Alaa Abdel Fattah on this moment of suspended hope

Alaa Abdel Fattah has been one of the most interesting thinkers and actors of the Egyptian revolution. He knows politics, history and street activism, and he’s put his body and his mind fully into the struggle against authoritarianism for his entire life. He’s not always right, but he never has stopped thinking strategically and philosophically about the revolution, with a sincere willingness to admit mistakes and learn from them. He’s done so at every juncture in good faith and with an unerring moral compass. (I think along with Amr Hamzawy he’s been unique in trying to think in historical-political terms while also partaking directly in the struggle.) Fresh out of prison, he talked to Sherif Abdel Kouddous on Democracy Now! yesterday. The whole hour is worth listening to, but I was drawn to Alaa’s final comments about why he uses the word “defeat”:

But for it to be a revolution, you have to have a narrative that brings all the different forms of resistance together, and you have to have hope. You know, you have to be—it has to be that people are mobilizing, not out of desperation, but out of a clear sense that something other than this life of despair is possible. And that’s, right now, a tough one, so that’s why right now I talk about defeat. I talk about defeat because I cannot even express hope anymore, but hopefully that’s temporary.

What line did Putin cross in Crimea?

[The Internationalist column published in the The Boston Globe Ideas.]

WHAT HAPPENED IN UKRAINE over the past month left even veteran policy-watchers shaking their heads. One day, citizens were serving tea to the heroic demonstrators in Kiev’s Euromaidan, united against an authoritarian president. Almost the next, anonymous special forces fighters in balaclavas were swarming Crimea, answering to no known leader or government, while Europe and the United States grasped in vain for ways to influence events.

Within days, the population of Crimea had voted in a hastily organized referendum to join Russia, and Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, had signed the annexation treaty formally absorbing the strategic peninsula into his nation.

As the dust settles, Western leaders have had to come to terms not only with a new division of Ukraine, but its unsettling implications for how the world works. Part of the shock is in Putin’s tactics, which blended an old-fashioned invasion with some degree of democratic process within the region, and added a dollop of modern insurgent strategies for good measure.

Vladimir Putin at the Plesetsk cosmodrome launch site in northern Russia./PRESIDENTIAL PRESS SERVICE VIA REUTERS

But when policy specialists look at the results, they see a starker turning point. Putin’s annexation of the Crimea is a break in the order that America and its allies have come to rely on since the end of the Cold War—namely, one in which major powers only intervene militarily when they have an international consensus on their side, or failing that, when they’re not crossing a rival power’s red lines. It is a balance that has kept the world free of confrontations between its most powerful militaries, and which has, in particular, given the United States, as the most powerful superpower of all, an unusually wide range of motion in the world. As it crumbles, it has left policymakers scrambling to figure out both how to respond, and just how far an emboldened Russia might go.

***

“WE LIVE IN A DIFFERENT WORLD than we did less than a month ago,” NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen said in March. Ukraine could witness more fighting, he warned; the conflict could also spread to other countries on Russia’s borders.

Up until the Crimea crisis began, the world we lived in looked more predictable. The fall of the Berlin Wall a quarter century ago ushered in an era of international comity and institution building not seen since the birth of the United Nations in 1945. International trade agreements proliferated at a dizzying speed. NATO quickly expanded into the heart of the former Soviet bloc, and lawyers designed an International Criminal Court to punish war crimes and constrain state interests.

Only small-to-middling powers like Iran, Israel, and North Korea ignored the conventions of the age of integration and humanitarianism—and their actions only had regional impact, never posing a global strategic threat. The largest powers—the United States, Russia, and China—abided by what amounted to an international gentleman’s agreement not to use their military for direct territorial gains or to meddle in a rival’s immediate sphere of influence. European powers, through NATO, adopted a defensive crouch. The United States, as the world’s dominant military and economic power, maintained the most freedom to act unilaterally, as long as it steered clear of confrontation with Russia or China. It carefully sought international support for its military interventions, even building a “Coalition of the Willing” for its 2003 invasion of Iraq, which was not approved by the United Nations. The Iraq war grated at other world powers that couldn’t embark on military adventures of their own; but despite the irritation the United States provoked, American policymakers and strategists felt confident that the United States was obeying the unspoken rules.

If the world community has seemed bewildered by how to respond to Putin’s moves in Crimea over the last month, it’s because Russia has so abruptly interrupted this narrative. Using Russia’s incontestable military might, with the backing of Ukrainians in a subset of that country, he took over a chunk of territory featuring the valuable warm-water port of Sevastopol. The boldness of this move left behind the sanctions and other delicate moves that have become established as persuasive tactics. Suddenly, it seemed, there was no way to halt Russia without outright war.

Some analysts say that Putin appears to have identified a loophole in the post-Cold War world. The sole superpower, the United States, likes to put problems in neat, separate categories that can be dealt with by the military, by police action or by international institutions. When a problem blurs those boundaries—pirates on the high seas, drug cartels with submarines and military-grade weapons—Western governments don’t know what to do. Today, international norms and institutions aren’t configured to react quickly to a legitimate great power willing to use force to get what it wants.

“We have these paradigms in the West about what’s considered policing, and what’s considered warfare, and Putin is riding right up the middle of that,” said Janine Davidson, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former US Air Force officer who believes that Putin’s actions will force the United States to update its approach to modern warfare. “What he’s doing is very clever.”

For obvious reasons, a central concern is how Putin might make use of his Crimean playbook next. He could, for example, try to engineer an ethnic provocation, or a supposedly spontaneous uprising, in any of the near-Russian republics that threatens to ally too closely with the West. Mark Kramer, director of Harvard University’s Project on Cold War Studies, said that Putin has “enunciated his own doctrine of preemptive intervention on behalf of Russian communities in neighboring countries.”

There have been intimations of this approach before. In 2008, Russian infantry pushed into two enclaves in neighboring Georgia, citing claims—which later proved false—that thousands of ethnic Russians were being massacred. Russia quickly routed the Georgian military and took over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Today the disputed enclaves hover in a sort of twilight zone; they’ve declared independence but were recognized only by Moscow and a few of its allies. Ever since then, Georgian politicians have warned that Russia might do the same thing again: The country could seize a land corridor to Armenia, or try to absorb Moldova, the rest of Ukraine, or even the Baltic States, the only former Soviet Republics to join both NATO and the European Union.

Others see Putin’s reach as limited at best to places where meaningful military resistance is absent and state control weak. Even in Ukraine, Russia experts say, Putin seemed content to wield influence through friendly leaders until protests ran the Ukrainian president out of town and left a power vacuum that alarmed Moscow. Graham, the former Bush administration official, said it would be a long shot for Putin to move his military into other republics: There are few places with Crimea’s combination of an ethnic Russian enclave, an absence of state authority, and little risk of Western intervention.

The larger worry, of course, is who else might want to follow Russia’s example. China is the clearest concern, and from time to time has shown signs of trying to throw its weight around its region, especially in disputed areas of the South China Sea. But so far it has been Chinese fishing boats and coast guard vessels harassing foreign fishermen, with the Chinese navy carefully staying away in order not to trigger a military response. For the moment, at least, Putin seems willing to upend this delicately balanced world order on his own.

***

THE INTERNATIONAL community’s flat-footed response in Crimea raises clear questions: What should the United States and its allies do if this kind of land grab happens again—and is there a way to prevent such moves in the first place?

“This is a new period that calls for a new strategy,” said Michael A. McFaul, who stepped down as US ambassador to Russia a few weeks before the Crimea crisis. “Putin has made it clear that he doesn’t care what the West thinks.”

So far the international response has entailed soft power pressure that is designed to have an effect over the long term. The United States and some European governments have instated limited economic sanctions targeting some of Putin’s close advisers, and Russia has been kicked out of the G-8. There’s talk of reinvigorating NATO to discourage Putin from further adventurism. So far, though, NATO has turned out to be a blunt instrument: great for unifying its members to respond to a direct attack, but clumsy at projecting power beyond its boundaries. As Putin reorients away from the West and toward a Greater Russia, it remains to be seen whether soft-power deterrents matter to him at all.

Beyond these immediate measures, American experts are surprisingly short on specific suggestions about what more to do, perhaps because it’s been so long since they’ve had to contemplate a major rival engaging in such aggressive behavior. At the hawkish end, people like Davidson worry that Putin could repeat his expansion unless he sees a clear threat of military intervention to stop him. She thinks the United States and NATO ought to place advisers and hardware in the former Soviet republics, creating arrangements that signal Western military commitment. It’s a delicate dance, she said; the West has to be careful not to provoke further aggression while creating enough uncertainty to deter Putin.

Other observers in the field have made more modest economic proposals. Some have urged major investment in the economies of contested countries like Ukraine and Moldova, at the scale of the post-World War II Marshall Plan, and a long-term plan to wean Western Europe off Russian natural gas supplies, through which Moscow has gained enormous leverage, especially over Germany.

Davidson, however, believes that a deeper rethink is necessary, so that the United States won’t get tied up in knots or outflanked every time a powerful nation like Russia uses the stealthy¸ unpredictable tactics of non-state actors to pursue its goals. “We need to look at our definitions of military and law enforcement,” she said. “What’s a crime? What’s an aggressive act that requires a military response?”

McFaul, the former ambassador, said we’re in for a new age of confrontation because of Putin’s choices, and both the United States and Russia will find it more difficult to achieve their goals. In retrospect, he said, we’ll realize that the first decades after the Cold War offered a unique kind of safety, a de facto moratorium on Great Power hardball. That lull now seems to be over.

“It’s a tragic moment,” McFaul said.

Medical care is now a tool of war

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT — The medical students disappeared on a run to the Aleppo suburbs. It was 2011, the first year of the Syrian uprising, and they were taking bandages and medicine to communities that had rebelled against the brutal Assad regime. A few days later, the students’ bodies, bruised and broken, were dumped on their parents’ doorsteps.

Dr. Fouad M. Fouad, a surgeon and prominent figure in Syrian public health, knew some of the students who had been killed. And he knew what their deaths meant. The laws of war—in which medical personnel are allowed to treat everybody equally, combatants and civilians from any side—no longer applied in Syria.

“The message was clear: Even taking medicine to civilians in opposition areas was a crime,” he recalled.

As the war accelerated, Syria’s medical system was dragged further into the conflict. Government officials ordered Fouad and his colleagues to withhold treatment from people who supported the opposition, even if they weren’t combatants. The regime canceled polio vaccinations in opposition areas, allowing a preventable disease to take hold. And it wasn’t just the regime: Opposition fighters found doctors and their families a soft target for kidnapping; doctors always had some cash and tended not to have special protection like other wealthy Syrians.

Doctors began to flee Syria, Fouad among them. He left for Beirut in 2012. By last year, according to a United Nations working group, the number of doctors in Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, had plummeted from more than 5,000 to just 36.

Since then, Fouad has joined a small but growing group of doctors trying to persuade global policy makers—starting with the world’s public health community—to pay more urgent attention to how profoundly new types of war are transforming medicine and public health. In a recent article in the medical journal The Lancet, Fouad and a team of researchers looked closely at the conflicts in Iraq and Syria and found that the impact of what they call the “militarization of health care” in modern wars goes far beyond the safety of combat zone doctors, ensnaring even uninvolved civilians, with effects that can persist for years.

Other groups have begun focusing on the change as well. The International Committee of the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders have documented and condemned disruptions of medical care by combatants. The entirety of the most recent issue of the journal Public Health is dedicated to a critical assessment of the failure of the World Health Organization to adapt to the new realities of conflict.

Fouad and his Lancet coauthors say—reasonably—that any new global policy norms for wartime health care ultimately need to be hashed out in the security and political realms, not by doctors. But doctors, especially public-health specialists, have a crucial role to play: They gather the data and define the issues that drive much of global health policy. And as war has become a free-for-all, dissolving the rules that long protected medical care, Fouad and his coauthors suggest that their own field has been slow to awaken to the importance of that change.

“To be honest, we are stuck in this problem, and we don’t know what to do,” said Omar Al-Dewachi, a physician and anthropologist at the American University of Beirut, and the lead author of the Lancet paper. “The first thing is to start a conversation, and come up with new tools.”

What will replace the current system is far from clear, they say, but it’s time to start figuring it out: Right now, war has a quarter-century headstart.

***

UNTIL RECENTLY, medical care was something of a bright spot in the history of conflict. Major European powers, shocked by the suffering and grisly deaths of their soldiers in the Crimean War, agreed in 1864 to the First Geneva Convention. It granted medical workers a special neutral status on the battlefield, and upheld the right of all wounded to medical care regardless of nationality.

It was the first article of international humanitarian law and became the cornerstone of all subsequent Geneva Conventions. When we talk about “crimes against humanity” and “war crimes,” we’re usually referring to the body of law that arose over the next century and half, built on the narrow foundation of neutral, universal medical care for combatants in the battle zone. There were always breakdowns and violations, but the laws of war were remarkably effective at limiting abuse, establishing taboos, and shaming the worst offenders.

That relative comity disappeared with the end of the Cold War. When the rival superpowers were locked in combat, they had an incentive to promote the laws of war; they didn’t want their own fighters mistreated if there were another world war. But with the United States and Soviet Union no longer in direct armed confrontation, small wars across the globe flared with new ferocity and fewer scruples.

The wars of the 1990s spread in shocking new ways, with widespread torture, starvation, and genocidal murder campaigns. Rather than fighting other soldiers, armed groups often concentrated on battling civilians. The Geneva Conventions barely figured for the combatants in the former Yugoslavia, Somalia, Rwanda, the Congo, and Afghanistan. The United States contributed to that decline after 9/11 when it suspended Geneva Convention protections for prisoners in the “war on terror,” and normalized drone strikes against targets in civilian areas.

The protections around medical care started to collapse as well. Dr. Jennifer Leaning, director of Harvard University’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, has worked in conflict zones for decades and has surveyed the eroding conditions of medical care. Increasingly, she found, the biggest victims in armed conflicts weren’t the combatants but the civilian populations suffering in scorched-earth or ethnic cleansing campaigns in which doctors and hospitals became explicit, rather than incidental, targets.

The final strike against medical neutrality, Leaning says, came in the last decade during America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Insurgents targeted anyone connected to the “Western” side of the conflict, even local health care workers treating patients in public hospitals. The CIA used a polio inoculation campaign to gather information in its hunt for Osama bin Laden; ever since, Pakistani mullahs have condemned vaccination workers. By the time civil war broke out in Syria, the equal right to medical care in combat zones existed only on paper.

“What is now happening is the violation of deeply held legal norms that have taken 150 years of work,” Leaning said in an interview. “That is what is appalling.”

It’s been commonplace in the last decade in Iraq and Syria for militias to enter hospitals with guns drawn, and order doctors to treat their comrades instead of civilians. In the early 1990s in Mogadishu, such behavior was an oddity. In Baghdad in 2006, Shia death squads took over entire hospitals and infiltrated the health ministry, denying health care to Sunnis and even hunting down rivals in their sickbeds.

Doctors are also starting to document how a war-torn region’s health problems can continue even when dramatic violence subsides. Once a functioning health care system is destroyed, it can take years or decades to rebuild. Al-Dewachi worked as a physician in Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War, and has had a close view of how a war’s medical impact can persist and spread. With Iraq’s hospital system in shambles and doctors constantly emigrating to safer places, patients have flowed over borders, often seeking medical treatment at great cost in the relatively stable hospitals of Beirut. Even when Iraq is supposedly calm, the stream of patients never abates, he said. “It’s an invisible story of the war,” Al-Dewachi said. “The long-term effects continue even when the fighting stops.”

***

WITH THE OLD SYSTEM broken, what should replace it? This is where it gets hard. Stateless rebels and insurgent groups, by definition, aren’t signatories to any international agreements. And the entire shape of modern warfare looks nothing like the formal battlefields that gave rise to the Geneva Conventions.

“We have to build new tools, new concepts, new institutions, that adapt to this concept of conflict,” Fouad said.

On the ground, under fire, health workers have improvised solutions. One common response has been to withdraw completely, only returning if combatants agree to respect the neutrality of clinics. At various times, groups as tough as Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross have temporarily shut down operations when they were targeted in vicious conflict zone. Some aid groups have used private diplomacy to negotiate protected, equal access to government and rebel areas.

Leaning notes that some medical-aid groups have resorted to armed guards for clinics and vaccine workers, while other health care workers have evolved to function like military medics, embedded with combat forces and providing care on the run.

As for the longer-term effects, the recent Lancet paper suggests some ways for the public health community to rethink its approach to medical care in war zones—starting with its definition of what counts as a war zone.

Health care is normally a massive undertaking that operates through fixed channels—governments, national budgets, and clinics, with clear borders and supply chains. The paper suggests it’s time to scrap this notion when it comes to war zones: One facet of modern conflict is that it obeys no geographical limits. The researchers suggest that the global health community adopt a notion of shifting “therapeutic geographies” that acknowledges people caught in modern conflicts may change where they live—and where they get health care—from day to day, week to week.

That concept, abstract as it sounds, would mark a significant departure in global public health. The World Health Organization, the single most important international body dealing with health matters, still operates almost entirely through diplomatic channels, dealing only with the sovereign government even in complex, multisided conflicts like Syria’s. That means that when the regime wants to isolate a rebel province, WHO can’t vaccinate people there and other UN agencies might not be allowed to deliver emergency food aid. Health organizations and other humanitarian agencies will have to work with nonstate actors and militias, as well as governments, if they want to be able to operate throughout a war-affected area.

Public health research can also put more energy into measuring the human toll of war beyond the battlefield. Part of the recent Lancet paper is a strong call for doctors to start quantifying the effects of modern war on health, looking broadly at its full impact. “At this point, we need to just pay attention and describe what’s going on,” said Al-Dewachi.

The effects of better data could be political as well as medical, the authors suggest: A clear picture of the full health impact of war might well change the justification for future “humanitarian interventions.”

Today, Fouad’s former home of Aleppo is largely a ghost town, its population displaced to safer parts of Syria or across the border to Turkey and Lebanon. The city’s former residents carry the medical consequences of war to their new homes, Fouad said—not just injuries, but effects as varied as smoking rates, untreated cancer, and scabies. Wars like those in Syria and Iraq don’t follow the old rules, and their effects don’t stop at the border.

The researchers are energized by their quest to reorient the public health field, but they betray a certain world weariness when asked what might replace the current order, and provide better care for the millions harmed by today’s boundary-less wars.

“If I knew,” Al-Dewachi said, “I would be involved with it.”

Processing the Arab Revolts

While finishing work on my book manuscript I came across this video from an October 2013 talk I gave at Claremont MacKenna College. I share it here mainly so that my mother can watch it, but it captures my thinking at a moment when the forces of reaction were consolidating power and crushing dissent across the Arab region. This talk was one of my first attempts to synthesize the different regional events and at the same time find some reason to remain hopeful. Four months later there’s even less reason to retain even a shred of optimism.

A revolutionary playwright: Saadallah Wannous

Steve Wakeem, as Sheikh Qassim, the Mufti, delivers a religious decree. Photo: ALEXY FRANGIEH

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT

Citizens in Damascus were up in arms. An autocrat’s impetuous power grabs and flagrant infidelity had split the city’s ruling clans, while fundamentalist clerics issued blanket fatwas against “immoral behavior.”

The year was 1880. The contretemps quickly subsided, a footnote in Ottoman history. But in December it formed the backbone of a gripping play that delivered a stark critique of power and conservative social mores in the Arab world.

Staged for the first time in English by the American University of Beirut, “Rituals of Signs and Transformations,” a 1994 play by the late Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous, made a splash even in a city known for its relatively freewheeling culture. In literary circles, Wannous has long been considered a giant of Arab literature, but his work has rarely been performed in the region where he lived and worked.

Before his death in 1997, Wannous achieved renown not just as a Syrian dissident writer, but as a playwright on a par with Bertolt Brecht and Wole Soyinka. Politically, his plays in Arabic were akin to Vaclav Havel’s in Iron Curtain Czechoslovakia: They used the thin fictions of the theater to offer social criticism that would be otherwise unthinkable.

Like Havel, Wannous always saw himself as more than a playwright: He spent his life articulating a critique of authoritarianism, religious hypocrisy, and social repression. Up until his death, he was convinced that his plays were laying the groundwork for a complete reinvention of Arab society.

Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous reads a message at UNESCO’s World Theatre Day.

STR NEW/REUTERS

Today, something of a rediscovery of Wannous’s work is underway: “Rituals” has been performed recently in Cairo and Paris, and a collection of his plays has just been published by the City University of New York. Despite it being in English translation, every performance of the play “Rituals” this month played to a full house of people eager to see Wannous’s ribald skewering of official sanctimony and social rigidity.

But the social revolution the playwright hoped for is still far off—and the eager audience for his rarely performed work is evidence of the immense hunger for an honest intellectual dialogue about the crisis in Arab society. Today, even in the arts, dissent like Wannous’s remains unusual here. And that work like his is so compelling, and yet hard to find, is a testament to just how narrow the scope of the region’s political dialogue has become.

***

WANNOUS WAS BORN in a poor rural village in 1941, a member of the Alawite minority whose members would come to control the Syrian government, and came of age during the 1960s, the peak years of both the Cold War and Arab nationalism. Syria tried to solve its domestic problems by uniting with Egypt, part of a doomed project to create single “pan-Arab” government for the Middle East and North Africa. It failed, leaving Syria and the rest of the Arab world to seek protection as clients of the Cold War powers. Damascus fell squarely in the Soviet camp, and the authoritarian state it created was modeled directly on those of its Eastern bloc counterparts.

In an irony that many in those Communist states would have recognized, Wannous drew a paycheck for much of his life from the very regime that he excoriated in his plays. After studying journalism in Cairo, he held jobs as a critic and a government bureaucrat, while writing plays on his own time. He edited cultural coverage for government newspapers, and established his own journals when his critical views made that impossible. During a stint in Paris as a cultural journalist, he met key writers of his time, including Jean Genet and Eugène Ionesco. Wannous ended up in charge of the Syrian government’s theater administration, which followed a Soviet model, generously supporting an arts scene that buttressed the regime’s values.

By the 1970s, the Assad regime had consolidated power and was fomenting anti-Israel militants around the region while avoiding direct conflict on its own border. Wannous rejected wholesale the primacy of the ruling Alawite minority, and his moral stances, presented in unusually vital dialogue and characters drawn as human beings rather than archetypes, established him as a major Arab writer of his generation.

Wannous’s work shares themes with other global dissident literature: In his play “The King is the King,” for example, a beggar successfully takes the place of the monarch, putting the lie to the claim that there’s anything unique about a divine ruler—or the dictator of Syria, for that matter. Every night at curtain call during its Damascus run, the director placed the stage-prop crown on Wannous’s head, to thundering applause.

“To this day, I don’t understand why it was allowed,” his daughter Dima said in an interview.

During his lifetime, Wannous himself said that he was allowed to write and live in Syria only so that the regime could pretend to the world that it tolerated free speech. He took full advantage of that liberty, savaging the failures of Arab nationalism and the autocrats who spawned it. He broke several taboos in “The Rape,” which as an epilogue featured a character named Wannous discussing the prospects for healing with an Israeli psychiatrist—a conversation that in real life would have been illegal.

As a body of work, his plays amounted to an argument that Arab society needed to break out of the political and social constraints that kept it locked in place. Confronted by his region’s stagnation and powerlessness, Wannous preserved a kind of optimism: The solution, he believed, lay within the Arab world and its citizens. He chafed at the convention of writing in classical Arabic, and wished writers felt free to reach more people by addressing their audience in colloquial language. He himself wrote his first drafts in the colloquial and then translated them into classical Arabic.

He bucked convention in other ways, too. In “Rape,” he depicts an Israeli soldier whose crimes against Palestinians distort his own psyche. But, crucially, he portrays other Israeli characters with empathy—not everyone is a villain—and he suggests there is value in engagement between Arabs and their Israeli enemies.

In “Rituals of Signs and Transformations,” which many critics consider his masterpiece, Wannous took aim at all the Arab world’s sacred cows in one shot. In the play, the mufti of Damascus—the city’s top religious official—feuds with a local rival, the naqib, leader of the nobility. But then the naqib is arrested cavorting with a prostitute, threatening the authority of all the religious leaders. The mufti sets aside his religious principles and schemes to save his erstwhile enemy. The only completely honorable characters are the naqib’s wife, who divorces him and chooses to work as a prostitute herself, and a local tough who’s dumped by his male lover when he decides he wants to be open about his love. A policeman who tries to enforce the law and tell the truth is thrown in jail and branded insane.

The play was never performed in Syria during Wannous’s lifetime. The official excuse was that the sets were too bulky to import from Beirut, where a truncated version had been staged, but it couldn’t have helped that the real-life mufti of Aleppo issued a fatwa against the play. Even in Beirut, the director avoided state censorship by calling the mufti by another name.

That might sound like an evasion from another era, but little has changed. The director of last month’s production also changed the title of the mufti, using the less-religious “sheikh.” Lebanon’s censor regularly shuts down plays, concerts, and other performances; to reduce the likelihood of censorship, the AUB producers didn’t charge for tickets. During the final performance, emboldened by the show’s success, some of the actors reverted to Wannous’ original language, calling the character “mufti.”

“I told them that if we got fined, they would have to pay it,” said the director, Sahar Assaf.

***

SEEN TODAY, “Rituals” still falls afoul of numerous taboos in the Middle East, from its attack on authority and religious hypocrisy to its unvarnished portrayal of child abuse, rape, and the persecution of gay people and women who seek equal rights. The audiences squirmed as much during the tender love scene between two men as during the soliloquies that reveal the mufti as a power-hungry schemer and another vaunted religious scholar as a serial child molester.

The continued power of Wannous’s work illustrates both his success as an artist and his failure, at least so far, to unleash the societal transformation for which he yearned. He aspired for a society where individuals could live free from tyranny, including the tyranny of his own Alawite sect. These are still not opinions that establishment Syrians are expected to discuss aloud. His daughter Dima, a journalist and fiction writer, last summer wrote approvingly about the spread of the war to Alawite areas. “Now they too will know what it means to be Syrian,” she said. She drew death threats from her father’s relatives.

“He thought his plays would transform Arab society, and all his life he was disappointed that they did not,” said Robert Myers, the playwright and AUB professor who cotranslated “Rituals.” “He thought his plays would ignite a revolution in thinking.”

One of the Wannous’s best-known lines comes not from a play but from the speech he delivered for UNESCO’s World Theater Day in 1996. It was the first time an Arab had been granted the honor, and it’s fair to assume Wannous knew he was speaking for posterity. “We are condemned to hope,” he said, “and what is taking place today cannot be the end of history.” At the time, he was speaking of the decrepit state of theater in the Arab world, but the phrase has lived on as a wider slogan.

Today the tradition Wannous embodied—the high-profile artist-intellectual driving a national conversation—is almost vanished itself. Throughout the Arab world, the publishing business has long been in decline. Millions watch high-end Arabic television serials, but only a few thousand attend theater productions. Most of the great dissident intellectuals are dead, and none in the new generation have achieved political influence. “Today’s intellectuals didn’t start the revolutions. That’s why they have to follow the people instead of leading them,” said Dima Wannous. She finds it particularly galling that sectarian religious fundamentalists have come to dominate the uprising in Syria, which she has been forced to flee because of threats.

Yet it’s also possible to see in Syria a testament to the staying power of Wannous’s ideas. The dream of a secular democratic state, the local initiatives to deliver food and health care, and especially, the early days of the revolt that pitted nonviolent citizens against a pitiless regime, all hark back to the ideals of Wannous—namely, his rejection of received authority and belief that if something better happens, it will arise from within. In 2011, when demonstrators first marched demanding the resignation of Bashar Assad, the signs some brandished read: “We are condemned to hope.”

Lessons from 2013: Regime Power rivals People Power

The Boston Globe Ideas section put together a package of year-end lessons. My depressed contribution was that –sadly — we can’t discount nasty old regimes simply because they’re nasty. [Original link behind paywall here.]

JUST A FEW YEARS AGO, people power seemed unstoppable. Arab revolts in 2010 and 2011 overthrew a quartet of tyrants—Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia, Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen, and Moammar Khadafy in Libya. Vast police states proved no match for crowds armed only with newfound courage. Egyptian youth leader and labor activist Ahmed Maher could have been speaking for the entire region when he declared in January 2011: “The people are no longer afraid. We want a democratic state that respects human rights and allows all its citizens to live in dignity.”

The display was enough to rattle China, which tightened its control of the Internet, local party bosses, and the foreign press corps. Russia’s Vladimir Putin clamped down so hard that he threw the punk band Pussy Riot in prison. In Saudi Arabia, the king spent billions in new handouts to quell revolutionary sentiment, while the dictatorship in Syria went for broke, torturing and shooting the first unarmed demonstrators and escalating to a consuming and murderous civil war.

Popular movements, in 2013, turned out to have less power than it had seemed, while authoritarian states emerged as crafty and resilient. In Egypt, after a brief experiment with an elected civilian president, chanting crowds demanded the installation of a new dictator, General Abdel Fattah el-Sissi; the activist Maher, meanwhile, is now in prison, sentenced to three years for protesting. Regimes in Iran and Syria regained their old swagger, while activists in Saudi Arabia and Algeria watched these outcomes and held back. The one bright spot in the Arab world was Tunisia, where elections have spawned coalition governments and where real change and compromise appear to be in the works.

After the crackdowns, the leaders of Russia and China today appear confident that no Internet activists or civil society groups can break their regimes’ monopoly of power. Egypt’s muscle-flexing new authoritarians, and Syria’s resurgent old ones, convincingly demonstrated that if the wind of people power is still blowing, it is far from an irresistible force.

Regional realignment with Hezbollah, Assad & Iran?

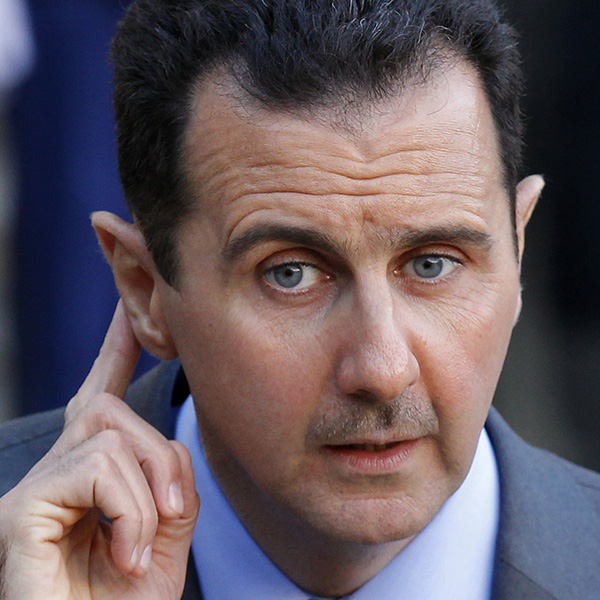

Hassan Laqqis, assassination scene. Source: Al Manar

There’s been lots of talk about the regional consequences of the Iran nuclear deal, and of a realignment as the West realizes that it might prefer Assad in power to a jihadi-dominated rebel government or some version of the current punishing settlement. Ryan Crocker told The New York Times that the US should resume cooperating with Damascus against Salafi jihadis, and various analysts and diplomats have been speculating that Iran, Assad, Hezbollah, and the US share plenty of common interests. Saudi Arabia and Israel stand to lose if the US begins to behave like a mature superpower, collaborating where it sees fit rather than holding itself hostage to the agenda of small allies behave as peers rather than clients.

The latest trigger was yesterday’s assassination of a Hezbollah official in Beirut. (Hassan Lakkis, according to Hezbollah’s Al-Manar Television, played an important role in the fight against Israel; Reuters reports that Lakkis was fighting recently in Syria.) That killing once again raised the question of Hezbollah’s broader direction. Has it provoked a maelstrom of jihadi attacks, retaliation for Hezbollah’s role in the Syrian civil war? Or is the conflict in Syria playing out in the interests of Hezbollah, Assad and Iran?

I think there’s some evidence that three years after a non-violent popular revolt against Assad’s nasty dictatorship, Assad has finally managed the shape the conflict he wanted. He wiped out the non-violent resistance, the intellectuals and the pluralists, and continues to mass his firepower against the FSA rather than the jihadists. As a result, the conflict pits an authoritarian but non-sectarian dictatorship against a Sunni rebellion dominated by takfiri jihadists. Hezbollah entered the war supposedly to fight the sectarian jihadis over there before they made it over here, a la George W Bush. It sounded facile then, but now it sounds true; each time there’s a bomb of assassination in Lebanon, it adds credence to Hezbollah’s claim that it’s on the side of a Middle Eastern order that tolerates multiple faiths and power-sharing, while on the other side Saudi and other Gulf money is supporting extremists who want to recreate the 7th Century Caliphate. Self-serving, but perhaps, true.

We’ve seen hints of change:

- An increase tempo of back-and-forth attacks in Lebanon.

- Stronger desire by Lebanese national institutions to contain the crisis.

- Reports that the US has shared intelligence with Lebanon in order to protect Hezbollah from attacks.

- A real push – in Track 2 and perhaps Track 1 diplomacy – to make the January talks in Geneva really amount to a negotiation for a settlement in Syria.

- The Iranian nuclear deal, which could calm anxieties about the regional Iran-Saudi cold/hot war, and allow for some tit-for-tat that could reduce global interest in the Syrian theater.

What should we look for as signals of a coming, substantive change?

- Rhetoric from Hassan Nasrallah that opens the door to a frigid détente with the US on some issues.

- Continuing restraint by Hezbollah in its response to attacks and assassinations.

- Agreements or accords that result from the vigorous outreach by Iran’s foreign minister to the leaders of the Arab countries in the Gulf.

- Offers, even totally rhetorical ones, from Assad to cooperate with the US against the jihadi groups in Syria.

The interim Iranian nuclear agreement could easily collapse (Marc Lynch writes here about the enormous potential but also the need to remember that it could all come to naught), but it’s a major opening. Iran has always been a more natural geopolitical ally for the US than the tiny oil-rich monarchies of the Arabian peninsula. It’s hard to imagine a full realignment without an internal shift in the governance of Iran, but perhaps, that could occur with a political shift short of regime change. The most likely outcome is incremental, with Iran and the US finding more avenues of cooperation but stopping short of an open embrace. But even the prospect of a cooling in the US relationship with absolute monarchs of the Gulf and the hawkish establishment of Israel, in favor of a more pragmatic policy that leaves room to cooperate with all the region’s heavyweights, has prompted a panic in Riyadh and Israel. That anxiety suggests it’s a very real prospect, and one that in the long-term would serve to cool down the region.

Is Dubai the future of cities?

AFP PHOTO/MARWAN NAAMANI/GETTY IMAGES

Burj Khalifa soars above the other buildings in Dubai.

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT, Lebanon — The Palestinian poet and filmmaker Hind Shoufani moved to Dubai for the same reasons that have attracted millions of other expatriates to the glitzy emirate. In 2009, after decades in the storied and mercurial Arab capital cities of Damascus and Beirut and a sojourn in New York, she wanted to live somewhere stable and cosmopolitan where she also could earn a living.

Five years later, she’s won a devoted following for the Poeticians, a Dubai spoken-word literary performance collective she founded. The group has created a vibrant subculture of writers, all of them expats.

To its critics—and even many of its fans—“culture” and “Dubai” barely belong in the same sentence. The city is perhaps the world’s most extreme example of a business-first, built-from-the-sand boomtown. But Shoufani and her fellow Poeticians have become a prime exhibit in a debate that has broken out with renewed vigor in the Arab world and among urban theorists worldwide: whether the gleaming boomtowns of the Gulf are finally establishing themselves as true cities with a sustainable economy and an authentic culture, and, in the process, creating a genuine new path for the Middle East.

KARIM SAHIB/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest tower.

This is a question of both economic interest and huge sentimental importance. The Arab world is already home to a series of capitals whose greatness reaches deep into antiquity. The urban fabric and dense ancient quarters of Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, and Beirut have long nourished Arab culture and politics. But, racked by insurrection, unemployment, and fading fortunes, they have also begun to seem, to many observers, more mired in the past than a template for the future.

The Dubai debate broke out again in October when Sultan Al Qassemi, a widely read gadfly and member of one of the United Arab Emirates’ ruling families, wrote a provocative essay arguing that the new Gulf cities, Dubai most notable among them, had once and for all eclipsed the ancient capitals as the “new centers of the Arab world.” A flurry ofwithering essays, newspaper articles, and denunciations followed. “I touched a sensitive nerve,” Al Qassemi said in an interview.

His critics object that Dubai is hardly a model—as they point out, 95 percent of the city’s population is not even naturalized, but made up of expatriates with limited rights. And there’s another problem as well. Every one of the Gulf boomtowns—besides Dubai, they include Abu Dhabi, Qatar, Manama, and Kuwait City—has been underwritten, directly or indirectly, by windfall oil profits that won’t last forever.

AMRO MARAGHI/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

A mosque in Cairo.

In her seminal work “Cities and the Wealth of Nations,” Jane Jacobs argued that cities that were a “monoculture” last only as long as the boom that created them, whether it involved bauxite, rubber plants, or oil. To thrive in the long term, cities need adaptable, productive economies with diverse, high-quality workers and enough capitalist free-for-all so that unsuccessful businesses fail and new ones spring up. Otherwise they risk the fate of single-industry cities like New Bedford, Detroit, or the completely abandoned onetime mining city at Hashima Island in Japan.

Can Dubai and its peers successfully make that transition? Started as the kind of monocultures that Jacobs argued are doomed to fail, they are now trying to harness their money and top-down management to create a broader web of interconnected industries in the cities and their surrounds.

Dubai is the cutting edge of this experiment. With its reserves depleted, its growth comes from a diverse, post-oil economy, although it still receives significant financial support from other Emirates that are still pumping petrochemicals. Its rulers are determined to make their city a center for culture and education, building museums and institutes, sponsoringfestivals and conferences, with the expectation that they can successfully promote an artistic ecosystem through the same methods that attracted new business. What happens next stands to tell us a lot about whether an artificial urban economy can be molded into one that is complex and sustainable. If it can, that may matter not just for the Middle East, but for cities everywhere.

***

JACOBS, A PIONEERING WRITER on cities and urban economics who died in 2006, is perhaps best known for “The Death and Life of the Great American City,” her paean to Greenwich Village and small-scale urban planning. But in her 1984 follow-up about the economies of cities and their surrounding hinterlands, Jacobs showed a harder nose for business. To be wealthy and dynamic, she argued, cities needed not to depend on military contracts or to be hampered by having to subsidize other, poorer territories—pitfalls that have driven the decline of many a capital city. In her book, she touted Boston and Tokyo as creative, diversified economic engines. But many of the world’s storied capital cities, like Istanbul and Paris, she wrote, were fatally bound to declining industries and poor, dependent provinces.

Today, that description perfectly encapsulates the burden carried by the Arab world’s great cities. Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo historically hosted multiple vibrant economic sectors: finance, research, manufacturing, design, and architecture. Eventually, though, they were hollowed out. Oil money, aid, and trade eliminated local industry, and the profits of these cities were siphoned away to support the poverty-stricken rural areas around them.

As these cities fell behind, a very different new urban model was rising nearby, along the Persian Gulf. As the caricature of the Gulf states goes, nomadic tribes unchanged for millennia suddenly found themselves enriched beyond belief when oil was discovered. The nouveaux riches cities of the Gulf were born of this encounter between the Bedouin and the global oil market.

The reality is more nuanced and interesting. The small emirates along the Gulf coast had long been trade entrepôts, and Dubai was among the most active. Its residents were renowned smugglers, with connections to Persia, the Arabian peninsula, and the Horn of Africa. When oil came, the Emirates already had a flourishing economy. And because their reserves were relatively small, they moved quickly to invest the petro-profits into other sectors that could keep them wealthy when the oil and gas ran out. Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Sharjah (all in the Emirates) pioneered this model, with neighboring Manama, Qatar, and Kuwait City following it closely.

Skeptics have decried the new Gulf cities, often vociferously, ever since the oil sheikhs announced their grand ambitions to build them in the 1970s. In his 1984 classic “Cities of Salt,” the great novelist Abdelrahman Munif chronicled the rise of the Arab monarchs in the Gulf. He explained the title to Tariq Ali in an interview: “Cities of salt means cities that offer no sustainable existence,” Munif said. “When the waters come in, the first waves will dissolve the salt and reduce these great glass cities to dust. With no means of livelihood they won’t survive.”

And yet, despite the apparent contempt of cultural elites, when civil war swept Lebanon, the Arab world’s financial center moved to the Gulf. Soon other sectors blossomed: light manufacturing, tourism, technology, eventually music and television production.

Dubai led the way. It built the infrastructure for business, and business quickly came. Over the decades, investment and workers flowed to a desert city of malls and gated communities, which had a huge airport, well-maintained streets, and clear rules of the road. Abu Dhabi, Manama, and Doha followed suit, although they took it more slowly; with continuing oil and gas revenue, they didn’t need to take the risk of growth as explosive as Dubai’s. Unlike the austere cities of Saudi Arabia, all the Gulf’s coastal trading cities had a tradition of a kind of tolerance. Other religions were welcome, and so were foreigners, so long as they didn’t question the absolute authority of the ruling family.

In the last four decades of the oil era, that model has evolved into the peculiar institution of a city-state dependent on a short-term foreign labor pool from top to bottom. The most extreme case is Dubai, where less than 5 percent of the 2 million people are citizens. Citizens form a minority in all the other Gulf cities as well. Wages for expatriates—especially workers in construction and service sectors like the airlines—are kept low, and foreign laborers are isolated from better-off city residents in labor camps. Construction workers who complain or try to unionize have been deported. White-collar residents who have criticized Emirati rulers or who have supported movements like the Muslim Brotherhood have had their contracts canceled or their residencies not renewed.

The economic crash of 2008 wiped out some of Dubai’s more excessive projects (although the signature underwater hotel finally opened this year). The real estate bubble burst; expats abandoned their fancy cars at the airport. “There was this glee that the city was over. But it was resilient,” said Yaser Elsheshtawy, a professor of architecture at the UAE University. The Gulf cities bounced back. Millions of new workers, from Asia, Europe, as well as the Arab world, have migrated to the Gulf since then.

“The Dubai model might be good, it might be bad, but it deserves to be looked at with respect,” Elsheshtawy said. Egyptian by birth, Elsheshtawy has lived on three continents, and he’s grown tired of having to defend his choice to work in the Emirates. After he read dozens of ripostes to Al Qassemi’s polemic, including many that he felt smacked of cultural snobbery toward anyone who lived in the “superficial” Gulf cities, Elsheshtawy penned an eloquent defense of Dubai called “Tribes with Cities” on his blog Dubaization. He doesn’t like everything about the Gulf, but Elsheshtawy believes that Dubai and the other booming Gulf cities, “unburdened by ancient history” and blessed by a mix of cultures, can provide the world “the blueprint for our urban future.”

***

DUBAI AND ABU DHABI, the showcase cities of the Emirates, often seem like a they’re run by a sci-fi chamber of commerce. They’ve got the world’s tallest building, the biggest new art collections in starchitect-designed museums, the busiest airports, and growing populations. Beneath that surface, though, lies a structure that worries even many supporters: Freedoms are tightly constrained, and most of the population is made of explicitly second-class noncitizens. Other growing cities chafe under censorship or political restrictions—Beijing, Hong Kong, and Singapore spring to mind. But there’s a difference between those places, where citizen-stakeholders live out their entire lifetimes, and a city where almost everyone is fundamentally a visitor.

Even Al Qassemi, the Emirati who believes the new cities have pioneered a better economic model, has argued that the citizenship restriction will hurt Dubai and cities that follow its model. “Without naturalization, all the Arabs who move here and are creating these cities will see them only as stepping stones to greener pastures,” Al Qassemi said. “People make money and they leave.”

There’s a glaring moral problem with a city ruled by a tiny clan where most of the workers have no rights. But the last few decades suggest that citizenship and political freedom aren’t prerequisites for GDP growth. Jacobs wrote a lot about what cities need, but the only kind of freedom she wrote about was the freedom to innovate and create wealth. The new Gulf cities have carefully provided a state-of-the-art, fairly enforced body of regulations for corporations—precisely the kind of rule of law they actively deny to foreign workers.

In treating businesses more solicitously than individuals, the Gulf city model may depend on a twist that Jacobs never foresaw: They don’t care whether people stick around. In fact, these new cities assume they will be able to innovate precisely because they won’t be encumbered by citizens whose skills are no longer needed. If Dubai needs fewer construction and more service workers, or fewer film producers and more computer programmers, it simply lets its existing contracts lapse and hires the people it needs on the global market. The churn isn’t a flaw in the model; it’s part of its foundation.

That may explain why even Dubai’s defenders are not planning to stick around. Shoufani, the poet, says she cherishes the secure space to create that Dubai has given her, but she still plans to move on in a few years. So does Elsheshtawy, the architecture professor whose academic studies of urban space have helped counter the narrative of Dubai as a joyless, dystopian city interested only in the pursuit of money. He plans to retire somewhere else. It may not matter to Dubai’s fortunes, however, as long as people arrive to take their place.

The next few years will begin to tell how this experiment has turned out. Just as Jane Jacobs said, it doesn’t matter so much how a city was born. It matters how its economy operates. If Dubai and its imitators outlive the oil revenues and regional instability that helped them boom, it will be a lesson for cities everywhere in how to invent a viable urban economy—even if it leads to a kind of city that Jacobs herself might have loathed to live in.

How much to worry in Lebanon, once more?

REUTERS PHOTO

After today’s bombing at the Iranian embassy in Beirut, how much should we worry that the war in Syria will engulf Lebanon? First, the usual caveat: I live here, and I have a vested interest Lebanon remaining viable and stable, so discount my analysis accordingly.

Nonetheless, nothing so far has changed my fundamental view that the major players in Lebanon want to preserve the existing order here, as combustible as it is. The attackers presumably come from the jihadist strain of the Syrian opposition; they have little invested in the Lebanese status quo and are willing to upend it. But the major actors with organizations in Lebanon, including the Sunnis who support the Syrian rebels, as well as the Hezbollah constituents who support the Syrian government, benefit from the truce in Lebanon. Beirut especially serves as a neutral area where all parties communicate with each other, raise funds, and do their political work.

Iran’s immediate accusation of Israel supports this view: if Iran wanted to raise tensions, it would point at jihadists or Lebanese factions allied with the Syrian opposition. Instead, it pointed at Israel (just like Hezbollah did after the Dahieh bombing in August), a convenient and unifying enemy. Blaming Israel is a calming gesture; even if Hezbollah and Iran suspect a local or Syrian Sunni network, it deflates tension to pin the attack on Israel. And if Iran genuinely has evidence or believes Israel is responsible, that’s all the better insofar as it minimizes the risk of hostilities taking root beyond Syria’s borders.

In coming weeks, we should watch the rhetoric of Hassan Nasrallah; if he repeats his previous positions on the Syrian war, as I expect, that will signify that Hezbollah maintains its interest in a calm Lebanon. We also should watch the retaliation; small attacks against centers of jihadist activity would remain with the limited framework that, again, minimizes the chance of escalation.

Today’s attack is certainly a worrisome development, since the apparent suicide bombers struck a diplomatic target. It will increase anxiety among all people in Lebanon, and will especially worry the civilians living in the Dahieh, who already suffered an indiscriminate attack in August that killed 20 people and wounded more than 100. These are not good things. But they don’t guarantee that war will engulf Lebanon either. For that to happen, the established parties here – in particular Hezbollah and the Future Movement – would have to radically change their cost-benefit analysis. So far, I don’t see that happening. Lebanon’s future holds more simmering violence, like the back and forth bombings, assassinations, and occasional skirmishes we’ve seen so far in the Bekaa, Tripoli and Beirut; but not, I expect, outright conflict.

What sprouted in the Arab revolts?

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT — Three years after the revolts of the Arab Spring, the reformers’ initial euphoria has given way in much of the region to weariness and even despair. Civil war has overtaken Syria; Egypt is under the thumb of a newly aggressive military junta. In Bahrain, the opposition is in disarray or detention, despite representing a clear majority of the people; Libyans haven’t managed to tame the patchwork of warlords that overthrew Moammar Khadafy. Just recently, the head of the Maronite church in Lebanon joined the pessimistic chorus by talking about an “Arab winter.”

In writings, private conversations, and political forums, many of the most committed partisans of the popular uprisings are starting to ask just what has changed. What, if anything, did the Arab revolts actually accomplish?

The full answer to that question lies perhaps a generation away. But surveying the scene, it is becoming increasingly clear that for all that hasn’t happened, at least one positive change has survived and taken root: a vigorous and healthy new version of civil society.

In one nation after another, Arab citizens have come together into organized independent groups, keeping their distance from the state, even actively criticizing regimes and braving jail time. Egyptian collectives have arisen to document state torture and capricious detention; bootstrap Syrian aid organizations smuggle in supplies to run clinics and refugee processing centers. Bahrainis are agitating for political reform, and new groups in Yemen are trying to ensure reform follows regime change there. Tunisia’s notable successes have come alongside a flourishing of labor, media, and cultural groups.

A woman drove a car in Saudi Arabia on October 22. REUTERS/FAISAL AL NASSER

“Organizations are the most important thing we made in the uprisings,” said Moaz Abdel Kareem, an Egyptian activist who has helped found half a dozen, including a political party and citizens forum.

As these civic groups deepen their roots, they could prove genuinely transformative. The autocrats that ruled Arab societies could do it only because they had systematically suppressed independent civic life for so long. And collectively, the very fact that these new groups survive and thrive is evidence of something bigger taking place across the region: a meaningful new understanding of what it means to be a citizen and live in a state.

The groups are still fragile, and their success in no way guaranteed. But even with the old regimes still largely holding their political power, they represent a meaningful ray of hope. And to see the ways in which they have sprouted in one country after another is to appreciate just how broadly this new thinking has touched the Arab world.

***

IN MUCH OF THE WORLD, civic organizations are taken for granted: They play roles from the local, like running shelters for the homeless, to the national, like crafting and lobbying for transformative new laws. The Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded 22 times to civic groups rather than individuals—the first time in 1904, to the Institute of International Law. Where they exist, they testify to an empowered citizenry—and to a deeper social contract in which the state’s powers extend only so far.

Such groups are anathema to totalitarian regimes, and accordingly the autocrats of the Arab world staved off meaningful challenges by corralling and neutering civic organizations for much of the 20th century. Independent political parties were outlawed. The media swarmed with censors and intelligence agents planted by the state; even religious clerics were vetted. Syndicates and labor unions, religious organizations, welfare for the poor, women’s societies—none fell far from government control. Any remotely political-sounding civic activities—which in some cases extended to acts like delivering food to the poor or holding training workshops for women—were often simply criminalized.

In the past, some Arab states witnessed brief flare-ups of civic activity. One happened in Syria in 2000; another in Egypt in 2005-06. But those were cases of brief openings, allowed by the state, and then quickly and thoroughly shut down.

MOSIREEN The Egyptian video collective Mosireen, which began as a group of videographers and filmmakers documenting the Tahrir Square uprising in January 2011, has survived and grown into an archive and distribution system explicitly challenging government propaganda.

Born in the 2011 revolts was something new. Partly galvanized by the genuine hope of change, partly because states had sunk to new lows in disregard for their citizens, and partly because of social networking, citizens began to coalesce into meaningful organizations. They often started very loosely—like the Egyptian Facebook group that protested the police murder of Khaled Said in 2010, or the online chat groups that discussed the potential presidential candidacy of Mohamed ElBaradei. But as the revolts gathered steam, so did the civic groups. The Khaled Said group organized small protests, then large ones, eventually attracting hundreds of thousands of citizens to risk their safety in the dangerous street actions that helped bring down the regime. ElBaradei’s Facebook fans eventually founded the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, which has emerged as a key political player.

Today, that immediate revolutionary fervor has mostly subsided, but many of the organizations founded at its peak are still hard at work in Egypt and elsewhere, steering what little political debate survived the resurgence of the old power structures.

The most basic, and widespread, are service organizations. In Syria, for example, the embattled Assad regime has grudgingly allowed citizens to form solidarity and aid groups. In rebel-controlled areas, militia leaders have to share power with civilian coordinating committees. Vast new civilian aid networks have formed to serve the 2 million Syrian refugees and the 4 million more people who have been displaced within the country’s borders. Their work isn’t overtly political—securing housing, health care, and education—but their independence and resilience are new in Syria. Until now it’s been a crime for Syrians to form even a chamber music company without government permission.

The overtly political groups have had even more impact. In Bahrain, for example, where the regime cracked down on popular protests hard enough to marginalize its opposition, the 11-year-old Bahrain Center for Human Rights has established itself as one of the most important de facto political forces in the nation. As the three-year-long struggle simmers between the Shia majority population and the Sunni minority royal family, the small human rights nongovernmental organization has provided consistent evidence of sectarian discrimination and government torture, rallying Bahrainis and alerting the outside world. It is essentially a new element in society: an independent group that endorses equal rights under the law, eschewing both clerical oversight and government control.

A Bahraini human-rights center has emerged as a key political voice. MOHAMMED AL-SHAIKH/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Traditionally the political leader of the Arab world, Egypt has seen an even more impressive array of groups emerge, built on a broad but tenuous community of activists that had weathered the Mubarak decades. The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights has unnerved authorities by simply documenting government actions, like prosecutions of journalists for critical speech or harassment of civic groups for receiving foreign funds. The No to Military Trials campaign tracks the number of civilians brought before military tribunals, helps them find representation, and campaigns to turn Egyptian attitudes against the practice. The Egyptian video collective Mosireen, which began as a group of videographers and filmmakers documenting the Tahrir Square uprising in January 2011, has survived and grown into an archive and distribution system explicitly challenging government propaganda. (Disclosure: I contributed to Mosireen’s Kickstarter campaign this year).

Even Saudi Arabia, seemingly the most change-proof of the Arab states, has seen an uptick of the kind of sustained pressure that only mature civil society can produce. Women fighting for their right to drive have in the last month begun a civil disobedience campaign, posting online videos of themselves driving and calling for a nationwide drive, all in hopes of forcing a change in the kingdom’s restrictive law.

***

WHEN I CANVASSEDa dozen activists across the region about the legacy of the revolts today, many of them bemoaned the current strength of military rulers in Egypt and Syria, and the triumphalism of conservative, cash-rich monarchs in the Gulf. But they all returned to the idea that a psychological threshold was crossed when once-passive citizens decided they could control their political fates.

“The Arab uprisings, particularly Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, seem to have done away with that haunting sense of powerlessness, of impotence, that was the badge of the ‘Arab malaise,’” wrote Farah Dakhlallah and Adam Coutts in an essay published in the 2012 book “Scepticism: Hero and Villain.”

This has not come easily. In the Arab uprisings, activists—most of them young and relatively unseasoned—have undertaken the gargantuan task of conjuring these new civic institutions from scratch. And over the last three years, they’ve suffered attacks from many directions—from Islamists with their own agenda for the future; from secular regimes; at times from vituperative nationalist public opinion. Dictators have succeeded before in squelching independent civic groups, and in co-opting any that survive.

Nonetheless, there’s reason to see this change as the foundation of a different kind of future. The iconic chant across the region, from the start of the protests in Tunisia and Egypt, demanded the fall of the “nidham,” which translates as “regime,” but also as “system.” People knew their problems weren’t just with a ruler, but with a whole web of control. Healthy states depend on checks and balances, and civic groups matter deeply to their emergence. Think of Solidarity in Poland, Mandela’s African National Congress, or Otpor in Serbia; these were popular civic groups that became the seeds of a new system. In political science, study after study shows that a dynamic and independent civil society plays a determinative role in transitions to democracy.

The flowering and maturation of Arab civil groups might feel slow to the crowds flashing cellphone messages to each other three years ago, and less dramatic than the call for the head of one dictator or another. But it may be the only work that ultimately can replace the epic abuses of the Arab authoritarian states with a new culture of citizenship and law.

Egyptian activist Abdelrahman Ayyash, in an interview from exile in Turkey, said he and many of his colleagues had been discouraged by the violent crackdown that has accompanied the rebounding fortunes of the old ruling class in Egypt, Syria, and elsewhere. But he also took encouragement from the spirit he had felt arising among his fellow citizens. “Even if we are down right now, we have changed,” he said. “All of us.”

A new brain trust for the Middle East

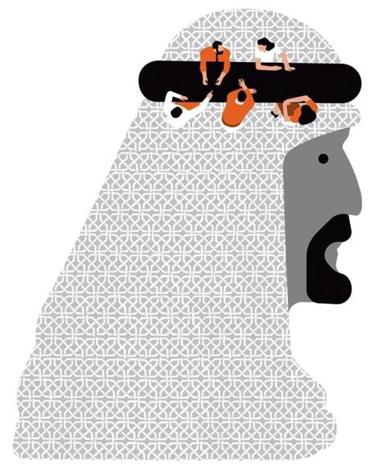

PABLO AMARGO FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT—In any American university, what the six researchers in this room are doing would be totally unremarkable: launching a new project to use the tools of social science to solve urgent problems in their home countries.

But for the young Arab Council for the Social Sciences, this work is anything but routine. The group’s fall meeting, initially planned for Cairo, was canceled at the last minute when Egyptian state security agents demanded a list of participants and research questions. The group relocated its meeting to Beirut, meaning some researchers couldn’t come because of visa problems. Still others feared traveling to Lebanon during a week when the United States was considering air strikes against neighboring Syria. Ultimately, the team met in an out-of-the-way hotel, with one participant joining via Skype.

Their first, impromptu agenda item: whether any Arab country could host their future meetings without any political or security risk.

The council’s struggle reflects, in microcosm, a much bigger problem facing the Middle East. With old regimes overthrown or tottering, for the first time in generations a spirit of optimism about change has swept through the region. The Arab uprisings cracked open the door to new ideas for how a modern Arab nation should govern itself—how it could rebalance authority and freedom, religious tradition and civil rights. But a key source of those new ideas is almost completely shut off. With few exceptions, universities and think tanks have been yoked under tight state control for decades. Military and intelligence officials closely monitor research, fearing subversion from political scientists, historians, anthropologists, and other scholars whose work might challenge official narratives and government power.

Just one year after its launch, the ACSS is hoping to fill that vacuum, giving backing and support to scholars who want to do independent, even critical thinking on the problems their societies face. It’s a daunting order in a region where for generations talented scholars have routinely fled abroad, mostly to Europe and North America.

“There’s been almost a criminalization of research here,” says Seteney Shami, the Jordanian-born, American-trained anthropologist tapped to get the new council running. “We want to change the way people think about the region.”

It took nearly five years of planning, but the new council is now finishing its first year of operation. It has awarded roughly $500,000 to 50 researchers. Its goal is ambitious: to build an enduring network that will connect individual researchers who until now have mostly labored alone, under censorship, or overseas. The council aims to give those thinkers institutional punch—not just funding for projects that aren’t popular with local regimes or Western universities, but muscle to fight authorities who still maneuver to block even the most innocuous-sounding research missions. Today issues of ethnic, sectarian, and sexual identity are still taboo for governments—and they’re precisely the focus for most of the researchers who met in Beirut.

Shami and the other founders envision the council as only a first step, helping push for new openness in universities and in publishing. Ultimately, they believe, it stands to change not only how Arab countries are perceived abroad, but the way those countries are governed. Given the incredible turbulence in the Arab world today, it’s easy to see why a new flowering of social science is needed—and also why it’s a risky proposition for whoever hopes to set it in motion.

***

WHEN WE THINK about where ideas come from, we often picture lone thinkers toiling indefatigably until they achieve their “eureka” moments. But in fact, the ideas that change the way we organize or understand our daily world grow most readily from ecosystems that can train such scholars, test their claims, and ultimately spread and promote their new thinking. The modern West takes this system for granted; universities are perhaps the most important nodes in a network that also includes foundations, think tanks, and relatively hands-off government funding agencies.

Even societies like China, with its tradition of centralized state control, support a vigorous web of universities and institutes that produce and test ideas. In China, the government might drive the research agenda—rural educational outcomes, say, or international trade negotiations—but researchers are expected to produce rigorous results that stand up to outside scrutiny.

Not so in the Arab world. Despite a historic scholarly tradition, and a vigorous cohort of contemporary thinkers, the intellectual institutions in Arab countries are today almost universally subordinated to state control. As the dictators of the 1950s matured and grew stronger, they feared—correctly—that universities would nurture political dissent and that students were susceptible to free-thinking. (Even today, groups like the Muslim Brotherhood induct most of their leaders into politics through university student unions.) So they dispatched intelligence officers to control what professors taught, researched, and published, and to curtail student activism of a political flavor.

To the extent that think tanks, institutes, and journals were allowed to exist at all, they became either government mouthpieces or patronage sinecures. Plenty of individual scholars have continued to work in an independent vein, and many do research or publish work outside the influence of the ruling regime. For the most part, though, they do so abroad; those who speak openly in their home countries have often encountered gross repression, like the Egyptian sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim, an establishment thinker who was imprisoned in 2000 for taking foreign grant money. His prosecution—despite his close ties to the ruling dictator’s family— served as a reminder to other scholars not to stray too far from the state’s goals.

The obstacles to researchers who hope to confront the region’s problems run even deeper than that: in most Arab nations, even basic data on public issues like water consumption, childhood education, and women’s health are treated as state secrets. So are government budgets, and anything to do with the military, the police, and industry. Egypt still tightly guards access to land registries running as far back as the Ottoman Era; Lebanon famously hasn’t conducted a census since 1932, and refuses to release any government data about the population size or its religious composition. International agencies like the World Bank are allowed to conduct surveys and research as part of development aid projects, but only on the condition that they keep the data confidential.

As a result, great Arab capitals like Damascus, Beirut, Baghdad, and Cairo, once among the world’s great centers of learning, have suffered a systematic impoverishment of intellectual life, especially in the realms in which it is now most needed.

***