Young people and youthful energy propelled the Arab uprisings that began in 2010. And while the cohesion and impact of vaguely defined “youth” movements have been overstated, they remain the most important potential source of change—the Arab world’s best hope. The small vanguard that drove the original uprisings is growing more organized and more ideologically sophisticated even as, for the time being, it has lost political ground.

Egypt has always set regional trends in political thought. Its Tahrir Square uprising raised expectations for democratic transitions throughout the region, although the other Arab revolts brought wildly divergent results, especially for youth. Today the military appears to have won in Egypt, but the long-term outcome of the struggle there between revolutionary and reactionary forces is still in question; how it unfolds will be a bellwether for the Arab world.

Youth Is a State of Mind

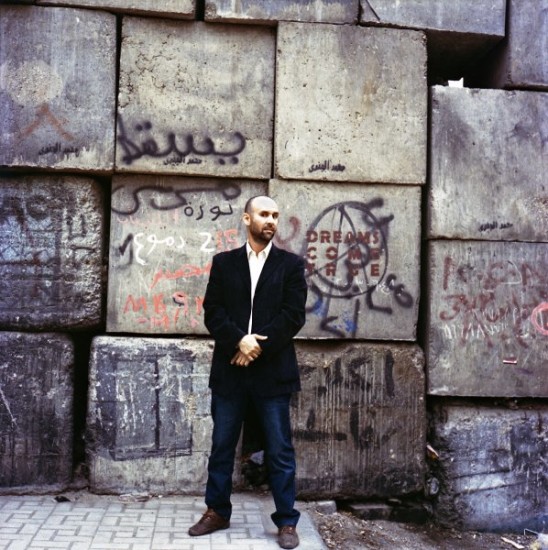

Basem Kamel makes an unlikely revolutionary youth activist. I first met him four years ago, inside the small tent erected by the Revolutionary Youth Coalition to house its big-tent deliberations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. He seemed decidedly middle-aged and established: balding, evenly shaved despite his sleep-deprived gaze, slightly stooped, his scruffy protest clothes accented with a knotted orange scarf. He was 41, father to three children, proprietor of an architecture firm. “Youth is a state of mind,” he laughed when I arched my eyebrows at his age.

But like the Revolutionary Youth Coalition and the fractious panoply of movements for which it briefly served as the umbrella, Kamel represented a radical challenge to the status quo. Against the mores of the ruling party, Kamel appeared young, pluralistic, open-minded, radically experimental and egalitarian. So were the other “revolutionary youth” I encountered in Tahrir Square, ranging in age from children to grandparents.

Kamel had gone within a year from apolitical observer to revolutionary policy wonk. He wanted to throw out the entire regime’s way of doing business along with then-President Hosni Mubarak. He wanted a rules-based social welfare state that encouraged entrepreneurship and initiative while efficiently taking care of the poor and vulnerable. He wanted justice for Egyptian citizens who had been abused by police and military personnel, and he wanted to see his fellow citizens learn to take responsibility for everything from litter to voting. “If we succeed, everything will have to change,” he said then. “It will take a long time.”

The Revolutionary Youth Coalition is no more. It collapsed a year and a half after its founding, because its secular and Islamist members lost trust in each other. It was the sole institution in Egypt that tried systematically to bridge the gap between Islamist and secular political actors. Elsewhere in the Arab world, only Tunisia’s Parliament has attempted the same feat, with equivocal success.

Yet despite its noble aims, the coalition also embodied the region’s political identity crisis in its very name. “Youth” and “revolution” are virtually meaningless as explanatory categories for what is taking place in Egypt and elsewhere across the Middle East. The Arab world today is in the grip of a regional struggle for control—and in some cases a fundamental redesign of government—being waged among many contesting visions: hereditary monarchs, old-fashioned nationalist states, incremental Islamists, nihilist jihadists, socialist reformers, anarchists and others. The young can be found in almost every one of these locales and movements, including the most reactionary establishment political parties and statist institutions. Similarly, some of the most creative and constructive political forces feature middle-aged or even old activists in inspiring roles.

The particular problems facing youth as demographically defined—completing secondary or higher education, finding a first job or career and establishing a family—are economic and social. And while young people have a special kind of energy that dissipates with age, none of these factors predispose the young toward any particular political tendency. Throughout the Arab region, as throughout the rest of the world, they are just as likely to be apathetic as political, or reformist as conservative.

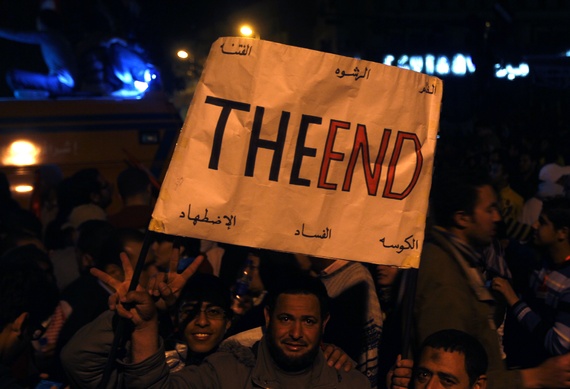

Nevertheless, a set of new political ideas and processes has been unleashed in the Arab revolts. The energy of young street protesters catalyzed a moment of revolutionary potential, a moment that shattered the assumption of regime staying power and opened the way for competitive politics and new ideologies. That fundamental idea—that a peaceful popular movement can replace a repressive state with a responsive, democratic, just and egalitarian polity—has survived today in a battered condition.

In Egypt, the country with the greatest potential and the greatest political impact on other Arab countries, the idea of change survives mainly in the beleaguered family of “revolutionary youth” movements, for which the country’s broken political system has made no room. The story is different elsewhere. Tunisia, for instance, has a plethora of young activists but no predominant set of youth movements, most likely because the existing political structure, with its parties and trade unions, engaged in meaningful negotiation that was able to harness the energy of young revolutionaries and channel it into a successful transition to democracy. Lebanon offers a third alternative—a paralyzed dysfunctional state where established sectarian parties have managed to absorb and dissipate youthful energy and momentum for reform, without making any improvements in governance or way of life.

A close and honest look at the condition of the Arab youth movements tells us a great deal about the prospect for systemic change in the region. At the core of the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia was a group of movements that espoused an agenda much more about revolution than about youth. Its supporters were concerned with political and economic injustice, and they touted democracy in a local vernacular, refusing the notion that it is a tainted or premature import from the west.

The revolutionary youth have been roundly defeated in Egypt. Tunisia’s more successful uprising has subsumed most of its youth activists into mainstream parties, perhaps a sign that political life is healthy or diverse enough not to require a binary external category such as youth to advocate for reform. Elsewhere, youth movements have remained marginal, as in Lebanon, or been sidelined by violence, as in Syria, Libya and Yemen.

But there is a clear and admirable agenda, one quite threatening to the region’s status quo regimes, articulated under the banner of revolutionary youth. Any Arab state that doesn’t grapple with its central claims and aspirations will remain fundamentally insecure, under threat any time circumstances conspire to make an opening for the latent uprising incubating in the warmth of their misrule.

The Bulge

The Arab world is disproportionately young; more than half of the population is under 25. Education systems are failing. Young people make up almost all the new entrants to the labor market, and the Arab region leads the world in youth unemploymentaccording to the United Nations. Demographers and economists who look at the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have rightly called attention to the youth bulge, including a looming one in Egypt, coupled with the region-wide systemic failures to educate citizens and provide them jobs.

The considerable scholarship about the demographic and economic implications of the youth bulge explains one of the many dispiriting constraints on growth and quality of life in the MENA region. A recent United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) paper summarizes the reams of demographic and economic analysis of the Arab youth imbroglio: “Without noticeable improvements in their economies or employment prospects, especially for much of the frustrated youth, rising demonstrations, unrest and violence appear unavoidable for the nearly half a billion people in the Arab world by 2025.”

But “demographic destiny” and the depressing economic conundrums of the Arab economies tell us nothing about the likelihood of political explosions, transitions or repression. Poor states that have little concern with the rights and welfare of their citizens can still perform at dramatically different points along a spectrum from murderous and self-destructive, like Syria; to aggressively indifferent, like Egypt; to muddling but occasionally passable, like Jordan. Regimes with massive youth bulges can successfully crush dissent, as Iran did to the uprising known as the “Green Revolution” in 2009, or escape it altogether with minor adjustments, as Saudi Arabia has done since the Arab uprisings. Demographics are not destiny, politically speaking.

Egypt’s Movement Youth

The past two years have brought a crescendo of terrible news for supporters of pluralism, rights and democracy in Egypt. The country’s first and only elected civilian president, Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, ruled erratically and eroded civil freedoms. He was deposed in a popularly acclaimed coup in July 2013.

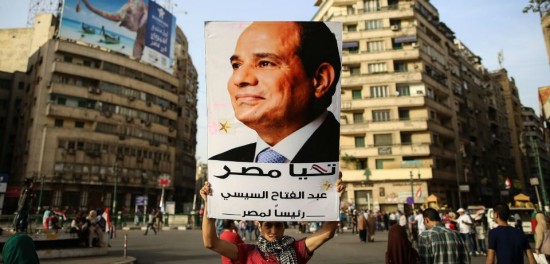

Reflecting the general patterns of society, an apparent majority of young people, including many activists, supported the anti-Morsi Tammarod protests. Only a tiny number of them immediately criticized the military’s direct takeover of power, although dissent quickened after the military regime massacred at least 1,150 Morsi supporters in Cairo’s Rabaa Square on Aug. 14. Egypt’s new leader, Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, swiftly moved to outlaw protest and ban the Muslim Brotherhood, and over time has arrested almost all the leading dissidents across the political spectrum. He has restored and intensified the repressive methods of the old regime and has banned critical figures from appearing in the media.

In one sense, the playing field looks like it did under Mubarak: A state behemoth that is terrible at governance uses a heavy hand to crush opposition, and faces a very small but committed activist community that includes old veterans and youthful newcomers.

But Sissi, a general who resigned from the military when he decided to seek the presidency almost a year after his coup, may face open revolt much earlier in his tenure than Mubarak, unless he indefinitely maintains his unprecedented levels of violent suppression. The generation of activists that propelled Tahrir has gone on to establish political parties, youth movements and other institutions. Its ranks have gained invaluable organizational experience. They have built vast interpersonal networks, bound by the shared experience of torture, detention, long prison sentences, exile and mourning. The brightest of the revolutionary leaders and movements have slowly begun to address their biggest failings; they are creating clearer, more compelling alternative ideas of governance, and they are developing strategies that take into account the volatility of mass public opinion.

Moreover, a significant portion of the socially conservative elite—the centrists who leaned slightly toward the revolution in 2011 and toward Sissi in 2013—has experienced political mobilization and the sense of power that comes with overthrowing a regime. Egyptians have acquired a taste for political empowerment and accountability.

A survey of the current state of the activist youth movements, as well as the widespread apathy among the youth demographic, can invite depression. Yet it is remarkable, especially when compared with the period before 2011, that in the face of historically unprecedented violent repression of all dissenters, from human rights lawyers to Muslim Brothers to bourgeois middle-aged civil society activists, a wide array of movements has persisted in opposition to the state.

Public opinion has gone into a version of political hibernation. Protests against Sissi’s government are small, and polls suggest transition fatigue. Some individuals who casually participated in protests or politics from 2011-2013 told me they had “lost faith in politicians,” “no longer trusted activists,” or were “ready for stability so I can get a job and have my life back.”

However, among the most dedicated activists, only a few have defected from politics entirely, while many have made notable shifts. Top among them are the organized revolutionary youth who have shifted allegiance entirely, best represented by the anti-Morsi Tammarod movement. Its original founders were five youth activists, including veterans from the April 6 Youth Movement and from former presidential candidate Ayman Nour’s Ghad (Tomorrow) Party. They mobilized a signature campaign against Morsi, and after the coup they became stalwart cheerleaders for Sissi’s elevation from junta leader to elected president. Tammarod is undeniably a reactionary force that has benefited at times from state support, but it is also undeniably a youth movement toward which Sissi’s government has turned a jaded eye.

Basem Kamel, the 41-year-old revolutionary “youth” I met in Tahrir four years ago, went on to co-found the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, which has now positioned itself to the right of its revolutionary roots as a traditional liberal party. He became one of just a handful of revolutionaries elected to the short-lived parliament of 2012. After the Sissi coup, Kamel and his party supported Sissi’s transitional government, prioritizing secularism and a fight against the Muslim Brotherhood over opposition to military rule. “I didn’t support Sissi, I opposed Morsi,” he told me this winter. “Whatever we are now, it is better than the Muslim Brotherhood.” He now sounds like a cautious reformer rather than a principled revolutionary.

Kamel opposes Sissi’s crackdown on protest and free speech, but he believes it will take years or decades for vanguard activists to convince the Egyptian public to support a genuine move away from military rule. He has chosen to work within a political party that has been allowed to continue operating by the regime as part of a trusted or permitted opposition.

Youth and revolutionary politics continue to exist, despite the crackdown under Sissi, because of systemic state failures. Police still torture with impunity; runaway judges make a mockery of the rule of law; army officers control political life; and the economy continues to fail the vast majority of its citizens, while a corrupt elite connected to the army and a ruling clique rakes in rentier profits.

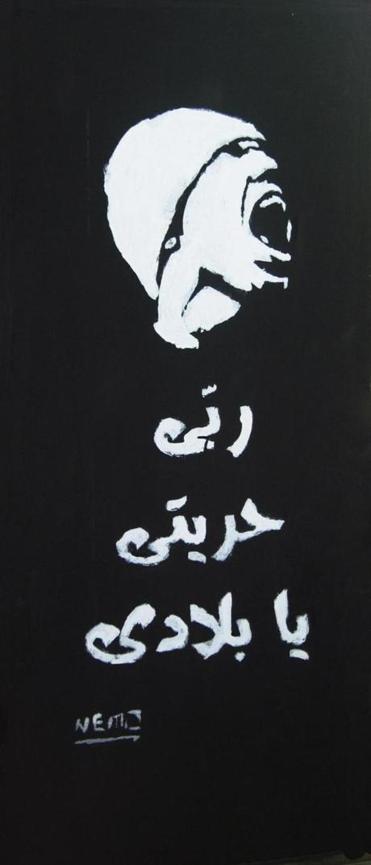

And the most visible independent activists have continued to agitate, demonstrate or write treatises even from prison. Alaa Abdel Fattah, an independent leftist who helped form a revolutionary coalition after the Rabaa massacre, has produced a powerful oeuvre from his jail cell. Most recently, this fall he spurred a wave of partial hunger strikes under the slogan “We’re fed up.”

Meanwhile, the April 6 Youth Movement, a grassroots movement that has made deep inroads among working-class Egyptians, has survived a concerted effort by the state to dismantle it, in part because the movement’s leaders and members have in fact collaborated with right-leaning nationalists. These positions drew enmity to the movement, but they also put it more closely in step with the Egyptian mainstream. Perhaps for this reason, April 6’s grassroots network has survived the imprisonment of its leadership. As recently as November, it was able to muster a sizable protest in Tahrir Square, along with other secular, non-Islamist revolutionary groups angered by a judicial verdict clearing Mubarak of further charges.

Egypt’s Islamist Revolutionaries

The final locus of continuing resistance activity in Egypt comes from the Islamist space. Always the largest, most organized and best-funded opposition to the state, Islamist groups have always had formidable youth wings. During the revolutionary period, the Islamist political space fragmented. Today it still includes the largest number of active opponents to the Egyptian regime, although many of those activists are young Muslim Brotherhood members calling for Morsi’s reinstatement. They are increasingly isolated not only by the state, but from revolutionary movements who view Morsi’s autocratic tenure as a betrayal.

Yet a principled group of former Muslim Brotherhood members forms one of the most interesting revolutionary cohorts. Hundreds of young men and women who were among the elite of the Brotherhood’s official youth movement defied their hierarchical organization bosses and took part in the original Jan. 25 uprising in 2011. Most of them believed the Brotherhood should stay out of politics and remain a social and religious organization. These were pious and committed Islamic youth who believed in a secular, pluralistic state. Three of them were founding members of the Revolutionary Youth Coalition; they were among the first Brotherhood youth officially expelled by the hierarchical Islamist group.

They founded a political party, the Egyptian Current, which failed to attract wide membership. Some of its members work as independent activists or have joined secular political parties. Many of its best-known leaders now work with Strong Egypt, the political party of an ex-Muslim Brotherhood leader and presidential candidate, Abdel Monem Aboul Fotouh. Strong Egypt has been one of the only political organizations to condemn authoritarianism quickly and consistently, whether practiced by liberal civilian politicians, Morsi or Sissi. It forms the only existing bridge between secular revolutionaries and the powerful Islamist bloc, which for now has distanced itself from a project of pluralism, reform or revolt.

But the distrust between the two camps runs too deep for the kind of cooperation it would take to effect meaningful change in Egypt, and continuing efforts to mediate between anti-regime revolutionaries and Islamists have failed so far. Moaz Abdel Kareem, a former Brother and Revolutionary Youth Coalition member, has been one of the most persistent advocates of secular-Islamist collaboration. “It is crazy to think we can have a revolution without the Islamists,” he told me recently over a water pipe in a cafe in Istanbul. “We need to start a dialogue and agree on things we can fight for.” His own predicament suggests the impossibility of unity now; his old Islamist colleagues reject him as far too secular, while his revolutionary colleagues suspect he’s still secretly a Muslim Brother.

Illustrating the divide, in late November, secular revolutionaries rebuffed a public call from the Brotherhood for “revolutionary unity.” An April 6 spokesperson told Mada Masr, an independent Egyptian publication, that his organization would never again trust the Islamists, while a member of Strong Egypt said it was waiting for the Brotherhood to revise it positions and prove it could “keep its word.” In a further illustration of the exclusion of political “youth” dynamism by established political players, the Muslim Brotherhood itself criticized its own young members for going too far in their efforts to forge a united front with secular activists. The Brotherhood’s paternalistic tone echoes that of first Mubarak and now Sissi, with its patronizing dismissal of youth politics as naive, subversive or outright traitorous.

Sissi is unlikely to address Egypt’s core failures: the collapsing economy, the utter lack of justice or rule of law and the smothering of political life. In Tahrir Square in 2011, many people told me they had finally been motivated to protest because the state “humiliated” them: It prevented them from supporting their families, and it didn’t allow them the slightest political voice. The implication is clear. A regime might be able to get away with corruption and misrule if it allows some democratic expression, or it might get away with oppression as long as it delivers basic quality of life. But it will have trouble keeping its population quiescent if it fails on both counts.

The Role of Youth Beyond Egypt

Beyond Egypt, the entire Arab state system has been called into question, which is why powerful vested interests from the Gulf monarchies to the region’s nationalist militaries have engaged so fully in what they rightly view as an existential struggle. Nearly every country in the region has responded to these profound forces, although it is still early in their historical lifespan. Each Arab state offers a model of how to crush, harness or coopt revolutionary energy.

Short of war, there are three general approaches. The first is to deploy a police state to marginalize revolutionary ideas; Egypt is the leading example, but Bahrain and to some extent Jordan have followed a similar approach. The second is to embrace revolutionary energy within the system and attempt a transition: Tunisia has done this most successfully, although at periods Yemen and Libya seemed to have managed some degree of systemic change. The third is to redirect or absorb the revolutionary energy with neither a frontal clash nor a sincere effort to respond to its demands: Lebanon is the quintessential master of this sort of twisted jujitsu approach, although its principles can be seen at work in the maneuvers of regimes in Morocco, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. A closer look at Tunisia and Lebanon, as alternatives to Egypt’s course, also highlights the problem with relying on youth as an organizing principle to explain Arab politics.

Tunisia, Model or Exception?

Increasingly, Tunisia seems like an outlier in the Arab world. Its peaceful uprising was disproportionately younger than Egypt’s, and it was quickly supported by key institutional players, including the military. The biggest political blocs, the Muslim Brothers and the secular trade unionists, managed to negotiate a consensual constitution and a balanced transitional government despite their divergent visions. Islamists voluntarily ceded power after losing in Tunisia’s second elections. Not everyone is satisfied, but none of the key constituencies profess to have been locked out of the political transition, in contrast to Egypt. Perhaps most important in the context of the current discussion is the fact that “youth” were not ghettoized, but rather dispersed across the spectrum of politics and civil society.

Tunisia is a small nation whose relative wealth and education levels make it hard to compare to other Arab countries. Yet activists elsewhere in the region have drawn some key lessons. Tunisia benefited from a balance of power that included trade unions with a sizable, organized following, and also from a wise provision in the transitional electoral system preventing the winning party from amassing an absolute parliamentary majority. The main parties engaged in sincere, if occasionally acrimonious, negotiations. Islamists repudiated violence committed by their supporters, while secularists have avoided the taint of military authoritarianism that has come to characterize so many of their Egyptian counterparts.

This is perhaps a result of the fact that, while in exile years before Tunisia’s uprising, Muslim Brotherhood leader Rachid Ghannouchi and liberal dissident Moncef Marzouki met regularly, despite their profound ideological differences. Their relationship produced a level of institutional trust during Tunisia’s initial transition period, when Marzouki was president and Ghannouchi’s party controlled the government.

The Lebanese Alternative

For better and often for worse, Lebanon’s muddle-through system of compromise and patronage has become a regional model. Once dismissed as dysfunctional and corrupt, Lebanon’s solution to its 1975-1991 civil war has come to be seen by many other regional actors as a lesser evil, often worth emulating. Iraq might have accelerated the path to sectarian civil war by adopting a Lebanon-style sectarian ethnic quota system, but many there still see “Lebanonization” as a palliative and a preferable alternative to a bloodbath. Syrian activists who in 2011 swore they would never be “another Lebanon” now tell me that ending up like Lebanon after a decade of fighting might be the best hope they’ve got.

Lebanon’s volatile stalemate has staved off civil war and internal political revolt despite myriad systemic failures to address the concerns of ordinary citizens, especially unemployed or underemployed youth. In this, Lebanon might once again suggest a somewhat distasteful workaround.

Interestingly, no substantive youth or revolutionary or reform movement has emerged in Lebanon since the Arab Spring uprisings. Polling and anecdotal evidence suggest that the majority of Lebanese resent the spoils system of governance, controlled by the same major warlords who have dominated politics since the civil war. Yet their economic energy has been dissipated, either absorbed into the corrupt spoils system at home or dispersed into Lebanon’s vast diaspora, the proceeds from which prop up the country’s crippled economy.

Youth are freer in Lebanon than anywhere else in the Arab world to engage in cultural activity, although state security censors still carefully police the boundaries of free expression to silence radical critiques of the power structure. But that freedom doesn’t extend to politics. Young Lebanese are free to harness their political energy into the vibrant youth wings of the existing political parties, but not to challenge the status quo. All the major factions have intricate institutions to tap into youthful energy, including scouts, paramilitaries, social clubs, student council elections, fundraising work and ultimately party membership. Opportunities for political participation are limited to the existing sectarian parties.

One exception is the on-again, off-again movement in support of civil marriage, which remains elite, small and, while threatening to the sectarian spoils system, neither radically revolutionary nor inherently political. Presently, the civil marriage cause appears dormant. In times of heightened security fears, the demands of civil society in Lebanon tend to be drowned out, although a dedicated core group of civil society activists has persisted in the face of decades of pressure and ups and downs.

Conclusion

The political movements that challenged the Arab world’s established order in 2010 and 2011 are still in the process of developing. Their ideas and platforms are inchoate, and their leaders and core members are often under attack. In multiple countries, including Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Bahrain, proponents of even nonviolent incremental reform have been subject to terrifying levels of state violence. Elsewhere they have been systematically but less bloodily silenced or co-opted, including in Jordan, Qatar, the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

But it seems obvious that these movements are not going away, just as the Muslim Brotherhood, with its compelling ideology and disciplined organization, has never disappeared—despite repeated attempts at state-sponsored eradication—since its founding in 1928.

The great energy and aspirations that drove the revolts haven’t disappeared, even if the revolutionary leaders in Egypt have been marginalized for now. There on the margins, they are still working.

Kamel has concluded that the fault lies not with Egypt’s stars, but its citizens. “We have fought four regimes in a row, but most of the people of Egypt are not with us,” he told me this fall. “The problem in Egypt now is not the regimes. It is the people. We have to convince them.”

Some still believe that Sissi’s overreach will drive people together again, just like Mubarak’s abuse of power did in January 2011. “The Mubarak verdict shocked people,” Abdelkareem, the ex-Muslim Brother and Egyptian Current founder currently in exile, told me. “Now the youth are starting to cooperate again.”

Throughout the region, the same force that drove the uprisings has been redirected. Some of it simmers out of sight. Some of it has poured into the call for violent takfiri jihad in Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Egypt and perhaps elsewhere. Some of it has flowed into the quiet, continuing organizing of the political parties, youth movements and civil society groups that challenged status quo power. In Egypt, Sissi’s regime will either have to address these aspirations or fight a constant rear-guard war against dissent. The harder it fights, the more dissenters it will find.