The Logic of Assad’s Brutality

A child and a man are seen in hospital in the besieged town of Douma, Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, Syria. Picture taken February 25,2018. REUTERS/Bassam Khabieh

[Published in The Atlantic.]

Bashar al-Assad, the president of Syria, might have great contempt for the sanctity of human life, but he is not a reckless strategist. Since 2011, he has prosecuted an uncompromising war against his own population. He has committed many of his most egregious war crimes strategically—sometimes to eliminate civilians who would rather die than live under his rule, sometimes to neuter an international order that occasionally threatens to limit his power, and sometimes, as with his use of chemical weapons, to accomplish both goals at once. When he does wrong, he does it consciously and with intended effect. His crimes are not accidents.

The Syrian regime’s suspected chemical-weapons attack on Saturday in Douma, a suburb of Damascus, suggests that Assad and his allies have accomplished many of their primary war aims, and are now seeking to secure their hegemony in the Levant. But two major factors still complicate Assad’s plans. One is Syria’s population, which to this day includes rebels who will fight to the death and civilians who nonviolently but fundamentally reject his violent, totalitarian rule. The second is President Donald Trump, who has expressed a determination to pull out of Syria entirely, but at the same time has demonstrated a revulsion at Assad’s use of chemical weapons.

Almost precisely one year ago, Assad unleashed chemical weapons against civilians in rural Idlib province, provoking international outrage and a symbolic, but still significant, missile strike ordered by Trump against the airbase from which the attacks were reportedly launched. Assad’s regime was responsible for the attacks and its Russian backers were fully in the know, later evidence suggested, but Damascus and Moscow lied wantonly in their hollow denials.

This weekend, it appears, Assad’s regime struck again. Fighters in Douma refused a one-sided ceasefire agreement, and haven’t buckled despite years of starvation siege warfare and indiscriminate bombing. In what has become a familiar chain of events, the regime groomed public opinion by airing accusations that the rebels might organize a false-flag chemical attack in order to attract international sympathy. An apparent chemical attack followed, killing at least 25 and wounding more than 500, according to unconfirmed reports from rescue workers and the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations. The Syrian government and the Russians have once again blamed the rebels, knowing that it will take months before solid evidence emerges, by which point most attention will have turned elsewhere. The pattern is by now predictable. In all likelihood, solid, independent evidence will soon emerge linking the attacks to the Syrian regime.

Assad already has unraveled the global taboo against chemical weapons, in the process exposing the incoherence of the international community. Syria has exposed the international liberal order as a convenient illusion. Western bromides of “never again” meant nothing when a determined dictator with hefty international backers committed crimes against humanity.

Why now? This latest attack in Ghouta, if it holds to the pattern, makes perfect sense in the calculus of Assad, Vladimir Putin, and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The successful trio wants first and foremost to subdue the remaining rebels in Syria, with an eye toward the several million people remaining in rebel-held Idlib province. A particularly heinous death for the holdouts in Ghouta, according to this military logic, might discourage the rebels in Idlib from fighting to the bitter end. Equally important, however, is the desire to corral Trump as Syria, Russia, and Iran did his predecessor, Barack Obama.

After the humiliating August 2013 “non-strike event,” when Obama changed his mind about his “red line” and decided not to react to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, the Syrians had America in a box. The White House signed up for a chemical disarmament plan that proved a farce. By the time the agreement had unraveled and Assad was back to using chemical weapons against Syrian citizens, the public no longer cared and Obama was busy discussing his foreign policy legacy.

Trump’s Middle East policy remains a mystery. He has long appeared unconcerned with rising Russian power in the Middle East, but today tweeted that there would be a “big price” for Russia, Iran, and Syria to pay. He seems to prefer a smaller U.S. military footprint, talking repeatedly about pulling troops out of Syria and Iraq. He’s savaged the deal that shelved Iran’s nuclear program, and doesn’t appear impressed by the shabby chemical-weapons agreement in Syria. He doesn’t seem interested in a long-term strategic engagement in the Arab world, but he’s also not interested in propping up the status quo. His reaction to the Khan Sheikhoun attack a year ago aligned with these preferences: He abhorred the attack and spoke with uncharacteristic humanity about the children killed by Assad, and ordered a pointed but limited response. He wasn’t interested in escalating or intervening against Russia or Assad, but he also had no interest in pacifying or reassuring them.

One result of Trump’s confusing Syria policy is that Assad and his backers can’t quite be sure what America is planning—a pullout or a pushback. Hence another chemical attack, which will test the range of America’s response and, perhaps, will paint Trump into the same corner where Obama’s Syria policy languished.

For Assad, there is utility in such a feint, and no real risk. In 2013, he and the rest of the region braced in fear for an expected American response, which was widely expected to jolt the regional state of affairs. Assad has learned his lessons since then. No meaningful American response will be forthcoming, no matter how hideous the war crime. America remains deep in strategic drift, unsure of why it continues to engage in the Middle East, and prone to spasms of hyperactivity rather than sustained attention.

Although we can’t be sure—yet—exactly what happened in Ghouta, we can be confident that it was no accident. Assad is determined to cement his grip once again over Syria, no matter how thoroughly he has to destroy his country in order to restore it. And with Putin’s backing, he is determined to thoroughly discredit what remains of the international community and U.S. leadership. They can’t be sure what Trump will do, but their apparent cavalier use of chemical weapons on the one-year anniversary of the Khan Sheikhoun attacks suggests they’re reasonably confident that the U.S. president won’t take serious action.

This most recent attack, as tragic as it is, is no turning point. It’s more of the same from Assad and his allies, as they solidify the grisly, dangerous norms that they’ve been busy enshrining since 2013.

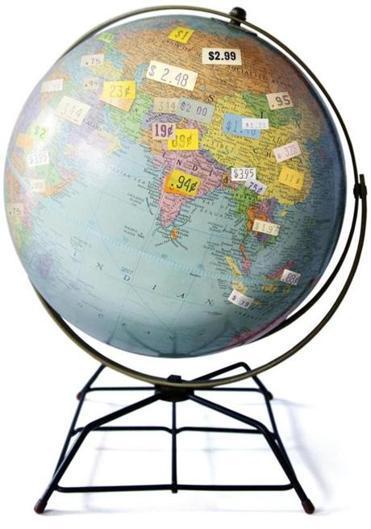

Let’s Make a Deal: Emerging Global Trumpism

Illustration: ROB DOBI FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

DONALD TRUMP came into office promising that his sharp deal-making skills would revolutionize US foreign policy. It sounded like bluster — not much of a change from Trump’s predecessors, who also believed they were negotiating deals for their American constituents.

To many ears, Trump’s vow also sounded unprincipled. Even though American relations with the rest of the world always have had a transactional element, Washington’s overarching goals for most of its history have been broad and moralistic, with a premium on long-term security and prosperity.

Meanwhile, Trump’s initial moves — dispensing with the niceties of alliances and accords, breaking with normal diplomatic practice, avoiding the theater of give and take before critical decisions are made — seemed to reflect his impulsive temperament, not some larger theory of how to promote the national interest.

But after a hectic half-year during which Trump has thrown the US diplomatic handbook out the window, the rough outlines of Trump doctrine are starting to emerge. Even the president’s most vociferous and worried critics (myself included) ought to entertain the prospect that there’s a method to the recent madness in international affairs. Maybe Trump’s wholesale reengineering of America’s approach to the world isn’t just the accidental consequence of a White House managed by chaos theory. Maybe Trump really has an intentional plan to transform the world order itself.

In recent weeks, Trump has begun to articulate what “America First” deal-making means on the global stage. Announcing his withdrawal from the international climate change accord, he emphasized that he represents “Pittsburgh, not Paris.”

Still more telling was his speech in Saudi Arabia, where he assured a select group of pliant allies that America would stop lecturing about rights and responsibilities . He also signaled he would support an unpopular war on Yemen, and take sides with Saudi Arabia in its other neighborhood squabbles with Qatar and Iran, so long as Saudi Arabia adopted America’s counter-terrorism priorities and continued its historical support of the US defense industry. While the president appears to have exaggerated a colossal $110 billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia, the contours of Trump’s deal were clear.

Bald nativism colors the president’s rhetoric, but a clear ideology underlies it. Trump’s government will no longer shoulder a superpower’s burden of maintaining a world order; it will leave that task to others, and reap the short-term windfalls that might come with its collapse. Transactions will no longer be a tactic but the goal itself; each interaction must be a win for the United States — no more short-term compromises to achieve long-term goals. His predecessors made soaring appeals to the aspirations of free peoples. Instead, Trump asks at each and every turn: “What’s in it for us?”

This approach has several virtues for Trump. It can be explained on a bumper sticker, unlike more ambitious policies, which by definition are also more ambiguous. Its gain will come in measurable increments — big arms deals with a set price tag, big savings for American businesses no longer fettered in the international arena by rules and regulations — and not in hard-to-quantify metrics like stability, thwarted terror attacks, or democracy. Finally, the Trump approach is all about the now. How do you sell the American public on achievements like balancing a chaotic Middle East in order to stave off worse future violence, or protecting global shipping lanes, or upholding the NATO alliance?

Trump knows how to sell, and those of us who cherish the international liberal order (which until recently was a public good with profound bipartisan support) must worry that Trump’s foreign policy doctrine could win many adherents in the United States. His maneuvers will be understood to save money, dodge entanglements, and earn respect. So what if they actually do the opposite of the course of a full presidential term? Trump might build the most successful isolationist coalition in American history — in large part because he’s not a pure isolationist.

He wants to retreat from international commitments, and is willing to explode norms and institutions that make the world safer and richer, but he doesn’t want to retreat from the world itself. He’s happy to get involved, piecemeal and opportunistically, to make a buck here and a splash there. In Syria, for example, he has resorted to shows of force that Obama eschewed, twice bombing Syrian government targets, but he’s also shelved most of the sustained efforts by the Pentagon and State Department to actually manage or contain the Syrian conflict. This approach is not pure isolationism, but it is chauvinistic and indifferent to the needs of America’s allies (and the capabilities of its enemies to cause problems). Even as it harms America’s long-term standing and interests, Trump’s approach might well reap some short-term political wins that boost his popularity among Americans who have always been ambivalent about their superpower role.

FOR AT LEAST a century, America has conceived of itself as a “great power,” a primary beneficiary of a world order that it creates and upholds. During some periods of history, the global order is fluid, and it’s every nation-state for itself; in other, steadier times, there’s a firm taxonomy. Major powers set the terms for everyone, and reap most of the benefits. Most smaller powers accept the role of client, while a few maximize their interests by acting as spoilers, refusing the terms of the dominant order and risking a forceful response from the main powers.

Traditionally, America has pursued its interests with an eye on the long term, forgoing quick gains in order to consolidate positions that are perceived as best for American security and prosperity. Strategic patience has governed policy moves that are visionary as well as appalling. America made great sacrifices to rescue Europe during two world wars, and invested impressive resources through the Marshall Plan to ensure Europe’s post-war recovery into a wealthy zone of peace. America was equally long-sighted, if considerably less altruistic, in pursuit of Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine, which gave America a continental scale and ensured its domination of the Western Hemisphere, at an awful cost to indigenous Americans and the political autonomy of its neighboring countries. For good and ill, America was trying to control the game board, not merely to win the next round.

During the Cold War, although American foreign policy was complex, its central stated goal was straightforward: contain communism.

Trump’s emerging transactional doctrine harks back to that Cold War simplicity, after 25 years during which American presidents from both parties struggled to articulate precisely what American foreign policy stood for. The simplicity of Trump’s doctrine might feel familiar, but its innovation is to divorce America’s calculus from any core principle, moral or strategic.

American foreign policy has, since World War II, embraced liberal internationalism. The most important rival view has been classical realism, which would strip away moralistic layers of policy, like democracy promotion and humanitarian intervention, but would still exhort America to engage in promoting a stable world order that safeguards American interests. Realism — as practiced to some extent by states like Britain, Germany, Russia, and China — is less sentimental than liberal internationalism, but it invests heavily in cooperative international institutions, regimes, and agreements that preserve national interests. Meanwhile, from the margins, isolationists argue that America can protect itself without any truck with foreign powers and international accords.

Trump’s approach doesn’t fall neatly into these categories. It’s clearly anti-internationalist, but it’s not isolationist. Its closest historical analogue is the dangerously ambitious and agnostic approach of rising powers like Germany and Japan in the early 20th century, who were struggling to elbow their way into an international order that actively excluded them. There are few parallels of a strong, rich, established power resorted to destabilizing, relentless opportunism.

Unsurprisingly, Trump’s foreign policy doctrine is anathema to liberals, and it’s being executed in a haphazard and dangerous way. But it also draws on some real interests, often overlooked by liberal internationalists — like demanding that NATO allies shoulder their share of communal defense, or calling out Iran on its belligerence, or admitting what has already been a long-time practice: The United States will quickly overlook human rights abuses by countries that are willing to make lucrative deals with American companies.

A cynic might argue that there’s no real danger, since America’s foreign policy was often transactional in the past, and that Trump is simply saying in public what past presidents preferred only to discuss in private. But such insouciance overlooks the novelty of opportunistic transactionalism elevated from occasional tactic to core doctrine.

AS SOON AS America defects from international accords, others will follow suit or step in to fill the void. Some of these accords are informal, like America’s long-term commitment to promoting a balance in the Middle East rather than throwing its lot in wholesale with one side in a regional war. Trump has effectively thrown in his lot with one faction, dominated by Saudi Arabia, and the region is sure to witness an uptick in violence along with an increase in foreign involvement. Others, like NATO or the Paris Agreement, attempt to codify and lock in international cooperation in order to achieve ambitious goals that no single nation can accomplish alone but that benefit all. Without America’s support, it’s unclear whether such initiatives can survive, but by quitting (or in the case of NATO, potentially shirking) America stands to reap the short-term windfalls of the spoiler or the rogue state even if in the long-term it is likely to suffer the blowback as painfully as any nation.

The dangers abroad are manifold. They’ve begun to unfold in the Middle East, as states emboldened by Trump’s transactionalism already are overreaching. Israel’s settlements expand undaunted, and its political leaders (over the objections of its security establishment) are considering the merits of a preemptive war against Hezbollah in Lebanon, which would be disastrous for both Lebanon and Israel. Saudi Arabia, with Trump’s full blessing, is ramping up a war in Yemen that is only accelerating state collapse and terrorism, while pursing a collision course with Iran and any Arab state that deviates from the Saudi line (witness the recent excommunication of Qatar by Saudi Arabia and its partners).

On a global scale, China has quietly stepped into the gap left by the United States, making preparations for a vast web of infrastructure and investment that could make Beijing the key arbiter in East Africa, the Middle East, and parts of South Asia, as well as in the trade routes connecting those regions to China. Russia has asserted itself with new force in its sphere of influence. Rising nations around the world that have played along with international norms will reconsider destabilizing pursuit of self-interest over wider harmony, a state of autarchy and competition that could easily accelerate nuclear proliferation, a breakdown in international trade, and spikes in pandemics, famine and poverty.

A foreign policy that relentlessly maximizes immediate benefits for the United States might have a lot of appeal for Americans, even among constituencies that don’t like Trump. Its short-term results could play well in electoral cycles, before the toxic dividends come due.

At home, Trump’s approach will fan the flames of nativism and isolationism. In recent history, when America turned its back on the world and wished its responsibilities away, cataclysms forced it to reengage, first at Pearl Harbor and then on 9/11. The United States is the most powerful nation in the world. Its actions affect almost everybody on the planet, and, because we all live on the same planet, the actions of others affect the United States. America is dominant, but not all-powerful. It’s a giant on the world stage, but giants and predators do not live in splendid isolation. Their success and survival depend on an ecosystem. If America destroys that ecosystem, it too will suffer the consequences.

Why It Pays to Be the World’s Policeman—Literally

[Published in Politico Magazine.]

One of Donald Trump’s campaign applause lines held that it was time for the United States to quit serving as the world’s policeman and take care of business at home.

Isolationist chestnuts like this are standard campaign fare for a certain kind of conservative; just before he embarked on the biggest expansion of American military interventionism, George W. Bush, too, ran against the idea of “nation-building.”

Set aside for a minute the fact that even during years of unabated war following Sept. 11, 2001, America has done very little nation-building. Forget, also, that it’s questionable just how accurate the shorthand of “world policeman” is to describe America’s role in today’s international security architecture.

The essential fact is that the United States sits at the pinnacle of a world order that it played a central role in designing, and which benefits no other country so much as it does — you might have guessed — America itself.

America runs a world order that might have some collateral benefits for other countries, but is largely built around US interests: to enrich America and American business; to keep Americans safe while creating jobs and profits for America’s military-industrial complex; and to make sure that America retains, as long as possible, its position as the richest, dominant global superpower. Rather than global cop, it’s more accurate to call America the world’s majority shareholder, investing its resources in global stability less out of charity than self-interest.

What this means is that as Trump develops his foreign policy — a dealmaking approach whose ultimate outlines we can only guess at — he will eventually have to walk back his promise or confront its real costs. It’s easy to paint America as the rich uncle whom the world takes advantage of. That caricature certainly resonates with Trump’s voting base. But if Trump really tries to deliver on his promise and walk away from the world, the biggest price is likely to be borne by America itself.

***

The United States and its allies, in the wake of World War II, built a web of institutions that had an ideological goal: to reduce the risk of another murderous global conflagration. The United Nations would serve as a political-diplomatic talk shop that would reduce the chance of accidental superpower war and create avenues for managing the conflicts that did break out. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were designed to minimize the risk of another Great Depression. An acronym soup of other institutions sprang up along the same lines. When memories of fascism were fresh and Washington feared the allure of communism, it made some far-sighted, pragmatic moves. It funded the Marshall Plan for Europe, paying so the continent could recover economically and emerge to become a pivotal U.S. ally–and a profitable market for US companies. U.S. military occupiers in Japan and South Korea decreed progressive reforms and land redistributions in order to outflank communists.

In some cases, America really has underwritten most of the funding for international institutions, whether their purpose is to monitor ancient ruins (UNESCO) or inspect nuclear sites (IAEA). It hasn’t done so out of altruism. The investment has paid itself back many times over. These institutions have worked imperfectly, but they build goodwill and reduce risk. That’s good for the world in general, but it’s great for America.

It’s true that America’s role is expensive. In 2015, America spent more than the next seven nations combined on defense. Worried about this gap in the years after 9/11, some American officials and neoconservative ideologues complained that “Old Europe” should pay more for its defense. Like Trump, they argued that Europe has been able to reap an economic windfall because America shoulders so much of the NATO security umbrella.

At best, this analysis is a dangerous exaggeration; Europe could and probably should shoulder more of the cost, but the US investment in NATO is worthwhile for its own sake. At worst, by threatening NATO, the “free-rider” trope sets up America to shoot itself in the foot – shaking its security and breaking up a system with huge direct benefits to Americans.

Rather than a nation rooked by crafty foreigners, it makes more sense to see America at the center of a web of productive investments. Here’s how it works:

First, most of America’s defense spending functions as a massive, job creating subsidy for the U.S. defense industry. According to a Deloitte study, the aerospace and defense sector directly employed 1.2 million workers in 2014, and another 3.2 million indirectly. Obama’s 2017 budget calls for $619 billion in defense spending, which is a direct giveback to the American economy, and only $50 billion in foreign aid – and even that often ends up in American pockets through grants that benefit American farmers, aid organizations, and other US interest groups. The U.S. military, and the Veterans Administration, are an almost socialist paradise of equality, job security and full health care when compared to life for Americans not on the payroll of the Defense Department and its generously (even absurdly) remunerated contractors. The defense budget, by playing on America’s obsession with security rather than social welfare, allows Washington to pump a massive stimulus into the economy every year without triggering another Tea Party.

Second, America’s steering role in numerous regions — NATO, Latin America, and the Arabian peninsula — gives it leverage to call the shots on matters of great important to American security and the bottom line. For all the friction with Saudi Arabia, for instance, the Gulf monarchy has propped up the American economy with massive Treasury bill purchases, and by adjusting oil production at America’s request to cushion the effect of policy priorities like the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Third, and most importantly, if you listen the biggest critics of the new world order, what you’ll hear is that it’s rigged – in America’s favor. America’s “global cop” role means that shipping lanes, free trade agreements, oil exploration deals, ad hoc military coalitions, and so on are maintained to the benefit of the U.S. government or U.S. corporations. The truth is that America puts its thumb on the scale to tilt the world’s not-entirely free markets to America’s benefit. Nobody would be more thrilled for America to pull back than its economic rivals, like China.

Perhaps that’s why analysts in the business of predicting world affairs don’t think Trump is going to abandon America’s “world policeman” portfolio once he looks at the bottom line.

“Trump wants to be seen as projecting strength around the world and intends to expand spending on U.S. defense,” wrote Eurasia group’s Ian Bremmer shortly after the election. He might be more abrasive, and he might pressure some of America’s bottom-tier allies. But if he wants to be a strongman, he’ll have to keep America’s stick.

Obama, too, apparently thinks Trump will like being the world’s policeman even more than he’ll like being Putin’s friend. “There is no weakening of resolve when it comes to America’s commitment to maintaining a strong and robust NATO relationship and a recognition that those alliances aren’t just good for Europe, they’re good for the United States. And they’re vital for the world,” outgoing President Obama said on his valedictory trip to Europe, claiming confidence that Trump shared that view of global alliances.

Within Trumpworld, there’s no question a real rift exists on this question. Isolationist-nationalist America-firsters, like Steve Bannon, really do want to see America pull back, and downplay the costs in the interests of their ideological goals. Profit-driven internationalists like Rex Tillerson, however, are intimately acquainted with the benefits of keeping an American hand in global affairs.

Trump might like the sound of handing in America’s resignation as global cop. His voters might like it even more. But if pulling back makes America poorer and more vulnerable, the costs will land squarely on Trump.

When it comes time to choose between the two camps, Trump might find himself torn between an isolationist camp he connects with emotionally and an internationalist one that will — in the gross calculus of profits and power — be more of a winner. That’s a feeble rationale for a sound international order, but it might be the best one going in the age of Trump.