Arrested Development: The Pentagon Going Forward

The Pentagon finally learned to embrace new ideas. Can its short-lived revolution in thinking survive the coming period of austerity and retrenchment? [Originally posted on The Blog of the Century.]

The American military has maintained global dominance in part by being all things to all people. Blessed with a Brobdingnagian budget, it has been able to prepare for all kinds of war, all at the same time. Faced now with cuts after a decade of open-handed war funding, the Pentagon has raised the alarm about readiness. The Joint Chiefs of Staff in a unanimous letter in January complained to the president that “we are on the brink of creating a hollow force.”

The debate over the size and mission of the military often obsesses about questions of degree: should the United States be able to fight two major wars at the same time? Should it design a force that can fight many small wars?

But this debate, driven by budget-hungry service chiefs and tradition-hemmed academics and think-tankers, might be ignoring a far more important turning point facing the Pentagon today, which has more to do with mindset than money. Can the Pentagon retain the one truly good thing it acquired along the way in the bungled war on terror, Afghanistan, and Iraq—a possibly short-lived ability to learn?

Fred Kaplan’s new book, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War, which I reviewed in the New York Times this Sunday, chronicles a chilling intellectual history of the officers who promoted counterinsurgency doctrine and eventually forced change among the Pentagon’s top brass. Kaplan is a skeptic, but his story reveals just how deeply hidebound the generals are, and how they were forced—through failure—to criticize themselves and adjust tactics.

Can this new mindset take root and become part of the Pentagon’s DNA, or is it destined to vanish as the generals who briefly dallied with self-awareness and adaptation now retrench around the common cause of budgetary self-preservation?

Listening to the current chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, isn’t reassuring. Half a decade ago in Baghdad he eschewed BS, acknowledging the burgeoning failure and once telling a group of us reporters bluntly that “there isn’t enough concrete in the hemisphere to make Baghdad safe.” Now he’s stumping for wild defense budgets based on a spurious claim that the world is more dangerous than ever before and that we face an infinite menu of threats. Dempsey’s about-face doesn’t bode well.

For all the pitfalls of the war on terror, a decade of coalition-building and counterinsurgency forced the military to adapt and open itself up to new methods with an alacrity not seen since World War II. It was a wrenching internal fight between rigid generals, abstract bureaucrats, and junior officers open to experimentation and self-criticism, which Kaplan documents in vivid detail.

In The Insurgents (published in January), Kaplan argues that the U.S. military, perhaps inadvertently, discovered on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan a new ability to learn. Now that the United States has moved away from those wars, Kaplan says, it is also throwing out what might be their only good legacy: imagination and flexibility in the Pentagon’s upper reaches.

His argument comes at a crucial time. President Obama last year ordered the Pentagon to cut off its budget for nation-building and long-term occupations of foreign lands—but he also instructed it to preserve the lessons it learned fighting counterinsurgencies in the Middle East. Many of the young officers who created a vogue around counterinsurgency in military circles grew just as dogmatic in their thinking as the older bureaucrats and officers who at first resisted new thinking, a sad process evident to any close observer of the slow failure of U.S. efforts in Afghanistan.

But they succeeded—at least in the last few years—at changing the military’s internal culture in ways far more consequential than the line item for a new bomber. They convinced the Pentagon to promote top generals who excelled in combat rather than those who had dutifully served in logistics and office posts. They reinvigorated the intellectual centers of military thinking, in particular the web of institutions from Fort Leavenworth to West Point that educate officers, write the military’s doctrine, and drive much of America’s strategic thinking. And they injected a strain of strikingly inventive utilitarianism—whatever works—into a vast defense bureaucracy that’s designed to protect fiefdoms rather than create new ideas.

Now, with the bloated war budgets ending and sequestration in site, a clear war of ideas is underway in the Pentagon: the old way, exemplified in the joint chiefs’ demand for big budgets, big weapons systems, and the same old lack of priorities, versus a fledgling new can-do culture that values the military’s ability to learn and adapt over its arsenal and size.

Let’s hope that creativity wins out. But I wouldn’t bet on it.

UPDATE: I debate The Insurgents and post-invasion Iraq with TCF fellow Michael Cohen. We’ll be on Bloggingheads TV on Wednesday.

How We Fight

Fred Kaplan’s Insurgents on David Petraeus

The American occupation of Iraq in its early years was a swamp of incompetence and self-delusion. The tales of hubris and reality-denial have already passed into folklore. Recent college graduates were tasked with rigging up a Western-style government. Some renegade military units blasted away at what they called “anti-Iraq Forces,” spurring an inchoate insurgency. Early on, Washington hailed the mess a glorious “mission accomplished.” Meanwhile, a “forgotten war” simmered to the east in Afghanistan. By the low standards of the time, common sense passed for great wisdom. Any American military officer willing to criticize his own tactics and question the viability of the mission brought a welcome breath of fresh air.

Most alarming was the atmosphere of intellectual dishonesty that swirled through the highest levels of America’s war on terror. The Pentagon banned American officers from using the word “insurgency” to describe the nationalist Iraqis who were killing them. The White House decided that if it refused to plan for an occupation, somehow the United States would slide off the hook for running Iraq. Ideas mattered, and many of the most egregious foul-ups of the era stemmed from abstract theories mindlessly applied to the real world.

There is no one better equipped to tell the story of those ideas — and their often hair-raising consequences — than Fred Kaplan, a rare combination of defense intellectual and pugnacious reporter. Kaplan writes Slate’s War Stories column, a must-read in security circles. He brings genuine expertise to his fine storytelling, with a doctorate from M.I.T., a government career in defense policy in the 1970s and three decades as a journalist. Kaplan knows the military world inside and out; better still, he has historical perspective. With “The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War,” he has written an authoritative, gripping and somewhat terrifying account of how the American military approached two major wars in the combustible Islamic world. He tells how it was grudgingly forced to adapt; how it then overreached; and how it now appears determined to discard as much as possible of what it learned and revert to its old ways.

Read the rest in The New York Times [subscription required].

What really drives civil wars?

Christia Fotini with a Syrian girl in a camp for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Syria in the village of Atmeh.

[Originally published in The Boston Globe.]

WHAT IS a civil war, really?

At one level the answer is obvious: an internal fight for control of a nation. But in the bloody conflicts that split modern states, our policy makers often understand something deeper to be at work. The vengeful slaughter that has ripped apart Bosnia, Rwanda, Syria, and Yemen is most often seen as the armed eruption of ancient and complex hatreds. Afghanistan is embroiled in a nearly impenetrable melee between Pashtuns and smaller ethnic groups, according to this thinking; Iraq is split by a long-suppressed Sunni-Shia feud. The coalitions fighting these wars are seen as motivated by the deepest sort of identity politics, ideologies concerned with group survival and the essence of who we are.

This view has long shaped America’s engagement with countries enmeshed in civil war. It is also wrong, argues Fotini Christia, an up-and-coming political scientist at MIT.

In a new book, “Alliance Formation in Civil Wars,” Christia marshals in-depth studies of the recent wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Bosnia, along with empirical data from 53 civil conflicts, to show that in one civil war after another, the factions behave less like enraged siblings and more like clinically rational actors, switching sides and making deals in pursuit of power. They might use compelling stories about religion or ethnicity to justify their decisions, but their real motives aren’t all that different from armies squaring off in any other kind of conflict.

How we understand civil wars matters. Most civil wars drag on until they’re resolved by a foreign power, which in this era almost always includes the United States. If she’s right, if we’re mistaken about what motivates the groups fighting in these internecine free-for-alls, we’re likely to misjudge our inevitable interventions—waiting too long, or guessing wrong about what to do.

***

CIVIL WARS ALWAYS have loomed large in the collective consciousness. Americans still debate theirs so vociferously that a blockbuster film about Abraham Lincoln feels topical 150 years after his death. Eastern Europe saw several years of ferocious killing in the round of civil wars that followed World War II.

Such wars have been understood as fights over differences that can’t be resolved any other way: fundamental questions of ideology, identity, creed. A disputed border can be redrawn; not so an ethnic grudge. In the last two decades, identity has become the preferred explanation for persistent conflicts around the world, from Chechnya to Armenia and Azerbaijan to cleavages between Muslims and Christians in Nigeria.

This thinking allows for a simple understanding, and conveniently limits the prospect for a solution. Any identity-based cleavage—Jew vs. Muslim, Bosnian vs. Serb, Catholic vs. Orthodox—is so profoundly personal as to be immutable. The conventional wisdom is best exemplified by a seminal 1996 paper by political scientist Chaim Kaufmann, “Possible and Impossible Solutions to Ethnic Civil Wars,” which argues that bitterly opposed populations will only stop fighting when separated from each other, preferably by a major natural barrier like a river or mountain range.

During the 1990s, this sort of ethnic determinism drove American policy toward Bosnia and Rwanda. It was popularized by Robert Kaplan’s book “Balkan Ghosts,” which was read in the Clinton White House and presented the wars in the former Yugoslavia as just the latest chapter in an insoluble, four-century ethnic feud. Like Kaufmann, Kaplan suggested that the grievances in civil wars could only be managed, never reconciled.

After 9/11, policy makers in Washington continued to view civil wars through this prism, talking about tribes and sects and ethnic groups rather than minority rights, systems of government, and resource-sharing. That view was so dominant that President Bush’s team insisted on designing Iraq’s first post-Saddam governing council with seats designated by sect and ethnicity, against the advice of Iraqis and foreign experts. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy as Iraq’s ethnic civil war peaked in 2006; things settled down only after death squads had cleansed most of Iraq’s mixed neighborhoods, turning the country into a patchwork of ethnically homogenous enclaves. Similarly, this thinking has shaped US policy in Afghanistan, where the military even sent anthropologists to help its troops understand the local culture that was considered the driving factor in the conflict.

Christia grew in up in the northern Greek city of Salonica in the 1990s, with the Bosnian war raging just over the border. “It was in our neighborhood and we discussed it vividly every night over dinner,” she says. The question of ethnicity seized her imagination: Were different peoples doomed to conflict by incompatible identities? Or were the decision-makers in civil wars working on a different calculus from their emotional followers? As a graduate student at Harvard, Christia flew to Afghanistan and tried to turn a dispassionate political scientist’s eye to the question of why warlords behave the way they do.

Christia spent years studying these warlords, the factional leaders in a civil war that broke out in the late 1970s. As a graduate student and later as a professor, she returned to Afghanistan to interview some of the nastiest war criminals in the country. She concluded that culture and identity, while important for their adherents, did not seem to factor into the motives of the warlords themselves, and specifically not in their choices of wartime allies. Despite the powerful rhetoric about ethnic alliances forged in blood, warlords repeatedly flipped and switched sides. They used the same language—about tribe, religion, or ethnicity—whether they were fighting yesterday’s foe or joining him.

If ethnicity, religion, and other markers of identity didn’t matter to warlords, Christia asked, what did? It turns out the answer was simple: power. After studying the cases of Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Iraq in intricate detail, Christia built a database of 53 conflicts to test whether her theory applied more widely. She ran regression analyses and showed that it did: Warlords adjusted their loyalties opportunistically, always angling for the best slice of the future government. It’s not quite as simple as siding with the presumed winner, she says: It’s picking the weakest likely winner, and therefore the one most likely to share power with an ally.

In this model of warlord behavior, the many factions in a civil war are less like Cain and Abel and more like the mafia families in “The Godfather” trilogy. Loyalties follow business interests, and business interests change; meanwhile, the talk about family and blood keeps the foot soldiers motivated. In Bosnia, one Muslim warlord joined forces with the Serbs after the Serbs’ horrific massacre of Muslims at Srebenica, and justified his switch by saying that the central government in Sarajevo was run by fanatics while he represented the true, moderate Islam. In case after case of intractable civil wars—Afghanistan, Lebanon, Iraq, the former Yugoslavia—Christia found similar patterns of fluid alliances.

“The elites make the decision, and then sell it to the people who follow them with whatever narrative sticks,” Christia said. “We’re both Christians? Or we’re both minorities? Or we’re both anti-communist? Whatever sticks.”

***

CHRISTIA’S WORK has been received with great interest, though not all her academic colleagues agree with her conclusions. Critics say identity is more important in civil wars than she gives it credit for, and we ignore it at our peril. Roger Petersen, an expert on ethnic war and Eastern Europe who is a colleague of Christia’s at MIT and supervised her dissertation, argues that in some conflicts, identity—ethnic, religious, or ideological—is truly the most important factor. Leaders might make a pact with the devil to survive, but once a conflict heads to its conclusion, irreconcilable conflicts often end with a fight to the death. Communists and nationalists fought for total victory in Eastern Europe’s civil wars, with no regard to their fleeting coalitions of opportunity against foreign occupiers during World War II. More recently, Bosnia’s war only ended after the country had split into ethnically cleansed cantons.

Christia acknowledges that her theory needs further testing to see if it applies in every case. She is currently studying how identity politics play out at most local level in present-day Syria and Yemen.

If it holds up, though, Christia’s research has direct bearing on how we ought to view the conflict today in a nation like Syria. The teetering dictatorship is the stronghold of the minority Allawite sect in a Sunni-majority nation. And leader Bashar Assad has rallied his constituents on sectarian grounds, saying his regime offers the only protection for Syria’s minorities against an increasingly Sunni uprising. But Syria’s rebellion comprises dozens of armed factions, and Christia suggests that these militants, which run the gamut of ethnic and sectarian communities, will be swayed more by the prospect of power in a post-Assad Syria than by ethnic loyalty. That would mean the United States could win the loyalty of different fighting factions by ignoring who they are—Sunni, Kurd, secular, Armenian, Allawite—and by focusing instead on their willingness to side with America or international forces in exchange for guns, money, or promises of future political power.

For America, civil wars elsewhere in the world might seem like somebody else’s problem. But in reality we’re very likely to end up playing a role: Most civil wars don’t end without foreign intervention, and America is the lone global superpower, with huge sway at the United Nations. Christia suggests that Washington would do well to acknowledge early on that it will end up intervening in some form in any civil war that threatens a strategic interest. That doesn’t necessarily mean boots on the ground, but it means active funding of factions and shaping of the alliances that are doing the fighting. In a war like Syria’s, that means the United States has wasted precious time on the sidelines.

Despite her sustained look at the worst of human conflict, Christia says she considers herself an optimist: People spend most of their history peacefully coexisting with different groups, and only a tiny portion of the time fighting. And once civil wars do break out, the empirical evidence shows that hatreds aren’t eternal. “If identities mattered so much,” she says, “you wouldn’t see so much shifting around.”

What failed negotiations teach us

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

ROCKETS AND MORTARS have stopped flying over the border between Gaza and Israel, a temporary lull in one of the most intractable, hot-and-cold wars of our time. The hostilities of late November ended after negotiators for Hamas and Israel—who refused to talk face-to-face, preferring to send messages via Egyptian diplomats—agreed to a rudimentary cease-fire. Their tenuous accord has no enforcement mechanism and doesn’t even nod to discussing the festering problems that underlie the most recent crisis. Both sides say they expect another conflict; experience suggests it’s just a question of when.

Generations of negotiators have cut their teeth trying to forge a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians, and their failures are as varied as they are numerous: Camp David, Madrid, the Oslo Accords, Wye River, Taba, the Road Map. For diplomats and deal-makers around the world—even those with no particular stake in Middle East peace—Israel and Palestine have become the ultimate test of international negotiations.

For Guy Olivier Faure, a French sociologist who has dedicated his career to figuring out how to solve intractable international problems, they’re something else as well: an almost unparalleled trove of insights into how negotiations can go wrong.

For more than 20 years, Faure has studied not only what makes negotiations around the world succeed, but how they break down. From Israel and the Palestinians to the Biological Weapons Convention protocol to the ongoing talks about Iran’s nuclear program, it’s far more common for negotiations to fail than to work out. And it’s from these failures, Faure says, that we can harvest a more pragmatic idea of what we should be doing instead. “In order to not endlessly repeat the same mistakes, it is essential to understand their causes,” he says.

***

TODAY’S INTERNATIONAL order turns on successful negotiation. When we think about what’s right in the world, we’re often thinking about the results of agreements like the START treaties, which ended the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union; the Geneva Conventions, which govern the conduct of war; or even the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, drafted in 1948, which still underpins globalized free trade.

But in negotiations over the most vexing international problems—a hostage situation, a war between a central government and terrorist insurgents, a new multinational agreement—such successes are few and far between. Failure is the norm. Understandably, experts tend to focus on the wins. From US presidents to obscure third-party diplomats, negotiators pore over rare historical successes for tips rather than face the copious and dreary overall record.

Faure wants to change that focus. As an expert he straddles two worlds: He studies diplomacy academically as a sociologist at the Sorbonne, in Paris, and has also trained actual negotiators for decades, at the European Union, the World Trade Organization, and UN agencies. Over his career, he has produced 15 books spanning all the different theories behind negotiation, and ultimately concluded that negotiations that failed, or simply sputtered out inconclusively, were the most interesting. Each failure had multiple causes, but it was possible to compile a comprehensive list, and from that, consistent patterns.

“Unfinished Business” takes a look at what happened during a number of high-profile failures, and examines the underlying conditions of each set of talks: trust, cultural differences, psychology, the role of intermediaries, and outsiders who can derail negotiations or overload them with extraneous demands.

One of Faure’s insights concerns the mindset of negotiators—a factor negotiators themselves often believe is irrelevant, but which Faure and his colleagues believe can often determine the outcome. Incompatible values on the two sides of the table, he says, are much harder to bridge than practical differences, like an argument over a boundary or the mechanics of a cease-fire. As Faure says, “A quantity can be split, but not a value.” This is what Faure saw at work when the Palestinians and Israelis embarked on a rushed negotiation at the Egyptian seaside resort of Taba during Bill Clinton’s final month in office. The two sides had already reached an impasse at a lengthier negotiation in 2000 at Camp David. With the end of his presidency looming and Israeli elections coming up, Clinton summoned them back to the table for a no-nonsense session he hoped would bring speedy closure to disputes over borders, Jerusalem, and refugees. The Palestinians, however, felt that the two sides simply didn’t share the same view of justice and weren’t truly aiming at the same goal of two sovereign states—and so didn’t feel driven to make a deal. That mismatch of long-term beliefs, Faure says, doomed the talks.

There are other warning signs that emerge as patterns in failed talks. Time and again, parties embark on tough negotiations already convinced they will fail—a defeatism that becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy. In interviewing professional negotiators, Faure and his colleagues found that they often don’t pay that much attention to the practical aspects of how to run a negotiation—a surprising lapse.

Faure and his team have found that a well-planned process is one of the best predictors of success, and that many negotiations are terrible at it. When the European Union and the United States talked to Iran about its nuclear program, various European countries kept adding extraneous issues to the talks, for instance linking Iran’s behavior with nukes to existing trade agreements. The additions made the negotiations unwieldy, and provoked crises over matters peripheral to the actual subject. In the case of the mediation over Cyprus, the Greek and Turkish sides didn’t bother coming up with any tangible proposed solution to negotiate over, instead talking vaguely about a Swiss model. Negotiations failed in part because neither side knew what that would mean for Cyprus.

Ultimately, Faure argues, mistrust and inflexibility tangle up negotiators more than any other factor. Negotiators often end up demonizing the other side, and as a result might embark on a process that by its structure encourages failure. For instance, Israeli and Palestinian reliance on mediators to ferry messages—even between delegations in the same resort—maximizes misunderstandings and minimizes the possibility that either side will sense a genuine opening.

***

WHAT EMERGES FROM Faure’s work, overall, is that the outlook for negotiations is usually pretty bleak—certainly bleaker than Faure himself prefers to highlight. In some cases, he suggests that diplomats should put off an outright negotiation until they’ve dealt with gaps in trust and cultural communication, or until the conflict feels “ripe” for solution to the parties involved. There’s no point, he suggests, in embarking on a negotiation if all the stakeholders are convinced it’s a waste of time—indeed, a failed negotiation can sometimes exacerbate a problem.

The most promising scenarios occur when both sides are suffering under the status quo, which creates what social scientists call a “mutually hurting stalemate,” with soldiers or civilians dying on both sides, and a “mutually enticing opportunity” if there’s a peace agreement or a prisoner swap. In that case, a decent deal will give both sides a chance to genuinely improve their lot.

Unfortunately for the many whose hopes are riding on negotiations, the truly challenging international problems of our age don’t always come with a strong incentive to compromise. In military conflicts, there is little incentive to resolve matters when a conflict is lopsided in one side’s favor (Shia versus Sunni in Iraq, Israel versus Hamas, the Taliban versus the United States in Afghanistan). The same holds in broader international agreements: They’re complicated and intractable largely because the states involved are—no matter what they say—quite comfortable with the status quo. Think about climate change: The biggest gas-guzzlers and polluters, the ones whose assent matters the most for a carbon-reduction treaty, are often the last states that will pay the price for rising oceans. Meanwhile, the poorer nations whose populations are most at the mercy of sea levels or changing weather have little clout. Just as it’s easy for a relatively secure Israel to stand pat on the Palestinian question, there are few immediate consequences for the United States and China if they sit out climate talks.

It’s not all bleak news. Even in cases where negotiations appear hamstrung—like climate change and Palestine—there are, Faure points out, plenty of other reasons to continue negotiating. Negotiations are a form of diplomacy, dialogue, and recognition, and even in failure can serve some other interests of the parties involved. But—as the impressive historical record of failed international agreements shows—it’s naive to think that they will always yield a solution.

Where Hamas Goes From Here

Ismail Haniya delivers a speech after the conflict in Gaza. (Ahmed Zakot / Courtesy Reuters)

[Originally published in Foreign Affairs.]

Once again, Hamas has been spared from making the difficult political choice that face most resistance movements when they gain power: whether to focus on the fight or to govern. Since it won the Palestinian elections in 2006 and then took control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, Hamas has been free to pursue a middle course, resisting Israel while blaming its political failures on its cold war with Fatah and on Israel’s blockade. Now Hamas will tout the concessions it won from Israel last week — as part of the ceasefire, Israel agreed to open the border crossings to Gaza, suspend its military operations there, and end targeted killings — as proof that it should not give up fighting. Meanwhile, the outcome should be enough to buy Hamas cover for its poor record of governance and allow it to again defer making tough choices about statehood, negotiations, regional alliances, and military strategy. The group might even be able to use the momentum to supplant Fatah in the West Bank as it has done in Gaza.

Hamas’ recent advance won’t fully mask the organization’s central dilemma, nor will it cover internal rifts about how to solve it. In the American and Israeli media, portrayals of Hamas often focus heavily on the group’s commitment to eliminating the Jewish state. And certainly any fair study of the group should take into account that goal. Yet for Hamas, the end of Israel is more an ideological starting point than a practical program. And what comes after the starting point is unclear: Hamas has never developed a vision of what a resolution short of total victory might look like, nor has it spelled out an agenda for governing its own constituents, despite all these years in power. In part, that is because Hamas is a diffuse and contested movement, whose competing factions all work toward their own self-interest.

Hamas’ top political leadership used to operate out of Damascus but scattered to Cairo, Doha, and other Middle Eastern capitals this year as Syria descended into chaos. Since then, the exiled leadership has clashed publicly with Hamas’ Gaza-based leadership. Khaled Meshal, the organization’s main leader, now based Doha, and his cohort have generally allied with the Sunni Arab states over Iran, welcoming the rise of Islamists in Egypt, in Tunisia, and among the Syrian rebels. Meshal himself has publicly endorsed a truce with Israel based on Israel’s withdrawal to its 1967 borders. The rest of the exile-based leaders have also indicated their willingness to consider a truce, although they say they would consider the deal temporary and would not recognize Israel. Party in response to Hamas’ pragmatism, and partly in acceptance of the reality of the movement’s rising power. Arab leaders finally ended their informal boycott of Gaza, and, in recent months, the emir of Qatar and the prime minister of Egypt paid visits.

Yet the growing stature of Hamas might accentuate, rather than diffuse, the tensions between its exiled chiefs and its Gaza-based leadership. According to Mark Perry, a historian who follows Palestinian politics, Hamas’ prime minister, Ismail Haniya, has endorsed a close relationship with Iran. For his part, Haniya paid a warm visit to Tehran in February, provoking the ire of Arab leaders, who have since given him the cold shoulder, preferring instead to meet with other Hamas leaders. Haniya has expressed no interest in talking about a two state solution and overall, the rest of the Gaza-based leadership has simply grown more uncompromising under the Israeli blockade and now two lopsided wars. It prefers full-throated resistance to any political settlement.

It is unclear whether the differences presage an ideological split or are simply the result of two very different vantage points: inside Gaza, where the leaders have to worry about staying in power, and outside it, where the leaders worry about staying regionally relevant. So far, Hamas has seemed unable to address the issues that divide the two factions, which might explain why the movement has not selected a successor to Meshal, who was supposed to step down this spring. The sides do, of course, have lowest common denominators that hold them together: resistance as the primary avenue to winning Palestinian rights; gaining greater share of Palestinian leadership; and Islamism.

Since Hamas’ creation in 1987, it has tried to match Fatah’s strength. With that goal largely accomplished by 2007, it has moved on to pushing Fatah completely to the sidelines by maintaining a commitment to Islamism and opposition to the Jewish state. By contrast, Fatah has remained secular, and has even agreed to recognize Israel and to conduct an experiment in joint governance with it through the Palestinian Authority. Two decades into the Oslo process, Fatah has little to show for its efforts. Meanwhile, Hamas has not had to face Palestinian voters since 2006. Polling suggests that Palestinians — Gazans in particular — have lost patience with Hamas. But each conflict with Israel gives the movement a new lease on life.

As recently as last week, Israel was describing in breathless terms the latest tepid exploits of the smoky, aging leader of Fatah, Mahmoud Abbas, who is on the verge of obtaining non-member observer status at the United Nations. Israel’s foreign ministry was reportedly circulating policy options to deal with his gambit that included dismantling the Palestinian Authority and withholding its rightful tax revenues, which would effectively subject the West Bank to the same kind of isolation that Gaza has faced since Hamas took power. That would play directly to the long-term goals shared by Hamas’ leaders in Gaza as well as those in exile: to take over from Fatah the role of primary representative of all Palestinians.

What is more, developments in the region have boosted Hamas’ position. This is not the Middle East of the last war, in 2008-09, when, for the most part, the Arab world stood by as Israel subjected Gaza to overwhelming and disproportionate bombing. That conflict killed 1,387 Palestinians and 13 Israelis. Hosni Mubarak’s government in Cairo even assisted the Israeli campaign against Hamas, while the West and Arab world poured money into Fatah’s West Bank government as a counterweight to Hamas. The regional landscape now is entirely different.

Still, despite a warm rhetorical embrace for Hamas, the Egyptian state has yet to significantly change its policy. It hasn’t opened the border with Gaza, nor does it want to do anything that would allow Israel to shift responsibility for Gaza to Egypt. Throughout the cease-fire negotiations, Israel said Egypt would be responsible for keeping the peace. But no matter what Israel says now, the language of the agreement and the reality on the ground make clear that Israel struck a deal with Hamas at Egypt’s insistence, and that Egypt will certainly be no guarantor of Hamas’ behavior. That’s an achievement for the ruling Muslim Brotherhood. As its (and Egypt’s) influence grows, it might be able to promote its preferred exiled Hamas leaders at the expense of the more uncompromising ones in Gaza.

Hamas has other competitors to worry about now. Until the uprisings two years ago, the Middle East’s Islamist movements were mostly on the outside looking in, railing against secular nationalist despots. In fact, Hamas and Hezbollah were the only Islamist movements who could claim to have ascended to power through popular victories at the ballot box. In the pre-uprising Arab world, then, Hamas (like Hezbollah) could plausibly claim some leadership of a regional Islamist movement. No more. The Muslim Brotherhood now governs Egypt. Islamists were elected to power in Tunisia. They have also emerged as power centers in Libya and among the Syrian opposition. Now that Islamists are competing for power in large states, Hamas (and Hezbollah) could shrink to their proper size in terms of influence. This outcome seems even more likely now that Hamas faces a vibrant challenge from jihadi fundamentalists within Gaza who consider Hamas far too moderate.

Hamas has presented itself as a voice for resistance, but as Gaza tries to rebuild and recover from this latest war, the organization will have to grapple with its own authoritarian, corrupt record in power. Its exiled leaders might sound more reasonable to Western ears, but they’re not the ones who actually control territory and manage a government. If it gets what it wants — a central role in Palestinian leadership — Hamas will have to reconcile its own internal factions or else risk a split. On the quickly changing ground of the new Arab politics, Hamas, like other governing movements, will have to articulate an ever-more detailed, constructive program, to convince rather than compel its constituents.

The Crises We’re Ignoring

[Originally published in The Boston Globe.]

During the presidential campaign, two issues often seemed like the only foreign policy topics in the entire world: the Middle East and China. Those are unquestionably important: The wider Middle East contains most of the world’s oil and, currently, much of its conflict; and China is the world’s manufacturing base and America’s primary lender. But there are a host of other issues that are going to demand Washington’s sustained attention over the next four years, and don’t occupy anywhere near the same amount of Americans’ attention.

You could call them the icebergs, largely hidden challenges that lie in wait for the second Obama administration. Like all of us, when it comes to priorities, the people in Washington assume that the thing that comes to mind first must be the most important. The recent crises or tensions with Afghanistan, Benghazi, and China make these feel like the whole story. But in fact they are really just a few chapters, and the ones we’re ignoring completely may actually have the most surprises in store.

If the administration wants to stay ahead of the game, here’s what it will need to spend more of its time and energy dealing with in the coming four years.

Europe’s recovery needs to be managed, and that requires global cooperation and money.

Washington and China, along with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, will have to be closely involved, and that won’t happen without American leadership. Though the European crisis has already been a front-burner problem for two years, in the United States it barely cracks the public agenda except as a rhetorical bludgeon: “That guy wants to turn America into Greece!” But Europe’s importance to the global economy, and to America, is staggering: It’s the world’s largest economic bloc, worth $17 trillion, and it’s the US’s largest trading partner. If Europe goes down, we all go down.

Climate change. No politician likes to talk about climate change. It’s depressing news. It’s become highly partisan in this country, and it has no obvious solution even for those who understand the threat. It requires discussion of all kinds of hugely complex, dull-sounding science. When we do talk about it as a political issue, it’s largely as a domestic one: saving energy, dealing with the increasing fury and frequency of storms like Hurricane Sandy, investing in new infrastructure.

In fact, climate change is a massive foreign policy issue as well. On the preventive side, any emissions reduction requires cooperation across borders—between small numbers of powerful nations, like America and China, along with massive worldwide accords like the failed Kyoto Protocol. The responses will often need to be global as well. Rising oceans and temperatures have no regard for national boundaries, and most of the world’s population lives near soon-to-be-vulnerable coastlines. Entire cities might have to move, or be rebuilt, often across

borders. Sandy could cost the American Northeast close to $100 billion when all is said and done (current damage estimates already top $50

billion). Imagine the price of climate-proofing the cities where most of the world lives—Mumbai, Shangahi, Lagos, Alexandria, and so on. Climate change, if unaddressed, could well become an American security issue, propelling unrest and failed states that will spur threats against the US.

Pakistan. Like our tendency to obsess over shark attacks rather than, say, the more significant risk of getting hit by a car, we often find our foreign policy elite preoccupied with rare, dramatic potential threats rather than actual banal ones. You’ll keep hearing about Iran, which might one day have a bomb and which emits noxious rhetoric while supporting well-documented militant groups like Hezbollah. What we really need to hear more and do more about, however, is a regional power that already has nukes (90 to 120 warheads), that is reportedly planning for battlefield bombs that are easier to misplace or steal, and that sponsors rogue terrorist groups that have been regularly killing people in Afghanistan and India for years.

That country is Pakistan. Power there is split among an unstable cast of characters: a dictatorial military, super-empowered Islamic fundamentalists, and a corrupt civilian elite. A significant portion of its huge population has been radicalized, and can easily flit across borders with Iran, Afghanistan, and India. Pakistan isn’t a potential problem; it’s a huge actual problem, a driver of war in Afghanistan, a sponsor of killers of Americans, and perennially, the only actor in the world that actively poses the threat of nuclear war. (The hot war between India and Pakistan in Kargil in 1999 was the first active conflict between two nuclear powers. It’s not talked about much, but remains a genuine nightmare scenario.) Pakistan is also a huge recipient of American aid. We need to find leverage and work to contain, restrain, and stabilize Pakistan.

Transnational crime and drugs. When it comes to violence in the world, foreign-policy thinkers tend to think first about wars, militaries, and diplomacy. But to save money and lives, it would be smarter to think about drugs. In much of the world, the resources spent and lives lost to criminal syndicates in the drug war rival the costs of traditional conflict. Narco-states in the Andes and, increasingly, Central America, make life miserable for their own inhabitants. Criminal off-the-book profits symbiotically feed international crime and terrorism. And in every region of the world, drugs provide the economic engine and financing for militias and terrorist groups; they fuel innumerable security problems, such as human trafficking, illicit weapons sales, piracy, and smuggling. Ultimately, wherever the drug business flourishes, it tends to corrode state authority, leaving vast ungoverned swaths of territory and promoting political violence and weak policing.

The United States pays a lot of attention to this problem in Afghanistan and Mexico, but it’s a drain on resources in corners of the globe that get less attention, from Southeast Asia to Africa. Washington needs to approach the international illegal drug trade like the globalized, multifaceted problem that it is, requiring international law enforcement cooperation but also smart economic solutions to change the market, including legalization.

Mexico. It feels almost painfully obvious, but it’s been a long time since a US president has prioritized our next-door neighbor. Our economies are inextricably linked. America’s supposed problem with illegal immigration is actually the organic

development of a fluid shared labor market across the US-Mexico border. Meanwhile, the distant war in Afghanistan eats up an enormous amount of resources while another conflict races on next door: Mexico’s increasingly violent drug war. Since 2006, it has claimed 50,000 lives, and the violence regularly spills over the border. Washington has collaborated piecemeal with Mexico’s government, but this is a regional conflict, involving criminal syndicates indifferent to jurisdiction. The United States needs to persuade Mexico to pursue a less violent, more sustainable strategy to counter the drug gangs, and then partner with the government there wholeheartedly.

The dangerous Internet. Cyber security might sound like a boondoogle for defense contractors looking for more money to spend on a ginned-up threat. Yet in the last year we’ve seen the real-world consequences of cyber attacks on Iran’s nuclear program, apparently orchestrated by the

United States and Israel, and an effective cyber response apparently by Iran that hobbled Saudi Arabia’s oil industry. Harvard’s Joseph Nye points out that cyber espionage and crime already pose serious transnational threats, and recent developments show how war and terrorism will spill into our online networks, potentially threatening everything from our power supply to our personal data.

The US budget. Elementary economics usually begins with the discussion of guns vs. butter: You can’t pay for everything given limited resources, so do you eat or defend yourself? For generations, America has had the luxury of not really having to choose: The economy has mostly boomed since

World War II, meaning we never had to cut anything fundamentally important. But America now faces a contracting global economy and a world in which it increasingly has to share resources with other rising powers. This is unfamiliar, and unhappy, territory: America’s next defense and foreign affairs budgets will probably be the first since the Second World War to require serious downsizing at a time when there are actual credible threats to the United States.

The Americans who reelected President Obama didn’t care that much about his foreign policy, according to polls. And, perhaps fittingly, Obama dealt with the rest of world during his first term with competence and caution rather than with flair and executive drive. His impressive focus on Al Qaeda hasn’t been mirrored so far in the rest of his national security policy, made by a team better known for its meetings than for setting clear priorities.

In the wake of a decisive reelection, Obama will have the political latitude to shape a more creative and forward-thinking foreign policy in his second term. If he does, he’ll have to work around both deeply divided legislators and a constrained budget: We simply can’t pay for everything, from land wars to cyber threats to sea walls to protected American industries. The priorities the next administration chooses—and its ability to pass any budget—will dramatically shape the kind of foreign influence America yields over the next four years.

The Carter Doctrine: A Middle East strategy past its prime

[From The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

Cops say they figure out a suspect’s intentions by watching his hands, not by listening to what comes out of his mouth. The same goes for American foreign policy. Whatever Washington may be saying about its global priorities, America’s hands tend to be occupied in the Middle East, site of all America’s major wars since Vietnam and the target of most of its foreign aid and diplomatic energy.

How to handle the Middle East has become a major point in the presidential campaign, with President Obama arguing for flexibility, patience, and a long menu of options, and challenger Mitt Romney promising a tougher, more consistent approach backed by open-ended military force.

Lurking behind the debate over tactics and approach, however, is a challenge rarely mentioned. The broad strategy that underlies American policy in the region, the Carter Doctrine, is now more than 30 years old, and in dire need of an overhaul. Issued in 1980 and expanded by presidents from both parties, the Carter doctrine now drives American engagement in a Middle East that looks far different from the region for which it was invented.

President Jimmy Carter confronted another time of great turmoil in the region. The US-supported Shah had fallen in Iran, the Soviets had invaded Afghanistan, and anti-Americanism was flaring, with US embassies attacked and burned. His new doctrine declared a fundamental shift. Because of the importance of oil, security in the Persian Gulf would henceforth be considered a fundamental American interest. The United States committed itself to using any means, including military force, to prevent other powers from establishing hegemony over the Gulf. In the same way that the Truman Doctrine and NATO bound America’s security to Europe’s after World War II, the Carter Doctrine elevated a crowded and contested Middle Eastern shipping lane to nearly the same status as American territory.

In 2012, we look back on a recent level of American engagement with the Middle East never seen before. Even the failures have been failures from which we can learn. The decade that began with the US invasion of Afghanistan and ended with a civil war in Syria holds some transformative lessons, ones that could point the next president toward a new strategy far better suited to what the modern Middle East actually looks like—and to America’s own values.

***

President Carterissued his new doctrine in what would turn out to be his final State of the Union speech in January 1980. America had been shaken by the oil shocks of the 1970s, in which the Arab-dominated OPEC asserted its control, and also by the fall of the tyrannical Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran, who had been a stalwart security partner to the United States and Israel.

Nearly everyone in America and most Western economies shared Carter’s immediate goal of protecting the free flow of oil. What was significant was the path he chose to accomplish it. Carter asserted that the United States would take direct charge of security in this turbulent part of the world, rather than take the more indirect, diplomatic approach of balancing regional powers against each other and intervening through proxies and allies. It was the doctrine of a micromanager looking to prevent the next crisis.

Carter’s focus on oil unquestionably made sense, and the doctrine proved effective in the short term. Despite more war and instability in the Middle East, America was insulated from oil shocks and able to begin a long period of economic growth, in part predicated on cheap petrochemicals. But in declaring the Gulf region an American priority, it effectively tied us to a single patch of real estate, a shallow waterway the same size as Oregon, even when it was tangential, or at times inimical, to our greater goal of energy security. The result has been an ever-increasing American investment in the security architecture of the Persian Gulf, from putting US flags on foreign tankers during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, to assembling a huge network of bases after Operation Desert Storm in 1991, to the outright regime-building effort of the Iraq War.

In theory, however, none of this is necessary. America doesn’t really need to worry about who controls the Gulf, so long as there’s no threat to the oil supply. What it does need is to maintain relations in the region that are friendly, or friendly enough, and able to survive democratic changes in regime—and to prevent any other power from monopolizing the region.

The Carter Doctrine, and the policies that have grown up to enforce it, are based on a set of assumptions about American power that might never have been wholly accurate. They assume America has relatively little persuasive influence in the region, but a great deal of effective police power: the ability to control major events like regional wars by supporting one side or even intervening directly, and to prevent or trigger regime change.

Our more recent experience in the Middle East has taught us the opposite lesson. It has become painfully clear over the last 10 years that America has little ability to control transformative events or to order governments around. Over the past decade, when America has made demands, governments have resolutely not listened. Israel kept building settlements. Saudi Arabia kept funding jihadis and religious extremists. Despots in Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, and Libya resisted any meaningful reform. Even in Iraq, where America physically toppled one regime and installed another, a costly occupation wasn’t enough to create the Iraqi government that Washington wanted. The long-term outcome was frustratingly beyond America’s control.

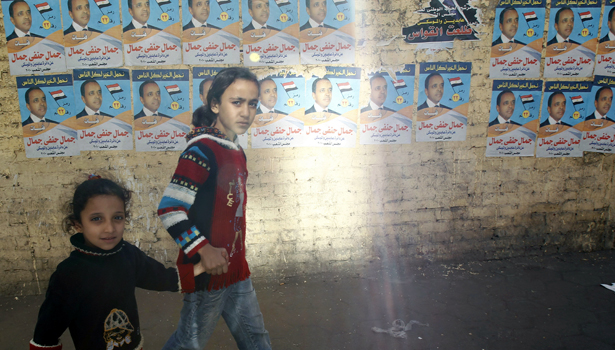

When it comes to requests, however, especially those linked to enticements, the recent past has more encouraging lessons. Analysts often focus on the failings of George W. Bush’s “freedom agenda” period in the Middle East; democracy didn’t break out, but the evidence shows that no matter how reluctantly, regional leaders felt compelled to respond to sustained diplomatic requests, in public and private, to open up political systems. It wasn’t just the threat of a big stick: Egypt and Israel weren’t afraid of an Iraq-style American invasion, yet they acceded to diplomatic pressure from the secretary of state to liberalize their political spheres. Egypt loosened its control over the opposition in 2005 and 2006 votes, while Israel let Hamas run in (and win) the 2006 Palestinian Authority elections. Even prickly Gulf potentates gave dollops of power to elected parliaments. It wasn’t all that America asked, but it was significant.

Paradoxically, by treating the Persian Gulf as an extension of American territory, Washington has reduced itself from global superpower to another neighborhood power, one than can be ignored, or rebuffed, or hectored from across the border. The more we are committed to the Carter Doctrine approach, which makes the military our central tool and physical control of the Gulf waters our top priority, the less we are able to shape events.

The past decade, meanwhile, suggests that soft power affords us some potent levers. The first is money. None of the Middle Eastern countries have sustainable economies; most don’t even have functional ones. The oil states are cash-rich but by no means self-sufficient. They’re dependent on outside expertise to make their countries work, and on foreign markets to sell their oil. Even Israel, which has a real and diverse economy, depends on America’s largesse to undergird its military. That economic power gives America lots of cards to play.

The second is defense. The majority of the Arab world, plus Israel, depends on the American military to provide security. In some cases the protection is literal, as in Bahrain, Qatar, and Kuwait, where US installations project power; elsewhere, as in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan, it’s indirect but crucial. (American contractors, for instance, maintain Saudi Arabia’s air force.) America’s military commitments in the Middle East aren’t something it can take or leave as it suits; it’s a marriage, not a dalliance. A savvier diplomatic approach would remind beneficiaries that they can’t take it for granted, and that they need to respond to the nation that provides it.

***

The Carter Doctrineclearly hasn’t worked out as intended; America is more entangled than ever before, while its stated aims—a secure and stable Persian Gulf, free from any outside control but our own—seem increasingly out of reach. A growing, bipartisan tide of policy intellectuals has grappled with the question of what should replace it, especially given our recent experience.

One response has been to seek a more morally consistent strategy, one that seeks to encourage a better-governed Middle East. This idea has percolated on the left and the right. Alumni of Bush’s neoconservative foreign-policy brain trust, including Elliott Abrams, have argued that a consistent pro-democratic agenda would better serve US interests, creating a more stable region that is less prone to disruptions in the oil supply. Voices on the left have made a similar argument since the Arab uprisings; they include humanitarian interventionists like Anne-Marie Slaughter at Princeton, who argue for stronger American intervention in support of Syria’s rebels. Liberal fans of development and political freedoms have called for a “prosperity agenda,” arguing that societies with civil liberties and equitably distributed economic growth are not only better for their own citizens but make better American allies.

Then there’s a school that says the failures of the last decade prove that America should keep out of the Middle East almost entirely. Things turn out just as badly when we intervene, these critics argue, and it costs us more; oil will reach markets no matter how messy the region gets. This school includes small-footprint realists like Stephen Walt at Harvard and pugilistic anti-imperial conservatives like Andrew Bacevich at Boston University. (Bacevich argues that the more the US intervenes with military power to create stability in the oil-producing Middle East, the more instability it produces.)

While the realists think we should disentangle from the region because the US can exert strategic power from afar, others say we should pull back for moral reasons as well. That’s the argument made over the last year by Toby Craig Jones, a political scientist at Rutgers University who says that the US Navy should dissolve its Fifth Fleet base so it can cut ties with the troublesome and oppressive regime in Bahrain. America’s military might guarantees that no power—not Iran, not Iraq, not the Russians—can sweep in and take control of the world’s oil supply. Therefore, the argument goes, there’s no need for America to attend to every turn of the screw in the region.

What’s clear, from any of these perspectives, is that the Carter Doctrine is a blunt tool from a different time. It’s now possible, even preferable, to craft a policy more in keeping with the modern Middle East, and also more in line with American values. It might sound obvious to say that Washington should be pushing for a liberalized, economically self-sufficient, stable, but democratic Middle East, and that there are better tools than military power to reach those aims. In fact, that would mark a radical change for the nation—and it’s a course that the next president may well find within his power to plot.

How the Arab Uprisings Left Hezbollah Behind

[Published in The New Republic.]

Hassan Nasrallah has always been more sophisticated than the caricatured nightmare featured in the breathless propaganda of Hezbollah’s many enemies. Even at his most noxious he usually managed to present himself as a man of principle. That’s why it was almost sad to see Nasrallah this week pandering like an old-time Arab despot to public anger over the misbegotten Prophet Mohammed YouTube clip.

“America, which uses the pretext of freedom of expression needs to understand that putting out the whole film will have very grave consequences around the world,” Nasrallah said at a Hezbollah rally on September 17, one of the exceedingly rare occasions on which he appeared in public since he went into hiding during the 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon. “The world should know our anger will not be a passing outburst but the start of a serious movement that will continue on the level of the Muslim nation to defend the Prophet of God.” Though the message sounds militant, it was actually just a flailing attempt to catch up to developments elsewhere in the region. Hezbollah, which used to set the Arab world’s trends, now finds itself forced to opportunistically jump on the latest global Islamist bandwagon.

In fact, Hezbollah’s embrace of the controversy over the video marks a final stage of its speedy evolution from revolutionary militant resistance movement to Machiavellian establishment power center. Lebanon’s Party of God once literally threw bombs at those who stood in the way of its ideology, attacking powerful enemies like America and Israel as well as smaller rivals at home. Today, Hezbollah represents the very sort of power it used to oppose. It dominates Lebanese politics as the majority party, choosing the prime minister; it commands a formidable standing army; its complicity in domestic political assassinations no longer is credibly debated; and it remains comfortable with its deep, compromised embrace of Bashar Al-Assad’s criminal regime in Syria.

There’s no mystery here: Hezbollah has become essentially conservative, fearful of the status of its political interests and financial and military networks. The very fact that Nasrallah felt compelled to risk emerging from his underground safe haven suggests that he fears very seriously for his organization’s future. It’s a remarkable change for a movement that was once confident in its ideological rigor and in its ability to earn unparalleled popular support in the region.

IN THE FIRST two decades of Nasrallah’s stewardship, Lebanon’s Party of God transformed itself from a potent but small militant group, best known for spectacular terrorist attacks, into the driver of the Axis of Resistance, crafting a widely appealing message of nationalism and fearless self-reliance built on an uncompromising opposition to Israel and the United States. Just two years ago, Nasrallah was still crowing about an open war with Israel and was still reaping the political benefit of being seen as the sole Arab leader to stand up to the U.S. and Israel.

Today, of course, his critical patron in Syria is teetering, threatening to vastly curtail Hezbollah’s military power, and his source of money and weapons in Iran is distracted by sanctions, a feeble economy and its nuclear showdown with the West. More importantly, the Arab world is awash in genuine retail politics. Indeed, what ultimately broke Hezbollah’s monopoly on popular legitimacy—what ultimately put the Axis of Resistance to rest as a meaningful political or ideological bloc in the Middle East—were the Arab revolts.

Like any establishment power with too much to lose, Hezbollah has kept a distance from uprisings that empower competitors. Still, there is no denying that those rivals have risen throughout the region; fire-breathers and populists have taken position all along the political spectrum from the Islamist right to the secular-anarchist left.

In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood embraces many similar views to Hezbollah, without the call to violence and regional war. There are Salafi extremists running political parties, and there are secular nationalists who sound every bit as uncompromising as Hezbollah when it comes to Israel. To round out the picture, there are voices that oppose violence and endorse diplomacy and pluralistic electoral politics, again along all parts of the spectrum (although sadly, they form a minority). Even Hamas, one of the four pillars of the Axis, has quietly quit its alliance with Syria (and its reliance on Iranian money), gambling that a dignified and principled stand against Bashar Al-Assad will pay handsome long-term dividends in popularity and legitimacy.

Hezbollah, however, calculated that it had no such option. The Assad regime has long allowed Syria to serve as Hezbollah’s rear staging area. Weapons transit through the Damascus airport to Hezbollah training camps and depots. In times of war, trucks can ferry all manner of material into Lebanon from safe havens in Syria. Without Syria, Hezbollah could find itself isolated in the tiny confines of Lebanon, where about half the population detests Hezbollah and its project. For now, Hezbollah’s hard power is undiminished, but the future doesn’t look so secure for the Party of God.

And so, backed into a corner, Hezbollah has responded to the radical transformation of Arab politics much like American policy makers, improvising on an ad hoc basis. Hezbollah has doubled down on its anti-Israel and anti-American credentials, but has abandoned the more inclusive nationalistic part of its resistance credo that arguably propelled its meteoric rise and sustained power. Nasrallah used to unabashedly endorse any populist Arab movement that opposed dictatorship at home or Western ambitions abroad. Now, Hezbollah seems to pick and choose the occasions when justice matters: Yes for the Shia of Bahrain, less so for the citizens of Egypt, and not so much for the Sunnis of Syria. When Israel was occupying southern Lebanon or bombing its villages, and U.S.-backed tyrants were oppressing much of the region, the sense of a powerful, monolithic enemy united support behind Hezbollah. The new reality is patently more complex, with none of the old bugbears solely to blame for the Arab world’s woes. Without a villain, Hezbollah’s fundamental recipe for power and legitimacy loses its yeast.

Of course, Hezbollah has never become explicitly or exclusively sectarian. It has managed to maintain a tight, six-year alliance with Lebanon’s largest Christian party, Michael Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement. But this has never been an especially durable strategy. The contradictions are profound and irreconcilable. To some, Hezbollah is a pan-Arab guerilla front against Israel. To some it is a dogmatic Shia religious movement that sincerely embraces Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s theocratic theology. And to some, it is a shrewd and pragmatic political actor that knows how to make the trains run on time. Yet, it cannot be all of these things at once.

Hezbollah has never been free of such tensions and Nasrallah has always managed to masterfully hold the movement together despite them. As the disconnect has grown wider, however, the false narrative that Hezbollah uses to bridge the gap has grown ever more tenuous. It’s getting harder for even Hezbollah’s most committed supported to believe that Syria’s uprising is a foreign, American-backed plot to massacre innocents, create sectarian strife, and impose Israeli hegemony over the Levant. As the civil war next door spills ever more toxically across the border into Lebanon, claiming lives in Hezbollah’s neighborhoods, it has become impossible to maintain the charade of denial. As the nature of the Syrian regime’s brutality (and the cynicism with which Nasrallah has blessed it) begins to sink in, Hezbollah risks ending up looking more and more like a Shia sectarian movement, just another player in a polarized regional struggle.

If history is any guide, of course, Hezbollah will be nimble and adaptive, and use any circumstances possible to turn a bleak outlook to its advantage. Some holes, however, are too deep to climb out of. The fall of the House of Assad might be one of them. And, judging from his flailing, Nasrallah himself seems to know it.

Not an Ally, Not an Enemy

President Obama struck a powerful chord last night when asked about Egypt’s tepid response to the incursion on the American Embassy in Cairo. “I don’t think that we would consider them an ally, but we don’t consider them an enemy,” Obama told Telemundo. The American president’s pointed observation balanced the need to put Egypt on notice against the importance, in diplomacy, of not sounding like a scold.

In this case, Egypt’s president Mohamed Morsi has behaved like a recalcitrant populist, trying to benefit domestically from anger over a private American film that insulted Islam, while not losing any of America’s vital support for Egypt. Perhaps Morsi has read recent Egyptian history and concluded that Cairo’s support is so important that Washington will bear any humiliation in order to retain the special military and security relationship. Yet all international relations have their limits; and Morsi might have forgotten that America accepted a great amount of bad behavior by the SCAF during the 18-month transitional period that followed Mubarak’s fall — but now we’re dealing with an elected sovereign government with a popular mandate and popular accountability. This is the real thing, a democratically governed Egypt. Its president is now responsible for his behavior and for his country’s policy.

In a chat yesterday on Capital New York, I said that Obama would need to pointedly express America’s anger toward Egypt.

Don’t get me wrong: he needs to “engage” the Brotherhood, which means, “have relations” with it. In this case, the engagement should consist of a cold, angry, demand: that they immediately condemn the invasion of the embassy grounds, and that they act responsibly to cool anti-American sentiment—if they expect our financial aid, our military aid, and our indispensable support in getting the IMF and other international assistance vital to Egypt’s economic survival. … I think it will hurt Obama if he doesn’t criticize Egypt aggressively, and in public. And I think the damage could grow if people connect these breaches to America’s broader directionless in the wake of the Arab uprisings.

That’s the real problem, by the way—not the stuff Romney is bringing up.

Obama might finally be making some progress, a year and a half late, in coining a coherent response to the Arab uprisings. His comments about Egypt suggest that Washington is mature and wise enough to begin navigating that gray area between subservient client state and outright enemy; most of the post-uprising Arab world will fall somewhere in that confusing terrain that houses most sovereign states, neither “with us” nor “against us.”

America is contemplating an Egypt that won’t march in lockstep with all its interests. Egypt doesn’t want to go to war with Israel for its own reasons, but it’s likely to be much more hostile and less cooperative there. Same on defense and counter-terrorism. Cairo and Washington will have to negotiate their limited shared interests. The flip side, however, might not yet have dawned on Egypt’s new leaders; America is under no obligation to underwrite Egypt’s military and to a lesser degree is economy with no-strings-attached billions. An independent Egyptian government (or depending on your perspective, an irritating one) will surely be a boon to Egypt’s sense of honor, pride, and autonomy. But it won’t come without consequences. Angering an American government, even a patient one, still carries costs.

A World of Messy Borders? Get Used to It

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

Morsi: Dictator, Rebalancer, or Both?

A very interesting conversation on Warren Olney’s To the Point over the implications of Morsi trying to take control. On the one hand, he actually has a mandate, public support, and a known ideology. On the other hand, the Muslim Brotherhood and now Morsi, during the transition, have time and again made self-serving power grabs and exhibited a propensity for authoritarianism. Listen here for a sometimes sharp debate involving me, Marc Lynch, Ehud Yaari, and Kareem Fahim.

Everybody’s an Islamist Now

The case that a political term has outlived its usefulness

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

To watch the Arab world’s political transformation over the past year has been, in part, to track the inexorable rise of Islamism. Islamist groups—that is, parties favoring a more religious society—are dominating elections. Secular politicians and thinkers in the Arab world complain about the “Islamicization” of public life; scholars study the sociology of Islamist movements, while theologians pick apart the ideological dimensions of Islamism. This March, the US Institute for Peace published a collection of essays surveying the recent changes in the Arab world, entitled “The Islamists Are Coming: Who They Really Are.”

From all this, you might assume that “Islamism” is the most important term to understand in world politics right now. In fact, the Islamist ascendancy is making it increasingly meaningless.

In Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, the most important factions are led overwhelmingly by religious politicians—all of them “Islamist” in the conventional sense, and many in sharp disagreement with one another over the most basic practical questions of how to govern. Explicitly secular groups are an exception, and where they have any traction at all they represent a fragmented minority. As electoral democracy makes its impact felt on the Arab world for the first time in history, it is becoming clear that it is the Islamist parties that are charting the future course of the Arab world.

As they do, “Islamist” is quickly becoming a term as broadly applicable—and as useless—as “Judeo-Christian” in American and European politics. If important distinctions are emerging within Islamism, that suggests that the lifespan of “Islamist” as a useful term is almost at an end—that we’ve reached the moment when it’s time to craft a new language to talk about Arab politics, one that looks beyond “Islamist” to the meaningful differences among groups that would once have been lumped together under that banner.

Some thinkers already are looking for new terms that offer a more sophisticated way to talk about the changes set in motion by the Arab Spring. At stake is more than a label; it’s a better understanding of the political order emerging not just in the Middle East, but around the world.

THE TERM “ISLAMIST” came into common use in the 1980s to describe all those forces pushing societies in the Islamic world to be more religious. It was deployed by outsiders (and often by political rivals) to describe the revival of faith that flowered after the Arab world’s defeat in the 1967 war with Israel and subsequent reflective inward turn. Islamist preachers called for a renewal of piety and religious study; Islamist social service groups filled the gaps left by inept governments, organizing health care, education, and food rations for the poor. In the political realm, “Islamist” applied to both Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, which disavowed violence in its pursuit of a wealthier and more powerful Islamic middle class, and radical underground cells that were precursors to Al Qaeda.

What they had in common was that they saw a more religious leadership, and more explicitly Islamic society, as the antidote to the oppressive rule of secular strongmen such as Hafez al-Assad, Hosni Mubarak, and Saddam Hussein.

Over the years, the term “Islamist” continued to be a useful catchall to describe the range of groups that embraced religion as a source of political authority. So long as the Islamist camp was out of power, the one-size-fits-all nature of the term seemed of secondary importance.

But in today’s ferment, such a broad term is no longer so useful. Elections have shown that broad electoral majorities support Islamism in one flavor or another. The most critical matters in the Arab world—such as the design of new constitutional orders in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya—are now being hashed out among groups with competing interpretations of political Islam. In Egypt, the non-Islamic political forces are so shy about their desire to separate mosque from government that many eschew the term “secular,” requesting instead a “civil” state.

In Tunisia’s elections last fall, the Islamist Ennahda Party—an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood—swept to victory, but is having trouble dealing with its more doctrinaire Islamist allies to the right. In Libya, virtually every politician is a socially conservative Muslim. The country’s recent elections were won by a party whose leaders believe in Islamic law as a main reference point for legislation and support polygamy as prescribed by Islamic sharia law, but who also believe in a secular state—unlike their more Islamist rivals, who would like a direct application of sharia in drafting a new constitutional framework.

In Egypt, the two best-organized political groups since the fall of Mubarak have been the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi Noor Party—both “Islamist” in the broad sense, but dramatically different in nearly all practical respects. The Brotherhood has been around for 84 years, with a bourgeois leadership that supports liberal economics and preaches a gospel of success and education. The rival Salafi Noor Party, on the other hand, includes leaders who support a Saudi-style extremist view of Islam that holds the religious should live as much as possible in a pre-modern lifestyle, and that non-Muslims should live under a special Islamic dispensation for minorities. A third Islamist wing in Egypt includes the jihadists—the organization that assassinated President Anwar Sadat in 1981, which has officially renounced violence and has surfaced as a political party. (Its main agenda item is to advocate the release of “the blind sheikh,” Omar Abdel-Rahman imprisoned in the United States as the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.)

“ISLAMIST” MIGHT BE an accurate label for all these parties, but as a way to understand the real distinctions among them it’s becoming more a hindrance than a help. A useful new terminology will need to capture the fracture lines and substantive differences among Islamic ideologies.

In Egypt, for example, both the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis believe in the ultimate goal of a perfect society with full implementation of Islamic sharia. Yet most Brothers say that’s an abstract and unattainable aim, and in practice are willing to ignore many provisions of Islamic law—like those that would limit modern finance, or those that would outright ban alcohol—in the interest of prosperity and societal peace. The Salafis, by contrast, would shut down Egypt’s liquor industry and mixed-gender beaches, regardless of the consequences for tourism or the country’s Christian minority.

There’s a cleavage between Islamists who still believe in a secular definition of citizenship that doesn’t distinguish between Muslims and non-Muslims, and those who believe that citizenship should be defined by Islamic law, which in effect privileges Muslims. (Under Saudi Arabia’s strict brand of Islamist government, the practice of Christianity and Shiite Islam is actually illegal.) And there’s the matter of who would interpret religious law: Is it a personal matter, with each Muslim free to choose which cleric’s rulings to follow? Or should citizens be legally required to defer to doctrinaire Salafi clerics?

Many thinkers are trying to craft a new language for the emerging distinctions within Islamism. Issandr El Amrani, who edits The Arabist blog and has just started a new column for the news site Al-Monitor about Islamists in power, suggests we use the names of the organizations themselves to distinguish the competing trends: Ikhwani Islamists for the establishment Muslim Brothers and organizations that share its traditions and philosophy; Salafi Islamists for Salafis, whose name means “the predecessors” and refers to following in the path of the Prophet Mohammed’s original companions; and Wasati Islamists for the pluralistic democrats that broke away from the Brotherhood to form centrist parties in Egypt.