From Tahrir to Wall Street

It was supposed to be a master class in revolutionary activism: two stars of the Tahrir Square uprising visiting Occupy Wall Street to swap tactics and sass. It ended up more like an undergraduate teach-in.

For Asmaa Mahfouz and Ahmed Maher, the visit to Zuccotti Park was an exhilarating – if surreal – break from the punishing workload of fighting the military dictatorship back home in Egypt.

“Where is the tear gas?” Maher asked with a smile, but he seemed genuinely puzzled by the cordial relations between the Wall Streeters and the cops.

Maher and Mahfouz both have been arrested before by Egypt’s notoriously abusive police, and Mahfouz recently was hauled before a military court martial for allegedly insulting her country’s military rulers.

Mahfouz had a question of her own. “Where are the organizers?” she asked. “There must be organizers.” No one knew. She ended up chatting at the welcome table with a young man wearing a straw hat.

“How do you sustain yourselves? How do you keep yourself energized?” he asked. “That’s our main problem.”

“You need a message,” she told him.

She inscribed an Egyptian flag (“From Tahrir Square to Wall Street”) with black marker and presented it to the hundreds who gathered to hear her and Maher.

Mahfouz, 26, spent years protesting when most Egyptians stayed home, and became a phenomenon with her self-produced YouTube editorials. She lambasted rulers with homespun humor, and exhorted people to join her at protests. Eventually they did, in the millions.

Maher, 31, worked with virtually every activist group in Egypt, and founded the April 6 movement, which was instrumental in organizing textile worker strikes in 2008. His grassroots political organization boasts the kind of street muscle and labor ties that Occupy Wall Street still only hopes to build.

People asked about the role of women in the Egyptian uprising, the connections between youth and labor movements, and the importance of social media. Some of the questions were well intended but astonishingly vague: “How do you overthrow a system?” one man asked. Maher politely replied, “It’s easier to overthrow a dictator than an entire system.” He didn’t belabor the point that the Egyptian revolutionaries, so far as they are concerned, have not yet won; they still are fighting their system. Egypt’s military rulers have staged a vicious campaign against Maher’s April 6 movement, accusing them with no evidence of working as American spies and subjecting them to a public inquiry.

The Americans wanted to know how they could help Egypt.

“Get your revolution done. That’s the biggest help you can give us,” Mahfouz said, expressing the hope that America would one day cut off the $1.3 billion yearly payments that sustain Egypt’s military.

She also advised Occupy Wall Street to select its own leaders and craft a simple message “that no one can change.”

On Monday evening at Zuccotti Park, Mahfouz was eager to model the fiery disobedience with which she’s inspired countless Egyptians. “Let’s march!” she said after an hour-long question-and-answer session, grabbing an Egyptian flag and flashing the victory sign with both hands.

A few hundred demonstrators fell in line behind her and Maher, who gamely joined the English chants. The police allowed the march onto Wall Street itself, and at each corner the American leaders consulted an officer about the preferred route. Weary of the somewhat stilted slogans, which lacked the umph and rhythm of Egyptian chants, Mahfouz and Maher taught the crowd the iconic cry of the Arab uprisings: “Al shaab yurid isqat al nizam,” or “The people demand the fall of the regime.” The crowd adopted its own hybrid: “Al shaab yurid isqat Wall Street.”

As they wound back to Zuccotti Park, demonstrators awaited a cue from the police before crossing Broadway. It was too much for Mahfouz. She stopped in the middle of the intersection, stopped traffic, pumped a fist in the air, and demanded the fall of Wall Street. Nervous demonstrators skittered to the sidewalk, leaving Mahfouz with just the cameras and a few dozen stalwarts who seemed willing to accept her invitation to be arrested.

For a few seconds, there was a palpable crackle of tension. But the police, it seemed, didn’t want the hassle. They stepped back, and without a confrontation, the moment subsided. Mahfouz joined her comrades back on the sidewalk.

“I wanted to show them that they need to be tough, even if they get arrested,” she said with her trademark toothy smile. With that she repaired for a private session with Occupy organizers – she finally had found them – and the long trip back to Cairo the following day.

What the Generals Did to Egypt

[Originally published in The New York Times Sunday Book Review, subscription required.]

[Originally published in The New York Times Sunday Book Review, subscription required.]

Review of The Struggle for Egypt: From Nasser to Tahrir Square, By Steven A. Cook. Illustrated. 408 pp. Oxford University Press. $27.95.

On the morning of Feb. 11, 2011, hours before Hosni Mubarak submitted to the millions of his subjects clamoring for his resignation, a half-dozen retired generals sipped coffee poolside at the Gezira Club, kitted up for tennis and contemptuously dismissed the demonstrators in Tahrir Square. “Who do they represent?” scoffed a man who until recently had worked in state security. “They are loud, but don’t forget there are 79 million Egyptians who are not in Tahrir Square. They are the majority.”

It never crossed their minds that Mubarak might capitulate, as he would do later that day, or that the passivity of most Egyptians did not equal support for a regime that had squandered Egypt’s position at the head of the Arab world while excelling only at abuse and corruption. That rank incomprehension — one might less charitably call it arrogant cluelessness — stretched from the coffee klatch at the Gezira Club through the entire government. Yet Egypt had managed to remain a stable linchpin of American policy in the Middle East for decades, until suddenly it wasn’t.

This transformation, along with the internal decline from pride of the Arab world to shameful decaying autocracy, is the subject of Steven A. Cook’s “Struggle for Egypt: From Nasser to Tahrir Square.” The book clearly was in the making long before the uprising.

Cook’s central contention is that since the military coup of 1952, Egypt’s leaders have never had an ideology. Instead, they have resorted to an increasingly complicated and cruel apparatus of coercion, bullying the citizenry into consent but failing to create any positive reason to support the state.

Cook isn’t trying to tell us why Egyptians revolted in 2011, or what might come next, although his perceptive analysis helps answer both questions. His real aim is to diagnose Egypt’s decline and directionlessness in the modern era, from Nasser’s charisma to Mubarak’s dead-man governing act, and to shed light on America’s role. With meticulous historical context and the acumen of a political scientist, Cook, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, weaves together a narrative drawn from archives, interviews and his own firsthand reporting during a decade of visits to Egypt.

His story begins with a quick survey of Egypt’s modern political awakening, an excellent primer for the uninitiated. Egypt first revolted against its colonizers in 1882, ushering in an age of ferment that included a British-dominated monarchy and a religious awakening inspired by the pioneers of the Islamist revival. Corruption flourished, as did ego-driven power struggles within the elite. Disgust began to reach a boiling point in 1948, when Gamal Abdel Nasser and his Free Officer compatriots fought in Palestine against the newly declared state of Israel. Between the king’s incompetence, the greed of the governing liberals and the Machiavellian scheming of the British, who humiliatingly still occupied the Suez Canal, Egypt’s leaders were doomed.

Nasser’s coup in 1952 threw all the bums out and placed power in the hands of a small group of young, unknown officers, who promised to advance the national interest as impartial technocrats. A charismatic orator, Nasser became the voice and conscience of Arab nationalism, and experimented with reforms that gave land, education and jobs to the peasantry.

Egypt’s people invested great hope in the idea of an apolitical, incorruptible military leadership — a comprehensible but unfounded reflex that prevails again today. The Free Officers tapped a deep and historically grounded wave of rage against foreign interference, a backlash that has never subsided.

Nasser flirted with the Soviets but never embraced Communism. He used the Muslim Brotherhood to achieve power, then ruthlessly crushed the organization when he realized it was becoming too popular to control.

By the time his mismanaged army collapsed in the 1967 war with Israel, Nasser’s reforms had stalled. Anwar Sadat, the weak officer who inherited the presidency in 1970, carved out a power base by gutting what remained of civil society. Sadat relaxed the restrictions on the Muslim Brotherhood and encouraged free enterprise, spawning a wealthy new elite that matured into Mubarak’s crony capitalist circle.

Cook does an excellent job telling the story of Sadat’s daring trip to Jerusalem, which quickly and unexpectedly led to the Camp David accords — a peace treaty almost universally reviled in the Arab world, including Egypt. With that one move, Sadat managed to become the darling of the West, while sacrificing almost all his domestic support. Few of his countrymen mourned when he lost his life to an assassin’s bullet in 1981, and his vice president, Hosni Mubarak, assumed power.

The lesson for Mubarak and Egypt’s ruling class was to risk nothing. Gone was Egypt’s sense of destiny as helmsman of the Arab world. Abandoned, too, was the confidence to imagine developmental leaps forward like the Aswan dam.

The joke goes that upon being sworn in, Mubarak took his first ride in the presidential limo. The veteran driver reached a fork in the road. “Nasser always turned left here,” the chauffeur said. “Sadat always turned right. What would you like to do?” After long thought, Mubarak decided: “Just stay where we are.”

Under Mubarak, poverty and inequality leveled off for a time but then began to increase again. The sacrifice of liberties ceased to be a Faustian trade-off for security and economic progress once the government could no longer deliver on bread-and-butter issues. Egypt became little more than a byword for a brutal security state — though one that was a stalwart ally to Washington and Jerusalem.

By the 1990s most of Mubarak’s energy was going into suppressing political dissent and fighting to preserve his special relationship with Washington. He deployed an army of secret police officers and informants that rivaled East Germany’s, infiltrating everything from the doormen’s union to student theater groups. But by 2011, spies, tear gas and heavy-handed repression were not enough to keep him in power.

Readers looking for a full account of this year’s uprising will have to wait for the spate of coming books by journalists, insiders and political analysts. What Cook has given us is a scholar’s well-informed, analytical history, which offers invaluable insights to anyone interested in how Egypt came to its present impasse. “The Struggle for Egypt” is at its best when delivering finely honed details, as when Cook explains the relationship among Egypt, America and Israel. He offers a surprisingly engaging disquisition on Public Law 480, the American “Food for Peace” program that was the progenitor of an unhealthy aid-driven relationship between Washington and Cairo.

But Cook’s storytelling is laced with clichés and hackneyed images (“jaw-dropping,” “live wire”). This is the kind of book where “the mist off the Nile . . . creates an odd sense of foreboding and anticipation” on the morning of the 1952 coup. (Was it really the mist, or was it the tanks surrounding all the government buildings?) He awkwardly drops characters he has met into his account without any apparent connection to the narrative, only to allow them to disappear a few pages later.

These stylistic hiccups, however, are merely occasional irritants in a substantial and engaging book. Cook knows his material and gets the important points right. His account should be particularly sobering for American readers, who will find in these pages a damning exposition of why United States aid and political influence are currently viewed with such profound suspicion in Egypt.

History offers today’s Egyptian reformers many warnings, most importantly about the danger of an unaccountable, all-powerful military. Egyptians have long suffered from the gap between their leaders’ rhetoric and practice. Nasser, Sadat and Mubarak spoke the language of revolution, Arab pride and economic prosperity, but presided over a military welfare state that impoverished its people and ruled through systemic torture. This disconnect will plague anyone who tries to resuscitate Egypt after Mubarak. For if the man who ruled for 29 years, 3 months and 28 days is gone, the dysfunctional, Orwellian system he did so much to create and sustain lives on.

Some pre-Maspero Thoughts

Which way is Egypt’s revolution heading, and what is the ongoing military dictatorship doing? I wrote the following at the end of last week, before Sunday night’s killings at Maspero. Read with that in mind. The moment is a glum one, with the increasing evidence that the ruling junta won’t hesitate to use the most crude and violent methods of Mubarak and his predecessors. The military council has kept its goals opaque. None of this assessment is intended to be predictive. Egypt’s uprising already has defied unbelievable odds, and there’s no reason to think it will fail to change the system at this point, after only eight months. But there’s also no reason to think the old regime won’t fight for its own survival.

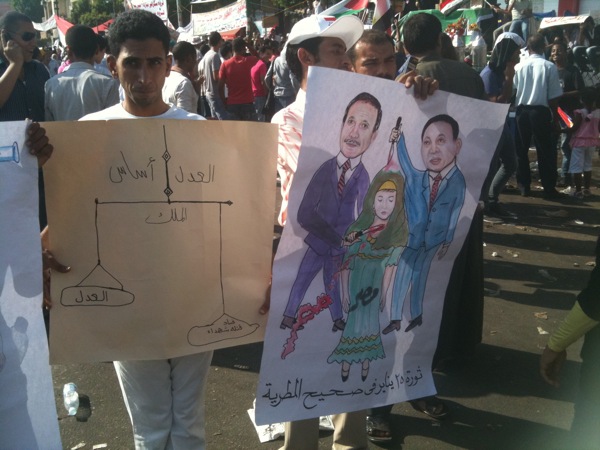

CAIRO, Egypt — The enraged crowd had a target: the satellite television transmission truck parked at the edge of Tahrir Square, by the Hardees. “Get out, get out!” screamed a hundred men, while the most agitated swarmed the truck, pounding it with their open palms. A half-dozen toughs fended them off. One brandished a pocket taser. Why, I asked a bystander, did this mob want the television signal silenced?

“Some channel broadcast there were only a few hundred people in Tahrir,” he explained. “We can’t have that.”

Except, of course, that it was true. This past Friday, October 7, was “The Friday of ‘Thank you, now please return to your barracks.'” It was intended as riposte to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which of late has reinstated many of the most decried and oppressive practices of the late Mubarak regime, and capped off its assertion of junta power with a grand martial celebration on Egypt’s national holiday to observe the victory against Israel on October 6, 1973.

The activists are terrified and energized, but the wider public does not seem to share their fears. So Tahrir, from Friday to Friday, seems emptier and emptier. What that proves is an entirely different question, but it is an observable fact that elicits anxiety to the Tahrir revolutionaries and satisfaction among supporters of the military council.

Revolutionary demonstrators are angry, and afraid their gains are slipping away. And like many Egyptian political players, they are not all instinctively liberal, as evidenced by the flashmob that would rather tear up a TV truck than admit that, this one time, state television was telling the truth about the paltry protest turnout.

I saw similar explosions of anger from skeptics of the revolution (or maybe just average, apolitical citizens) irritated by the disruptions caused by labor strikes. Workers are demanding living wages, and some of them are overtly trying to keep the revolutionary spirit alive while pressuring the regime, which at most levels has preserved the exact same stifling policies and personnel that Mubarak put in place.

In downtown Cairo, stranded commuters cursed the bus drivers, who are on strike because they want to earn a base salary higher than $100 a month. I was stranded overnight at the Luxor Airport after air traffic controller shut down Egypt’s airspace, and I heard travelers rail against the pampered workers who, emboldened by the revolution, were now heedlessly and selfishly inconveniencing their fellow Egyptians.

It’s hard to escape the feeling that Egypt’s January 25 Revolution is being eaten alive. It’s too soon to write it off, and too soon to predict that a full-fledged military dictatorship will rule the country for the foreseeable future; but that grisly outcome now is a solid possibility, perhaps as likely an outcome as a liberal, civilian Egypt or an authoritarian republic.

Eight months after a euphoric wave of people power stunned Egypt’s complacent and abusive elite, it’s possible to see the clear outlines of the players competing to take over from Mubarak and his circle, and to assess the likely outcomes. The scorecard is distasteful. The uprising — it can’t yet be fairly termed a revolution — forced the regime to jettison its CEO, Hosni Mubarak, in order to preserve its own prerogatives.

In the last two months, that regime has made clear how strong it feels. In September, in quick succession the military extended the hated state of emergency for another year, effectively rendering any notion of rule of law in Egypt meaningless; unilaterally published election rules that favor wealthy incumbents and remnants of the old regime, and that disadvantage new, post-Mubarak competitors; indefinitely postponed presidential elections, and refused any timetable for handing over authority to a civilian; reinstated full media censorship, threatening television stations and imposing a gag order on all reporting about the military; and the country’s authoritarian ruler, Field Marshal Mohammed Hussein Tantawi, unleashed a personal public relations campaign on state television odiously reminiscent of Mubarak’s image-making. Furthermore, the government advanced its investigation of “illegal NGOs” that allegedly took foreign money, including virtually every important and independent dissident organization.

Taken together, these moves show a military junta fully confident that it can impose measures of control as harsh — or, in the case of widespread military trials for civilians, harsher — than those employed by Mubarak.

Politically, the military council might seem incoherent, habitually announcing extreme positions and then undoing them after the next street protest, but the overall arc is unmistakable, if hopefully not inexorable.

The soundtrack for the SCAF and its millions of supporters in Egypt (because let’s not forget, the old regime had its loyalists and there are many more who remain convinced by state propaganda that the January 25 uprising was a plot against Egypt) could be the song from the satirical film Bob Roberts: “The Times they are a-changing back.”

Former ruling party members have regrouped. They have lots of cash and experience, and plan to run aggressively in the parliamentary elections that begin in just seven weeks, on November 28.

Meanwhile, the opposition to Mubarak is as fragmented as ever. The revolutionary zeal of Tahrir Square has flagged. Many of the most determined activists from January 25 have invested themselves in electoral politics, which they know is a long game. They’ve committed to build real political organizations, but it’s not clear how good they’ll be at doing so, or how quickly they can accomplish it.

The Muslim Brotherhood and a few tarnished, coopted official opposition parties like the Wafd already had nationwide organizations when Mubarak fell. The rest — the people who actually took to the streets in January — are struggling to make meaningful inroads and to learn the business of politics.

The Revolutionary Youth Coalition, which includes all the most credible groups from January 25, is trying this week to forge a unified slate of parliamentary candidates. But even if they’re wildly successful they won’t convince the crucial Islamists to join them.

With no experience of participatory politics, the parties are having to learn much too quickly, in a burning crucible. In September, leaders of the Revolutionary Youth Coalition accepted an invitation to meet with the head of state intelligence. The official, they said, tried to explain the government’s efforts to both secure the nation and to improve basic rights, and that the activists responded with their own demands for more reform. They deliberately publicized the meeting — and were then roundly rebuked by many of their own followers as sellouts.

A more extreme exercise in political trial-by-fire occurred the last weekend of September. The leading political parties negotiated with the military council over the authoritarian and opaque election law. They wrested some key concessions from the junta, including limits on former ruling party members running for office and a rule change that will allow political parties to run candidates for “independent” seats. But the final communiqué signed by the party heads included nothing solid about ending the state of emergency, retrying the civilians convicted in military courts, or most importantly, transitioning to civilian rule. In fact, the agreement between the political parties and the military left open a scenario in which a new civilian president won’t take office until 2013, more than two years after the Tahrir Square protests began. More woundingly, it included a sycophantic blessing to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.

As soon as the document was published, there was an uproar. The leader of the liberal Adel Party rescinded his signature. The Egyptian Social Democrats, who had only tentatively endorsed it, eventually signed but only after several influential members resigned in protest. The agreement was widely viewed with disgust. Some pundits suggested that the activists were struggling to adjust to the messy give and take of politics. A more accurate analysis would say that the party leaders got snookered by the Supreme Council for the Armed Forces, signing a document when they could have trumpeted the concessions they won while pushing for more. Even more importantly, the parties got a lesson in accountability politics that will mark the more adaptive among them like a cattle brand. Even revolutionary politicians aren’t used to representing real constituents, who speak up, and speak up loud, when they don’t like their leaders’ decisions.

The September fiascos are a snap clinic in electoral politics, and are taking place in hothouse where rule of law and liberalism are at best tenuous aspirations. Revolutionary activists who profess to value liberalism and rule of law see no irony, and no danger, in calling for the application of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s 1950s Treason Law to block the return of the Mubarakistas. They forget, or ignore, that Nasser used that law to shut down political life entirely, and that criminalizing the “pollution of public life” endangers anyone who disagrees with the powers that be.

Time is short until elections, and recent events have established that the military controls the process, whatever it might be. That process changes from week to week; the uncertainty and backtracking and vagueness increasingly look like a strategy by the junta to keep everyone else off balance and maximize the divisions among any pretenders to authority.

It’s possible that the military doesn’t want a return of the old regime — perhaps because it has begin to enjoy the prospect of keeping for itself all the power that it accrued when Mubarak went away.

Outside the Coptic Hospital

This was the view from the 6 October overpass, looking down at Ramses Street just before midnight. Reporters saw 17 (or 16) bodies in the morgue in the Coptic Hospital there, some shot dead, others killed by being run over. Crowds surging toward the hospital from the direction of Tahrir Square chanted “Islamiya, Islamiya!” Many were carrying truncheons. They threw rocks. The people in front of the hospital threw rocks back. A bus burned, its engine parts and tires exploding every few moments while black smoke belched upward. Four cars were burning as well. Around midnight, the warring sides merged and began chanting “Muslims, Christians, one hand.” It was near impossible to approach the hospital itself. After I left, the military apparently deployed to the street, more than four hours after violence broke out.

This was the view from the 6 October overpass, looking down at Ramses Street just before midnight. Reporters saw 17 (or 16) bodies in the morgue in the Coptic Hospital there, some shot dead, others killed by being run over. Crowds surging toward the hospital from the direction of Tahrir Square chanted “Islamiya, Islamiya!” Many were carrying truncheons. They threw rocks. The people in front of the hospital threw rocks back. A bus burned, its engine parts and tires exploding every few moments while black smoke belched upward. Four cars were burning as well. Around midnight, the warring sides merged and began chanting “Muslims, Christians, one hand.” It was near impossible to approach the hospital itself. After I left, the military apparently deployed to the street, more than four hours after violence broke out.

Latest Egypt torture video

If you’re interested in how torture and police brutality works in Egypt, take a look at this video, which is making the rounds this week and provoking a lot of anger. Allegedly, this torture session took place at a police station in the El-Kurdi police station in the El-Daqahliya governorate, and involves police as well as soldiers. What’s most striking here is not the violence and brutality, but the casual good cheer with which it is dispensed. These men are in an office, they know they’re on camera, and they’re not self-conscious in the least. The man who repeatedly electrocutes the detainees chuckles after delivering a shock. This appears to be what institutionalized torture looks like. Reliable accounts and the hard work of human rights researchers and activists suggest it’s as endemic as ever in Egypt, even since the revolution.

Inside Egypt’s Military Mind

CAIRO, Egypt — Retired Egyptian Army General Hosam Sowilam knows how to control a conversation. With a jocular smile and a booming voice, he’ll hold and repeat a phrase — “Chaos! Chaos! Chaos!” — until he’s drowned out the question he doesn’t care to answer, dispelling even the shadow of doubt as he regains the floor.

“What happened on January 25?” Sowilam bellowed by way of introducing his history of the uprising in Tahrir Square. “Many of our youths went to Serbia and the United States of America, where they received training in how to overthrow the regime. They received training from Freedom House, and funding from the Jewish millionaire Soros.”

He goes on to weave a detailed story of a foreign plot against Egypt, in which unscrupulous agents from America, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, backed by a web of corporate interests, took advantage of Egyptians legitimately dissatisfied about Hosni Mubarak’s plan to transfer power to his son.

“Look!” he says, pointing in a bond dossier at a page of logos from companies like Edelman and CBS. “All these corporations were behind the Arab spring. This is very dangerous.” There are headlines about Soros from websites like truthistreason.net and AnarchitexT.org (“I don’t know any thing about them,” Sowilam says. “I found them on the internet.”) Other data comes from better-known sources like The Washington Post and Wikileaks. He has carefully translated key points into Arabic to share with Egyptian reporters.

Although Sowilam holds no official role in the army that governs Egypt today, he considers that army his life, and relishes any chance to speak for its values and mindset, if not its official policies. He remains close to senior officers, and had a second career after the military at a defense think tank and now as an unofficial spokesman for the military. (I first met him a year ago while reporting a story about the military’s view on then-President Mubarak’s succession plans; Sowilam adamantly criticized the notion of hereditary power, but also warned that the military never would permit Islamists to rule Egypt.)

Bald and squat, with a body shaped like a calzone, Sowilam has the typical build of an artilleryman. An early career surrounded by the thud of big guns marred his hearing, which is why he often shouts in casual conversation. Born in 1937, Sowilam came of age and attended the military academy in the 1950s, in the halcyon era of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Free Officers revolt. He took his commission when the army was at the zenith of its power, boldly refashioning Egypt’s political and economic order. He fought in the humiliating defeat of 1967, which he directly attributed to the Free Officers’ “disastrous experiment” with running the country. He later served abroad, including a stint as military attaché in India.

Egypt: Now What? (in The Guardian)

Youth activists Moaz Abd El-Kareem, Sally Moore and Mohammed Abbas. Photo: Platon (Human Rights Watch)

On a sweltering night shortly before the start of Ramadan, the Muslim Brotherhood convened a political rally in the Nile Delta town of Shibin El-Kom. Most Cairenes wouldn’t even drive through the capital of Monufiaprovince unless they had family there. Agriculture is the only business in this marshy area at the start of the maze of canals and river branches that marks Egypt‘s breadbasket. The peasants, or fellaheen, who till the land are religious, nationalistic and socially conservative. The elites who rule Egypt have their roots in such places – the previous two presidents, Hosni Mubarak and Anwar Sadat, were born in Monufia – but once in power dismiss them as backwaters. Among the nation’s power players, though, the Muslim Brothers are an exception; their leadership comes largely from the educated working classes and boasts an easy familiarity with the fellaheen.

The rally in Shibin El-Kom officially launched the parliamentary election campaign of the Muslim Brotherhood’s new political wing, the Freedom And Justice party. Informally, the Islamists were striving to distinguish themselves from the revolutionaries who had upended the country’s crusty political order in January and who were again occupying Tahrir Square – and naming the Muslim Brotherhood among their counter-revolutionary enemies. Activists had set up a utopian tent city in Cairo’s central plaza, trumpeting their vision for a civil state and decrying the fact that half a year after Mubarak’s resignation the nation was still governed by a military dictatorship. After a month in the square, however, they were drawing fewer people every day, their message drowning in a stream of dictates from an increasingly nasty Military Council and criticism from increasingly acerbic Islamists.

The scene couldn’t have looked more different in the Delta. The Brotherhood had selected for its rally a dirt track off the town’s main bypass. Several thousand people, mostly professionals, merchants or farmers, came with their families; volunteers were encouraged to donate blood at ambulances. On stage, party leaders paid tribute to the local families of the martyrs of the revolution – protesters killed in January and February – then moved on to business. A women’s committee chief outlined the jobs women held in the party; a farmer spoke about its agricultural cooperatives. Finally, party head Mohammed Morsy gave a rousing speech. “The people gave their revolution to the military to protect,” he thundered. “The only legitimacy in this country today comes from the people.” In closing, he ordered his audience to demonstrate the party’s discipline and breadth in their neighbourhoods – by picking up the garbage.

Six months after Mubarak surrendered to millions of Egyptians, the same generals still rule. Arbitrary detention and allegations of torture are commonplace, if less widespread than before. State media still demonises critics of the junta, and the military – without public consultation – will decide exactly what process is supposed to lead to democratic elections and a civilian government. Reformers and revolutionaries fear the military, stronger now than under Mubarak, will outmanoeuvre them. And they fear Islamists will sweep the elections and control the writing of a new constitution, leading to a democratic Egypt that’s neither secular nor liberal.

In short, the problem is this: idealistic revolutionaries dream of an Arab democracy that reflects popular values but opens its arms to Muslims, Christians and people who want a secular state. But they look outgunned by the religious right, which wants majority rule, and whose force was apparent on the last Friday in July when a million people flooded Tahrir Square demanding “Islamic state, not civil”. Above the fray, the generals rejoiced: the more profound the divisions between Islamist and secular opposition, the better for them.

The summertime scenes in Tahrir Square belie the sense that the revolution is increasingly marginalised and under threat. At its core, the revolution represents a force that is much more willing to criticise authority, and tolerate diversity, than perhaps mainstream public opinion. The original throngs that fought riot police drew on at least three major and messily overlapping constituencies. First were the activists – organisers of all political and religious stripes who had come to trust each other over years of strikes, tiny protests and mass arrests. Second were the politicised people previously afraid to challenge the regime but who brought to the protests a distinct agenda – labour unionists, socialists, liberal NGO workers and more conservative religious activists. Finally, there were the hundreds of thousands of angry and apolitical Egyptians sick of Mubarak’s police state.

Outgunned Liberals Stump in Rural Egypt

KAFR EL-SHEIKH, Egypt — Bassem Kamel was running late for the official launch of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party in this provincial capital at the marshy edge of the Nile Delta.

Kamel is a busy man. He sits on the executive committee of the Revolutionary Youth Coalition, the most important forum representing the organizations that sparked Egypt’s January 25 uprising. He’s a key organizer of Mohammed El-Baradei’s presidential campaign. And he’s a founder, and likely parliamentary candidate, for the Social Democratic Party, one of the most compelling of the new parties that can credibly lay claim to the liberal Revolutionary political center.

On this summer night, however, Kamel’s top priority was this remote farming entrepôt near the Mediterranean coast, where his party hopes to challenge the better-established Islamist parties in the upcoming elections with a message of equality, social justice, and prosperity delivered by a transparent, liberal, civilian-controlled, secular state.

If liberals are to have any traction in Egypt after Mubarak, they’re going to have to win a following in neglected but not forgotten towns like this one. They’re not shirking from the challenge, and contrary to some caricatures of the revolutionaries here, they haven’t obsessed with the politics of protest and they symbolism of Tahrir Square to the exclusion of other political avenues. How well they’re doing is another matter, and a crucial one for judging the chances of liberalism in Egypt’s next stage.

Islamists always seem to outgun liberals in the contest for mass support, routinely drawing thousands to their rallies, and relying on existing networks of mosques and charities that long pre-date Hosni Mubarak’s resignation.

The Social Democrats, by contrast, operate on a shoestring and are starting from zero. Kamel and the other founders have drafted a careful platform that adapts the vision of Europe’s social democrats to Egypt’s vast population, endemic poverty, and state-dominated economy. Put simply, the Social Democrats want to help the poor without stifling the market; they want to create wealth as well as redistribute it. Add to the mix a deep respect for pluralism, religious freedom and individual liberties, and you’ve got a potent – if not yet popular – liberal brew.

Mubarak on Trial

Lots of good copy out of Cairo on the opening day of Mubarak’s trial. What a sight! The indispensible leader on a hospital bed, in a cage, flanked by his sons and six of his top cops. Anthony Shadid captures the scene gracefully (and his set-up piece is also worth reading).

WNYC’s The Takeaway had me on this morning to talk about the trial; you can listen here.

UPDATE:

WBUR’s Here & Now talked to Mahmoud Salem (author of the Sandmonkey blog) and then me at noon Eastern time, mainly about the prospect and peril of Egypt’s revolution turning to violence.

Mubarak Trial: Justice or Revenge?

Hosni Mubarak liked to imply that he united otherwise ungovernable Egyptians under his rule by sheer force of will. As he makes his debut in the defendant’s cage on Wednesday (a barbaric if quite photogenic tradition of the Egyptian justice system), he is bringing together a fractious coalition of Egyptians but not in the manner he intended: baying for his blood.

The most important question, though, isn’t whether Mubarak pays for his past deeds with his life, but how he pays, and for which of his regime’s alleged misdeeds.

A surprising number of people across the spectrum of class and political persuasion told me they’d like to see the dirtiest laundry of Mubarak’s reign aired at trial, followed by a cathartic public execution.

“I want him to hang in Tahrir Square,” a car parts dealer in the Cairo neighborhood of Boulaq told me, adding something blush-worthy about what he’d do to Mubarak if he could get his hands on the former president, which ended with the phrase “I’d make him my bride.”

With more sophisticated language, the revolutionary groups that until recently occupied Tahrir Square have made justice for Mubarak a central demand. Even the military presently ruling Egypt seems to have decided to cast its former chief to the wolves. The judiciary, some of whose key members owe their positions to Mubarak, have expediently and belatedly lent their support to a quick, public trial, perhaps realizing it is the key to their own future viability.

Families of martyrs circulate Tahrir Square demanding an accounting of their missing relatives, like Sayed Goma, 52, who has carried a portrait of his missing teenage son around his neck for the last six months. Nearly crazed with grief, Goma has quit his job as a driver, and talks incessantly of vengeance. “I want them all to go to hell,” he says of Mubarak and his entire ruling apparatus.

But this most unifying demand – that Mubarak be tried for the deaths of 846 or more Egyptians during the uprising that began on January 25 – avoids a reckoning of three decades of complex, nefarious and corrupt authoritarian misrule. A thorough accounting of the Mubarak era would require investigations and likely prosecutions for rampant torture, extrajudicial detention, manipulation of elections, state-sanctioned distortion, blackmail and infiltration of civic institutions ranging from universities and labor unions to professional syndicates and religious organizations. Then there’s the nearly ubiquitous corruption of economic life, in which the first-hand role of Mubarak’s family and inner-circle would barely amount to a prologue.

A sound and thorough judicial inquiry into all these abuses might take years, and certainly would require a renaissance in Egypt’s legal system, which still enjoys wide respect but has been tarnished by decades of crony appointments and arbitrary laws issued by Mubarak and regularly whitewashed by some quarters of the judiciary. It also would require the presumption of innocence for Mubarak, and at least the possibility of guilt for others, including senior military officers, currently enjoying full freedom.

How Mubarak is tried is just as important as what he is tried for. If the former president is charged only for the killing of demonstrators in 2011, or for the illegal enrichment of his nuclear family, the proceedings will tacitly condone the authoritarian system that Mubarak built and the excesses it promoted. Similarly, if the judicial process reeks of vengeance (or to the contrary, if it gives the former president a free pass), it will fail to pave the way toward a new standard of rule of law in Egypt.

A Call to Arms

[Read the original in The Boston Globe.]

CAIRO – When Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak resigned after 18 days of public demonstrations here last winter, Tahrir Square instantly took its place in the world’s iconography of peaceful protest. Young men and women brandishing nothing more lethal than shoes and placards had toppled a dictator. One subversive slogan – “The people want the fall of the regime” – in the mouths of a million people overpowered a merciless police state.

That was half a year ago. Today, Mubarak’s military council runs the country, wielding even more power than before when it had to share authority with the president’s family and civilian inner circle. The military has detained thousands of people after secret trials, accused protesters of sedition, and issued only opaque directives about the country’s path toward a constitution and a new elected civilian government.

As time passes and revolutionary momentum fades in the broader public, a new current of thought is arising among the protesters who still occupy Tahrir Square, demanding civilian rule and accountability for former regime figures. Many are now asking an unsettling question: What if nonviolence isn’t the solution? What if it’s the problem?

“We have not yet had a true revolution,” said Ayman Abouzaid, a 25-year-old cardiologist who has taken part in every stage of the revolution so far. At the start, Abouzaid wholeheartedly embraced nonviolence, but now believes that only armed vigilante attacks will force the regime to purge the secret police and other operatives who still retain their jobs from the Mubarak era. “We need to take our rights with our own hands,” he says.

Among the dedicated core of Egyptian street activists who have been at the forefront of the protests since the beginning, an increasing number have begun to argue that a regime steeped in violence will respond only to force. Egypt’s revolution appeared nonviolent, they argue, only because it wasn’t a revolution at all: it was a quiet military coup that followed the resignation of the president. They cast a glance at nearby Syria and Libya, still racked by sustained violent revolts against their authoritarian leaders, and wonder if that may be what a true revolution looks like.

Leftist political thinkers have turned to the history of the French and Russian Revolutions to argue that a full break from Egypt’s authoritarian past will ultimately require the use of force against the regime. Rank-and-file activists in Tahrir Square invoke a more visceral rule of power, pointing out that riot troops and secret police agents will yield only to the raw strength of popular confrontation.

Egypt’s trajectory is also raising a bigger question about revolutions: Is the modern view of regime change naive and inaccurate, reading too much into the uprisings that swept Eastern Europe after the fall of the Soviet Union? Perhaps these swift and largely peaceful overthrows of former Communist regimes are the exception rather than the rule when it comes to revolution. And if that’s true, Egypt and the other countries driving the Arab Awakening might be heading not toward something better, but something worse.

Nonviolence was philosophically at the heart of Egypt’s revolution since the beginning, and it’s part of why Tahrir Square appealed not only to millions of Egyptians but to so many in the West. January 25 fit nicely on a bumper sticker, signifying a gentle, acceptable kind of popular uprising for the modern age.

But some in Egypt – even among those who don’t want to see a more violent turn now – are already saying we need to see last winter’s events differently. The days that led to Mubarak’s fall were starkly violent, they point out, and the youth who battled their way into Tahrir Square in January did so by overpowering riot police with rocks and Molotov cocktails.

“We did use violence, but we never started violence,” says Alaa Abd El Fattah, an influential labor activist and blogger who has been organizing teach-ins and impromptu conferences on his country’s future. He has pushed a less utopian narrative of the revolution’s origins, although he still believes that protesters today need to remain nonviolent to achieve their goals.

Recent events, however, have convinced some revolutionaries to feel otherwise. Since Mubarak resigned in February, the military has taken charge of internal security and run the show with the same caprice and impunity that characterized the reign of Mubarak’s secret police. Little headway has been made on the demand that unifies protesters and the Egyptian public – that police officers who killed or abused civilians under the old regime be removed from their jobs and held accountable. Egyptian citizens who express political dissent are still routinely denounced on state-run television as foreign agents and spies. And on June 28, the riot police deployed for the first time since Mubarak left office, and with apparent relish pummeled demonstrators with tear gas, birdshot, and plastic bullets. YouTube videos capture police in and out of uniform taunting demonstrators with swords and sarcastically chanting one of the uprising’s own slogans back to them: “Raise your head, you’re Egyptian.”

Since then, a persistent chorus has started to call for a more violent challenge to the regime’s behavior. Core activists in Tahrir Square point out that it was the brute force of people fighting riot police in January that startled the regime and forced Mubarak’s resignation; they argue that the mostly peaceful manifestations since then have allowed the military dictatorship to survive intact. During the initial uprising, Abouzaid, the cardiologist, slept in front of Egyptian Army tanks to stop them advancing into Tahrir Square. In the past month he has come to embrace an even more radical approach. “Freedom means death,” Abouzaid said. “That is the equation of a true revolution. You know the police officer who killed your son? You go and kill him.”

Families of those killed in the initial uprising have organized a major pressure campaign to force the government account for the missing and put on trial all the officials involved in attacking demonstrators. Otherwise, they say, they will have every right to take justice into their own hands.

“I want them all to go to hell,” says Sayed Goma, 52, who has been wandering through Tahrir Square since January with a picture of his son, who disappeared in the Jan. 28 clashes with police and is presumed dead. Goma blames the government coroner he accuses of burying unidentified bodies of slain protesters in secret mass graves.

“I will kill his son and not give him the body,” Goma says.

Some street-fight veterans talk of assaulting police stations. Others, including some leaders, say that targeted assassinations of murderous police would spur the regime into action.

The pressure to escalate resistance and employ violence has driven a rift through the disparate coalition of groups still occupying Tahrir Square. Leaders of the April 6 movement, a driving force behind the revolution that commands deep support in working-class areas because of its history of labor activism, have studiously shut down any talk of violent action. April 6 has embraced mainstream positions, even tempering criticism of the military junta while generals were accusing the movement of subversion. But rank-and-file members of the group in Egypt, like Joe Gabra, chafe: “We need to take up arms,” says Gabra, a young organizer. “If you get shot at, this peaceful stuff doesn’t work.”

Even Abd El Fattah, the labor activist and blogger who argues against a revolutionary embrace of violence, muses publicly about using it. “I talk about killing police officers all the time. It’s a fantasy,” he says. “It could solve our problems, but it doesn’t mean I am planning to do it.”

The argument in Tahrir Square is more than a local debate over tactics; it reflects a real divide among political thinkers over what works best when challenging a police state. Though revolutions have long been associated with bloodshed, the astonishing success of the “soft” revolutions of Poland, Czechoslovakia, and later the Ukraine drove much policy and social science research in the post-Cold War era. An influential study published in 2008 made a strong case that peaceful protest was the most effective way to challenge authoritarian regimes. In “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict,” Maria J. Stephan and Erica Chenoweth studied 323 resistance campaigns from 1900 to 2006, and concluded that nonviolent efforts succeeded twice as often as violent ones. Violent crackdowns on peaceful protesters tended to backfire, Stephan and Chenoweth argued, and nonviolent resistance garnered greater international support.

This line of thinking has apparently been compelling not only to academics but to authoritarian rulers in places like China and Russia, who have deployed the full force of the state against even tiny, marginal civil disobedience campaigns, unnerved at the prospect that they might swell into massive nonviolent uprisings. And the philosophy of the Eastern European “velvet” or “color” revolutions infused some of the drivers of the Arab Awakening itself: April 6 leaders even traveled to Europe to meet leaders of Otpor, the nonviolent Serbian movement that overthrew Slobodan Milosevic.

But these gentle revolutions, it turns out, might be exceptions rather than the rule. There’s a backlash among some historians and political scientists that echoes the gut feeling of Egypt’s frustrated revolutionaries. They suggest, sometimes reluctantly, that regimes that insist on ruling by the gun, so to speak, might only be pushed aside by the gun.

Robert Pape, a University of Chicago political scientist, studied terrorist attacks, aerial bombing, and other forms of coercion, and concluded that violence achieves strategic goals far more effectively than peaceful means. Ivan Arreguín-Toft, a political scientist at Boston University, makes a similar argument about the critical role of violence for opposition movements in his book “How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict.”

Some analysts and academics seeking to understand the forces at play in the Arab Awakening look less to the gentle power transitions in contemporary Europe than to the fiery, radical and violent regime changes in Iran in 1979 and France in 1789. These scholars say that the French Revolution, with its guillotine and counterrevolutionary backlash, might be a more useful example of a true break with the past than the measured transitions two centuries later in Eastern Europe. The French Revolution swept aside an entire system, not only removing the royal family from power but smashing the feudal economy and the monarchical philosophy on which it was built. Arab activists have also noted that Iran’s revolution – whose theocratic aims they do not share – successfully remade the entire state because it brooked no dissent and warmly embraced violent tactics.

The gentler Eastern European uprisings, by contrast, are now seen as a different kind of regime change: not so much revolutions as restorations, a return to a broader European trajectory interrupted by Soviet domination at the end of World War II. Other uprisings, like the “people power” waves that overthrew dictators in the Philippines and Indonesia, largely avoided violence because they demanded incremental reform rather than the toppling of an entire system, and the military didn’t defend the regime. It is usually when the dictator’s ruling apparatus refuses any compromise at all that reformist opposition morphs into violent revolution – as is the case today in Syria, where rebellion is veering toward open conflict, and Libya, fully in the throes of civil war. Most Egyptians, it is clear from the public conversation here, would prefer the smoother kind of transition: a revolution without the sturm und drang. The question is whether that will be enough to unseat the military.

Theda Skocpol, the Harvard sociologist who redefined the study of comparative revolutions, cautioned that “there is no one ‘paradigm’ for a revolution.”

“Egypt seems to me to be going through a kind of political change, but not a full-blown revolution,” Skocpol says. With the army still in charge, she argues, nonviolent protests may yet be the most effective approach, especially since the military establishment, which depends on US support, will be sensitive to international public opinion.

Back in Tahrir Square, conversations are rife with historical analogies, as activists trade theories about revolutions past, in France, Russia, and Eastern Europe, and ongoing fights elsewhere in the Arab world.

“We need patience,” Sayed Radwan, a 52-year-old airline counter representative, said on a recent afternoon. “The French Revolution took 30 years.”

“Yes,” snapped his friend, “but first, they killed all the leaders.”

Judging by the size of the crowd…

… Egypt’s secular liberals are in trouble. I have a lot of reporting on the subject to sift through, but a few weeks of immersion in the burgeoning political party scene here suggest that the new liberal parties have a lot of catching up to do. Perhaps a prohibitive amount.

Above is the crowd at the founding meeting of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party in Kafr El Sheikh, a provincial city in the Nile Delta, earlier this month. It numbered fewer than 200, probably closer to 100 by the end.

Below is a rally last night organized in another Delta city, Shibin El Kom, by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party. The crowd numbered about 2,000, all of whom listened rapt until the end of the three-hour event, replete with detailed policy plans and instructions for cadres. If these number are any indication (and some smart people say they’re not), the Brotherhood is running far stronger than anyone else.

Egyptian Doctor on Hunger Strike

Dr. Ayman Abouzaid hospitalized in Sharm El Sheikh, where he demands a floor all to himself like Hosni Mubarak. Photo courtesy of Ayman Abouzaid.

Crazy times call for crazy gestures, and Ayman Abouzaid has found himself playing an increasingly high-risk game of chicken with the Egyptian regime. The young cardiologist jumped out of his apolitical cocoon right into the roiling waters of revolution in January. When he wasn’t on call at the Qasr Ayni hospital, he spent his nights sleeping under the treads of Egyptian army tanks to prevent them moving into Tahrir Square.

That sentiment kept him on the streets for weeks then, and kept him shouting and railing about all the enduring injustices of his system, from the impunity still enjoyed by Hosni Mubarak’s coterie to the petty corruption that he says allowed supervisors at Qasr Ayni to falsify autopsy results on protesters murdered by the police.

Ayman Abouzaid’s rage might yet make him a bellwether of where Egypt’s revolution is headed now.

At 25, he had given up on a future in Egypt and was looking to continue his medical training in Germany. But the revolution watered anew his love for country. When I first met him, arrayed with a few dozen men beneath a tank by the Egyptian Museum, he was nearly euphoric. It was a few days before Mubarak acceded to people power and resigned, but Abouzaid already was convinced it would happen.

“The people here will only leave in two situations,” he told me. “When Hosni Mubarak and the National Democratic Party are judged and executed, or we all have to be dead.”

The Split in April 6

On his blog yesterday, CFR’s Steven Cook revealed that a founder of the April 6 youth movement in Egypt, Ahmed Maher, was working with a Beverly Hills public relations company. Although the company appears to be donating its work, Cook speculates April 6 will look out of touch, vainly self-promotional, or even tainted as too tied to foreign interests.

In fact, such accusations have been levied at Maher, a dedicated movement activist whose early work in 2008 to organize striking textile workers was a pivotal step in Egypt’s path to revolution. April 6 has become a formidable movement with lots of grassroots urban activists. They’ve had street muscle and staying power since January, and often appear more in touch with mainstream Egyptian public opinion than other revolutionary activists, who can come across as too intellectual and even at times, as elitist. Maher was featured in a PBS Frontline documentary, and has been one of the revolution’s media stars.

In the last few months, a rift emerged between Maher’s circle and other April 6 leaders. The movement now has effectively split, although there hasn’t been a public announcement of it and both factions use similar logos and names. The breakaway faction, which calls itself the April 6 Movement and is prioritizing protest and political mobilization, appears by far larger. “There was no internal democracy,” said Tarek El-Khouly, one of the leaders. “There was no transparency. [Ahmed Maher] wouldn’t tell us if he was getting foreign funds.”

Ahmed Maher and his associates are known in the activist community now as the April 6 foundation or NGO, and are focusing more on public education and outreach about the democratic process.

The split says something about the entropy and divisiveness among Egypt’s activists, whose courage and persistence is sadly, but not unexpectedly, matched by interpersonal rivalries.

There’s also a long history of tarnishing activists and dissidents as foreign agents; it was a common slander tactic of the Mubarak regime, and it resonates with the widespread xenophobia and paranoia in Egypt (fueled of course by the long track record of foreign manipulation of Egyptian politics).

One-Man Tent, Tahrir version

How to keep cool in the middle of a day-long protest in a shadeless square with the sun pushing temperatures to 100 degree Fahrenheit? Here was one man’s resourceful solution on July 8.

Reinvigorating Egypt’s Revolution

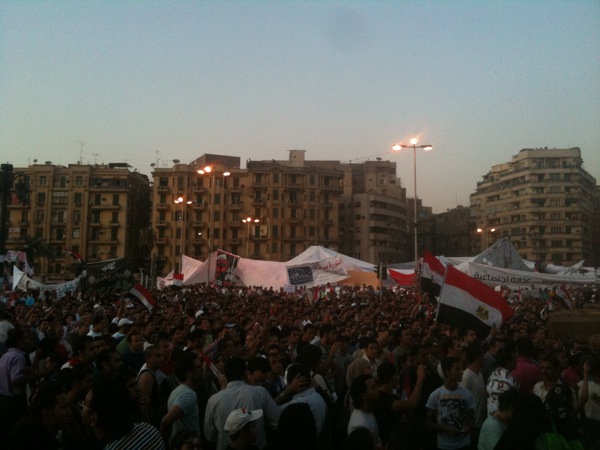

CAIRO, Egypt — Friday’s “Day of Determination” (or “Day of Persistence”) continued overnight and into Saturday as a sit-in in Tahrir Square. It was the largest since President Hosni Mubarak stepped down, and it marked a sort of inflection point for the popular uprising that began on January 25.

For the first time since mid-February, the crowd filled the entire square, and drew scores of regular folk who wouldn’t normally define themselves as political activists. The demonstration swelled to revolutionary size, to a large extent, because its organizers consciously eschewed politics. Instead they resorted to a lowest-common denominator appeal to prosecute Hosni Mubarak and his henchmen. Justice for the crimes of the past, and for the crimes that continue, including police brutality, unaccountable government, and military detentions of protesters. Two words echoed above all: justice, and revenge.

That simple call galvanized the protest, although to some was its Achilles heel.

“The blood of the martyrs won’t be wasted,” the crowds chanted. Protesters carried pictures of Hosni Mubarak hanging from a noose (a common motif, also stenciled on walls around Tahrir).

A performer named Waleed Sheikh held a Mubarak marionette wearing the traditional red Egyptian death row suit, a star of David on the front. “I am manipulating him like he used to manipulate us!” Waleed said as he made the Mubarak doll dance, to the wild applause of onlookers.

Many of those in crowd said they hadn’t joined a protest since February, but were galvanized by the ruling junta’s foot-dragging on trials for Mubarak cronies and on police reform.

“I thought the government would be purified after the revolution,” said chemist Mahmoud Fathy, 29. “They are trying to outsmart the revolution, to outwait us and change nothing.”

Day of Persistence on The World

Marco Werman asks me about today’s protests in Tahrir on The World. I’ll post more about this later, but the crowd today was larger and more harmonious than at any point since February, when President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. It certainly marked some kind of turning point in terms of popular impatience with the general who run Egypt, and it might signal something important about the enduring appeal of revolution and the failure, so far, of opposition politics to capture Egypt’s imagination.

Pushing the Boundaries

CAIRO, Egypt — On the fourth day of publication, Ibrahim Eissa bounds into the newsroom of Tahrirnewspaper, his latest anti-establishment venture and quite literally the offspring of Egypt’s January uprising. It’s midday, and he’s ready to plough through the day’s diet of news stories, opinion columns, and satirical cartoons that seem poised to make this tabloid the paper of record for the demographic known here simply as “the youth of the revolution.”

He’s wearing his trademark brown suspenders, and his trapezoidal mustache twitches as he hails the receptionist, the foreign news editor, and the managing editor.

“I’m the oldest person here,” proclaims Eissa, who appears also to be the most energetic. He later explains that youthfulness is a point of pride in Egypt’s gerontocracy, where the octogenarian president appointed septuagenarian deputies to run his police state. Field Marshal Mohammed Tantawi, Egypt’s current leader, is 75.

Tahrir launched at the beginning of July after months of planning. The paper is determined to challenge authoritarianism and corruption, and to cross whatever red lines Egypt’s rulers try to draw around a free press.

“Before, Mubarak was the red line,” Eissa says as he discusses the paper in his narrow corner office, as editors parade through. “Now the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces has replaced Mubarak. They don’t want anyone to criticize them directly.”

Eissa still tends the most boisterous patch of Egypt’s still-tender garden of free expression. At 45, the veteran editor might boast the toughest hide of any Egyptian journalist. During the long tenure of President Hosni Mubarak, Eissa was fired from nearly a dozen jobs and dashed all the regime’s taboos. In 2007, he was sentenced to a year in prison for writing about Mubarak’s failing health, which was treated as a state secret. (The sentence later was overturned on appeal, but the case successfully muzzled the Egyptian press.) For five years, he ran the liveliest paper in Egypt, Al Dostour (“The Constitution”), building it into enough of a threat that in October 2010 Mubarak had a crony buy the paper and fire Eissa the next day.

Read the rest in The Atlantic.

Back in Tahrir for Tear Gas and Detention

I returned to Egypt on Tuesday, escaping the tear gas and riots in Athens for the Cairene edition. I followed the parallel clashes on Twitter, and then headed out to Tahrir. The scene felt different than in February — a somewhat hard to parse mix of earnest protesters, activists, disenfranchised Egyptians, thugs, and soccer hooligans. As I tried to interview the father of a martyr from January, a pair of middle-aged men confronted me, with a mix of bullying, menace and manhandling that I’ve come to associate with regime figures or their henchmen. “How do we know you’re not a Jew?” one of them demanded. He had white hair and wore a light blue suit. With prompting from the crowd that assembled he demanded my Egyptian press card, which he grabbed, crumpled up, and stuffed in his pocket. After some shoving and shouting, he resolved to present me to the police — obviously, he said, I was a spy and not a journalist. (You can see him in the middle of the group pictured here; I snapped this with my iPhone while the citizens brigade contemplated what to do with me.)

The police officers at Marouf Street were unimpressed. They sent the man and his small mob on their way, and after a short time, the duty officer turned to me. “Imshee,” he said, “leave”* — one of the chants the crowds in Tahrir used to direct at Hosni Mubarak when he still was president.

You can read more detail about the day in my dispatch at The Atlantic.

CAIRO, Egypt — The city is combustible. On Tuesday night, seemingly out of nowhere, fighting engulfed Cairo at a pitch not seen since the Days of Rage in January and February that forced President Hosni Mubarak to resign.

A group of families had gathered in another neighborhood to celebrate the martyrs killed during the revolution; no one knows who organized the event and who attended. No one knows exactly what happened next either — just that police tangled with the families, who then decided to march on the Ministry of the Interior in downtown Cairo. After nightfall, the fighting took on a momentum of its own. Hundreds of demonstrators massed at the interior ministry and later in Tahrir Square. Riot police shot tear gas and, according to protesters, rubber bullets. Demonstrators threw rocks and Molotov cocktails. The fighting surged on throughout the night, unabated.

By noon on Wednesday, several thousands of demonstrators were still battling the riot police. Reinforcements had arrived, including 20 ambulances. The fighting raged on Mohammed Mahmoud, the spur street off the southern end of Tahrir Square leading to the interior ministry. Men on ambulances ferried the hundreds of wounded back to the ambulances. The sting of tear gas stretched half a mile from the clashes, enveloping the entire square. Helpful men offered vinegar and Kleenex to alleviate the pain of inhaling the gas.

I was eager to talk to some of the martyrs’ families, find out how the whole melee began, and see how they felt it would affect their cause. Men and women huddled in knots, ignoring the tear gas, arguing about whether these clashes would undermine the revolution by alienating a wider Egyptian public that is tiring of protests. None of them were relatives of martyrs. Many of them were wary.

“I’ve been in Tahrir since January 25, and a lot of the faces I see out here today are not the usual faces,” said a 27-year-old accountant named Mahmoud. “A lot of them look like thugs.”

*In the original post, I had incorrectly written “emsha” for “imshee.”

Discouraging Lessons of History

CAIRO, Egypt — Old ways die hard.

It only requires a quick glance at the new Egyptian junta — as most of the country’s citizens see it — to understand how the military rulers see their inviolable position. On its Facebook page, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces issues terse directives. Egyptian citizens post comments by the tens of the thousands, but there’s never any response. The military’s high-handed public outreach is similarly one-sided. One general appears on television to read the same directives, stony-faced, to a camera. And every now and again, the military stages public “dialogues,” which come across, intentionally or not, as patronizing lectures.

How does the military view its future in Egypt? What internal dynamics are shaping the military’s political strategy, which could in large part determine whether February’s revolution is a success? Within the officer corps, there are diverse views as to how much power the Egyptian army should wield, and how much it should yield to elected civilians.

It can be difficult to get answers to these questions from the military, perhaps in part because they themselves don’t yet know. So I’ve turned to reading history, hoping to find answers there, and was struck once again by the tight congruity between present-day Egypt and the critical points it has experienced over the last century and a half. During much of that time, Egypt has politically lain fallow, either because of self-induced paralysis as during Hosni Mubarak’s rule or long periods of colonial subjugation, as during the era of the British-orchestrated Veiled Protectorate.