Tahrir Today

On my first day in Tahrir Square, General Hassan Ruweini broke through the barricades in one-man charm and intimidation offense, which I’ve written a piece about that should be posted shortly on TheAtlantic.com. Here’s what it looked like from my vantage point as General Ruweini lectured the hostile crowd, and below, the northernmost barricade.

A Comeback for Isolationism?

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I write about a group of critics I think of as “new isolationists” — cosmopolitan and balanced advocates for a modest, demilitarized, less interventionist American foreign policy. They’re urbane, they care about the world, but they think America meddles far too much — a level of interference that hurts America as much as the rest of the world.

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I write about a group of critics I think of as “new isolationists” — cosmopolitan and balanced advocates for a modest, demilitarized, less interventionist American foreign policy. They’re urbane, they care about the world, but they think America meddles far too much — a level of interference that hurts America as much as the rest of the world.

These old-school realists come at the question from different perspectives but they all share in common a willingness to challenge the received wisdom about America’s approach to the world, and to question whether militaristic interventionism objectively has helped or harmed America’s economy and security. Their critique has matured in the decade since 9/11, and the time is ripe, I think, for us to reconsider their arguments.

There are few ways to get Democrats and Republicans to agree faster than by bringing up national security. Should America invest in a dominant, high-tech military? Should it spend time, treasure, and lives intervening in distant lands and protecting allies? Almost always, the short answer is a resounding yes. Ever since President Franklin Delano Roosevelt browbeat the skeptics and brought America into the Second World War, the country’s foreign policy has been robustly — some would say aggressively — interventionist.

Disagreements have flared only over the details: where to intervene and with what tools. Especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, both right and left took for granted America’s position as lone superpower — and that securing America required complex engagements in global conflicts. There’s mainly a difference in tone between “liberal order building,” Princeton grand strategist G. John Ikenberry’s proposal for how America should reestablish its global position, and conservative historian Robert Kagan’s unapologetic demand for American “primacy.”

This consensus in the world’s leading economy has underwritten an unparalleled military that can strike anywhere in the world. The United States has invested trillions of dollars in projecting power, and immeasurable amounts of political capital fulfilling what it considers its rightful, if exhausting, role. Its policy makers have assumed that America must police disputes from the Straits of Taiwan to the Straits of Hormuz. The next 10 largest militaries combined do not equal America’s in size, expense, or power.

But all that glitter obscures a glaring failure, according to an increasingly energized phalanx of critics. While their prescriptions vary, they all believe America suffers from imperial overreach, fighting abroad to the detriment of prosperity at home. MIT’s Barry Posen has been developing “the case for restraint,” calling for the “stingy” use of military power. Boston University historian Andrew Bacevich argues in his latest book, “Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War,” that America has become a national security state addicted to military interventions that justify its vast defense apparatus. And the University of Chicago’s John Mearsheimer, in the latest issue of the National Interest, charges that American interventionism creates more threats than it neutralizes. They, and a handful of other thinkers, say that America needs to stop meddling far and wide and concentrate on its forgotten, core interests — if it is not already too late. “The results have been disastrous,” says Mearsheimer.

Fresh Air

Terry Gross interviewed me on Fresh Air today about the events in Egypt and their potential to create new space in Arab politics. From the Fresh Air website:

All of our assumptions about the Arab world have been turned on their heads in the past month, says veteran Middle East correspondent Thanassis Cambanis.

“Everything that the experts say and everything that the activists and politicians have taken for granted for a generation, at least, is really off the table,” he tells Fresh Air‘s Terry Gross. “What’s been happening, first in Lebanon and then in Tunisia and now in Egypt and who knows further afield, suggests that new forces have been unleashed and we have no idea where they might lead and what new dynamics they might create.”

On Wednesday’s Fresh Air, Cambanis puts what has been going on in Egypt in a historical context — and explains the rising influence of the political party Hezbollah in the region. He says the recent explosion of popular anger and activism in Egypt opens up the possibility for a new political movement — one not endorsed by autocratic regimes or rooted in Hezbollah’s Islamist ideology.

“There are a lot of people, both dispossessed and powerful, who want dignity but they don’t necessarily want endless war — which is what the Hezbollah school of thought advocates,” he says. “I think they would be hungry for, and very receptive to, an Egypt-centered political movement that talks about Arab empowerment but not endless war.”

Waiting for Mubarak

Mubarak’s speech tonight eerily evoked the tone of Iraqi Baathists in the spring of 2003. Even after Saddam had fled and American troops had occupied Iraq, I met Baathists in Baghdad who spoke to me with supreme confidence about their natural role running Iraq. They had no doubt that they would remain in charge, one way or another. It took them years to realize how much their nation had changed – and that the Iraqi people didn’t want to be ruled by some reconstituted version of Saddam’s regime.

Mubarak’s speech tonight eerily evoked the tone of Iraqi Baathists in the spring of 2003. Even after Saddam had fled and American troops had occupied Iraq, I met Baathists in Baghdad who spoke to me with supreme confidence about their natural role running Iraq. They had no doubt that they would remain in charge, one way or another. It took them years to realize how much their nation had changed – and that the Iraqi people didn’t want to be ruled by some reconstituted version of Saddam’s regime.

I don’t mean to compare Saddam to Mubarak, only to point out the parallels in the process of regime detachment, teetering, and imminent implosion. It’s possible that Mubarak’s advisers have shielded him from an accurate assessment of the events of the last week, and that he has a distorted picture of the size of the crowds, their sentiment, and the dim reputation of the Egyptian state among its own people.

For three decades, Mubarak has successfully convinced some of Egypt’s elites, and much of the West, that the only choice lay between his dictatorship and Islamic fundamentalists. Mubarak offered continuity and cooperation for the United States, but little else, since Egypt under NDP rule shrank in every indicator (political influence, economic growth, regional influence). The other option in this belabored formulation was a violent, extremist Islamist Egypt ruled by the likes of Ayman Zawahiri.

In reality, however, there was no political space in Egypt whatsoever beyond the platform the regime accorded itself and its organs. The Muslim Brotherhood and the officially sanctioned opposition were only able to function in public within the limited confines permitted by the regime. Consequently, their political development was stymied.

Right now, political space has opened for the first time. The loudest voices within it come from unknown Egyptians, and not from the activists and cadres who have toiled for years in the state-sanctioned opposition. Their preferences are little understood, and perhaps not yet fully developed. They want Mubarak gone, and they seem to want his coterie out as well. They want some form of accountability. Beyond that, we have no idea if they’re interested in forming new political movements and ideologies, or whether they will forge a new way in Arab politics, some platform of ideas distinct from Islamism and secular statist autocracy. If they do, we can guess it will sound less friendly to Washington and Israel than Mubarak’s regime did, and we can also guess it might have a more religious and populist tone. Beyond that, though, there’s little yet to suggest what real representative politics will sound like, or what kind of government might take shape, or what its foreign policy might be.

There is reason to believe, however, that a post-Mubarak and post-Days of Rage Egypt might be able to deliver some improvement in living conditions, morale and perhaps regional leadership to the Egyptian people — if only by dint of trying. And so far, there’s no reason to expect that the mass of protesters, and the inchoate political realm coalescing in its wake, will agitate for war and instability. They seem bent on living better than they have under Mubarak’s rule, not on recreating the 1960s and 1970s.

Things We Don’t Know

The unraveling of Mubarak’s regime has proceeded at a tremendously exciting pace over the weekend, spawning news, uncertainty, as well as a layer of ideologically-motivated posturing in the U.S. that is only confusing our still-murky view of the situation.

The unraveling of Mubarak’s regime has proceeded at a tremendously exciting pace over the weekend, spawning news, uncertainty, as well as a layer of ideologically-motivated posturing in the U.S. that is only confusing our still-murky view of the situation.

We still don’t have a full picture of exactly what’s happening now in Egypt. We don’t know what’s happening inside the military and inside the top levels of the regime. We don’t know exactly what kind of schemes the police have implemented, although there’s evidence of undercover cops looting and trying to provoke chaos. We don’t know how motivated the protesters are to organize for the long term – although we do know their actions until now have defied almost all expert predictions. We don’t know how many people have been killed and arrested. And we hardly know what’s happened beyond Cairo and Alexandria. We don’t know how it will all turn out.

Given that vast uncertainty, it’s all the more important that we don’t let ideologues exaggerate what we do know, or paint false pictures of the players involved. We do know that almost all of the protests have eschewed the language of Islamism, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the weak establishment opposition parties. We do know that most Egyptians don’t consider Mohammed ElBaradei an inspiring or charismatic figure, and that until this weekend most activists (secular as well as Islamists) viewed his year-long debut in Egyptian politics with disappointment or even frustration. We know that the Muslim Brotherhood has been reluctant to challenge Mubarak’s regime – declining to join bolder secular parties in boycotting last fall’s parliamentary elections, and sitting out the first rounds of the “Days of Anger” this January. Finally, we know that Egypt’s suffocated civil society boasts only a few institutions with national organizational reach: the military, the state security organs, the ruling National Democratic Party, the Muslim Brotherhood, and possibly the Coptic church. Even if they play little or no role in the protests, they’ll be positioned to capitalize most quickly on a post-Mubarak order.

When an authoritarian state collapses, it’s wise to watch players with existing capacity. It’s even wiser to recall that all bets are off. Once-omnipotent secret police can vanish in a day (it happened in Iraq in 2003). New populist parties can quickly emerge. Dormant or smothered institutions like labor unions can quickly reemerge with vigor, and new political parties can spring up to tap public sentiment. Forces like the popular committees organizing to protect Egyptian neighborhoods from looters and the police could easily morph into a potent political force.

So ignore anyone who tries to paint the situation today in Egypt as a simple struggle between a moderate authoritarian regime led by Mubarak and a fanatical Muslim Brotherhood poised to lead Egypt into war with Israel. That regime, as it existed until last week, will be forever changed by the Days of Rage if it survives in some form or another under President Suleiman. Multiple unknowns surround a Muslim Brotherhood that has acted anything but radical in the last three decades, but that’s largely beside the point; the Brothers simply don’t have the numbers or the dynamism to take over this popular revolt. They’ll be a key stakeholder in any new order, but there’s no evidence to suggest they’ll play a dominant role. The military will still be there next month. So will the labor unions, and so will the privileged class that backed Mubarak’s regime and which in Egypt’s next iteration will still channel much of its economic and political power. Egypt’s history of secular nationalism will surely shape events, as will a surging popular will that until last week was almost entirely a mystery.

Hezbollah and the Tribunal

A few weeks ago, when Lebanon was still big news, I gave a talk at the International Peace Institute in New York. They have posted a podcast and transcript of the remarks, moderated by Warren Hoge and punctuated witha very lively question-and-answer question, with some smart pushback from audience members who thought I overstate Hezbollah’s ideological motives and understate the extent of the party’s Lebanonization.

History’s Side in Egypt

The popular uprising in Egypt today will conclusively change the political dynamics in the most populous Arab country, no matter what the short term outcome. Hosni Mubarak might hang on to the presidency for some time, but the parameters have radically changed. (I can’t take my eyes off Al Jazeera.)

The popular uprising in Egypt today will conclusively change the political dynamics in the most populous Arab country, no matter what the short term outcome. Hosni Mubarak might hang on to the presidency for some time, but the parameters have radically changed. (I can’t take my eyes off Al Jazeera.)

In August and September, all the Egyptians I interviewed about their country after Mubarak ruled out mass protests as even a remote possibility – especially mass protests not organized by the Muslim Brotherhood.

But that’s exactly what we’ve seen now; tens of thousands of people, maybe more, in virtually every major Egyptian city, willing to march and knock heads and risk death to call for an end to Mubarak’s rule. They’re not doing it under the banner of the Muslim Brothers or of the small, organized secular opposition.

So one shibboleth of Egyptian politics has been cast aside: the Egyptian people are capable of revolt.

What follows will depend on many factors: the endurance and persistence of the protestors; the choices of influential politicians, in and out of the regime; and most of all, I think, the choices the military makes.

Right now, police and intelligence run Mubarak’s police state. The military governs its own fiefdom, and considers itself the steward of the nation’s sovereignty. As retired General Hosam Sowilam told me this summer, in a time of transition the military “shall obey the president because he will be accepted by the people. But we will not accept any interference by the political parties into our military affairs.”

If the people withdraw their support from Mubarak, I guess the military will see its advantage in standing with them and not with the regime. In terms of bald self-interest, the military will want to maximize its influence with whomever follows Mubarak. That’s similar to the choice Tunisia’s military made.

A handful of power centers can play a role in crafting an alternative to Mubarak’s rule: Egypt’s intelligence chief; the military; the interior ministry; and to a lesser extent the institutions of civil society, both pro- and anti-regime: the NDP, the Muslim Brotherhood, the secular opposition parties, the protest movement, ElBaradei’s organization. Only the military has the weight to tilt the balance on its own.

Postscript on Twitter in Tunisia

Tunisia’s popular uprising began in December when a man set himself on fire in protest against a repressive, US-allied government. Quickly, one man’s gesture sparked a national movement that within a month toppled a dictator, a first-time event for the Arab world.

Tunisia’s popular uprising began in December when a man set himself on fire in protest against a repressive, US-allied government. Quickly, one man’s gesture sparked a national movement that within a month toppled a dictator, a first-time event for the Arab world.

Even before the fleeing autocrat had found refuge in another country, internet boosters were calling Tunisia a “Twitter Revolution” and a “Social Networking Revolution.” Chroniclers of the revolt – mostly bloggers and journalists – traced the revolt to disclosures from Wikileaks that quickly spread among Tunisians through Facebook and Twitter. In this telling the social networking sites were pivotal to organizing the street protest that toppled the regime.

Luke Allnut on Tangled Web writes that our Western eagerness for an easy, quick explanation for a distant revolution blinds us to truer but less jazzy narratives – like the one about people in Tunisia rising up because of chronic unemployment and violent government repression. “Twitter revolution narratives are popular because rather than being about Tunisia, they are often really about ourselves,” Allnut writes. “When we glorify the role of social media we are partly glorifying ourselves.”

The enthusiasm of social media evangelizers echoed their breathless reaction to Iran’s massive anti-regime protests in 2009. Jared Cohen, a whizz kid at the State Department who put social networking at the center of democracy promotion, intervened to keep Twitter online during the protests. He made a much-ballyhooed trip to Syria promoting the idea that better web access would lead to more freedom. Last fall he left government to found a “think/do tank” for the web monolith called Google Ideas.

Clay Shirky, an NYU professor who is one of the most eminent theoreticians of the internet, argues that the tools of social network have forever altered the geography of power in the world. His view is a more staid and academic version of Julian Assange’s radical claims about the power of Wikileaks to counter American power. (He is best known for his gospel of crowd sourcing, “Here Comes Everybody,” and his latest book is “Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age.”)

A backlash has taken root though, with some serious scholars and analysts calling into question the information innovation bubble. Their counter-narrative tells a deflating story.

Malcolm Gladwell argued in a very influential New Yorker essay that the “weak ties” of Facebook and Twitter could effectively mobilize people to donate a few cents for Darfur, but only “strong ties” created by face-to-face life could inspire people to make the kind of physically risky sacrifices necessary for real protest, like the American civil rights movement.

Even less kindly, Evgeny Morozov – a scholar who has spent his career studying the effects of the internet on political life and comes across as an ornery skeptic – mocks what he derisively calls the American government’s “internet freedom agenda” as a chimera “that can boast of precious few real accomplishments.” He has just published a book called “The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom.”

* * *

I have always been slightly puzzled by the certainty of the internet-freedom-utopians, who for a decade have been blogging their revolutionary ideas about how the world wide web has created a new taxonomy of power, tilting the balance away from central venues of control and toward the little man, the anarchic hacker, the crowd.

They seem always to be posting over comfortable connections in the United States; I sensed in their vertiginous web euphoria that they were surfing at warp speed on fiberoptic networks, streaming video or music over their ample bandwidth.

In contrast, I’ve spent much of the last seven years accessing the internet from places like Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Gaza, Iraq and Lebanon. As a matter of course connections there are balky and heavily censored; watching YouTube or listening to Pandora was out of the question. Entertainment articles often fell astray of sloppy filters that target political content or un-Islamic porn. My own coverage of political events in American newspapers has been at times inaccessible to me online from the country in which I was reporting. This past summer as I covered a government crackdown on dissidents, I could follow the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights postings on alleged torture and detentions. Suddenly, the next day, their site was blocked.

Secret police loiter in the hotel lobbies; they listen in on phone calls and show up at interviews with dissidents that were scheduled by text message (this happened to me in Cairo this summer, when I met a Muslim Brotherhood webmaster). They’re carefully monitoring online activity too, and if it better suits the police state’s interests, they can sever access in an instant. Friends in Iran, Lebanon and elsewhere assumed that secret police were reading their email. Often enough the monitors would leave traces in my friends’ webmail, either out of carelessness or to send an intimidating message.

The people of Tunisia, or China for that matter, aren’t surfing our American internet. Information might want to be free, as the tech bubble generational saw has it, but many governments around the world still don’t want their people to be. Twitter and Google Chat are no match for a well-funded authoritarian ministry of the interior.

American thinkers have a tendency to project their own theories and tastes on political waves elsewhere; perhaps that explains the Twittermania and Facebook faddism over Tunisia today and Iran in 2009.

* * *

One danger that Morozov often highlights is that the more the United States interferes with an internet it doesn’t really understand, the more unintended harm it might cause.

“The Internet is far too valuable to become an agent of Washington’s digital diplomats,” he wrote in a recent Foreign Policy essay.

Secretary of State Hilary Clinton in a speech just over a year ago at the Newseum in Washington acknowledged that the same technologies that help dissidents promote accountability also empower Al Qaeda and human rights transgressors. But she contrasted the divisive symbolism of the Cold War Berlin War with the open internet, which she called “the new iconic infrastructure of our age.”

“On their own, new technologies do not take sides in the struggle for freedom and progress, but the United States does,” Clinton said. “We stand for a single internet where all of humanity has equal access to knowledge and ideas.”

The implications are stark. At best, the contrarians suggest that the web in all its incarnations and with all its tools and hype-fueled pseudo-philosophy – social media, crowd-sourcing, citizen reporting, web 2.0, the long tail, flattening the world, Skype and all the rest – are potent communication tools like the telephone and the television. What naïve boosters often ignore is that these tools and the multiplier effects they create are just as available to a repressive government looking to extend its control as they are to activists looking to overthrow it.

At worst, the internet skeptics point out, the world of web activism has disproportionately empowered despots. It gives frustrated citizens a harmless outlet to blow off steam, channeling their rage at a nasty regime into ribald blog posts rather than into underground organizing, street protests, or violent attacks that might truly threaten a police state. Even more importantly, the web concentrates opposition and other activists in forums that feel private and unified but which in fact are easily monitored and penetrated by state security. As a result, more than ever before in the wired age police states know exactly what their opponents are thinking, debating and planning.

Recent events illustrate the silliness of believing that new communications platforms have erased the advantages of old-fashioned coercive sources of power – secret police and surveillance for governments, and massive demonstrations and crowd violence for anti-government activists. Dictators in history haven’t been shamed out of office; they’re overthrown. Today, police states won’t be Tweeted, Facebooked or Wikileaked out of power either.

Theater of War, War Theater

How can theater grapple with America’s contemporary wars? What art can stem from the Global War on Terror, in its tenth year, and can artists make art out of war? More ambitiously can they make art informed by war but not necessarily set in the combat zone or among warriors?

This question propelled the organizers of a wrenching and thought-provoking night at the New York Theatre Workshop on Monday.

Emily Morse and Rachel Dickstein curated the evening, which featured short performances – extracts – from five plays, each of them engaging a question that arises from America at war (authors included Sophocles and the contemporary Pulitzer Prize winner Sarah Ruhl). All five creators (a blend of playwrights, directors, actors, classicists and documentarians) were attractively humble about their enterprise, and for the most part avoided didactic politics and manipulative emotions.

What it highlighted for me – as a reporter who spent four years focused almost exclusively on the ground level of America’s wars in the Middle East, and as a consumer of fiction, film and theater – was the absence of contemporary touchstones that can speak to and then transcend today’s American experience of war. The most powerful scenes on stage at the New York Theatre Workshop last week were set in Troy, three millennia ago. When we look for more recent works of art, we’re most likely to find something kindred, something that speaks across contexts, in the literature and film, or in Shakespeare.

Documentary has valiantly tried to fill in the gap, and has yielded some astoundingly powerful works – Waltz With Bashir and Restrepo leap to mind – but the first addresses Israel’s memory of Lebanon in 1982 and the second accomplishes much of its magic by staying close to the young men in the Korengal Valley and away from our complicated position here at home.

Guilt, or cloying sentimentality, has spoiled most of the Hollywood movies about this last decade of war; the best of the bunch as a war story was the fantastical “Hurt Locker,” which succeeded by mining combat for high drama and successfully composing psychologically compelling portraits of its twentysomething fighters. Broadway hasn’t done much better, although from across the Atlantic we got the fabulous “Black Watch” from the National Theatre of Scotland.

VETERAN VOICES

Monday night’s lineup in New York suggested that we’re growing past the first stirrings, and can soon expect some ripe, historically grounded, efforts to speak to our collective experience.

“ReEntry” presented the exact words of Marines interviewed after their return from Iraq and Afghanistan. The authors, Emily Ackerman and KJ Sanchez, both come from military families and ReEntry was clearly a personal labor, executed with love and without judgment. An officer speaks with dry military humor about what it takes to hold it together while fighting, or while waiting back home for a fighter; in one of the biggest laugh lines of the night, he tells people to keep their predictions to themselves “unless you’ve got a crystal ball up your ass.” A Marine raves about the dumbass kids in skater pants, all the stupid Americans who have no idea what’s happening in America’s war zones on the other side of the globe. A woman Marine notes that when she’s out at a bar with her male buddies, strangers buy them all shots – all but her, because they assume she must not be a fighter. A wife jumps into bed and her husband, dreaming of some distant threat, chokes her. He wakes up and apologizes, devastated. “It’s my fault,” she says.

These are telling snippets, scenes from a war, and they hover in a liminal zone between documentary, journalism and theater. They are performed with vigor and humanity, and they are true; they are engaging and socially useful, as a conversation with a real war vet would be. For those who never have met a contemporary American warrior or one of their immediate family members, these will be illuminating monologues – but I’m not sure they’re art.

Kia Corthron’s “Moot the Messenger” was harder to judge; it’s early in production, so we see seated actors read a dramatic physical scene, barely making eye contact with each other. This play brings a journalist and her brother together at the family house, somewhere in the American south; both have been working in Iraq, one as a reporter, the other as a soldier (or Marine, it’s unclear). The brother has lost his legs to friendly fire. He’s bitter and volatile, his sister seems muted with guilt. Their father – a Korea vet – fears telling jokes anymore, and never told his son a single thing about his own war. In a few minutes, the dialogue raised so many political questions, and veered into violence with plates and glasses smashing and the siblings screaming, that in this reading “Moot the Messenger” felt as heavy-handed and political as its title.

BACK IN TIME

Then the evening took a welcome turn; we do better at addressing our present, I suspect, when we look to the past, which felt more and more contemporary the farther we got from the present day. We began to get stories with war in them, rather than war awkwardly packaged into a story.

“Septimus and Clarissa,” adapted from Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, gives us the madness of Great War veteran Septimus Smith. You say shell-shocked, I say PTSD. (The Ancient Athenians sometimes described a fog settled around the head of a warrior by a god, temporarily blinding him to reality; other times they referred simply to madness or rage.) All different tags for the same spoiled, ubiquitous ware of war; the battle psyche, scarred sometimes in the trenches, sometimes back at home, from afar. Septimus cannot see his wife, or London, because he hears birds calling in the voice of the friend who died in the trenches; the twitters are calling him to take his own life.

In Sarah Ruhl’s “Passion Play,” a Vietnam veteran returns to South Dakota and meets his three-year old daughter for the first time. He bumbles and fumbles, scares her with a game of airplane; he cannot touch his wife or let her touch him; finally he lays down for the night on the doorstep. He cannot cross his hearth. In a haunting piece of magical realism, his daughter comes to him in the night. He imagines that he controls the wind; she tells him she is a reincarnated soul who died in the last year. “There’s always the next war,” she tells him before instructing him, as a child would, “Now get that war out of your head.” “How?” he asks. No one knows.

AJAX, A MODERN MAN

Wisely, the curators put Sophocles’ “Ajax” last. The extracted scene portrays Ajax just after an insane rage has lifted. The armor of his great friend Achilles, slain on the plains of Troy, is the medal of honor of the time, and should rightfully have gone to Ajax. Instead the ever-political Greek generals rig a contest, and award the armor to wily Odysseus. To reclaim his honor, Ajax swears to murder all his superior officers. The goddess Athina blinds him and directs him to a fold of farm animals instead. He butchers and tortures the animals, only to realize at dawn that he not only has lost his honor but has exposed himself as insane before his men. Even more enraged, he threatens his wife, his son, himself, proposes suicide and mass murder. His wife browbeats him to equanimity, but barely; eventually she leads him to see his son, whom she had hidden lest his shell-shocked (scratch that anachronism: make it war-drunk) father unintentionally kill him in blind rage.

At root, this is a story of a man and his wife battling each other and finding accommodation; their marriage is tender and violent, not a love match but the fruit of an invasion and raid in which Ajax killed his future bride’s father. “I have come to love you,” she says, and goes on to force Ajax to see himself from the outside. His blind rage subsides, but by no means is neutralized. Which as humans might be the best we can do: keep anger at bay, limit the channels through which war can course.

Bryan Doerries, who directed Ajax from his own translation, is no anti-war polemicist. He described himself as a defense contractor, only partly tongue in cheek. The Pentagon has given him a grant to stage his ancient Greek plays 300 times so far at military installations; in a few weeks, Doerries will be performing for the jailers at Guantanamo Bay.

If you believe in God, this is God’s work. Ajax can speak to anyone in any context, entering dark corners of our psyche that perhaps a frothing US Marine in ReEntry cannot. According to Doerries, the military audiences feel an innate rapport with the classics, and have taught him – a classicist – a new reading of the works he has translated. Fighters and their families intuitively grasp ideas like honor, sacrifice, betrayal, Platonic love, and patriotism. A wife expecting her husband back from a fourth or fifth deplyment in Iraq or Afghanistan naturally sees Ajax’s wife as an intimate confederate. They’re both loyal spouses elevated by and trapped in a military society fighting a war that appears without end.

Doerries described a woman who after a performance said, “I understand how Ajax’s wife felt. Every time my husband comes home from a war he fills our house with a trail of invisible dead bodies.” The timelessness of the story and the abstraction of the place, ancient Troy make all the more tangible its timely essence: a proud man at a loss, fighting because we want him to, damaged by the fight, ashamed of the damage.

ATHENS AND AMERICA

Unlike Sophocles’ Athens, in which everyone shared the burdens of generations of continual war, America at war today is not a nation at war; we are a nation that has asked one community to carry on our battles for us. We have segregated our Praetorian class from society at large. Military families by and large live concentrated in scattered enclaves. The rest of America experiences little organic contact with military America. This split was engineered after Vietnam, as part of the professionalization of the military and the end of the draft. It’s not accidental. It helps preserve the warrior ethos and in some ways it allows the Pentagon to better serve the families that choose the engulfing commitment of military life. It also insulates the two parallel cultures from each other.

Conversely, Periclean Athens (Pericles and Sophocles, the great politician and playwright, also served as generals), like the United States in the time World War II, was a society in which everyone knew war intimately. They fought, or their close relatives had fought, or they had lived in or near a battleground. They felt touched by war, and responsible. Death and killing and the attendant pride and trauma accompanied all of them at their dinner tables. War, for them, could never be an abstraction, or only an abstraction.

An actress who spoke to me after the performances made reference to the need for story. That, I guess, is what we need as an audience, as a nation, as aesthetic beings: not a reaction to war, but a story – a work of art – that cleanses us or better arms us to comprehend our urge to make war and how those wars spatter and power our world. At its base, war is killing, but is also a spawning. A fire consumes wood, but creates heat. War consumes life, but creates new identities, cultures, rulers, nations, powers, wealth, elites. War creates death and sometimes freedom too, if mostly negative freedom.

Instinctively, people do not like to kill; military psychologists have carefully studied the reflex of a fighter not to pull the trigger, or to fire wide even at an oncoming enemy bent on killing first. (Dan Baum chronicles the history of the US military’s psychology of killing from World War II to the present in a 2004 New Yorker article called “The Price of Valor.”) We are trained not to kill, but train ourselves to kill we must. There is a price to pay for that necessary choice, even if we try to sanitize mainstream society by building a separate channel for our warriors. That price registers not only in the seared soul of Ajax, but in that of his entire community, his wife, his son, his soldiers, his subjects back home. So, too, with us; we Americans all have a stake in today’s wars, whether we fight in theater, oppose the war at home, and especially, if we ignore the entire affair.

STORIES FOR TODAY

Those who pay little attention that their names are attached to our collective American ventures oversees – those anonymous shareholders in our shared war enterprise – are the ones most in need of an intimate touch, and they won’t find it in on talk radio or at anti-war rallies, in a sanctimonious film or even an excellent work of narrative documentary. If they find it at all, it will be through art. These five creators have begun the thankless work of finding the stories that will tell us what is happening to our culture.

When I was still living in Iraq and covering the first phase of the war there, my friends and I wondered why there were so few contemporary cultural artifacts that spoke to our experience there – as reporters, as soldiers, even as failed statesmen – or of the experience of the Iraqis we were killing and governing and fighting. There was lots of journalism, some of it excellent; and a few halting attempts to engage the war in culture. The most successful were the documentaries – No End In Sight, Gunner Palace (and recently from Afghanistan, Restrepo) – and they benefited in part from their limited remit. They weren’t trying to tell us how or who or why on the individual psychological level that is the province of art; they were simply, if ambitiously, trying to tell us what was happening: a basic whodunit.

Alicia Anstead, the culture writer who moderated the theater evening, argues that documentary absolutely is art, even if it’s not what we conventionally think of as theater. Her view could extend to all the fine arts. “It’s a legitimate approach, blending aspects of journalism with aspects of theater,” Alicia wrote me, regarding documentary as a medium for addressing society’s relationship to war. “But it’s no less theater or art than a feature article or political cartoon or ‘Shouts and Murmurs’ is journalism.”

Ten years into this very long war – America’s longest now, officially, that we’re into the tenth year of occupying Afghanistan – we need the guidance of artists. We need a Tim O’Brien, a Slaughterhouse Five, an Apocalypse Now. I’d even settle for a Three Kings or a Jarhead.

Back in 2005, we thought it would take time for art to process these wars, and maybe a certain temporal distance is necessary; we can’t heal until the killing has stopped, or gone on hiatus; we cannot storify with grace until the story has come to an end. If these wars, however, shall extend without end, or at least no end anytime soon, we can’t wait until they’re over. We need our bards and their epic tales now.

Lebanon talk on WBUR

Robin Young had me on her show Thursday to discuss my oped in The New York Times. At the end she asked me what would change if the United States changed its policy and started engaging Hezbollah. In this case, I guessed, nothing; dialogue might give the U.S. more information that it currently has, and more insight into Hezbollah than it currently possesses, but little else.

Robin Young had me on her show Thursday to discuss my oped in The New York Times. At the end she asked me what would change if the United States changed its policy and started engaging Hezbollah. In this case, I guessed, nothing; dialogue might give the U.S. more information that it currently has, and more insight into Hezbollah than it currently possesses, but little else.

Click here for our conversation.

Hulk in the the Holy Land

My friend Brian Katulis has written perhaps the most penetrating short meditation on Israel-Palestine published in quite some time — a historical look at the long conflict through the eyes of the pre-Oslo Incredible Hulk.

My friend Brian Katulis has written perhaps the most penetrating short meditation on Israel-Palestine published in quite some time — a historical look at the long conflict through the eyes of the pre-Oslo Incredible Hulk.

In “Power and Peril in the Promised Land,” Bruce Banner stows away on a ship and wakes up in Israel, where he befriends a young Arab boy who is killed by Arab terrorists. This angers Bruce, who turns into the Incredible Hulk and takes the boy’s body next door to Jordan, all the while chased by the Israeli super heroine Sabra.

One can imagine Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, George Mitchell or even President Obama sympathizing with the Hulk’s frustration found on the last page: “Boy died because boy’s people and yours both want to own land! Boy died because you wouldn’t share.”

Priceless. And timeless.

Justice deferred, or deterred?

In Lebanon, crises unfold in unbearably slow motion until a sudden, usually deadly, climax. Everyone tunes out except for the participants and the hardened, usually professional, Lebanon-watchers; it’s all tedious process until somebody gets hurt.

In Lebanon, crises unfold in unbearably slow motion until a sudden, usually deadly, climax. Everyone tunes out except for the participants and the hardened, usually professional, Lebanon-watchers; it’s all tedious process until somebody gets hurt.

That’s what happened on Tuesday when Hezbollah forced a government collapse. It sounds dramatic, and it’s a critical point in the slow boiling showdown that’s simmered for years over the International Special Tribunal on the Lebanon assassinations. Hezbollah toppling the government is just an incremental step, although a major one, in the process by which Hezbollah will try to fatally cripple the Tribunal and render Hariri incapable of governing.

Saad Hariri inherited the premiership five years after his father was murdered. In a measure of the molasses pace of Lebanese politics, it took Hariri five months to negotiate a coalition cabinet; that government barely lasted 14 months.

There are only a few viable ways for this to turn out.

1. Hariri could fully repudiate the Tribunal, withdraw Lebanese support for it, and let it die on the vine. Even if Hezbollah members are indicted, nothing will come of it. This outcome, I think, is unlikely, only because it leaves Hariri with nothing – no actual power, and no legitimacy.

2. Hariri could insist on supporting the Tribunal. Hezbollah would be forced to escalate, and might eventually use violence as it did in May 2008, when it briefly conquered West Beirut. In this case, the Tribunal would be scuttled as well, but Hariri would preserve integrity and therefore political legitimacy. In an op-ed in today’s New York Times, I argue that Hariri is most likely to pursue this course.

3. Lebanon could limp on under a caretaker government for a year or two (like it did for long stretches in 2007 and 2008), unable to cooperate with the Tribunal, scuttle it, or make any controversial decisions. This is also a very likely scenario, as David Kenner writes at Foreign Policy.

4. Hezbollah could manage to form a government with a pro-Resistance prime minister, a scenario that would probably quickly spark a war with Israel, as Juan Cole points out today.

5. Hezbollah could decide to throw some bones to the Tribunal, under pressure from Syria and/or Iran. This outcome is the least likely; there doesn’t seem to be any pressure coming from Hezbollah’s patrons to moderate in the showdown over the assassinations, in all likelihood because neither state would benefit from a full accounting of the string of murders in Lebanon that began with the Hariri killing. The entire Axis of Resistance benefits from a confrontation that strengthens Hezbollah, weakens a government allied to Saudi Arabia and the United States, and which blames Israel for all the killings in Lebanon in a scenario that stretches credulity for all audiences except the partisans of Hezbollah.

The only scenario we’re unlikely to see is one is the “full justice option”: the International Tribunal releases compelling evidence about the assassinations of Rafik Hariri and all the other anti-Syrian figures murdered since 2005; the most important suspects are arrested and put on trial; and the powerful entities with stakes in Lebanon honor the judicial process and accept its outcome. That scenario is only a dream.

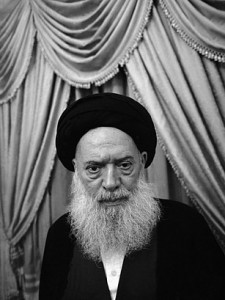

Fadlallah remembered

Just surfaced on the web, this remembrance that I wrote for Time magazine’s annual farewells issue:

Ayatullah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah survived an apparent CIA assassination attempt — a 1985 car bombing in Beirut that killed 80 people — and wore the attempt on his life as a badge of honor. The fiery cleric, whose most famous fatwa blessed suicide bombers in the war against Israel, was an intellectual pioneer of militant Islam: a brilliant jurist and tireless organizer, reviled by Washington as the spiritual leader of Hizballah.

But by the time of his death (of natural causes), Fadlallah had broken with Hizballah and the toxic legacy of his early edicts. He criticized Iran’s clerical rule, supported women’s rights and insisted on dialogue with the West. When I interviewed him, he was a soft-spoken and gracious host who enjoyed debating policy and philosophy. His passing marks a step backward for reform in the combustible world of Islamist militancy.

No Big Deal

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

The great international problems of our time beggar the imagination: global warming, pandemics, war crimes, nuclear proliferation, just to name a few. Their complexity confounds the most agile of technocrats, and the stakes involved are high, affecting billions of people living under every sort of government.

For half a century, the conventional approach to these problems has been to build massive international treaties. Intricate worldwide problems demand an integrated approach — a grand bargain, so to speak, that addresses all the winners and losers in a single, encompassing agreement.

This is the animating assumption behind the world’s approach to global warming, for example. To persuade growing nations like China to limit their consumption of fossil fuels, the thinking goes, the world needs a comprehensive framework ensuring that more developed nations make equivalent sacrifices. The climate is simply too large a problem to address piecemeal, or by tinkering with minor symptoms.

But what if this approach results in less progress? What if more modest agreements — on climate change, loose nukes, and other sweeping problems — would yield better results than a long, noble quest for a grand bargain?

Haaretz reviews APTD

The esteemed weekend Haaretz has reviewed A Privilege to Die, recommending the book to Westerners, and in particular Israelis, because it contains insights into Hezbollah that might well make readers uncomfortable. (Disclosure: the reviewer, mystery writer Matt Beynon Rees, is a friend.) He compares my book to David Hirst’s Beware of Small States.

The essence of the Shi’ite organization’s success, as Cambanis sees it, is its ability to carve out clear answers to Lebanon’s vital national questions. That gives it a big advantage over the cloudy mass of Lebanon’s other vicious sectarian parties. One voter tells Cambanis that his choice of Hezbollah was based on the fact that he was “sick of all these other assholes.”

Read the rest of the review here.

http://www.haaretz.com/culture/books/middle-east-into-the-heart-of-hezbollah-1.336038

From the Archives

I was cleaning out my office ahead of the New Year, and I found the press badge that the US military issued me in Kuwait in 2003. Just a few weeks before the invasion of Iraq, the military press office (known during that phase of the war as the CFLCC PAO) accredited more than a thousand journalists. Lots were embedding for the invasion, but plenty more of us were operating on our own. We still needed badges to deal with the ubiquitous military.

The spokesman’s office organized sessions to plan how to bring unembedded journalists to the site of the WMD he expected to be discovered. In other ways, too, the flacks were planning ahead for a long slog in Iraq: my accreditation lasted more than a year, through May 2004.

The terminology, though, still makes me laugh — the unwitting sense of humor of the acronym-happy bureaucrats who brought us hits like the quickly discarded “Operation Iraqi Liberation.” America was suffering global recriminations for eschewing allies and multilateral institutions in its march to war. With no apparent trace of irony the military’s public affairs department borrowed the term being flung at the US government by angry critics, and applied it to the reporters who had chosen not to embed: we were “unilateral journalists.” To this day it’s my favorite title I’ve ever earned.

Foreign Affairs Review

A brief mention of A Privilege to Die in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs:

Cambanis’ intimate account of this recent history, enhanced by stories of a handful of Hezbollah’s true believers and sympathizers, paints a gripping portrait of this radical religio-political movement.

WBUR’s Here & Now

Robin Young brought me into the studio on Tuesday to talk about my column in The Boston Globe about “engagement hawks,” the pragmatists who argue that America needs a more coherent strategy to deal with terrorist-designated groups and other enemies.

Talk to Terrorists

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

Ronald Reagan framed the debate over whether to talk to terrorists in terms that still dominate the debate today. “America will never make concessions to terrorists. To do so would only invite more terrorism,” Reagan said in 1985. “Once we head down that path there would be no end to it, no end to the suffering of innocent people, no end to the bloody ransom all civilized nations must pay.”

America, officially at least, doesn’t negotiate with terrorists: a blanket ban driven by moral outrage and enshrined in United States policy. Most government officials are prohibited from meeting with members of groups on the State Department’s foreign terrorist organization list. Intelligence operatives are discouraged from direct contact with terrorists, even for the purpose of gathering information.

President Clinton was roundly attacked when diplomats met with the Taliban in the 1990s. President George W. Bush was accused of appeasement when his administration approached Sunni insurgents in Iraq. Enraged detractors invoked Munich and ridiculed presidential candidate Barack Obama when he said he would meet Iran and other American adversaries “without preconditions.” The only proper time to talk to terrorists is after they’ve been destroyed, this thinking goes; any retreat from the maximalist position will cost America dearly.

Now, however, an increasingly assertive group of “engagement hawks” — a group of professional diplomats, military officers, and academics — is arguing that a mindless, macho refusal to engage might be causing as much harm as terrorism itself. Brushing off dialogue with killers might look tough, they say, but it is dangerously naive, and betrays an alarming ignorance of how, historically, intractable conflicts have actually been resolved. And today, after a decade of war against stateless terrorists that has claimed thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of foreign lives, and cost trillions of dollars, it’s all the more important that we choose the most effective methods over the ones that play on easy emotions.

Long Form Best of 2010

I’m quite honored to find my memoir of the Iraq invasion in At Length on the top 20 list for this year at longform.org. They’ve chosen quite a line-up of pieces, including a bunch I have not yet read but have just put in my Instapaper.

I’m quite honored to find my memoir of the Iraq invasion in At Length on the top 20 list for this year at longform.org. They’ve chosen quite a line-up of pieces, including a bunch I have not yet read but have just put in my Instapaper.