Now What?

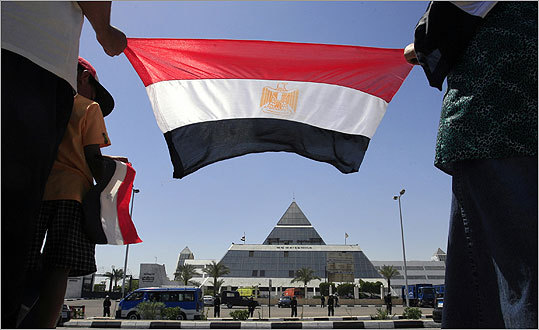

In The Boston Globe I write about the competing schools of thought over what Egypt’s next government should look like. This debate will only get more complicated as the year wears on, with different philosophies vying for predominance on the surface, while powerful and silent vested interests struggle for power below.

CAIRO — Traffic stopped in Tahrir Square during the revolution, but four months later, the torrent of marching humans that briefly made Cairo a world symbol of the thirst for justice has been replaced by the familiar, endless stream of grumbling cars.

The tricolor paint on the city’s trees, applied with gusto in the immediate weeks after President Hosni Mubarak resigned, has already begun to fade. As the wilting heat approaches its summertime averages in the 90s, vendors here do a brisk business selling “I [heart] Egypt” T-shirts, mock license plates commemorating the date of the uprising, and posters of the young martyrs to Mubarak’s security forces.

Schools have reopened; births and deaths are once again registered by Egypt’s ubiquitous bureaucracy; and the machinery of state continues to deliver the basic services that make this nation of 80 million function. The military junta that replaced Mubarak polices the streets and censors the media, though with a touch slightly lighter than Mubarak’s. There are still street demonstrations; on most Fridays, small factions chant in Tahrir Square and distribute leaflets demanding to put figures of the old regime on trial, fix the broken economy, or allow greater freedom to criticize the government.

Most of the nation’s energy, however, has shifted to a new debate: what should come next. Egyptians are realizing that they now face a challenge perhaps even more historic than its revolution. They need to design, nearly from scratch, a legitimate state to govern the most populous Arab nation in the world.

Egyptians are supposed to write a new constitution sometime this fall. And although no one is sure precisely how this will occur — the schedule is controlled by the military junta, which communicates chiefly through updates on its Facebook page — the public conversation has already metamorphosed into raging debate over what the government should look like. The outpouring of public frustration that reached a crescendo in Tahrir Square on Feb. 11 has now moved onto a crowded lineup of television talk shows and the cafes. As youth activist Ahmed Maher put it over a demitasse at the Coffee Bean this week: “Before the revolution, everyone talked about soccer and drugs. Now they talk only about politics.”

End the Addiction to Stability

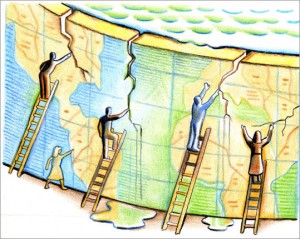

An obsession with “stability” — and an erroneous, narrow definition of the term — has warped American foreign policy, especially in the Middle East. Washington’s struggle to adjust to the rapid transformation of the region in part reflects a calcified mindset that for decades had to account for little change. Now, with the Arab political landscape barely recognizable, American policymakers are trying to adjust quickly. Imagine, American client regimes toppling one by one, while absolute monarchies in the Gulf are taking part in military interventions to unseat one dictator in Libya while propping up another in Bahrain. Some people will argue that all this turmoil amounts to an even stronger argument for stability; I’d say events suggest the opposite. That’s the subject of my latest Internationalist column in The Boston Globe.

America’s main goals in the Middle East have remained constant at least since the Carter years: We want a region in which oil flows as freely as possible, Israel is protected, and citizens enjoy basic human rights — or at least aren’t so unhappy that they begin to attack our interests.

In working toward these goals, the byword and the cornerstone of the entire venture has been stability. Washington has invested heavily — with money, weapons, and political cover — to guarantee the stability of supposedly friendly regimes in places like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. The idea is simple: A regime, even a distasteful and autocratic one, is more likely to help America, and even to treat its own people with a modicum of decency, if it doesn’t feel threatened. Instability creates insecurity, the thinking goes, and insecurity breeds danger.

But the unrest and dramatic changes of the past months are offering a very different lesson. An overemphasis on stability — and, perhaps, an erroneous definition of what “stability” even is — has begun harming, rather than helping, American interests in several current crisis spots. Our desire to keep a naval base in a stable Bahrain, for example, has allied us with the marginalized and increasingly radical Bahraini royal family, and even led us to acquiesce to a Saudi Arabian invasion of the tiny island to quell protests last month. To keep Syria stable, American policy has largely deferred to the existing Assad regime, supporting one of the nastiest despots in the region even as his troops have fired live ammunition at unarmed protesters. In a moral sense, this “stability first” policy has been putting America on the wrong side of the democratic transitions in one Arab country after another. And in the contest for pure influence, it is the more flexible approaches of other nations that seem to be gaining ground in such a fast-changing environment. If we’re serious about our goals in the Middle East, “stability” is looking less and less like the right way to achieve them.

Foreign policy shifts slowly, and it’s hard to replace such a familiar, if flawed, approach to the world. But recent events have strengthened the ranks of thinkers who argue that there may be more effective and less costly ways to press our interests in the Middle East. We could take an arm’s length approach, allowing that not every turn of the screw in the Middle East amounts to a core national interest for the United States — in effect, abstaining from some of the region’s conflicts so we have more credibility when we do intervene. We could embrace a more dynamic slate of alliances that allows the United States to shift its support as regimes evolve or decay. Finally, we could redefine stability entirely and downgrade it as a priority, so that we recognize its value as simply one of many avenues toward achieving US interests.

Read the rest in The Boston Globe.

A Comeback for Isolationism?

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I write about a group of critics I think of as “new isolationists” — cosmopolitan and balanced advocates for a modest, demilitarized, less interventionist American foreign policy. They’re urbane, they care about the world, but they think America meddles far too much — a level of interference that hurts America as much as the rest of the world.

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I write about a group of critics I think of as “new isolationists” — cosmopolitan and balanced advocates for a modest, demilitarized, less interventionist American foreign policy. They’re urbane, they care about the world, but they think America meddles far too much — a level of interference that hurts America as much as the rest of the world.

These old-school realists come at the question from different perspectives but they all share in common a willingness to challenge the received wisdom about America’s approach to the world, and to question whether militaristic interventionism objectively has helped or harmed America’s economy and security. Their critique has matured in the decade since 9/11, and the time is ripe, I think, for us to reconsider their arguments.

There are few ways to get Democrats and Republicans to agree faster than by bringing up national security. Should America invest in a dominant, high-tech military? Should it spend time, treasure, and lives intervening in distant lands and protecting allies? Almost always, the short answer is a resounding yes. Ever since President Franklin Delano Roosevelt browbeat the skeptics and brought America into the Second World War, the country’s foreign policy has been robustly — some would say aggressively — interventionist.

Disagreements have flared only over the details: where to intervene and with what tools. Especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, both right and left took for granted America’s position as lone superpower — and that securing America required complex engagements in global conflicts. There’s mainly a difference in tone between “liberal order building,” Princeton grand strategist G. John Ikenberry’s proposal for how America should reestablish its global position, and conservative historian Robert Kagan’s unapologetic demand for American “primacy.”

This consensus in the world’s leading economy has underwritten an unparalleled military that can strike anywhere in the world. The United States has invested trillions of dollars in projecting power, and immeasurable amounts of political capital fulfilling what it considers its rightful, if exhausting, role. Its policy makers have assumed that America must police disputes from the Straits of Taiwan to the Straits of Hormuz. The next 10 largest militaries combined do not equal America’s in size, expense, or power.

But all that glitter obscures a glaring failure, according to an increasingly energized phalanx of critics. While their prescriptions vary, they all believe America suffers from imperial overreach, fighting abroad to the detriment of prosperity at home. MIT’s Barry Posen has been developing “the case for restraint,” calling for the “stingy” use of military power. Boston University historian Andrew Bacevich argues in his latest book, “Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War,” that America has become a national security state addicted to military interventions that justify its vast defense apparatus. And the University of Chicago’s John Mearsheimer, in the latest issue of the National Interest, charges that American interventionism creates more threats than it neutralizes. They, and a handful of other thinkers, say that America needs to stop meddling far and wide and concentrate on its forgotten, core interests — if it is not already too late. “The results have been disastrous,” says Mearsheimer.

No Big Deal

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

The great international problems of our time beggar the imagination: global warming, pandemics, war crimes, nuclear proliferation, just to name a few. Their complexity confounds the most agile of technocrats, and the stakes involved are high, affecting billions of people living under every sort of government.

For half a century, the conventional approach to these problems has been to build massive international treaties. Intricate worldwide problems demand an integrated approach — a grand bargain, so to speak, that addresses all the winners and losers in a single, encompassing agreement.

This is the animating assumption behind the world’s approach to global warming, for example. To persuade growing nations like China to limit their consumption of fossil fuels, the thinking goes, the world needs a comprehensive framework ensuring that more developed nations make equivalent sacrifices. The climate is simply too large a problem to address piecemeal, or by tinkering with minor symptoms.

But what if this approach results in less progress? What if more modest agreements — on climate change, loose nukes, and other sweeping problems — would yield better results than a long, noble quest for a grand bargain?

Talk to Terrorists

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

Ronald Reagan framed the debate over whether to talk to terrorists in terms that still dominate the debate today. “America will never make concessions to terrorists. To do so would only invite more terrorism,” Reagan said in 1985. “Once we head down that path there would be no end to it, no end to the suffering of innocent people, no end to the bloody ransom all civilized nations must pay.”

America, officially at least, doesn’t negotiate with terrorists: a blanket ban driven by moral outrage and enshrined in United States policy. Most government officials are prohibited from meeting with members of groups on the State Department’s foreign terrorist organization list. Intelligence operatives are discouraged from direct contact with terrorists, even for the purpose of gathering information.

President Clinton was roundly attacked when diplomats met with the Taliban in the 1990s. President George W. Bush was accused of appeasement when his administration approached Sunni insurgents in Iraq. Enraged detractors invoked Munich and ridiculed presidential candidate Barack Obama when he said he would meet Iran and other American adversaries “without preconditions.” The only proper time to talk to terrorists is after they’ve been destroyed, this thinking goes; any retreat from the maximalist position will cost America dearly.

Now, however, an increasingly assertive group of “engagement hawks” — a group of professional diplomats, military officers, and academics — is arguing that a mindless, macho refusal to engage might be causing as much harm as terrorism itself. Brushing off dialogue with killers might look tough, they say, but it is dangerously naive, and betrays an alarming ignorance of how, historically, intractable conflicts have actually been resolved. And today, after a decade of war against stateless terrorists that has claimed thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of foreign lives, and cost trillions of dollars, it’s all the more important that we choose the most effective methods over the ones that play on easy emotions.

Greekonomics

During our vacation in July, I reported a piece for The Boston Globe Ideas section about the economic crisis in Greece, which was just published today. Two questions intrigued me. How much would the collapse of the economy degrade actual quality of life? And had the Greeks proved that market orthodoxy was partly based on a mirage by calling its bluff and surviving?

During our vacation in July, I reported a piece for The Boston Globe Ideas section about the economic crisis in Greece, which was just published today. Two questions intrigued me. How much would the collapse of the economy degrade actual quality of life? And had the Greeks proved that market orthodoxy was partly based on a mirage by calling its bluff and surviving?

The answer, I found, was that average working Greeks were suffering substantial losses, and were bracing for far more in the fall — for starters 5 to 10 percent cuts in real wages and real pensions for many people, in addition to increased taxes. That’s not taking into account rising unemployment, social tension, and macroeconomic changes.

For Greece, the real test comes in the next few months, when the government tries to move ahead with the austerity plan it promised Europe in exchange for the bailout, and Greek unions take to the streets.

What happens next will resonate far beyond this small country’s borders. Greece is about to learn whether a modern state can withdraw entitlements that people have come to take for granted but which the government no longer can afford. For fiscal hawks, this is a harbinger of what could happen to the American economy when, say, the social security system finally goes bankrupt, or when the government no longer has enough money to fund Medicare. For Greeks, it’s something else as well — a kind of identity crisis for a way of life defined almost as a rebuke to contemporary liberal market economics.

Americans, the saying goes, live to work; Greeks work to live. As a credo, it reflects a Greek belief that a worker on any rung of the class ladder deserves security and pleasure in exchange for hard work. It’s not outsized salaries or short workdays that define the Greek model. First and foremost it’s job security: Until recently Greeks struggled to find jobs, but once employed they never feared losing them. A close second is the principle of egalitarian access to the pleasures of life: going out to eat or listen to music on the weekends, and taking your family on Easter and summer vacations.

From the outside, the Greek sense of entitlement is often misunderstood as a desire for some kind of lazy lifestyle. In actuality, though, most of the government and union workers raising hell in the streets work hours as long as any American blue collar or office worker; many of them, in fact, work two jobs — at a bank or ministry in the morning, driving a taxi in the evening. What Greeks have treasured for decades and are now contemplating losing is the kind of job security that most Americans surrendered in the 1970s. All those wasteful government jobs underwrote a vast reservoir of public confidence, and in large measure blessed Greece with a joie de vivre. Small entrepreneurs don’t feel as stressed when the government countersigns their loans and when they know, if the business fails, they still have a stable job at the state water and sewer authority.

New York, Viewed from the Rest of the World

I’ve spent much of the last week covering the Park51 story from the Arab world. The entire affair has attracted far less attention in the Islamic world than one might expect. We put together a story that canvassed global reaction in today’s Times.

I’ve spent much of the last week covering the Park51 story from the Arab world. The entire affair has attracted far less attention in the Islamic world than one might expect. We put together a story that canvassed global reaction in today’s Times.

If the project’s organizers move the site, or cancel it altogether, I’d expect stronger opinions than we’ve seen so far. Same if there’s a major shift in public opinion, or a spate of violent attacks, or nastier rhetoric than we’ve seen so far.

For more than two decades, Abdelhamid Shaari has been lobbying a succession of governments in Milan for permission to build a mosque for his congregants — any mosque at all, in any location.

For now, he leads Friday Prayer in a stadium normally used for rock concerts. When sites were proposed for mosques in Padua and Bologna, Italy, a few years ago, opponents from the anti-immigrant Northern League paraded pigs around them. The projects were canceled.

In that light, the furor over the precise location of Park51, the proposed Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan, looks to Mr. Shaari like something to aspire to. “At least in America,” Mr. Shaari said, “there’s a debate.”

Across the world, the bruising struggle over an Islamic center near ground zero has elicited some unexpected reactions.

For many in Europe, where much more bitter struggles have taken place over bans on facial veils in France and minarets in Switzerland, America’s fight over Park51 seems small fry, essentially a zoning spat in a culture war.

But others, especially in countries with nothing similar to the constitutional separation of church and state, find it puzzling that there is any controversy at all. In most Muslim nations, the state not only determines where mosques are built, but what the clerics inside can say.

The one constant expressed, regardless of geography, is that even though many in the United States have framed the future of the community center as a pivotal referendum on the core issues of religion, tolerance and free speech, those outside its borders see the debate as a confirmation of their pre-existing feelings about the country, whether good or bad.

The “Ground Zero” Imam

Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, leader of the Park51 project (you know, the Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan), kept quiet about the controversy back home during his visit to Bahrain this week. He was on a US State Department trip promoting interfaith dialogue, tolerance, and his long-running project to inject his philosophy of adaptable American Islam into the worldwide Islamic debate. Initially, the State Department tried to shield the imam from publicity, but eventually relented – slightly – by making public one event in each of the three countries Imam Feisal is visiting.

Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, leader of the Park51 project (you know, the Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan), kept quiet about the controversy back home during his visit to Bahrain this week. He was on a US State Department trip promoting interfaith dialogue, tolerance, and his long-running project to inject his philosophy of adaptable American Islam into the worldwide Islamic debate. Initially, the State Department tried to shield the imam from publicity, but eventually relented – slightly – by making public one event in each of the three countries Imam Feisal is visiting.

In Bahrain, I managed to secure my own invite to the majlis of Sheikh Salah al-Jowder. He’s an oddity, a moderate salafist who sits on an interfaith dialogue committee in Manama (it’s interesting that such a thing even exists). There, Imam Feisal talked a bit about the center, because his hosts had a lot of questions.

The latecomers to Sheik Salah al-Jowder’s majlis, or weekly assembly, wished peace upon their cousins and shook all the men’s hands before sitting down on the deep striped sofas that lined the oblong reception hall.

Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, leader of the planned Park51 Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan, was sipping Arabic coffee about an hour before midnight Sunday in Muharraq, a crowded neighborhood near the international airport.

On the first stop of his good-will tour, sponsored by the State Department, Mr. Abdul Rauf talked expansively about religious law, the lessons of Islamic history and his mission to build bridges between the West and the Islamic world — any topic, it seemed, but the controversy that lately has made him famous.

About 20 Bahraini men, in flowing white robes and headdresses held in place with braided leather bands, fiddled with their BlackBerrys, drank coffee and fingered beads.

After Mr. Abdul Rauf had spoken, and exchanged pleasantries with his hosts, one of the Jowder cousins raised his voice.

“I know you have the support of President Obama,” he said, almost shouting to be heard over the air-conditioners. “But why don’t we just change the place, to show that Islam is not there to threaten everybody, that Islam is a religion of peace?”

Imam Feisal is in Qatar now, and will visit the United Arab Emirates before returning to the U.S. in early September. He said he will talk to the American media then. For now, he insists, he wants to focus on the Cordoba Initiative’s outreach project.

A lot of his most controversial ideas – at least in the Islamic world – have to do with his belief that Islam takes a different shape in every host culture. American Islam, Imam Feisal argues to his audiences in the Islamic world, has just as much religious legitimacy as Egyptian Islam, or Persian Gulf Islam, or Malaysian Islam, and so on. He makes his argument quietly, but it’s a position that runs squarely counter to the trends in the Arab world toward a more orthodox view of Islam. Imam Feisal believes that Muslims in Egypt can learn from the way American Muslims interpret their faith, and not just vice versa.

For a sense of those ideas and their origin, you can read Anne Barnard’s fabulous profile of Imam Feisal (on which I collaborated from Cairo). She also parses some of the claims about him circulating in the blogosphere.

Can You Tell a Terrorist to Abandon Violence?

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, it appears that Americans aren’t allowed to interact with listed terrorist groups, even to provide them the kind of assistance that on its face would appear to conform precisely to American policy aims. In the case of Holder vs. Humanitarian Law Project, a group of American activists sought permission in advance before holding workshops to teach nonviolent political negotiation to a group listed as a foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department. In this case, the groups involved were the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, or PKK, the militant Kurdish separatist group, and the LTTE, or Tamil Tigers, in Sri Lanka. The court ruled 6-3 that such assistance would violate American laws that prohibit providing material assistance to terrorists.

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, it appears that Americans aren’t allowed to interact with listed terrorist groups, even to provide them the kind of assistance that on its face would appear to conform precisely to American policy aims. In the case of Holder vs. Humanitarian Law Project, a group of American activists sought permission in advance before holding workshops to teach nonviolent political negotiation to a group listed as a foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department. In this case, the groups involved were the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, or PKK, the militant Kurdish separatist group, and the LTTE, or Tamil Tigers, in Sri Lanka. The court ruled 6-3 that such assistance would violate American laws that prohibit providing material assistance to terrorists.

I will write at greater length about this case later, and the many complicated questions that it raises. But right off the bat, it makes me wonder:

- Are the go-betweens who take messages to listed terrorist groups and report on their meetings to U.S. diplomats now legally liable?

- What happens if a listed terrorist group wants to abandon violence and learn politics? Who is allowed to advise them?

- Do journalists violate the material support law when they interview members of listed terrorist groups and publish their statements?

- When the U.S. government sends out feelers to listed terrorist groups, using intelligence operatives or other means, are they violating the law? Or is the government itself exempt? Or is a secret presidential finding necessary?

- If teaching terrorists about human rights law is equivalent in the eyes of the law to giving money to terrorists, what are the implications for free speech? Have words and money, political speech and military donations, become indistinguishable in the eyes of the law? What further avenues of prosecution would be opened such a finding?

The Supreme Court decision is here. Read the news story and the editorial in The New York Times, and other links on the homepage of the Humanitarian Law Project.

Nonviolence, Hamas Style

Civil disobedience has enjoyed a renaissance among Palestinians, most vividly with Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s call for a boycott against Israel rather than armed resistance. (Adam Horowitz and Philip Weiss describe the “Boycott Divestment Sanctions Movement” in this long essay in The Nation. Matt McAllester theorizes in The Daily Beast about why non-violence has failed to win Palestinian hearts.)

It remains possible that civic and political action will replace rockets and suicide bombings as the weapon of choice for Palestinian activists. So far, though, Hamas doesn’t seem too interested. In conversations I had with Hamas officials during a reporting trip to Gaza in January, I encountered glib jokes and incomprehension rather than any serious engagement with the idea of non-violence.

Hamas had suspended support for suicide bombings against Israeli civilians, but only, officials told me, because such attacks were failing to produce the desired effects – not because they were wrong, illegal or counter-productive.

“There are two paths: the path of Gandhi and the path of Al Qaeda,” Hamas parliamentarian and spokesman Salah al-Bardaweel told me. When I asked him which one Hamas would take he paused and then said: “Al Q-andhi!” He bellowed with laughter at his joke.

He did add more seriously that “there are many types of resistance,” and that Hamas promoted social, political, and cultural efforts along with its military wing. He pointed out that some groups have splintered from Hamas because they didn’t consider it militant enough. Historically, Bardaweel argued, Palestinian organizations that focused exclusively on politics and culture at the expense of armed struggle lost popular support. “We are a resistance group, but we can’t let military actions spoil our entire political plan,” he said.

At a seminar for junior Hamas officials at the House of Wisdom, a think tank chaired by Hamas’s deputy foreign minister, a group of men in their twenties and thirties scoffed when I asked if they could imagine Hamas adhering to the Geneva Conventions and using the tools of non-violent protest.

One, a mid-level Hamas bureaucrat named Ahmed al-Najjar, didn’t even understand the concept. “Non-violence?” he said to me. “What have we ever accomplished by the throwing stones?”

An American colleague described the tactics of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. As the American talked, Najjar leaned over to me and chuckled. “Non-violence in this part of the world is nonsense. What do you want? We should stand in front of the Israelis shouting ‘No, no occupation, go, go, occupation’? Non-violence is nothing. It does not work.”

The Afghanistan Endgame

Brian Katulis at the Center for American Progress and Andrew Exum at the Center for New American Security tangled this week over Afghanistan strategy. Brian said the counter-insurgency community had hoodwinked Washington, and Andrew said that the Center for American Progress hadn’t presented compelling plans for Iraq and Afghanistan. Michael Cohen prompted the kerfuffle when he argued that the left had failed to question the war in Afghanistan and propose credible alternatives.

All of which got me thinking: can the think tank community propel a smart, substance-focused public debate about America’s strategic aims in Afghanistan? I have in mind a probing, impolitic assessment of whether the current tactics can achieve that strategy. CAP invited CNAS to take part in a public debate, which Exum said he we would happily join after returning from a dissertation leave. But I’d like to see these thinkers applying their brains to the big sprawling questions. Think tanks are largely extensions of different power constituencies in Washington, so perhaps it’s naïve, or structurally impossible, to expect them to re-frame the Afghanistan debate so that it includes more than the current two options: leave, or stay and fight, with some debate over the timeline and number of troops.

I expected this kind of vigorous reappraisal in 2009, during the Obama Administration’s Afghanistan policy reviews. However, the government ended up focusing on narrow questions, like how many troops were required to execute a counter-insurgency strategy, and on what timeline American troops should withdraw. The public never heard an airing of the underlying strategic questions:

- What tactics have been most effective at killing, capturing or deterring individuals and organizations whose goal is to conduct terrorist attacks beyond Afghanistan’s borders?

- What is America’s desired end-state in Afghanistan and Pakistan? Is it achievable, especially considering Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s drift away from the U.S. and Pakistan’s internal problems?

- If not, can America disentangle itself from Afghanistan in its tenth year of war there, even without achieving its principal war aims?

- If the U.S. cannot midwife a stable Afghanistan (or Pakistan) then what is the most effective way to combat the international terrorist groups currently thriving in the borderlands of Afghanistan and Pakistan?

These questions are tough, and probing honest answers would probably require the defense and South Asia experts to jettison some of their previous conclusions and criticize the policies of some of their friends and colleagues. But it would be a healthy and illuminating discussion at a moment when the course set largely by General Stanley McChrystal’s report last fall seems not to be yielding the desired results.

One way Afghanistan could end up in a handbasket

This week, my graduate students at the New School ran a simulation of the coming year in Afghanistan. I kept the parameters loose and tracked the scenario closely to reality. (I’ve attached a list of the roles assigned at the end of this post.) They began in the present, April 2010, tasked with finding a way to minimize the amount of casualties and political instability before the summer. In a second round of play, set in July, the scenario stipulated that ISAF had invaded Kandahar without conclusively wresting control of the city from the Taliban. In the final round of play, set in October, the US was tasked with trying to usher in a settlement between the Afghan government and the insurgency.

Keep in mind that it’s only a game, but the results surprised me:

- India and Pakistan reached secret agreements over trade routes and insurgent funding.

- In the game, the U.S. played the most active role in brokering settlements between competing Afghan factions.

- Prompted by payments from the U.S., unsuccessful presidential candidate Abdullah Abdullah formed an alliance with Northern Alliance leader and defense minister Marshal Fahim, and the pair then made a secret deal with insurgent leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

- Ahmed Wali Karzai, joined forces with disaffected Afghans and the CIA to plot a coup and assassination of his brother the president.

- In the final negotiations to set the terms for a new election, Taliban factions and other insurgents won a deal in which they agreed to take part in the ballot without being forced to renounce violence, and without any guarantees that they would honor the results.

- The U.S. was unable to resolve terms for how it would operate and fund a government that included Taliban, especially if the Taliban won the scheduled elections.

Of course, there are countless differences between a simulation game like this one and reality, not the least of which is that players who in real life would have difficulty passing simple messages through third parties can in the game easily converse with one another. Some lessons I took:

- If communications channels opened up, some hostile parties like India and Pakistan could find common ground on incremental details.

- Insurgents had a strong hand negotiating deals with the Afghan government and the U.S.; they could come to favorable terms and then defect as soon as it suited them with few consequences.

- The U.S. was severely constrained by the quality and reliability of its allies. It had no compelling alternative to Karzai. The Abdallah-Fahim-Hekmatyar alliance, far-fetched as it was, was inherently unstable and not likely to result in a stable government that could advance U.S. interests or secure Afghanistan.

- As in real life, it seemed like there were no good possible outcomes, only varying degrees of bad.

- Too many actors with two few constraints have the ability to destabilize Afghanistan and Pakistan. Even a brilliant and well-executed strategy would have difficulty accounting for all the different Afghan factions and regional players.

The players:

| CIA Kabul station chief |

| US Ambassador Karl Eikenberry |

| General Stan McCrystal |

| Richard Holbrooke |

| President Hamid Karzai |

| Ahmed Wali Karzai, President Karzai’s brother, Kandahar strongman |

| Marshal Mohamed Qasim Fahim, defense minister, Tajik Northern Alliance leader |

| Abdullah Abdullah, failed 2009 presidential candidate |

| Mullah Abdul Qayyum Zakir, deputy supreme leader, Taliban/Quetta Shura |

| Sirajudin Haqqani, leader of Haqqani network |

| Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, leader of Hezb-e-Islami militant faction |

| Local Popolzai chieftain, leader of unaligned Pashtun sub-tribe |

| Ashfaq Kayani, Pakistani army chief of staff |

| Lt. Gen. Ahmad Shuja Pasha, director-general of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency |

| Shri S.M. Krishna, External Affairs Minister, India |

| Manouchehr Mottaki, foreign minister, Iran |

| Sergey Lavrov, foreign minister, Russia |

| UN Special Representative Staffan de Mistura (Sweden) |

| UN deputy Special Representative for Politics Martin Kobler (Germany) |

Engaging With Terrorists?

My students at Columbia are investigating American policy toward terrorist-designated non-state actors. They’re talking to American policy-makers, analysts and diplomats about Washington’s approach to intelligence-gathering and deal-making. They’re also looking at the experiences of other governments: Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, members of the European Union. By the time they finish their project in May, they should have some concrete ideas about what works, what doesn’t, and ways that the Uunited States might more effectively promote its national interests.