Rapture, Resistance, Revolution

In his review of A Privilege to Die for Global Post my friend the mystery writer (and veteran Middle East hand) Matt Beynon Rees calls attention to one the main endeavors of the book: to place front and center the regular Joes and Janes (or Ranis and Farahs) that have elevated Hezbollah into a perennial and expanding trend-setting militant movement.

In his review of A Privilege to Die for Global Post my friend the mystery writer (and veteran Middle East hand) Matt Beynon Rees calls attention to one the main endeavors of the book: to place front and center the regular Joes and Janes (or Ranis and Farahs) that have elevated Hezbollah into a perennial and expanding trend-setting militant movement.

Hezbollah’s rank-and-file, the footsoldiers and volunteers, aren’t always scheming against Israel or dreaming of perpetual war; they’re also strivers looking for better jobs, education for their kids, and a more honest relationship with God.

Because of its growth and success on the battlefield, the Party of God itself often takes on mythic status. Outsiders sometimes impute far greater cunning, skill and sophistication to Hezbollah than its occasionally clunky and authoritarian behavior merits.

Matt re-tells one of the more amusing encounters I had with Hezbollah while reporting the book:

Unsatisfied with one of his stories, Hezbollah officials denied his book the cooperation of the Party of God (“Hizb” means party in Arabic; “Allah” you probably heard of already.) He describes one party functionary telling him, “‘You can’t possibly write a book about Hezbollah without the party’s permission, right? You’ll have to move on to another project?’ Like many Hezbollah officials she overestimated the party’s ability to control or manipulate a foreigner like me and she thought the prospect of future access would tempt me to relinquish writing this book.”

Carolina homecoming

No, not that kind of homecoming.

No, not that kind of homecoming.

I’m returning to my old stomping grounds this week to visit my mother and while I’m at it, to talk about Hezbollah in Chapel Hill, Durham and Fearrington Village. These appearances complete a circle.

The last time I was in Chapel Hill as a working journalist was in 1996, as editor of The Daily Tar Heel, muckraking about developers, the BCC, the mayor’s race, NIMBY soccer moms, and “town-gown relations” (who came up with that horrifying cliche?).

Now I’m back doing the same thing, at somewhat greater length and I hope with a sharper capacity to entertain. The subjects aren’t all that different: Islamism, guerilla war, Middle Eastern politics, NIMBY soccer moms, and “Arab-Israeli relations.”

7 p.m., Thursday, Oct. 7, Flyleaf Bookshop, Chapel Hill.

7 p.m., Friday, Oct. 8, Regulator Bookshop, Durham.

11 a.m., Saturday, Oct. 9, McIntyre’s Fine Books, Fearrington Village.

Tribunal bedeviling Hezbollah

In the kind of notoriety that really excites a geek like me, my favorite blogger on Lebanon has interviewed me about A Privilege to Die. Qifa Nabki talked to me about what it is, exactly, that I’m writing and arguing about Hezbollah, and delves into some of his favorite topics – like Hezbollah’s influence on the wider Arab world and the social-ideological recipe that distinguishes Hezbollah from other mass-mobilization Islamist movements.

In the kind of notoriety that really excites a geek like me, my favorite blogger on Lebanon has interviewed me about A Privilege to Die. Qifa Nabki talked to me about what it is, exactly, that I’m writing and arguing about Hezbollah, and delves into some of his favorite topics – like Hezbollah’s influence on the wider Arab world and the social-ideological recipe that distinguishes Hezbollah from other mass-mobilization Islamist movements.

He asks how Hezbollah might respond if the International Special Tribunal investigating the 2005 murder of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri were to indict some Hezbollah members.

During my reporting trip to Lebanon in September I was surprised by Hezbollah’s uncompromising position on this issue. Party officials whom I interviewed echoed their leader Hassan Nasrallah’s absolutist stance: Hezbollah wouldn’t turn over any members, Hezbollah wouldn’t even recognize the Tribunal’s authority, and Hezbollah would ask the rest of the Lebanese government to adopt Hezbollah’s position.

If Hezbollah sticks to its guns on this issue, so to speak, it could quickly escalate into internal violence. During the crisis from 2006 to 2008, Hezbollah could argue that it was willing to negotiate so long as the other political parties in Lebanon were willing to give Hezbollah the one-third of power it was due demographically and by its share of seats in parliament. In the event of a Tribunal indictment of Hezbollah operatives, however, Hezbollah will find itself in a complicated position. If the indictment presents compelling evidence, Hezbollah will find its pure image substantially tarnished. And if Hezbollah is willing to withdraw from the government and go to war against it, rather than surrender any indicted members, it will risk alienating a broad segment of the Lebanese public that until now has supported Hezbollah’s Islamic resistance project, or at least, not stood in its way.

PTD in DC Sunday

I’ll have two public events in Washington, DC. If you’re in the area, I’d love to see you at either one. I’ll report back here on the Elliott Abrams panel, which will be live webcast at the CAP website.

5 p.m., SUNDAY, October 3: Politics & Prose (5015 Connecticut Avenue NW).

12 p.m., Thursday, September 30: Center for American Progress (1333 H Street NW). Brian Katulis moderates a discussion between me an Elliott Abrams from the Council on Foreign Relations.

NBC’s Today Show visits Mleeta

On Friday morning, I appeared on NBC’s Today Show in this spot on the Hezbollah park in Mleeta. The show visits Hezbollah’s new theme park about the Islamic resistance, the first permanent Hezbollah museum/tourist attraction.

NYT reviews PTD

Just posted, Joe Klein’s review in The New York Times Book Review.

Just posted, Joe Klein’s review in The New York Times Book Review.

Klein opens his review, entitled “The Hezbollah Project,” recounting an episode from the book about Hezbollah’s seamlessly-run intake shelter in a Beirut parking garage, to receive people fleeing the war in south Lebanon.

A metaphor, of course: Hezbollah has created a national bomb shelter in the southern half of Lebanon. Its followers are fed and cared for, and they are devoted in a cultlike way, even though many have lost family members, homes and their livelihoods because of Hezbollah’s foolish bellicosity. It is a perverse triumph. Cambanis argues, persuasively, that Hezbollah represents the most successful radical Islamist movement in the region. He also tells a story that hasn’t been told with this much attention to detail by a Western reporter before.

It’s quite a complimentary review, despite a late jab at some repetitive phrasing in chapter 1 (my commissioning editor takes full responsibility for not catching and scrubbing those early passages!).

CSM reviews PTD

Rayyan Al-Shawaf reviews A Privilege to Die in the Christian Science Monitor. He writes:

In 2006, Hezbollah launched an unprovoked attack on Israel, which retaliated massively. This war and its aftermath set the stage for the author’s searching probe into the hearts and minds of Hezbollah’s rank and file. In prose that is often eloquent yet earthy, indicative of scholarly erudition as well as a storyteller’s flair for capturing the complexities of human psychology, Cambanis describes the seemingly contradictory impulses he discovers. Consider the case of 20-something Aya Haidar, who longs for martyrdom – preferably in the throes of the soon-to-return Mahdi’s (Messiah’s) war against infidels – but simultaneously wants to marry the man she loves and start a family. Observes Cambanis: “She was a Mahdist, a Hezbollah cadre, a schoolteacher fresh out of college, and a young girl in love, rolled into one bristling ball of energy.”

He goes on to argue that the book underestimates the scope of Shia dissatisfaction with and Sunni fury toward Hezbollah, a “chink in the party’s armor” that suggests Hezbollah has at most one more war left in it. I think Rayyan (whom I don’t know personally) is right to call attention to the growing frustration with Hezbollah. On my most recent reporting trip to Lebanon in September, I found the country more polarized than ever: Hezbollah’s supporters bristling, and its detractors less sympathetic than ever toward the Party of God’s militarism.

What we can’t predict is whether another war will conclusively diminish Hezbollah, as Rayyan writes, or whether it will once again restore the party’s luster and dominant position, as it did after the 2006 war, to the surprise of so many people.

Elliott Abrams, Hezbollah and my book

I plan to write about the moderated conversation with Elliott Abrams, Brian Katulis and me on Thursday, but I wanted immediately to put up the video of the event, from the Center for American Progress website. You can watch it below or on their site.

The Half King

Monday night marked my first public presentation as a published author. Lots of friends, family, former students, and even a healthy contingent of people I’ve never met came to the Half King in Chelsea to hear about A Privilege to Die. We sold out of books, and one of my standout graduate students informed me that when I talk about Hezbollah “it’s a hell of a lot more interesting than hearing you talk in class.”

Thanks to everyone who came.

New York book debut continues tonight!

A Privilege to Die officially releases today. (Yesterday was the soft launch.) If you’re in the area, I hope you can make it:

7 p.m., Tuesday, September 28: Barnes & Noble, Upper West Side (82nd and Broadway). I’ll talk about the book and take questions.

7 p.m., Monday, September 27: The Half King Bar & Restaurant (505 W. 23rd St.). Eat, drink and ask questions about the book. We’ll stay afterward and enjoy the bar’s offerings.

Sharing the Nile

Especially in the Middle East, there are always people uttering dark apocalyptic warnings about the coming water wars. Competition over scarce oil is nothing, the thinking goes, compared to what people and their governments will do when water starts running out.

Especially in the Middle East, there are always people uttering dark apocalyptic warnings about the coming water wars. Competition over scarce oil is nothing, the thinking goes, compared to what people and their governments will do when water starts running out.

Scarcity, of course, is nothing new, and “water wars” have already been happening for some time. They’re not cataclysmic (and usually not entirely binary) like wars over a specific piece of land, which either you control, or you don’t. Israel and Lebanon have fought over a contested border with at least one eye on the watersheds and rivers on both sides. Iraq, Syria and Turkey have had problems over the Tigris and Euphrates, the present result being that the two great rivers are muddy trickles by the time they reach southern Iraq. I imagine there are countless other examples.

Egypt is now contending with the end of its own era of water abundance. A colonial-era treaty gave Egypt and Sudan 80 percent of Nile’s water. The upstream African countries are now sufficiently stable — and eager for economic development — that they have challenged this arrangement. Negotiations collapsed and now Egypt has until next May to rejoin talks, or face a new regime designed by the upstream nations in the Nile watershed.

This isn’t the kind of conflict that I would expect to spark a traditional war, but it’s uncharted, and fascinating territory. You can read more in my story from this Sunday’s New York Times.

One place to begin to understand why this parched country has nearly ruptured relations with its upstream neighbors on the Nile is ankle-deep in mud in the cotton and maize fields of Mohammed Abdallah Sharkawi. The price he pays for the precious resource flooding his farm? Nothing.

“Thanks be to God,” Mr. Sharkawi said of the Nile River water. He raised his hands to the sky, then gestured toward a state functionary visiting his farm. “Everything is from God, and from the ministry.”

But perhaps not for much longer. Upstream countries, looking to right what they say are historic wrongs, have joined in an attempt to break Egypt and Sudan’s near-monopoly on the water, threatening a crisis that Egyptian experts said could, at its most extreme, lead to war.

“Not only is Egypt the gift of the Nile, this is a country that is almost completely dependent on Nile water resources,” said a spokesman for the Egyptian Foreign Ministry, Hossam Zaki. “We have a growing population and growing needs. There is no way we can accept this kind of threat.”

Egypt’s military II

Michael Hanna elaborates his views on the Egyptian military’s role in a presidential transition at Democracy Arsenal. He brings up some of the crucial Mubarak era history (which I didn’t have room for in my NYT piece on the subject), in particular President Mubarak’s 1989 firing of the popular defense minister, Field Marshal Abu Ghazaleh.

Michael Hanna elaborates his views on the Egyptian military’s role in a presidential transition at Democracy Arsenal. He brings up some of the crucial Mubarak era history (which I didn’t have room for in my NYT piece on the subject), in particular President Mubarak’s 1989 firing of the popular defense minister, Field Marshal Abu Ghazaleh.

Michael writes:

It is hard to pinpoint the parameters of the military’s power within Egyptian society at this juncture. Yes, it is the most respected and coherent organization in the country, but Egypt does not fight wars anymore and the military is not involved in the day-to-day of politics. And, it has not been overtly involved in a presidential succession since 1952. While Anwar al-Sadat and Hosni Mubarak were both military men, they were hand-picked as vice-presidents by the president. There was no real process for the military to be involved beyond the sort of informal vetting that might have taken place internally prior to the their appointments. And it is also worth remembering that both al-Sadat and Mubarak were seen as weak figures with no broad popular legitimacy at the time they assumed the presidency, and, yet, the military regime did not attempt to block the ascension of either man to the post.

From an institutionalist perspective, the central question about Egypt remains what pathways exist beyond the mechanisms of power controlled personally by Hosni Mubarak. In the case of the military, it appears that its power must be substantially weaker than it was in 1970 or 1980, but how much weaker, and what control it has, are open and vital questions.

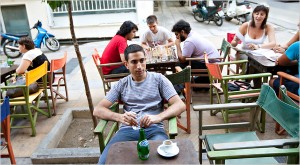

Another Greek Exodus?

While I was traveling I missed this fine story by Niki Kistantonis about the newest generation of Greeks flooding abroad because of the lack of opportunity. For much of its modern history, one of Greece’s most successful exports has been its young. It’s a common story in underdeveloped nations — the initiative-takers, the smart and resourceful self-select for emigration, and take their work ethics and brains abroad. In the early twentieth century and again in the 1950s and 1960s hundreds of thousands of Greeks fled to the diaspora.

While I was traveling I missed this fine story by Niki Kistantonis about the newest generation of Greeks flooding abroad because of the lack of opportunity. For much of its modern history, one of Greece’s most successful exports has been its young. It’s a common story in underdeveloped nations — the initiative-takers, the smart and resourceful self-select for emigration, and take their work ethics and brains abroad. In the early twentieth century and again in the 1950s and 1960s hundreds of thousands of Greeks fled to the diaspora.

Those who remain, especially the ambitious and the well educated, find themselves choked from opportunity. She quotes a recent poll:

According to a survey published last month, seven out of 10 Greek college graduates want to work abroad. Four in 10 are actively seeking jobs abroad or are pursuing further education to gain a foothold in the foreign job market. The survey, conducted by the polling firm Kapa Research for To Vima, a center-left newspaper, questioned 5,442 Greeks ages 22 to 35.

The economic crisis in Greece has taken a huge toll on the country, and heightened generational anxiety. At the same time, economic opportunities are dampened everywhere right now, not just in Greece.

I just spent 10 days in Lebanon, long famed as the most debt-ridden nation in the world. It was striking during this visit to regularly have people ask me whether Greece has surpassed Lebanon in debt. Even one Greek banker I met had to stop and calculate in his head before concluding that Greece was barely ahead of Lebanon in debt-to-GDP ratio.

Greece and Lebanon have painful similarities: impressive human capital, speedy journeys from developing to developed economies, endemic graft, ossified political structures, and diasporas whose economic achievements dwarf those of the metropolis.

Iran on Israel’s border

For as long as I’ve been covering this region, there have been some Israeli officials who describe Hezbollah as a crack division of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and conclude that Iran has literally surrounded Israel.

In the war of rhetoric and symbols, Iran appears only too happy to oblige.

This weekend I visited “Iran Park” in Maroun Al Ras, the Lebanese border village where one of the first and nastiest engagements of the 2006 war was fought. Israeli ground troops got bogged down for days on the ridge at Maroun, and Hezbollah fighters consider it one of their finer engagements of the war.

The Iranian government has funded and designed a lush park near the site of the battle, on the mountainside directly overlooking Israel. In the parking, visitors can stand at an observation point beside an Iranian flag fluttering in the wind, and look directly down at the Israeli hamlets of Avivim and Yir’on.

The Iranian government has funded and designed a lush park near the site of the battle, on the mountainside directly overlooking Israel. In the parking, visitors can stand at an observation point beside an Iranian flag fluttering in the wind, and look directly down at the Israeli hamlets of Avivim and Yir’on.

Through an arcade of ponsiana trees and an arch, past a commemorative plaque crediting President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad with gifting the park to the Lebanese, visitors find terraced playgrounds and picnic spots refreshed with the mountain breeze.

There’s soft-serve ice-cream trucks, grills, and replica of the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem – naturally, topped with an Iranian flag as well. Presumably, Israelis down in the valley can look up and see the Iranian flags and the replica Jerusalem mosque.

Along the path, detailed placards provided educational information about Iran – its population, its provinces, the neighborhoods of Tehran, and so on.

On Sunday mourning the park was already nearly full by 10 a.m. with families that had come to enjoy the cooler temperatures of Jabal Amal.

Three families from the humid coast had assembled under one of the palm-frond roof picnic stations, setting in for a long day grilling and eating.

“Coffee?” said Jihan Muselmani, 35.

“We come here for the clean air,” said Najua Khanafer, 52. “We thank all those who work for our land. Sayed Hassan, Iran, Qatar.”

“This will be the first place the Israelis destroy during the next war,” said Jihan.

“Even if they destroy it, we will build it up again,” said Rabab Haidar, 28.

“If you won’t have coffee, you must at least try these apples,” Jihan insisted, clutching a plastic tub of tiny green fruit. “They come from our own tree.”

First look at the book

A UPS courier woke me up this morning in Beirut with some pre-publication copies of A Privilege to Die — my first look at the actual book. Odysseas had shown me a copy on g-chat yesterday of “Baba’s book,” but the feeling was complete when I held a physical copy in my hands of this project that has been four years in the making. Here I am on Borzou and Delphine’s balcony in Ashrafieh, outside the borrowed office where I typed up so many of the early notes that fed into the story.

9/11 Memoirs

The ninth anniversary of Sept. 11 passed in New York this weekend with a focus on the two fracases of the day: the “Ground Zero mosque” and the would-be Koran burners and their emulators.

The ninth anniversary of Sept. 11 passed in New York this weekend with a focus on the two fracases of the day: the “Ground Zero mosque” and the would-be Koran burners and their emulators.

For the decade between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the Twin Towers, many Americans turned away from the rest of the world, a regretful sort of superpower powernap. Talking about Sept. 11 is shorthand for talking about how America should exercise its power in the wider world, how to measure blowback, how to balance soft and hard power, how to curb extremism at its roots while also pruning its branches.

Anne and Manny Fernandez wrote a piece yesterday that catalogues what 9/11 looks like today, rather than trying in overwrought prose to figure out what it means. They focus on “an unmistakable sense that a once-unifying day was now replete with division” – although one could argue that from the first decisions that followed the Sept. 11 attacks American political life grew more divided than ever.

In a similar vein, I reviewed Scott Malcomson’s memoir in the Times’ Sunday Book Review section. Reading his recollection of 9/11 and the years that followed forced me for the first time in ages to recall their intensity and the sense of a bottom falling out.

The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, found me on my stoop in Boston’s South End, waiting for a ride to work. One minute I was enjoying the sunshine, worrying about the logistics of moving house. Then the first plane struck the north tower of the World Trade Center and my entire frame of reference lurched. What I don’t quite remember is how that painful, personal moment connected to America’s national experience in the aftermath of the attacks — and to what many saw as the erosion of civil liberties, unnecessary wars and the willingness to scorn allies and international institutions.

It is this link that concerns Scott L. Malcomson in “Generation’s End: A Personal Memoir of American Power After 9/11.” How, Malcomson inquires, did the world’s sole superpower surrender its better judgment and squander so much good will? Read the rest.

Normalcy, perhaps, is a feeling that only prevails in historical retrospect.

Egypt’s military and its next president

In Sunday’s New York Times I wrote about the Egyptian military’s central role in Egyptian society and what position it might take on the selection of President Hosni Mubarak’s successor. So much is opaque in Egypt’s power structure, and nobody outside Mubarak’s inner sanctum has a clear picture of how anything works, precisely. The retired military officers, opposition leaders, defense consultants, officials, and analysts that I interviewed are either expressing the views of an interested party in the case of the officials and politicians, or are cobbling together theories from a sort of reading of the tea leaves.

In Sunday’s New York Times I wrote about the Egyptian military’s central role in Egyptian society and what position it might take on the selection of President Hosni Mubarak’s successor. So much is opaque in Egypt’s power structure, and nobody outside Mubarak’s inner sanctum has a clear picture of how anything works, precisely. The retired military officers, opposition leaders, defense consultants, officials, and analysts that I interviewed are either expressing the views of an interested party in the case of the officials and politicians, or are cobbling together theories from a sort of reading of the tea leaves.

Even those who believe the military could play an important role have few ideas of how, in practice, the military would exercise that role. Possibilities include:

- A military coup, which most people said was unlikely.

- An expanded role in direct rule, for example by moving to completely shut down the Muslim Brotherhood.

- An internal negotiation with potential successors that protects the military’s continued privileged status

- A tense internal negotiation in which the military does not obtain the assurances it wants, and then seeks to undermine the next president.

- A weak successor who faces a public opinion crisis similar to the uproar in Egypt during the 2008-2009 Gaza war, when Mubarak kept the border closed and essentially sided with Israel over Hamas. In that case, one official source speculated, the military might organize a direct or indirect coup if it fears an ineffective president will be unable to keep domestic order in a time of crisis.

Issandr El Amrani, author of the excellent Arabist blog, gave me a very helpful interview for the story and elaborated further on his blog about the succession prospects. It’s worth reading the whole post, but here’s his thesis:

This situation, in a sense, is ideal for the military, confirming its central role and placing senior military officers — since we are probably talking about that rather than the army as a corporate entity — of winning either way: they will be wooed by Gamal (or any other successor) to support him and, if they decide not to, would easily garner popular support for their own candidate. Should they decide to support Gamal Mubarak, they need do nothing but sit back and allow the process concocted for his “legitimate” election to take place. If they decide against it, it will be most likely a decision taken behind the scenes rather than publicly, with the selection of the candidate taking place in collusion with elements of the ruling party rather than, as some have said, by tanks descending into the streets. A soft coup, if you will, if only because the regime as a whole in Egypt has an interest in preserving the myth of constitutional legitimacy — they would bend the rules, rather than break them altogether.

Stephan Roll, a Berlin-based researcher, also wrote about the military and succession at the Carnegie Endowment’s Arab Reform Bulletin (another version of the essay ran in Al Masry Al Youm’s English edition). He sees the military as a fulcrum point between the ruling party’s old guard and new guard.

For the first time in Egypt’s modern history, the business elite are playing a role in the succession question, but it is still not clear whether that role will be decisive. … So far, the military leadership has kept out of the power struggle between old and new guards inside the party and the government. In general, this neutrality seems to serve the interests of the old guard, as a positive signal by important military officers regarding the new guard and Gamal Mubarak would certainly give them a boost.

As with most of the questions about Mubarak’s successor, the most interesting decisions are likely to be made outside of the public eye, and many of them – like the military’s struggle to maintain its position, or like the ruling party’s internal split between two factions of very rich officials – might take several years to play out. The military has received nearly $40 billion from the United States, which prizes the Egyptian military’s stability and Washington-allied positions. The U.S. also appreciates the Egyptian military’s agreement to stay out of regional affairs, concentrating on defending Egypt’s regime and borders.

The military has much to lose in the transition, these officers and analysts say. Over the years, one-man rule eviscerated Egypt’s civilian institutions, creating a vacuum at the highest levels of government that the military willingly filled. “There aren’t any civilian institutions to fall back on,” said Michael Hanna, a fellow at the Century Foundation who has written about the Egyptian military. “It’s an open question how much power the military has, and they might not even know themselves.”

Bahrain’s unfolding crackdown

Since the middle of Ramadan, when I wrote about Bahrain’s sweep of Shia activists, the government has announced charges against 23 alleged coup plotters, saying they were planning to overthrow the government with funding from abroad, mainly Iran.

Since the middle of Ramadan, when I wrote about Bahrain’s sweep of Shia activists, the government has announced charges against 23 alleged coup plotters, saying they were planning to overthrow the government with funding from abroad, mainly Iran.

Bahraini human rights activists continue to protest the government’s detention of hundreds of Shia politicians and activists; on Sept. 11 they began a “sit-in,” pictured here, demanding an end to torture and the release of all those detainees not charged with a crime.

King Khalifa gave an angry speech, saying the years of tolerance and pardons were over, while the government belatedly started making a case to public opinion beyond the Gulf, addressing the allegations of torture and illegal detention while also articulating claims that the Shia political opposition figures it arrested pose an actual threat to the state.

Bahrain’s Ambassador to the U.S., Houda Ezra Ebrahim Nonoo, wrote in her letter to the Times:

Against the backdrop of continuing incidences of violence and public disorder, arrests were made because significant evidence was discovered of a network planning and instigating attacks on public property and inciting violence. … Our commitment to further reform within an open, tolerant Middle East society remains undiminished.

Solid evidence could help that case, but so far the Bahrain case highlights some really interesting regional questions.

- Can the ruling families in the heterogenous Gulf countries find a way to extend minority rights while maintaining stability?

- Are the Shia minorities in Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia seriously interested in taking power, like the Shia in Iraq, or will they be satisfied with a more fair political system?

- Is Iran actively stirring up the Shia in the Gulf countries as a threat to ruling families, or are we seeing nothing more than flow of alms money from religious Shia through their references – usually based in Iran and Iraq – back to the faithful in the Gulf?

- How much rule of law is possible in states were absolute authority is concentrated in the hands of a single, hereditary ruling family?

- What is the Khalifa family trying to accomplish long-term? And what prompted the timing of this wave of arrests: Real information about a prospective coup? Concerns that Shia parties would win a majority in the October parliamentary elections? Real worry that simmering unrest would hurt Bahrain’s ability to win and retain foreign companies?

The Bahraini press has begun to publish some of the government’s answers to these questions. There have been some newspaper columns in the Gulf that express the ruling families’ fear of Iran-backed Shia uprisings, an anxiety that has percolated throughout the peninsula in various forms for centuries.

Steven Sotloff wrote an excellent piece on The Middle East Channel about Bahrain’s Shia crackdown, in which he details a lot of the background in what he describes as conflict not between Shia and Sunni but between the Shia majority and the ruling Khalifa family. Sotloff gives us a lot of useful detail about the government’s housing policy, which favors newly naturalized Sunni immigrants recruited for the security forces over long-time Shia citizens, and other Shia grievances about employment and political rights. His measured tone helps referee a lot of the heated claims about Iranian funding, dual loyalty and sedition.

Brotherhood boycott?

Parliamentary elections are coming up this fall in Egypt, probably in October or November. But the opposition and ruling National Democratic Party alike have their eyes on presidential succession, assuming that President Hosni Mubarak, who is ill and has ruled for 29 years, probably won’t run again in 2011. In that light, the parliamentary elections have become part of the broader political jockeying.

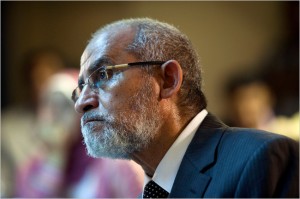

The Muslim Brotherhood commands by far and away the strongest street support among the opposition factions, but it’s a banned society whose parliamentary representatives are technically independents. Meanwhile, the secular opposition parties want to boycott the parliamentary elections to protest the ruling party’s heavy-handed manipulation of the voting process (since the last election, for instance, the government has cancelled the judiciary’s right to oversee polling stations). That’s the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide Mohammed Badie in the picture, getting yelled at by secular opposition leaders during an iftar.

The Brotherhood and the secular National Association for Change are circulating a petition calling on the government to amend the constitution and reform the voting process to allow free and fair elections. It’s a rare instance of the Islamist and secular opposition working together, but even in this arena they’re competing to show who’s stronger. The Brotherhood has collected nearly 700,000 signatures; the National Association for Change only 100,000. You can follow the dueling signature drives on the Brotherhood petition page and the NAC petition page.

You can also read more about the Brotherhood’s internal debate between seeking power and challenging it in my story today in The New York Times.

CAIRO — One by one, the guests at the Muslim Brotherhood’s annual Ramadan iftar banquet strode to the rostrum. A who’s who ofEgypt’s opposition began hectoring the Islamist group. The Brotherhood, they said, by far the most muscular and influential of Egypt’s dissident organizations, should withdraw from the coming parliamentary election that would most certainly be rigged by the authoritarian government.

“Why won’t you take the initiative?” shouted Karima El-Hefnawi, a secular activist and leader of the popular Kifaya protest movement. “Why won’t the Muslim Brotherhood boycott this farce?” The supreme guide of the Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie, sat uncomfortably a few feet to her right.

At the close of the evening, Mr. Badie was noncommittal. The Brotherhood, he said, in time would make up its mind: “Haste makes waste.”

The Muslim Brotherhood is engaged in a delicate dance. Despite all efforts to marginalize the Islamist organization by the United States and its close ally, the Egyptian government, it remains the most credible opposition group. Some of its members want the Brotherhood to fight the government head on, but the Islamist leadership has other goals: freedom to proselytize and organize in neighborhoods, and in the long term, a lifting of the official government ban on its activities.

With an end in sight to President Hosni Mubarak’s 29-year reign, the Brotherhood appears to be signaling its willingness to cut a deal with Mr. Mubarak’s potential successors by not overtly challenging the ruling party’s monopoly on power.

PTD in Albuquerque

I’ll be in Albuquerque on Oct. 24 talking about Hezbollah and A Privilege to Die. Diane Schmidt published an interview with me in the Albuquerque Examiner.