Where Hamas Goes From Here

Ismail Haniya delivers a speech after the conflict in Gaza. (Ahmed Zakot / Courtesy Reuters)

[Originally published in Foreign Affairs.]

Once again, Hamas has been spared from making the difficult political choice that face most resistance movements when they gain power: whether to focus on the fight or to govern. Since it won the Palestinian elections in 2006 and then took control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, Hamas has been free to pursue a middle course, resisting Israel while blaming its political failures on its cold war with Fatah and on Israel’s blockade. Now Hamas will tout the concessions it won from Israel last week — as part of the ceasefire, Israel agreed to open the border crossings to Gaza, suspend its military operations there, and end targeted killings — as proof that it should not give up fighting. Meanwhile, the outcome should be enough to buy Hamas cover for its poor record of governance and allow it to again defer making tough choices about statehood, negotiations, regional alliances, and military strategy. The group might even be able to use the momentum to supplant Fatah in the West Bank as it has done in Gaza.

Hamas’ recent advance won’t fully mask the organization’s central dilemma, nor will it cover internal rifts about how to solve it. In the American and Israeli media, portrayals of Hamas often focus heavily on the group’s commitment to eliminating the Jewish state. And certainly any fair study of the group should take into account that goal. Yet for Hamas, the end of Israel is more an ideological starting point than a practical program. And what comes after the starting point is unclear: Hamas has never developed a vision of what a resolution short of total victory might look like, nor has it spelled out an agenda for governing its own constituents, despite all these years in power. In part, that is because Hamas is a diffuse and contested movement, whose competing factions all work toward their own self-interest.

Hamas’ top political leadership used to operate out of Damascus but scattered to Cairo, Doha, and other Middle Eastern capitals this year as Syria descended into chaos. Since then, the exiled leadership has clashed publicly with Hamas’ Gaza-based leadership. Khaled Meshal, the organization’s main leader, now based Doha, and his cohort have generally allied with the Sunni Arab states over Iran, welcoming the rise of Islamists in Egypt, in Tunisia, and among the Syrian rebels. Meshal himself has publicly endorsed a truce with Israel based on Israel’s withdrawal to its 1967 borders. The rest of the exile-based leaders have also indicated their willingness to consider a truce, although they say they would consider the deal temporary and would not recognize Israel. Party in response to Hamas’ pragmatism, and partly in acceptance of the reality of the movement’s rising power. Arab leaders finally ended their informal boycott of Gaza, and, in recent months, the emir of Qatar and the prime minister of Egypt paid visits.

Yet the growing stature of Hamas might accentuate, rather than diffuse, the tensions between its exiled chiefs and its Gaza-based leadership. According to Mark Perry, a historian who follows Palestinian politics, Hamas’ prime minister, Ismail Haniya, has endorsed a close relationship with Iran. For his part, Haniya paid a warm visit to Tehran in February, provoking the ire of Arab leaders, who have since given him the cold shoulder, preferring instead to meet with other Hamas leaders. Haniya has expressed no interest in talking about a two state solution and overall, the rest of the Gaza-based leadership has simply grown more uncompromising under the Israeli blockade and now two lopsided wars. It prefers full-throated resistance to any political settlement.

It is unclear whether the differences presage an ideological split or are simply the result of two very different vantage points: inside Gaza, where the leaders have to worry about staying in power, and outside it, where the leaders worry about staying regionally relevant. So far, Hamas has seemed unable to address the issues that divide the two factions, which might explain why the movement has not selected a successor to Meshal, who was supposed to step down this spring. The sides do, of course, have lowest common denominators that hold them together: resistance as the primary avenue to winning Palestinian rights; gaining greater share of Palestinian leadership; and Islamism.

Since Hamas’ creation in 1987, it has tried to match Fatah’s strength. With that goal largely accomplished by 2007, it has moved on to pushing Fatah completely to the sidelines by maintaining a commitment to Islamism and opposition to the Jewish state. By contrast, Fatah has remained secular, and has even agreed to recognize Israel and to conduct an experiment in joint governance with it through the Palestinian Authority. Two decades into the Oslo process, Fatah has little to show for its efforts. Meanwhile, Hamas has not had to face Palestinian voters since 2006. Polling suggests that Palestinians — Gazans in particular — have lost patience with Hamas. But each conflict with Israel gives the movement a new lease on life.

As recently as last week, Israel was describing in breathless terms the latest tepid exploits of the smoky, aging leader of Fatah, Mahmoud Abbas, who is on the verge of obtaining non-member observer status at the United Nations. Israel’s foreign ministry was reportedly circulating policy options to deal with his gambit that included dismantling the Palestinian Authority and withholding its rightful tax revenues, which would effectively subject the West Bank to the same kind of isolation that Gaza has faced since Hamas took power. That would play directly to the long-term goals shared by Hamas’ leaders in Gaza as well as those in exile: to take over from Fatah the role of primary representative of all Palestinians.

What is more, developments in the region have boosted Hamas’ position. This is not the Middle East of the last war, in 2008-09, when, for the most part, the Arab world stood by as Israel subjected Gaza to overwhelming and disproportionate bombing. That conflict killed 1,387 Palestinians and 13 Israelis. Hosni Mubarak’s government in Cairo even assisted the Israeli campaign against Hamas, while the West and Arab world poured money into Fatah’s West Bank government as a counterweight to Hamas. The regional landscape now is entirely different.

Still, despite a warm rhetorical embrace for Hamas, the Egyptian state has yet to significantly change its policy. It hasn’t opened the border with Gaza, nor does it want to do anything that would allow Israel to shift responsibility for Gaza to Egypt. Throughout the cease-fire negotiations, Israel said Egypt would be responsible for keeping the peace. But no matter what Israel says now, the language of the agreement and the reality on the ground make clear that Israel struck a deal with Hamas at Egypt’s insistence, and that Egypt will certainly be no guarantor of Hamas’ behavior. That’s an achievement for the ruling Muslim Brotherhood. As its (and Egypt’s) influence grows, it might be able to promote its preferred exiled Hamas leaders at the expense of the more uncompromising ones in Gaza.

Hamas has other competitors to worry about now. Until the uprisings two years ago, the Middle East’s Islamist movements were mostly on the outside looking in, railing against secular nationalist despots. In fact, Hamas and Hezbollah were the only Islamist movements who could claim to have ascended to power through popular victories at the ballot box. In the pre-uprising Arab world, then, Hamas (like Hezbollah) could plausibly claim some leadership of a regional Islamist movement. No more. The Muslim Brotherhood now governs Egypt. Islamists were elected to power in Tunisia. They have also emerged as power centers in Libya and among the Syrian opposition. Now that Islamists are competing for power in large states, Hamas (and Hezbollah) could shrink to their proper size in terms of influence. This outcome seems even more likely now that Hamas faces a vibrant challenge from jihadi fundamentalists within Gaza who consider Hamas far too moderate.

Hamas has presented itself as a voice for resistance, but as Gaza tries to rebuild and recover from this latest war, the organization will have to grapple with its own authoritarian, corrupt record in power. Its exiled leaders might sound more reasonable to Western ears, but they’re not the ones who actually control territory and manage a government. If it gets what it wants — a central role in Palestinian leadership — Hamas will have to reconcile its own internal factions or else risk a split. On the quickly changing ground of the new Arab politics, Hamas, like other governing movements, will have to articulate an ever-more detailed, constructive program, to convince rather than compel its constituents.

Israel’s New Crisis at Sea

Writing at The Daily Beast, I look at what the future holds for Israel’s Gaza policy now that the Netanyahu government has decided to relax its blockade. I suspect even more challenges to the current legal arrangement which puts both Israel and Gaza in limbo. Read the whole piece here.

If the Netanyahu government translates Sunday’s statement into a substantially more open border with Gaza, they’ll find the calls for a new approach to Gaza just as shrill as ever—perhaps even more shrill now that Israel has backed down on one element of the blockade. What Gazans object to is that Israel claims to have ended any vestiges of occupation of Gaza when it pulled out the Jewish settlements in 2005—and yet, at the same time Israel retains control of Gaza’s sea and land borders.

That’s the nub of the problem, and not the shortage of foodstuffs and medicines. If Israel resolved Gaza’s humanitarian concerns, the Palestinians in Gaza would still be incensed that they can’t travel, import or export goods without Israel’s permission.

In other words, it’s not the cilantro; it’s the siege that’s the problem

Hamas’ Tunnel Diplomacy

My letter from Gaza just went up on Foreign Affairs. In the piece, I describe the similar ways that Hamas has responded to economic and political isolation, in one case with tunnels, in the other case with their diplomatic equivalent. The web of tunnels underneath the Gaza-Egypt border turned an economic crisis for Gaza into a new sphere of influence for Hamas. I liken the approach — improvise and then pretend afterwards it was part of a strategic plan — to the way merchants solve problems.

My letter from Gaza just went up on Foreign Affairs. In the piece, I describe the similar ways that Hamas has responded to economic and political isolation, in one case with tunnels, in the other case with their diplomatic equivalent. The web of tunnels underneath the Gaza-Egypt border turned an economic crisis for Gaza into a new sphere of influence for Hamas. I liken the approach — improvise and then pretend afterwards it was part of a strategic plan — to the way merchants solve problems.

Here’s the thesis:

At first, in 2007, Hamas only tolerated the tunnel economy; but it began to embrace it the following year, legalizing and regulating subterranean trade. Hamas had found a spontaneous solution to the economic crisis that was threatening its rule of Gaza — and, in the process, turned expediency into opportunity.

Opportunism as strategy appears to be the group’s new hallmark. When faced with only bad options to deal with the blockade or its status as a diplomatic pariah, Hamas has behaved as if it chose its predicament, leveraging its position into either greater control over Gaza or greater political influence beyond its boundaries. Desperation, in other words, has become an avenue to power.

Click here to read the whole piece.

A Viable Palestinian State?

A small group of technocrats has doggedly kept at the hard work of designing a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, long after the Oslo Process itself collapsed. Two of its longest serving advocates – Saeb Bamya, the Palestinian economist, and Ron Pundak, the Israeli director of the Peres Center for Peace – tried to answer the lofty (and perhaps rhetorical) question put forth by their host from The Century Foundation: After the Gaza blockade, can Palestine’s economy be viable?

A small group of technocrats has doggedly kept at the hard work of designing a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, long after the Oslo Process itself collapsed. Two of its longest serving advocates – Saeb Bamya, the Palestinian economist, and Ron Pundak, the Israeli director of the Peres Center for Peace – tried to answer the lofty (and perhaps rhetorical) question put forth by their host from The Century Foundation: After the Gaza blockade, can Palestine’s economy be viable?

The two men made a concerted and heartfelt pitch for a return to the ethos of building two states side by side. According to Bamya, more than anything else Palestinians need a “normal business environment,” which requires Israel and the Palestinian Authority to implement the 2005 agreement on access and movement that would free the flow of people and goods between the West Bank, Israel and Gaza. He and Pundak insisted that only a two-state solution could accommodate both Jews and Palestinians.

Daniel Levy, a fellow at the New America Foundation who was a member of Israeli negotiating teams in the latter stages of Oslo and at the 2001 Taba conference, tried without success to pin the two-staters down to specifics: How exactly would they like to Israel and the United States to relate, economically, to Gaza and the West Bank?

I asked Bamya and Pundak at what point they would determine that a self-sustaining Palestinian state was no longer viable. Their answer, it appeared, was that there was no such point. “Everything is reversible if there is political will,” Bamya said. Pundak added, “We are basing everything on the solution of two states.”

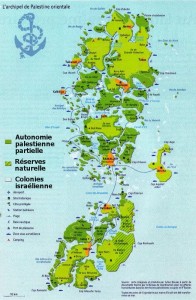

The final questioner, retired Pakistani diplomat Ahmad Kamal, said he hated to appear impolite to the panelists, but said he thought all their assumptions were specious. In the long run, Kamal said, a Palestinian state “dissected” between two unconnected geographical regions, Gaza and the West Bank, would never be sustainable; nor, he said, was an Israel that had hostile relations with its neighbors and which depended on the backing of the United States. “What about the possibility of a one-state solution?” Kamal asked.

“One state won’t happen,” Pundak said emphatically. “We hate each other too much. We will kill each other.”

“I won’t kill you,” Bamya said, provoking some laughter.

“Our grandchildren who don’t exist yet would kill each other,” Pundak earnestly replied.

“Inshallah,” said Daniel Levy, bringing down the house.

Hamas U.

GAZA – Behind the arabesque arches of the five-story university library here, students occupy every available seat, cramming for finals in their humanities classes. Outside, a lucky few nap beneath palm and ficus trees on the cramped urban campus. At lunch, engineering students balance their books upright in the cafeteria and absent-mindedly munch subsidized falafel. This is exam period at the Islamic University of Gaza, charged with the bustle and anxiety of college life.

The first sign that this is a different place from the Western universities it resembles comes when a bell rings in the library. Quickly the students on odd-numbered floors – all men – gather their books and file into the stairwells. Women file in to take their turn. In keeping with a puritanical interpretation of Islamic law, men and women aren’t allowed to study together, so they switch floors every two hours. They lounge in separate student unions and eat in separate cafeterias. At intervals during the day, the call to prayer sounds from the minarets of the campus mosque, and classes come to a halt.

Their strict observance might sound extreme, but the Islamic University is no fringe institution: It’s the top university in Gaza. The majority of students here study secular topics; not all of them are even religious. If you want to get a degree in Gaza, a territory that is home to more than a million people, it’s simply the best place to go.

At the same time, the university is something else again: the brain trust and engine room of Hamas, the Islamist movement that governs Gaza and has been a standard-bearer in the renaissance of radical Islamist militant politics across the Middle East. Thinkers here generate the big ideas that have driven Hamas to power; they have written treatises on Islamic governance, warfare, and justice that serve as the blueprints for the movement’s political and militant platforms. And the university’s goal is even more radical and ambitious than that of Hamas itself, an organization devoted primarily to war against Israel and the pursuit of political power. Its mission is to Islamicize society at every level, with a focus on Gaza but aspirations to influence the entire Islamic world.

In recent decades, as Islamism has grown from a set of isolated radical movements to a fully realized political philosophy, its powerful fusion of intellect, pragmatism, and fundamentalist faith has refashioned societies from the Gulf to Turkey, Egypt to Pakistan. For outsiders who want to understand its power and appeal, the Islamic University of Gaza is probably the best place to begin.

When the Islamic University was founded in 1978, there wasn’t a single institution of higher education in the Gaza Strip. Its founders were members of the militant Muslim Brotherhood, believers that society should be organized according to Koranic principles, and they conceived the university as a sort of greenhouse for their brand of pure, uncompromising Islamism. At the time, Gaza was a freewheeling resort city, its seaside restaurants full of visiting Israelis and Egyptians attracted by Gaza’s famous grilled fish. Secular Palestinians dominated society and the power structure in the 1970s, and scoffed at the prospect of Islamists making inroads. Read the rest of the story in The Boston Globe’s Sunday Ideas section…