Hariri’s Unnerving Interview

Lebanon’s Prime Minister Saad al-Hariri, who has resigned, is seen during Future television interview, in a coffee shop in Beirut, Lebanon November 12, 2017. Photo: REUTERS/Jamal Saidi

[Published in The Atlantic.]

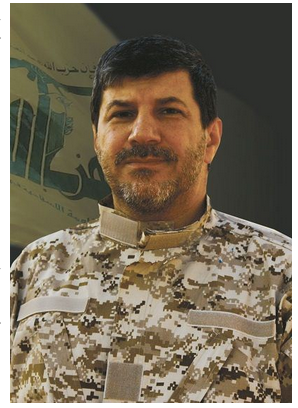

In the Middle East, the parlor game of the moment is guessing whether Saad Hariri, Lebanon’s prime minister—or is it ex-prime minister?—is literally, or only figuratively, a prisoner of his Saudi patrons. In a stiff interview from an undisclosed location in Riyadh on Sunday, Hariri did little to allay concerns that he’s being held hostage by a foreign power that is now writing his speeches and seeking to use him to ignite a regional war. He insisted he was “free,” and would soon return to Lebanon. He said he wanted calm to prevail in any dispute with Hezbollah, the most influential party serving in his country’s government.

Since Hariri was summoned to Saudi Arabia last week and more or less disappeared from public life as a free head of state, rumors have swirled about his fate. On November 4, he delivered a stilted, forced-sounding resignation speech from Riyadh. Michael Aoun, Lebanon’s president, refused to accept the resignation, and Hezbollah—the target of the vituperative rhetoric in Hariri’s speech—deftly chose to stand above the fray, absolving Hariri of words that Hezbollah (and many others) believe were written by Hariri’s Saudi captors.

The bizarre quality of all this aside, the underlying matter is deadly serious. Saudi Arabia has embarked on another exponential escalation, one that may well sacrifice Lebanon as part of its reckless bid to confront Iran.

Foreign influence seeps through Middle Eastern politics, nowhere more endemically than Lebanon. Spies, militias, and heads of state, issue political directives and oversee military battles. Foreign powers have played malignant, pivotal roles in every conflict zone, from Iraq and Syria to Yemen and Libya. Lebanon, sadly, could come next. Even by the low standards of recent history, the saga of this past week beggars the imagination, unfolding with the imperial flair of colonial times—but with all the short-sighted recklessness that has characterized the missteps of the region’s declining powers.

Saudi Arabia, it seems, is bent on exacting a price from its rival Iran for its recent string of foreign-policy triumphs. Israel and the United States appear ready to strike a belligerent pose, one that leaders in the three countries, according to some reports, hope will contain Iran’s expansionism and produce a new alignment connecting President Donald Trump, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and Benjamin Netanyahu.

The problems with this approach are legion—most notably, it simply cannot work. Iran’s strength gives it a deterrence ability that makes preemptive war an even greater folly than it was a decade ago. No military barrage can “erase” Hezbollah, as some Israel war planners imagine; no “rollback,” as dreamed up by advisers to Trump and Mohamed bin Salman, can shift the strategic alliance connecting Iran with Iraq, Syria, and much of Lebanon.

Saudi Arabia, as the morbid joke circulating Beirut would have it, is ready to fight Iran to the last Lebanese. But the joke only gets it half right—the new war reportedly being contemplated wouldn’t actually hurt Iran. Instead, it would renew Hezbollah’s legitimacy and extend its strategic reach even if it caused untold suffering for countless Lebanese. Just as important, a new war might be biblical in its fire and fury, as the bombast of recent Israeli presentations suggests. But that fire and fury would point in many directions. Iran’s friends wouldn’t be the only ones to be singed.

Saudi Arabia’s moves have gotten plenty of attention in the days since Mohamed bin Salman rounded up his remaining rivals, supposedly as part of an anti-corruption campaign. Hariri was caught in the Saudi dragnet around the same time. It seemed puzzling at first: For years, Saudi Arabia had been angry with Hariri and his Future Movement, its client in Lebanon, for sharing power with Hezbollah rather than going to war with it. Riyadh was clearly displeased with Hariri’s pragmatic positions. He had learned the hard way, after several bruising political battles and a brief street battle in May 2008, that Hezbollah’s side was the stronger one. Rather than fuel a futile internecine struggle, Hariri (like the rest of Lebanon’s warlords) opted for precarious coexistence.

Once it became clear that Hariri could do nothing to prevent Hezbollah’s decisive intervention in the Syrian civil war, Saudi Arabia cut off funding for Hariri, bankrupting his family’s billion-dollar Saudi construction empire. It also ended its financial support for the Lebanese army, cultivating the impression that it considered Lebanon lost to the Iranians and Hezbollah.

Now, Saudi Arabia has steamed back into the Lebanese theater with a vengeance. It dismisses Hezbollah as nothing but an Iranian proxy, and, in the words uttered by Hariri in his resignation speech, wants to “cut off the hands that are reaching for it.” In what must be an intentional move, it has destroyed Hariri as a viable ally, reducing him to a weak appendage of his sponsors, unable to move without the kingdom’s permission. Mohamed bin Salman won’t even let him resign on his home soil. If Hariri really were free to come and go, as he insisted so woodenly in his Sunday night interview, then he would already be in Beirut. Even his close allies have trouble believing that threats against his life prevent him from coming home, and the Internal Security Forces, considered loyal to Hariri, denied knowledge of any assassination plot.

The Saudis have fanned the flames of war, seemingly in ignorance of the fact that Iran can only be countered through long-term strategic alliances, the building of capable local proxies and allies, and a wider regional alliance built on shared interests, values, and short-term goals. What Saudi Arabia seems to prefer is a military response to a strategic shift, an approach made worse by its gross misread of reality. In Yemen, the Saudis insisted on treating the Houthi rebels as Iranian tools rather than as an indigenous force, initiating a doomed war of eradication. The horrific result has implicated Saudi Arabia and its allies, including the United States, in an array of war crimes against the Yemenis.

Hariri has clearly tried to balance between two masters: his Saudi bosses, who insist that he confront Hezbollah, and his own political interest in a stable Lebanon. On Sunday night, he appeared uncomfortable. At times, he and his interviewer, from his own television station, looked to handlers off camera. The exchange ended abruptly, after Hariri implied that he might take back his resignation and negotiate with Hezbollah, seemingly veering from the hardline Saudi script. “I am not against Hezbollah as a political party, but that doesn’t mean we allow it to destroy Lebanon,” he said. His resignation does nothing to thwart Hezbollah’s power; if anything, a vacuum benefits Hezbollah, which doesn’t need the Lebanese state to bolster its power or legitimacy.

One theory is that the Saudis removed Hariri to pave their way for an attack on Lebanon. Without the cover of a coalition government, the warmongering argument goes, Israel would be able to launch an attack, with the pretext of Hezbollah’s expanded armaments and operations in areas such as the Golan Heights and the Qalamoun Mountains from which they can challenge Israel. Supposedly, according to some analysts and politicians who have met with regional leaders, there’s a plan to punish Iran and cut Hezbollah down to size. Israel would lead the way with full support from Saudi Arabia and the United States.

Short of seeking actual war, Saudi Arabia has, at a minimum, backed a campaign to fuel the idea that war is always possible. But such a war between Saudi Arabia and Iran would upend still more lives in a part of the world where the recently displaced number in the millions, the dead in the hundreds of thousands, and where epidemics of disease and malnutrition strike with depressing regularity. Short of direct war, Riyadh’s machinations will likely produce a destabilizing proxy war.

If Hariri were a savvier politician, he could have used different words; he could have refused to resign, or insisted on doing so from Beirut. But he is an ineffective leader in eclipse, unable to deliver either as a sectarian demagogue or a bridge-building conciliator. Saudi Arabia’s plan to use him to strike against Iran will fail. Just look at how willfully it has misused and now destroyed its billion-dollar Lebanese asset. It’s a poor preview of things to come in the Saudi campaign against Iran.

Iran’s Edge

Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps in a military parade marking the 36th anniversary of Iraq’s 1980 invasion of Iran, in front of the shrine of late revolutionary founder Ayatollah Khomeini, just outside Tehran, on Sept. 21, 2016. AP PHOTO/EBRAHIM NOROOZI

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

The decision by President Trump to decertify the Iran deal and impose sanctions on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps marks the public debut of a campaign that’s been underway since the spring, when Trump ordered his national security team to find ways to “roll back” Iranian influence.

As we’re likely to see over the coming year, Iran has cultivated its own options to throw nails and bomblets in the path of any presumptive American juggernaut. It might be possible to roll back Iran’s reach in the Middle East, but not without painful costs, which can be visited on a web of American targets and allies located throughout Iran’s sphere of influence.

According to Middle East experts who have consulted privately for the administration on Iran policy, the president asked for ways to raise the price for Iran of its expansionist policy in the region — without exposing America to direct new threats. That might not be possible.

After a decade during which America tried to balance the regional contest between Iran and Saudi Arabia, with its deepening Shia-Sunni sectarian inflection, Trump has cast his lot with one side. When he placed his hands on a glowing orb in Saudi Arabia, he overtly endorsed an all-Sunni gathering whose primary purpose was to counter Iran in the region.

We’re about to witness a real-life test of an Iran policy that eschews diplomacy and embraces confrontation. Trump and his advisers have described their volte-face against Iran in terms of deterrence theory, which attempts to put a scientific gloss on how threats of war play out between two nuclear powers capable of mutually-assured destruction.

But it’s not deterrence theory that offers the best guess of what the coming escalation with Iran might look like, it’s the gritty modern historical record.

During America’s messy occupation of Iraq, militias trained and funded by Iran were able to pose the most sustained military challenge to US troops. Sophisticated bombs called “explosively-formed penetrators” were able kill Americans even in the US military’s best armored vehicles. US officials believed that Iran provided these weapons and the training to use them — but kept their hands off the operations so they wouldn’t provoke a direct conflict.

Late in his final term, in 2007, President George W. Bush slapped a foreign terrorist organization designation on the elite Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, but stopped short of designating the entire armed forces, a move which Iranian leaders have said they would consider an act of war. Around that same time, some American officials were musing publicly about preemptive military strikes on Tehran’s nuclear program.

Then, as now, Washington was exploring a wider escalation with Iran while also probing for ways to prick Iran in regional flashpoints. One apparent pushback saw American troops detain five Iranian employees at the consulate in the Iraqi city of Erbil.

In that heated context, a remarkable raid took place on January 20, 2007. Militiamen in American uniforms, driving a convoy of SUVs identical to those commonly used by US troops and contractors, sped into an American facility in Karbala. They were inside before guards noticed anything amiss. They spared the Iraqis on the base, targeting only Americans, and managed to kidnap five soldiers who were later killed by their captors.

Evidence later emerged connecting the attack to Iran; not conclusively enough to justify direct retaliation by the United States, but enough to leave another bruise, and another argument that America couldn’t tangle with Iran cost-free.

Officials and analysts around the Middle East have speculated for years about where Iran might begin striking back against American interests if the two nations came to blows.

The Karbala raid suggests what Iran is capable of. In recent statements, commanders of the IRGC have warned that American installations could be targeted anywhere within 1,250 miles of Iran’s borders — the range of Tehran’s conventional missiles.

But a direct strike would engulf Iran in a direct war with the United States in which it would be at a great disadvantage. History suggests that Iran’s leadership prefers indirect conflict, with all the advantages of asymmetric warfare and plausible deniability. And there are a plethora of American targets in the Middle East that are exposed to Iranian-linked malefactors who could strike with weapons much more basic, and less traceable, than a long-range missile.

Today there are more than 5,000 American troops stationed in Iraq. Meanwhile, Iran’s regional relationships have grown deeper and broader. Along with its long-time militia allies, including foreign groups whose members spent the 1980s and 1990s in exile in Iran, today there are tens of thousands of new militiamen actively trained and advised by Iran. They are part of the Popular Mobilization Forces created to fight the Islamic State, or ISIS. Many PMF units are directly under Iran’s control but fought hand in glove with the United States in the campaign against ISIS.

Today, some of those same PMF militia fighters are embroiled in a dangerous confrontation with Kurdish Peshmerga forces around Kirkuk.

A quick perusal of Iran’s reach and alliances lends credence to what longtime Iran watchers argued: Iran does best in a regional proxy war. According to this analysis, Iran has little incentive to break out to a nuclear weapon, or fire the long-range rockets it already has developed, while it has every incentive to magnify its ability to destabilize and threaten rivals with indirect attacks by groups it supports: acts of sabotage, terrorism, and proxy warfare. (Supporters of the Iran nuclear deal argued that Iran’s penchant for indirect warfare meant it was never likely to pose a nuclear threat even if it did acquire a weapon, while critics said it underscored the destabilizing danger of Iran’s unchecked spoiler tactics.)

Examples abound, from the campaign of hostage-taking in Beirut in 1980s (mostly conducted by Hezbollah, but clearly at Iran’s direction), to the creation of proxies in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq, to support for hyper-sectarian politics across the Levant and the Arabian peninsula. Sure, other regional powers like Saudi Arabia have used the same tactics, but to far less effect and usually not in direct opposition to US interests (at least when it comes to state-orchestrated violence; terrorist blowback and a permissive environment for terrorism are another matter entirely, and the reason why a sounder policy from Washington would entail containing Saudi Arabia as well as Iran.)

Status quo powers like the United States, Russia, and China, even when they are competing for influence, share a common interest in unified, effective state structures. They like to do deals (for oil, weapons, or other commodities) and build alliances with unitary governments that have a clear leader and functional institutions.

Iran, by contrast, has done well in the Middle East when its neighbors are too weak and fragmented to pose a threat. The Islamic Revolution almost collapsed during the war with Saddam Hussein in the 1980s. Iran’s leaders concluded that their best bet was to cultivate unstable, fragmented, and squabbling neighbors who couldn’t pose such a threat. Iran has mastered better than any other intervening power the tactics of jockeying for influence in a kaleidoscopic, unstable war zone with dozens of competing militias and power centers.

While other powers have struggled to maintain toeholds in shifting environments like Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, the security apparatus of Iran has built thriving spheres of influence; its operatives are comfortable working with multiple, even dozens, of proxies, warlords, and local allies. The Iranians are able to hedge their bets and extend their influence in these fragmented zones of authority not because they are evil geniuses, but because their goals are different and easier to achieve.

Furthermore, the Iranians have a home-court advantage – their stake in the Middle East can’t fluctuate like it does for faraway imperial powers. Tehran also has invested in a long game, without end. Many of its operatives spend their entire careers working in Iraq, Syria, or Lebanon; they speak fluent Arabic and build relationships over decades with their military, intelligence, and political counterparts.

They seek unimpeded military access to proxies, influence with governments, and access to markets — all goals easily achieved in a context of fraying state authority.

Needless to say, it’s easier to undermine and erode state institutions than to build them.

This skill set — honed in Lebanon since the early 1980s and then later in Syria and Iraq — translated easily to the war in Yemen that expanded two years ago. It most certainly will help Iran in a phase of renewed confrontation with Trump’s America.

Iran and Saudi Arabia double down on Cold War neither can win

Saudi Arabia’s execution of prominent Shiite Muslim cleric Nimr al-Nimr during a mass execution of 47 people has further ignited a regional rivalry between Iran and Riyadh. Photo: MOHAMMED AL-SHAIKH/AFP/GETTY

[Published in Newsweek.]

The recent tit-for-tat clashes across the Middle East have made the first days of 2016 seem a lot like 1979. That was the year Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini led Iran’s transformation from an autocratic state ruled by the Shah into the Islamic Republic. Violence wracked the region in the immediate aftermath of the changeover. Mobs overran embassies, and Sunni Arab governments swore to turn their backs on the new theocratic regime in Tehran. Oil-rich despots throughout the region poured money and weapons into proxy conflicts all over the Middle East, unleashing a wave of destabilizing, sectarian violence that eventually died down but never went away.

The event that turned back the clock and made an already roiling situation boil over took place on January 2, when Saudi Arabia killed a dissident Shiite cleric, Nimr al-Nimr, in a mass execution of 47 people. Iranian mobs attacked Saudi Arabia’s diplomatic missions in Tehran and Mashhad. A flurry of escalations followed: bombings in Yemen, diplomatic relations severed, promises of retaliation by both Riyadh and Tehran.

Although they’re an alarming throwback to 1979, these incidents are just the most recent round in a long, destructive struggle between two powers apparently set on pulling the entire region into a struggle between a Sunni bloc and a Shiite crescent. Both are seeking a winner-takes-all victory. “All the sectarian rhetoric is becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy for these regimes who love to play the sectarian card,” says Farea al-Muslimi, a Yemen analyst at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. “The Saudis feel betrayed, and now they feel like they must do something, even if it’s the wrong thing.”

The two oil-rich theocracies—one Shiite and one Sunni—are vying for regional dominance. The feud between Iran and Saudi Arabia has fueled sectarianism, resulted in an increase in the flow of weapons and funding to extremists, and spawned numerous militant movements.

Neither side shows any sign of backing down. Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, promised “divine justice” after al-Nimr was executed. Saudi Arabia’s monarchy, meanwhile, put out the word through allies that “enough is enough” and that it would no longer hesitate to stand up to Iran.

But even more of a threat to the region than this Iran vs. Saudi Arabia contest is the likelihood that the two countries are lashing out at each other not from positions of strength but of weakness—and in their efforts to dominate each other they could cause the entire region to fracture and spin out of control. The two autocracies appear set on ratcheting up their clash, consequences be damned. But it also seems clear that neither Iran nor Saudi Arabia can control the wars, proxy militias and ideological movements their conflict has unleashed. Even if Tehran and Riyadh calm down, the armed groups they have spawned could continue fighting throughout the region.

If there is a single event that sparked this flare-up, it was the 2015 Iranian nuclear deal, which saw Iran agree to dismantle its nuclear program in exchange for the lifting of sanctions. The agreement was clearly good for global security, but it also dramatically changed the region. Saudi Arabia, which views itself as the Sunni world’s banker, oil baron and spiritual chief, felt abandoned by its most important ally, the United States, widening a rift that opened in 2011 when Washington supported popular uprisings against Arab tyrants during the Arab Spring.

When the Obama administration was pursuing its nuclear accord with Iran, Saudi Arabia felt betrayed, and now the U.S. was preparing to help the Saudis’ biggest regional rival by lifting sanctions. At almost the same time, oil from fracking and other sources has made the U.S. a major oil state, no longer directly dependent on Middle Eastern—particularly Saudi—oil.

King Salman, Saudi Arabia’s new monarch, took an uncharacteristically confrontational approach with the U.S. His inner circle lobbied against the Iran deal, and in March—over strenuous American objections—Saudi Arabia launched a massive assault on Iranian-backed rebels in Yemen. By the time the nuclear deal was inked in July, the Saudis were dangerously close to a rupture with Washington.

Some Western diplomats said the Saudis’ decision to execute al-Nimr—when they knew full well it would antagonize Iran (and the U.S., among others)—seemed specifically designed to thwart the major Syrian peace conference scheduled for January 25 in Geneva. Peace talks without Saudi Arabia and Iran, powerful backers of opposing sides in the war, would be a waste of time.

Saudi Arabia’s bellicose maneuvers have strained its relationship with Washington. U.S. diplomats and security officials say they are angry about citizens of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries financially backing jihadis in Syria, Libya and elsewhere in the region.

But the Saudi royal family, if it is to survive, must keep the country’s powerful extremist Sunni (or Wahhabite) clerical establishment on its side. That means that the monarchy wants to persuade Washington that Saudi Arabia is a firm counterterrorism ally while demonstrating to its subjects at home that it will protect the conservative religious core of the Wahhabi sect.

The execution of the Shiite cleric was “local politics,” says one Arab analyst who works closely with the Saudi government and spoke on condition of anonymity because he didn’t want to anger officials. “They don’t want to lose more support to ISIS, so they need to show they can be more hard-line than ISIS. That’s why they killed Sheikh Nimr.”

The execution was also a way for Saudi Arabia to block what it sees as Iranian ascendance. After almost five years of stalemate in Syria, President Bashar al-Assad’s regime has been winning back territory, thanks to significant military support from Tehran and Moscow. Iraq, a Shiite-majority neighbor, has also become an Iranian ally. In Lebanon, the Iranian-backed Shiite militant group Hezbollah is stronger than ever, and the nuclear deal with the U.S. and other world powers will greatly boost Iran’s revenues and reintegrate the Islamic Republic into the global economy and the international community.

But a closer look suggests all is not so rosy for Iran. Abroad, it has lost much of the support and soft power it cultivated directly after its 1978-1979 revolution. In the mid-2000s, Iran’s so-called axis of resistance—an informal coalition of Iran, Syria, Hezbollah and the Sunni-dominated group Hamas—enjoyed widespread popularity among Sunni and Shiite Muslims.

Today, polls show that Iran’s popularity in an increasingly polarized region has evaporated. Like Saudi Arabia, with its backing of rebels in Syria and its military campaign to support the government in Yemen, Iran has overreached and become inextricably involved in wars that are unlikely to have an outright victor. Hezbollah openly took sides with the Assad regime and has lost its Pan-Arab luster.

And Iran, despite the considerable resources of its expeditionary Quds force and the fearsome reputation of its commander, General Qassem Soleimani, has been unable to guarantee the survival of the Syrian regime, in spite of the recent military successes of Assad’s forces and their allies. In Yemen, the side Iran supports, the Houthis, is steadily losing ground in the face of the Saudi-led assault.

“Iran and Saudi Arabia have managed to establish a mutually destructive cycle of conflict in which both sides are damaging their future regional position,” says Michael Hanna, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation and co-author of a recent article titled “The Limits of Iranian Power” in the journal Survival: Global Politics and Strategy.

“While most assume that Iran is much better positioned, it is much more isolated than is generally recognized,” says Hanna, who argues that Iran’s alliances are under extreme strain. “Its soft power in a majority Sunni Arab world has collapsed, and it is now limited to exercising hard power in sectarian conflicts.”

Whatever happens in this round of the Saudi-Iranian rivalry, things promise to get worse, not better. “The policies of the Saudi regime will have a domino effect, and they will be buried under the avalanche they have created,” said Iranian Revolutionary Guards Brigadier General Hossein Salami on January 7, according to Iran’s state-run Press TV. “If the Al-Saud regime does not correct this path, it will collapse in the near future.”

Both sides frame their competition more and more in absolutist, sectarian terms, and both sides have proved less and less able to manage the endless crises in the region. Iran and Saudi Arabia are doubling down on a war neither can win.

Managing the War in Yemen: Diplomatic Opportunities in the Mayhem

The war unfolding in Yemen has created a humanitarian and political catastrophe.1 Since Saudi Arabia intervened in Yemen’s civil war at the end of March, the conflict has spiraled into an open, multiplayer regional war that has killed more than 2,000 people. For long stretches, Yemen’s seaports have been blockaded, threatening the food supply of an estimated half of the population of 24 million. Meanwhile, the number of displaced has lurched upward to 1 million.2

The conflict in Yemen marks yet another unfortunate escalation in the region that will exacerbate security problems and political divisions. This time around, Arab governments and the United States should do everything they can to calm the conflict before it becomes another intractable killing field. Washington already recognized Yemen’s strategic importance and for years has targeted terrorist operatives there with drone strikes. Now, the United States and its allies have the opportunity to learn from recent missteps in the region and take advantage of the halting negotiations that opened recently in Genevabetween the warring parties.3

The next few months offer a narrow window to prioritize diplomacy over military action in a bid to shift worsening dynamics across the Middle East. Regional governments and multilateral organizations ought to take every conceivable diplomatic step available today, even in the face of likely failure or obstruction, to address the Yemen crisis. Otherwise, it could quickly turn into another Syria, an intractable, grinding conflict that destroys one nation, while implicating a raft of others in a conflict that has no good possible outcomes.

This brief will assess the interests of outside powers that are playing a significant role in the Yemeni civil war and try to identify points of entry for diplomacy and de-escalation, with the long-term goal of creating new forums for dialogue between Saudi Arabia, Iran and other governments. The riskier internationalized phase of the war in Yemen is only three months old, and it has dragged in many key players in the region, including the United States. Military action is unlikely to resolve the conflict there, but an effective political process—which depends on international support—might reverse a dangerous escalation.

Download this Issue Brief as a PDF

A Complex Conflict—and Its Consequences

In Yemen today, two amorphous and loosely allied coalitions are battling each other, with one roughly grouped behind Saudi Arabia and the other behind Iran. The dynamics and identities of these groupings are fluid and malleable. And as with the three other hot wars currently being fought in the Arab world—in Syria, Iraq, and Libya—the Yemen conflict is marked by a considerable degree of external interference. The stakes are high for the foreign interventionists: Saudi Arabia and its allies believe their stance in Yemen denotes a line of departure in a belated, but essential, campaign to check Iran’s influence, while Iran sees Yemen as yet another battleground on which it can pressure its regional rivals while maintaining a plausibly deniable degree of involvement. 4,5

Foreign support has emboldened militias on both sides of the conflict, and almost all sides are already pursuing military options.6 While Yemen’s competing factions fight, Al Qaeda inthe Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) has been entirely spared foreign military strikes and is enjoying renewed latitude to operate.7

The Yemen crisis poses many dangers. The most obvious lie in Yemen itself, where starvation could become endemic and an avoidable escalation of civil war could lead to a mass humanitarian tragedy. Security blowback is an equally intense strategic concern. AQAP has been one of the most active groups plotting international terrorist attacks, including against the United States. The disruption of U.S.-allied counterterrorism efforts in Yemen, and now the collapse of any central state authority, directly empower AQAP and increase the threat to the United States.8 The coalition led by the Houthis, a group with a distinct tribal and sectarian identity inside Yemen, which is currently supported by Iran and by deposed president Ali Abdullah Saleh, has grievances mostly rooted in the local sharing of power and resources.9 It is impossible to assess whether Iran views the interests of the Houthi alliance as close to Iran’s core interests, or whether it tactically views the Houthis as another chit to deploy in a region-wide strategy that seeks to maximize Iranian footholds that can be used to project power or can be traded away in negotiations.

The Yemen war also has clear ramifications for its direct neighbors. Rightly or wrongly,Saudi Arabia always has considered Yemen a core national security interest,10 often trying to manage Yemen’s affairs as if it were another Saudi province. The tightly intertwined business elites of the two countries11 and a hard-to-police shared border12 make it hard for Riyadh to ignore developments to the south. Since March of this year, Saudi Arabia, acting out of genuine fear of Iran’s expanding influence, has embarked on a coalition air war that has no discernible end game.13 While Saudi perceptions might be exaggerated, developments in Yemen are indeed linked to Iranian efforts to deepen their partnership with the Houthis. Critics paint the Saudi intervention as impulsive and slipshod and point out that King Salman could not persuade long-time Saudi beneficiaries such as Pakistan and Egypt to contribute troops for a potential ground operation.14 But Saudi Arabia’s concerns are real, and they cannot be wished away by governments that do not share them. Any broader strategic rapprochement in the region will require a clear understanding of the concerns of the Arabian Peninsula monarchies and measures to restore their sense of security and confidence.

Doubtless, the humanitarian emergency in Yemen will strain an already bad security climate. But it also provides an opportunity to engage the full array of problematic and recalcitrant regional governments with an eye toward assuaging their insecurities and creating diplomatic avenues through which they can explore more enduring fixes to regional problems. The current historical moment, while high risk, offers an opportunity for outside powers to deploy diplomatic influence in a concerted and sustained manner. It is worthwhile in its own right to try to limit the war in Yemen and to calm tensions between the complex web of combatants. But equally importantly, any well-designed initiative—even one that fails—could amount to a major accomplishment if it began to fill the void of regional mechanisms through which rival states can directly negotiate.

What would such an initiative look like, and why should there be any hope that it will work any better than the plethora of failed diplomatic initiatives around the Syrian civil war?

Formulating a Response

The cascade of events that escalated the civil war in Yemen signals a repositioning by key regional powers. Indeed the conflict brings into sharp relief some of the perceived and actual interests at stake for key players, including the Sunni Arab monarchies in the Arabian Gulf, the rulers of Iran, and outside guarantors like Russia and the United States. But this volatile and vulnerable period has an upside: by laying bare some of the fears and ambitions of key regional actors, the turmoil invites governments with the potential for good offices to organize several different diplomatic initiatives. At worst, they will amount to a little more talk in a region that does not experience enough, at least between adversaries. At best, multilateral and bilateral diplomatic initiatives can serve as life-saving palliatives for the immediate catastrophe in Yemen and also potentially as vehicles to curtail the conflict and begin a long process (with admittedly long odds) of creating a nonmilitary forum to resolve regional tensions.

Absent a sharp change of direction soon, the war in Yemen risks following the same course as Syria’s: devolving into an unwinnable and destabilizing stalemate, shredding national well-being for Yemen and prestige for outsiders who thought they could determine the conflict’s course.15 Because the regional external stakeholders in the Yemen war are concurrently implicated in Syria’s, it is worth trying to persuade them to change course in Yemen before it is too late. Paradoxically, some of the same players that have been ineffective or malignant in Syria could play a positive role in calming tensions in Yemen, perhaps because their own prestige is not yet on the line. The United States, Russia, the United Arab Emirates and the United Nations are obvious candidates to serve as early diplomatic brokers.

Existing diplomatic outreach has reaped some benefits. The UN appointed a new envoy on April 25 and helped negotiate a humanitarian ceasefire in May.16 The United States government has met with both sides of the conflict inside Yemen, and it has been adept at simultaneously managing multiple aspects of the diplomatic crisis. The talks in Geneva that begin on June 14 hold some basic promise but fail to include all the necessary actors.17 A concerted diplomatic push could be catalyzed by comparatively level-headed players, such as the United Arab Emirates, the United States, and the United Nations, and could make use of problematic but potentially useful forums such as the Organization of the Islamic Conference, the Gulf Cooperation Council, and the Arab League. The aim would be to begin a diplomatic process that would include, even at a remove, both Saudi Arabia and Iran, and which would have at least a prospect of serving as an avenue to address the bedrock security concerns undermining regional security and driving the Yemen war. Any diplomatic effort to reduce tension between those two nations must take into account their stakes throughout the region.

Iran

Iran is enjoying a moment of expanding regional influence, but one that it perceives as under constant threat. It has made headway in negotiating a nuclear framework agreement with the United States and Europe, but it has suffered extensive economic isolation under sanctions.18 Iran has outsized influence over Iraq’s government, but that government has porous control over its own territory and can barely maintain a fiction of national sovereignty over Kurdish and Sunni areas.

The Syrian regime has been a tight client of Iran, but at great cost to Tehran—perhaps as much as $60 billion in financial support and a hard-to-measure, but deep, commitment of military and political resources.19 Iran and its partner, Hezbollah, have kept the Syrian regime afloat, but they have found the Syrian sponsees brittle and unresponsive to the political requests of their paymasters, who have unsuccessfully counseled the regime to experiment with political conciliation to end the civil war. Meanwhile, the ISIS proto-state in Iraq and Syria entails a direct and violent challenge to Iranian designs, interests, and legitimacy in the Arab and Islamic world.

Engaging Iran on the issue of Yemen while all these factors are in play could yield multiple benefits. Internal competition inside Iran between the military-revolutionary guard complex and the clerical-merchant elite raises the possibility of exploitable differences of opinion within the Iranian government. Yemen talks might also be an avenue to gauge whether Iran has changed its position on other issues in the wake of the nuclear framework accord negotiations. It is also possible that Iran does not see Yemen as a core interest and might even desire a de-escalation there, even as it appears to ramp up its military commitment in Syria. All these factors suggest that, while Iran seems ascendant, its concerns and internal dynamics open the possibility for a wider spectrum of diplomatic engagement.20

Yemen talks allow for a narrow focus, but all the players are aware of the wider context. Iran and the United States are on the verge of a major shift as a result of the nuclear negotiations. Arab governments are nervous that Washington will tilt away from them and toward Iran. It is important to manage the exaggerated fears and expectations; any U.S. shift on Iran is likely to be incremental, and a diplomatic process can help calm insecurities that can produce destabilizing violence like the war in Yemen. There is alo an economic component to discussions with Iran that could provide significant leverage to increase security. If and when sanctions on Iran are loosened, the Western sponsors of the nuclear talks could wisely direct a sizable share of their proceeds from the resulting economic boom to the very same Sunni Arab countries most worried about Iran. If Arabian Peninsula economies profit from Iran’s opening—through trade, the funneling of Western investment via Arab entrepôts in the Gulf, or even through direct investments of their own—the long-term prospects for peace and stability increase. 21

The mechanics of such an economic windfall might be complicated. New private investment in Iran will not be driven by the diplomatic priorities of Western governments. But it is very possible that some of the biggest new, or renewed, foreign economic partnerships with Iran will come from companies that are traditional partners of government policy, like U.S. defense contractors and engineering conglomerates or European chemical and automobile manufacturers.22 The goal for diplomats would be to encourage investors to allow some of the post-sanctions Iran bonanza to pass through the Arab world, perhaps through creative partnerships between Western corporations and financial and technical partners in the Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman. An imperfect but useful analogy can be found in Iraq’s Kurdish north, where the Kurdistan Regional Government and its predecessors opened the borders to massive, profitable Turkish investments. The Turkish stake (and profits) in Kurdish Iraq have created enduring shared interests and reduced long-running tensions, despite real political disagreements. 23

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia in March used the Arab League to launch its entrance into the Yemen war, and it has tried to rally pan-Arab support against what it describes as foreign Iranian aggression.24 The rhetoric of the March summit had overtones of Sunni Arab Nationalist grievance against a Shia and Persian-inflected conspiracy.25 There were also overt notes of triumphalist return of the established conservative political order after a period of experimentation ushered in by the period of popular uprisings.

Any sense of a restoration, or a new Pax Arabicus, is premature, however, and will quickly fade. Saudi Arabia already is seeing the difficulty of imposing a clean solution on Yemen and is reportedly considering a partition of the country.26 Riyadh is also well aware of the intractability of the Syria conflict, and it has begun to see the drawbacks of the ally it enlisted by helping install Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as Egypt’s ruler.

King Salman is experienced, but he is new in his role as king and is heavily reliant on his approximately thirty-year-old son to shape policy.27 Transition periods allow for flux and also for adaptation. If Salman can be persuaded that it will protect Saudi’s core security interests, he could probably accept some shifts in policy on Yemen, or perhaps even on the wars in Syria, Iraq, and Libya.

The new administration in Saudi Arabia is experimenting with a new approach to foreign policy. It is a ripe moment to establish new mechanisms with Saudi Arabia because the kingdom’s top officials, and its policy orientations, are changing. King Salman has openly reconsidered the kingdom’s outright hostility toward the Muslim Brotherhood;28 he has taken a step back from his predecessor’s tight embrace of the dictator Saudi helped install in Egypt;29 he has taken new initiative to invigorate Sunni rebels in Syria;30 and he hassuggested in a range of leaks and public statements that Riyadh is willing to strike out on a policy course independent from Washington.31 However, that last position might be bluster, since Saudi and the United States have close, intertwined policy interests, including limiting the reach of Al Qaeda, maintaining a free flow of oil to global energy markets, and trying to check Iranian regional hegemony. Saudi Arabia depends on the U.S. security umbrella, and the United States depends on Saudi’s willingness to adjust the amount of oil it pumps to maintain world supplies in the face of geopolitical disruptions caused by events like the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the embargo on Iranian oil, and the sporadic disruption of Libyan oil supplies since 2011. There is not likely to be a divorce, but Saudi Arabia is looking for supplementary partners and has made clear that it feels the U.S. is inadequately committed to Arab regional security.32 Regional discussions might offer an opportunity for Washington to emphasize its long-term investments in the region and its commitment to stability.

A (Limited) U.S. Role

Somewhat by accident, the United States has found itself in a position where it can negotiate along a complimentary line of diplomatic inducements. And Washington has taken this opportunity with more alacrity than it has at other junctures since the Arab uprisings began.

While finalizing the nuclear framework agreement with Iran, the United States simultaneously signed on to an explicitly anti-Iran war in Yemen33 and withheld military support in Iraq until Iran-backed militias took a backseat in the battle for Tikrit.34 The United States showed that it could keep its eyes on many parts of the map at the same time and that it would play hardball with Iran on other issues, even while making compromises in the interest of limiting its nuclear program.

The United States can do the same with its allies as well. It can assist the Saudi campaign in Yemen in the short-term, while counseling the development of an exit strategy. It can also volunteer to coordinate complementary, if not identical, positions for Egypt, Iran, and the Muslim Brotherhood. Riyadh is unlikely to embrace a U.S.-Iran nuclear deal, but it might effectively shelf its opposition in exchange for a symbolic increase in U.S. security guarantees for the Arabian Peninsula.

Creative diplomacy can explore other pathways to reassure allies and convince them to accept otherwise unpalatable tradeoffs. An example of the kind of innovative, small-scale problem solving that could evolve in the framework of regional talks involves nuclear power. Arab states are dissatisfied that they lack nuclear programs while Israel maintains an undeclared nuclear arsenal and Iran appears to be on the verge of winning international approval for a robust research program that will leave it only a few steps away from a weapons program. The United States could look for ways to alleviate this dissatisfaction, for example by taking the lead in sponsoring nuclear power plants in the Gulf and its Arab allies, such as Egypt and Jordan. U.S. companies have already been making inroads—Westinghouse is part of the coalition that is currently building nuclear reactors in the United Arab Emirates. Official backing behind such a strategy, however, would also signal commitment and perhaps act as a salve for local energy problems and symbolic compensation for a perceived technology and support gap. Nuclear power is just one example of a secondary area that could be channeled in the Yemen talks to prompt progress on a wider scale.

Enabling Regional Dialogue

At the moment, there is no forum in which Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Saudi Arabia regularly sit together to air regional concerns. Nor is there a meaningful forum where the full range of regional actors who actually affect developments on the ground regularly meet. If regional dialogue is to have a place in cooling down Yemen—as well as the other wars in the Arab world at the moment—such a forum would have to include the Arab States, Iran, Turkey, and probably Russia, France, the United Kingdom, the United States, the European Union, and the United Nations. The path to such a structure is long and would probably have to begin piecemeal, but a genuine Yemen contact group would be a fine place to start.

The crisis in Yemen is in early enough stages to enjoy the potential for amelioration. Furthermore, all the key players have in front of them Libya and Syria, vivid examples of what happens in an entrenched war zone in which the combatants and sponsors refuse to engage in diplomacy. The first step would require the United States and Russia to set an example and show that, even while confronting one another over the crisis in Ukraine, they can agree to support a dialogue, even a tense one, over a second issue, in this case Yemen. The United Nations talks in Geneva could be expanded upon, or even moved to a neutral location closer to the region like Nairobi, Athens, or Istanbul. The first agenda could focus simply on humanitarian relief and access, but all players would have to be invited, including Iran.

Hopes for a diplomatic initiative on Yemen should be muted. The habits of bluster, confrontation, and proxy warfare are deeply engrained, and normalized relations have eluded key Middle East actors for nearly half a century. The United States has contributed to this culture by its support for an often moribund Israel-Palestine negotiating framework and by regularly backing diplomatic initiatives, like the Geneva process on Syria, that are meaningless from the start because they exclude key actors in the conflict.

In the event of a strong push from international and regional diplomats, key actors, including Saudi Arabia and Iran, might respond with recalcitrance or even outright rejectionism. But if the initial agenda focuses on humanitarian matters and battlefield access for neutral parties, and possibly on communications channels for battlefield deconfliction that could prove useful to all parties, it will be easier over time to persuade Tehran and Riyadh to take part.

The key is to attract the full range of players. The initial agenda can revolve around comparatively easy matters, such as opening ports to more regular food deliveries, increasing battlefield access for internationally recognized humanitarian aid workers, and the creation of some kind of emergency communications channel to reduce the risk of an unintentional international escalation of the war. Little is lost if the entire process amounts to a failed diplomatic initiative. Any resulting political embarrassment for supporting governments can be managed. The conflict in Yemen, however, is too important to simply be allowed to unfold at the mercies of regional powers acting in the grip of uncertainty and perceived threat. And a new diplomatic approach carries the possibility, however slim, of creating a useful new forum where adversaries can talk to each other in a conflict-ridden region that sorely lacks one.

Notes

1. Stephanie Nebehay, “Yemen faces humanitarian catastrophe without vital supplies: Red Cross,” Reuters, May 27, 2015,http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/05/27/us-yemen-security-redcross-idUSKBN0OC1W720150527.

2. See UNOCHA Yemen page for overview of latest statistics on the humanitarian crisis in Yemen: “Yemen,” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, June 2015, http://www.unocha.org/yemen, accessed June 9, 2015.

3. “In Geneva, Ban says international community has ‘obligation to act’ for Yemen peace,” UN News Centre, June 15, 2015,http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=51153#.VX7_IflVhBd.

4. Peter Salisbury, “Yemen and the ‘Saudi-Iranian Cold War,’” Chatham House, February 18, 2015.http://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/field/field_document/20150218YemenIranSaudi.pdf.

5. Mohsen Milani, “Iran’s Game in Yemen: Why Iran Is Not to Blame for the Civil War,” Foreign Affairs, April 19, 2015, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/iran/2015-04-19/irans-game-yemen.

6. Some photographs of the conflict have been collected on The Atlantic website: Alan Taylor, “The Saudi Arabia-Yemen War of 2015,” The Atlantic, May 7, 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2015/05/the-saudi-arabia-yemen-war-of-2015/392687/.

7. Hugh Naylor, “Quietly, al-Qaeda offshoots grow in Yemen and Syria,” Washington Post, June 4, 2015,http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/quietly-al-qaeda-offshoots-expand-in-yemen-and-syria/2015/06/04/9575a240-0873-11e5-951e-8e15090d64ae_story.html.

8. Azmet Khan, “Understanding Yemen’s Al-Qaeda Threat,” PBS NewsHour, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/foreign-affairs-defense/al-qaeda-in-yemen/understanding-yemens-al-qaeda-threat/.

9. Khaled Fattah, “Yemen: Sectarianism and he Politics of Regime Survival,” in Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf, ed. Lawrence G. Potter (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 223.

10. Ginny Hill and Gerd Nonneman, “Yemen, Saudi Arabic and the Gulf States: Elite Politics, Street Protests and Regional Diplomacy” Chatham House Briefing Paper,https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/public/Research/Middle%20East/0511yemen_gulfbp.pdf.

11. Peter Salisbury, “Yemen’s Economy: Oil, Imports and Elites,” Chatham House Middle East and North Africa Paper 2011/02, 9–12.

12. Anthony H, Cordesman, “Saudi Arabia’s Changing Strategic Dynamics” in Saudi Arabic: Security in A Troubled Region (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2009), 31–32.

13. Bruce Riedel, “Why Saudi Arabia’s Yemen War is Not Producing Victory” Al-Monitor, March 26, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/05/yemen-war-escalates-stakes-raise-saudi-princes.html.

14. Mark Perry, “US Generals: Saudi Intervention in Yemen a ‘Bad Idea,’” Al Jazeera, April 17, 2015,http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/4/17/us-generals-think-saudi-strikes-in-yemen-a-bad-idea.html;Kenneth Pollack, “The Dangers of the Arab Intervention in Yemen,” Markaz: Middle East Politics & Policy, March 26, 2015,http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/markaz/posts/2015/03/26-pollack-saudi-air-strikes-yemen; and Frederic Wehrey, “Into the Maelstrom: The Saudi-Led Misadventure in Yemen,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 26, 2015, http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=59500.

15. Peter Salisbury, “Is Yemen Becoming the Next Syria?” Foreign Policy, March 6, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/03/06/is-yemen-becoming-the-next-syria/.

16. “Secretary-General Appoints Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed of Mauritania as His Special Envoy for Yemen,” UN announcement,http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sga1563.doc.htm.

17. Economist editorial offers minimal expectations for the June 14 “consultations”: “No end in sight,” The Economist, June 13, 2015, http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21654077-start-peace-talks-raises-little-hope-fighting-yemen-will?fsrc=rss%7Cmea.Humanitarians call for a permanent ceasefire: “Aid agencies: Permanent Yemen ceasefire needed now to save millions,” International Rescue Committee, June 11, 2015, http://www.rescue.org/press-releases/aid-agencies-permanent-yemen-ceasefire-needed-now-save-millions-24975.

18. US State Department page on Iran sanctions: “Iran Sanctions,” U.S. Department of State,http://www.state.gov/e/eb/tfs/spi/iran/index.htm, accessed June 15, 2015.

19. Eli Lake, “Iran Spends Billions to Prop Up Assad,” Bloomberg View, June 09, 2015.http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-06-09/iran-spends-billions-to-prop-up-assad/.

20. Thomas Juneau, “Iran’s Failed Foreign Policy: Dealing from a Position of Weakness,” Middle East Institute, May 01, 2015.http://www.mei.edu/content/article/iran%E2%80%99s-failed-foreign-policy-dealing-position-weakness.

21. Andrew Torchia, “Billions for Grabs if Nuclear Deal Opens Iran’s Economy,” Reuters, April 05, 2015.http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/04/03/iran-nuclear-economy-idUSL6N0X003P20150403.

22. Martin Hesse, Susanne Koelbl and Michael Sauga, “An Eye to Iran: European Businesses Prepare for Life after Sanctions,”Der Spiegel, May 18, 2015. http://www.spiegel.de/international/business/european-business-prepare-for-lifting-of-iran-sanctions-a-1034240.html and Jeremy Kahn, “Iran Lures Investors Seeing Nuclear Deal Ending Sanctions”, Bloomberg, August 17, 2014.http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-08-17/iran-lures-investors-seeing-nuclear-deal-ending-sanctions.

23. PKK guerilla fighters have never given up their base of operations in Iraqi Kurdistan and have apparently organized attacks inside Turkey from their base in the KRG. But Turkey has exhibited patience and understanding with the KRG, not holding them responsible for the militants on their soil, perhaps because of the thriving economic relationship that the KRG has invited. See Denise Natali, “Turkey’s Kurdish Client-State,” Al-Monitor, November 14, 2014. http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/11/turkey-krg-client-state.html# and Soner Cagaptay, Christina Bache Fidan and Ege Cansu Sacikara, “Turkey and the KRG: An Undeclared Economic Commonwealth,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy Policywatch No. 2387, March 16, 2015 http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/turkey-and-the-krg-an-undeclared-economic-commonwealth.

24. James Stavridis, “The Arab NATO,” Foreign Policy, April 09, 2015. http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/04/09/the-arab-nato-saudi-arabia-iraq-yemen-iran/.

25. Thanassis Cambanis, “Iran Is Winning the War for Dominance of the Middle East,” Foreign Policy, April 14, 2015.http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/04/14/yemen-iran-saudi-arabia-middle-east/.

26. David B. Ottaway, “Saudi Arabia’s Yemen War Unravels,” The National Interest, May 11, 2015.http://nationalinterest.org/feature/saudi-arabias-yemen-war-unravels-12853.

27. David D. Kirkpatrick, “Surprising Saudi Rises as a Prince Among Princes,” New York Times, June 06, 2015.http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/07/world/middleeast/surprising-saudi-rises-as-a-prince-among-princes.html?_r=0.

28. Yaroslav Trofimov, “Saudis Warn to Muslim Brotherhood, Seeking Unity in Yemen”, The Wall Street Journal, April 02, 2015.http://www.wsj.com/articles/saudis-warm-to-muslim-brotherhood-seeking-sunni-unity-on-yemen-1427967884.

29. H.A. Hellyer, “The New Saudi King, Egypt and the Muslim Brotherhood”, Al-Monitor, March 24, 2015. http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/03/saudi-arabia-new-egypt-muslim-brotherhood.html.

30. Erika Solomon and Simeon Kerr, “Syria’s Rebels Heartened by the Healing of Sunni Arab Rift” Financial Times, April 13, 2015. http://www.ft.com/intl/.cms/s/0/16a10034-df6c-11e4-b6da-00144feab7de.html#axzz3chSsxTTY.

31. Ray Takeyh, “The New Saudi Foreign Policy” Council on Foreign Relations Expert Brief, April 17, 2015.http://www.cfr.org/saudi-arabia/new-saudi-foreign-policy/p36456.

32. Jeremy Shapiro and Richard Sokolsky, “It’s Time to Stop Holding Saudi Arabia’s Hand” Foreign Policy, February 12, 2015http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/05/12/its-time-to-stop-holding-saudi-arabias-hand-gcc-summit-camp-david/.

33. Micah Zenko, “Make No Mistake—the United States is at War in Yemen,” Foreign Policy, March 30, 2015.http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/03/30/make-no-mistake-the-united-states-is-at-war-in-yemen-saudi-arabia-iran/.

34. Rod Nordland and Helene Cooper, “US Airstrikes on ISIS in Tikrit Prompt Boycott by Shiite Fighters,” New York Times, March 27, 2015,. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/27/world/middleeast/iraq-us-air-raids-islamic-state-isis.html.

DOWNLOADS

Iran vs. Saudi: Two repressive blocs face off

Photo Credit: Mohammed Huwais / Stringer

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

By Thanassis Cambanis

BEIRUT — The war in Yemen and the breakthrough nuclear agreement between Iran and the United States have sent the already frenzied Middle East analysis machine into meltdown mode. These developments come fast on the heels of almost too many changes to keep track of: the Iraqi government’s capture of the city of Tikrit, rebel gains in northern and southern Syria, and mass-casualty terrorist attacks in Tunis and Sanaa.

This drumbeat of headlines, however, should not distract us from the larger meaning of events in the Middle East. We are witnessing a struggle for regional dominance between two loose and shifting coalitions — one roughly grouped around Saudi Arabia and one around Iran. Despite the sectarian hue of the coalitions, Sunni-Shiite enmity is not the best explanation for today’s regional war. This is a naked struggle for power: Neither of these coalitions has fixed membership or a monolithic ideology, and neither has any commitment whatsoever to the bedrock issues that would promote good governance in the region.

This is, in some ways, an updated version of the vast and bloody struggle for hegemony that shook the Arab world in the 1950s and 1960s. In that era, a coalition of reactionary monarchs, led by Saudi Arabia, did battle with a coalition of Arab nationalist military dictators, led by Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser. Just like in that past era, every single major player today is opposed to genuine reform and popular sovereignty.

Today’s ascendant regimes are all reactionary survivors — and sworn enemies — of the Arab Spring. The Iranians mercilessly crushed the Green Revolution in 2009, and have invested heavily in authoritarian partners in Iraq and Syria, paramilitary group such as Hezbollah, and non-democratic movements in Bahrain and Yemen. Iran’s leaders are theocrats, but they are savvy and pragmatic geopolitical worker bees: They have backed Sunni Islamists and Christians, while even some of their close Shiite partners — like Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, an Alawite, and the Zaidi Houthis in Yemen — belong to heterodox sects and don’t share their views on religious rule.

On the other side of the struggle are the Arab monarchs from the Gulf, run by the same families that brought us the Yemeni war of the 1960s. They have extended their writ through generous payoffs and occasional violence, like the Saudi-led invasion of Bahrain in 2011, which saved the minority Sunni royal family from being overrun by the island kingdom’s disenfranchised Shiite majority.

This Saudi-led alliance is Sunni-flavored, but it would be incorrect to see it as monolithically sectarian.

This Saudi-led alliance is Sunni-flavored, but it would be incorrect to see it as monolithically sectarian. Not long ago, in fact, Saudi Arabia underwrote the same Zaydis it is now bombing in Yemen. The current coalition relies for populist credibility on Egypt, whose governing class is dominated by secular, anti-Islamist military officers. It enjoys dalliances in various conflict theaters like Syria and the Palestinian territories with Muslim Brothers and jihadis. It has drawn extensively on help from the United States — and on occasion from its supposedly sworn enemy, Israel.

Perhaps the best glimpse of the Saudi-led alliance’s goals came when Kuwaiti emir Sabah al-Sabah addressed the Arab League at the end of March, in the meeting that inaugurated the war in Yemen.

“A four-year phase of chaos and instability, which some called the Arab Spring, shook our region’s security and eroded our stability,” the emir thundered. The uprisings, he said, encouraged “delusional thinking” about reshaping the region — perhaps a reference to Iran’s ambitions of regional influence, perhaps a reference to the ambitions of Arab reformers to limit the influence of the repressive states propped up by the Gulf monarchies. To the emir, the only outcome of uprisings was “a sharp setback in growth and noticeable delay in our progress and development.”

This is the crux of the regional fight underway: the old order, or a new one that would transform the balance of power — while changing little else about the way the Middle East is governed. The Saudi bloc wants to turn back the clock to the status quo ante that existed before the uprisings. The Iranian bloc wants to permanently alter the region’s balance of power. Both factions are run by opaque, secretive, repressive, and violent leaders. Neither side is interested in popular accountability, better governance, or the rights of citizens.

For all the doubts about Saudi Arabia’s capacity to craft and execute complex policy, the kingdom has cobbled together a formidable coalition. It quickly signed up most of its clients and partners for the air campaign, including Morocco, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Sudan, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates. The United States supported the war, despite its reservations. Of the kingdom’s close allies, only Pakistan has so far resisted pressure to join the fight.

In just the last year, we’ve seen at least two major volte-face. Riyadh helped engineer a regime change in Egypt, ushering President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to power. After experimenting with quasi-democracy and a Muslim Brotherhood presidency that defied the powerful Gulf monarchies, Cairo is now governed by a military dictator who walks firmly in lockstep with Riyadh — even promising to dispatch ground troops to a war in Yemen of which he would have probably preferred to steer clear. Qatar, the unbelievably rich emirate that has long cultivated an independent foreign policy, also found itself strong-armed by Saudi Arabia and finally caved. Its emir abdicated in favor of his son, a 34-year-old political novice, and today Doha is reading from Saudi Arabia’s song sheet.

Both examples show that this is not a monolithic bloc bound by uniform ideas of authoritarian rule or Sunni supremacy. Instead, it is a messy realpolitik coalition hammered together by shared interests — and at times by bribes and blackmail. Its members don’t agree on everything: Saudi Arabia hates Russia, in part because Moscow backs Iran and Syria. Egypt loves Saudi Arabia because Riyadh keeps its economy afloat — but it also loves Russia, because it can play off military aid from Vladimir Putin against that from the United States. In public, Sisi praises the Gulf leaders — but in leaked private recordings, he dismisses them as oil bumpkins who can be bilked of their money by more dynamic Arab nations. Qatar no longer openly defies Saudi Arabia, but it still supports Muslim Brothers and jihadis in Syria to the extent it can, and in opposition to Saudi preferences.

Since Saudi Arabia’s gloves came off in Yemen,

Sunnis across the region have expressed a kind of fatalistic relief: At last someone is doing something to confront Iranian influence.

Sunnis across the region have expressed a kind of fatalistic relief: At last someone is doing something to confront Iranian influence. But Tehran has extended its influence carefully, hedging its bets by supporting multiple groups in every conflict zone and always maintaining a degree of remove — if their investments fail, it will have not lost a war in which it was a declared combatant. This blueprint has served Iran well during 30-plus years of intervention in Lebanon and Iraq, and four years of orchestrating major combat in Syria. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has entered the Yemen war directly, and therefore has no cover. It will own the civilian casualties, and inevitably — when the war has no clear and easy outcome — it will own a failure.

History is not on Riyadh’s side in this campaign. Regional wars tend not to go well for invaders; just think of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait or the last Yemen war in the 1960s. The U.S. invasion of Iraq should also offer a cautionary lesson: Many people at the time, including some Iraqis, felt that some major action was better than the status quo, that toppling Saddam Hussein would at the least get a hairy situation unstuck. They were soon disabused of that notion, as Iraq spiraled into chaos.

America should take particular care in this conflict. It has built deep alliances with Saudi Arabia, and it has been far too hesitant to reinvent its dysfunctional relationship with Egypt in the post-Mubarak era. It should act as a brake on Saudi Arabia’s outsized expectations in Yemen, and it should exact a price for any support it gives the war there. Any campaign in Yemen should strengthen, rather than undermine, counterterrorism efforts there, and the United States should share its military know-how in exchange for Saudi cooperation on the Iran deal.

Sure, it’s bizarre to see the U.S. military working with Iran to battle the Islamic State in Iraq, while working against Tehran in Yemen. It’s also refreshing. This isn’t a homily; it’s foreign policy. It’s encouraging to see the United States operating around the edges of a complex, multiparty conflict and finding ways to advance American interests. Its next challenge will be finding new ways to simultaneously pressure rivals like Iran and recalcitrant allies like Saudi Arabia.

But to a large extent, the United States is a sideshow: The main event is the regional struggle for influence between the Iran and Saudi blocs. One need only look at the two major events this spring — the Iran nuclear deal and the capture of Tikrit with the help of Tehran’s military advisors — to get a sense of who’s winning. America’s preferred side has bumbled impulsively from crisis to crisis, buying or strong-arming support and launching military adventures that are likely to produce inconclusive results. Iran’s side, meanwhile, has crafted tight state-to-state relations with Syria and its onetime enemy Iraq, and has deepened its influence in Afghanistan, Lebanon, Bahrain, and Yemen. Despite the theocratic dogma of Iran’s Shiite ayatollahs, the regime in Tehran has managed to position itself as the regional champion of pluralism and minorities, against a Saudi grouping whose philosophy has drifted dangerously close to the nihilism of al Qaeda and the Islamic State.

Unless Saudi Arabia and its allies can learn a new, more durable style of power projection, their costly feints will only buy short-term gains. The kingdom might manage to bomb the Houthis back to their corner of Yemen, and its Syrian clients may seize some more towns and cities from Assad, but the long-term trend points in Iran’s favor.

Foreign policy wins Obama still can pull off

JACQUELYN MARTIN/AP;

GLOBE STAFF PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.

LAST MONTH, in a pre-Christmas surprise, the White House announced a major foreign policy breakthrough on a front that almost nobody was watching: Cuba and the United States were ending nearly a half century of hostility, after secret negotiations authorized by the president and undertaken with help from the pope. Lately, America’s zigzagging on the grinding war in Syria and Iraq has attracted the most attention, but President Obama has punctuated his six years in power with a series of foreign policy flourishes, among them ending the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; launching an international military intervention in Libya; and a “reset” with Russia, which ultimately failed.

Time is running short. Obama has only two more years in office, and an oppositional Congress that will likely block any major domestic policy initiatives. But the president’s opening with Cuba raises a question. What other foreign-policy rabbits might this lame-duck president try to pull out of his hat?

Obama often talks about the arc of his history and his legacy. And we know from history that presidents in the sunset of their terms often turn their focus to foreign policy, where they have a freer hand. The presidential drift abroad has been even more pronounced in administrations that face an opposition Congress and limited support for any ambitious domestic agenda items.

Despite keeping his promises to end two wars and to reestablish America’s power to persuade, not just coerce, Obama has drawn some scorn as a foreign policy president. Poobahs across the spectrum from right to left have derided him for not having a policy (drifting on Syria, passively responding to the Arab Spring), for naively pursuing diplomacy (the reset with Russia, the pivot to Asia), for adopting his predecessor’s militarism (the surge in Afghanistan, the war on ISIS).

But, free from any future elections, the president may finally be at liberty to engineer bigger symbolic moves, like the recent rapprochement with Cuba. He can even try for politically unpopular policy realignments that would ultimately benefit his successor.

So what bold gambits might Obama reach for in his final two years? We’re talking here about unlikely developments, but ones that, with a push from a willing White House, could actually happen. Here’s a look at what might be on Obama’s wish list, and his real chances of grabbing any of these wonky Holy Grails.

A stand on torture

IN ITS WAR ON TERROR, America adopted a number of tactics that its leaders used to call un-American. Some of them appear here to stay, like remote-control bombing runs by robot planes (known by the anodyne moniker “drone strikes”), which have killed more than 2,400 people and have become the most common way Obama pursues suspected militants in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen.

But other tactics have lingered long after the White House has concluded they are counterproductive: most notably the use of torture, and the indefinite detention of enemies without charge or trial in the limbo prison at Guantanamo Bay. President George W. Bush, toward the end of his term, backtracked on both policies, quietly roping in the use of torture and exploring ways to shut down Gitmo. Obama has taken a more assertive moral stance on the issue, perhaps because he realized that America’s treatment of detainees delivered a propaganda boon to its enemies—and increased the risk of similar mistreatment for American detainees. But though he ended torture, he hasn’t settled the political debate, nor has he managed to close Guantanamo Bay.

This is one problem that Obama could resolve by fiat, if he were willing to deal with the inevitable political yelps. He could close Guantanamo Bay overnight, sending dangerous detainees to face trial in the United States, shipping others to allied states like Saudi Arabia, and releasing the rest (many of whom have spent more than a decade incarcerated). To those who would accuse him of putting America at risk by not detaining accused terrorists without charge forever, Obama could point to the US Constitution and shrug his shoulders. As for torture, some believe the best move would be to follow the South African model of a truth commission that airs all the grisly details, while granting immunity from prosecution to those who testify. Of course, critics of torture would decry the amnesty, and supporters would decry the release of narrative details.

Harvard political scientist Stephen Walt says to forget the truth commission. The simplest way for Obama to end one of the most contentious debates in America, he argues, is with a set of sweeping pardons for all those involved in torture. That could include officials from Bush on down, as well as leakers like Chelsea Manning. In an e-mail, Walt said such a move would be a “game changer,” although one with odds so long that he put it in the category of “foreign policy black swans.” “I regard it as very, very unlikely, but it would be a huge step,” he said.

Presidential pardons could make clear that torture and extrajudicial detention were illegal mistakes, while simultaneously freeing whistle-blowers and closing the books on the whole affair. Obama could even wait until after the 2016 presidential election has been decided, altogether eliminating political risk.

A détente with North Korea

EPA/KCNA ; GLOBE STAFF PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

NORTH KOREA entered the news recently because of its alleged role in the Sony hack over the silly film “The Interview.” But the hermit kingdom isn’t a problem because of its leader Kim Jong-un’s absurd cult of personality. No, North Korea poses a problem because it’s a belligerent, opaque, hyper-militarized state that stands outside the international system and is armed with serious rockets, nuclear warheads, and a powerful military.

One fraught area remains the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. About 30,000 American personnel are deployed there, and North Korea routinely provokes deadly clashes to remind the world of its resolve.

If Obama could finally end the Korean war—officially just in a cease-fire since 1953—he would resolve the most dangerous flashpoint in Asia and perhaps the world. Kim Jong-un, like his father and grandfather, has an almost mythic status among villainous world leaders. Millions have suffered in North Korea’s prison camps, and the militarized state maintains a hysterical level of propaganda that makes it stand out even among other “rogue” states. Even China, long the dynasty’s primary backer, has begun to express irritation with North Korean’s volatility.

But all this creates an opportunity, according to veteran Korea watchers. “There’s an opportunity, oddly enough,” says Barbara Demick, author of “Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea.” “It would require a bold gesture on somebody’s part.”

Kim Jong-un, third in the family dynasty, has lived abroad and appears more open-minded than his father, Demick says. More importantly, despite the anti-American rhetoric, North Korea might want to end its comparatively young feud with the United States, which dates only to the 1950s, to better protect itself from the local threat from its millennial rival China.

Earlier efforts at reconciliation in the early 1990s foundered and collapsed after Kim Jong-il cheated on an agreement to freeze his nuclear weapons program. Demick and other experts are more hopeful that his son will be more interested in negotiating. Three years after taking over, Kim Jong-un seems to have consolidated power. He has relaxed some control over private trade, and he executed a senior member of his own regime who was considered China’s man in Pyongyang, asserting himself over rivals within his family and government.

“Unlike his father, Kim Jong-un doesn’t seem to want to spend his whole life as the head of a pariah state,” Demick says.

It’s quite difficult to imagine North Korea doing an about face and becoming a friendly US ally in Asia, but surprising things have happened. Vietnam, just a few decades after its horrifying war with the United States, is now as warm to Washington as it is to Beijing. Obama could try to end one of the world’s longest lingering hot wars by forging a peace treaty with Pyongyang.

A grand bargain with Iran

AMERICA’S RELATIONSHIP with Iran never recovered from the trauma of the US embassy takeover and hostage crisis of 1980. Iran, flush with oil cash and the messianic fervor of Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolution, has been at the center of regional events ever since. Iran has been perhaps the most influential force in the Arab world, helping to form Hezbollah, prop up the Assad dictatorship in Syria, and foiling America’s plans in Iraq.

Of late, attention has focused on negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program, but that’s arguably not the most problematic aspect of Iran’s power in the region. A regional proxy war between two Islamic theocracies awash in petrodollars—Shia Iran and Sunni Iraq—has contaminated the entire Arab world. Resolving Iran’s major grievances and reintegrating it into the regional security architecture would reduce tensions in several ongoing hot wars and dramatically reduce risks across the board.