A General’s Unnerving Visit

The Atlantic has posted my piece about Tahrir today.

CAIRO, Egypt — Army General Hassan Ruweini came to the barricades of Tahrir Square on Saturday afternoon for a listening tour. He wanted to hear from the protesters, and then he wanted them to shut up and listen. “It’s time for life to go back to normal,” he said. “You can express yourselves without interfering with others.”

The general wanted to clear the burnt cars, corrugated metal sheets, and requisitioned construction material that had kept police, thugs, and now the comparatively benign military out of the free zone declared by anti-regime activists in Tahrir Square on Jan. 25 and held at great cost ever since.

Now Old Egypt had come to call, bringing a kindler, gentler tone along with the old familiar menacing grip.

“We won’t go until he goes,” the crowd chanted in response, referring to President Hosni Mubarak. Demonstrators refused to let General Ruweini move toward the square, linking arms in a human chain to block his way.

Part negotiation, part restrained violence, part intimidation, the choreographed encounter between the general and the protesters was a microcosm of the Egypt emerging from the turmoil of the last week. A faltering state authority is groping for new ways to impose its will; a hardening popular movement is learning how much power it really wields. They are circling each other, risking deadly clashes at every turn.

In this process, some truths once considered absolute have perished summarily, including the impunity of the police and the infallibility of Mubarak. Others are quietly reasserting themselves: many Egyptians are accustomed to order, state security owns most of the country’s streets, and force often carries the day.

Read the rest here.

Tahrir Today

On my first day in Tahrir Square, General Hassan Ruweini broke through the barricades in one-man charm and intimidation offense, which I’ve written a piece about that should be posted shortly on TheAtlantic.com. Here’s what it looked like from my vantage point as General Ruweini lectured the hostile crowd, and below, the northernmost barricade.

Fresh Air

Terry Gross interviewed me on Fresh Air today about the events in Egypt and their potential to create new space in Arab politics. From the Fresh Air website:

All of our assumptions about the Arab world have been turned on their heads in the past month, says veteran Middle East correspondent Thanassis Cambanis.

“Everything that the experts say and everything that the activists and politicians have taken for granted for a generation, at least, is really off the table,” he tells Fresh Air‘s Terry Gross. “What’s been happening, first in Lebanon and then in Tunisia and now in Egypt and who knows further afield, suggests that new forces have been unleashed and we have no idea where they might lead and what new dynamics they might create.”

On Wednesday’s Fresh Air, Cambanis puts what has been going on in Egypt in a historical context — and explains the rising influence of the political party Hezbollah in the region. He says the recent explosion of popular anger and activism in Egypt opens up the possibility for a new political movement — one not endorsed by autocratic regimes or rooted in Hezbollah’s Islamist ideology.

“There are a lot of people, both dispossessed and powerful, who want dignity but they don’t necessarily want endless war — which is what the Hezbollah school of thought advocates,” he says. “I think they would be hungry for, and very receptive to, an Egypt-centered political movement that talks about Arab empowerment but not endless war.”

Waiting for Mubarak

Mubarak’s speech tonight eerily evoked the tone of Iraqi Baathists in the spring of 2003. Even after Saddam had fled and American troops had occupied Iraq, I met Baathists in Baghdad who spoke to me with supreme confidence about their natural role running Iraq. They had no doubt that they would remain in charge, one way or another. It took them years to realize how much their nation had changed – and that the Iraqi people didn’t want to be ruled by some reconstituted version of Saddam’s regime.

Mubarak’s speech tonight eerily evoked the tone of Iraqi Baathists in the spring of 2003. Even after Saddam had fled and American troops had occupied Iraq, I met Baathists in Baghdad who spoke to me with supreme confidence about their natural role running Iraq. They had no doubt that they would remain in charge, one way or another. It took them years to realize how much their nation had changed – and that the Iraqi people didn’t want to be ruled by some reconstituted version of Saddam’s regime.

I don’t mean to compare Saddam to Mubarak, only to point out the parallels in the process of regime detachment, teetering, and imminent implosion. It’s possible that Mubarak’s advisers have shielded him from an accurate assessment of the events of the last week, and that he has a distorted picture of the size of the crowds, their sentiment, and the dim reputation of the Egyptian state among its own people.

For three decades, Mubarak has successfully convinced some of Egypt’s elites, and much of the West, that the only choice lay between his dictatorship and Islamic fundamentalists. Mubarak offered continuity and cooperation for the United States, but little else, since Egypt under NDP rule shrank in every indicator (political influence, economic growth, regional influence). The other option in this belabored formulation was a violent, extremist Islamist Egypt ruled by the likes of Ayman Zawahiri.

In reality, however, there was no political space in Egypt whatsoever beyond the platform the regime accorded itself and its organs. The Muslim Brotherhood and the officially sanctioned opposition were only able to function in public within the limited confines permitted by the regime. Consequently, their political development was stymied.

Right now, political space has opened for the first time. The loudest voices within it come from unknown Egyptians, and not from the activists and cadres who have toiled for years in the state-sanctioned opposition. Their preferences are little understood, and perhaps not yet fully developed. They want Mubarak gone, and they seem to want his coterie out as well. They want some form of accountability. Beyond that, we have no idea if they’re interested in forming new political movements and ideologies, or whether they will forge a new way in Arab politics, some platform of ideas distinct from Islamism and secular statist autocracy. If they do, we can guess it will sound less friendly to Washington and Israel than Mubarak’s regime did, and we can also guess it might have a more religious and populist tone. Beyond that, though, there’s little yet to suggest what real representative politics will sound like, or what kind of government might take shape, or what its foreign policy might be.

There is reason to believe, however, that a post-Mubarak and post-Days of Rage Egypt might be able to deliver some improvement in living conditions, morale and perhaps regional leadership to the Egyptian people — if only by dint of trying. And so far, there’s no reason to expect that the mass of protesters, and the inchoate political realm coalescing in its wake, will agitate for war and instability. They seem bent on living better than they have under Mubarak’s rule, not on recreating the 1960s and 1970s.

Things We Don’t Know

The unraveling of Mubarak’s regime has proceeded at a tremendously exciting pace over the weekend, spawning news, uncertainty, as well as a layer of ideologically-motivated posturing in the U.S. that is only confusing our still-murky view of the situation.

The unraveling of Mubarak’s regime has proceeded at a tremendously exciting pace over the weekend, spawning news, uncertainty, as well as a layer of ideologically-motivated posturing in the U.S. that is only confusing our still-murky view of the situation.

We still don’t have a full picture of exactly what’s happening now in Egypt. We don’t know what’s happening inside the military and inside the top levels of the regime. We don’t know exactly what kind of schemes the police have implemented, although there’s evidence of undercover cops looting and trying to provoke chaos. We don’t know how motivated the protesters are to organize for the long term – although we do know their actions until now have defied almost all expert predictions. We don’t know how many people have been killed and arrested. And we hardly know what’s happened beyond Cairo and Alexandria. We don’t know how it will all turn out.

Given that vast uncertainty, it’s all the more important that we don’t let ideologues exaggerate what we do know, or paint false pictures of the players involved. We do know that almost all of the protests have eschewed the language of Islamism, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the weak establishment opposition parties. We do know that most Egyptians don’t consider Mohammed ElBaradei an inspiring or charismatic figure, and that until this weekend most activists (secular as well as Islamists) viewed his year-long debut in Egyptian politics with disappointment or even frustration. We know that the Muslim Brotherhood has been reluctant to challenge Mubarak’s regime – declining to join bolder secular parties in boycotting last fall’s parliamentary elections, and sitting out the first rounds of the “Days of Anger” this January. Finally, we know that Egypt’s suffocated civil society boasts only a few institutions with national organizational reach: the military, the state security organs, the ruling National Democratic Party, the Muslim Brotherhood, and possibly the Coptic church. Even if they play little or no role in the protests, they’ll be positioned to capitalize most quickly on a post-Mubarak order.

When an authoritarian state collapses, it’s wise to watch players with existing capacity. It’s even wiser to recall that all bets are off. Once-omnipotent secret police can vanish in a day (it happened in Iraq in 2003). New populist parties can quickly emerge. Dormant or smothered institutions like labor unions can quickly reemerge with vigor, and new political parties can spring up to tap public sentiment. Forces like the popular committees organizing to protect Egyptian neighborhoods from looters and the police could easily morph into a potent political force.

So ignore anyone who tries to paint the situation today in Egypt as a simple struggle between a moderate authoritarian regime led by Mubarak and a fanatical Muslim Brotherhood poised to lead Egypt into war with Israel. That regime, as it existed until last week, will be forever changed by the Days of Rage if it survives in some form or another under President Suleiman. Multiple unknowns surround a Muslim Brotherhood that has acted anything but radical in the last three decades, but that’s largely beside the point; the Brothers simply don’t have the numbers or the dynamism to take over this popular revolt. They’ll be a key stakeholder in any new order, but there’s no evidence to suggest they’ll play a dominant role. The military will still be there next month. So will the labor unions, and so will the privileged class that backed Mubarak’s regime and which in Egypt’s next iteration will still channel much of its economic and political power. Egypt’s history of secular nationalism will surely shape events, as will a surging popular will that until last week was almost entirely a mystery.

History’s Side in Egypt

The popular uprising in Egypt today will conclusively change the political dynamics in the most populous Arab country, no matter what the short term outcome. Hosni Mubarak might hang on to the presidency for some time, but the parameters have radically changed. (I can’t take my eyes off Al Jazeera.)

The popular uprising in Egypt today will conclusively change the political dynamics in the most populous Arab country, no matter what the short term outcome. Hosni Mubarak might hang on to the presidency for some time, but the parameters have radically changed. (I can’t take my eyes off Al Jazeera.)

In August and September, all the Egyptians I interviewed about their country after Mubarak ruled out mass protests as even a remote possibility – especially mass protests not organized by the Muslim Brotherhood.

But that’s exactly what we’ve seen now; tens of thousands of people, maybe more, in virtually every major Egyptian city, willing to march and knock heads and risk death to call for an end to Mubarak’s rule. They’re not doing it under the banner of the Muslim Brothers or of the small, organized secular opposition.

So one shibboleth of Egyptian politics has been cast aside: the Egyptian people are capable of revolt.

What follows will depend on many factors: the endurance and persistence of the protestors; the choices of influential politicians, in and out of the regime; and most of all, I think, the choices the military makes.

Right now, police and intelligence run Mubarak’s police state. The military governs its own fiefdom, and considers itself the steward of the nation’s sovereignty. As retired General Hosam Sowilam told me this summer, in a time of transition the military “shall obey the president because he will be accepted by the people. But we will not accept any interference by the political parties into our military affairs.”

If the people withdraw their support from Mubarak, I guess the military will see its advantage in standing with them and not with the regime. In terms of bald self-interest, the military will want to maximize its influence with whomever follows Mubarak. That’s similar to the choice Tunisia’s military made.

A handful of power centers can play a role in crafting an alternative to Mubarak’s rule: Egypt’s intelligence chief; the military; the interior ministry; and to a lesser extent the institutions of civil society, both pro- and anti-regime: the NDP, the Muslim Brotherhood, the secular opposition parties, the protest movement, ElBaradei’s organization. Only the military has the weight to tilt the balance on its own.

Sharing the Nile

Especially in the Middle East, there are always people uttering dark apocalyptic warnings about the coming water wars. Competition over scarce oil is nothing, the thinking goes, compared to what people and their governments will do when water starts running out.

Especially in the Middle East, there are always people uttering dark apocalyptic warnings about the coming water wars. Competition over scarce oil is nothing, the thinking goes, compared to what people and their governments will do when water starts running out.

Scarcity, of course, is nothing new, and “water wars” have already been happening for some time. They’re not cataclysmic (and usually not entirely binary) like wars over a specific piece of land, which either you control, or you don’t. Israel and Lebanon have fought over a contested border with at least one eye on the watersheds and rivers on both sides. Iraq, Syria and Turkey have had problems over the Tigris and Euphrates, the present result being that the two great rivers are muddy trickles by the time they reach southern Iraq. I imagine there are countless other examples.

Egypt is now contending with the end of its own era of water abundance. A colonial-era treaty gave Egypt and Sudan 80 percent of Nile’s water. The upstream African countries are now sufficiently stable — and eager for economic development — that they have challenged this arrangement. Negotiations collapsed and now Egypt has until next May to rejoin talks, or face a new regime designed by the upstream nations in the Nile watershed.

This isn’t the kind of conflict that I would expect to spark a traditional war, but it’s uncharted, and fascinating territory. You can read more in my story from this Sunday’s New York Times.

One place to begin to understand why this parched country has nearly ruptured relations with its upstream neighbors on the Nile is ankle-deep in mud in the cotton and maize fields of Mohammed Abdallah Sharkawi. The price he pays for the precious resource flooding his farm? Nothing.

“Thanks be to God,” Mr. Sharkawi said of the Nile River water. He raised his hands to the sky, then gestured toward a state functionary visiting his farm. “Everything is from God, and from the ministry.”

But perhaps not for much longer. Upstream countries, looking to right what they say are historic wrongs, have joined in an attempt to break Egypt and Sudan’s near-monopoly on the water, threatening a crisis that Egyptian experts said could, at its most extreme, lead to war.

“Not only is Egypt the gift of the Nile, this is a country that is almost completely dependent on Nile water resources,” said a spokesman for the Egyptian Foreign Ministry, Hossam Zaki. “We have a growing population and growing needs. There is no way we can accept this kind of threat.”

Egypt’s military II

Michael Hanna elaborates his views on the Egyptian military’s role in a presidential transition at Democracy Arsenal. He brings up some of the crucial Mubarak era history (which I didn’t have room for in my NYT piece on the subject), in particular President Mubarak’s 1989 firing of the popular defense minister, Field Marshal Abu Ghazaleh.

Michael Hanna elaborates his views on the Egyptian military’s role in a presidential transition at Democracy Arsenal. He brings up some of the crucial Mubarak era history (which I didn’t have room for in my NYT piece on the subject), in particular President Mubarak’s 1989 firing of the popular defense minister, Field Marshal Abu Ghazaleh.

Michael writes:

It is hard to pinpoint the parameters of the military’s power within Egyptian society at this juncture. Yes, it is the most respected and coherent organization in the country, but Egypt does not fight wars anymore and the military is not involved in the day-to-day of politics. And, it has not been overtly involved in a presidential succession since 1952. While Anwar al-Sadat and Hosni Mubarak were both military men, they were hand-picked as vice-presidents by the president. There was no real process for the military to be involved beyond the sort of informal vetting that might have taken place internally prior to the their appointments. And it is also worth remembering that both al-Sadat and Mubarak were seen as weak figures with no broad popular legitimacy at the time they assumed the presidency, and, yet, the military regime did not attempt to block the ascension of either man to the post.

From an institutionalist perspective, the central question about Egypt remains what pathways exist beyond the mechanisms of power controlled personally by Hosni Mubarak. In the case of the military, it appears that its power must be substantially weaker than it was in 1970 or 1980, but how much weaker, and what control it has, are open and vital questions.

Egypt’s military and its next president

In Sunday’s New York Times I wrote about the Egyptian military’s central role in Egyptian society and what position it might take on the selection of President Hosni Mubarak’s successor. So much is opaque in Egypt’s power structure, and nobody outside Mubarak’s inner sanctum has a clear picture of how anything works, precisely. The retired military officers, opposition leaders, defense consultants, officials, and analysts that I interviewed are either expressing the views of an interested party in the case of the officials and politicians, or are cobbling together theories from a sort of reading of the tea leaves.

In Sunday’s New York Times I wrote about the Egyptian military’s central role in Egyptian society and what position it might take on the selection of President Hosni Mubarak’s successor. So much is opaque in Egypt’s power structure, and nobody outside Mubarak’s inner sanctum has a clear picture of how anything works, precisely. The retired military officers, opposition leaders, defense consultants, officials, and analysts that I interviewed are either expressing the views of an interested party in the case of the officials and politicians, or are cobbling together theories from a sort of reading of the tea leaves.

Even those who believe the military could play an important role have few ideas of how, in practice, the military would exercise that role. Possibilities include:

- A military coup, which most people said was unlikely.

- An expanded role in direct rule, for example by moving to completely shut down the Muslim Brotherhood.

- An internal negotiation with potential successors that protects the military’s continued privileged status

- A tense internal negotiation in which the military does not obtain the assurances it wants, and then seeks to undermine the next president.

- A weak successor who faces a public opinion crisis similar to the uproar in Egypt during the 2008-2009 Gaza war, when Mubarak kept the border closed and essentially sided with Israel over Hamas. In that case, one official source speculated, the military might organize a direct or indirect coup if it fears an ineffective president will be unable to keep domestic order in a time of crisis.

Issandr El Amrani, author of the excellent Arabist blog, gave me a very helpful interview for the story and elaborated further on his blog about the succession prospects. It’s worth reading the whole post, but here’s his thesis:

This situation, in a sense, is ideal for the military, confirming its central role and placing senior military officers — since we are probably talking about that rather than the army as a corporate entity — of winning either way: they will be wooed by Gamal (or any other successor) to support him and, if they decide not to, would easily garner popular support for their own candidate. Should they decide to support Gamal Mubarak, they need do nothing but sit back and allow the process concocted for his “legitimate” election to take place. If they decide against it, it will be most likely a decision taken behind the scenes rather than publicly, with the selection of the candidate taking place in collusion with elements of the ruling party rather than, as some have said, by tanks descending into the streets. A soft coup, if you will, if only because the regime as a whole in Egypt has an interest in preserving the myth of constitutional legitimacy — they would bend the rules, rather than break them altogether.

Stephan Roll, a Berlin-based researcher, also wrote about the military and succession at the Carnegie Endowment’s Arab Reform Bulletin (another version of the essay ran in Al Masry Al Youm’s English edition). He sees the military as a fulcrum point between the ruling party’s old guard and new guard.

For the first time in Egypt’s modern history, the business elite are playing a role in the succession question, but it is still not clear whether that role will be decisive. … So far, the military leadership has kept out of the power struggle between old and new guards inside the party and the government. In general, this neutrality seems to serve the interests of the old guard, as a positive signal by important military officers regarding the new guard and Gamal Mubarak would certainly give them a boost.

As with most of the questions about Mubarak’s successor, the most interesting decisions are likely to be made outside of the public eye, and many of them – like the military’s struggle to maintain its position, or like the ruling party’s internal split between two factions of very rich officials – might take several years to play out. The military has received nearly $40 billion from the United States, which prizes the Egyptian military’s stability and Washington-allied positions. The U.S. also appreciates the Egyptian military’s agreement to stay out of regional affairs, concentrating on defending Egypt’s regime and borders.

The military has much to lose in the transition, these officers and analysts say. Over the years, one-man rule eviscerated Egypt’s civilian institutions, creating a vacuum at the highest levels of government that the military willingly filled. “There aren’t any civilian institutions to fall back on,” said Michael Hanna, a fellow at the Century Foundation who has written about the Egyptian military. “It’s an open question how much power the military has, and they might not even know themselves.”

Brotherhood boycott?

Parliamentary elections are coming up this fall in Egypt, probably in October or November. But the opposition and ruling National Democratic Party alike have their eyes on presidential succession, assuming that President Hosni Mubarak, who is ill and has ruled for 29 years, probably won’t run again in 2011. In that light, the parliamentary elections have become part of the broader political jockeying.

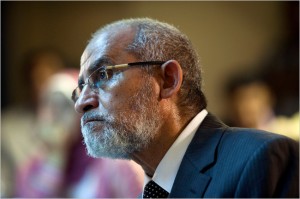

The Muslim Brotherhood commands by far and away the strongest street support among the opposition factions, but it’s a banned society whose parliamentary representatives are technically independents. Meanwhile, the secular opposition parties want to boycott the parliamentary elections to protest the ruling party’s heavy-handed manipulation of the voting process (since the last election, for instance, the government has cancelled the judiciary’s right to oversee polling stations). That’s the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide Mohammed Badie in the picture, getting yelled at by secular opposition leaders during an iftar.

The Brotherhood and the secular National Association for Change are circulating a petition calling on the government to amend the constitution and reform the voting process to allow free and fair elections. It’s a rare instance of the Islamist and secular opposition working together, but even in this arena they’re competing to show who’s stronger. The Brotherhood has collected nearly 700,000 signatures; the National Association for Change only 100,000. You can follow the dueling signature drives on the Brotherhood petition page and the NAC petition page.

You can also read more about the Brotherhood’s internal debate between seeking power and challenging it in my story today in The New York Times.

CAIRO — One by one, the guests at the Muslim Brotherhood’s annual Ramadan iftar banquet strode to the rostrum. A who’s who ofEgypt’s opposition began hectoring the Islamist group. The Brotherhood, they said, by far the most muscular and influential of Egypt’s dissident organizations, should withdraw from the coming parliamentary election that would most certainly be rigged by the authoritarian government.

“Why won’t you take the initiative?” shouted Karima El-Hefnawi, a secular activist and leader of the popular Kifaya protest movement. “Why won’t the Muslim Brotherhood boycott this farce?” The supreme guide of the Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie, sat uncomfortably a few feet to her right.

At the close of the evening, Mr. Badie was noncommittal. The Brotherhood, he said, in time would make up its mind: “Haste makes waste.”

The Muslim Brotherhood is engaged in a delicate dance. Despite all efforts to marginalize the Islamist organization by the United States and its close ally, the Egyptian government, it remains the most credible opposition group. Some of its members want the Brotherhood to fight the government head on, but the Islamist leadership has other goals: freedom to proselytize and organize in neighborhoods, and in the long term, a lifting of the official government ban on its activities.

With an end in sight to President Hosni Mubarak’s 29-year reign, the Brotherhood appears to be signaling its willingness to cut a deal with Mr. Mubarak’s potential successors by not overtly challenging the ruling party’s monopoly on power.

Suburbs a Pharaoh Would Conceive

A few million people have moved to these new cities springing up in the desert outside of Cairo – and they’re nowhere near done. The scale of these places boggles the imagination.

A few million people have moved to these new cities springing up in the desert outside of Cairo – and they’re nowhere near done. The scale of these places boggles the imagination.

Driving around these new developments, we saw billboards for dozens more in the planning stages. I had in mind Max Rodenbeck’s book Cairo: The City Victorious, especially when some people told me these new desert cities would kill Cairo. Max notes that such complaints were rife a millennium ago, and the city somehow survived. A few decades from now, perhaps there won’t be any open desert to speak of between today’s Cairo and its young sibling settlements, 6 October City and New Cairo.

The highway west out of Cairo used to promise relief from the city’s chaos. Past the great pyramids of Giza and a final spasm of traffic, the open desert beckoned, 100 barren miles to the northwest to reach the Mediterranean.

That, at least, was the case until recently. Now, the microbus drivers and commuters driving from Cairo cross 20 miles of nothingness to encounter a new city suddenly springing from the sand. A distressingly familiar jam of cars and a cluster of soaring high-rises herald the metropolis that is designed to relieve pressure on the historic center of Cairo, which city planners have deemed overtaxed beyond repair.

Welcome to the new Cairo, not entirely different from the old one.

Cairo has become so crowded, congested and polluted that the Egyptian government has undertaken a construction project that might have given the Pharaohs pause: building two megacities outside Cairo from scratch. By 2020, planners expect the new satellite cities to house at least a quarter of Cairo’s 20 million residents and many of the government agencies that now have headquarters in the city.

Only a country with a seemingly endless supply of open desert land — and an authoritarian government free to ignore public opinion — could contemplate such a gargantuan undertaking. The government already has moved a few thousand of the city’s poorest residents against their will from illegal slums in central Cairo to housing projects on the periphery.

The Ramadan Moon, Lost in Haze

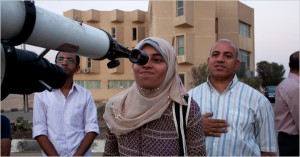

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

“It looks like trouble,” he said.

His deputy, Ahmed Fathy, concurred with a sigh, “I’m afraid we’re not going to see anything tonight.”

The two Egyptian physicists on Tuesday night had a delicate mission: They were charged with providing the scientific imprimatur to the start of the holiest time for Muslims worldwide, the lunar month of Ramadan. Egypt plays a major role in this ritual because it is the seat of Al Azhar, the world’s most prominent Sunni Muslim institution.

According to the Koran, Ramadan, a month of fasting and prayer, begins on the first night that the crescent moon is visible to the naked eye. For centuries, clerics and laymen jostled to spot the Ramadan moon first and often differed. An area with cloudy skies or a different longitude and latitude might declare Ramadan a day or even two later than the rest of the Islamic world.

Modern astronomy long ago took the mystery out of the lunar calendar, whose year lasts some 11 to 12 days less than the Gregorian year used by most non-Islamic countries.

Mr. Mahmoud, the president of Egypt’s National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, publishes a hefty book of tables that lists the precise time and location that the Ramadan moon will appear in various cities throughout the Islamic world.

But science, it seems, can go only so far.

“We know it’s there, but Shariah requires us to see it with our eyes,” Mr. Mahmoud explained. The grand mufti, Egypt’s highest religious authority, awaits a report from Mr. Mahmoud’s team and from a secondary group of spotters organized by the Egyptian National Survey Authority.