Hariri’s Unnerving Interview

Lebanon’s Prime Minister Saad al-Hariri, who has resigned, is seen during Future television interview, in a coffee shop in Beirut, Lebanon November 12, 2017. Photo: REUTERS/Jamal Saidi

[Published in The Atlantic.]

In the Middle East, the parlor game of the moment is guessing whether Saad Hariri, Lebanon’s prime minister—or is it ex-prime minister?—is literally, or only figuratively, a prisoner of his Saudi patrons. In a stiff interview from an undisclosed location in Riyadh on Sunday, Hariri did little to allay concerns that he’s being held hostage by a foreign power that is now writing his speeches and seeking to use him to ignite a regional war. He insisted he was “free,” and would soon return to Lebanon. He said he wanted calm to prevail in any dispute with Hezbollah, the most influential party serving in his country’s government.

Since Hariri was summoned to Saudi Arabia last week and more or less disappeared from public life as a free head of state, rumors have swirled about his fate. On November 4, he delivered a stilted, forced-sounding resignation speech from Riyadh. Michael Aoun, Lebanon’s president, refused to accept the resignation, and Hezbollah—the target of the vituperative rhetoric in Hariri’s speech—deftly chose to stand above the fray, absolving Hariri of words that Hezbollah (and many others) believe were written by Hariri’s Saudi captors.

The bizarre quality of all this aside, the underlying matter is deadly serious. Saudi Arabia has embarked on another exponential escalation, one that may well sacrifice Lebanon as part of its reckless bid to confront Iran.

Foreign influence seeps through Middle Eastern politics, nowhere more endemically than Lebanon. Spies, militias, and heads of state, issue political directives and oversee military battles. Foreign powers have played malignant, pivotal roles in every conflict zone, from Iraq and Syria to Yemen and Libya. Lebanon, sadly, could come next. Even by the low standards of recent history, the saga of this past week beggars the imagination, unfolding with the imperial flair of colonial times—but with all the short-sighted recklessness that has characterized the missteps of the region’s declining powers.

Saudi Arabia, it seems, is bent on exacting a price from its rival Iran for its recent string of foreign-policy triumphs. Israel and the United States appear ready to strike a belligerent pose, one that leaders in the three countries, according to some reports, hope will contain Iran’s expansionism and produce a new alignment connecting President Donald Trump, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and Benjamin Netanyahu.

The problems with this approach are legion—most notably, it simply cannot work. Iran’s strength gives it a deterrence ability that makes preemptive war an even greater folly than it was a decade ago. No military barrage can “erase” Hezbollah, as some Israel war planners imagine; no “rollback,” as dreamed up by advisers to Trump and Mohamed bin Salman, can shift the strategic alliance connecting Iran with Iraq, Syria, and much of Lebanon.

Saudi Arabia, as the morbid joke circulating Beirut would have it, is ready to fight Iran to the last Lebanese. But the joke only gets it half right—the new war reportedly being contemplated wouldn’t actually hurt Iran. Instead, it would renew Hezbollah’s legitimacy and extend its strategic reach even if it caused untold suffering for countless Lebanese. Just as important, a new war might be biblical in its fire and fury, as the bombast of recent Israeli presentations suggests. But that fire and fury would point in many directions. Iran’s friends wouldn’t be the only ones to be singed.

Saudi Arabia’s moves have gotten plenty of attention in the days since Mohamed bin Salman rounded up his remaining rivals, supposedly as part of an anti-corruption campaign. Hariri was caught in the Saudi dragnet around the same time. It seemed puzzling at first: For years, Saudi Arabia had been angry with Hariri and his Future Movement, its client in Lebanon, for sharing power with Hezbollah rather than going to war with it. Riyadh was clearly displeased with Hariri’s pragmatic positions. He had learned the hard way, after several bruising political battles and a brief street battle in May 2008, that Hezbollah’s side was the stronger one. Rather than fuel a futile internecine struggle, Hariri (like the rest of Lebanon’s warlords) opted for precarious coexistence.

Once it became clear that Hariri could do nothing to prevent Hezbollah’s decisive intervention in the Syrian civil war, Saudi Arabia cut off funding for Hariri, bankrupting his family’s billion-dollar Saudi construction empire. It also ended its financial support for the Lebanese army, cultivating the impression that it considered Lebanon lost to the Iranians and Hezbollah.

Now, Saudi Arabia has steamed back into the Lebanese theater with a vengeance. It dismisses Hezbollah as nothing but an Iranian proxy, and, in the words uttered by Hariri in his resignation speech, wants to “cut off the hands that are reaching for it.” In what must be an intentional move, it has destroyed Hariri as a viable ally, reducing him to a weak appendage of his sponsors, unable to move without the kingdom’s permission. Mohamed bin Salman won’t even let him resign on his home soil. If Hariri really were free to come and go, as he insisted so woodenly in his Sunday night interview, then he would already be in Beirut. Even his close allies have trouble believing that threats against his life prevent him from coming home, and the Internal Security Forces, considered loyal to Hariri, denied knowledge of any assassination plot.

The Saudis have fanned the flames of war, seemingly in ignorance of the fact that Iran can only be countered through long-term strategic alliances, the building of capable local proxies and allies, and a wider regional alliance built on shared interests, values, and short-term goals. What Saudi Arabia seems to prefer is a military response to a strategic shift, an approach made worse by its gross misread of reality. In Yemen, the Saudis insisted on treating the Houthi rebels as Iranian tools rather than as an indigenous force, initiating a doomed war of eradication. The horrific result has implicated Saudi Arabia and its allies, including the United States, in an array of war crimes against the Yemenis.

Hariri has clearly tried to balance between two masters: his Saudi bosses, who insist that he confront Hezbollah, and his own political interest in a stable Lebanon. On Sunday night, he appeared uncomfortable. At times, he and his interviewer, from his own television station, looked to handlers off camera. The exchange ended abruptly, after Hariri implied that he might take back his resignation and negotiate with Hezbollah, seemingly veering from the hardline Saudi script. “I am not against Hezbollah as a political party, but that doesn’t mean we allow it to destroy Lebanon,” he said. His resignation does nothing to thwart Hezbollah’s power; if anything, a vacuum benefits Hezbollah, which doesn’t need the Lebanese state to bolster its power or legitimacy.

One theory is that the Saudis removed Hariri to pave their way for an attack on Lebanon. Without the cover of a coalition government, the warmongering argument goes, Israel would be able to launch an attack, with the pretext of Hezbollah’s expanded armaments and operations in areas such as the Golan Heights and the Qalamoun Mountains from which they can challenge Israel. Supposedly, according to some analysts and politicians who have met with regional leaders, there’s a plan to punish Iran and cut Hezbollah down to size. Israel would lead the way with full support from Saudi Arabia and the United States.

Short of seeking actual war, Saudi Arabia has, at a minimum, backed a campaign to fuel the idea that war is always possible. But such a war between Saudi Arabia and Iran would upend still more lives in a part of the world where the recently displaced number in the millions, the dead in the hundreds of thousands, and where epidemics of disease and malnutrition strike with depressing regularity. Short of direct war, Riyadh’s machinations will likely produce a destabilizing proxy war.

If Hariri were a savvier politician, he could have used different words; he could have refused to resign, or insisted on doing so from Beirut. But he is an ineffective leader in eclipse, unable to deliver either as a sectarian demagogue or a bridge-building conciliator. Saudi Arabia’s plan to use him to strike against Iran will fail. Just look at how willfully it has misused and now destroyed its billion-dollar Lebanese asset. It’s a poor preview of things to come in the Saudi campaign against Iran.

Lebanon not just blank slate

A recent workshop at LAU, in which I took part, looked at Lebanon’s role in the Arab uprisings, as a force and actor and not merely as a blank slate. This kind of research is critical, especially since Lebanon has long been on the cutting edge of (often malign) political experiments and trends. The more research and reporting on Lebanon, the better we’ll understand the forces at play here and in the regional neighborhood. The participants shared some useful work that ought to help, in the long run, further our understanding of Lebanon’s role in the region, and put paid to the Lebanese exceptionalist perspective that holds that Lebanon unfolds somehow in isolation from its region.

Strengthened by War, Hezbollah Displays Regional Power

PHOTO: HEZBOLLAH TROOPS IN OUTSKIRTS OF FLITA, JULY 26. SOURCE: WAR MEDIA CENTER.

[Published at The Century Foundation.]

By Thanassis Cambanis and Sima Ghaddar

Hezbollah’s battle against ISIS and like-minded jihadis this month has not attracted as much attention as the ongoing campaigns in Raqqa and Mosul, but it signals an important shift in the Middle East order.

At the end of July in less than a week, Hezbollah quickly dislodged a jihadi stronghold on the border of Lebanon and Syria in the Lebanese town of Arsal. Significantly, Hezbollah, or the Lebanese Party of God, orchestrated a long political and public relations campaign before the offensive, and ultimately put together a military campaign that featured a strange, but effective coalition of government armies essentially led on the ground by a transnational non-state actor.

In this case, Hezbollah quarterbacked a campaign that featured its troops, battle-hardened after five years on the front lines in the Syrian conflict, fighting with support from the Syrian and Lebanese militaries. Hezbollah and the Syrian armed forces have been working together closely for years, but Hezbollah’s partnership with the Lebanese military is more circumspect. Hezbollah and the Lebanese Armed Forces coordinate extensively but zealously guard their autonomy. To boot, the Lebanese army receives extensive support from the United States, which considers Hezbollah a terrorist group—making it all the more pressing for the Lebanese army to keep its distance from Hezbollah.

All these factors make the July offensive in Arsal all the more remarkable. Lebanon’s Sunni prime minister Saad Hariri, who is an outspoken critic of Hezbollah’s regional expansion and role in Syria, ultimately signed off on an operation which highlighted the new balance of power emerging in Lebanon and the Levant.

Hezbollah, arguably, played a more pivotal role than any other Syrian ally in keeping Bashar al-Assad in power when his rule was threatened by the uprising that began in 2011. Since then, Hezbollah has grown more open about its role training and sometimes fighting with militias in Yemen, Iraq, and Syria—a regional expansion that it has undertaken in tight partnership with Iran.

Western Perceptions

The United States and western countries have maintained a hard rhetorical line against Assad and Hezbollah—but at the same time, have clearly decided they prefer Assad’s alliance to the alternative. Early in the Syrian war, Assad and Hezbollah presented themselves as the pluralistic, religiously tolerant bulwark against Sunni Islamist fundamentalist jihadis. That might have been a misleading description in 2012, but now—in large part because of the Syrian regime’s starvation sieges and a Western failure to support non-jihadi rebels—that binary has edged closer to the truth.

Hezbollah’s dual role might make Western governments uncomfortable, and it might force them to undergo rhetorical gymnastics in order to continue their relationship with Lebanese state institutions while ignoring the reality of Hezbollah’s central role in the state and the region. However, it is nonetheless true that Hezbollah has emerged from the disarray in Syria as an indispensable national and regional actor with reach, strategic vision, and capacity. That’s why Hezbollah, and not the Lebanese army, led the campaign to liberate Arsal from jihadi fanatics who have held sway there since 2014.

Hezbollah’s Coalition

On Thursday, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah declared victory in Arsal. “We are doing our victory and expect no victory,” he said. He also ignored the previous day’s press conference in Washington, in which President Trump appeared to believe that Lebanon was fighting to disarm Hezbollah, rather than fighting alongside Hezbollah to disarm Al Qaeda.

The details of Lebanon’s campaign against Al Qaeda, ISIS, and other jihadists are important. So too are the complexities of America’s relationship with the Lebanese state and its institutions, which ought to be reinforced despite their deeply intertwined and sometimes ambiguous relationship with Hezbollah. Even more important, however, is the strategic picture that has been getting clearer and clearer as the war in Syria has progressed toward a resolution that favors Assad’s government and his allies: Hezbollah, Iran, and Russia.

Hezbollah’s campaign in Arsal holds important clues to the regional order taking shape as the war in Syria winds down and new coalitions fill the vacuum created by an America’s growing distance. A mature, transnational Hezbollah quarterbacked a delicate and tense offensive that in practice coordinates two national armies that would appear nearly impossible to place in the same order of battle: the Lebanese national army, whose main supporters these days are the United States and Great Britain, and Bashar al-Assad’s military.

Emerging as a Regional Leader

The coalition in Arsal is a remarkable bellwether for several reasons. It showcases Hezbollah (and by extension, Iran) in a leadership role in an anti-terror coalition. For years, Hezbollah has been trying to persuade Western governments that it is a natural partner in the global campaign against extremist groups that tend to come from the Sunni takfiri milieu. The campaign also formalizes the de facto balance of power in which Hezbollah operates autonomously in both Syria and Lebanon—and in which Hezbollah has enough political sway to set terms for governments in both Damascus and Beirut.

The battle for Arsal holds plenty of clues for the template of Hezbollah’s influence going forward. As a dominant, transnational force, Hezbollah can now hold its own among the region’s nation-states; but as the complex mechanics of its role in Arsal underscore, it is also not a giant, able to dictate terms to those around it. It had to wait and assuage concerns from political and military leaders, in order to persuade the Lebanese army and the Lebanese government to get on board with an offensive that would be perceived in some communities in sectarian terms, as an anti-Sunni attack by a Shia coalition. Hezbollah has displayed strategic patience, biding its time and keeping its eyes on long-term goals that will benefit it organizationally and also help their coalition partners, especially their closest ally and vital sponsor, Iran.

Around this time last year on July 16, 2016 after multiple suicide bombers snuck from the outskirts of the Lebanese northeastern border town of Arsal and targeted the northern village of Al-Qaa, Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s secretary general, said Lebanon is in dire need of an official national defense strategy to fight terrorism. When “others” abandon their responsibilities, he then added, people must assume the responsibility to protect themselves. “The responsibility of the state is our responsibility too,” he said, but always alongside the Lebanese Army and the Lebanese security apparatus.

Since its intervention in Syria, Hezbollah has glorified the role of the Lebanese Army in fighting terrorism in the outskirts of Arsal, but has dictated and directed the terms and conditions of that fight knowing very well the army cannot handle a heavy load and is dependent on both British and U.S. funding. For months now, Hezbollah has independently negotiated settlement deals with an opposition group at the outskirts of Arsal and neighboring Qalamoun region, known as Saray Ahel Al Sham, to relocate refugees and arbitrate with the terrorist groups, Hay’t Tahrir Al Sham (Al-Nusra) and ISIS. However, to no avail. Hezbollah came under attack after Nasrallah recently pledged to clear the town’s outskirts of Syrian militants and rebels with a coordinated air raid campaign by the Syrian regime.

Through all these crises on the border, Hezbollah has steadily built its capacity and deepened its relationships with institutions and governments, making clear that it is de facto a peer, rather than a player in a less significant category simply by dint of being defined as a non-state actor.

When Hezbollah dived headlong into Syria’s civil war, many observers of the Middle East wondered whether the adventurist gamble would the undoing of the Lebanese Party of God.

Instead, it appears that five years of open international warfare have strengthened Hezbollah’s regional position, consolidating its transnational military and political organization. The Party of God entered the Syrian war as a dominant force inside Lebanon; it appears set to emerge from it as a decisive regional player, likely to be as powerful in the coming period as most of the Middle East’s full-fledged states.

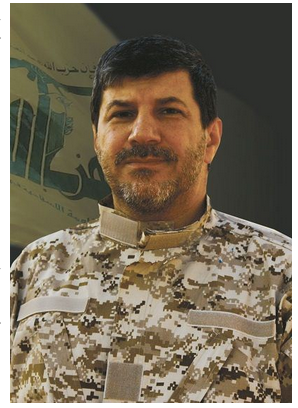

Spy scandal a sign of Hezbollah’s mid-life crisis

The Party of God was set up to fight Israel but is now a large organisation with a massive budget

For five years, Hezbollah has vowed in fiery speeches to exact revenge for Israel’s assassination of its top military strategist in 2010. Each anniversary passed with Hezbollah’s threatened attacks mysteriously foiled: operatives rolled up in Bangkok and Cyprus, and another mastermind murdered near his home in Beirut.

A recent revelation suggests the failure wasn’t so mysterious after all: a Hezbollah official responsible for the revenge attacks might have been on Israel’s payroll the whole time.

The unmasking of the Israeli spy in Hezbollah’s uppermost ranks — leaked in media reports in December and indirectly confirmed over the weekend by Hezbollah’s deputy leader — points to Hezbollah’s biggest long-term problem: its size, wealth and power have made it vulnerable to infiltration, corruption and careerists.

The militant organization, whose name means Party of God, was founded in 1982 to resist the Israeli occupation of south Lebanon but it has grown into an entrenched and wealthy part of the Lebanese establishment. Now in its fourth decade, Hezbollah has more power than its founders could have dreamed.

But no longer a compact revolutionary movement, Hezbollah must now grapple with the consequences of growth and longevity. Some supporters now take Hezbollah for granted while the party’s swelling ranks of cadres and fighters contain opportunists and careerists.

Hezbollah has become a state in all but name. It deploys troops to fight in a foreign war in Syria, it is a power-broker in Lebanon’s national government and it struggles to satisfy constituents who have grown accustomed to a higher, and safer, standard of living. It is subject to the same temptations and vulnerabilities as Arab governments and other legacy actors in the Middle East. The intelligence war with Israel marks just one particularly colorful and acute sign of its approaching middle age.

Hezbollah began to suspect it was compromised after a series of inexplicable setbacks, including the capture of two of its agents following a bombing in Burgas, Bulgaria in 2012. In order to track down the mole, Hezbollah fed false information to one of its officials, Mohammed Shawraba, about weapons shipments in Syria. Israel bombed the false target and after a seven-month investigation, Hezbollah arrested Shawraba.

The double agent might have foiled as many as five planned retaliations by Hezbollah, according to reports that also tied him to the two most damaging Israeli strikes against Hezbollah since the 2006 war: the assassinations of military strategist Imad Mughniyeh in Damascus in 2008 and of Hezbollah technology mastermind Hassan Laqees in Beirutat the end of 2013.

Yet it’s the parade of related cases that have piled up since the last major conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in 2006 that suggest something broader is afoot. Hezbollah revealed in 2011 that it caught some of its operatives cooperating with the CIA, meeting at a Pizza Hut on the edge of south Beirut to sell Hezbollah secrets to the Americans.

A trusted car dealer in southern Lebanon sold senior Hezbollah officials cars that had Israeli GPS trackers in them. He was arrested by the party in 2009.

Another Lebanese man was revealed to have worked as a spy for the Israelis, monitoring traffic on key roads to the Syrian border.

A financial scandal erupted at the same period, in 2009, when a Ponzi scheme collapsed and erased the savings of many of Hezbollah’s middle-class constituents. The scheme was run by Salah Ezzedine, a well-connected businessman (nicknamed Hezbollah’s Bernie Madoff) who had persuaded senior Hezbollah officials to invest their money with him, and who had founded a publishing house named after party leader Nasrallah’s son. Ezzedine lost between $700 million and $1 billion, according to news reports at the time.

A final straw came in 2012 when a senior Hezbollah official who had been embezzling money fled to Israel. Reports suggest he was stealing for his own benefit, pure and simple, but when he was about to get caught he fled to Hezbollah’s greatest enemy with his money and party documents.

All these cases point in one direction: toward more corruption and more Israeli infiltration.

Hezbollah’s initial appeal in the 1980s and 1990s was its incorruptibility and zeal. In a country dominated by kleptocratic warlords, Hezbollah stood out in its first two decades as an organization whose leaders did not care to enrich themselves. Their first priority was to expel the occupying Israelis. Their second was to help their suffering constituents, most of them Shia Muslims displaced by the civil war and crowded into miserable slums on the edges of Beirut. In those first decades, Hezbollah brought sewers, electricity and clean water to south Beirut, and its leaders lived simply.

Today, things are different. At the very top, Nasrallah lives in hiding, and by all reports remains committed to the group’s humble ethic. But the organization he runs is awash in money. After the 2006 war, Iran flooded Hezbollah with millions of dollars to rebuild homes and roads. Since 2011 there’s been yet another burst of spending linked to the war in Syria. Over the objections of many Lebanese — and the grumbling of some supporters who thought Hezbollah should maintain its focus on Israel — Hezbollah dispatched troops to fight on the regime’s side in the Syrian civil war. At first the deployment was kept secret, but today Hezbollah openly sends troops and celebrates its members martyred in Syria. The organization has dramatically increased its spending on fighters and their families and has expanded the size of its military force in order to maintain a deterrent against Israel while fighting in Syria. Hezbollah has become a standing army capable of fighting a war on two fronts where it was once a guerrilla army. That’s an expensive development and not one that necessarily carries the same appeal as Hezbollah did when it was fighting a war of resistance on its home territory against a much stronger Israeli occupation force.

Today, it appears, there are Hezbollah insiders willing to sell crucial secrets to the enemy. There are others who seem happy to siphon money out of the Party of God’s pockets for their own enrichment, just like operatives in all the rest of Lebanon’s notoriously corrupt factions.

In comments over the weekend to Hezbollah’s “Nour” radio station, the party’s number-two, Naim Qassem, said that Hezbollah was made up of fallible humans but was able to contain the “limited” fallout of the spy cases.

“Hezbollah has worked intensely on battling espionage among its ranks and in its entourage. Some cases surfaced, and they are very limited cases,” he said. “There is no party in the world as big and sophisticated as Hezbollah that was able to stand with the same steadfastness.”

That makes sense as spin, and Hezbollah can obviously survive — the question is, with how much damage.

Until the 2006 war, Hezbollah successfully stood apart in Lebanon. It was a Shia organization, but it opposed sectarianism. Even those who didn’t share Hezbollah’s dedication to fighting Israel recognized that the militant group placed that goal over its own power and enrichment.

In its rise to power, however, Hezbollah has relied on support from some of Lebanon’s most corrupt factions, including the Shia Amal Movement and the Christian Free Patriotic Movement.

Today, Hezbollah is a party of the establishment, deeply invested in a Lebanese order that depends on patronage and sectarian balancing. It is unlikely that corruption and spy scandals will unseat Hezbollah from its dominant position in Lebanon. But Hezbollah’s descent from the moral high ground it claims as unimpeachable standard-bearer of the Lebanese resistance seems only a matter of time.

Regional realignment with Hezbollah, Assad & Iran?

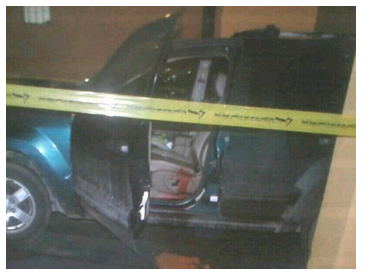

Hassan Laqqis, assassination scene. Source: Al Manar

There’s been lots of talk about the regional consequences of the Iran nuclear deal, and of a realignment as the West realizes that it might prefer Assad in power to a jihadi-dominated rebel government or some version of the current punishing settlement. Ryan Crocker told The New York Times that the US should resume cooperating with Damascus against Salafi jihadis, and various analysts and diplomats have been speculating that Iran, Assad, Hezbollah, and the US share plenty of common interests. Saudi Arabia and Israel stand to lose if the US begins to behave like a mature superpower, collaborating where it sees fit rather than holding itself hostage to the agenda of small allies behave as peers rather than clients.

The latest trigger was yesterday’s assassination of a Hezbollah official in Beirut. (Hassan Lakkis, according to Hezbollah’s Al-Manar Television, played an important role in the fight against Israel; Reuters reports that Lakkis was fighting recently in Syria.) That killing once again raised the question of Hezbollah’s broader direction. Has it provoked a maelstrom of jihadi attacks, retaliation for Hezbollah’s role in the Syrian civil war? Or is the conflict in Syria playing out in the interests of Hezbollah, Assad and Iran?

I think there’s some evidence that three years after a non-violent popular revolt against Assad’s nasty dictatorship, Assad has finally managed the shape the conflict he wanted. He wiped out the non-violent resistance, the intellectuals and the pluralists, and continues to mass his firepower against the FSA rather than the jihadists. As a result, the conflict pits an authoritarian but non-sectarian dictatorship against a Sunni rebellion dominated by takfiri jihadists. Hezbollah entered the war supposedly to fight the sectarian jihadis over there before they made it over here, a la George W Bush. It sounded facile then, but now it sounds true; each time there’s a bomb of assassination in Lebanon, it adds credence to Hezbollah’s claim that it’s on the side of a Middle Eastern order that tolerates multiple faiths and power-sharing, while on the other side Saudi and other Gulf money is supporting extremists who want to recreate the 7th Century Caliphate. Self-serving, but perhaps, true.

We’ve seen hints of change:

- An increase tempo of back-and-forth attacks in Lebanon.

- Stronger desire by Lebanese national institutions to contain the crisis.

- Reports that the US has shared intelligence with Lebanon in order to protect Hezbollah from attacks.

- A real push – in Track 2 and perhaps Track 1 diplomacy – to make the January talks in Geneva really amount to a negotiation for a settlement in Syria.

- The Iranian nuclear deal, which could calm anxieties about the regional Iran-Saudi cold/hot war, and allow for some tit-for-tat that could reduce global interest in the Syrian theater.

What should we look for as signals of a coming, substantive change?

- Rhetoric from Hassan Nasrallah that opens the door to a frigid détente with the US on some issues.

- Continuing restraint by Hezbollah in its response to attacks and assassinations.

- Agreements or accords that result from the vigorous outreach by Iran’s foreign minister to the leaders of the Arab countries in the Gulf.

- Offers, even totally rhetorical ones, from Assad to cooperate with the US against the jihadi groups in Syria.

The interim Iranian nuclear agreement could easily collapse (Marc Lynch writes here about the enormous potential but also the need to remember that it could all come to naught), but it’s a major opening. Iran has always been a more natural geopolitical ally for the US than the tiny oil-rich monarchies of the Arabian peninsula. It’s hard to imagine a full realignment without an internal shift in the governance of Iran, but perhaps, that could occur with a political shift short of regime change. The most likely outcome is incremental, with Iran and the US finding more avenues of cooperation but stopping short of an open embrace. But even the prospect of a cooling in the US relationship with absolute monarchs of the Gulf and the hawkish establishment of Israel, in favor of a more pragmatic policy that leaves room to cooperate with all the region’s heavyweights, has prompted a panic in Riyadh and Israel. That anxiety suggests it’s a very real prospect, and one that in the long-term would serve to cool down the region.

How much to worry in Lebanon, once more?

REUTERS PHOTO

After today’s bombing at the Iranian embassy in Beirut, how much should we worry that the war in Syria will engulf Lebanon? First, the usual caveat: I live here, and I have a vested interest Lebanon remaining viable and stable, so discount my analysis accordingly.

Nonetheless, nothing so far has changed my fundamental view that the major players in Lebanon want to preserve the existing order here, as combustible as it is. The attackers presumably come from the jihadist strain of the Syrian opposition; they have little invested in the Lebanese status quo and are willing to upend it. But the major actors with organizations in Lebanon, including the Sunnis who support the Syrian rebels, as well as the Hezbollah constituents who support the Syrian government, benefit from the truce in Lebanon. Beirut especially serves as a neutral area where all parties communicate with each other, raise funds, and do their political work.

Iran’s immediate accusation of Israel supports this view: if Iran wanted to raise tensions, it would point at jihadists or Lebanese factions allied with the Syrian opposition. Instead, it pointed at Israel (just like Hezbollah did after the Dahieh bombing in August), a convenient and unifying enemy. Blaming Israel is a calming gesture; even if Hezbollah and Iran suspect a local or Syrian Sunni network, it deflates tension to pin the attack on Israel. And if Iran genuinely has evidence or believes Israel is responsible, that’s all the better insofar as it minimizes the risk of hostilities taking root beyond Syria’s borders.

In coming weeks, we should watch the rhetoric of Hassan Nasrallah; if he repeats his previous positions on the Syrian war, as I expect, that will signify that Hezbollah maintains its interest in a calm Lebanon. We also should watch the retaliation; small attacks against centers of jihadist activity would remain with the limited framework that, again, minimizes the chance of escalation.

Today’s attack is certainly a worrisome development, since the apparent suicide bombers struck a diplomatic target. It will increase anxiety among all people in Lebanon, and will especially worry the civilians living in the Dahieh, who already suffered an indiscriminate attack in August that killed 20 people and wounded more than 100. These are not good things. But they don’t guarantee that war will engulf Lebanon either. For that to happen, the established parties here – in particular Hezbollah and the Future Movement – would have to radically change their cost-benefit analysis. So far, I don’t see that happening. Lebanon’s future holds more simmering violence, like the back and forth bombings, assassinations, and occasional skirmishes we’ve seen so far in the Bekaa, Tripoli and Beirut; but not, I expect, outright conflict.

Why the Hezbollah Blacklisting Is Pointless

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

Today, the European Union designated Hezbollah’s “military wing” a terrorist group.

Aside from the fact that the very notion of a separate military wing is an absurd fiction, and that the designation has almost no chance of influencing Hezbollah’s behavior, is there any reason to care?

I would argue that yes, there is; terror designations carry real consequences — if not the ones their authors intend. On balance, I believe that when Western countries blacklist groups they define as terrorist, it harms their own policy aims much more than it does the targeted group. Talking to “terrorists” is political unpopular, but also necessary. It’s one of many tools required to deal with violent non-state actors, along with intelligence work, policing, force, and economic levers.

In the case of Hezbollah, the European Union will now join the U.S. and member governments like Britain in making it all the more difficult to find political solutions to the imbroglios of the Levant. Hezbollah is a major combatant in Syria, while at home in Lebanon it’s the largest and most influential elected political movement.

Hezbollah’s behavior is often frustrating (to its Lebanese rivals as well as to Western governments), and it has been credibly linked to violent plots, political assassinations, and pedestrian organized crime like drug dealing and money laundering.

Naturally, the European Union would like to find ways to curtail Hezbollah’s reach, especially after the group was found responsible for a deadly bombing in Bulgaria and a foiled attack in Cyprus.

But what does a terrorist designation achieve, and at what cost?

First, it eliminates communication with Hezbollah, putting even further out of reach meaningful diplomacy on the Syrian conflict and on Lebanon. It also necessitates foolish gymnastics for states that continue their relationship with the Lebanese government as if Hezbollah weren’t the primary power within that government. Effectively, it amounts to a blanket ban on dealings with Hezbollah, since the Party of God does not make any distinction between its military, political and social work; the organization is seamlessly unified, its fighters as distinct from the supreme leadership as America’s Pentagon is from the White House.

Second, it ties the EU’s hands in acting as a regional broker. How can the EU leverage its power across the Levant’s many conflicts if it won’t talk to one major player, and in fact has taken the step of branding it a terrorist group while leaving alone other factions who engage in similar violence?

In a reality where Hezbollah is a key central player, it makes little to no sense to erect a cone of silence around them (already some governments, like Britain, don’t talk to Hezbollah officials, following the U.S. lead). Any significant political accord in Lebanon must include Hezbollah, just as any political resolution of the Syrian conflict will have to include Iran and Hezbollah, along with the other states that sponsor the rebels and the government. Any other approach is simply a denial of reality and doomed to fail.

Third, the designation will hardly dent Hezbollah. Already Hezbollah operatives linked to violence or terror plots in the West are subject to prosecution in Western courts. Already, Hezbollah’s operations in the West are underground. If agents of Hezbollah are raising money for the group by trafficking narcotics in South America, or are training sleeper cells in Germany, how will the designation stop them? These already are secret, illicit operations; law enforcement and intelligence work might thwart them, but not blacklists.

Logic and experience both teach us that politics requires buy-in from the major stakeholders; that’s even more true in conflict resolution. You don’t make peace with your friends. You can’t influence a war — or an unstable polity like Lebanon — without points of entry to all the major players. It simply doesn’t work.

Historically, blacklists have never worked. Studies have shown that in a small proportion of “terrorist” groups are eliminated by force, but in the vast majority of cases when they give up violence, it is because of a political settlement.

In the case of Hezbollah (like Hamas and a plethora of Iranian institution before it), the blacklisting Western governments are setting themselves up at best for embarrassment and hypocrisy, and at worst for failure.

Ultimately, they will either let conflicts simmer on and do nothing about them (as they largely have in Syria), in which case blacklisting is just one element of a general diplomatic withdrawal. Or else they will get involved with political negotiations, talks, and maybe an agreement that will require them to make deals with the very groups that they earlier designated as beyond-the-pale terrorists with whom any parley whatsoever is unacceptable. When reality prevails, the Western governments end up in tortuous talks through intermediaries, or else they simply ignore their entire directive.

There is almost nothing gained from a terror designation other than the public relations bounce and perhaps some domestic political credit with the tough-on-terror crowd.

But only politics and long-term strategy stand a chance at limiting Hezbollah violence and shifting Hezbollah’s political priorities. It’s unlikely that a smart Western policy would result in a behavior change from Hezbollah, but it’s guaranteed that a terror designation won’t do the trick — and in fact, will only further limit the West’s poor options.

How does it play out for Hezbollah?

Kelly McEvers did this piece on Monday for NPR, in which she asked me about Hezbollah’s long-term chances here. The World followed up with questions about how Hezbollah’s involvement affects the risk of a regional war. There’s a lot of talk in Lebanon about whether Hezbollah’s all-in gambit on Syria will hurt the Party of God long-term. One side holds that killing fellow Arab Islamists rather than Israelis will prove a harder sell to the constituency over the long haul, while the polarizing sectarian fight will make Hezbollah more insecure, and therefore weaker and less predictable, once the regime in Syria falls or conclusively loses control of half the country. The other side sees a Hezbollah constituency fully on board for the fight in Syria, a constituency that understands the Takfiri Sunni fundamentalists to be a major threat not only to Hezbollah and the Shia but to the flawed model of mutual if grudging toleration under which Hezbollah, Assad and many other groups, including minorities and many Sunnis, have thrived.

I’m leaning toward the second interpretation. Sure, there’s a danger of wider war, and sure, there’s now a slightly greater possibility that it all backfires for Hezbollah. On the other hand, consider that the group has continued an uninterrupted expansion of power and intense popular support from its loyalists through the war of the camps in the 1980s, when Hezbollah battled its fellow Lebanese Shia Amal Movement; the hyperbolic years of Sobhi Tufayli’s leadership; its entry into politics; the expulsion of Israel from South Lebanon and thereby the removal of one key factor motivating Hezbollah’s support; the withdrawal of its patron, Syria, from Lebanon in 2005; the 2006 war with Israel; and the May 2008 battle with March 14. So let’s consider that Hezbollah has unchallenged dominion internally in Lebanon (it can’t rule alone, but no one can contest its hegemony either), and that it more or less alone writes the rules — so it might well emerge from this gambit in Syria still in control of Lebanon. The contours of its role would change, especially if the Assad regime falls, or Syria is de facto partitioned. But Hezbollah is unlikely to find itself disarmed, or dislodged from the center of Lebanese power, or bereft of supporters.

Hezbollah and Syria, on Newshour

How much of a watershed were Hassan Nasrallah’s comments on Saturday night? I’ll elaborate on these thoughts in a full piece soon, but my take-away is this: Hezbollah’s open embrace of the war in Syria doesn’t change everything, but it’s a big deal, and it makes the regional situation more combustible. Nasrallah welcomed Lebanese to fight on either side of the Syrian conflict, so long as they don’t extend the battled back into Lebanon. And he said that the war was entering a critical new phase, in which Hezbollah’s ability to fight Israel — the group’s core mission — was threatened by the insecurity of Assad regime in Syria. Hezbollah will heretofore treat the threat to Assad with the same priority that it treats Israeli aggressions. These are major commitments, but they don’t actually mark a change in behavior; Hezbollah has been acting on these principles since the conflict in Syria accelerated. And Nasrallah has the freedom to speak as intensely as he did in part because he knows there’s no direct Western military intervention in Syria in the offing, and because he knows that Israel shares with Hezbollah an interest in avoiding a direct confrontation over the Israel-Lebanon border.

I discussed some of these points in a Sunday afternoon appearance on BBC Newshour, which will be available for a few days at this link.

Iran’s Vietnam?

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

ARSAL, Lebanon — For more than a year, leaders in Lebanon have anxiously eyed the murderous civil war in Syria, wondering whether it would leap across the border and engulf the small, fractious country. And yet, it is Lebanon that now has jumped decisively into the fray, with Hezbollah’s help apparently crucial to the Syrian regime’s strategy and survival.

Uniformed Hezbollah fighters openly patrol the northern reaches of Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, fighting on either side of the increasingly porous border with Syria. Rocket and mortar teams target Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters a few miles away, and Lebanese Hezbollah infantry fighters crisscross the “Shiite villages” surrounding the city of Qusayr just across the border in Syria, which now forms one of the pivot points of the conflict.

The fighting around Qusayr has brought into the open the parlor game over whether Iran and Hezbollah are active combatants in Syria’s war. In an April 30 speech, Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah hinted at greater involvement from the Lebanese paramilitary group in Syria, warning that the regime had “real friends” who would prevent Syria from “fall[ing] into the hands” of the United States and Israel.

The thunder of artillery fire in the mountains flanking the Beqaa Valley, like the spate of no-longer-hidden Hezbollah funerals, make clear that Hezbollah and its Iranian sponsors have crossed a Rubicon. They are now fully vested factions in the Syrian civil war, and they’re committed to an open and escalating fight.

Not 20 miles from Hezbollah’s position as the crow flies, FSA fighters flee across the border to the Sunni village of Arsal, nestled north in the Beqaa Valley in the mountains separating Lebanon and Syria. They make no distinction between the Syrian army, Hezbollah, and Iran — because, they say, they get shot at by all three.

“We could have common interests with Hezbollah, but they’re attacking us. Now there are grudges, which we will have to settle after the war,” said Shehadeh Ahmed Sheikh, 24, a self-described mortar man in the FSA. He was sitting cross-legged on the floor of an unfinished home in Arsal. Sheikh had brought with him 16 members of his extended family after their house in Qusayr had been destroyed earlier that week; as we talked, they squatted around him in the dwelling, which they had been assigned to by Arsal’s mayor.

Like many Sunnis in the area, he referred to Hezbollah, whose name means “the Party of God” in Arabic, as Hezb al-Shaitan — “the Party of Satan.”

By supporting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to the hilt, Hezbollah and Iran are risking their hard-won reputation as stewards of an anti-Israel and anti-U.S. alliance that transcends sect and nationality. Syrian combatants increasingly understand the war in sectarian terms: On one side there is the Sunni majority; on the other side, other sects and a small group of Sunnis that have made common cause with the Alawite regime.

Western diplomats estimate that a few thousand Hezbollah fighters are involved in the Syrian fighting. Close observers of the group, which carefully guards its operational structure, say that they mistrust any precise numbers. But if Hezbollah has sent hundreds, or even a few thousand, of its best-trained fighters to Syria, that deployment certainly represents a significant percentage of its fighting force. During its 2006 war with Israel, the highest estimate of Hezbollah fighters killed was about 700, with the group’s own official death toll closer to 300.

Sunnis are increasingly framing the conflict as a sectarian jihad. The influential Lebanese Salafi cleric Ahmad Al-Assir has set up his own militia, suggesting his fighters would be just as willing to confront Hezbollah in Lebanon as they already are to travel to Syria to fight alongside the rebels there. Supporters of the regime and Hezbollah point out that the rebellion tolerates Sunni fundamentalist extremists whereas Assad and Hezbollah rely on a time-tested alliance of minorities, including Alawites, Christians, Druze, and Shiite Muslims. The propaganda of both sides has sharpened a narrative of the Syrian conflict as a struggle between Sunni extremists and old-style authoritarians, who at least protect the minorities they exploit. Deadly identity politics have taken root, and people on both sides of the conflict see it more and more as a matter of survival. Sheikh, the young Sunni fighter, planned to return to battle as soon as he settled his family: “We cannot go back to the way things were before.”

* * *

On the eve of the uprisings just three short years ago, many Arab analysts observed half-jokingly that the most influential state in the Arab world wasn’t Arab at all — it was Iran, awash in oil revenues and ready to lavish cash on a region in the throes of an increasingly hot Sunni-Shiite cold war. Sunni monarchs and dictators fretted about a “Shiite Crescent” linking Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Hezbollah. Tehran, for its part, strutted triumphantly across the Arab stage, bragging about an unstoppable “Axis of Resistance” oiled with ideological fervor and the supreme leader’s bank account.

What a difference a few uprisings can make. Today, Iran’s involvement in Syria has all the makings of a quagmire, and certainly represents the Islamic Republic’s biggest strategic setback in the region since its war with Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein ended in 1988. Syria’s conflict has begun to attract so much attention and resources that it threatens to end the era when Iran could nimbly outmaneuver the slow-moving American behemoth in the Middle East.

Iran — already reeling from sanctions — is spending hundreds of millions of dollars propping up Bashar al-Assad’s regime. In the murky arena of sub rosa foreign intervention, it’s impossible to keep a detailed count of the dollars, guns, and operatives the Islamic Republic has dispatched to Syria. Westerners and Arab officials who have met in recent months with Syrian government ministers say that Iranian advisers are retooling key ministries to provide copious military training, including to the newly established citizen militias in regime-controlled areas of Syria. “We back Syria,” Iranian General Ahmad Reza Pourdastan reiterated on May 5. “If there is need for training we will provide them with the training.”

In private meetings, Iranian diplomats in the region project insouciance, suggesting that the Islamic Republic can indefinitely sustain its military and financial aid to the Assad regime. To be sure, its burden today is probably bearable. But as sanctions squeeze Iran and it comes under increasing pressure over its nuclear program, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) might find the investment harder to sustain. The conflict shows no signs of ending, and as foreign aid to the rebels escalates, Iran will have to pour in more and more resources simply to maintain a stalemate. If this is Iran’s Vietnam, we’re only beginning year three.

The cost of Tehran’s support of Assad can’t entirely be measured in dollars. Iran has had to sacrifice most of its other Arab allies on the Syrian altar. As the violence worsened, Hamas gave up its home in Damascus and its warm relationship with Tehran. Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood-dominated government has also adopted a scolding tone toward Iran on Syria. On Egyptian President Mohamed Morsy’s first visit to Tehran, he took the opportunity to blast the “oppressive regime” in Damascus, saying it was an “ethical duty” to support the opposition.

Gone are the days when Iran held the mantle of popular resistance. Popular Arab movements, including Syria’s own rebels, now have the momentum and air of authenticity. Iran’s mullahs finally look to the Arab near-abroad as they long have appeared at home — repressive, authoritarian, and fierce defenders of the status quo.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Iran’s commitment to Assad has put the crown jewel of its assets in the Arab world, Hezbollah, in danger. Just a few years ago, a survey found that Nasrallah was the most popular leader in the Arab world. Along with other members of the “resistance axis,” Hezbollah mocked the rest of the Arab world’s political movements as toadies and collaborators, happy to submit to American-Israeli hegemony. Today, however, it has sacrificed this popular support and enraged Sunnis across the Arab world by siding with a merciless dictator.

Hezbollah used to try to cultivate allies from all sects, so that it wouldn’t seem to be pursuing a purely Shiite agenda, but it now appears in the eyes of the Arab world to have cast its lot — hook, line, and sinker — with a brutal minority regime in Syria over a popular, largely Islamist movement. A Pew survey last year found that the group’s popularity was declining in predominantly Sunni countries such as Egypt and Jordan, while Lebanese Sunnis and Christians also increasingly soured on the party.

In the border town of Hermel, usually secretive Hezbollah fighters have openly mobilized. They fight on both sides of the border, protecting a ring of Shiite villages in Syria that connect Damascus to the Alawite heartland. An untold number of Hezbollah fighters have been killed in Syria — so many that the movement has stopped keeping the funerals secret and has even released videos of some of the martyrs. “We bury our martyrs in the open,” Nasrallah said in his recent speech. “We are not ashamed of them.”

Hezbollah positions in Hermel were shelled on May 12, and the Sunni jihadist Nusra Front reportedly claimed responsibility. In their rhetoric, Lebanese politicians have sought to downplay the sectarian nature of the fight in Syria, and there are plenty of individuals who say they have chosen sides out of interest or ideology, rather than sect. Yet to most of its participants, the conflict has taken on an undeniably sectarian hue: an almost entirely Sunni rebellion, against a regime supported by the majority of Syria’s other sects.

“There’s no difference between Hezbollah, the army, and the Syrian regime,” scoffed Mustafa Ezzedine, a driver in Arsal who was recently dragged into the conflict as a literal hostage, kidnapped because he was a Sunni Muslim by a Shiite clan that wanted one of its own kidnapped members released. It doesn’t matter that among his guests at a recent, lazy hashish-fueled afternoon tea was a member of that same rival clan: sectarian politics have little regard for personal views. For residents of the Beqaa Valley, the war in Syria has already drifted across the border, and they fear it could get worse quickly.

The regional stakes are high as well. On at least one occasion, the Syrian conflict has cost an Iranian military commander his life. In mid-February, a shadowy IRGC officer responsible for overseeing Iranian reconstruction projects in Lebanon who went by the names Hessam Khoshnevis and Hassan Shateri was killed on the road from Damascus to Beirut. Iran put out the story that Israel assassinated their man, but Western and Arab officials told me they had seen reliable intelligence reports that it was a Syrian rebel ambush.

A who’s who of Lebanese politicians paid condolences at the Iranian embassy, and Hezbollah’s number two, Naim Qassem, delivered a long tribute to the fallen IRGC offer at a memorial service in an underground theater in Beirut’s Hezbollah-controlled southern suburbs. It was the latest sign that Hezbollah is willing to risk everything in supporting the Syrian dictator — and that Iran just may ask its Lebanese ally to fight to the end, or go down with the ship.

“We would be nothing without Iran!” Qassem thundered in his tribute. “Others hide the foreign funds they receive. We proudly open our hands to Iran’s gifts. What the resistance needs, they provide.”

Iran & Hezbollah in Syria, on Ian Masters Show

Ian Masters spoke with me about the deepening war in Syria and its implications for the outside powers investing in the conflict. Syria’s civil war is increasingly a reflection of power struggles between the Sunni-Monarchical alliance (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE, Jordan, Turkey, Israel, the US, Lebanon’s March 14, the Syrian rebels) and the Shia-Resistance axis (Assad’s ruling coalition, Iran, Iraq, Hezbollah, Lebanon’s March 8, various Arab minority groups). Here we talk mostly about how the conflict affects Hezbollah and Iran, but the bigger picture is that — unfortunately for Syrians — the civil war is definitively deepening into a regional proxy fight as well.

Hezbollah Goes All In?

Matthew Bell did a piece on The World this week about Hassan Nasrallah’s latest speech. In short, has Hezbollah gone all in? And why? You can listen to the conversation here. Quick points: Hezbollah felt compelled to more openly address its involvement in Syria after the big Qusayr offensive of the last month. But this isn’t so much a turning point. The turning point came last fall, when Hezbollah, and Iran, decided not to hedge their bets but rather to fully side with the regime. Now the “Axis of Resistance” stands to lose a lot more when or if Assad falls — but they could well have invested in pro-resistance alternatives.

Hezbollah’s Role in Syria

Old friend Aaron Schaachter put me on the radio on Friday to ask what we know about Hezbollah’s latest maneuvers as the Syrian civil war deepens and spreads. I talked about Hezbollah’s spreading involvement in the conflict, which includes so many outside actors (US, Turkey, Qatar, KSA, Iran, most Lebanese factions, and more) and the dangers for Lebanon as Hezbollah finds its interests threatened by the collapse of the Syrian state. You can listen to the discussion on The World on WGBH/PRI here.

Discussion: Hezbollah’s Changing Strategy?

Google Plus hosted a hangout on Friday to talk about whether Hezbollah’s tactics are changing. I joined Gareth Porter, Ali Gharib and Josh Hersh to talk about the latest European cases against Hezbollah, the debate over terror-listing, and the question of Hezbollah’s motives. The conversation was good, full of healthy skepticism. Hersh made smart points about how little is actually known about Hezbollah, and most of us agreed that it was hard to ascertain why Hezbollah would get involved in assassination plots and terror attacks on civilians at this particular point in its history. We also for the most part agreed that putting Hezbollah on Europe’s terror list would accomplish little. Where we departed was on our view of the evidence — I see accumulating data that connects Hezbollah to plots and killings, although I have questions about the logic at play, while Gareth Porter seemed convinced that there was no actual evidence at all connecting Hezbollah to crimes since and including Rafik Hariri’s murder in 2005.

You can watch the whole half-hour conversation here.

Hezbollah Returning to its Roots?

The bus destroyed in the attack in Burgas, Bulgaria on July 19th, 2012. (Stoyan Nenov/Reuters)

Originally posted at The Atlantic.

The Lebanese Shi’ite militant group, now blamed for a July attack on a busload of Israeli tourists in a resort city in Bulgaria, is once again striking far beyond its home country’s borders.

Hezbollah, a growing body of evidence suggests, is back in the business of international operations after a long hiatus — striking out not only at military or official targets of its sworn enemies, but also, this time, at civilians. Bulgarian officials said on Tuesday that they could connect Hezbollah to the July 2012 bombing at a Black Sea resort that killed six civilians (five Israelis and their Bulgarian bus driver) along with one attacker. The results of Bulgaria’s investigation, if they bear out, add credence to a pattern that has slowly taken shape over the last seven years, ever since Hezbollah was first indicted for a political assassination in Lebanon and later accused of strikes on Israeli targets abroad. The Party of God, once eager to forswear tactics considered terrorist, appears to be tilting back into their embrace. The culmination of this transformation, or return to origins, could have serious consequences.

Observers of Hezbollah have kept track of the organization’s enduring ability to strike beyond Lebanon’s borders and its deep connections in Western diaspora communities. Still, Bulgaria’s claim that two of the alleged Hezbollah operatives carried real Western passports, from Canada and Australia, provides hard evidence. US officials have always worried about Hezbollah operatives with Western passports, but have never made any credible claims about the number of cells with military training that are believed to reside outside Lebanon.

The deliberate investigation of the Bulgaria bombing could heighten alarm about Hezbollah. Last year Hezbollah was accused in plots against Israeli targets around the globe, some foiled ahead of time (Bangkok, Baku), some botched in execution (India, Georgia), and some lethal, like the one in Bulgaria. Perhaps Hezbollah is frustrated by its own weakness; since 2008, it has sworn to retaliate against Israel for the assassination of Hezbollah’s military mastermind, Imad Mughniyeh. Yet more than four years have passed, and Hezbollah has failed in any plots against high-profile Israeli targets. Hence, perhaps, the targeting of Israeli holidaymakers instead.

Now, evidence from these cases is emerging at a time when the Lebanese party-cum-militia is feeling more threatened – and perhaps more militarized – than at any point in more than a decade. Hezbollah fighters have been actively involved in the Syrian civil war, on the regime’s side, another departure for an organization that for two decades has styled itself a national resistance movement, and has portrayed all its fights as defensive stands against Israel. In Syria today, Hezbollah can make no such claim for its fighters. Furthermore, if Syria decided to retaliate directly at Israel for its recent strike, Hezbollah would be the most efficient vehicle through which to do so.

Western intelligence and security officials have longed worried about Hezbollah’s presence among the Lebanese diaspora, which numbers somewhere between 10 and 14 million. Plenty of Lebanese abroad support Hezbollah politically. Some are known to engage in fundraising and other types of nonmilitary support. What’s not clear is how many of these dual nationals have any time of military training, or any role as sleeper or sabotage cells. The Bulgarian revelations suggest that Hezbollah might have some real strategic assets sprinkled in the West.

Since the massive attacks on Jewish targets in Buenos Aires in 1992 and 1994 (which Hezbollah denied but to which it was tied with conclusive evidence in Argentine courts), Hezbollah for a long time avoided kidnappings and terrorist spectaculars. But there’s growing evidence that that policy changed in 2005 with the assassination of Rafik Hariri. Hezbollah has denied any blame for that murder, resorting to increasingly improbable evasions of responsibility. Still, it was a political assassination, and deplorable as it was it didn’t mark a return to attacks on random civilians. Last year’s plots, however, if they are conclusively laid at Hezbollah’s doorstep, do amount to a substantive pivot.

Hezbollah has argued since the mid-1990s that it should be treated as a liberation movement, accorded the status of a quasi-state. It has claimed to behave within the norms of nations, concentrating after 1994 on military targets in its fight with Israel and making a plausible claim to proportionality vis-à-vis Israel’s use of force against Lebanese civilians.

One benefit of this approach for Hezbollah has been Europe’s refusal to list it as a terrorist organization. Hezbollah remains the dominant player in Lebanon’s government and the single-most powerful political and militia organization in Lebanon. While American diplomats by law can’t even talk to Hezbollah members, most Europeans have maintained relations.

Terror-listing is an inherently symbolic exercise; despite the financial sanctions it carries, the designation does little to change behavior and it reduces the political maneuver room of all involved. To what extent has the US listing of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard as a terrorist organization altered its behavior? (For that matter, what difference does it make when foreign states brand the Pentagon “terrorist?”) But if Hezbollah is going rogue, or returning to its rogue roots of the 1980s, it will hurt the group over the long run, as it loses the access it has won in the Middle East and in Europe, and squanders what credibility it earned beyond its immediate following. Hezbollah will remain a quasi-state, but a rogue one.

Today, Hezbollah faces tremendous pressure as its patrons in Syria are on the verge of a state collapse. The Sunni resistance movement that might take over the embattled country detests Hezbollah nearly as much as it does Bashar Al-Assad. So Hezbollah faces the prospect of regional isolation and a strategic dismemberment, with the loss of the hinterland long afforded by Syria

The best-case scenario is that the machinations of outside players in Syria, including Hezbollah’s, don’t alter the wider status quo: that what happens in Syria stays in Syria. Increasingly, however, that seems like a fragile supposition. Already four outside forces have their own guns more or less in the game: Turkey and Israel against the regime, Iran and Hezbollah for it. Plenty more players are sending money or weapons in: the United States, Qatar, Kuwait, Russia, along with other wealthy figures and factions around the region.

Would this imbroglio ignite a regional conflagration? Iran’s threats, like Syria’s, ring hollow, but aren’t without cause for concern. With so many outsiders in the mix, and so many partisan groups already fighting inside Syria, all it takes is one miscalculation. If Hezbollah already has activated secret cells to foment international attacks, making what appears to be several attempts across the world to hit Israeli targets, that marks another destabilizing escalation. It’s a volatile mix, and the more threatened Hezbollah and the Assad regime feel, the more likely they are to make wild moves – attacks guaranteed to provoke international retaliation, or actions that they themselves will come to see as mistakes. There’s no guarantee that we’re headed for a regional war, or a spate of international attacks spawned by Syria’s conflicts – but there’s more cause today than ever before to worry.

How the Arab Uprisings Left Hezbollah Behind

[Published in The New Republic.]

Hassan Nasrallah has always been more sophisticated than the caricatured nightmare featured in the breathless propaganda of Hezbollah’s many enemies. Even at his most noxious he usually managed to present himself as a man of principle. That’s why it was almost sad to see Nasrallah this week pandering like an old-time Arab despot to public anger over the misbegotten Prophet Mohammed YouTube clip.

“America, which uses the pretext of freedom of expression needs to understand that putting out the whole film will have very grave consequences around the world,” Nasrallah said at a Hezbollah rally on September 17, one of the exceedingly rare occasions on which he appeared in public since he went into hiding during the 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon. “The world should know our anger will not be a passing outburst but the start of a serious movement that will continue on the level of the Muslim nation to defend the Prophet of God.” Though the message sounds militant, it was actually just a flailing attempt to catch up to developments elsewhere in the region. Hezbollah, which used to set the Arab world’s trends, now finds itself forced to opportunistically jump on the latest global Islamist bandwagon.

In fact, Hezbollah’s embrace of the controversy over the video marks a final stage of its speedy evolution from revolutionary militant resistance movement to Machiavellian establishment power center. Lebanon’s Party of God once literally threw bombs at those who stood in the way of its ideology, attacking powerful enemies like America and Israel as well as smaller rivals at home. Today, Hezbollah represents the very sort of power it used to oppose. It dominates Lebanese politics as the majority party, choosing the prime minister; it commands a formidable standing army; its complicity in domestic political assassinations no longer is credibly debated; and it remains comfortable with its deep, compromised embrace of Bashar Al-Assad’s criminal regime in Syria.

There’s no mystery here: Hezbollah has become essentially conservative, fearful of the status of its political interests and financial and military networks. The very fact that Nasrallah felt compelled to risk emerging from his underground safe haven suggests that he fears very seriously for his organization’s future. It’s a remarkable change for a movement that was once confident in its ideological rigor and in its ability to earn unparalleled popular support in the region.

IN THE FIRST two decades of Nasrallah’s stewardship, Lebanon’s Party of God transformed itself from a potent but small militant group, best known for spectacular terrorist attacks, into the driver of the Axis of Resistance, crafting a widely appealing message of nationalism and fearless self-reliance built on an uncompromising opposition to Israel and the United States. Just two years ago, Nasrallah was still crowing about an open war with Israel and was still reaping the political benefit of being seen as the sole Arab leader to stand up to the U.S. and Israel.

Today, of course, his critical patron in Syria is teetering, threatening to vastly curtail Hezbollah’s military power, and his source of money and weapons in Iran is distracted by sanctions, a feeble economy and its nuclear showdown with the West. More importantly, the Arab world is awash in genuine retail politics. Indeed, what ultimately broke Hezbollah’s monopoly on popular legitimacy—what ultimately put the Axis of Resistance to rest as a meaningful political or ideological bloc in the Middle East—were the Arab revolts.

Like any establishment power with too much to lose, Hezbollah has kept a distance from uprisings that empower competitors. Still, there is no denying that those rivals have risen throughout the region; fire-breathers and populists have taken position all along the political spectrum from the Islamist right to the secular-anarchist left.

In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood embraces many similar views to Hezbollah, without the call to violence and regional war. There are Salafi extremists running political parties, and there are secular nationalists who sound every bit as uncompromising as Hezbollah when it comes to Israel. To round out the picture, there are voices that oppose violence and endorse diplomacy and pluralistic electoral politics, again along all parts of the spectrum (although sadly, they form a minority). Even Hamas, one of the four pillars of the Axis, has quietly quit its alliance with Syria (and its reliance on Iranian money), gambling that a dignified and principled stand against Bashar Al-Assad will pay handsome long-term dividends in popularity and legitimacy.

Hezbollah, however, calculated that it had no such option. The Assad regime has long allowed Syria to serve as Hezbollah’s rear staging area. Weapons transit through the Damascus airport to Hezbollah training camps and depots. In times of war, trucks can ferry all manner of material into Lebanon from safe havens in Syria. Without Syria, Hezbollah could find itself isolated in the tiny confines of Lebanon, where about half the population detests Hezbollah and its project. For now, Hezbollah’s hard power is undiminished, but the future doesn’t look so secure for the Party of God.

And so, backed into a corner, Hezbollah has responded to the radical transformation of Arab politics much like American policy makers, improvising on an ad hoc basis. Hezbollah has doubled down on its anti-Israel and anti-American credentials, but has abandoned the more inclusive nationalistic part of its resistance credo that arguably propelled its meteoric rise and sustained power. Nasrallah used to unabashedly endorse any populist Arab movement that opposed dictatorship at home or Western ambitions abroad. Now, Hezbollah seems to pick and choose the occasions when justice matters: Yes for the Shia of Bahrain, less so for the citizens of Egypt, and not so much for the Sunnis of Syria. When Israel was occupying southern Lebanon or bombing its villages, and U.S.-backed tyrants were oppressing much of the region, the sense of a powerful, monolithic enemy united support behind Hezbollah. The new reality is patently more complex, with none of the old bugbears solely to blame for the Arab world’s woes. Without a villain, Hezbollah’s fundamental recipe for power and legitimacy loses its yeast.

Of course, Hezbollah has never become explicitly or exclusively sectarian. It has managed to maintain a tight, six-year alliance with Lebanon’s largest Christian party, Michael Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement. But this has never been an especially durable strategy. The contradictions are profound and irreconcilable. To some, Hezbollah is a pan-Arab guerilla front against Israel. To some it is a dogmatic Shia religious movement that sincerely embraces Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s theocratic theology. And to some, it is a shrewd and pragmatic political actor that knows how to make the trains run on time. Yet, it cannot be all of these things at once.

Hezbollah has never been free of such tensions and Nasrallah has always managed to masterfully hold the movement together despite them. As the disconnect has grown wider, however, the false narrative that Hezbollah uses to bridge the gap has grown ever more tenuous. It’s getting harder for even Hezbollah’s most committed supported to believe that Syria’s uprising is a foreign, American-backed plot to massacre innocents, create sectarian strife, and impose Israeli hegemony over the Levant. As the civil war next door spills ever more toxically across the border into Lebanon, claiming lives in Hezbollah’s neighborhoods, it has become impossible to maintain the charade of denial. As the nature of the Syrian regime’s brutality (and the cynicism with which Nasrallah has blessed it) begins to sink in, Hezbollah risks ending up looking more and more like a Shia sectarian movement, just another player in a polarized regional struggle.

If history is any guide, of course, Hezbollah will be nimble and adaptive, and use any circumstances possible to turn a bleak outlook to its advantage. Some holes, however, are too deep to climb out of. The fall of the House of Assad might be one of them. And, judging from his flailing, Nasrallah himself seems to know it.

Who is the Father of the Chicken?

Julian Assange’s interview with Hassan Nasrallah told us nothing new about Hezbollah, but it was interesting all the same for the very fact that it took place. Since 2006, Nasrallah has only spoken to one other Western reporter (Seymour Hersh of The New Yorker), and Hezbollah has minimized its contact with the Western media. The Party of God’s position effectively has been that it’s simply a waste of its time and resources to talk to an audience that views it as a bunch of recalcitrant terrorists under any circumstances.

Perhaps Nasrallah calculated that he stood to benefit from a direct address to a Western audience, what with Syria’s government teetering and Hezbollah situated no longer as a defiant underdog but as a status quo power in a transforming Arab world. Or maybe he just felt like he owed a karmic favor to the Father of Wikileaks and his new patrons at the Kremlin, who are underwriting Assange’s new TV show.

Either way, Mr. Wikileaks spoke for almost a half-hour with Nasrallah, and displayed some chops. He confronted Nasrallah about Hezbollah’s inconsistency, supporting all the Arab uprisings except for the one against its sponsor in Syria. He asked point blank about reports that Nasrallah was upset about corruption and a growing taste for luxury among Hezbollah cadres – concerns I’ve heard echoed by Hezbollah partisans.

A smiling Nasrallah replied in his usual confident and measured cadence, which might have come as a surprise to a Western audience that has never has seen a full performance. Syria has always backed the resistance, he said in a simple explanation for Hezbollah’s support of Bashar Al-Assad. About the Jewish state, Nasrallah explained Hezbollah’s long-held position in gentle language: the Party of God would be satisfied if there were one single state for Israelis and Palestinians.

There were only two, small, surprises.

The first came when Nasrallah, in what was either a display of humor or an unwitting security lapse, revealed some of the code words favored by Hezbollah’s fighters: “donkey,” “cooking pot,” and most intriguingly, “the father of the chicken.”

“No Israeli intelligence agent or computer agent is going to understand what the father of the chicken is or why they call him the father of the chicken,” Nasrallah bragged.

Then, in order to prove his mettle to dismissive career journalists, Assange asked a real stumper of a question: if Nasrallah really considered himself a freedom fighter, why didn’t he fight against the “totalitarianism” of a monotheistic God?

Nasrallah’s clearly got a kick out of it. “How could the universe last for billions of years in such beautiful harmony if there were more than one God?” Nasrallah said with a bemused smile. “We don’t fight to impose a religious belief on anybody.”

Hezbollah vs. the CIA

Throughout its history, Hezbollah has proven adept at reinventing itself in times of crisis, defying its challengers to roar back to power after appearing on the verge of marginalization and defeat.

With that caveat, it’s hard to look the current state of play in Beirut as anything but dire for Hezbollah and promising for those who would like to see a weaker “Axis of Resistance.”

Syria’s dictator is on the way out, and Hezbollah looks reactionary and out of sync with history. Hassan Nasrallah has resorted to citing the resistance record of Syria and Iran, as if the only point in their favor is that they’ve stood against Israel and the United States.

Aryn Baker, writing in Time, points out that Nasrallah feted the other uprisings in the Arab world but when it comes to Syria, has “repeated Assad’s tired canard about foreign influences (read: the U.S. and Israel) driving the revolt.”

That double standard doesn’t sit well with a new generation of Arabs who say Hizballah is doing exactly the same thing Nasrallah mocked U.S. President Barack Obama for at the beginning of the Egyptian revolution: supporting a tyrant just because of his stance on Israel. “They call themselves the party of resistance, of justice, but where is the justice?” asks Issa Hammoud, a documentary filmmaker who had been a decade-long member of Hizballah, until he left the group a few months ago in disgust over its pro-Syria policy. “By supporting Assad’s regime they are proving they have no morals.” Perhaps. But Hizballah is also demonstrating that self-interest often trumps values.

Nasrallah also has focused a lot of attention on the efforts of the CIA in Lebanon, some of which apparently have been foiled by effective Hezbollah counter-intelligence. This embarrassment for the CIA, of course, has nothing to do with Hezbollah’s legitimacy. If everyone is doing the jobs they’re supposed to be doing, America and Israel will be trying to spy on Hezbollah and Syria and Iran, and vice versa.

At a moment when Lebanese and Syrians are wondering why Nasrallah won’t put any daylight between his popular movement and Syria’s repressive minority regime, Nasrallah has used the CIA scoop as a monumental distraction.