Egypt’s Free-Speech Backlash

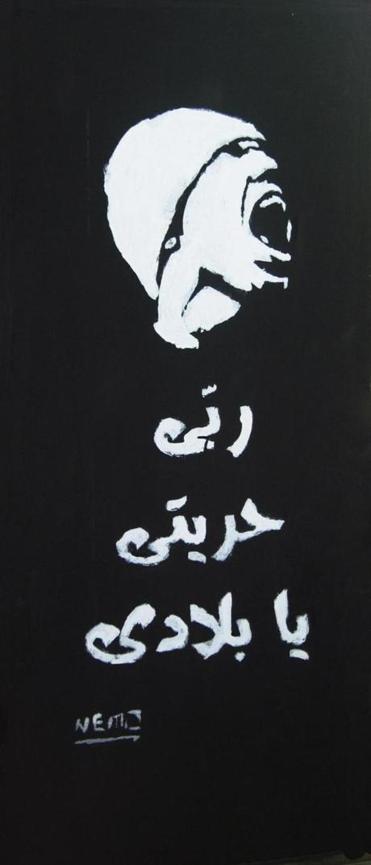

A street poster from Cairo that reads, “My God, my freedom, O my country.” Photo: NEMO.

[The Internationalist column in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

CAIRO — Every night, Egypt’s current comedic sensation, a doctor hailed as his country’s Jon Stewart, lambastes the nation’s president on TV, mocking his authoritarian dictates and airing montages that reveal apparent lies. On talk shows, opposition politicians hold forth for hours, excoriating government policy and new Islamist president Mohammed Morsi. Protesters use the earthiest of language to compare their political leaders to donkeys, clowns, and worse. Meanwhile, the president’s supporters in the Muslim Brotherhood respond in kind on their new satellite television station and in mass counter-rallies.

Before Egypt’s uprising two years ago, this kind of open debate about the president would have been unthinkable. For nearly three decades, former president Hosni Mubarak exerted near total control over the public sphere. In the twilight of his term, he imprisoned a famous newspaper editor who dared to publish speculation about the ailing president’s declining health. No one else touched the story again.

To Western observers, the freewheeling back-and-forth in Egypt right now might sound like the flowering of a young open society, one of the revolution’s few unalloyed triumphs. But amid the explosion of debate, something less wholesome has begun to arise as well. Though speech is far more open, it now carries a new and different kind of risk, one more unpredictable and sudden. Islamist officials and citizens have begun going after individuals for crimes such as blasphemy and insulting the president, and vaguer charges like sedition and serving foreign interests. The elected Islamist ruling party, the Muslim Brotherhood, pushed a new constitution through Egypt’s constituent assembly in December that expanded the number of possible free speech offenses—including insults to “all prophets.”

Worryingly, a recent report showed that President Morsi—a Brotherhood member, and Egypt’s first-ever genuinely elected, civilian leader—has invoked the law against insulting the presidency far more frequently than any of the dictators who preceded him, and has even directed a full-time prosecutor to summon journalists and others suspected of that crime.

The Muslim Brotherhood, as it rises to power, is playing host to conflicting ideas. It wants the United States to view it as a tolerant modern movement that doesn’t arbitrarily silence critics, but at the same time it needs to show its political base of socially conservative constituents in rural Egypt that it won’t tolerate irreligious speech at home. And it wants to argue that despite its religious pedigree, it is behaving within the constraints of the law.

For the time being, Egypt’s proliferating free expression still outstrips government efforts to shut it down. But as the new open society engenders pushback, what’s happening here is in many ways a test case for Islamist rule over a secular state. What’s at stake is whether Islamists—who are vying for elected power in countries around the Muslim world—really only respect the rules until they have enough clout to ignore them.

***

The text on this Cairo street poster reads, “As they breathe, they lie.” Photo: NEMO

EGYPTIANS ARE RENOWNED throughout the Arab world for jokes and wordplay, as likely to fall from the mouth of a sweet potato peddler as a society journalist. Much of daily life takes place in the crowded public social spaces where people shop, drink hand-pressed sugarcane juice, loiter with friends, or picnic with their families. But under the stifling police state built by Mubarak, that vitality was undercut by fear of the undercover police and informants who lurked everywhere, declaring themselves at sheesha joints or cafes when the conversation veered toward politics.

As a result, a prudent self-censorship ruled the day. State security officials had desks at all the major newspapers, but top editors usually saved them the trouble, restraining their own reporters in advance. In 2005, when one publisher took the bold step of publishing a judge’s letter critical of the regime, he confiscated the cellphones of all his editors and sequestered them in a conference room so they couldn’t tip off authorities before the paper reached the streets.

It wasn’t technically illegal to be a dissident in Egypt; that the paper could be published at all was testament to the fact that some tolerance existed. Egypt’s system was less draconian and violent than the police states in Syria and Iraq, where dissidents were routinely assassinated and tortured. But the limits of public speech were well understood, and Egyptians who cared to criticize the state carefully stayed on the accepted side of the line. Activists would speak out about electoral fraud by the ministry of the interior or against corruption by businesspeople, for example, but would carefully refrain from criticizing the military or Mubarak’s family. Political life as we understand it barely existed.

Egypt’s uprising marked an abrupt break in this long cultural balancing act. For the first time, millions of Egyptians expressed themselves freely and in public, openly defying the intelligence minions and the guns of the police. It was shocking when people in the streets called directly for the fall of the regime. Within weeks, previously unimaginable acts had become commonplace. Mubarak’s effigy hung in Tahrir Square. Military generals were mocked as corrupt, sadistic toadies in cartoons and banners. Establishment figures called for trials of former officials and limits on renegade security officials.

In the two years since, free speech has spread with dizzying speed—on buses, during marches, around grocery stalls, everywhere that people congregate. Today there are fewer sacred cows, although even at the peak of revolutionary fervor few Egyptians were willing to risk publicly impugning the military, which was imprisoning thousands without any due process. (An elected member of parliament faced charges when he compared the interim military dictator to a donkey.)

Mohammed Morsi was inaugurated in June, after a tight election that pitted him against a former Mubarak crony. Morsi campaigned on a promise to excise the old regime’s ways from the state, and on a grandiose Islamist platform called “The Renaissance.” His regime has fared poorly in its efforts to take control of the police and judiciary. Nor has it made much progress on its sweeping but impractical proposals to end poverty and save the Egyptian economy. It has proven easier to talk about Islamic social issues: allegations of blasphemy by Christians and atheist bloggers; alcohol consumption and the sexual norms of secular Egyptians; and the idea, widely held among Brotherhood supporters, that a godless cabal of old-regime supporters is secretly plotting to seize power.

Before it won the presidency, the Muslim Brotherhood emphasized it had been fairly elected; the party was Islamist, it said, but from the pragmatic, democratic end of the spectrum. But in recent months, there’s been more than a whiff of Big Brother about the Brotherhood. Supposed volunteers attacked demonstrators outside Morsi’s presidential palace—and then were videotaped turning over their victims to Brotherhood operatives. Allegations of torture, illegal detention, and murder by state agents pile up uninvestigated.

As revolutionaries and other critical Egyptians have turned their ire from the old regime to the new, the Brotherhood also has begun targeting political speech. The new constitution, authored by the Brotherhood and forced through Egypt’s constituent assembly in an overnight session over the objections of the secular opposition and even some mainstream religious clerics, criminalized blasphemy and expanded older statutes against insults to leaders, state institutions like the courts, and religious figures. Popular journalists have been threatened with arrest, while less famous individuals, including children improbably accused of desecrating a Koran, have been thrown into detention. Morsi’s presidential advisers regularly contact human rights activists and journalists to challenge their reports, a level of attention and pressure previously unknown here.

In addition to the old legal tools to limit free expression, which are now more heavily used by the Islamists than they were by Mubarak, the new constitution has added criminal penalties for insulting all religions and empowers courts to shut down media outlets that don’t “respect the sanctity of the private lives of citizens and the requirements of national security.”

The Egyptian government began an investigation of TV comedian Baseem Yousef but dropped its charges after a public outcry.

Egyptian human rights monitors have tracked dozens of such cases, including three that were filed by the president’s own legal team. Gamal Eid at the Arab Network for Human Rights Information charted 40 cases that prosecuted political critics for what amounted to dissenting speech in the first 200 days of Morsi’s regime. That’s more, he claims, than during Mubarak’s entire reign, and more charges of insulting the president than were filed since 1909, when the law was first written.

***

IT’S A WELL-KNOWN PRECEPT in politics that times of transition are the most unstable, and that the fight to establish civil liberties carries risks. The current speech crackdown may just be an expected symptom of the shift from an effective authoritarian state to competitive politics. Mubarak, of course, had less need to prosecute a population that mostly kept quiet.

It could also be a sign of desperation on the part of the Brotherhood, as it struggles to rule without buy-in from the police and state bureaucracy. Or it could, more alarmingly, mark a transition to a genuine new era of censorship in the most populous Arab country, this time driven as much by the Islamist cultural agenda as by the quest to keep a grip on power.

It is that last prospect that makes the path Egypt takes so important. By dint of its size and cultural heft, the country remains a major influence across the Arab world, and both in Egypt and elsewhere, the Muslim Brotherhood is at the front lines of political Islam—trying to balance the cultural conservatism of its rank-and-file supporters with the openness the world expects from democratic society.

There are signs that the Brotherhood wants to at least make gestures toward Western norms, though it remains hard to gauge exactly how open an Egypt its members would like to see. At one point the government began an investigation of Baseem Yousef, the Jon Stewart-like TV comedian, but abruptly dropped its charges in January after a public outcry.

During the wave of bad publicity around the investigation, one of President Morsi’s advisers issued a statement claiming that the state would never interfere in free speech—so long as citizens and the press worked to raise their “level of credibility.”

“Human dignity has been a core demand of the revolution and should not be undermined under the guise of ‘free speech,’” presidential adviser Esam El-Haddad said in a statement that placed ominous boundaries on the very idea of free speech that it purported to advance. “Rather, with freedom of speech comes responsibility to fellow citizens.”

What scares many people, is how they define “responsibility.” A widely watched video clip portrays a Salafi cleric lecturing his followers about how Egypt’s new constitution will allow pious Muslims to limit Christian freedoms and silence secular critics (the cleric, Sheikh Yasser Borhami, is from a more fundamentalist current, separate from but allied with the Brotherhood). When critics look at the Brotherhood’s current spate of investigations and threatened prosecutions, they see the political manifestation of the same exclusionary impulse: the polarizing notion that the Islamists’ actions are blessed by God and, by implication, that to criticize them is sacrilege.

Modern Islamism hasn’t reckoned with this implicit conflict yet, even internally. Officially, one current of the Brotherhood’s ideology prioritizes social activism over politics, and eschews coercion in religious matters. But another, perhaps more popular strain in Brotherhood thinking agitates for a religious revolution in people’s daily lives, and that strain appears to be driving the behavior of the Brothers suddenly in charge of the nation. Their fervor is colliding squarely with the secular responsibility of running a state like Egypt, which for all its shortcomings has real institutions, laws, and a civil society that expects modern freedoms and protections. The first stage of Egypt’s transition from military dictatorship has ended, but the great clash between religious and secular politics is just beginning to unfold.