Revolutionary Times

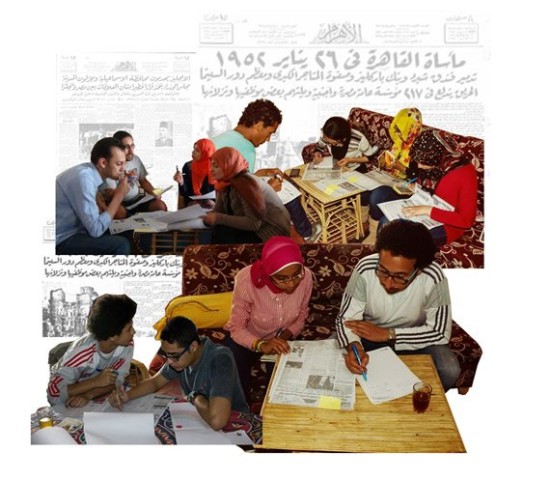

Photos: Youmna El-Khattam/Collage: by Nermine El-Sherif

[Published in the Carnegie Reporter. Preview available on Carnegie Corporation website.]

Research on the edge

Even in the early days of Syria’s uprising, it was nearly impossible to do independent research. From early on in the rule of President Bashar al-Assad, which began in 2000, very little leeway was allowed for any work that might challenge the regime. Academics, journalists, political activists, even humanitarian workers were subject to harsh measures of control. The situation worsened after peaceful protests erupted across the country in 2011. Nonviolent activists were imprisoned, exiled, or killed, and armed insurgents took their place. From the start, the conflict restricted movement around the country. Even worse, authorities on the government side and later among rebels wanted to manipulate any research or reporting from their tenuous zones of control. Analysts began to call Syria a “black box,” an unruly place off-limits to credible researchers.

Into this confusion stepped two Syrian-born academics: Omar Dahi, an economist at Hampshire College, and Yasser Munif, a sociologist at Emerson College. They practiced traditional disciplines at reputable research institutions, but they wanted to conduct unconventional research. How were Syrians adapting to the transformation of their society and the disintegration of an old order? Dahi and Munif wanted to bring systematic rigor to studying the experiences of the thousands, eventually millions, of Syrians who were building new modes of self-governance, beyond Assad’s control, or who were adapting to new lives and identities in the maelstrom of exile. They believed they could conduct meaningful social science in the “black box.”

“Most of the research about Syria revolved around geopolitical conflict and strategies, interested in a top-down perspective,” Munif said. “I was interested in the other way around. I wanted to understand participatory democracy, the different ways people were conducting politics after the collapse of the state.”

Like other radical developments that accompanied the Arab uprisings and government backlash, Syria’s crisis demanded sustained scholarly attention. And research in a rapidly evolving war zone, in turn, required support from a flexible and imaginative institution. Dahi and Munif found their backer in the Arab Council for the Social Sciences, a quietly transformative venture that’s been midwifing a network of Arab scholars to more confidently practice a new brand of social science that rises directly from the concerns of a region in turmoil.

Dahi and Munif applied in the fall of 2012 for the first batch of funding offered by the grantmaking organization, known by its acronym, the ACSS. Dahi wanted to study the survival strategies of refugees. By the time his grant had been approved and he began research, the number of refugees had swollen from a few hundred thousand to nearly two million. He partnered with researchers and activists in the region who were devoting much of their time to the urgent needs of resettling refugees and defending their rights. Munif wanted to study the way local people took charge of their own lives and governed themselves. He chose a provincial city called Manbij, in northeastern Syria. By the time he began his field research, government troops had been driven from the city, leaving it in the hands of local civil society groups and rebels.

By 2014, Munif had to interrupt his own work prematurely when Islamic State rebels conquered Manbij. “Without the ACSS, I wouldn’t have been able to do this type of work. They funded the entire project from A to Z,” Munif said. “ACSS is willing to experiment with new types of research, new methodology. With the Arab revolts they are funding some interesting projects that would not get funding from traditional sources.”

Arab social science

It’s worth pausing for a minute to look at the research that came out of Munif and Dahi’s loose collaboration, because it conveys a sense of what a different kind of social science looks like—in the terms of ACSS, a “new paradigm” that addresses questions of concern to people who live in the Middle East and North Africa.

In his work among Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan, Dahi identified ways that humanitarian aid manipulated the politics of the refugees, in some cases fostering deeper sectarian division, and in others strengthening a more inclusive kind of citizenship. At the same time, Dahi helped to build an online portal that will serve as a data resource for other scholars. He found many willing collaborators within the active community of regional researchers, advocates, and activists. Munif has already published extensively on the local governance and decision-making structures he discovered in Manbij, and he’s currently working on a book that counters “the dominant narrative about Syria,” which in his view “reduces the Syrian uprising to violence, chaos, and nihilism.”

This project is but one of dozens supported by the ACSS since it set up shop in 2010 with a tiny staff but grand ambitions to foment change in intellectual life in the Arab world. Formally, the Arab Council incorporated in October 2010 but only hired staff and began operations from its Beirut headquarters in August 2012. The experiment is still young, but after two major conferences to present research, two business meetings of its general assembly, and the third cycle of grants underway, ACSS is moving from its organizational infancy into adolescence.

Still, some might see its mission as exceedingly quixotic: to foster a standing network of engaged activist intellectuals who set a critical agenda and use the best tools of social science to address burning contemporary questions. And all this ambition comes against the backdrop of a region governed by despots for whom academic freedom is in the best cases a low priority, and in the worst, anathema. “We’re enabling conversations that hadn’t taken place,” said Seteney Shami, the founding director of the ACSS. “It’s too soon to say how we’ve affected social science production, but we have created new spaces. I think we have made a difference.”

The method is as straightforward as the idea is bold. Solicit proposals, especially from researchers who aren’t already part of well-funded and established networks, or who are working on different questions than the mainstream Western academy, which still dominates the research landscape. Invite researchers (ACSS-funded or not) from the region to join the ACSS as voting members who ultimately control its policies and agenda. See what happens.

Since doling out its first grants in 2013, the ACSS has awarded $1.162 million to 108 people. Its annual budget has grown from $800,000 in 2012 to close to $3 million in 2015. The first round of research has been completed, and voting members of the Council’s general assembly this year elected a new board of trustees. (There are 58 voting members out of a total of 137 in the general assembly, according to Shami.) It’s been a dizzying journey for a small organization that supports a type of research criminalized throughout much of the region.

The founders and original funders were determined to promote regional scholarship. Carnegie Corporation in particular has aimed much of its funding in the region toward local scholars, with the intention of stimulating and enabling local knowledge production. The Arab Council complements a number of other efforts in the region to strengthen research and social science. New universities, think tanks, and research centers are emerging in the Arabian Peninsula. Arab and Western academics have formed partnerships, sometimes individually and sometimes at the level of academic departments or entire universities. The magnitude of the ACSS’s impact will only become clear in the context of a wide web of related ventures—all of them taking shape at a time of enormous change and pressure.

All across the Middle East and North Africa, academic researchers face daunting obstacles. There are bright spots, like the active intellectual communities in the universities in Morocco and Algeria. But some of the oldest intellectual centers, like Egypt, struggle under aggressive security and police forces as well as university leaders whose top concern is to ferret out political dissent. War has disrupted intellectual life in places like Syria and Iraq. Government money has poured into the education sector in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, but the lack of academic freedom has dulled its luster.

“The Council was conceived at a time when repression was high but the red lines were clear,” Shami said, referring to the years before the uprisings, when the ACSS was in its planning phase. The current logistical challenges underscore the difficulty of the changing conditions for researchers in the Arab region. An organization dedicated to free inquiry, the ACSS chose to incorporate in Lebanon, where it could operate without governmental restrictions and draw on a vibrant local academic community. Even that location is an imperfect choice.

Members from Egypt, for example, now face new restrictions when they want to visit Lebanon. So far it’s not impossible for Arab scholars to travel around the region, but it’s getting harder. Lebanon’s excessive red tape has thrown up numerous hurdles. For example, the ACSS is currently seeking special permission from the government of Lebanon to allow its international members to vote online on internal policy questions. Equally important, according to Shami, is that work permits for non-Lebanese people are becoming more difficult to obtain, which makes it challenging for the ACSS to hire staff from different parts of the region.

Many resources other regions take for granted don’t exist in the Arab region, where governments restrict access to even the most mundane archives. Data about everything from the economy to food production to the population is treated as a state secret. Permits are difficult to secure. Until the ACSS compiled one, there wasn’t even a comprehensive list of the existing universities in the region. It was these challenges that the founders of the ACSS had in mind, but by the time the organization incorporated in borrowed space in Beirut, the ground had begun to shift. Tunisia’s popular uprising in December 2010 began years of political upheaval across the region. The horizons of possibility briefly opened up, until the old repressive regimes returned in full force almost everywhere except Tunisia.

“We started off at a moment of heightened expectations about the role social sciences could play in the public sphere,” Shami said. “Now we’re in a situation that is far worse in every possible way. These are all big shocks for a young institution. But so far, so good. People are saying it’s impossible to work, but the evidence is that they’re still producing.”

Everything all at once

The ACSS put a lot of balls into the air from the start. Its founders wanted to create a standing network for scholars from the region and who work in the region. Their goal was to empower new voices, connect them with established academics, and nurture the relationships over a long term. That way, even scholars at out-of-the-way institutions, or smaller countries traditionally ignored by the global academic elite, might get a hearing. The Council also wanted to integrate Balkanized research communities, bringing together scholars who often published and collaborated exclusively in Arabic, English, or French.

Other long-term goals factor into the project’s design. Some of the grant categories, like the working groups and research grants, explicitly aim to change the discourse in academic social science. Others, like the “new paradigms factory,” intend to bring activists and public intellectuals into conversation with academics. The ACSS is a membership organization; each grantee can choose to become a permanent member with voting privileges—a sort of institutional democracy and accountability in action that the Council hopes will filter into other institutions in the region.

Finally, this summer (2015) the Council will publish its first in-house work, the Arab Social Science Report, a comprehensive survey of the existing institutions teaching and doing research in the social sciences in the region. The ACSS has established theArab Social Science Monitor as a permanent observatory of research and training in the region and hopes to produce a new report on a different theme every two years, in keeping with its role as a custodian as well as mentor of the Arab social science community.

The inaugural survey demanded an unexpected amount of sleuthing, said Mohammed A. Bamyeh, the University of Pittsburgh sociologist who was the lead author on the report and helped oversee the team that produced it. In some cases it was impossible to obtain basic data such as the number of faculty at a university or their salaries. “If you call them, they will never tell you,” Bamyeh said. “For some reason, it’s a secret.”

In the end, however, a year’s worth of legwork produced a surprisingly thorough snapshot of social science in the region. Researchers identified many more academics and other researchers than they expected, and a wider range of periodicals and institutions. Freedom of research turned out to be a better predictor of quality than funding did, Bamyeh said. The quality varied widely, but Bamyeh said social science in the region is “mushrooming.” We may not have appreciated this growth because we don’t have an Arab social science community,” he said. “We have a lot of individuals doing individual research but they are not connected to each other.”

Sari Hanafi, a sociologist at the American University of Beirut, has studied knowledge production in the Arab world and is intimately familiar with the paucity of quality peer-reviewed journals, professional associations, and the unseen scaffolding that supports top-notch research. He was one of the founding members of the ACSS and currently sits on its board, but he is pointed about the bitter challenges impeding research in the region.

“Social science in the Arab world is in crisis,” Hanafi said. “Social sciences are totally delegitimized in the Arab world.” Repressive states wanted only intellectuals they could control, he maintains, so they starved institutions that could produce the large-scale research teams required for any serious, sustained research. The problem has been compounded, Hanafi said, by ideologues and clerics who want to fulfill the role that social science should rightfully play: providing data, assessing policy options, and generating dissent and criticism.

Quality research anywhere in the world depends on money, intellectual resources, and the support of society and the state, according to Hanafi. “In the Arab world, this pact is still very fragile,” he said. “You don’t have a strong trust in the virtue of science.” He hopes that the ACSS can play a part in a wider revival, in which social scientists reclaim their influence and beat back the encroachment from clerics and authoritarian states. “The mission and vocation of social science in this region is to connect itself to society and to decision makers,” Hanafi said. He believes the Arab world needs stronger institutions of its own, including independent universities, governments sincerely committed to funding independent research, and professional associations for researchers. Efforts like the Arab Council can help pave the way.

Participants at the ACSS conferences are encouraged to present and publish in Arabic. The Council also emphasizes the value of its members as a collective network. Pascale Ghazaleh, a historian at the American University of Cairo, said it was “mindblowing” to meet scholars she’d never heard from around the region at the the ACSS annual meeting in Beirut in March 2015. She said she was moved to hear her colleagues discussing their work in their own language. “It was the first time that I’d been surrounded by people who were unselfconsciously using social science terminology in Arabic,” Ghazaleh said. “It’s something to be proud of.”

The language is part of an intentional long-term strategy to anchor the Council and its social science agenda in the region. Although many of its founders have at least one foot in a Western institution, Shami said that “we see ourselves as fully homegrown and firmly based in the region but interacting with the diaspora as well.” The majority of the trustees, for instance, are based in Arab countries.

“It is an ongoing conversation as to who decides the main questions of research for social sciences,” Bamyeh said. “Can there be something like an indigenous social science that has its own methods? It is essential for social sciences in the Arab world to develop a strong sense of their own identity.” As an example he cites an Egyptian sociologist in the 1960s who discovered at the post office a bag of unaddressed letters, most of them containing prayers and pleas for help from the poor written to a popular folk saint. A clerk was about to throw them away. The sociologist took them home and produced a seminal study of Egyptian attitudes and mentality.

That’s the sort of approach that Bamyeh said he hoped to see employed after the Arab revolts. Instead, he was disappointed to find many American sociologists trying to apply existing Western models to the cases of Egypt and Tunisia. “It was an opportunity to acquire new knowledge,” Bamyeh said. “We need an independent Arab social science that feels its own right to ask questions, questions not asked by the European and American academy. It’s not nationalistic, although it might sound that way. It’s really a question of a scientific approach that comes out of a local embeddedness.”

Activist research

The architects of the ACSS have embraced that quest, encouraging research that springs from local problems, and supporting work from outsiders and nonacademics. In Beirut, the ACSS supported an atypical multidisciplinary research team that explored the misuse of public space and the confiscation of people’s homes. As a result of that research project, Abir Saksouk, an architect and urban planner without an institutional home of her own, launched an ongoing public campaign to save the last major tract of undeveloped coastline in Beirut.

Today she is spearheading one of the most dynamic and visible grassroots social initiatives in Lebanon: the Civil Campaign to Protect the Dalieh of Raouche. The Dalieh is the name of the grassy spit of rock that flanks Beirut’s iconic pigeon rocks. Cliff divers used to perform death-defying Acapulco-style style leaps from the Dalieh’s cliffs until last year, when developers suddenly fenced off the last publicly accessible green open space in Beirut. The campaign that Saksouk helped initiate wants to stop the Dalieh from being transformed into a high-end entertainment and residential complex.

“ACSS was a huge push forward,” Saksouk said. It wasn’t the money, she said, so much as the people with whom it connected her. She was mentored by academics, given a platform to publish in Arabic, and introduced to other people thinking about ways to engage with their city. “My activism on the ground informed what I wanted to focus on in my research, and the paper I wrote for the ACSS informed my activism,” Saksouk said.

The Civil Campaign has started a contest, soliciting alternative, public-minded proposals for the Dalieh peninsula. The point, Saksouk said, is to energize a social movement and change the way Beirutis think about their city’s public space. Her research collaborator, Nadine Bekdache, studied the history of evictions, and together the pair explored the concepts of public space and private property. These are theoretical concepts with explosive implications, especially in a place like Beirut where a few powerful families dominate the government as well as the economy.

“A lot of people are sympathetic but don’t think they can change anything,” Saksouk said. “We’re accumulating experiences and knowledge. All this will lead to change.”

Egypt: In the shadows of a police state

In contrast, the clock has turned backward on the prospects for reform and innovation in Egypt, long considered a center of gravity for Arab intellectual life. Egypt has some of the region’s oldest and biggest universities, and historically has generated some of the most important thinking and research in the Arab world. But Egypt’s academy has suffered a long, slow decline as successive dictatorships suppressed academic life, fearing it would breed political dissent.

In the two-year period of openness that began after Hosni Mubarak was toppled in 2011, university faculty members won the right to elect their own deans and expel secret police from their position of dominance inside research institutions. Creative research projects proliferated. The ACSS was just one of many players during what turned out to be a short renaissance. A May 2015 U.S. State Department report on Egypt’s political situation found “a series of executive initiatives, new laws, and judicial actions severely restrict freedom of expression and the press, freedom of association, freedom of peaceful assembly, and due process.”

At least one well-known the ACSS grant winner, the public intellectual and blogging pioneer Alaa Abdel Fattah, languishes in jail; he was detained before he could complete the paperwork to start his research. Officials even took away his access to pen, paper, and books after his prison letters won a wide following.

Universities have seen a severe decline in academic freedom and some researchers have stopped working or have fled. Outspoken academics like Khaled Fahmy, a historian who has been a critic of military rule and also a spokesman for freer archival access, are waiting out the current turmoil abroad. Political scientist Emad Shahin (who left Egypt and now teaches at Georgetown University) was sentenced to death along with more than a hundred others in May 2015 in a show trial. Some Egypt-based researchers have left since 2013, many grantees remain. The ACSS continues to receive applications from Egypt, and has become all the more vital to that country’s scholars.

Cairo native and historian Alia Mossallam used her research grant to hold an open workshop about writing revolutionary history. As protests roiled the capital, Mossallam quietly organized a workshop that drew 20 people, some from the academic world, some activists, and some professionals and workers who were intrigued by her proposal to study the historiography of “people who are written out of histories of social movements and revolutions.”

Tucked away on an island in the Nile in Upper Egypt, Mossallam’s workshop brought professional historians together with amateur participants. They studied the history of Egyptian folk music and architecture, they looked at archives and newspaper clippings, and then the students used their new skills to produce historical research of their own. Mossallam carefully avoided politics in her open call for workshop participants, but any inquiry into the history of revolution and social movements at Egypt’s present juncture is by nature risky.

Contemporary politics might be a third rail, but in her workshop the Egyptian participants could talk openly about past events like the uprising and burning of Cairo in 1952, or the displacement of Nubians to build the Aswan High Dam. At a time when political speech has been banned, history offers a safer way to talk about revolution. “These workshops are a search for a new language to describe the past as well as the present,” Mossallam said. “Watch out for how you’re being narrated. A lot of the things the participants wrote engaged with that fear, the struggle to maintain a critical consciousness of a revolution while it’s happening.”

Her project wouldn’t have been possible without the Arab Council’s forbearance. The Council encouraged her to find creative ways to engage as wide an audience as possible and gave her extra time to recalibrate her project as conditions in Egypt changed. No other Arab body gives comparable support to Arab scholars, Mossallam said. “They ask, are we asking questions that really matter?” she said. “Are we trying to reach a wider public?”

Can it last?

Sustainability remains an open question. Although the ACSS is registered as a foreign, regional association under Lebanese law and considers itself a regional entity, the organization currently depends on four funders from outside the Arab world for its budget: Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Ford Foundation, the International Development Research Centre of Canada, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. If at some point in the future those funders turn their attention elsewhere, the ACSS, for all its promise, could quickly reach a dead end. According to Shami, “It’s as sustainable as any other NGO that depends on grants.”

While it’s politically tricky for an Arab institution to take Western money, funds from various regional sources can come with strings attached. Ideally, Shami said, the ACSS would like to find acceptable funding sources from within the region.

The Arab Council’s accelerated launch has attracted wide interest, creating new challenges as the organization matures. “We’ve built up a lot of expectations. People think we have unlimited resources,” Shami said. “We might be coming up against hard times. We might be starting to disappoint people.” Just as important as money is the political structure of the region. Lebanon, Tunisia, and Morocco remain the only relatively free operating environments for intellectual work in the region, and that freedom is always under threat from militant movements, authoritarian parties, and regional wars.

Deana Arsenian, Carnegie’s vice president for international programs, attended the March 2015 meeting and was impressed by the enthusiasm of the several hundred participants, whose optimism for research far exceeded their expectations for their region’s political future. “The act of creating a network across multiple countries is in and of itself a major feat, given the realities of the region,” Arsenian said. “While it’s a work in progress and many aspects of the association have to be worked out, the interest among the members in making it succeed seems very strong.”

ACSS came at a moment of great change and opening in the Middle East, and was rooted in a region that needs to be heard from. From the beginning the ACSS has intentionally included all those who reside in the Arab region regardless of ethnic or linguistic origins, as well as those in the diaspora. As it moves past the startup phase, the Arab Council’s scholars will have to decide whether their aim is to increase the visibility in the wider world of scholars of the region, or whether it’s to create a parallel universe. It will also have to grapple with its definition: what is an “Arab” council? Shami herself is of Circassian origin, and there are plenty of other non-Arab ethnicities and language groups in the region: Kurds, Berbers, and so on. Many of the early success stories in the ACSS are geographical hybrids, trained by or based at Western institutions, which she points out reflects the global hierarchies of knowledge production.

The Council might also have to refine the scope of work it supports. So far, in the interest of transparency and interdisciplinary research, the ACSS has been very flexible and open to all communities of scholars, knowing that as a result the work of its grantees will be uneven. Another question is whether, once the novelty wears off, the ACSS conference will become a genuine source of scholarly prestige for social scientists. Its second annual conference, in March of this year, attracted four applicants for every presentation slot. Almost nobody who was invited to present dropped out.

Arab Council has already identified a greater breadth of existing scholarship in the region than its founders expected. Over time, it will gauge the quality and rigor of that work. “It’s too early to see the dividends or the fruits, because these fruits depend on how social science is professionalized or institutionalized,” Hanafi said.

Dahi, the economist from Hampshire College who researched Syrian refugees, has stayed involved with the ACSS, helping to organize its second conference this year. Regional research has grown harder, he said, because of the “climate of fear” in places like Egypt and the impossibility of doing any research at all today in most of Syria, Iraq, and Libya. “The carpet is shifting under our feet in ways that academics don’t like,” Dahi said. “Academics like a stable subject to study.”

He believes the Council will face a major test over the next years as it shifts from dispersing grants to pursuing its own research agenda, like other research councils around the world. “The key challenge will be this next step, because you need to create this tradition of quality production of knowledge,” Dahi said. “I’m optimistic. Supply creates its own demand. I don’t believe that in economics, but I do believe it in knowledge production.”

The Arab Spring was a revolution of the hungry

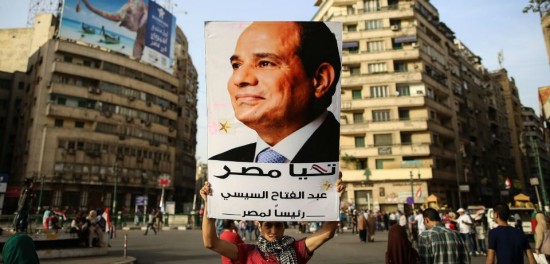

Photo: KHALED DESOUKI/AFP/GETTY IMAGES/FILE

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

The Arab world can’t feed itself, and that’s how the region’s dictators like it.

“The only thing we really need to worry about is a revolution of the hungry,” said one, a retired Air Force general. “That would be the end of us.”

As it turned out, it took less than four years for Egypt’s dictatorship to reconstitute itself, crushing the hope for real change among the people. In no small part, the regime’s resilience was due to its firm grasp of bread politics. The ruler who controls the main staples of life — bread and fuel — often controls everything else, too.

Nonetheless, the specter of a “revolution of the hungry” still worries authoritarian rulers today, in Egypt and throughout the Arab world. Roughly put, the idea is shorthand for an uprising that brings together not only the traditional cast of political and religious dissidents but also pits a far greater number of poor, uneducated, and apolitical citizens against the state.

Look across the region, and regimes have good reason to be afraid. Even in countries where obesity is widespread, people suffer from low-quality medical care and malnutrition due to a lack of healthy food.

The basic equation is stark: The Arab world cannot feed itself. Rulers obsessed with security have created a twisted web of importers and bakeries whose aim is not to feed the population efficiently or nutritiously but simply to maintain the regime and stave off that much feared revolution of the hungry. Vast subsidies eat up the lion’s share of national budgets.

So far, the bakeries haven’t run out of loaves in two of the region’s biggest bread battlegrounds, Egypt and Syria. But the sense of plenty is only an illusion. Food is expensive, people are poor, and repressive regimes rely on imported wheat financed through foreign aid. It’s an unsustainable and volatile cocktail.

“You have a system where access to food is a primary mechanism of social control,” said journalist Annia Ciezadlo, author of the book “Day of Honey,” who has written extensively about food subsidies, unrest, and the use of food as a weapon in the Middle East. “The moment something happens to that supply of subsidized food, everything can go out of control.”

THE ARAB UPRISINGS of 2010 and 2011 offered only the most recent glimpse of what it would look like if people got hit where it hurts the most: at the dinner table.

In 1977, President Anwar Sadat of Egypt managed a feat that had been considered impossible when he broke with the entire Arab world and initiated a peace process with Israel, even traveling to Jerusalem to address the Knesset. The bread conundrum, on the other hand, proved much more intractable.

Sadat tried in January 1977 to cancel Egypt’s expensive wheat subsidy at the urging of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Riots swept nearly every major city, and in two days Sadat caved. He restored the bread subsidy that has remained in place ever since, and the Egyptian military took control of many crucial bakeries to ensure that the government could control the bread supply in a crisis. That awkward status quo prevails to this day. The government’s bread economy is inefficient, unstable, and nearly entirely dependent on foreign imports. But any attempt to tinker with bread prices or subsidies still terrifies the country’s rulers and enrages its citizens.

Regimes took heed. Hafez al-Assad, the dictator of Syria, extolled peasants in his rhetoric and made food independence a central pillar of his regime. For decades, Syrian officials constantly bragged they didn’t need to import wheat.

Dictators in the Arab world learned that one of the best routes to dominance runs through the bakery. Rulers the world round usually deploy some variant of pocketbook politics, rewarding their loyalists with perks like community centers, jobs, and payola — and punishing opposition areas by scrimping on their basic services like roads and schools. In many Middle Eastern countries, the level of control was more basic: Without the government, citizens would starve.

The brittle, undemocratic regimes had, however, no mechanism of oversight and little resilience to withstand outside shocks. So distant events like a bad crop on the Black Sea or low rainfall in Canada could quickly translate into a political crisis in the Levant or North Africa. In 2008, world food prices spiked, and, once again, bread riots broke out across the Middle East. Regimes scrambled to cover the shortfall with handouts and subsidies, on the assumption that their populations might tolerate repression but not hunger.

Indeed, rising commodity prices were one of the triggers in the 2010 to 2011 uprisings. Protesters in Tunisia brandished baguettes. In Egypt, many of the revolutionary chants talked about food, and a central demand was for “bread, freedom, social justice” (it rhymes in Arabic).

The first Syrians to rise up against Bashar Assad included many poor farmers who had been displaced by drought and the government’s neoliberal disinvestment from agriculture. Caitlin Werrell and Francesco Femia at the Center for Climate and Security in Washington, D.C., argue that a series of droughts in Syria from 2006 to 2010 created the preconditions for the uprisings — crop failures drove farmers off their land and raised the level of desperation until Syrians directly challenged their ruler.

Saudi Arabia’s ultrarich monarchy calculated that it could survive any challenge from political dissidents critical of the country’s lack of rights and freedoms — as long as it could keep its citizens in material comfort. The king quickly increased handouts to citizens, and after a brief rumble, Saudi Arabians sat out the regional wave of protests that swept through nearly every other Arab state.

Yet the obsession with food sovereignty and security remains close to the region’s despots. Saudi Arabia has purchased land in fertile water-rich countries like Ethiopia in order to secure its food supply.

In Syria, unscrupulous combatants on all sides have made food one of the war’s central battlegrounds. The regime blocks delivery of food aid to rebellious regions; its blockade of the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus has also kept out truckloads of UN food aid, causing years of famine in the camp. Further afield, the regime routinely bombs bakeries in areas that fall under rebel control, in a method colloquially referred to as “starve-or-surrender.”

The Islamic State, for its part, has made control of the food supply a basic part of its blueprint for power, starting with the bakeries and wheat warehouses, and even facilitating the international aid deliveries that have kept some parts of northern Syria from suffering the same fate as Yarmouk.

THE ARAB STATES are the world’s largest net importers of grains, depending on exports from water-rich North America, Europe, and Central Asia.

So it follows that bread riots will break out every time there’s a disruption in the global food supply. Anger will bubble up every time there’s a drought. Or when oil profits fall and it becomes harder to pay for grain imports. The Middle East North Africa region consumes about 44 percent of global net grain imports, according to Eckart Woertz, author of “Oil for Food: The Global Food Crisis and the Middle East”: “Self sufficiency is not an option in the region,” he said in an interview.

Still, most scholars now accept the idea first proposed by the economist Amartya Sen, that food shortages and famines are usually caused by political mismanagement, not by an actual lack of food.

In the Middle East, that means conditions are still ripe for a tempest. “At the end of the day, we can explain the crisis in terms of political economy: corruption, crony networks favored over rural populations. Droughts don’t cause civil war in Los Angeles,” said Woertz, who studies food and security at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs, a think tank.

And it can’t be ignored that droughts have been a fact of life in the arid Arab world as long as there has been agriculture, and bread riots on their own have yet to transform a dictatorship into a democracy. That’s because the problem is much larger: People in the Arab world have been kept poorer than they should be by corrupt repressive governments that hog national wealth for a tiny elite. Until that changes, hunger and food insecurity will remain yet another symptom of the region’s terrible governance.

A Plan for Syria

Issue brief for The Century Foundation. Download as pdf.

With the Iran nuclear negotiations concluded, attention ought to shift to a political solution for the troubling war in Syria, which has killed about a quarter-million people (estimates range from 230,000 to 320,0001), while displacing 4 million refugees into the Levant and Turkey.2

The United States remains an indispensable source of influence in the Middle East—when it chooses to get involved. It can shift the dynamics of the Syrian civil war by taking two steps. First, Washington should pour a new, higher level of support into the northern front of the civil war, in coordination with key allies, including Turkey and Saudi Arabia. Second, it should continue to promote an end to the war through political negotiations that include all the key domestic and international actors in the conflict and exclude only the most extreme jihadist rebels.

A sustained intervention through proxies on Syria’s northern front would be a messy and inconclusive affair, but if carefully tailored, with pragmatic expectations, it could completely shift the political horizon for the Syrian civil war. No foreign intervention can create an idealistic group of democratic, secular rebels ready to take over the entire country of Syria and replace the regime. With international support, however, it is possible to create a coalition of nationalist rebels capable of making gains against both the regime in Damascus and jihadist extremists, including ISIS, the Nusra Front, and Ahrar al-Sham. An invigorated nationalist opposition could provide the final incentive needed to bring Syria’s combatants into a productive negotiating process.

The conflict is newly ripe for a diplomatic resolution, requiring only a catalyst. Russia, focused on the Ukraine crisis, would entertain an end to the war that preserved its status quo security interests in the Levant. The political and economic windfall from the nuclear deal in Vienna could prompt Iran to increase its aggressive involvement in Syria,3 but it might simultaneously make Iran more open to discussions of a settlement.4 An insecure and aggrieved Saudi Arabia will need to be wooed, as its leaders are irritated by the prospect of a U.S.-Iran rapprochement.5 Yet, the rise of entrenched jihadis and the civilian bloodletting in Syria is equally troubling for the Saudis.6 Turkey is increasingly facing the risk of a spillover effect from the conflict in Syria, and would benefit from a calming of the crisis along its borders.7

All these factors suggest that a well-designed U.S. initiative, coupled with a concerted push to shift the military balance of power on the northern front, could trigger a genuine effort to negotiate an end to the war in Syria.

Existing Intervention: A Sorry Mess

Currently, the Damascus regime and its Iranian backers have encountered little resistance to their maximalist, often criminal tactics. The regime appears to continue to use chemical weapons with little consequence.8 Its armed forces and semiofficial militias have massacred tens of thousands of civilians by dropping barrel bombs, naval mines, and other indiscriminate explosives on neighborhoods under rebel control.9 Yet, the international community has raised no meaningful objections.

American involvement in Syria has been desultory. More than a year ago, when the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Shām (ISIS) expanded its dominion in Syria and Iraq and captured the city of Mosul, Washington vowed to do something; it would no longer consider the war in Syria a strategically inconsequential problem that could be ignored. But a year later, the United States has lagged on its promise to train and equip Syrian rebels. The latest venture, approved a year ago with a $500 million budget, just sent its first class of recruits into the field in July—a paltry contingent of sixty.10 The Pentagon is hamstrung by its obsession with vetting fighters, and its standards are so impractical and unrealistic that they disqualify most credible commanders. The train-and-equip program is further hampered by the insistence that its graduates only fight Islamist jihadists rather than the regime in Damascus.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has not even decided what kind of support to give to the soldiers it has dispatched into northern Syria under the latest iteration of train-and-equip. “I think we have some obligations to them once they are inserted in the field,” Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter told a congressional committee. “They know that we will provide support to them.” But he could not specify what that support would entail: “We have not told them yet,” Carter said the week the newly trained fighters were deployed.11

The U.S. air campaign against ISIS has struck limited targets. With few trusted local proxies on the ground, the U.S. Air Force can have only minimal impact. For now, the only local proxy with fighters on the ground that can regularly ask for U.S. air strikes is the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG).12 The YPG has successfully taken some territory from ISIS, but is anathema to Turkey. Whenever the YPG is too successful, as in June when it captured the border crossing of Tal Abyad between Turkey and Syria,13 the Turks become alarmed and resentful. Ankara considers the YPG as indistinguishable from the PKK, militant Kurdish separatists who have waged an on-again off-again violent campaign in Turkey. The Turkish government will never support an anti-ISIS or anti-Assad campaign dominated by the YPG Kurds.

Meanwhile, as U.S. efforts have floundered, ISIS continues to deepen its state structures, military capacity, and territorial control, and it looks more like an established entity with each passing day.14

With all this bad news and so many unreliable partners on the ground, it’s no wonder that President Obama has kept his distance. Rebels willing to do business with the CIA, DOD and other government agencies have proven a mixed bag. In 2014, for instance, the United States invested considerable resources in Jamal Maarouf’s secular nationalist Syria Revolutionaries’ Front (SRF), which then took control of much of Idlib province. U.S. involvement initially was viewed as a success; a modest amount of money, along with anti-tank missiles, had shifted the battle in favor of “moderate” rebels. In practice, the rebels proved not so moderate, and the success was short lived. The SRF’s governance of Idlib was capricious and riddled with corruption. Civilians in Idlib came to resent the inconsistency and predatory abuses of their liberators. The province suffered punishing regime air strikes, as do all areas liberated by rebels. Eventually, Islamists took over the province and roundly defeated the SRF, which then collapsed.15

Today, the liberated areas of Idlib province are controlled mostly by the Nusra Front (Syria’s Al Qaeda affiliate), and Ahrar el-Sham, a jihadi group that has won plaudits for being more homegrown and nationalist than ISIS and Nusra, but which in practice shares their extreme views, which are incompatible with a pluralistic or secular state. The areas of Idlib province controlled by secular nationalists under the banner of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) survive as timid oases of relative moderation. FSA commanders interviewed in Reyhanli said they do not even try to control local governance, the economy, or social services (as Islamist militias do in their domains), and they admit that they must surrender some share of their resources and weapons to the Islamists who control the FSA’s access to Idlib. They rely on the black market for fuel, sometimes indirectly buying the diesel for their tanks and vehicles from ISIS.

Willing Partners

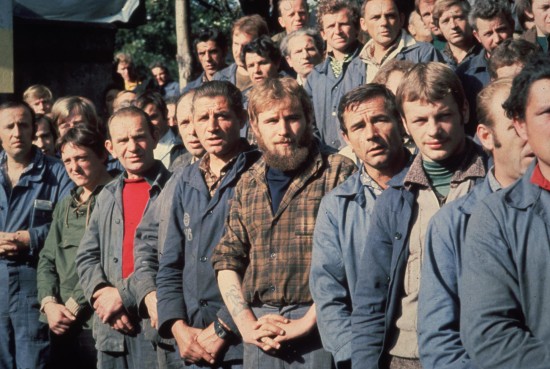

The good news is that there are still plenty of commanders willing to fight under the banner of the FSA, do business with the United States, and espouse political principles and talking points that make them palatable to mainstream Syrians. A recent visit to the Turkish-Syrian border showed a growing group of commanders who control boots on the ground, have a nationalist, rather than Islamist style, and have demonstrated an ability to learn politically.

“At the end we will support any government that gives all Syrians their rights,” Colonel Fares Bayyoush, an army defector who commands an FSA brigade in Idlib province, said in an interview at his headquarters in the Turkish border town of Reyhanli. “From our side, we are going to behave like Syrians. . .If we in the FSA get power, we will protect coexistence.” Half a dozen FSA commanders interviewed in Reyhanli and Gaziantep voiced the same refrain: they want a resolution to the Syrian war that protects all sects and ethnicities, and they want to eliminate the jihadist groups while reintegrating their supporters into society. They have demonstrated a history of coordinating military operations with Kurds and with Islamist fighters. They express a willingness to negotiate with elements of the regime, and they claim to include Christians, Druze and Alawites among the ranks of their fighters.

Much of this sentiment is probably tailored for Western consumption, but it also marks a considerable shift compared to a year ago. Interviews in the same border towns with the same groups in the summer of 2014 had revealed a propensity for grandstanding, Sunni triumphalism, and petulant demands that the U.S. military intervene directly and win the war for the opposition. Today, the same commanders have learned a new political language. The rhetoric of rights and national unity in the hands of pragmatic fighters signals the beginnings of a national accord that could lead Syria out of its fratricidal war.

So long as the United States is looking for a functional alliance and not for idealized founding fathers, it can find what it needs to shift the Syrian dynamic among the grab-bag of Syrian nationalists clamoring for American money and weapons on the northern front.

The framework for forming this alliance already exists. The United States, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other aligned players dispense military aid and cash to their preferred rebels through coordinating bodies—known colloquially among fighters as “military operations rooms”—in Reyhanli, Turkey and Aleppo, Syria. Some powers are believed also to fund favored proxies independently on the sly, but the operations rooms were founded with the stated goal of streamlining and unifying the funding of anti-Assad rebels.

And there is evidence to support this approach. Whenever the major outside powers work together to direct their weapons, funding, and intelligence in tandem, there are considerable gains on the ground as witnessed in the regime losses in Idlib and Aleppo provinces over the last year.16 When foreign powers work at loggerheads, fractiousness increases, along with infighting within and between the nationalist FSA, the Islamists, the Kurds, and the regime.

Changing the Dynamic on the Ground

The groups seeking aid through the operations rooms have proven their elasticity. Some, like the Noureddin Zinki Brigades, temporarily lost American backing when some of their weapons ended up in the hands of jihadists.17 Much of this leakage is unavoidable. For example, in Idlib province, the secular nationalist FSA brigades desperate to keep American support still operate at the pleasure of the militarily dominant Islamists.

This is a dynamic that the United States can change. First, it must make some tough choices in tandem with key allies: Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and perhaps other regional players such as Jordan and the United Arab Emirates. There are at least a dozen rebel groups well known to foreign governments. The foreign backers of the anti-Assad forces must agree on a small number of commanders and groups acceptable to all

Perfection will be the enemy of progress. None of the FSA militias are ideal, but most of them have nationalist roots and agree on the key points that inform long-term U.S. goals: preservation of Syria’s borders, a pluralistic state that safeguards the rights of all ethnic and sectarian communities, and an end to foreign domination of the state. Saudi Arabia will dislike Muslim Brotherhood militias. Turkey will prefer groups with a Sunni Islamic flavor and will seek to minimize the role of the Kurdish YPG militias. The United States will want a commander who pays lip service to America’s political vision for Syria. These lowest-common denominator characteristics can be found in a single militia.

The nationalist groups whose long term goal is to hold power in Syria also have come to understand that it’s not feasible to massacre members of minority groups, dictate terms to foreign powers, or transform Syria into an Islamic republic. A year ago, many FSA commanders interviewed in the border region were not willing to openly espouse nationalist political goal, or did not understand the type of political language that would enable them to win international support. Today, many of them have learned an entirely new vocabulary. FSA battalions have united in a coherent communications structure, which is ripe for sustained international backing.

An effective strategy would have to follow a long-term plan that includes, at a minimum, the following elements:

1. Coordinated backing of a single commander, or small number of commanders. The United States, Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia would have to direct their resources in harmony to selected groups and exclude funding and weapons for all others. As has occurred throughout the Syrian conflict whenever funding shifted, fighters would abandon atrophying brigades and join the well-funded and well-armed groups.

2. Effective governance of rebel areas. The foreign backers, led by the United States, would have to keep their proxies on a short leash, forcing rather than trusting them to behave well. That means long-term funding and arming that is dispensed in weekly bursts and carefully monitored. If a proxy group mistreats minorities, or engages in black market fuel trade, or extorts money from civilians, it will forfeit its weekly cash payment. The United States and others will also have to send huge amounts of nonmilitary aid to enable effective governance in liberated areas, which would require a full buy-in from Turkey.

3. Security in liberated areas. Unless liberated areas are safe for civilians, the regime will win even when it loses. There are many options, but all of them require an end to the Damascus regime’s unfettered control of Syria’s airspace. Curtailing the Syrian regime’s sovereignty would entail a significant change in U.S. commitment, which will require a change of position by the White House and political legwork domestically to win approval. The most maximal option is a no-fly zone supported by the United States and Turkey. In a less dramatic move, the United States could back a no-fly zone enforced by Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. It could politically support a middle option whereby Turkey would shoot down regime bombers and helicopters using land-based systems in Turkey. Or, at the most minimal, international teams of special forces (from Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey or the United States) could sporadically shoot down regime bombers using portable surface-to-air missiles. This last option would introduce enough risk and uncertainty for the regime that it would be forced to reduce its indiscriminate bombing. One reasonable objection is that most liberated areas are currently controlled by Islamist extremists: Ahrar al-Sham, Nusra, and ISIS. The United States understandably does not want to be seen acting as Al Qaeda’s air force, which is why it’s crucial that air cover evolves in tandem with backing for nationalist, non-jihadi rebels. Air cover and an internationally backed safe zone should be extended as a start over any area held by non-jihadi rebels.

4. Shifting the political and military balance of power. Gains by nationalist rebels would weaken the Islamists (ISIS, Nusra, and Ahrar) and would also weaken the regime. It is crucial that nationalist rebels, backed by the United States and others, win support and trust from fence-sitters, tribes, and rural religious Sunni Arabs who currently tilt toward Islamist groups or the regime. The U.S.-backed rebels would have to avoid sectarian massacres or Sunni triumphalism. They would have to continue showing an ability to work with all Syrian sects and ethnicities and continue espousing a commitment to a secular nationalist governing ideology that preserves Syria’s territorial integrity and opposes Islamist extremists. Such a position would make the rebels palatable to mainstream Syrians as well as to political actors with whom the opposition will ultimately have to reconcile in a negotiated settlement: quiescent members of the business class from every ethnic and sectarian background, the ruling elite, and its international backers.

5. A peace process. U.S.-orchestrated intervention on Syria’s northern front can feed a process of negotiating a political settlement. Rebels cannot win outright; neither can the regime or the Islamists. But a consolidated front of nationalist rebels can make peace with a subset of the regime and begin the arduous process of reconstituting the Syrian state. For a new strategy to succeed, the United States would have to regularly renew its invitation and commitment to support an inclusive political negotiating process to end the war.

A Long Haul

The United States has been mysteriously AWOL in Syria, even since “declaring war on ISIS” a year ago and undertaking a desultory bombing campaign. Now, with the peril of Iran’s nuclear program apparently contained, the United States ought to ramp up its diplomatic and indirect military engagement in Syria, with the intention of forcing a fair political settlement.

A concerted and sustained U.S.-orchestrated campaign to empower one faction of nationalist rebels could do wonders to change the dynamics of the fitful negotiations to resolve the Syrian civil war. There’s nothing the United States could do to make the anti-Assad rebels win, even if it wanted to. But by placing its thumb on the scale with a vigor that it has so far avoided, the United States could propel its preferred faction to dominance within the fractured milieu of anti-Assad forces.

The United States could alter the dynamic of the war and the position of key outside sponsors of the conflict—Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar—with a sustained political and military commitment to nationalist rebels who express a commitment to a multi-ethnic and multi-sectarian Syria within its current borders and based on an inclusive definition of citizenship.

Such a partnership is feasible, so long as it has realistic aims: not to win the war for one faction or hope to eliminate jihadist extremists overnight, but to make all parties to the civil war realize that a political compromise will leave them better off than a continued war.

The mechanics are clear. First, the United States must acknowledge that a resolution in Syria will require the involvement of all the parties to the conflict, including Washington’s unsavory allies and its persistent rivals. Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey will have to be at the negotiating table. So will some unseemly Islamist rebel factions. Any party excluded from negotiations, like ISIS or the Al Qaeda-affiliated Nusra Front, must be instead roundly defeated with military force. It is not possible to ignore the extremist groups and yet concede them the territory under their control.

Any new approach could still take years to change the overall direction of Syria’s war. A shift in the U.S. approach to the northern front would require considerable diplomatic work with Turkey and Arab allies. But a pragmatic plan could get the key players onside and frame the goals for the conflict in a more realistic way. Nothing will change as long as each group of combatants thinks it can achieve total victory. But the political dynamics will change as the balance of power on the ground shifts, and the only proven force that has affected the course of the conflict to date has been the sustained flow of money, weapons, and foreign political attention.

At worst, the United States will fail to persuade all its allies to fully cooperate with the strategy and will end up with a few tighter partnerships among the rebels, but no major strategic yield. At best, the United States will convince the other sponsors of the Syrian conflict that they no longer have free access to run killing fields and that they will have to pay a much higher price to stick with the status quo—or else will have to look for political compromises.

Notes

1 Estimates from the United Nations and Western news agencies place the minimum death toll at 230,000. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimates a minimum death toll of 320,000.

2 In addition to the 4 million refugees who have fled Syria, nearly 8 million internally displaced people have been forced from their homes but still live in the country. See Nick Cummings-Bruce, “Number of Syrian Refugees Climbs to More Than 4 Million,” New York Times, July 9, 2015,http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/09/world/middleeast/number-of-syrian-refugees-climbs-to-more-than-4-million.html?_r=0.

3 Sean D. Naylor, “Will Curbing Iran’s Nuclear Threat Boost Its Proxies?” Foreign Policy, July 20, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/07/20/will-curbing-irans-nuclear-threat-boost-its-proxies/.

4 Jessica Schulberg, “Obama: No End to War in Syria Without ‘Buy-In’ From Iran,” Huffington Post, July 20, 2015,http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/07/15/obama-iran-deal_n_7802768.html.

5 Jeremy Shapiro and Richard Sokolsky, “It’s Time to Stop Holding Saudi Arabia’s Hand,” Foreign Policy, May 12, 2015,http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/05/12/its-time-to-stop-holding-saudi-arabias-hand-gcc-summit-camp-david/.

6 David Gardner, “The Toxic Rivalry of Saudi Arabia and ISIS,” Financial Times, July 16, 2015, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/8bba2ab4-2b00-11e5-8613-e7aedbb7bdb7.html#axzz3gdqpeelg.

7 Semih Idiz, “Turkey Needs to Drop Its Dead-End Foreign Policy,” Al-Monitor, July 21, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/07/turkey-west-european-union-us-time-to-readjust-compass.html.

8 Adam Entous, “Assad Chemical Threat Mounts,” Wall Street Journal, June 28, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/assad-chemical-threat-mounts-1435535977.

9 Lucy Westcott, “United Nations: Assad’s Barrel Bombs Continue to Kill Syrian Civilians,” Newsweek, June 27, 2015,http://www.newsweek.com/united-nations-assads-barrel-bombs-continue-kill-syrian-civilians-347782.

10 Jennifer Rizzo, “Carter: U.S. Trains Only 60 Syrian Rebels,” CNN, July 7, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/07/politics/united-states-training-syrian-rebels-ashton-carter/.

11 See Roy Gutman, “First contingent of U.S.-trained fighters enters Syria,” McClatchy, July 16, 2015, http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/world/article27446395.html, and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “Syrian rebels get their first U.S.-trained fighters,” Washington Post, July 15, 2015,https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/first-us-trained-syrian-fighters-reenter-their-country/2015/07/15/6e6c0551-353d-4e17-961b-98995321576c_story.html.

12 See Denise Natali, “The Coalition’s quagmire with Syrian Kurds,” Al Monitor, July 14, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/07/coalition-quagmire-syrian-kurds.html#. See also Roy Gutman, “U.S Moves Its Syrian Air Campaign to the West,” McClatchy, June 30, 2015, http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/world/middle-east/article25909303.html.

13 Thomas Seibert, “ISIS is Losing in Northern Syria, but Ankara is Unhappy,” Daily Beast, June 16, 2015,http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/06/16/isis-is-losing-in-northern-syria-but-ankara-is-unhappy.html.

14Tim Arango, “ISIS Transforming Into Functioning State That Uses Terror as a Tool” New York Times, July 21, 2015,http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/22/world/middleeast/isis-transforming-into-functioning-state-that-uses-terror-as-tool.html.

15 See Liz Sly, “U.S.-backed Syria rebels routed by fighters linked to al-Qaeda,” Washington Post, November 2, 2014,https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/us-backed-syria-rebels-routed-by-fighters-linked-to-al-qaeda/2014/11/02/7a8b1351-8fb7-4f7e-a477-66ec0a0aaf34_story.html. Zack Beauchamp, “American strategy in Syria is collapsing,” Vox, November 4, 2014,http://www.vox.com/2014/11/4/7150473/american-strategy-in-syria-is-collapsing. A similar collapse struck another U.S. favorite, the Hazm movement; see Ian Black, “US Syria policy in tatters after favoured ‘moderate’ rebels disband,” Guardian, March 2, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/02/us-syria-policy-tatters-moderate-rebels-disband.

16 Firas abi Ali, “Syrian Opposition Success in Idlib Province Likely to Threaten Aleppo, Latakia, and Assad’s Hold on Power,” IHS Jane’s Intelligence Weekly, April 27, 2015, http://www.janes.com/article/51012/syrian-opposition-success-in-idlib-province-likely-to-threaten-aleppo-latakia-and-assad-s-hold-on-power.

17 Author interview with Noureddin Zinki Brigades official, Antakya, Turkey, June 2015.

Are We Witnessing the Birth of a New Mideast Order?

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

“The World Has Changed,” trumpeted the front-page headline of the Iranian reformist daily Etemaad on July 15, the day after Iran signed a nuclear deal with the six world powers. But as U.S. President Barack Obama attempts to build on this agreement, he will find that changing the destructive dynamics of the Middle East is far more difficult than any negotiation in Vienna.

For years, U.S. leaders have staked their hopes for calming decades of sectarian war, insurgency, and tension in the Middle East on rehabilitating Iran, a bête noire in the eyes of Washington and its allies. But if there’s any hope of changing these dynamics, the United States is going to have to dive quickly and deeply into the region’s feuds. Wars have spiraled out of control in four Arab countries, and Iran is only partly to blame. A more cooperative Tehran — which may or may not materialize after the nuclear agreement sinks in — could open the door to calming the bloodshed in Syria, where Iran is a lead player. But the roots of the wars in Iraq and Yemen go deeper than Tehran’s machinations, and Iran has almost no role in the Libyan conflict.

After the deal, like before, U.S. interests will be challenged by clever and aggressive foes, but also by ruthless allies. If the United States wants to alter the dynamic, it will have to give up its linear approach and play what Joseph Nye describes as “three-dimensional chess.” Until now, Washington has insisted on taking on one crisis at a time, meaning that a pileup of disasters has festered while the White House looked only at the Iran nuclear deal.

That mindset won’t work. It will take far more than a change in Iran to end the Syrian civil war. Same for Yemen.

So, what will work?

First, the United States will have to engage Iran and other bad actors in each of the region’s hot spots. Obama has already expressed the intention of doing so: At his press conference on July 15, he spoke of “[jump-starting] a process to resolve the civil war in Syria” and that “it’s important for [Iran] to be part of that conversation.”

Second, at the same time Washington tries to engage diplomatically with Tehran, it will also need to raise the costs for Iran of continuing to do business in the same bloody way it has across the region. With billions of dollars flowing back into the country after the lifting of sanctions, there’s a risk that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps will intensify its expansionist approach and investment in proxy wars. A direct war with Iran isn’t a wise option, but ignoring its machinations has left it free reign to expand its dominion in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen. The only remaining option is to engage in messy proxy warfare as well, giving sustained military and political backing to anti-Iranian proxies, which will make it expensive for Iran to meddle around the Arab world. This will give the United States a new card in the negotiations to come: It can offer to restrain its proxy militias if Iran does the same.

Third, the United States will face the challenging task of getting its recalcitrant allies onto the same page. In the Syria conflict, that will mean butting heads with Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, all of which have poured money into rival rebel factions, allowed a free-for-all in the border zones, and paved the way for the entrenchment of hard-line Islamists within the uprising. Washington will need to convince its partners to pick a single rebel coalition to back and then endow it with real and sustained support. That’s the only way to tilt the balance inside Syria and increase the likelihood of a political solution that empowers nationalist rebels at the expense of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the radical Islamists.

After years of myopic focus on Iran’s nuclear program, the United States will have to take an unsentimental and cleareyed inventory of its dysfunctional allies. It can only expect so much from Saudi Arabia, Israel, Egypt, and Turkey — but with these sorts of friends, it behooves Washington to lower its expectations and take a more transactional approach to enlisting cooperation, whenever possible, on a single issue or subsets of issues. A disappointed Saudi Arabia, for instance, might play ball with the United States on Syria — even as it opposes Washington’s policy in Iraq. Turkey could be convinced to better police its border in exchange for a U.S. policy shift on the Kurds, who have made rapid gains in northern Syria.

The biggest benefit of the Iran deal is the diplomatic process it created. The intense relationships that evolved over the course the negotiations can now be used to open conversations on other issues. Whether those conversations bear fruit is another matter — but history teaches us that personal trust among diplomats can change the direction on the ground.

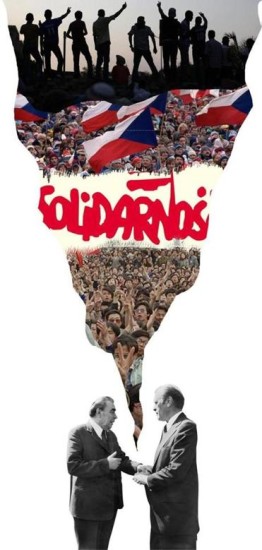

It would be a mistake, however, to think of this agreement as an inflection point akin to the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt, which completely shifted the dynamics of the Middle East conflict. The Iran nuclear talks are more like the Madrid process, the breakthrough that lead to the Oslo Accords: a first diplomatic step that could, in turn, lead to other diplomatic steps. And like the Oslo Accords, it could still ultimately fail to accomplish any of its stated goals.

So let’s not overstate the impact of the agreement just yet. The agreement hasn’t yet given the world any tangible achievements, in the form of abated extremism or disarmed militants. What’s more, the Middle East remains on course for another decade of murderous warfare, deepening sectarian feuds, and destabilizing polarization. These are grim phenomena with inescapable and dangerous strategic consequences for Middle Eastern countries, global energy markets, and the security interests of the United States.

If the Obama administration hopes to change this reality, it will need to pressure every major player — both allies and adversaries — to shift course. Iran, the Syrian regime, and Hezbollah could be emboldened by the deal and tempted to double down on their current maximalist bets. Troublesome friends such as Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, meanwhile, have continually undermined U.S. aims in the Middle East and will do so with even more boldness as they try to derail the nuclear deal.

Washington is going to need to change the calculations of both groups, and it’s not going to be easy. The Obama administration will have to manage petulant allies enraged by the deal and persuade drifting fence-sitters like Turkey and Egypt to play a more constructive role in breaking regional stalemates.

It will also have to defy recent history by rolling back Iranian influence at a time when Tehran will be motivated to try to expand its reach. Iran, after all, already successfully expanded its reach through militant proxies and tightened relations with key Arab allies even during the period when sanctions crippled its economy. With a deal concluded, Tehran won’t walk away from its achievements. If the nuclear negotiations were grueling, imagine how hard it will be to pressure Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to sacrifice a material alliance with Syria, Iraq, or Hezbollah.

For years, Obama administration insiders have quietly spread the word that the president wasn’t tuned out on the Middle East. Instead, they argued, he was following a strategic order of operations. The first step was trying to seal a nuclear deal with Iran, the regional tiger, and then systematically deal with the region’s instability, proxy wars, and sectarian strife.

The coming months will test that claim. If Obama does in fact have a plan to use an Iran deal as the cornerstone of a new regional order, the real work begins now, and it will be messy. The dirty business of superpower realpolitik, a combination of muscle and diplomatic savvy, comes next. It’s what the United States should have been doing all along. The Iran deal gives it a chance to reboot and get it right.

A Syrian Parody Features the Civil War, and Is Stalked by It

[Published in The New York Times.]

GAZIANTEP, Turkey — The worst day on the set of “Banned in Syria,” the actors agreed, was when the sniper struck in June. A location scout was preparing for the day’s filming when a single bullet killed him instantly.

The cast and crew continued undeterred. That is the bargain when you sign up to produce a rebel television series in the wartime Syrian city of Aleppo with little pay, no insurance and militias that want you dead.

During a marathon filming in June to rush this season’s episodes to air in time for Ramadan, the producers of “Banned in Syria” overcame obstacles from the lethal to the prosaic. A second crew member was wounded in crossfire and died several days later. Barrel bombs and shells derailed scenes. Out of respect, filming also paused during the frequent passing funerals. At the end of each day, the technicians struggled with the painfully slow Internet connections as they uploaded footage to film editors at the office just across the border here in Gaziantep.

A scene from the episode “Genie, Genie,” one of the most popular of “Banned in Syria.” It features a dimwitted genie fielding the poignant but comical wishes of the denizens of Aleppo. Credit: Lamba Productions

The creators of “Banned in Syria,” a show that parodies all sides in Syria’s civil war, are desperate for their work to succeed as profitable entertainment — and as political satire.

Most of the scenes take place in the rubble-strewn streets of Aleppo or in damaged buildings. The show skewers President Bashar al-Assad and his government, as well as the religious groups that have taken over much of the uprising. It even mocks the rebels in the Free Syrian Army, who provide security when the show is filmed on location.

“We make fun of the way they treat civilians, but they have no choice but to protect us,” said Yamen Nour, one of the stars of the show. Mr. Nour, 37, a painter and actor who led demonstrations in 2011, considers his theater and television work a continuation of the revolution by other means.

“We want to show people that we are still living,” he said. “It’s very difficult to make people smile during war. We want them to forget the war for a moment.”

Tony el-Taieb, 24, the producer of the series, said he and the 55 or so actors and crew members who work for his company, Lamba Productions, believed that Syria’s original revolutionaries must establish cultural alternatives to those generated by the government in Damascus.

“Our videos drive the regime crazy, because we show the reality,” Mr. Taieb said. “We can’t leave the field of drama to the regime.”

The political ethos of “Banned in Syria” and of Lamba is quintessentially urban and cosmopolitan — the spirit of the original nonviolent uprising in 2011 against Mr. Assad that preceded the civil war. The idea was to broach every taboo subject big and small: the fawning respect accorded to military officers, family feuds and even religion.

To minimize danger, Lamba does editing and postproduction in an apartment here, but Mr. Taieb insisted that filming, theater production and most radio broadcasting take place in Aleppo, a divided city that was once Syria’s economic powerhouse and now symbolizes the society’s intractable divisions and the wanton destruction of the four-year war.

“Banned in Syria” airs on Aleppo Today, a channel for revolutionaries, but Mr. Taieb said the serial gets most of its views on YouTube. He has received messages from friends and relatives of officials about recent episodes, and the comments on YouTube and Facebook suggest that government stalwarts and active-duty soldiers are among the fans of the series.

“We’re talking about everything you can’t discuss in Damascus, because there the walls have ears,” Mr. Taieb said.

A lawyer and activist from a wealthy Sunni Muslim family in Aleppo, Mr. Taieb, whose real name is Qusai Hayani, adopted a Christian nom de guerre when the uprising began in the hopes of persuading minority friends to join the revolution.

While rebel militia ranks are overwhelmingly Sunni, Lamba Productions reflects Syria’s ethnic and sectarian diversity, with team members representing Alawites, Christians, Druse and Kurds.

Authenticity is important to the producers, but then so is staying on budget. The cast and crew members said they supported filming the series inside what they considered “liberated Syria,” but they also realized they could not afford multiple takes.

The resulting complications are visible in “Genie, Genie,” one of this season’s most popular episodes, featuring a dimwitted djinn fielding poignant but comical wishes from the denizens of an apocalyptic Aleppo.

“The passport you gave me was fake!” complains the hapless Syrian, played by Jihad Saka Abu Joud, 32, who found a magic lamp in the ruins of his home.

“Sorry,” replies the genie, played by Mr. Nour. “My supplier is a jerk.”

A real-life shell explodes in the background, a puff of smoke visible in the frame. The ersatz genie delivers his next line without missing a beat. Mr. Abu Joud flinches then recovers. The take rolls on.

Mr. Abu Joud can mug like the British character Mr. Bean, but he has gained notoriety for another talent: singing ballads. During breaks, Mr. Abu Joud regaled the crew with revolutionary songs, though he feared Aleppo residents would resent them or consider them frivolous. He discovered the opposite, however.

In an encounter captured on video, Mr. Abu Joud stops singing as a funeral procession approaches. The father of the deceased orders Mr. Abu Joud to resume and dances as his grieving family intermingles with the “Banned in Syria” crew.

“This support gives us a lot of power,” Mr. Abu Joud said.

The last episodes were still being edited during the first week of Ramadan, in the middle of June, in a fevered rush. After midnight during one of those sessions, some of the actors and Mr. Taieb gathered around a monitor to admire the genie episode. The unpacked bags of equipment from the filming in Aleppo were still piled in a jumble by the door.

Although the team is mostly secular and includes several non-Muslims, it refrained from eating and smoking in the common areas of the office during the Ramadan fast. After sunset, though, the Bohemian air returned. Coffee cups littered the tables and a haze of cigarette smoke reduced visibility across the room.

Most of the actors are wanted by the government. Mr. Taieb’s father was held for nearly a year, and the brother of another player, Zakaria Abdelkafi, remains in prison.

For all the risk and the weighty mission, the actors and producers seem to be having a good time. As the crew finished the postproduction work for “Banned in Syria,” they were already developing a concept for a 24-minute drama about a journalist covering Syria’s war and future comedic pieces.

And while filming during a civil war is less than ideal, there is at least one production benefit.

“If there were no war, our work would take much longer,” Mr. Nour said.

Others on the team agreed.

“Can you imagine how long it would take to build the set of a destroyed building?” Mr. Abu Joud said. “Thanks to the war, it’s all ready to go.”

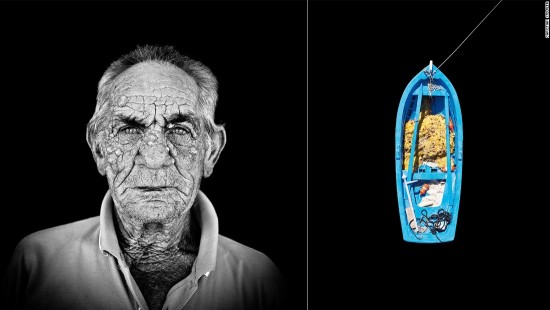

Permanent refugees reshape the Middle East

PHOTO: ADEM ALTAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

A woman and a child left a Syrian shop in Mersin in March.

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas]