One-Man Tent, Tahrir version

How to keep cool in the middle of a day-long protest in a shadeless square with the sun pushing temperatures to 100 degree Fahrenheit? Here was one man’s resourceful solution on July 8.

Reinvigorating Egypt’s Revolution

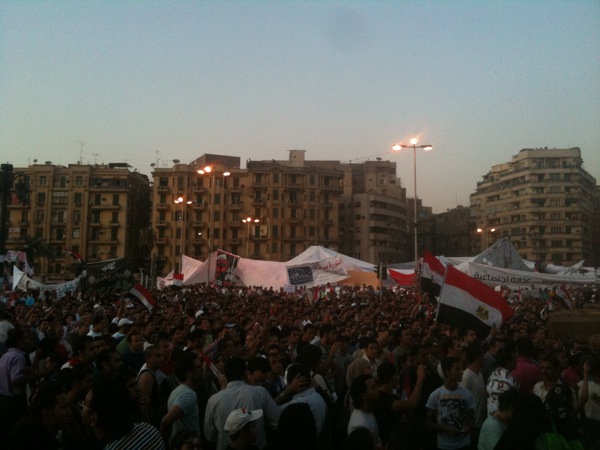

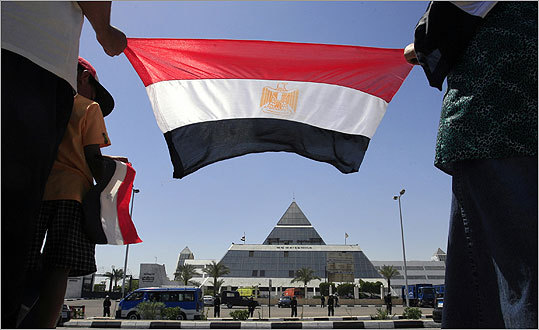

CAIRO, Egypt — Friday’s “Day of Determination” (or “Day of Persistence”) continued overnight and into Saturday as a sit-in in Tahrir Square. It was the largest since President Hosni Mubarak stepped down, and it marked a sort of inflection point for the popular uprising that began on January 25.

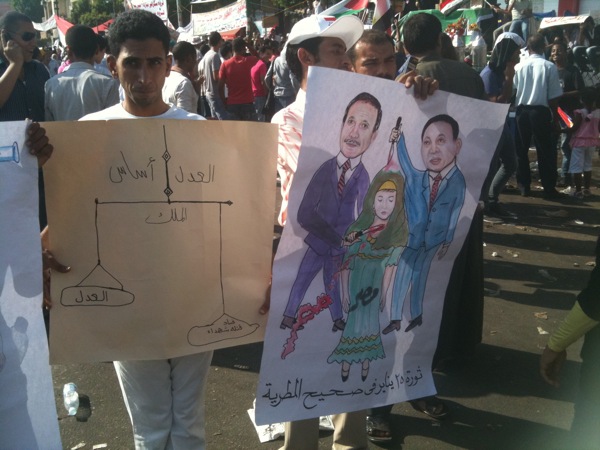

For the first time since mid-February, the crowd filled the entire square, and drew scores of regular folk who wouldn’t normally define themselves as political activists. The demonstration swelled to revolutionary size, to a large extent, because its organizers consciously eschewed politics. Instead they resorted to a lowest-common denominator appeal to prosecute Hosni Mubarak and his henchmen. Justice for the crimes of the past, and for the crimes that continue, including police brutality, unaccountable government, and military detentions of protesters. Two words echoed above all: justice, and revenge.

That simple call galvanized the protest, although to some was its Achilles heel.

“The blood of the martyrs won’t be wasted,” the crowds chanted. Protesters carried pictures of Hosni Mubarak hanging from a noose (a common motif, also stenciled on walls around Tahrir).

A performer named Waleed Sheikh held a Mubarak marionette wearing the traditional red Egyptian death row suit, a star of David on the front. “I am manipulating him like he used to manipulate us!” Waleed said as he made the Mubarak doll dance, to the wild applause of onlookers.

Many of those in crowd said they hadn’t joined a protest since February, but were galvanized by the ruling junta’s foot-dragging on trials for Mubarak cronies and on police reform.

“I thought the government would be purified after the revolution,” said chemist Mahmoud Fathy, 29. “They are trying to outsmart the revolution, to outwait us and change nothing.”

Day of Persistence on The World

Marco Werman asks me about today’s protests in Tahrir on The World. I’ll post more about this later, but the crowd today was larger and more harmonious than at any point since February, when President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. It certainly marked some kind of turning point in terms of popular impatience with the general who run Egypt, and it might signal something important about the enduring appeal of revolution and the failure, so far, of opposition politics to capture Egypt’s imagination.

Pushing the Boundaries

CAIRO, Egypt — On the fourth day of publication, Ibrahim Eissa bounds into the newsroom of Tahrirnewspaper, his latest anti-establishment venture and quite literally the offspring of Egypt’s January uprising. It’s midday, and he’s ready to plough through the day’s diet of news stories, opinion columns, and satirical cartoons that seem poised to make this tabloid the paper of record for the demographic known here simply as “the youth of the revolution.”

He’s wearing his trademark brown suspenders, and his trapezoidal mustache twitches as he hails the receptionist, the foreign news editor, and the managing editor.

“I’m the oldest person here,” proclaims Eissa, who appears also to be the most energetic. He later explains that youthfulness is a point of pride in Egypt’s gerontocracy, where the octogenarian president appointed septuagenarian deputies to run his police state. Field Marshal Mohammed Tantawi, Egypt’s current leader, is 75.

Tahrir launched at the beginning of July after months of planning. The paper is determined to challenge authoritarianism and corruption, and to cross whatever red lines Egypt’s rulers try to draw around a free press.

“Before, Mubarak was the red line,” Eissa says as he discusses the paper in his narrow corner office, as editors parade through. “Now the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces has replaced Mubarak. They don’t want anyone to criticize them directly.”

Eissa still tends the most boisterous patch of Egypt’s still-tender garden of free expression. At 45, the veteran editor might boast the toughest hide of any Egyptian journalist. During the long tenure of President Hosni Mubarak, Eissa was fired from nearly a dozen jobs and dashed all the regime’s taboos. In 2007, he was sentenced to a year in prison for writing about Mubarak’s failing health, which was treated as a state secret. (The sentence later was overturned on appeal, but the case successfully muzzled the Egyptian press.) For five years, he ran the liveliest paper in Egypt, Al Dostour (“The Constitution”), building it into enough of a threat that in October 2010 Mubarak had a crony buy the paper and fire Eissa the next day.

Read the rest in The Atlantic.

Hezbollah Is In Trouble

During the six turbulent years since Rafik Hariri was blown up on the Beirut waterfront, supporters of the outspoken billionaire former prime minister longed for the day that his killers would face justice.

But the indictments submitted this week by the UN-mandated Special Tribunal for Lebanon hit with more splutter than splash. In the short term, Hezbollah will face minimal fallout from the charges against two of its officials, which the Tribunal named as ringleaders in the assassination.

The more serious threats to Hezbollah’s primacy in the long run lie elsewhere. The first comes from the Tribunal, which will exert leverage over Lebanon not by the suspects it indicts but by the strength of the case it presents. The second and perhaps more important challenge to Hezbollah stems from the radical political changes sweeping the Arab world, which threaten its Syrian government sponsors in Damascus, and have put Hezbollah in the position of siding with authoritarian dictators in the era of the Arab spring.

Read the rest in The Atlantic.

Back in Tahrir for Tear Gas and Detention

I returned to Egypt on Tuesday, escaping the tear gas and riots in Athens for the Cairene edition. I followed the parallel clashes on Twitter, and then headed out to Tahrir. The scene felt different than in February — a somewhat hard to parse mix of earnest protesters, activists, disenfranchised Egyptians, thugs, and soccer hooligans. As I tried to interview the father of a martyr from January, a pair of middle-aged men confronted me, with a mix of bullying, menace and manhandling that I’ve come to associate with regime figures or their henchmen. “How do we know you’re not a Jew?” one of them demanded. He had white hair and wore a light blue suit. With prompting from the crowd that assembled he demanded my Egyptian press card, which he grabbed, crumpled up, and stuffed in his pocket. After some shoving and shouting, he resolved to present me to the police — obviously, he said, I was a spy and not a journalist. (You can see him in the middle of the group pictured here; I snapped this with my iPhone while the citizens brigade contemplated what to do with me.)

The police officers at Marouf Street were unimpressed. They sent the man and his small mob on their way, and after a short time, the duty officer turned to me. “Imshee,” he said, “leave”* — one of the chants the crowds in Tahrir used to direct at Hosni Mubarak when he still was president.

You can read more detail about the day in my dispatch at The Atlantic.

CAIRO, Egypt — The city is combustible. On Tuesday night, seemingly out of nowhere, fighting engulfed Cairo at a pitch not seen since the Days of Rage in January and February that forced President Hosni Mubarak to resign.

A group of families had gathered in another neighborhood to celebrate the martyrs killed during the revolution; no one knows who organized the event and who attended. No one knows exactly what happened next either — just that police tangled with the families, who then decided to march on the Ministry of the Interior in downtown Cairo. After nightfall, the fighting took on a momentum of its own. Hundreds of demonstrators massed at the interior ministry and later in Tahrir Square. Riot police shot tear gas and, according to protesters, rubber bullets. Demonstrators threw rocks and Molotov cocktails. The fighting surged on throughout the night, unabated.

By noon on Wednesday, several thousands of demonstrators were still battling the riot police. Reinforcements had arrived, including 20 ambulances. The fighting raged on Mohammed Mahmoud, the spur street off the southern end of Tahrir Square leading to the interior ministry. Men on ambulances ferried the hundreds of wounded back to the ambulances. The sting of tear gas stretched half a mile from the clashes, enveloping the entire square. Helpful men offered vinegar and Kleenex to alleviate the pain of inhaling the gas.

I was eager to talk to some of the martyrs’ families, find out how the whole melee began, and see how they felt it would affect their cause. Men and women huddled in knots, ignoring the tear gas, arguing about whether these clashes would undermine the revolution by alienating a wider Egyptian public that is tiring of protests. None of them were relatives of martyrs. Many of them were wary.

“I’ve been in Tahrir since January 25, and a lot of the faces I see out here today are not the usual faces,” said a 27-year-old accountant named Mahmoud. “A lot of them look like thugs.”

*In the original post, I had incorrectly written “emsha” for “imshee.”

End of the Athens Ghetto

A welcome casualty of Greece’s economic meltdown: the most grating exemplar of the cafe-entitlement culture in my neighborhood. Ghetto Luxury Lounge opened around the turn of the millennium, peddling overpriced tequila sunrises and iced cappuccinos to a clientele whose aspirations appeared strangled in their skinny jeans. This weekend I noticed the “For Rent” sign on Ghetto with a jolt of pleasure as sweet and nasty as the drinks it used to serve. Along with all the unwelcome dislocation of the Greek economic crisis, at least we can look forward to a little weeding.

How China Sees the World

My latest column in The Boston Globe:

The specter of a China with rising influence in the world has long provoked anxiety here in America. Like a speeding car that suddenly fills the rearview mirror, China has grown stronger and bolder and has done it quickly: Not only does it hold colossal amounts of American currency and boast a favorable trade deficit, it has increasingly been able to play the heavy with other nations. China is forging commercial relationships with African and Middle Eastern countries that can provide it natural resources, and has the clout to press its prerogatives in more local disputes with its Asian neighbors—including last week’s face-off with Vietnam in the South China Sea.

With China emerging more forcefully onto the world stage, understanding its foreign policy is becoming increasingly important. But what exactly is that policy, and how is it made?

As scholars look deeper into China’s approach to the world around it, what they are finding there is sometimes surprising. Rather than the veiled product of a centralized, disciplined Communist Party machine, Chinese policy is ever more complex and fluid—and shaped by a lively and very polarized internal debate with several competing power centers.

There’s a clear tug of war between hard-liners who favor a nationalist, even chauvinist stance and more globally minded thinkers who want China to tread lightly and integrate more smoothly into international regimes. And the Chinese public might be pushing a China-first mentality more than its leadership. Scholars believe that the boisterous nativism on display in China’s online forums appears to be a major factor pushing Chinese foreign policy in a more hard-line direction.

Today, for all its economic might, China still isn’t considered a global superpower. Its military doesn’t have worldwide reach, and its economy, while prolific, still hasn’t made the transition to producing technology rather than just goods for the world marketplace. Because of its sheer size and the dispatch with which it has moved from Third World economy to industrial powerhouse, however, China’s arrival as a power is considered inevitable.

As it does, understanding its foreign policy becomes only more important. Overall, the contours of its internal policy debates suggest a China that’s more isolated, unsure, and in transition than its often aggressive rhetoric would suggest. The candid discussion underway in China’s own public sphere underscores that China’s positions are still under negotiation. And one thing that emerges is a picture of a powerful state that is refreshingly direct in engaging questions about how to behave in the world as it embarks on what it fully expects will be China’s century.

Discouraging Lessons of History

CAIRO, Egypt — Old ways die hard.

It only requires a quick glance at the new Egyptian junta — as most of the country’s citizens see it — to understand how the military rulers see their inviolable position. On its Facebook page, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces issues terse directives. Egyptian citizens post comments by the tens of the thousands, but there’s never any response. The military’s high-handed public outreach is similarly one-sided. One general appears on television to read the same directives, stony-faced, to a camera. And every now and again, the military stages public “dialogues,” which come across, intentionally or not, as patronizing lectures.

How does the military view its future in Egypt? What internal dynamics are shaping the military’s political strategy, which could in large part determine whether February’s revolution is a success? Within the officer corps, there are diverse views as to how much power the Egyptian army should wield, and how much it should yield to elected civilians.

It can be difficult to get answers to these questions from the military, perhaps in part because they themselves don’t yet know. So I’ve turned to reading history, hoping to find answers there, and was struck once again by the tight congruity between present-day Egypt and the critical points it has experienced over the last century and a half. During much of that time, Egypt has politically lain fallow, either because of self-induced paralysis as during Hosni Mubarak’s rule or long periods of colonial subjugation, as during the era of the British-orchestrated Veiled Protectorate.

Indignant at Syntagma: Tahrir Comes to Athens

Inspired by Egyptians and spurred to action by Spaniards, the Greek people have taken over their capital’s central square to demand, simply, an end to corruption, consumerism, and their nation’s long, self-induced economic immolation. Now that Greece has committed hara-kiri, its citizens can point to other culprits, like bureaucrats from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund who erroneously prescribe austerity at the inflection point of a depression.

Set aside the political economy for a moment, and behold the pop culture of protest. Syntagma Square looks like Tahrir with beer, franks, and port-a-potties. And, oh, not nearly so many people.

Set aside the political economy for a moment, and behold the pop culture of protest. Syntagma Square looks like Tahrir with beer, franks, and port-a-potties. And, oh, not nearly so many people.

Yesterday on an evening tour of the tent city I encountered a drumming circle, some stoners playing the guitar; immigrants rights activists; labor organizers planning the nationwide general strike called for this Tuesday; legions of beer salesmen; a pair of dueling end-of-the-world-is-nigh prophets; a row of sausage salesmen without any customers; representative of NGOs for the homeless, the environment, and other worthy causes; and curious passers-by on their way to the metro entrance.

Supporters rally at the Facebook page “Indignant in Syntagma,” and the rest of Athens plans their days by consulting a student-run page which lists all the strikes that disrupt life in the capital.

Banners declare “The quiet citizen is a useless citizen” and “We are peaceful.” Speechifiers spoke of IMF ineptitude, government failure, and the imperative for labor solidarity on the day of the general strike. “The nation must come to a halt,” a said without any inflection over a megaphone.

Banners declare “The quiet citizen is a useless citizen” and “We are peaceful.” Speechifiers spoke of IMF ineptitude, government failure, and the imperative for labor solidarity on the day of the general strike. “The nation must come to a halt,” a said without any inflection over a megaphone.

The popular grievances are legitimate, of course: the tax scofflaws, union maximalists, over-leveraged materialists, and greedy politicians who ruined the country over the course of 37 years probably include only about half the citizenry. The remainder are justifiably upset that their economic prospects have been doomed as well. Of course, it’s unclear which half is represented in Syntagma Square. But it is clear that they’re peaceful, well-fed, and not likely anytime soon to face a shortage of nicely chilled Mythos Beer.

UPDATE: Today organizers are hoping to bring 1 million people out to the center of Athens. The mass protest is meant to start at 6 p.m., by which time I hope to be sailing away from the mainland, so I’ll have to learn from afar how it goes.

Muslim Brotherhood goes legal

My latest column in The Atlantic considers the turning point reached this week when the Muslim Brotherhood’s political party gained official recognition.

CAIRO, Egypt — This Tueday, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood became a legal political party for the first time since President Gamal Abdel Nasser banned it more than half-a-century ago. The military officers managing Egypt’s transition out of the Age of Mubarak approved the Brotherhood’s new Freedom and Justice Party, the Islamist organization’s chosen vehicle to political power.

After decades in limbo, the Muslim Brotherhood will now have all the benefits of unambiguous legal status — and face all the scrutiny and questioning to which a political behemoth is subjected. The Brotherhood has built its considerable following, and honed its impressive organizational wherewithal, by striving in the shadows against a police state’s full force.

During their decades under the ban, Brothers spread their religious message and delivered what services they could. Now, however, the challenges are vast and political, and the underground methods of a doctrinaire religious group (whose primary mission, always, was spreading a strict message of faith) won’t play the same way on the political stage.

It’s a confusing transition for the Islamist activists trying to reposition their organization from oppressed social group to political strongman.

Egypt on the John Batchelor show

John Batchelor asks me about Egypt’s constitutional debate on his show; clip starts just after the 19:00 mark.

The Revolution Pushes On

CAIRO, Egypt — The Egyptian uprising that began on January 25 has yet to reach its zenith. Many an acerbic observer has noted that so far it has yielded little more than a personnel change in a military dictatorship. That same cynicism, of course, misled many Egypt-watchers when the protests first began, discount the potential of people power to force change. Oddly, the same demerits summoned then are now cited as proof that Egypt has not really witnessed a revolution or that its revolution is in disarray. The main allegations: the popular movement against the regime lacks a leader and a coherent plant; it relies too much on elites; its criticisms of the military will alienate most Egyptians, who just seek stability; and that the military is more firmly entrenched in power than ever before.

Consider the significance of Friday, when one of the largest protests in Tahrir in months drew the full, preemptory wrath not only of the military junta, but of the Muslim Brotherhood. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF, addressing the multitudes in the traditional intimidating rhetoric of Egypt’s ruling class but through the modern vehicle of its Facebook page, warned about “suspicious forces conducting acts that will cause tension between the Egyptian people and the armed forces.” Several activists, including a trio of artists, had been arrested the week before while promoting the march, and the military ominously warned it would stay away from Tahrir, and that thugs might run rampant. This last declaration was taken as a hint that the military might be reviving one of the regime’s oldest tricks, pulling security off the street and then deploying its own paid baltagaya to beat and harass dissidents.

For its part, the Brotherhood, the only formidable political organization outside the state, has shown itself cynically willing to play footsie with the junta while discrediting its erstwhile revolutionary confreres. “At whom is the anger directed?” the Brotherhood leadership asked in a patronizing statement in which it explained why it would boycott the May 27 Tahrir protest, which it viewed as an unacceptable rebuke toward the military — or what it considers the unassailable sentiments of the “majority” of the Egyptian people.

These are old tropes, echoing a favored ploy of Mubarak, his predecessors, and many of his surviving colleagues in the fraternity of Arab dictators: if you want stability, behave and do as we tell you — otherwise, drown in chaos.

The youth leaders who galvanized the May 27 protest are anything but uniform or centrally organized. They included leftists, socialists, nationalists, and Islamists. The only thing they shared in common is a belief that mass protests have proven the only effective tool in winning concessions from the SCAF. Beyond that, their platforms and styles diverge. Leaders of the April 6 youth group are concentrating on a program of public outreach to convince Egyptians that only an end to de facto military rule can save the economy and their livelihoods. Many of the liberals have their eyes on upcoming elections, and are jockeying their newly formed parties for position, or arguing about the correct order for a transition: elections first, then a constitution, as the military suggests? Or vice versa? Muslim Brotherhood youth leaders brought out hundreds of their own members in solidarity and to tell their own leaders that the organization cannot function internally as a dictatorship.

Gaping questions face the revolutionary movement going forward. Can it force the military to back down on current practices that include censoring the media, trying civilians in military courts, drawing the rules for elections and political party formation by fiat, all while allowing the police to stay home and the economy to drift?

Now What?

In The Boston Globe I write about the competing schools of thought over what Egypt’s next government should look like. This debate will only get more complicated as the year wears on, with different philosophies vying for predominance on the surface, while powerful and silent vested interests struggle for power below.

CAIRO — Traffic stopped in Tahrir Square during the revolution, but four months later, the torrent of marching humans that briefly made Cairo a world symbol of the thirst for justice has been replaced by the familiar, endless stream of grumbling cars.

The tricolor paint on the city’s trees, applied with gusto in the immediate weeks after President Hosni Mubarak resigned, has already begun to fade. As the wilting heat approaches its summertime averages in the 90s, vendors here do a brisk business selling “I [heart] Egypt” T-shirts, mock license plates commemorating the date of the uprising, and posters of the young martyrs to Mubarak’s security forces.

Schools have reopened; births and deaths are once again registered by Egypt’s ubiquitous bureaucracy; and the machinery of state continues to deliver the basic services that make this nation of 80 million function. The military junta that replaced Mubarak polices the streets and censors the media, though with a touch slightly lighter than Mubarak’s. There are still street demonstrations; on most Fridays, small factions chant in Tahrir Square and distribute leaflets demanding to put figures of the old regime on trial, fix the broken economy, or allow greater freedom to criticize the government.

Most of the nation’s energy, however, has shifted to a new debate: what should come next. Egyptians are realizing that they now face a challenge perhaps even more historic than its revolution. They need to design, nearly from scratch, a legitimate state to govern the most populous Arab nation in the world.

Egyptians are supposed to write a new constitution sometime this fall. And although no one is sure precisely how this will occur — the schedule is controlled by the military junta, which communicates chiefly through updates on its Facebook page — the public conversation has already metamorphosed into raging debate over what the government should look like. The outpouring of public frustration that reached a crescendo in Tahrir Square on Feb. 11 has now moved onto a crowded lineup of television talk shows and the cafes. As youth activist Ahmed Maher put it over a demitasse at the Coffee Bean this week: “Before the revolution, everyone talked about soccer and drugs. Now they talk only about politics.”

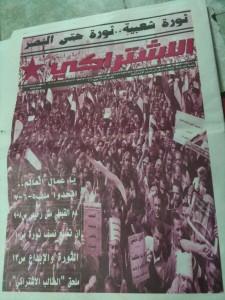

Egypt’s Socialist Media Scene

That’s right, not social media, which is all the rage among the global cognoscenti, but socialist media.

Egypt’s small but dedicated Center for Socialist Studies (a think-tank-like organization that’s hoping to create a Workers Democratic Party) has been reconsidering its approach since the January 25 revolution here. At a meeting on Tuesday night, a core group of about a dozen movement activists debated the party’s media strategy. It was but one of many manifestations of the flowering of political activism across Egypt; on this night alone, dozens of youth movements of different stripes were holding similar meetings.

The latest issue features a distorted and colorized crowd shot from Tahrir Square, with the tagline “Popular Revolution … Revolution Until Victory.” The table of contents leads with a section called “Workers of the world unite,” which can can be round on pages 5 through 7.

“We have to reach the people using the same tools as the government and the upper-class media: television and Facebook,” said Ibrahim AlSahary, a journalist whose passion is socialism. He believes that class warfare between officers and enlisted men will ultimately hobble Egypt’s military rulers and open the way for civil rule – and he thinks socialists can foment that division.

Another journalist, Bisan Kassab, fought to get a word in edgewise during Ibrahim’s discursive flights of oratory, tailored more for a parliamentary chamber than the austere meeting room near Giza Square.

“Most people don’t believe in class warfare,” she said. “We need to talk about things people care about, in language people can understand.” Bisan also wanted the meeting to deal with its actual agenda. The Socialist, she pointed out, was unreadable, its bleak layout showcasing tendentious articles about abstract socialist theory. Couldn’t the paper publish engaging feature articles, and cover news that’s actually happening?

“People want to be informed,” she said. “Let’s inform them.”

“People want to be informed,” she said. “Let’s inform them.”

An American socialist who writes for the International Socialist Worker, nodded approvingly. “This is the beginning of the revolution,” he observed.

Ahmed Shalabi, 27, an unemployed newcomer to the Socialist Party ranks, quivered with excitement. He wore a polo shirt with horizontal purple stripes and colored eyeglass frames; several people in the room mistook him for a precocious teenager. He had been distributing his own tracts in Tahrir Square a few weeks ago when he meet Ibrahim, and he found the socialist platform simpatico. He already had submitted several pieces to the newspaper’s editor and was dismayed to have received no response.

“People have been sleeping, almost dead for thirty years,” Ahmed said, in his high, almost sing-song, voice. He wants the paper to write about abuses of authority by the military, and its continuing rule under an exceptional state of emergency.

“People my age want our voices heard. We don’t understand what you mean when you talk about counter-revolution, because your language is too complicated,” he said. “We can’t just talk to our friends.”

The Shiny New Muslim Brotherhood

The Muslim Brothers hosted their grand coming-out party on Saturday night. Officially, the occasion marked the opening of their new headquarters, a seven-story monstrosity that looks like an egg-cream ziggurat on a breezy plateau above Islamic Cairo. Unofficially, the event was a declaration that the Brothers have arrived and will be kingmakers during Egypt’s season of political change.

“We’re not banned anymore,” exulted Mohsen Radi, who served a turn in parliament as a representative of a Delta town called Banha. “By the grace of freedom, by the grace of the revolution, we have regained our place.”

As symbols go, the building and its inaugural could not have been more potent. For decades, the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide operated out of a stuffy, dark, low-ceilinged apartment on the isle of Manial, in Cairo’s center. A team of state security men loitered out front. Entering visitors had to clamber over the pile of shoes in the hallway, between the elevator and the door. Senior officials would conduct interviews in the corner of the same room where the rest of the leadership was deliberating.

It was, to say the least, a no-frills operation, highlighting the Brotherhood’s ambiguous status as a legally prohibited but semi-tolerated organization.

Between 2005 and 2009, when the Brothers held 88 parliamentary seats, the organization opened a slightly more spacious parliamentary office nearby. State security forbade them from organizing any large public events, and even their annual Ramadan iftaar was cancelled. During functions there, the power often mysteriously cut out, with a frequency that the Brotherhood accepted as one of the more petty manifestations of state harassment.

Now, however, the Brotherhood is freely exercising its organizational muscle. Since Mubarak was run out of office, the Muslim Brotherhood has opened offices in every province. It is launching its own satellite television network. It has entered coalition talks with other groups, and has founded its own political party, called Freedom and Justice, which has a Christian vice president. At first, in an effort to comfort worried Christians and secularists, the Brotherhood said it would contest only 30 percent of the seats in parliament, and wouldn’t run a presidential candidate. Last week, it raised the ante, now saying it will compete for half the parliamentary districts.

With the opening of the new official headquarters in Moqattam, the transformation is complete. Bright lights illuminate the party logo in English and Arabic – a pair of green crossed swords.

About a hundred movement activists prayed outside before the official opening on Saturday night (the building’s been in use for weeks already). They chanted the Brotherhood motto in unison:

God is great.

The Prophet is our teacher.

The Koran is our constitution.

Jihad is our way.

Martyrdom is our goal.

Then they stormed into the building and emptied trays of fruit juice.

In a sign of the Brotherhood’s political heft, a parade of notables came to pay respects, including presidential front-runner and former Arab League chief Amr Moussa and a coterie of other secular politicians and judges.

In a rear lot behind the headquarters, more than a thousand supporters assembled in a dirt lot covered with carpets for the occasion. A band sang paeans to freedom, brotherhood, and the Brotherhood.

Khairat Shater, a millionaire and number-two official in the Brotherhood credited with being one of its most powerful fixers, grinned just beside the stage.

“Where do you think state security is now?” I asked. At the last Brotherhood function I attended, an iftaar in the parliamentary offices in August, the number of plainclothes intelligence officers hovering around the event equaled that of the Brotherhood officials inside.

“They haven’t gone home,” he said. “They’re around here somewhere.”

If one were keeping score, however, the Brotherhood would look to be ahead.

How Obama Played in Cairo

Obama’s speech was not all the rage in Cairo today. Many of the youth activists I know weren’t even planning to watch the speech. The US embassy organized a viewing party in a downtown hotel ballroom, drawing just over a hundred Egyptians.

“It’s a little late, but I think Obama is finally trying to get on the right side of history,” said Heba Ghannam, who pays her rent working as a corporate marketer but exercises her passion for politics by tweeting, as she did throughout the speech.

As far as Egypt is concerned, Heba wants one thing from Washington: pressure on the Egyptian army to back out of politics rather than consolidate a “soft dictatorship.” Nothing in the speech convinced her that Obama planned to put muscular American pressure on the generals who still run Egypt.

With this crowd, the president had only two applause lines (which I discussed today on Here & Now with Fawaz Gerges). His declaration that the United States would forgive a democratizing Egypt’s debts drew tepid clapping. His endorsement of Palestinian borders based on the 1967 line sparked thunderous noise and catcalls.

After a few seconds, though, the crowd returned to its staid, if mildly cheerful, pose.

“No surprises. I liked the tone,” said Nagham Osman, a 30-year-old film director.

An embassy worker standing in the back of the room nodded with satisfaction, following the running commentary of his friends on his smart phone.

“Nothing is guaranteed,” he said with a shrug. “We need to see actions.”

Intelligent Design

Can spies do a better job predicting the future and understanding the present? A bunch of social science academics think so, and they’ve outlined a host of ways to fine-tune the American intelligence community’s notoriously jagged record of spotting chthonic trends in geopolitics. My latest column in The Boston Globe describes the movement by behavioralists to bring a little rigor to spying by, well, applying the scientific method.

The American intelligence system is the world’s most sophisticated surveillance network, costing $80 billion a year with 200,000 operatives covering the mapped world, but its work can read like a grand comedy of errors. Notwithstanding all the things America’s spies get right, it’s hard to ignore the unending parade of major, world-changing events that they missed. There was the failure to connect the warnings before 9/11; the false guarantee that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction; the assured stability of Arab autocrats up until this January.

In the last decade, the network has only continued to grow, with a key role in informing decisions of war and peace, and the near impossible task of preventing another terrorist attack on American soil. With so much at stake, you would assume the intelligence community rigorously tests its methods, constantly honing and adjusting how it goes about the inherently imprecise task of predicting the future in a secretive, constantly shifting world.

You’d be wrong.

In a field still deeply shaped by arcane traditions and turf wars, when it comes to assessing what actually works — and which tidbits of information make it into the president’s daily brief — politics and power struggles among the 17 different American intelligence agencies are just as likely as security concerns to rule the day.

What if the intelligence community started to apply the emerging tools of social science to its work? What if it began testing and refining its predictions to determine which of its techniques yield useful information, and which should be discarded? Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper, a retired Air Force general, has begun to invite this kind of thinking from the heart of the leviathan. He has asked outside experts to assess the intelligence community’s methods; at the same time, the government has begun directing some of its prodigious intelligence budget to academic research to explore pie-in-the-sky approaches to forecasting. All this effort is intended to transform America’s massive data-collection effort into much more accurate analysis and predictions.

“We still don’t really know what works and what doesn’t work,” said Baruch Fischhoff, a behavioral scientist at Carnegie Mellon University. “We say, put it to the test. The stakes are so high, how can you afford not to structure yourself for learning?”

RIP

Many people have put together wonderful tributes to Tim Hetherington and to our friend Chris Hondros, killed yesterday in Libya. Chris was not only a great photographer but also a good man, with reservoirs of humility. He had a surprising interest in teaching his craft to others and explaining the stories he felt compelled to cover to audiences back home. When I think of his photographs, I first think about the spirit with which he worked, his warm Southern greeting and his ready hug. The first image that comes to mind – if only for its impact – is of the girl outside Mosul, just orphaned by American soldiers at a checkpoint.

Take a close look at the work of these two war reporters. With their deaths, we have lost far more than just two souls.

– “Diary,” Tim Hetherington’s haunting recent film about the dislocation of working in war zones and in New York City.

– Chris Hondros’ last file for Getty

– Some retrospectives of their work on the Lens Blog (Tim, Chris), and elsewhere.