hezbollah and Israel fought a quick and destructive war in Lebanon. I was one of the journalists who covered it on the front lines, and we struggled to report the precise nature of Hezbollah’s involvement. Hezbollah tried to obscure its hand, hiding the number of fighters under its command and even whether they were active in the war. It was rare to see a fighter in person at all, and those who were spotted often pretended to represent a local clan or a militia other than Hezbollah.

People guessed at the number of Hezbollah fighters killed, and ultimately had to rely on an unverifiable number issued by the party itself. It was the kind of information that watchers of the conflict had to resign themselves to never being able to know for sure.