BEIRUT – THE UTOPIAN GROUP of professors, architects, artists, and white-collar professionals was supposed to be too naïve and elitist to make any headway against the entrenched warlords and clan bosses who have controlled Lebanese politics for as long as most voters here have been alive.

Instead, the upstart campaign called Beirut Madinati — “Beirut Is My City” — nearly scored an upset in May’s city council elections. With barely any money, a few hundred volunteers, and just three months of lead time, Beirut Madinati ran a lively campaign against the corrupt establishment that has literally mired a nation’s lovely, cosmopolitan capital in garbage.

Now, even though the insurgent movement failed to obtain a single seat because of a winner-takes-all municipal election system, Beirut Madinati has set its sights on national politics. Its founders believe that with a passionate, technocratic assault on a status quo that peddles stability at the expense of quality of life, they are belatedly delivering on the promise of the popular revolts that swept the Arab world five years ago.

“Even the word ‘politics’ has negative connotations in Lebanon,” said Jad Chaaban, an economist at the American University of Beirut, and one of the founders of Beirut Madinati. “People are thirsty for a good political dialogue that will change their lives. People are sick of the same old politics, the same old discourse.”

Although it eschews political and ideological labels, the movement is pointed in its attack on the current regime. Its platform enumerated specific proposals to improve public transportation, garbage collection, housing, parks, and more — each plank explicitly countering a government steeped in corruption, controlled by a few ultra-wealthy families, and incapable of delivering even the most basic essentials of daily life. Beirut Madinati’s structure is a radical rebuke to Lebanon’s powers that be as well: Its candidate list was divided evenly by sect and gender, its finances published online, and positions of responsibility are rotated so that no personalities can dominate.

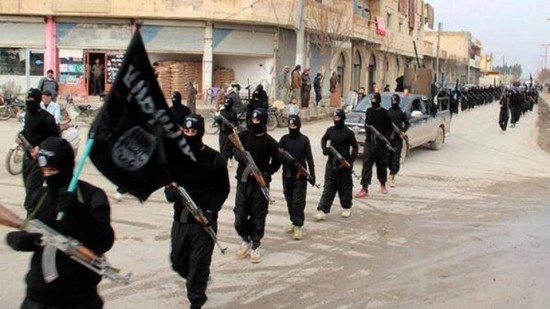

This is the kind of political movement that many activists expected would flourish across the Middle East after the Arab Spring uprisings. But until now, most efforts to create methodical and viable alternatives have been swallowed by violence and repression, usually orchestrated by the very same authoritarian regimes that would be threatened by a credible opposition.

Rubbish trucks drive between a built up pile of waste on a street in Beirut’s northern suburb of Jdeideh in February. AFP/GETTY IMAGES

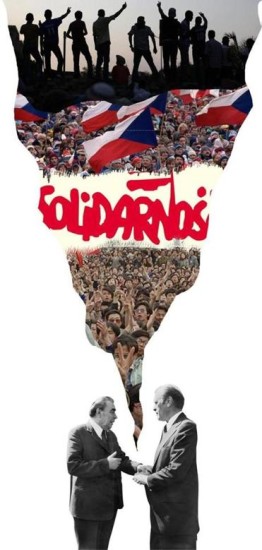

Savvy civic politics is exactly what the Arab uprisings of 2011 promised. Back then, millions took to the streets all over the region, decrying the rotten governance of dictators and corrupt status quo elites. It was not to be, at least not as easily and quickly as the surge of people power first suggested. The old ruling class fought back and, in most cases, was able to thwart popular demands.

Five years later, however, Beirut Madinati is proving the exception — or perhaps, it’s the long-term fruition of a seed planted years ago. In its electoral campaign, the movement cannily avoided the label “political party” and sought to distance itself from Lebanon’s tainted political class. It even spurned alliances with independent politicians who had broken with established political parties and shared Beirut Madinati’s vision of incremental reform focused on tangible improvements to daily life in the city. The idea, according to Beirut Madinati candidates, was to make clear that this movement represented a clean break from business as usual.

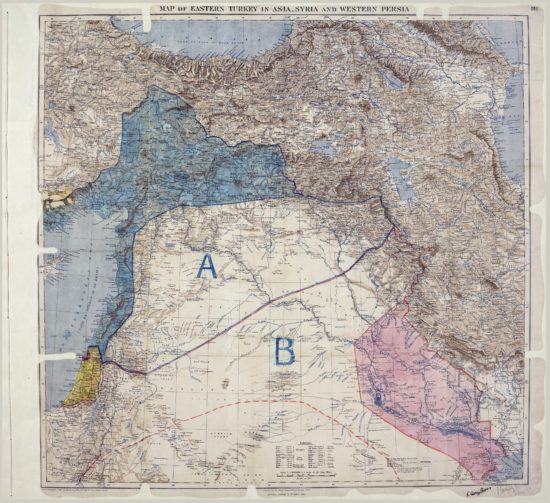

HALF A CENTURY ago, the Arab world witnessed a flowering of political parties and ideologies. Communism and Arab nationalism fueled movements that attracted millions of followers and shaped powerful, modernizing governments. Ba’athist ideology took root in Iraq and Syria. The charismatic Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser sold much of the region on a brand of Arab nationalism that was so persuasive that he convinced Syria and Egypt — two large, important Arab countries with long histories and no common border — to briefly merge under a single unity government. In the 1970s, in response to the failures of the increasingly despotic and erratic secular rulers in the region, Islamist ideas gained political currency.

Since then, for the most part, few new ideas or political parties have emerged and gained traction. In part, the period of quiescence reflected a worldwide ideology fatigue toward the end of the Cold War. But in the Arab world, repressive governments have expended a great deal of energy policing the public sphere to keep out politics of any stripe. Nearly every Arab government invoked a variation on the same formula: It’s either our version of autocracy — or religious radicals.

Fed-up citizens challenged that false binary. The uprisings that began with Tunisia’s 2010 revolt put the first crack in the dictatorial establishment’s stale monopoly on politics. Demonstrations swept the region, frightening rulers everywhere: Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, even the Palestinian Authority. For a moment, no Arab government seemed immune to people power.

But it turned out that the popular movements, with their lack of structure and their modest demands for rule of law and a more fair distribution of wealth, were little match for unscrupulous regimes, and in some cases, zealots and gunmen. Citizen movements in Syria were largely displaced by armed groups once the peaceful uprising deteriorated into a violent conflict. Yemen and Libya followed similar arcs from civil disobedience to civil war. Elsewhere, the old authorities waited out a period of upheaval and then struck back to regain their authority, as in Egypt, where military rulers lurked in the background until they reestablished power through a coup.

Some countries, such as Lebanon and the Arab monarchies of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Morocco, sat out the entire first wave of uprisings. In some cases, like Saudi Arabia, wealthy rulers dispensed generous subsidies and were able to rely on a substantial degree of public legitimacy. Yet, in nearly every case, status quo regimes relied on fear as well, promoting the risk of chaos and violence if existing authorities, no matter how profoundly disliked, were displaced.

In Lebanon, a cabal of hereditary political bosses — many of them former warlords — controls the country, dividing government positions, jobs for their supporters, and profits from graft according to a formula that sets aside a fixed share for each.

Each boss and political party has a power base in one sect: Sunni or Shia Muslims, Maronite Christians, Druze, and so forth. As Lebanon has lurched in recent years from crisis to crisis — it hosts one Syrian refugee for every three Lebanese, has been without a president for two years, and, for a year, didn’t have anywhere to put its garbage — the country’s leaders have engaged in a form of blackmail: Support the existing leaders, or face the prospect of civil war.

It was this threat that Beirut Madinati was most determined to contest. Lebanon’s leaders have spent the years since the civil war ended in 1991 telling voters that their boss-based sectarian balancing act is the only alternative to mass slaughter. Many believe it; memories of the war are still vivid even for people as young as 30.

For good and ill, Lebanon has long served as a model and testing ground for political currents in the Arab world.

Historically — as the supporters of Beirut Madinati are quick to note — Lebanon set toxic trends. Iraq borrowed Lebanon’s dysfunctional model of sectarian power-sharing in 2003, with unhappy results. Some combatants in Syria say their state is so damaged that its only hope for a negotiated settlement is Lebanon’s brand of enshrined paralysis.

But Beirut Madinati is selling a new, most hopeful kind of change. Supporters of the upstart campaign say the results show that Lebanon is finally ready for competitive politics and that at last their country can contribute a constructive example to the region’s political experiments since the Arab Spring uprisings.

“We are not garbage!” said Naheda Khalil, a landscape architect who worked as a volunteer for the campaign. Citizens are smart enough to see through threats from their irresponsible leaders, and she hopes they are now willing to settle in for the years of work it will take to build political alternatives. “We have a long fight ahead. They won’t give up easily.”

THE CAMPAIGN FOR Beirut’s city hall grew out of the summer of 2015’s “You Stink” protests, which flared in response to the Lebanese government’s deadlock over a national waste disposal contract, which, like most public business, is rife with corruption and nepotism. Saad Hariri, a billionaire former prime minister and the dominant Sunni politician, is believed to reap the profits from the country’s garbage collection, the details of which are a closely guarded secret.

Unable to agree on a new landfill when the old one reached capacity, authorities simply stopped collecting the trash. It filled the country’s streets and eventually found its way, by the ton, into rivers, ravines, and poor neighborhoods.

Tens of thousands of Lebanese took to the streets to decry the government’s failure. But the “You Stink” movement quickly faltered. Some of its supporters wanted only to talk about the trash, avoiding any mention of the political dysfunction that caused it to pile up. And others were unnerved at the prospect that a civil movement could topple the government and lead to chaos — a message hammered home daily by ministers and party leaders on the most widely viewed television networks.

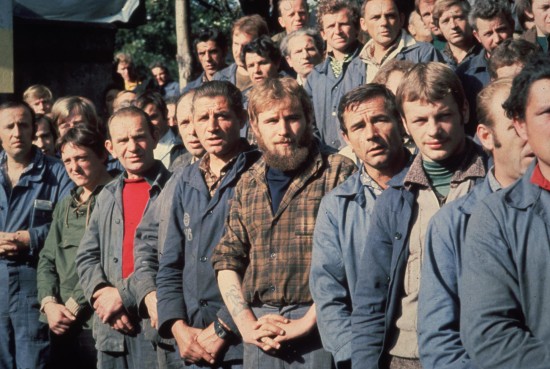

Dozens of veteran activists diligently formed task forces to respond to the garbage crisis, crafting technocratic proposals for recycling, waste sorting, and new ways to devolve garbage handling from the national government to municipalities.

Beirut Madinati candidates and delegates cheered while monitoring ballot counts for the municipality elections after closing the polling stations during Beirut’s municipal elections in May. MOHAMED AZAKIR/REUTERS

When the news cycle moved on from the garbage crisis, the core group of activists kept talking. The country’s warped political system was the real problem, they agreed; if they wanted to improve governance, they’d have a better chance if they obtained actual power rather than relying on protests and white papers. With municipal elections coming up, the activists decided to test-drive their idea. If they did well, they could potentially go national, running for seats in parliament on an anticorruption reform platform.

Lebanon’s bosses were unnerved. Hariri, the Sunni billionaire, controls the Beirut municipality and saw his prestige on the line. Normally bitter rivals, the other sectarian bosses circled the wagons with Hariri, forming a single unified coalition that confused voters by adopting a similar name, “Beirutis.”

Hariri ran his campaign out of an ornate family mansion in the historic city center, which stands as a symbol of Lebanon’s mafia-style corruption. Beirut’s downtown was rebuilt after the war by a Hariri family corporation and remains nearly entirely under the family’s control. In campaign speeches, Hariri suggested that dark forces wanted to destabilize the country.

Although it suffered from accusations of elitism, Beirut Madinati’s campaign depended on unpaid volunteers who congregated in makeshift headquarters at a small rented apartment upstairs from an Armenian restaurant. Hariri is famous for the lavish lunches he serves visitors at his mansion. Beirut Madinati’s members didn’t even have equipment to make their own refreshments and had to dash up the street to buy tea at Lina’s Café.

Its candidates included the locally famous film director Nadine Labaki and a bevy of earnest if little known engineers, professors, architects, and other professionals who seemed genuinely captivated by discussions about subjects like the city’s water infrastructure.

The campaign revived the egalitarian and populist ethos of the region’s uprisings five years ago. Candidates sat in plastic chairs and listened to voter complaints at open forums they organized in the city’s few public spaces.

Symbolically, one such meeting took place on the fringes of the city’s only major public park, a pine forest called Horsh Beirut, which freely admits foreigners but is open to Beirutis only a few days a month.

“We can talk all we like, but nothing will ever change,” observed a teenage pastry chef named Ali, who lives in a poor neighborhood in the south of the city. He wore a pendant with the logo of the Amal Party, a Shia group notorious for corruption even by Lebanon’s low standards.

“I don’t trust them either,” Ali said when asked about the pendant. “We only see them every six years, before elections. They visit our house, promise to pave our street, and never come back.”

BEIRUT MADINATI’S MOST radical innovation has been to face discontent like Ali’s head on, with detailed proposals and an invitation to any interested citizen to join their efforts.

Hariri and his allies pulled out all stops to defeat Beirut Madinati, deploying dozens of paid advocates to every polling station on election day and spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on advertising and, according to independent monitors, illegal bribes to voters. Hariri even summoned some of the group’s candidates to his mansion and offered them slots in his coalition if they would abandon Beirut Madinati, several of the candidates said. They refused.

Supporters of the fledgling movement say they were just as emboldened by the fear Beirut Madinati inspired in the ruling parties as they were by the 40 percent share of the vote that the movement won in Beirut.

In the long game to shift attitudes and power in Lebanon, with its famously stubborn and unscrupulous ruling class, process and persistence will probably matter as much as inspiration.

Over the summer, nearly a hundred members of Beirut Madinati are holding weekend retreats to decide how to proceed. The group is debating whether to register as a national political party and take on Lebanon’s distorted elections laws or focus primarily on the problems facing Beirut. By September, group members said, they will announce a decision and begin the next phase of their campaign to hold the rulers of Beirut, and all of Lebanon, accountable.

“We grew really fast,” said Mona Fawaz, a professor of urban planning at AUB and a founding member of Beirut Madinati. She’s now part of the team sifting through the proposals for the movement’s future. The election campaign raised public expectations very high, she said, and the group needs to be careful to plot a course that allows it to deliver.

“The elections sent a major message, and it’s a very important one: The status quo will no longer be tolerated, and the political parties have one year to redeem themselves before next year’s [parliamentary] elections,” said Ramez Dagher, who writes the popular and critical political blog Moulahazat, which translates to “Observations.”

According to Dagher, in order to grow, Beirut Madinati will have to overcome formidable obstacles, including widespread loyalty to a pernicious but familiar sectarian political order, and voter fatigue. Elections in Lebanon have been known to be postponed sometimes for years at a stretch, which Dagher said could sap the secular antiestablishment movement’s momentum.

Perhaps the biggest taboo the movement has broken is the fear of politics. Until now, most critics of the power brokers in the entire region have treated “politics” as a dirty word, calling themselves activists, reformers, civil society, even revolutionaries — anything but politicians.

“People hate politics now, they think it’s all about dirty deals,” Fawaz said. “We want to reclaim the political, not only to dream about it but to act on it.”

In a region where incompetent and dictatorial rule is the norm, and unaccountable political bosses have grown accustomed to passing power to their cronies or relatives, any reform at all can seem like an impossible prospect. If Beirut Madinati persists, and builds on its unlikely success, it could prove a rare bright spot in the Middle East during a time of authoritarian resurgence and widespread civil strife.