The perils of elected strongmen

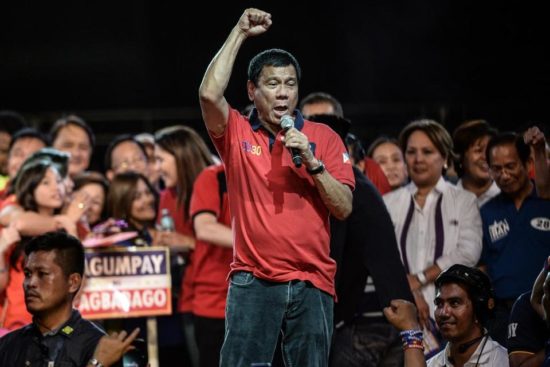

Rodrigo Duterte speaks to supporters during a campaign rally. MOHD RASFAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

FORCEFUL, FOUL-MOUTHED, and willing, by his own account, to try any policy that worked, Rodrigo Duterte seemed like a new kind of politician when he swept to power by a decisive margin in the Philippines last year.

Today, his brash, often toxic, approach offers an early look at a leadership style suddenly more in vogue, with Donald Trump’s victory in the United States and a crop of populist authoritarians waiting in the wings in democracies around the world.

There are differences between the budding strongman in Philippines and his peers in other countries. Duterte hails from a left-wing background and has decades of government experience as mayor of a provincial city. His thirst for power does not seem to be matched by a propensity for personal corruption.

Still, Duterte’s recipe holds some alarming lessons about what can happen when an authoritarian wins a democratic election and rules with contempt for the rule of law — but with the blessing of passionate popular support.

Duterte is willing to attack shibboleths and savage his critics. He’s trashed the media and suggested that his most outspoken Senate critic kill herself. He approaches running a nation of 100 million people like a bigger version of being a mayor for whom there’s no coequal branch of government. However much these tactics endear him to voters who are fed up with conventional politics, they also erode the unwritten political norms that make a democracy work.

Duterte’s brief but already searing record in office demonstrates how quickly an elected leader can undermine the institutions of democracy and begin to transform a state. It also shows that, when aspiring leaders make extreme promises, we should take them at their word. We should pay attention to the devoted crowds who applaud them, and we should take seriously the threat they pose to democracy.

IT WAS ONLY AFTER its “people power” revolution in the late 1980s that the Philippines became a modern democracy — after a bloody century that included some genuinely contested elections but also decades of dictatorship and a lengthy American military occupation. The democratic experiment has been shaky but also pathbreaking.

The nonviolent popular movement that overthrew dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1986 presaged the European revolts that brought down the Iron Curtain a few years later. For years the lone democracy in Southeast Asia, the Philippines provided moral and sometimes practical support for liberalism and pluralism elsewhere in the region. With no-holds-barred politics and a large population, the Philippines showed that even a rowdy and flawed democracy could stand in the way of authoritarian rule.

For a time, the Philippines looked like a promising regional barometer. By 2009 neighboring Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and East Timor had followed its lead, scoring as “free” or “partly free” by Freedom House.

Once again, the Philippines seems to be leading a political trend — this one not so positive. Democracy and reforms have regressed in Thailand and Malaysia, and Duterte ran a fiery campaign as much against the inefficiencies of democracy as against his opponents.

Fledgling democracies have not instantly solved poverty, crime, and other problems left over from decades of authoritarianism. Some countries whose democratic transitions have fared better, like South Korea, pair stable politics with rising levels of prosperity and development. But the theory that democracy and national wealth grow in tandem — popular among some political scientists — has been contradicted not only by the success of democracy in India, despite continuing poverty, but also by the surge in authoritarian politics in rich Eastern European countries and, now, America.

Duterte tapped into specific grievances about corruption, crime, and drugs, but also into a wider global malaise about the methodical approach to government that so many countries have pursued. He sold himself as a rough-talking straight-shooter, unconcerned about the feelings of a political establishment he viewed as self-serving and corrupt.

He won the May elections handily, 15 percentage points ahead of his nearest competitor. Crude comments about rape and an open contempt for civil liberties appeared to only help his campaign. Soon after his June 30 inauguration, Duterte shook things up at every level. He called President Obama a “son of a bitch” and the pope a “son of a whore. (He later apologized for the latter comment, which provoked outrage in the overwhelmingly Catholic Philippines.)

He also inaugurated a war on drugs in which he swore to kill or lock up every drug dealer and user in the country. He ordered the national police to pursue suspects with a vengeance. Of the roughly 7,000 people killed in this brief but bloody war on drugs, about two-thirds were killed by unknown gunmen.

“What President Duterte calls a war on drugs, in essence, has been a war on the poor,” said Rawya Rageh, is a senior crisis adviser at Amnesty International. “This wave of extrajudicial executions targeting people suspected of using or selling drugs appears deliberate, widespread, and systematic and may amount to crimes against humanity.”

Amnesty and local human rights groups say that Duterte tolerates no dissent. He has threatened to reimpose a state of emergency, a hallmark of the Marcos dictatorship. Duterte has bullied domestic critics in the Legislature, the media, and the human rights sphere.

Nightly shootings and mass arrests have become a signature of Duterte’s war on drugs, about which he is unapologetic. Upward of 100,000 people have been taken into custody. He revels in rumors that as mayor of Mindanao he killed drug suspects himself.

Philippine voters have responded with fear and awe. Malcolm Cook, a senior fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore and expert on the Philippines, said surveys show about 80 percent support the war on drugs, but an equal number fear they will be personally victimized by it. “What makes him different is that he is such a maverick and attacking so many assumed norms of Philippine politics,” Cook said. “There is no sign that he is paying a political cost. After six months in office, his popularity ratings are very high.”

Meanwhile, Duterte’s foreign policy shifts demonstrate the impact a purposeful leader can have. For years, Southeast Asian countries, working closely with the United States, tried to check Chinese expansion in the strategic South China Sea. But Duterte made clear that he didn’t care for the ironclad military alliance with the United States and would be willing to overturn decades of regional orthodoxy to forge a new deal with Beijing over the South China Sea, one of the most dangerous flashpoints in the world.

In October, a few months after he took office and before he knew who would succeed Obama, Duterte announced his “separation from the United States” at a shock press conference in Beijing. “America has lost now,” Duterte declared, pledging to be “dependent” on China. Duterte’s sudden shift threw the regional balance into disarray. And that was before Trump was elected and promised to undo Obama’s pivot to Asia and conciliatory approach to China.

CONVENTIONAL POLITICIANS considered such abrupt moves inconceivable in democratic nations. Yes, strongmen could maneuver wildly in countries where public opinion can be suppressed or managed. But over time, governments as fundamentally different as China, the European Union, and the United States adopted a bland, nonconfrontational approach to global politics. Even when the effort to downplay conflict was superficial, it reinforced the idea that a growing global community of nations respected the same taboos.

But Duterte, like Trump, has thrived while radically reorienting long-settled policies. In the Philippines, a strategic divorce from America was unthinkable a year ago, but now it’s underway. Similarly, the White House has shifted America’s approach to Russia, and many voters don’t appear to mind.

How long can pluralism survive Duterte’s kind of rule? Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, said that the Philippine president’s most controversial moves, like his violent drug war and coarse talk, fit in with regional norms, but the most important danger comes from Duterte’s threat against democracy itself. “This is a fragile democracy,” Kurlantzick said. “We should worry.”

The Philippines, Kurlantzick said, has one of the strongest executive presidencies in the world, similar to France’s. When a member of the supreme court hinted that Duterte’s drug war could eventually face judicial review, Duterte immediately raised the prospect of martial law.

“It’s very much like Trump acting as CEO of his family business,” said Cook, the Philippines expert. “He seems to think that as president, he has power over everything.” The joke in the Philippines during the US election, Cook says, was, “If you want to see what will happen when Trump wins, just look at us!”

Donald Trump developed his own persona over a lifetime in New York, but the echoes with Duterte are uncanny. In one of his first calls to a foreign leader, Trump supposedly praised Duterte’s drug war and according to Duterte, said he looked forward to meeting Duterte and getting advice about how to deal with BS (Duterte didn’t use the abbreviation). The only readout came from the Philippines, but no one in Trump’s camp disputed the account.

Back when Rodrigo Duterte was elected president of the Philippines, his type seemed almost comic — a bit scary, but on the fringe. Today, he shows how a chauvinist can rise to power not in backwater coups or in countries like Egypt that were authoritarian to begin with, but in free elections.

For some time, the United States, too, had been concentrating power in the executive branch, to the point that even staid auditors like the Economist Intelligence Unit have downgraded their estimation of its institutional health. And that was before Trump. Especially now, the perilous state of civil liberties and Philippine institutions serve as a stark warning: Popular, elected leaders can undo democracy, with the full blessing of their constituents.

Thanassis Cambanis, a fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author of “Once Upon a Revolution: An Egyptian Story.” He is a columnist for the Globe Ideas section and blogs at thanassiscambanis.com.