Can a Shiite Cleric Pull Iraq Out of the Sectarian Trap?

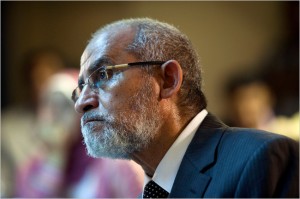

The Shiite cleric Moktada al-Sadr at a demonstration in April against the bombings of Syria by Britain, France and the United States. CreditHaidar Hamdani/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

[Published in The New York Times.]

May 11, 2018

BAGHDAD, Iraq — Iraq’s parliamentary elections on May 12 might seem to offer more of the same because most of the leading candidates and movements have dominated the country’s political life since the United States unseated Saddam Hussein in 2003. But the 44-year-old firebrand Shiite cleric Moktada al-Sadr is leading an encouraging transformation, which could jar Iraq’s politicians out of their sectarian rut.

Mr. Sadr inherited millions of devoted followers from his family of revered religious scholars. Both his father and father-in-law were grand ayatollahs, the highest clerical level of Shiite Islam. He cemented his status by leading a bloody resistance against the American occupation and fighting the United States-allied government in Baghdad. He stubbornly defied foreign intervention, angering both Iran and the United States. He has purged corrupt operatives from his movement.

In the summer of 2015, Mr. Sadr made a potentially historic about-face, uniting with the Iraqi Communist Party and secular civil society groups who were protesting the government’s failure to provide security against the Islamic State or even the basic necessities of life, including jobs and electricity. Together, the new alliance demanded an end to corruption.

Iraq regularly tops world rankings for corruption and suffers endemic unemployment, which is particularly high among youth. When oil prices were high, alleged corruption reached an epic scale, but the people did not receive any benefits in infrastructure, jobs or services. Even vital security services were gutted by no-show jobs, as glaringly revealed when there was no army on hand to stop the Islamic State’s sweep through Mosul and Anbar Province to the gates of Baghdad.T

Corruption has kept Iraqis poor and almost left the country at the mercy of the Islamic State. That is why Mr. Sadr’s slogan “Corruption Is Terrorism” resonates with so many Iraqis. Frustrated with a decade of failures by the rulers in Baghdad, Mr. Sadr embraced civil society groups and their agenda: civic rights, better governance, fair distribution of resources.

An important outcome of Mr. Sadr joining a nonsectarian coalition is a new strain of pluralism and tolerance. The liberating effect is visible in how Iraqis irrespective of class, sectarian and sexual identities can reclaim public spaces without fear.

One spring morning, a group of young men in bouffant hairdos and burgundy and bright green three-piece suits hung out in Qishleh Gardens near Mutanabi Street, the historic gathering place of Baghdad’s poets and intellectuals. In the local context, their attire announced them as gay men. As the men in colorful suits walked around, the clerics recruiting fighters for the Shiite Islamist militias nearby didn’t even throw them a sideways glance.

In the afternoon, some of the men in colorful suits joined an anti-corruption demonstration led by supporters of Mr. Sadr. “We all want to put an end to corruption,” said Mohamed Ismail, a 26-year-old unemployed day laborer. “We are all together.”

Three years earlier, when demagogues loyal to Mr. Sadr were exhorting vigilante attacks on men seen as gay, the pairing would have been unthinkable. Back then, Iraq was riven by difference — the sectarian-hued struggle between the Islamic State, which purported to speak for the Sunnis, and the governments led by Shiite Islamists, who claimed to represent the Shiite majority that had been oppressed under Mr. Saddam.

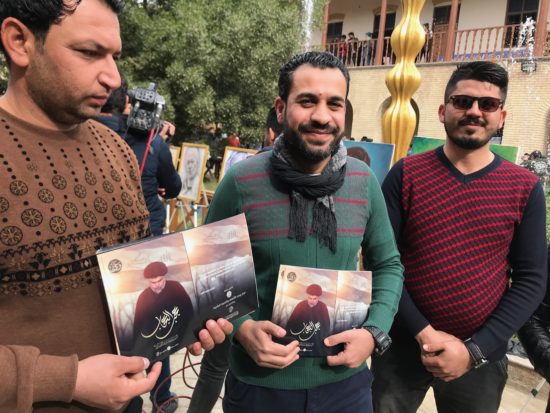

At the Baghdad Cultural Center, adjacent to the Qishleh Gardens, smiling volunteers from Mr. Sadr’s organization distributed fliers with his pronouncements. “Our new goal is to start an independent technocratic government,” said Majid Hamid, a 26-year-old volunteer. “We have no problem with anyone who is Iraqi.” The movement’s emphasis is now on civic questions.

After more than a decade of dominance by Islamist Shiite movements, competitors for power can no longer meaningfully distinguish themselves by their sectarian identity. Self-styled religious parties have been implicated in every major graft scandal, including the mishandling of oil revenue and defense contracts.

In early May, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the most revered cleric in the country, took the unprecedented step of declaring that true believers must not vote along sectarian lines and reminded voters that the clergy has not endorsed any party.

The biggest transformation of all has come during the fight against the Islamic State, which united all manner of Iraqis against nihilist fundamentalists: Shiite and Sunni, Kurd and Arab, Muslim and Christian, religious and secular. Every major electoral faction includes a mix of Iraqis, and the ideas of nationalism and secularism are slowly returning to the Iraqi political sphere.

Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who has roots in the secretive Shiite Islamist Dawa Party, has positioned himself as a nation-builder who thwarted challenges from Sunni supremacists and Kurdish separatists but is willing to accept any patriot as a member of his coalition. Even the most militant Shiite militias have included Sunni partners in their electoral coalitions, including the Fatah Alliance, led by Iran’s fearsome ally, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.

Mr. Sadr has ordered his followers to support the idea of a secular, nationalist government run by “technocrats,” experts who are not career politicians and supposedly will be able to solve Iraq’s ills. He touts the importance of the rule of law and civilian power.

In a series of interviews with politicians, analysts, fighters and citizens, I repeatedly heard that a broad range of Iraqis believe they are at the beginning of a “nationalist moment,” when the country’s political culture might be transformed for the better.

Mr. Sadr has reinvented himself countless times in an erratic political career and can be a fair-weather ally. His appreciation for new, secular allies is not an endorsement of liberalism or progressive views.

But Mr. Sadr has always been a nationalist, committed at least in rhetoric to unifying patriotic Iraqis regardless of sect or ethnicity. His current campaign for a civil, anti-sectarian, reformist government raises hopes and possibilities not experienced in recent Iraqi history. He is changing the terms of political debate.

His political lieutenants say they want to lead the Iraqi government, or else serve as a vigilant parliamentary opposition. Since 2003, every faction that won a share of votes opted to join a broad coalition government and extract its share of the spoils from the public sector trough.

Mr. Sadr shows that a political movement known for the exploits of its militia and corruption can also become a standard-bearer for root-and-branch political reform. His unlikely reformist alliance could give Iraq’s political culture the jolt it needs.

Thanassis Cambanis, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author, most recently, of “Once Upon a Revolution: An Egyptian Story.”

Can Militant Cleric Moqtada al-Sadr Reform Iraq?

[Read the full report at The Century Foundation.]

In the fifteen years since the American invasion toppled Saddam Hussein from power, Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr has distinguished himself from other emerging Iraqi leaders with his endurance, iconoclasm, and unpredictability. He has cut a bedeviling and at times magnetic figure in his country, and he is one of the few sectarian leaders whose popularity has crossed sectarian lines.

Through war, flips of allegiances, involvement in corruption, and military victory and defeat, Sadr has managed to preserve his maverick image as a stubbornly independent man deeply committed to his principles, even as those principles shift over time. Now, with the May 12 Iraqi elections approaching, he is trying to parlay his reputation as a nationalist free-thinker into a movement that can transform Iraq’s political system.

In fact, Sadr has fashioned himself into an unlikely tribune of reform in Iraq. A persistent thorn in the side of foreign powers and Iraqi politicians alike, the graying forty-four-year-old is now trying to radically reshape his country’s politics. He has freshly renounced religious sectarianism, building an alliancewith Communists and secular reform activists.1 He has attacked Iraq’s corrupt spoils system, with slogans such as “corruption is terrorism” that resonate with millions of disenchanted Iraqis. His unorthodox electoral campaign joins Shia partisans, Communist ideologues and some of Baghdad’s secular elite. Sadr’s popularity, hard power, and unifying message make him a direct threat to Iraq’s political class.

Even though his movement is unlikely to win a majority, Sadr’s unique campaign and nationalist-religious-secular alliance has upended nostrums about Iraqi and Middle Eastern politics. He hopes to establish new guiding principles: Sectarian movements can change their politics and become secular and nationalist. Armed militants can take part in electoral politics and government. Sectarian constituencies can embrace nonsectarian principles and support power-sharing and coexistence.

The evolution of Sadr and his movement has unfolded along pragmatic lines, with many flaws and inconsistencies. Nonetheless, Sadr’s political makeover amounts to a groundbreaking and encouraging transformation. It compels other established movements in Iraq to address the core challenges of security and governance, while building trans-sectarian or nationalist coalitions. He sets an example for other leaders and political organizations interested in exiting the confining boxes of sectarianism and patronage and mobilizing broader, more fluid and inclusive idea- or policy-based movements.

The success of Sadr’s approach and platform is more important than that of his candidates. If his coalition is repudiated by voters, or abandons its plans to challenge poor governance, then we can expect more of the dispiriting business-as-usual from Baghdad. But if Sadr follows through after the election and promotes the formation of a platform-based government with a legislative opposition, then we can expect Iraqi politics to enter a new phase, moving away from narrow sectarianism and patronage-only politics. A transition to a government with some technocrat ministers, a real opposition, and some pretense of nonsectarianism is necessary if Iraq is to begin addressing policy problems that affect the stability of the entire Middle East. The most pressing concerns include securing and developing the areas liberated from the Islamic State and reincorporating Sunni Arabs and Kurds into Baghdad’s fold.

This report traces Sadr’s evolution, and both the perils and promises of the road ahead. It is based on more than forty interviews conducted in Iraq in February and March 2018, with support from a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Charismatic Provocateur

Iraqis have long bemoaned a lack of leadership and vision within the ruling class. The melee of corruption and militia-formation that has plagued Iraqi public life since 2003 has featured a parade of politicians and warlords, many of whom have evolved into effective operators. Yet only two indisputably strong, charismatic leaders have distinguished themselves from the fragmentary society of party bosses, warlords, tribal leaders, and the grifters and opportunists who have made deals with the wardens of cash. Those two are both Shia clerics, and no love is lost between them.

The first, and most influential, is Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the single most authoritative leader in Iraq. A cleric of impressive intellect and conservative (rather than radical) nationalist views, Sistani is credited as a moderating force who at times kept Iraq from civil war and at others helped mitigate the scope and damage of sectarian conflict.

The other enduringly powerful figure is the far more junior Sadr, who in the wake of the U.S. invasion emerged as a strong counterpoint to Sistani’s style of leadership and modest ambitions. Sadr lacks the educational pedigree of the ayatollahs who are considered “marjaiya,” or sources of emulation, and whose teachings are followed by millions worldwide. Still, Sadr inherited the millions of passionate followers of his father and uncle, both revered ayatollahs; and he also continued the family feud against Sistani, whom the Sadrs regarded as too timid.

Sadr was not yet thirty years old when the United States invaded Iraq. His family organization already included a nationwide network of staff and offices, and Sadr quickly leveraged these to assemble a committed militia, the Mahdi Army. He emerged as a powerful and unpredictable force—violently opposed to the American occupation as well as to homegrown Sunni extremists.

Although he is a Shia cleric, Sadr made it clear with his rhetoric and style that he was first and foremost an Iraqi nationalist, not beholden to foreign powers, whether Iran, the United States, or another country. From 2004–08, the Mahdi Army forged a fearsome record of violence, fighting at different times against U.S. forces, Sunni sectarians, and fellow Shia movements. His fighters rallied, at least initially, under the banner of resisting the American occupation. In the first years after Saddam’s fall, the Mahdi Army and the Sadrist political organization made symbolic overtures to non-Shia resistance groups and expressed a willingness to ally with Iraqis of any sect or ethnicity (a commitment evident more in rhetoric than in practice). As a result, and especially in the early years following the invasion, Sadr was one of the few militia commanders who enjoyed at least some grudging respect across sectarian lines. The ensuing decade dulled his sheen somewhat, as his soldiers were implicated in some of the same abuses and sectarian violence as other factions, and his political partisans, the Sadr Movement, proved every bit as susceptible as other parties to the temptations of corruption. In 2008, Sadr officially disbanded his Mahdi Army militia, although much of its structure and membership survived in other guises within the Sadr organization. In 2014, in response to Sistani’s call for fighters to resist the Islamic State, Sadr launched Saraya al-Salam, (“Peace Companies” or “Peace Brigades”), a successor militia to the Mahdi Army which included most of its veteran officers who hadn’t moved on to other, more militant organizations.

Sadr’s trajectory has not been a simple one-way ascent from militia strongman to political player. His story abounds with course-changes and seeming contradictions. For example, he has witheringly attacked the Iraqi political system, even as he has deeply embedded his politicians within it. And though in 2018 he has mounted a new campaign against corruption, throughout the post-invasion years, Sadrists won a hard-earned reputation for epic corruption in their government fiefs, including the lucrative and critical health ministry which they controlled from 2006–07.

Unlikely Partners for Reform

In 2015, the rise of the Islamic State shattered the business-as-usual trajectory of Iraqi politics. Sectarianism had flourished, along with the corrupt spoils system. But foreign influence on Iraqi politics, along with security services crippled by corruption and no-show ghost soldiers, was no match for the Islamic State. Many Iraqis already had reached a breaking point because of raging unemployment and the government’s failure to provide basic services like electricity. Basic services had never been fully restored since the American invasion of 2003, despite years of banner oil profits, mostly lost to corruption. Protest camps sprung up around the country. In Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, followers of Sadr got to know followers of the secular reform parties, including the Communists. Over time, trust grew. Leaders of the secular parties were invited to meet with Sadr.

By the time the Islamic State shattered Iraq’s sense of security, Sadr was already changing course. With the protest movement, he adopted a newly moderate and inclusive rhetoric. Sadr threw his weight behind the protesters. He encouraged his political movement and followers to make common cause with secular reformers and independent technocrats. His followers ceased their very public attacks on homosexuals. “He has undergone a change, an evolution,” said Raid Jahid Fahmi, the secretary general of the Iraqi Communist Party, who has led the secular embrace of the cleric Sadr. “You will find a change in his vocabulary and thinking.”2

“Sadr is ready to cooperate with anyone with Iraqi interests,” said Fahmi. “This was a very important cultural shift.”3

After joining forces with protesters from other factions in 2015, Sadr and his top lieutenants repeatedly met with potential partners. Over time, leaders in the Iraqi Communist Party and the Iraqi Republican Party, led by a secular Sunni pro-American businessman named Saad Janabi, grew convinced they could trust Sadr—and that they would be given an equal role in designing the alliance, even though their parties were much smaller than Sadr’s following.4

“Moqtada al-Sadr is the only person who can summon one million people with a single call,” Janabi said. Secular Iraqis and even some sectarian Sunnis have come to believe Sadr’s nationalist rhetoric, he added.5

In coalition with his new partners, Sadr said he would support an entirely new group of technocratic candidates under a new name. He disbanded his existing “Ahrar” parliamentary bloc, with thirty-four members. He ordered them all not to run for reelection, clearing the way for a new slate of technocrats—the vague term of choice for Sadr and his movement to describe the putative category of professional, independent experts who they believe could improve the Iraqi government’s performance, unfettered by sectarian or political allegiances. Sadr’s new party is called “Istiqama,” which means “integrity,” and the overall coalition with the Communists and other smaller members is called “Sa’iroun,” which means “On the move,” or “Marching,” with the intention of evoking a march toward reform. The alliance’s goals are clear: a civil, secular state, run by technocratic experts who can fight corruption and improve governance.

Sadr’s New Platform in Context

Sadr’s record makes his positioning today all the more interesting. In the pivotal 2018 parliamentary elections, he has declared himself the leading opposition reform candidate. Some of his new claims strain credulity because of his checkered record, but his sheer power and loyal following mean he always has potential as a kingmaker. Electoral math makes unlikely his ambitions of winning the prime minister’s job for his political movement, but he is establishing an entirely new style of politics and rhetoric, which holds critical promise for Iraq and possibly for the entire region.6 First, he has fashioned a potentially inclusive national narrative from the grisly history of sectarian violence that has buffeted Iraq since 2003. Second, he has deftly eclipsed paralyzing political binaries, by forming an alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party and a small array of independent, secular reformists. Third, he has spurred an open discussion of the central problem of Iraqi politics: the “muhasasa” system, most accurately rendered as the “allotment” or “spoils” system.

“This alliance is something new,” said Fahmi, the Communist leader, who has led the secular embrace of Sadr.7 “The political process must shift to a citizenship state from a constituency state. The sectarian quota system is incapable of giving solutions to the problems of the country.”

Since the fall of Saddam’s dictatorships, elections have done nothing to dent the sectarian-based patronage structure in which there is no opposition to the government, but only a shifting free-for-all to feed at the public trough. Elections merely determine what share of power each party gets—the more votes a party secures, the more profitable the ministries to which it lays claim. No successful party has ever refused to take part in the government, joining in the broken-piñata frenzy of corruption that has characterized Iraqi governance at least since Saddam’s era.

The 2018 elections come at a moment when much has changed in Iraqi politics, and Sadr has carefully shaped his movement to make the most of it. The upcoming vote arrives on the heels of a successful military campaign against the Islamic State (in which Sadr’s fighters played an important role), and the coming of age of Iraq’s Shia sectarian militias and Islamist parties. The Shia Islamist militant parties have dominated Iraq since 2003. They have defeated their main external rivals and corralled Kurdish separatism. They have fought each other, sometimes in bitter political contests and at times in outright war, as in 2008 when Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki drove Sadr’s Mahdi Army out of Basra. Today, being a Shia Islamist militia no longer serves as a politically distinguishing identity. All the major electoral coalitions are led by Shia politicians, and most include some Sunni and Kurdish partners and candidates. Fissures within the Shia political space have strengthened other layers of political identity. Politicians now distinguish themselves by their approach to securing Iraq in the future from a resurgence of the Islamic State; balancing the influence of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United States; and solving the nagging problems of poverty, development and corruption. While other Shia political parties are experimenting with nationalist identity in the wake of the campaign against the Islamic State, Sadr has been identifying as a nationalist for years. He stands out further still by his vigorous support for the idea of a civil, even secular, state.

Security officials still worry about continuing threats from the Islamic State, but according to some Iraqi analysts voters have already moved on. Polling, they say, shows that Iraqis are more concerned about livelihoods than anything else. “Security is no longer a priority,” said Sajad Jiyad, head of the Bayan Center, a think tank in Baghdad.8 “They’re asking for jobs, not for security.”

Yet even as Iraqi politicians pivot to face these new voter priorities, the electorate is meeting them with increasing suspicion and cynicism. Sadr has presented himself as something of a political outsider—and certainly not one of the Baghdad elite. His reinvention as a coalition builder enhances his appeal, suggesting he means it when he says he is ready to do business in a new way.

“The state is failing,” said Dhiaa al-Asadi, leader of the current Sadrist bloc in parliament and a political operative very close to Sadr.9 “The existing political elite are part of the problem. They can’t be part of the solution.”

Sadr wants to see the militias formed to fight the Islamic State fully reintegrated into Iraqi government control. He wants sectarian quotas abolished for public sector jobs and government positions. He wants a carefully balanced foreign policy that keeps Iraq equidistant from Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United States. He has also been one of the only important Iraqi Shia leaders to oppose the involvement of Iraqi Shia militias in the Syrian civil war.10 He wants to come to terms with separatist Kurds. Above all, he wants to jumpstart the moribund economy to provide jobs and salaries to Iraqis—the poorest of whom are disproportionately part of Sadr’s following.

In this context, Sadr’s frontal challenge to the central narratives of Iraqi governance since 2003 has the potential to force the ruling parties to shift their rhetoric and approach. Indeed, the process can already be seen in action.

Bridging Old Rifts

Take, for example, Sadr’s changing relationship with Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who, despite reservations about Sadr that have at times erupted into violent confrontation, has continued to court and collaborate with the cleric. Abadi has gone so far as to adopt some of Sadr’s rhetoric. One billboard at the entrance to Baghdad shows Abadi’s face and reads, “corruption and terrorism have one face,” echoing the Sadrist protest slogan, “corruption is terrorism.”

Abadi’s wary embrace of Sadr is especially significant given that the many of the latter’s supporters view Abadi as a villain. One recent demonstration, in February, marked the one-year anniversary of the death of fourteen demonstrators—killed at the hands of Abadi’s security forces while marching toward the Green Zone. Marchers carried flag-draped coffins commemorating the “martyrs for reform” in the same manner that they would honor martyrs who died fighting the Islamic State.

Abadi and his allies have opted to accept Sadr as a potential partner, although Sadr’s critical rhetoric has made them wary. “I think we should distinguish between the election campaign and the reality,” said Sadiq al-Rikabi, a member of parliament and a close ally of the prime minister.11 “It is very easy to stand against corruption,” he added, but much harder to articulate tangible policy proposals.

Perhaps even more significant than Sadr’s partial rapprochement with Abadi is that with Sistani. Despite Sadr’s persistent popularity, Sistani’s influence remains more important—but also more diffuse. Sistani’s clout with Iraqi Shia is not absolute nor instrumental; he doesn’t directly control any political parties or militias, and despite his extensive efforts, he has been unable to persuade Shia politicians to avoid corruption, violence and sectarianism. Still, his edicts hold force. It was a fatwa from Sistani in 2014 that created the popular mobilization units (“al-hashd al-sha’abi,” or PMUs). Almost all Shia in Iraq heed Sistani’s edicts, and he has been credited on multiple occasions with limiting the deleterious impact of Iraq’s worst crises. Sistani has telegraphed his disappointment with the record of the Shia Islamist parties that have dominated Iraq’s government since the 2005 elections. The Shia parties almost uniformly try to claim the approval of Sistani and the other senior Shia clerics, even when Sistani has made clear that he supports none of them. Sistani warned leaders of the Shia militias not to parlay their battlefield success into political campaigns, but most of them ignored the order, to Sistani’s chagrin.

In an interview, a representative of Sistani criticized militia leaders for seeking “political advantage” from the “blood sacrifice” that Iraqis of all sects made in the resistance against the Islamic State.12 As the parliamentary campaign has heated up, Sistani has made his displeasure even more clear. One cleric close to Sistani went on Furat Television to warn voters not to make their choice based on sect.13 “The corrupt people we have voted for have robbed the nation. We ought to not vote for them again, even if they are members of our clan or sect,” said the cleric, Rashid al-Husseini.14 “I would rather trust a faithful Christian than a corrupt Shia.”

Historically, Sadr has been at odds with Sistani and the other senior clerics in the marjaiya. In the current campaign, however, he has closely shadowed Sistani’s pronouncements about corruption and the need to elect new leaders. In recent statements, Sadr has addressed skeptical voters who have lost faith in the political process because of the corruption and failures of previous Iraqi governments, including those with the participation of Sadrists. “We will not be deceived by the lies again,” Sadr wrote in an April 14, 2018 statement.15 His own movement’s previous failures, he said, “give the motivation and determination to succeed in this election.”

On April 4, 2018, Sadr released a series of arguments against boycotting the elections. “Some ask, and say: the corrupt and the old faces will stay in power whether we vote or not,” Sadr wrote. He offered thirteen rebuttals, evoking religious loyalty, patriotism, optimism, and the responsibility of citizenship.16

In today’s Iraq, Sadr boasts a unique status.17 He can count on nearly absolute devotion from his rank-and-file followers, his organization, his political party and his militia. Even Sadr’s opponents recognize his political heft. In this, he is different from other Iraqi religious leaders only in degree: Mowaffak al-Rubaie, a former national security adviser who is close to several senior Iraqi politicians, said that millions of Iraqis venerate clerics and will do whatever those clerics instruct.18 During a visit by Sadr to the Kadhamiya shrine in Baghdad, Rubaie recalled, Sadr’s followers crowded the cleric’s jeep to touch the dirt on its wheels, which they smeared on their heads as a blessing. “If he orders these people to set themselves on fire, they will do it,” he said.

Sadr’s positions have appealed to Iraqis who are weary of conflict but seek to maintain dignity and integrity in their foreign relations. For example, Sadr has softened his rhetoric about secularists, and has been willing to mend fences with Saudi Arabia and criticize Iran. But at the same time, he has maintained a hard line against the United States, whose influence in Iraq he considers wholly malign.

The fact that those positions are accommodating while remaining tough and without being overly compromising—much like his evolving relationships with Abadi and Sistani—make his calls for unity that more meaningful.

“Healing is gradual,” he said in the April 14 statement. Iraq has never before experimented with professional technocratic politicians, “without any partisan or religious or ideological or ethnical indications, to choose the most effective and the best [leaders] for the love of Iraq, and the love of Iraq is of faith.”

Managing Expectations

If this account of Sadr’s well-timed transformation into a champion of nonsectarian political reform sounds a little too gung ho, there are plenty of structural and historical reasons to readjust expectations to a more realistic level.

The results of the May 12 election are likely to set in motion a long negotiation process; many seasoned Iraqi politicians and analysts believe the outcome will be another unity government like all those that have ruled Iraq since the U.S. occupation, with goodies and power divided among sectarian parties. Sadr has pulled many about-faces before; he may tire of the alliance with secular parties, or he might decide he can better serve his constituents by joining yet another weak coalition government. “Moqtada al-Sadr has been on television and in politics for fifteen years and he has accomplished none of his goals,” said one political insider close to the government. “He has been revealed to be someone who cannot be trusted.”19

Fighting Sectarianism

Specific aspects of Sadr’s past raise questions about his sincerity. For example, despite his maverick image, he has played his part in the problem of sectarianism. The Mahdi Army orchestrated some of the worst ethnic cleansing and sectarian killings of 2006, although Sadr subsequently pulled his loyalists back. Many of his extremist supporters defected to other organizations or founded their own, like Qais al-Khazali, who is now the leader of Asaib al-Haq, a Shia militia close to Iran.

Some secular leaders never overcame their mistrust of Sadr, with his religious background and history of secrecy and political about-faces. One of the secular reform leaders who rejected the coalition is Shirouk al-Abayachi, leader of the National Civil Movement and a member of parliament.20 Sadr’s organization is “foggy” and evasive, she said. “One year ago they would call us infidels,” she said. “We don’t know what they want from us.” If the Sadrist alliance does well in elections, she said, history suggests that Sadr and his lieutenants will make the important decisions, rather than deferring to the independent secularists from tiny parties. “We don’t just want seats in parliament,” Abayachi said. “We want to build a clean alternative.”

Despite his conciliatory reform rhetoric, Sadr has been willing to turn to outright confrontation with the state. Despite his status as a junior partner in the Iraqi government, Sadr personally broke through the security cordonsurrounding Baghdad’s Green Zone in March 2016.21 His followers set up a protest camp in the heart of the government, even briefly occupying parliament and the prime minister’s office.

Pervasive Corruption

When it comes to fighting corruption, there are similar reasons to moderate enthusiasm for Sadr.

Existing anti-corruption efforts suggest it will be difficult to make meaningful inroads against the spoils system. “The system needs to be reformed but there is no incentive to reform,” said Ali al-Mawlawi, director of research at the Baghdad think tank the Bayan Center.22 “The government has hard evidence, but the corrupt judiciary won’t prosecute.”

Even Sadr’s own politicians have struggled to have an impact, and critics of Sadr’s reform program point out that it is short on specifics. Jumaa Diwan al-Badali is a Sadrist member of parliament who represents the poor Baghdad district of Sadr City (which takes its name from Moqtada al-Sadr’s father, Mohammad al-Sadr); Badali is also the rapporteur of parliament’s integrity committee, in charge of investigating corruption. His experience shows the limits of any serious effort at reform. His committee has publicized some problematic contracts, often resorting to media leaks to force the government to pay attention. Parliamentarians have uncovered kickbacks and fishy contracts in the department of defense, including one case, Badali said, where the department attempted to buy subpar and nonexistent equipment for the fight against the Islamic State.23

The biggest contract they stopped was a $2.5 billion weapons deal with China, which was part of the 2017 budget. Badali believes the U.S. encourages corruption in Iraq as a way of keeping the country and its security forces weak. “I don’t accept the prime minister’s depiction of Iraq as a pool of corruption,” he said. “We are a country with some corruption. We are not the most corrupt country in the world.”

Aside from the general difficulty of rooting out corruption, Sadr and his allies are hardly innocent of graft themselves. Sadr’s militia, the Saraya Salam (“Peace Brigades”), a PMU created in 2014 from the remnants of the Mahdi Army, has benefited from government funding. Corruption clearly played a role in eroding the combat readiness of Iraq’s security forces prior to the rise of the Islamic State, but the rise of new security institutions, including the PMUs, has only fueled the type of corrupt militia patronage that has hobbled the central government.

Over the years since 2003, Sadrist ministers and members of parliament joined the corruption frenzy as well, taking kickbacks and doling out patronage jobs through ministries under their control. Sadr’s principal secular ally, the Iraqi Communist Party, also enjoyed influence through the spoils system, winning positions in the cabinet despite very winning very few votes. Fahmi, the current Communist leader, served as minister of science and technology from 2006 to 2010. Fahmi preserved his reputation for probity through his time in government, although—critics of the Sadrist reform project are quick to point out—he wasn’t able to roll back corruption by other parties in government.

“Who can fight corruption?” said Ahmed al-Krayem, a tribal leader and provincial politician who alleges that Sadr’s followers and fighters participate in the same kickbacks and extortion schemes as every other Iraqi political party and militia group.24 “The Sadrists won’t fight corruption.” Even the prime minister, Krayem pointed out, has been dogged by allegations of corruption from his earlier stints in government before taking over as premier.

Interestingly, Sadr doesn’t refute charges that his own movement is implicated in the failures of past attempts to root out corruption, but rather insists that change depends on continuing engagement and changing tactics. “We didn’t hope to be corrupted,” he wrote in answer to one supplicant who asked how Sadr justifies his political campaign given that his movement has participated in every single one of the corrupt governments since 2003. “We are rising up against the political process from the inside, rather than from the outside.”

Profound Political Problems

Some of the differences within the Sa’iroun coalition seem unbridgeable. Sadr’s Shia followers fought the United States and died in droves. Janabi’s secular followers include many elite Sunnis who are openly fond of the Americans. The Communists, meanwhile, have a long history of tensions with the clergy. Still, supporters of the alliance say these differences won’t lead to political fissures. “Sadr can control his people if there are problems. We will control our followers,” Janabi said. “We agree about fighting sectarianism.”

Another sticking point for Sadr’s agenda may be that the idea of apolitical “technocrats” who just get the job done may be something of a fantasy—at least for Iraq.

Even Sadr’s supporters point out that technocrats can only have impact if they are effective politicians. “I don’t believe in technocrats,” said Hakim al-Zamili, an influential Sadr lieutenant who runs the parliament’s security committee.25“Only a strong politician with a base in a political party can succeed. The country is full of militias, people with weapons in the streets. An independent technocrat without a political party can’t do anything.”

Independents have served as ministers in Iraq since 2003, and none has managed to change the system. The types of figures who can change the system, Zamili said, are tough political veterans with the backing of formidable parties. “Maybe a political technocrat like me can do something,” he said. “No one can threaten me, no militia. I can speak, I can interrupt someone, no one can stop me.”

Iraq’s system is broken; it might benefit from repairs, but Iraqi voters should not expect a wholesale revolution. “Let’s be honest—we can’t accomplish everything we are planning,” Zamili acknowledged.

Murder in Samarra

Power politics in Iraq can play out at a visceral level, and one recent incident has underlined both the frailty of Sadr’s new vision, and its promise.

Sadr has repeatedly taken the position that there should be only one central authority in Iraq—the state—and that all militias must be integrated into government control. At the same time, he commands thousands of militia fighters in the Saraya Salam, most of them stationed in the flashpoint shrine city of Samarra, north of Baghdad. Samarra is a mostly Sunni city that is home to one of the most holy spots for Shia Muslims, the site where it is believed that the twelfth imam went into occultation in the ninth century. Sunni extremists blew up the Shia shrine in Samarra in February 2006, setting off one of the deadliest periods of sectarian fighting in Iraq. Islamic State fighters held sway in Samarra until Shia militias drove them out in 2014.

Since 2015, Sadr’s militia has held sole control of the city. According to Sadrists and Saraya Salam commanders and fighters, their tenure in the city has been a model of success. They have formed partnerships with local business owners and tribal leaders, most of them Sunni, and have restored security and the business that comes with pilgrimage traffic. Critics accuse the Sadrists of ruling the city with an iron fist, detaining political critics, and extorting money from local traders and business owners. The accusations were repeated in multiple interviews with the author, and aren’t out of the ordinary in Iraq; in fact, the accusations levied against the Sadrist militia are much milder than those heard in zones ruled by other Shia militias, where displaced Sunnis live in fear of disappearance and, in some places, of summary execution.

The fact remains that the Sadrists are running a fiefdom, a state-within-a-state in Samarra; while such behavior is the norm in today’s fragmented Iraq, it contradicts the Sadrist platform of reforming the state under a unified nationalist banner. In March, the dangerous equilibrium resulting from so many overlapping security forces collapsed with a shootout between allies in Samarra. On Tuesday, March 13, the prime minister’s personal security detail was driving north in a convoy, preparing for Abadi’s planned visit later in the week to Mosul. The road took them through Samarra. At the town’s main checkpoint, according to two members of a committee that investigated the incident, the convoy refused to stop at the Saraya Salam checkpoint, as they are required to by law.26 Commandos from Battalion 57 of the Iraqi Army, the prime minister’s special unit, went so far as to confiscate weapons from some of the Saraya Salam fighters at the checkpoint. “It was humiliating,” said one of the members of the investigative committee that visited Samarra days later.27The angry fighters radioed ahead to the next checkpoint, a kilometer away, where Saraya Salam militiamen blocked the road with Humvees and confronted the convoy. Dozens of gleaming black sports utility vehicles swarmed the checkpoint. The army unit then fired toward the checkpoint. The Sadrists returned fire, killing Brigadier Sherif Ismail, the battalion commander and a trusted supporter of the prime minister.

Both Sadr and Prime Minister Abadi avoided public recriminations, and ultimately the killing was settled through a tribal agreement. The military unit, according to the investigative committee, was at fault for ignoring proper checkpoint procedures. “We need to develop a culture of respect,” said Zamili, the Sadr lieutenant, who was one of four members of the investigative committee. Another member of the investigative committee, who is not from either the prime minister’s or from Sadr’s bloc, blamed a lack of professionalism. “They were arrogant. They wanted to show off, they didn’t want to follow the rules,” the member said. “It was 100 percent an accident.” Political, military and economic power are inextricably intertwined, and state authority is severely compromised. This particular killing strained but did not break the alliance between Abadi and Sadr, but it revealed yet another potential point of rupture. Tellingly, it was resolved not by the judicial system or by a formal political process, but by a combination of ad hoc investigation and informal tribal justice.

Turning Point Election

The 2018 elections will set the course for Iraq’s government for at least another four years. If the current spoils system continues, with every major party joining into yet another ineffective unity government, Iraq can expect to repeat similar crises. It will be nearly impossible to maintain the effective national security approach that defeated the Islamic State—an approach that required unified command, mass mobilization, and help from all of Iraq’s competing allies, including Iran and the United States. Economic development will require warm relations with Iran, the United States and Saudi Arabia, and, at the very least, a curtailing of rampant corruption. None of these improvements will come to pass without a powerful prime minister, a meaningful opposition, and competent ministers. Sadr’s trailblazing coalition marks a crucial possibility for Iraq: the mainstreaming of civic-secular nationalism, and the passing of national politics from sectarianism into a new phase. More emphatically than any other leader, Sadr has abandoned religious and sectarian discourse, showing that a Shia cleric with a sectarian base can embrace civic, secular politics. There is, of course, ample precedent for such politics in the last century of Arab political history, but sadly, very little among contemporary Iraqi political leaders.

An informal quota system reserves the most important job, prime minister, for a Shia, and the presidency and speaker of parliament for a Kurd and Sunni Arab respectively. If this new tradition survives another electoral cycle, it will fast become the kind of pernicious unwritten tradition that cannot be changed—like Lebanon’s sectarian quotas, which have become unassailable even though they are not in the constitution.

In his alliance with Communists and secularists, Sadr has mainstreamed civic politics. If he sticks with his current course, he can also set an example for other leaders who are willing to move past their origins as sectarians, clerics, or militia leaders. Despite his pointed anti-Americanism and history of armed resistance, the United States should welcome Sadr’s new role. So should Iran, which hoped to make Sadr into one of its proteges before the cleric broke with Tehran as well. Sadr’s broadsides against the United States (his lieutenants regularly brand the Baghdad embassy as a “devil” spreading sedition and strife in Iraq) shouldn’t obscure the common interests he shares with the United States and its Iraqi partners: building a strong, effective government and encouraging a nonsectarian, inclusive national identity that can help end the cycle of sectarian violence.

Sadr’s new rhetoric, and his secular political alliance, mark one of the most promising developments in contemporary Iraqi politics. There are plenty of reasons to question his sincerity, or the durability of the partnerships he has forged since 2015, but those partnerships hold the potential to change the tenor of the entire political playing field. Sadr’s reinvention of himself from militant cleric to nationalist anti-sectarian statesman comes at a time when other sectarian movements have begun to realize that they will need support from multiple constituencies in order to survive politically. In the likely event that the alliance doesn’t win enough seats to form a government, it can contribute still more profoundly to Iraq’s political development by opting to stay out of power and serve as a parliamentary opposition. Iraq stands at a turning point, where its largely sectarian political movements are experimenting with nonsectarian politics, and where its ruling class is confronting the dead-end to which the spoils system has brought the country. Sadr’s gambit stands a chance, albeit a slim one, of catalyzing the political transformation that Iraq so sorely needs.

To be sure, Iraq will still play host to endemic corruption and patronage, but a sharp change in politics can expand the government’s agenda to include long-term governance along with the usual business of padding state contracts and doling out ghost jobs. Without the sort of transformative nationalist, professional, and anti-corruption politics advocated by Sadr, Iraq is sure to face an ongoing cycle of crises that will destabilize not only Iraq, but also its neighbors and U.S. interests in the Middle East.

One Less Danger but No New Hope as Lebanon Finally Elects a President

Aoun sits at Baabda on election day. Source: OTV screen grab

[Commentary for The Century Foundation.]

Michel Aoun’s ascendance to the presidency of Lebanon on Monday three decades after he first sought the office represents not a sea-change in regional power dynamics but an incremental step in the hard slog of making politics. Nearly two and a half years after the previous president left Baabda Palace and after forty-five failed parliamentary sessions to select a new leader, a thorny dispute with many players was peacefully negotiated. Remarkably, the maneuvers unfolded peacefully despite the pressure caused by a state collapse next door in Syria and with considerable threat of violence hanging over Lebanon itself.

The outcome of the Lebanese presidential selection has been oversold in some quarters as a big victory for Iran in its regional struggle against Saudi Arabia. The truth is more prosaic, complicated, and local.

None of the major political factions can justly be considered to have won outright, and the mind-numbing turns of the deal make clear that there aren’t any simplistic sides in Lebanon (or for that matter, in political life throughout the Arab region).

Political alliances in Lebanon—like in the rest of the region and the world—are in fact fluid and partial, by turn ideological and transactional.The anticlimactic election and the ongoing limping politics that are sure to follow make clear that no simple equation can reduce Arab politics to glib but ultimately misleading formulations, like those who lump together Shia, the Iraqi government, Hezbollah, Iran, and one Lebanese Christian faction into a single monolithic construct. Nor were Aoun’s opponents a unified bloc connecting Sunnis, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Syria’s opposition.

In short, the messy deal for Lebanon’s presidency, while hardly a triumph for any single idea or movement, provides a sharp reminder that politics and negotiation continue to play a key role in forging paths forward in a region where violent contestation of power usually grabs most of the attention.

All Politics Is Local—and International

The decision of Lebanon’s parliament to bless the Aoun deal says as much about the evolution of Lebanon’s model of power-sharing-cum-paralysis as it does about the region’s increasingly interwoven struggle for influence. On Monday, the Lebanese parliament—itself an arguably illegal body because it extended its own mandate—ratified a backroom deal to make Aoun president and down the road, to give the prime minister’s job to his rival, Saad Hariri.

This same deal was floated in 2014 after the previous president’s term expired. Back then, supporters of Hariri believed that Sunni rebels might win the Syrian civil war and that political tide in the region would shift, empowering them to sweep to power rather than accept the middling share of it they already possessed. Hezbollah and its allies, meanwhile, were content to muddle forward without a president at all, since they held the position of primus inter pares among Lebanon’s factions and stood to gain nothing important from a functioning executive branch.

After twenty-five months, only the expectations of the major players have changed. Hezbollah is willing to accept a president who, after all, was its candidate, if only to escape domestic blame for leaving the state in limbo. And the weakened party of Saad Hariri, facing fragmentation among its Sunni base and fading confidence from its Saudi sponsors and financial backers, has grown desperate. Hence it was willing to accept any terms to put its man back in the premiership, without any accompanying concessions that would boost its electoral chances later on or award it a bigger share of public sector spoils to loot.

Much went into the Aoun deal, most of it concerning Lebanese internal dynamics. Longtime rival Christian warlords Aoun and Samir Geagea made peace with each other earlier this year, realizing that the country’s Christian minority was losing even more relevance if it remained split between pro-Sunni and pro-Shia factions. Hariri struggled to maintain his position as his family company went bankrupt and Saudi Arabia, briefly but flamboyantly, hung him out to dry—canceling a grant to Lebanon’s military and standing by as its man in Lebanon, Hariri, was humiliated in municipal elections this spring.

In the view of his Saudi sponsors, Hariri had not done enough to stop Hezbollah and Iran from dominating Lebanon, so he deserved a comeuppance; that, according to Saudi watchers in Lebanon, was the message the Saudi royal family wanted to send this past year. But they realized that theatrical shows of pique do not wise policy make, and that by cutting off Hariri they made it easier for Hezbollah and Iran to conduct their political business in Lebanon. In the end, Lebanon mattered to the Saudis more than they initially thought.

It also ultimately turned out that Lebanon had some say over its own choice of leader. Aoun is not a president built and chosen by foreign powers, or at least not 100 percent so (his followers like to say that “the General” is 100 percent “made in Lebanon,” which exaggerates the point in the other direction).

Aoun formed a tight political partnership with Hezbollah in 2006, a surprising move at the time for a leading Christian warlord who had made his reputation by going to war against Hezbollah’s patron Syria in 1989.

But Aoun is not purely Hezbollah’s man, which is one reason why Hezbollah was willing to wait so long to help him get elected by parliament.

The General is considered unpredictable, headstrong, vain, ambitious, and a bit mad. Those are the characteristics which lead his most ardent admirers to see him as a charismatic leader and his enemies to fear him as unpredictable and prone to authoritarianism.In office, he will polarize and hector. Already in his inaugural speech on Monday he made chauvinistic, unfulfillable promises to try to send some of the 1.5 million-plus Syrian refugees in the country back home. He vowed to defend his nation against terrorists and Israel, to strengthen the military, and a cleaner government. But he will be hemmed in by Lebanon’s dysfunctional political power-sharing system, which his election does nothing to change.

Low Expectations

Given the tradition of painstaking and painful political negotiation in Lebanon, it might take a year, even two, for Saad Hariri to form a government and take office as prime minister. By then, new parliamentary elections will be underway. No one in Lebanon expects the state to function like a state any more than it has during the last five years of permanent crisis during which electricity, education, and health care have been in scarce supply, but graft and uncollected garbage have risen to historically high levels.

Events in Lebanon are not solely a byproduct of regional competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Nor can they be read simply as a fight between Shia Hezbollah and the Sunni Future Movement.

It is instructive to remember that initially, two sectarian Muslim factions, the Sunni Future Movement and Shia Hezbollah, were negotiating over the outcome of the most senior post in Lebanon still reserved for Christians; in Lebanon’s sectarian political game, the Christians had largely sidelined themselves from their own remaining political fiefs. Eventually, intra-Christian competition made a greater number of Lebanese warlords relevant: not exactly a step toward democracy, but new alliances between Christians kept an oligarchy from sliding into a duopoly. Those who describe Aoun’s victory as a win for Iran should reckon honestly with the fact that the alternative candidate backed by Saudi Arabia was Suleiman Frangieh, a Christian warlord whose fealty to Damascus, Hezbollah and Iran is far more ironclad than Aoun’s.

In a region where the local, regional, and international all interact, Lebanon’s presidential crisis embodied all three levels, and its resolution offers one image of how plodding, incremental, and frustrating it is to seek progress on any level at all.

On Monday, Lebanon moved one step away from the abyss of total paralysis. It is, however, hardly any closer to restoring a state that can manage anything remotely resembling governance.

It might not seem like much, but the Lebanese system has managed one feat that can allow its citizens, however modestly, to maintain their claim to provide a model for regional politics: against considerable odds and obstacles, many of their own making, Lebanon’s politicians have pursued political compromise by nonviolent means. That’s no small feat.

Here & Now Egypt Elections Preview

Robin Young at WBUR’s Here & Now talked with me today about the possible outcomes in Egypt and their implications. All predictions are useless at this point; looking forward to seeing the voting tomorrow, and the results next week. Listen here.

UPDATE

Some additional radio appearances about the voting in Egypt. KCRW’s To the Point had Jehan Reda, David Kirkpatrick, Shadi Hamid, Dan Kurtzer and me on yesterday. Listen here. And KUOW talked to Borzou Daragahi and me earlier; listen here.

A Primer on the Arab World’s First Free Presidential Election

A volunteer for Egyptian presidential candidate Amr Moussa folds t-shirts. (Reuters)

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

CAIRO, Egypt — What should we look for after the votes are counted in Egypt this week — or rather, if the ballot box contents are counted, rather than trashed or illicitly augmented?

Once Egyptians go to the polls on Wednesday to choose a president, no matter what happens next, the transition from impermeable autocracy to something hopefully more accountable will move to another, more clarifying, stage.

The integrity of the process will be the first hurdle. And if Egyptian monitors and political parties endorse the count and the turnout is significant, as expected, the results will be the second.

Because opinion polling in Egypt has not yet had a semblance of accuracy and since there is no precedent for a contested presidential election in Egypt, there are simply no meaningful metrics to handicap the race. Many Egypt watchers have picked likely front-runners, but this is nothing more than educated guesswork. My own prediction is that the top three finishers are likely to be Amr Mousa, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh and Mohamed Morsy, and that whichever of the two Islamists makes it to the runoff will win.

But this is little more than high-level gut-work, based on a reading of the parliamentary election results earlier this year, Egypt’s only real election since 1952; an assessment of public opinion and emerging political thought; haphazard street interviews; and the size and quality of crowds at electoral rallies.

The electorate is fragmented, with at least five candidates have attracted significant followings. As a result, that many or more could poll in the double digits. The field is wide open, especially because of the fluid nature of political allegiances in this period of transition. The major constituencies will be split among rival candidates from the same camp: Islamists, revolutionaries, law-and-order nationalists, liberals.

Men sitting at a café during the four-and-half-hour presidential debate a week ago told me they supported both the Muslim Brotherhood and leading secular candidate, Amr Moussa, who is presenting himself as a sort of elder statesman. Some told me they were attracted simultaneously to Hamdeen Sabahi, the secular Nasserist revolutionary favorite, as well as Ahmed Shafiq, the revanchist retired general and Mubarak’s last prime minister. That’s a sign of emerging politics, as voters begin the complex process of ranking their own preferences. How important is a candidate’s connection to the old regime? Position on law-and-order versus reform? Stringency on clerical regulation of civil law? Strategy on reviving Egypt’s moribund economy?

None of the choices are clear-cut, and none of the popular candidates has an uncomplicated constellation of views. For instance, the most Islamist candidate, the Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, is more rigid in his religious views and less sophisticated in his economic ideas than other senior Brotherhood leaders. And the only secular candidate who supported the Tahrir Revolution from the beginning, Hamdeen Sabahi, is also an unreconstructed Nasserist, which is a bit like campaigning in America today as a third-party reformer who wants to bring back Communism.

The top two finishers will go to runoff, to be held on June 16 and 17, which will determine Egypt’s president. Here are a few of the possible outcomes and their likely implications.

Felool runoff: Moussa vs Shafiq. This is the worst of the plausible scenarios, but it’s possible. Thefelool, or “remnants” (meaning leftovers from the old, Hosni Mubarak regime), could prevail. Amr Moussa, the former foreign minister, could finish atop the polls with Ahmed Shafiq, the ex-general who, during his campaign, promised that he would never let a minority group of protesters overthrow a president backed by millions. Never mind that Mubarak said the same thing in his final weeks in power. In this case, Islamist voters and secular revolutionaries would both be likely to take to the streets, convinced that all the political achievements of the Tahrir uprising were under threat. We could expect a tense power struggle with lots of public uproar, and potentially even more uncertainty and violence than we’ve seen over the last year.

Islamist runoff: Morsi vs Aboul Fotouh. The Brotherhood’s Morsi could finish at the top along with the former Brother, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. In this case, we could expect a surge of conditional popular support for Aboul Fotouh, the more conciliatory and moderate of the two — but we should also expect the military, some of the wealthy magnates, and the anti-Islamist secular constituency to bristle and polarize. The non-Islamist politicians might pursue obstructionist tactics, in the belief that their secular principles are under attack.

Glass half full. In this scenario, the runoff features what I call “consensus” candidates, liked by some and acceptable to many, even with reservations. These candidates elicit intense dislike from a minority of Egyptians, but a majority would be willing to live with them. On this list, I’d include Aboul Fotouh, Moussa, and Sabahi. Of the likely outcomes, this is the best; it means that the new president would be unlikely to face a public insurrection, and that he would be able to govern with at least the grudging consent of the majority during the next phase of Egypt’s transition.

Wild card. Given the unpredictability of the process and the split vote, the finalists could include one or two unexpected faces. The revolutionary Sabahi could face Amr Moussa, disenchanting those revolutionaries with an Islamist hue. The reactionary ex-regime Shafiq could face the reactionary Islamist Morsi, leaving a huge swathe of the electorate without a simpatico candidate. The ruling generals could mistrust both finalists and organize a more concerted power grab.

Whichever two candidates make it to the run-off, the very fact that a genuine presidential contest is taking place has irreversible historic implications. Egypt is writing a new political history for itself, an inevitably messy process. Any outcome (short of a Shafiq victory) will likely represent a marked improvement from political life under Mubarak. And whatever the results, the politicization of the electorate will continue, and the public is unlikely to forfeit its newfound sense of ownership over the government.

Inside the Three-Way Race for Egypt’s Presidency

Leading Egyptian presidential candidates Amr Moussa, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, and Mohamed Morsi. / Reuters, AP

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

CAIRO — Egypt’s first real presidential contest ever, for which the candidates met last night for the Arab world’s first-ever real presidential debate, has all the makings of a genuinely interesting fight. The front-runners nicely capture a wide stretch of the spectrum, while leaving out the extremes. Voter interest appears high, and the military rulers seem unlikely to allow major fraud based on their record with parliamentary elections.

But enthusiasm about the debate should not obscure the unsatisfying circumstances of the presidential election, which itself does not guarantee a full transition to civilian rule or democracy.

The president’s powers still have not been delineated, and the significance of the race and its victor could be heavily tarnished by future decisions about the assembly that will write the next constitution, among other unresolved questions about whether Egypt will have a presidential, parliamentary, or hybrid system.

Islamists have proven themselves to be the dominant political bloc, garnering more than two-thirds of the vote in parliamentary elections earlier this year. The winner of the presidential race, even if he is secular, will owe his victory to Islamist voters, and will have to govern in tandem with a parliament that has a veto-proof Islamist majority. Islamist politics are malleable and by no means monolithic, but they will drive the political agenda after decades of total exclusion.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF, has heavily manipulated the process, deepening its unaccountable and authoritarian mechanisms of control. Crony-packed courts and the presidential election commission have made a series of arbitrary decisions. Egypt’s next government will have to negotiate artfully to wrest the most important powers out of the hands of generals.

The campaign has galvanized Egyptians. This week, the candidates crisscrossed the countryside in bus caravans, and thousands turned out in even the minutest villages.

“He has a special charisma,” gushed an English teacher named Ahmed Abdel Lahib, during a pit stop by the Amr Moussa campaign in a Nile Delta hamlet called Mit Fares. “Egypt needs a man like him,” he said of the former Arab League secretary-general.

Hundreds of men thronged the candidate, shouting, “Purify the country!” and “We want to kiss you!” In his tailored suit, and carrying the patrician demeanor he honed over decades as Egypt’s foreign minister and then Arab League chief, Musa clambered onto a makeshift stage for his short stump speech (fix agriculture, the economy, and health care, long live Egypt!). Men pushed over chairs and slammed one another into the walls of the narrow alley to get closer to Moussa and touch his sleeve.

The oaths of loyalty felt a tad staged and excessive, but similar displays characterized all the major candidate rallies, and could reflect the old authoritarian rallies, or a desire for a galvanizing leader like Gamal Abdel Nasser, the nationalist colonel who took power in a 1952 coup, or simply the enthusiasm of voters who for the first time in their lives will likely get to choose their president.

Moussa has presented himself as a secular elder statesman who can stand against what he portrays as a power-hungry Islamist tide, personified by the other two front-runners: the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi and the ex-Muslim Brother Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. It is Aboul Fotouh who most worries Moussa’s strategists: he is giving the former minister a run for first place, marketing himself as potential bridge candidate, a “liberal Islamist” who can appeal to Islamists as well as the secular nationalists and revolutionaries who are wary of Moussa’s connections to the old regime.

Thousands of fans in the market town of Senbelawain waited hours on a recent night for Aboul Fotouh, who seems perpetually delayed by traffic (he was late for the historic presidential debate for the same reason). When he arrived, the retired doctor was greeted like a rock star with swoons and chants. Bearded Salafis and women in full-face-covering niqabs jostled with clean-shaven students.

Aboul Fotouh is a more gripping orator than Moussa, with a gruff, gravelly voice that he controls well, shifting cadence to maintain his audience’s attention. “If this country succeeds, the whole Islamic world succeeds,” Aboul Fotouh shouted, provoking cries of exultation. He talked extensively about sharia, in a way apparently calculated to burnish his Islamist credentials while reassuring his left flank that he opposes such literal interpretations as severing the hands of thieves. Aboul Fotouh’s stump speech played to his Islamist base rather than to his revolutionary and secular sympathizers.

A Muslim Brotherhood member in the audience named Yousef Eid Hamid, 38, said he was campaigning for Aboul Fotouh in defiance of his organization’s strict orders to vote for Morsi. “We are not machines,” he said. “You cannot love a candidate, and then just change.”

Backroom deals with the military will likely be decisive in determining how the winner can govern, but retail politics seem to be taking root for now. During Thursday night’s debate, the two front-runners, Moussa and Aboul Fotouh, dug at each other’s records. Aboul Fotouh portrayed Moussa as a corrupt, weak stooge for Mubarak who will continue the old regime’s authoritarian ways. Moussa attacked Aboul Fotouh as a fire-and-brimstone Islamist who founded a radical group in the 1970s and now disingenuously presents himself as a moderate.

Egyptians crammed cafes to watch. During a half-time walkthrough (the debate lasted more than four hours, from 9:30 p.m. to 2 a.m.) at the Boursa pedestrian arcade behind the Cairo stock exchange, I met several people who had voted for the Muslim Brotherhood for parliament but were leaning toward the anti-Islamist Moussa for president.

“I will give the Muslim Brotherhood domestic policy, but I want to keep them far away from security and foreign policy,” said Abdelrahim Abdullah Abdelrahim, 44, an import-export businessman built like a bouncer. “These Islamists want to march on Al Quds” — Jerusalem — “and wage war. It’s not the time for this.”

He went on to mock the Salafi legislator who tried to sound the call to prayer in parliament, and his Noor Party colleague who tried to claim his nose job bandage was really the scar from a politically motivated assault. “People are more tired than before,” Abdelrahim said as he lost another round of dominoes to a friend.

At the presidential rallies in the Delta, I met numerous voters who were shopping or just checking out the opposition. Leftist revolutionaries, committed to minor candidates guaranteed not to reach the second round, listened to stump speeches to consider whom they’d be willing to hold their noses and vote for in a runoff. Confirmed skeptics came, in case they might change their minds.

Arguments broke out. At the end of one Moussa pit stop in Dikirnis, an older man dismissed the candidate as a “felool,” or remnant of the old regime. Another man pushed him hard in the abdomen: “He is not a felool! Amr Moussa is a great man!” The critic scuttled off to his nephew’s pastry shop, where he continued his invective against Moussa. The nephew, 37-year-old Ahmed Burma, smiled benevolently. “My uncle jumped on the revolutionary bandwagon,” he said. “But I’m supporting Amr Moussa. I run a business with 90 employees. Let’s give this guy a chance to work.”

Still, the polls and predictions are little more than guesswork. Most of the voters live without internet or phones and are beyond the reach of the campaigns’ opinion researchers. Egypt has had only one real election in its modern history: the parliamentary ballot that concluded this January. Twenty-seven million people voted, more than two-thirds of them for Islamist parties.

Even with the Islamist vote split between Aboul Fotouh and the Brotherhood’s Morsi, it’s all but assured that one of them will face Moussa in the runoff June 16 and 17. Morsi might fare better than many analysts seem to think, as the Brotherhood deploys its formidable get-out-the-vote operation, which no other campaign can currently match.

The Islamists in parliament haven’t acquitted themselves well, wasting time on fringe religious debates while the economy sinks, deferring to the army on crucial issues such as military trials for civilians, and alienating almost every major constituency in the country other than their own by trying to impose a constitutional convention packed with Salafist and Brotherhood members.

If turnout is as high as it was for parliament (and it might be higher, since the president has always been the commanding figure in Egypt’s modern political system), Moussa would need to convince more than 6 million people, a full third of those who voted Islamist for parliament, to switch allegiance and vote for him. His advisers believe that’s possible.

They also seem to think that Moussa’s year-long bus tour of rural areas will pay dividends, and that their basic selling point resonates with common voters: a pair of safe, experienced hands for a transition.

Nonetheless, Moussa’s strategy smacks of secular liberal wishful thinking, a common affliction among Egypt’s veteran political class in a year and a half of dynamic change. It might just work out for him, but an equally likely scenario would have the voters that propelled Islamists to parliament eager to give someone with their values more of a chance for success than has been allowed by three months of parliamentary machinations under the shadow of the military.

The Inevitable Rise of Egypt’s Islamists

A veiled woman casts her vote during the second day of the parliamentary run-off elections at a polling station in Cairo. Photo: Reuters

CAIRO, Egypt — Egypt’s liberals have been apoplectic over the early results from the recent elections here. Everybody expected the Islamists to do well and for the liberals to be at a disadvantage. But nobody — perhaps with the exception of the Salafis — expected the outcome to be as lopsided as it has been so far. Exceeding all predictions, Islamists seem to be winning about two-thirds of the vote. Even more surprising, the radical and inexperienced Salafists are winning about a quarter of all votes, while the more staid and conservative Muslim Brotherhood is polling at about 40 percent.

The saga is unfolding against a political backdrop of alarmism. One can almost hear the shrill cries echoing in unison from Cairo bar-hoppers and Washington analysts: “The Islamists are coming!” In short order, they fear, the Islamists will ban alcohol, blow up the sphinx, force burqas on women, and declare war on Israel.

Before we all worry too much, however, and before fundamentalists in Egypt start to crack the champagne (in their case perhaps literally, with crowbars), it’s worth taking a look at what’s really happening with Egypt’s Islamists.

Egypt is still not a democracy, so election results mean only a little; the key players in shaping the country remain the military, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the plutocrats. To a lesser degree, revolutionary youth, liberals, and former ruling party stakeholders will have some input. The new powers-that-be in Egypt and other Arab states who are trying to break the shackles of autocracy are likely to be more religious, socially conservative, and unfriendly to the rhetoric of the United States and Israel. That doesn’t mean they’ll be warmongers, or that they’ll refuse to work with Washington, or even Jerusalem, on areas of common interest.

Islamism has been on the rise throughout the Arab and Islamic world for nearly a century and will probably set the political tone going forward. The immediate future will feature a debate among competing interpretations of Islamic politics, rather than a struggle between religious and secular parties.

Brian Lehrer Show

I’ve been traveling, and behind on posting. Here’s the link to last wee”s Brian Lehrer show on WNYC, with filmmaker Jehane Noujaim and me discussing the voting in Egypt.

Egypt Votes, Wary and Hopeful

Liberal candidate Basem Kamel inspects a polling station for fraud on Monday. Photo: Rolla Scolari.

(Read the original posting in The Atlantic.)

CAIRO, Egypt — Egypt took another step, albeit a conflicted one, along the trajectory it began in Tahrir Square almost ten months ago. Millions voted Monday in a parliamentary election marred by the ham-handed meddling of the ruling military junta, but with almost none of the widespread violence and fraud that many had feared.

“I’m suspicious, but I have to do something,” said Manar Ahmed, a 27-year-old trying to make a career transition from call center work to tourism. On Monday, she heeded the call of Egypt’s revolutionary youth parties, which urged people to vote and then join the anti-government sit-in at Tahrir now in its tenth day. She wore a colorful orange floral print headscarf and listened patiently as two of her friends explained why they were boycotting the election. Once they finished, she calmly but firmly disagreed.

“We’re going to make many mistakes along the way, but we have to learn from our mistakes,” Ahmed said. “We have to work, and see what happens. We still have to learn how to think.”

Revolutionary parties, consumed for the last ten days in a wave of murderous police violence and the protests it spurred in Cairo, Alexandria, and other cities, faced a quandary. Many of their supporters urged a full boycott. “If we vote, we give legitimacy to the military, which is illegally ruling our country,” said Albert Saber, 26, who refused to cast a ballot even though he had already chosen a line-up of independent pro-revolution candidates in his east Cairo district.

At the same time, the activist party leaders realize that the next parliament will play a key role in a transition to civilian rule, if one occurs, and they understand they might have more influence if they have a voice inside the chamber of deputies as well as on the streets outside.

“The next parliament will have no authority, same as the last one,” said Moaz Abdel Kareem, a youth leader and founder of the Egyptian Current Party, founded by liberal breakaway members of the Muslim Brotherhood youth wing. “This election is fake, a special effect to make it look like the military is working for the people.”

His party suspended its campaign, but its candidates still stumped in polling stations on Monday as part of their unified list, which they named “The Revolution Continues.”

There was a tangible sense in Cairo that street protest was being left behind, dwarfed by voter turnout and the cautious embrace of electoral politics that it heralded. With notably less enthusiasm than they showed during a national referendum in March — the first poll after the Tahrir Square uprising — Egyptians queued for hours, with a mix of muted excitement and markedly modest expectations.

“Change won’t come immediately. It will come step by step,” said Taghreed Ibrahim Hassan, 46. She had come to vote in Shoubra, Cairo’s most densely populated area, with female relatives spanning three generations; she stood out in the voting line for her loud laugh and booming exclamations of enthusiasm.

“This time our voices will count,” she said. “This parliament won’t represent us perfectly, but we won’t be stuck with it forever.”