The Broken Dream of Tahrir Square

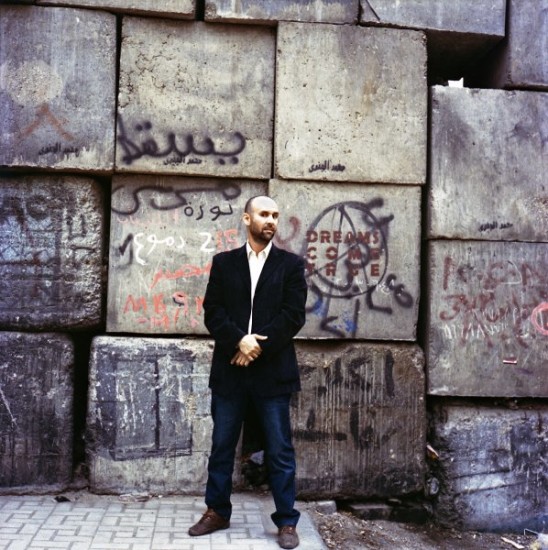

Basem Kamel in Cairo. Photo: Rena Effendi/Institut/DER SPIEGEL

[Der Spiegel published this update on a trio of revolutionaries four years after Tahrir Square. I extended the reporting for Once Upon a Revolution with followups in Cairo and Istanbul this winter. The story has been translated from English into German and then back again.]

On the fourth anniversary of the revolution, jailed blogger Alaa Abdel Fattah weighs 72 kilograms (159 pounds). It’s the 84th day of his hunger strike. Former Muslim Brother Moaz Abdelkarim has fled to Turkey. And architect Basem Kamel plans on running for parliament this spring.

For 18 days, the three men served as the protagonists in a grand historical drama. They wanted to reinvent their country and indeed the entire Middle East, with the world looking on enthusiastically. Without these three men — a Muslim Brother, an architect and a blogger who represent the heart, soul and brawn of the insurgency — the Egyptian revolution might never have happened.

The three activists camped out almost every day on Tahrir Square, helping the wounded and coordinating the protests. When Hosni Mubarak announced his resignation on Feb. 11, 2011, millions in Tahrir — and across the country — screamed, prayed and danced. “Never again can the regime ignore the people,” architect Basem said, barely audible over the euphoric chanting. He was confident that the generals who had seized power in Mubarak’s wake would be quickly dispatched by people power.

But four years later, there is little left of the revolution — its heroes have either fled, been jailed or receded into insignificance. Despite all this, they still haven’t given up.

Fleeting Freedom

When the Tahrir uprising began, Alaa Abdel Fattah was in South Africa, where he’d moved to take a computer programming job. He quickly returned, and when I first met him in February 2011, he was staring wistfully at the state media headquarters, the Maspero Building on the Nile River. “It’s impossible to take over this building,” he said, pointing at the row of tanks protecting it from the thousands of young unarmed demonstrators out front. “They could kill us all.”

Fattah was 29 at the time. He had a potbelly, long curly hair and a smile that pushed out his cheeks. He dressed like a programmer and brought brainy discourse to Tahrir, but he was also equally committed to the fight, standing firm in the face of regime attacks. His father was a well-known human rights lawyer and Abdel Fattah seemed to be born with the spirit of resistance in his blood.

Hosni Mubarak was still in power the first time he got sent to jail. The second came after the revolution in 2011. He got hauled in for a third time at the end of 2013. A fourth arrest occurred during the summer of 2014. On August 18, 2014, Abdel Fattah began a hunger strike in his prison cell.

At Abdel Fattah’s trial in September, the absurdity of the paranoid police state was on full display. He stood accused of crimes against the state and was sentenced to 15 years in jail. The defendant was put in a glass cage, his microphone silenced. Prosecutors, clearly unable to prove that Abdel Fattah committed any crimes against the state, showed a video illegally seized during his arrest. It showed his wife belly dancing at a private gathering. He was released on bail, but only briefly.

“My temporary release is a conspiracy like the case with my imprisonment,” Abdel Fattah wrote on Facebook after he got let out of jail. He was arrested again only a few weeks later. The conviction has since been overturned due to procedural errors, but he remains in prison awaiting retrial. Abdel Fattah’s younger sister, Sanaa Seif, is also in jail, serving out a two-year sentence for protesting her brother’s detention.

This is the situation in Egypt today, four years after the revolution, which began on Jan. 25, 2011 and ultimately forced the resignation of Hosni Mubarak, who had been the country’s president for decades. After the military unseated Muslim Brother Mohammed Morsi as the country’s first elected civilian president in July 2013, the brief phase of freedom came to an abrupt end. In the time that has passed since, the Muslim Brotherhood has been outlawed. Court proceedings against Mubarak didn’t lead anywhere; and his sons, who also faced charges, have just been released from jail. Meanwhile, most of the influential revolutionary activists are either in jail or have fled into exile abroad. In Cairo, the military is ruling again with a strongman at its helm.

Today there are even fewer avenues for dissent than there were before the revolution. No public gatherings are allowed; the secret police exerts a tighter grip than ever; parliament has been disbanded; and the media cheers on President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

Moaz Abdelkarim in Istanbul.

A Failed Revolution

There are also court proceedings against Moaz Abdelkarim in Cairo, but he managed to flee the country in time. The pharmacist and former Muslim Brother now lives in Istanbul and has shaved his light beard. “It doesn’t look like a revolution,” he says. “It looks like a failure.”

During the revolution, Abdelkarim was a young Muslim Brother who dressed like an old Islamist, with pleated pants and plaid shirts. He had a youthful grin and was a bit naive, but he also had an iron rebellious streak. He had grown up inside the disciplined Islamist movement as a third-generation Muslim Brother, but he chafed at its dictatorial traditions. Brotherhood leaders ordered their members to stay away from the uprising, but Abdelkarim ignored them, instead joining a group of opposition activists who met in secret apartments and later formed the seeds of the Revolutionary Youth Coalition.

After the revolution, Abdelkarim and other young Muslim Brothers formed the new Egyptian Current party. They were Islamists, but they believed passionately in a liberal, secular government and were committed to democratic principles and separation of religion and state. “I am Islamic,” he said in the spring of 2011. “But I don’t want an Islamic state. A state can’t be Islamic any more than a chair can be Islamic.” He attacked the Muslim Brotherhood in public when its members decided to found a party. The organizers responded by initiating disciplinary proceedings against Abdelkarim and expelling him.

On two different occasions, the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces invited Revolutionary Youth Coalition leaders to meetings, and Abdelkarim also attended. The bemused generals listened to what the young activists had to say, but then politely ignored all their proposals and appeals. It quickly became clear to Abdelkarim that the generals had no intention of changing anything and that the old regime was still in power.

He nevertheless still believed the revolution stood a chance right up until the point when security forces invaded the Islamist encampment at Rabaa al-Adawiya Square on August 14, 2013. Supporters of Morsi had camped out and called for the reinstatement of their president. The security forces could have dispersed the sit-in with teargas and water cannons as they had done so often. But this time, they came in with guns blazing with live ammunition, at point blank range. The massacre lasted almost a day and, in the end, at least 800 people died — perhaps as many as 2,600, according to the Muslim Brotherhood’s estimates.

On Twitter, his friend Basem Kamel placed the blame for the massacre on Muslim Brotherhood leaders for putting their followers on a path to confrontation.

Abdelkarim drove the injured to the hospital, organized clandestine meetings and joined the team that lined the bloody corpses in a mosque, including those of many of his friends. One man bled to death in the backseat of his car. Exhausted, he cried as he drove. Abdelkarim lived out of his car for five days. He saw how friends who had survived were arrested within days of the massacre. The justice system also prepared cases against him, including the charge that he allegedly plotted together with the Lebanese Shia militant group Hezbollah.

When he returned home five days after the massacre, his mother cried. She thought he had died. He packed his things and boarded a plane to Turkey shortly thereafter.

For months, the state media covered nothing except “Islamist terror.” In November, three months after the massacre, the regime imposed severe restrictions on protests and arrested numerous critics under the pretense they represented a threat to national security. Blogger Abdel Fattah also ended up in jail again. In January 2014, el-Sisi tested the waters with a constitutional referendum that passed with 98 percent support. In May, he ran for president and won 97 percent of the vote.

Moaz Abdelkarim has since lived in Turkey, but he has to leave every 30 days in order to obtain a new tourist visa. His life is adrift in exile, and he is constantly on the go. Given that the trial against him is continuing, with charges that include terrorism, it’s possible he will never be able to return to Egypt. “They want to keep us busy with made-up cases so we have no time to fight the regime,” he says.

‘The Revolution Will End Like it Began’

These days, he’s focusing his efforts on reconciliation between secularists and Islamists that can serve as the basis for the start of the next revolution. He does this because he believes Egyptians will soon grow tired of el-Sisi’s rule. But on this wintry night, another of his mediation efforts between secularist government critics and Muslim Brothers in exile hasn’t gotten anywhere. The mistrust between them is so great that the two sides won’t even meet face to face.

“We need to start a dialogue and agree on things we can fight for,” Abdelkarim says. The only success story in the Arab spring came in Tunisia, where secular and Islamist activists had already engaged in dialogue in exile. He’s now trying to do that himself as a member of the leadership board of the small but well-known Al Ghad Al Thawra Party, one of the only secular parties to maintain cordial relations with the Muslim Brotherhood. But the party’s leaders are scattered in exile and are powerless against the regime’s propaganda. Abdelkarim studies Turkish and is toying with the idea of returning to work as a pharmacist. If he does, it’s likely he’ll be making a final break from politics.

Of the three revolutionaries, Basem Kamel is the only who is still able to participate in Egyptian political life without fear. After the revolution, he helped found the Social Democratic Party. He was one of only four Tahrir activists who got elected to parliament three years ago — a day he celebrated by changing his profession on Facebook from “architect” to “politician”.

When the newly elected parliament met shortly before the first anniversary of the uprising, Downtown Cairo looked like a war zone. The military had sealed the roads around Tahrir with concrete walls, and barbed wire marked the path to parliament. The Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists had secured a majority, but Kamel remained optimistic. “Revolution, finally, is politics,” he told me as he walked to the parliament.

At the same time, Moaz Abdelkarim was protesting outside against torture, arbitrary arrests and censorship that should no longer have been taking place. “The revolution will end like it began, with the same tiny group,” Abdelkarim said, standing before a wall of masked police. “A few hundred people will protest and nobody will pay attention.”

Kamel was one of the last to join the activists and he was older than most. He was 41 years old at the time — a tall, thin, balding man and father of three. His grandparents had been poor farmers, and he himself had studied architecture. During his university studies, he designed modern buildings using sustainable materials. But he earned his money with cheap cement block apartments that could cram in as many residents as possible. It helped him to rise to middle-class respectability in a tower on Cairo’s humble outskirts. But even toiling for 16 hours a day as he did, his family still had a hard time making ends meet. It angered him, and it was this anger that drove him — first to meet with Mohammed al-Baradei and soon afterwards to Tahrir.

The End of Democracy

The politicization of people like Kamel, who had studiously avoided politics for most of their lives, was one of the great achievements of the revolution at Tahrir Square. In that sense, he represents all Egyptians who otherwise would have preferred to hold back. Their support proved to be decisive in the revolution’s success. Ultimately, however, they were also the first to defect and support the military government.

“Aren’t you concerned about military rule?” I asked him after the generals toppled Muslim Brother Morsi in the summer of 2013.

“We know how to deal with the military,” Kamel said. “It’s the Islamists we’re worried about.”

Even though he had spent three years of his life fighting authoritarianism, he was buoyed by the end of democracy in Egypt. “It’s a revolution, not a coup,” he told me. “If you insist on calling it a coup, it’s a popularly legitimate coup.”

It’s still possible to meet with Kamel today at his Social Democratic Party headquarters, located in an imposing but rundown building in Downtown Cairo. It used to be teeming with people and energy, but today it is nearly empty. He says most Egyptians no longer support the party. “The problem in Egypt now is not the regimes,” he explains. “It is the people. We have to convince them.”

Even a year later, he still doesn’t regret that Morsi got ousted. What he does rue, however, is the return of a full-blown dictatorship in Egypt. “Today there is only one kind of politics allowed: Sisi’s politics,” he says. He believes el-Sisi will serve at least two terms as president. “Then we’ll be back in the game.”

Despite everything — including the fact that he lost his own position in the revolutionary parliament after it was dissolved in 2012 — he still wants to run again in parliamentary elections planned for this spring, even if 80 percent of the seats are reserved for independent individual candidates and only 20 percent are for the parties. That weakens the parties and strengthens those who are well-connected politically and can raise money for expensive campaigns.

Kamel is still convinced that Egypt can become a democracy, even if it takes decades for that to happen. He also believes it was the egomania of politicians and public apathy that doomed the revolution. He argues that the opposition parties should merge in order to increase their influence, but instead they are battling each other. All the parties founded after the revolution, he says with a sigh, are going the way of the ineffectual opposition parties that limped through the Mubarak years.

Kamel now wants to place more of a focus on his architecture business, which he neglected in recent years. He has lost his customer base and now his family is struggling to get by. “Today, my first priority is business,” he says. “Politics comes second.”

Alaa Abdel Fattah. Photo: DPA

‘We’re Fed Up’

Meanwhile, Alaa Abdel Fattah remains on a hunger strike and has just been taken to the prison hospital. Many activists have joined him in fasting. But so far, their joint action hasn’t done much to change things. It’s a last act of protest, a symbol of the dead-end road the revolution is heading in.

“What’s important now is that we organize ourselves and pressure the authorities that conspire against us,” Abdel Fattah said before he stopped eating. “I will not play the role they have written for me. We’re fed up.”

Alaa Abdel Fattah on this moment of suspended hope

Alaa Abdel Fattah has been one of the most interesting thinkers and actors of the Egyptian revolution. He knows politics, history and street activism, and he’s put his body and his mind fully into the struggle against authoritarianism for his entire life. He’s not always right, but he never has stopped thinking strategically and philosophically about the revolution, with a sincere willingness to admit mistakes and learn from them. He’s done so at every juncture in good faith and with an unerring moral compass. (I think along with Amr Hamzawy he’s been unique in trying to think in historical-political terms while also partaking directly in the struggle.) Fresh out of prison, he talked to Sherif Abdel Kouddous on Democracy Now! yesterday. The whole hour is worth listening to, but I was drawn to Alaa’s final comments about why he uses the word “defeat”:

But for it to be a revolution, you have to have a narrative that brings all the different forms of resistance together, and you have to have hope. You know, you have to be—it has to be that people are mobilizing, not out of desperation, but out of a clear sense that something other than this life of despair is possible. And that’s, right now, a tough one, so that’s why right now I talk about defeat. I talk about defeat because I cannot even express hope anymore, but hopefully that’s temporary.