Everybody’s an Islamist Now

The case that a political term has outlived its usefulness

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

To watch the Arab world’s political transformation over the past year has been, in part, to track the inexorable rise of Islamism. Islamist groups—that is, parties favoring a more religious society—are dominating elections. Secular politicians and thinkers in the Arab world complain about the “Islamicization” of public life; scholars study the sociology of Islamist movements, while theologians pick apart the ideological dimensions of Islamism. This March, the US Institute for Peace published a collection of essays surveying the recent changes in the Arab world, entitled “The Islamists Are Coming: Who They Really Are.”

From all this, you might assume that “Islamism” is the most important term to understand in world politics right now. In fact, the Islamist ascendancy is making it increasingly meaningless.

In Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, the most important factions are led overwhelmingly by religious politicians—all of them “Islamist” in the conventional sense, and many in sharp disagreement with one another over the most basic practical questions of how to govern. Explicitly secular groups are an exception, and where they have any traction at all they represent a fragmented minority. As electoral democracy makes its impact felt on the Arab world for the first time in history, it is becoming clear that it is the Islamist parties that are charting the future course of the Arab world.

As they do, “Islamist” is quickly becoming a term as broadly applicable—and as useless—as “Judeo-Christian” in American and European politics. If important distinctions are emerging within Islamism, that suggests that the lifespan of “Islamist” as a useful term is almost at an end—that we’ve reached the moment when it’s time to craft a new language to talk about Arab politics, one that looks beyond “Islamist” to the meaningful differences among groups that would once have been lumped together under that banner.

Some thinkers already are looking for new terms that offer a more sophisticated way to talk about the changes set in motion by the Arab Spring. At stake is more than a label; it’s a better understanding of the political order emerging not just in the Middle East, but around the world.

THE TERM “ISLAMIST” came into common use in the 1980s to describe all those forces pushing societies in the Islamic world to be more religious. It was deployed by outsiders (and often by political rivals) to describe the revival of faith that flowered after the Arab world’s defeat in the 1967 war with Israel and subsequent reflective inward turn. Islamist preachers called for a renewal of piety and religious study; Islamist social service groups filled the gaps left by inept governments, organizing health care, education, and food rations for the poor. In the political realm, “Islamist” applied to both Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, which disavowed violence in its pursuit of a wealthier and more powerful Islamic middle class, and radical underground cells that were precursors to Al Qaeda.

What they had in common was that they saw a more religious leadership, and more explicitly Islamic society, as the antidote to the oppressive rule of secular strongmen such as Hafez al-Assad, Hosni Mubarak, and Saddam Hussein.

Over the years, the term “Islamist” continued to be a useful catchall to describe the range of groups that embraced religion as a source of political authority. So long as the Islamist camp was out of power, the one-size-fits-all nature of the term seemed of secondary importance.

But in today’s ferment, such a broad term is no longer so useful. Elections have shown that broad electoral majorities support Islamism in one flavor or another. The most critical matters in the Arab world—such as the design of new constitutional orders in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya—are now being hashed out among groups with competing interpretations of political Islam. In Egypt, the non-Islamic political forces are so shy about their desire to separate mosque from government that many eschew the term “secular,” requesting instead a “civil” state.

In Tunisia’s elections last fall, the Islamist Ennahda Party—an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood—swept to victory, but is having trouble dealing with its more doctrinaire Islamist allies to the right. In Libya, virtually every politician is a socially conservative Muslim. The country’s recent elections were won by a party whose leaders believe in Islamic law as a main reference point for legislation and support polygamy as prescribed by Islamic sharia law, but who also believe in a secular state—unlike their more Islamist rivals, who would like a direct application of sharia in drafting a new constitutional framework.

In Egypt, the two best-organized political groups since the fall of Mubarak have been the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi Noor Party—both “Islamist” in the broad sense, but dramatically different in nearly all practical respects. The Brotherhood has been around for 84 years, with a bourgeois leadership that supports liberal economics and preaches a gospel of success and education. The rival Salafi Noor Party, on the other hand, includes leaders who support a Saudi-style extremist view of Islam that holds the religious should live as much as possible in a pre-modern lifestyle, and that non-Muslims should live under a special Islamic dispensation for minorities. A third Islamist wing in Egypt includes the jihadists—the organization that assassinated President Anwar Sadat in 1981, which has officially renounced violence and has surfaced as a political party. (Its main agenda item is to advocate the release of “the blind sheikh,” Omar Abdel-Rahman imprisoned in the United States as the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.)

“ISLAMIST” MIGHT BE an accurate label for all these parties, but as a way to understand the real distinctions among them it’s becoming more a hindrance than a help. A useful new terminology will need to capture the fracture lines and substantive differences among Islamic ideologies.

In Egypt, for example, both the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis believe in the ultimate goal of a perfect society with full implementation of Islamic sharia. Yet most Brothers say that’s an abstract and unattainable aim, and in practice are willing to ignore many provisions of Islamic law—like those that would limit modern finance, or those that would outright ban alcohol—in the interest of prosperity and societal peace. The Salafis, by contrast, would shut down Egypt’s liquor industry and mixed-gender beaches, regardless of the consequences for tourism or the country’s Christian minority.

There’s a cleavage between Islamists who still believe in a secular definition of citizenship that doesn’t distinguish between Muslims and non-Muslims, and those who believe that citizenship should be defined by Islamic law, which in effect privileges Muslims. (Under Saudi Arabia’s strict brand of Islamist government, the practice of Christianity and Shiite Islam is actually illegal.) And there’s the matter of who would interpret religious law: Is it a personal matter, with each Muslim free to choose which cleric’s rulings to follow? Or should citizens be legally required to defer to doctrinaire Salafi clerics?

Many thinkers are trying to craft a new language for the emerging distinctions within Islamism. Issandr El Amrani, who edits The Arabist blog and has just started a new column for the news site Al-Monitor about Islamists in power, suggests we use the names of the organizations themselves to distinguish the competing trends: Ikhwani Islamists for the establishment Muslim Brothers and organizations that share its traditions and philosophy; Salafi Islamists for Salafis, whose name means “the predecessors” and refers to following in the path of the Prophet Mohammed’s original companions; and Wasati Islamists for the pluralistic democrats that broke away from the Brotherhood to form centrist parties in Egypt.

Gilles Kepel, the French political scientist who helped popularize the term “Islamist” in his writings on the Islamic revival in the 1980s, grew dissatisfied with its limits the more he learned about the diversity within the Islamist space. By the 1990s, he shifted to the more academic term “re-Islamification movements.” Today he suggests that it’s more helpful to look at the Islamist spectrum as coalescing around competing poles of “jihad,” those who seek to forcibly change the system and condemn those who don’t share those views, and “legalism,” those who would use instruments of sharia law to gradually shift it. But he’s still frustrated with the terminology’s ability to capture politics as they evolve. “I’ve tried to remain open-eyed,” he said.

It’s also helpful to look at what Islamists call themselves, but that only offers a perfunctory guide, since many Islamists consider religion so integral to their thinking that it doesn’t merit a name. Others might seek for domestic political reasons to downplay their religious aims. For example, Turkey’s ruling party, a coterie of veteran Islamists who adapted and subordinated their religious principles to their embrace of neoliberal economics, describes itself as a party of “values,” rather than of Islam. In Libya, the new government will be led by the personally conservative technocrat Mahmoud Jibril; though his party could be considered “Islamist” in the traditional sense, it’s often identified as secular in Western press reports, to distinguish it from its more religious rivals. Jibril himself prefers “moderate Islamic.”

The efforts to come up with a new language to talk about Islamic politics are just beginning, and are sure to evolve as competing movements sharpen their ideologies, and as the lofty rhetoric of religion meets the hard road of governing. The importance of moving beyond “Islamism” will only grow as these changes make themselves felt: What we call the “Islamic world” includes about a quarter of the world’s population, stretching from Muslim-majority nations in the Arab world, along with Turkey, Pakistan, and Indonesia, to sizable communities from China to the United States. For Islam, the current political moment could be likened to the aftermath of 1848 in Europe, when liberal democracy coalesced as an alternative to absolute monarchy. Only after that, once virtually every political movement was a “liberal” one, did it become important to distinguish between socialists and capitalists, libertarians and statists—the distinctions that have seemed essential ever since.

How Do Islamists Rule?

For the second year in a row, I’ve supervised a team of graduate students at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs in a comparative study of Islamist political movements and provincial governance. They’ll be presenting their findings this week at The Century Foundation. You can download a full copy of their report here (PDF).

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Religious political movements have been rising in popularity and power across the Islamic world for decades, amassing an ample record in local government. The Arab uprisings are only the most recent manifestation of this long-term trend. Yet there is little empirical study of the behavior of Islamist political parties, with prevailing assumptions never subjected to scrutiny. Conventional wisdom holds that ideology matters more to Islamist parties than to secular ones, and that once in power religious hardliners will moderate. Our study aims to clinically assess the performance of Islamist groups based on socio-economic data. It is difficult to compare Islamist parties across different time periods and national contexts, but we have looked for patterns and causal connections rather than hard-and-fast rules. We compared the ideologies and stated governing platform of the parties we studied to their political behavior and other outcomes measurable by data. Some general trends emerged:

Islamists invoke religion selectively. The level of Islamist rhetoric varied widely among the parties we studied. Those with an overtly religious discourse used it to gain political support and distinguish themselves from their secular counterparts, but applied religion only to some spheres of governance – usually gender equality and education, rather than issues like the economy or health.

Politics trumps ideology. Islamists respond to pressure from their constituents, displaying flexibility even on central points of doctrine if their political viability is at stake.

Context is controlling. Local structural concerns like economic crises or regime change trump ideology, pragmatically shaping the governing party’s agenda regardless of its stated ideology. The transitional narrative is particularly important in studying the rise of Islamists; many of these groups rose to power after decades of state suppression and underground activism.

Even when an Islamist party rises to power on a wave of religious rhetoric, we found across a variety of national narratives that ideology can be molded or subsumed by public opinion, local conditions, and pragmatic political constraints. We also found that Islamism is most useful as a predictor of political behavior on matters of social policy.

The Inevitable Rise of Egypt’s Islamists

A veiled woman casts her vote during the second day of the parliamentary run-off elections at a polling station in Cairo. Photo: Reuters

CAIRO, Egypt — Egypt’s liberals have been apoplectic over the early results from the recent elections here. Everybody expected the Islamists to do well and for the liberals to be at a disadvantage. But nobody — perhaps with the exception of the Salafis — expected the outcome to be as lopsided as it has been so far. Exceeding all predictions, Islamists seem to be winning about two-thirds of the vote. Even more surprising, the radical and inexperienced Salafists are winning about a quarter of all votes, while the more staid and conservative Muslim Brotherhood is polling at about 40 percent.

The saga is unfolding against a political backdrop of alarmism. One can almost hear the shrill cries echoing in unison from Cairo bar-hoppers and Washington analysts: “The Islamists are coming!” In short order, they fear, the Islamists will ban alcohol, blow up the sphinx, force burqas on women, and declare war on Israel.

Before we all worry too much, however, and before fundamentalists in Egypt start to crack the champagne (in their case perhaps literally, with crowbars), it’s worth taking a look at what’s really happening with Egypt’s Islamists.

Egypt is still not a democracy, so election results mean only a little; the key players in shaping the country remain the military, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the plutocrats. To a lesser degree, revolutionary youth, liberals, and former ruling party stakeholders will have some input. The new powers-that-be in Egypt and other Arab states who are trying to break the shackles of autocracy are likely to be more religious, socially conservative, and unfriendly to the rhetoric of the United States and Israel. That doesn’t mean they’ll be warmongers, or that they’ll refuse to work with Washington, or even Jerusalem, on areas of common interest.

Islamism has been on the rise throughout the Arab and Islamic world for nearly a century and will probably set the political tone going forward. The immediate future will feature a debate among competing interpretations of Islamic politics, rather than a struggle between religious and secular parties.

Islamist Surge?

WBUR’s Here & Now did a segment today on the success of Islamists in Tunisia’s elections, and the stated intent of Libya’s transitional rulers to base their new constitution on sharia (just like Iraq did during the American occupation!). Robin Young asked good questions, and was interested in probing the real debate within the Islamist political spectrum, to get past the all-too-frequent binary of scary Islamists versus nice secularists.

Her question:

The leader of Libya’s transitional council says Sharia Law will be the basis for the country’s new democracy; a moderate Islamist party is claiming victory in Tunisia’s elections; and, the Muslim Brotherhood is poised to do well whenever Egypt votes. Should the West be concerned or is this just the natural course of moving toward democracy in these Muslim countries?

My sense is that as political space opens up in Egypt, Syria, and other Arab countries, there will be an increased fracture between a “liberal” pole, made up of religious parties that advocate secular and civic governance, and a “conservative” pole, led by fundamentalists interested in theocratic governance. The cleavage won’t precisely map traditional differences between liberals and conservatives, and all parties to the debate will define themselves as religious Islamists. “Islamism” will cease to be a meaningful distinguishing label. Already, it’s hard to rely on the term when it applies equally to parties as different as Turkey’s AKP party, Tunisia’s Ennahda, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and Noor Party, Salafists in the Gulf, Hamas, Hezbollah, and so on.

Studying Political Islamism

Next spring I’ll be leading a group of graduate students at Columbia in a comparative analysis of how Islamist parties fare in provincial governance. The study will build on a project conducted by a team of SIPA students last year. Their full report is available here. I’m including the abstract below. The question continues to be of relevance as concerns — founded or not — about how Islamists will rule continue to drive American policy. For the second stage of the project we’re looking for suggestions to make the methodology as rigorous as possible.

* * *

How do Islamists rule?

An analysis of Islamist provincial governance

April 2011

Executive Summary

In recent years, increasing numbers of Islamist parties have risen to power through democratic elections. Though much has been written about Islamists, very little work has looked broadly at the question of how governing – in particular at the local or municipal level – affects these movements and their ideology.

Very little work has taken an empirical approach to measuring the performance of these movements as policymakers, providers of public services and enforcers of law and security. Most writing has focused on Hamas, to the exclusion of the other Islamist movements that have acquired a growing share of local (and sometimes national) power, especially in Iraq, Turkey, Pakistan, Jordan, Lebanon, the Gulf, and the Palestinian territories.

This report evaluates the success of two sub-national Islamist governments: the Muttahida Majilis-e-Amal (MMA) in the North Western Frontier Province (NWFP), Pakistan, which held power from 2002-2007, and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI, formerly SCIRI) and Al-Fadhila in Basra province, Iraq, which held power from 2005-2009. By examining data on indicators of social, economic and cultural development, the research team compared the performance of Islamists to that of their counterparts in each country.

While confirming some commonly held beliefs about Islamist parties in political power, such as their negative effect on gender equality, the report calls others into question. Our case studies challenge the oft-stated rubric that Islamists are stealth dictators who rule by coercion and disrespect democratic transitions of power. In many ways, we found that Islamist parties behave similarly to non-Islamist parties in positions of political power: they are opportunists who will stray from their campaign platforms if they find it in their institutional self-interest.

The MMA, which came to power as an anti-American, pro-sharia coalition, remained faithful to its revivalist rhetoric throughout its rule. The rights of women deteriorated in the NWFP, and education was increasingly Islamicized. In terms of security, the MMA was able to keep the peace, but mainly because it refused to aid the government’s pursuit of militants. The MMA was able to deliver public goods at a level comparable to its counterpart in Punjab, but in the end the coalition was racked with accusations of corruption, the various parties that constituted its core fractured along ideological and policy lines, and it overplayed its hand with a controversial bill which would have established sharia in the NWFP.

In Basra, many of the areas in which the Shia Islamist parties appeared to fare well were beyond their control. Literacy levels in Basra were some of the highest in the country under their rule, but education policy is run out of Baghdad through a national ministry. Similarly, the improvement in public health cannot be linked to any local policy because Basra was flooded with medical aid from various NGOs. An increase in gender-based violence can be attributed to Islamist policies, however, as can the deterioration of minority rights, as Sunni Muslims were targeted by Shia militias.

Focusing on the provincial level allowed for a greater degree of specificity in measurements and the ability to discern more competing views than can be witnessed on the national level in most quasi-democratic states. The experience of each party was unique, and the report does not make cross-national comparisons. However, both cases were located in conflict zones, which made it equally difficult to draw conclusions independent of exogenous factors.

Some of the report’s other conclusions and hypotheses include:

- Islamist rule in immediate post-conflict situations quickly yields to less divisive political factions (if subject to electoral politics).

- Islamist parties are not less corrupt than their secular counterparts.

- We witnessed moderation in both cases, but on different levels. While the MMA moderated their policies, the Iraqi parties merely moderated their rhetoric.

- Islamist parties at the local level can be constrained within federal frameworks.

The wave of protest and revolution currently rippling throughout the Middle East is likely to bring more of these groups into governing roles. Now that Islamists have proved their staying power, policymakers are looking for policy tools to moderate change. This report can help provide an understanding of what the transition to Islamist governance might mean.

The Shiny New Muslim Brotherhood

The Muslim Brothers hosted their grand coming-out party on Saturday night. Officially, the occasion marked the opening of their new headquarters, a seven-story monstrosity that looks like an egg-cream ziggurat on a breezy plateau above Islamic Cairo. Unofficially, the event was a declaration that the Brothers have arrived and will be kingmakers during Egypt’s season of political change.

“We’re not banned anymore,” exulted Mohsen Radi, who served a turn in parliament as a representative of a Delta town called Banha. “By the grace of freedom, by the grace of the revolution, we have regained our place.”

As symbols go, the building and its inaugural could not have been more potent. For decades, the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide operated out of a stuffy, dark, low-ceilinged apartment on the isle of Manial, in Cairo’s center. A team of state security men loitered out front. Entering visitors had to clamber over the pile of shoes in the hallway, between the elevator and the door. Senior officials would conduct interviews in the corner of the same room where the rest of the leadership was deliberating.

It was, to say the least, a no-frills operation, highlighting the Brotherhood’s ambiguous status as a legally prohibited but semi-tolerated organization.

Between 2005 and 2009, when the Brothers held 88 parliamentary seats, the organization opened a slightly more spacious parliamentary office nearby. State security forbade them from organizing any large public events, and even their annual Ramadan iftaar was cancelled. During functions there, the power often mysteriously cut out, with a frequency that the Brotherhood accepted as one of the more petty manifestations of state harassment.

Now, however, the Brotherhood is freely exercising its organizational muscle. Since Mubarak was run out of office, the Muslim Brotherhood has opened offices in every province. It is launching its own satellite television network. It has entered coalition talks with other groups, and has founded its own political party, called Freedom and Justice, which has a Christian vice president. At first, in an effort to comfort worried Christians and secularists, the Brotherhood said it would contest only 30 percent of the seats in parliament, and wouldn’t run a presidential candidate. Last week, it raised the ante, now saying it will compete for half the parliamentary districts.

With the opening of the new official headquarters in Moqattam, the transformation is complete. Bright lights illuminate the party logo in English and Arabic – a pair of green crossed swords.

About a hundred movement activists prayed outside before the official opening on Saturday night (the building’s been in use for weeks already). They chanted the Brotherhood motto in unison:

God is great.

The Prophet is our teacher.

The Koran is our constitution.

Jihad is our way.

Martyrdom is our goal.

Then they stormed into the building and emptied trays of fruit juice.

In a sign of the Brotherhood’s political heft, a parade of notables came to pay respects, including presidential front-runner and former Arab League chief Amr Moussa and a coterie of other secular politicians and judges.

In a rear lot behind the headquarters, more than a thousand supporters assembled in a dirt lot covered with carpets for the occasion. A band sang paeans to freedom, brotherhood, and the Brotherhood.

Khairat Shater, a millionaire and number-two official in the Brotherhood credited with being one of its most powerful fixers, grinned just beside the stage.

“Where do you think state security is now?” I asked. At the last Brotherhood function I attended, an iftaar in the parliamentary offices in August, the number of plainclothes intelligence officers hovering around the event equaled that of the Brotherhood officials inside.

“They haven’t gone home,” he said. “They’re around here somewhere.”

If one were keeping score, however, the Brotherhood would look to be ahead.

Rapture, Resistance, Revolution

In his review of A Privilege to Die for Global Post my friend the mystery writer (and veteran Middle East hand) Matt Beynon Rees calls attention to one the main endeavors of the book: to place front and center the regular Joes and Janes (or Ranis and Farahs) that have elevated Hezbollah into a perennial and expanding trend-setting militant movement.

In his review of A Privilege to Die for Global Post my friend the mystery writer (and veteran Middle East hand) Matt Beynon Rees calls attention to one the main endeavors of the book: to place front and center the regular Joes and Janes (or Ranis and Farahs) that have elevated Hezbollah into a perennial and expanding trend-setting militant movement.

Hezbollah’s rank-and-file, the footsoldiers and volunteers, aren’t always scheming against Israel or dreaming of perpetual war; they’re also strivers looking for better jobs, education for their kids, and a more honest relationship with God.

Because of its growth and success on the battlefield, the Party of God itself often takes on mythic status. Outsiders sometimes impute far greater cunning, skill and sophistication to Hezbollah than its occasionally clunky and authoritarian behavior merits.

Matt re-tells one of the more amusing encounters I had with Hezbollah while reporting the book:

Unsatisfied with one of his stories, Hezbollah officials denied his book the cooperation of the Party of God (“Hizb” means party in Arabic; “Allah” you probably heard of already.) He describes one party functionary telling him, “‘You can’t possibly write a book about Hezbollah without the party’s permission, right? You’ll have to move on to another project?’ Like many Hezbollah officials she overestimated the party’s ability to control or manipulate a foreigner like me and she thought the prospect of future access would tempt me to relinquish writing this book.”

Brotherhood boycott?

Parliamentary elections are coming up this fall in Egypt, probably in October or November. But the opposition and ruling National Democratic Party alike have their eyes on presidential succession, assuming that President Hosni Mubarak, who is ill and has ruled for 29 years, probably won’t run again in 2011. In that light, the parliamentary elections have become part of the broader political jockeying.

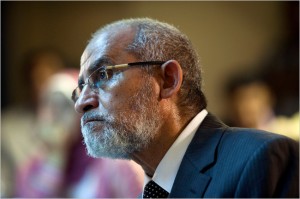

The Muslim Brotherhood commands by far and away the strongest street support among the opposition factions, but it’s a banned society whose parliamentary representatives are technically independents. Meanwhile, the secular opposition parties want to boycott the parliamentary elections to protest the ruling party’s heavy-handed manipulation of the voting process (since the last election, for instance, the government has cancelled the judiciary’s right to oversee polling stations). That’s the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide Mohammed Badie in the picture, getting yelled at by secular opposition leaders during an iftar.

The Brotherhood and the secular National Association for Change are circulating a petition calling on the government to amend the constitution and reform the voting process to allow free and fair elections. It’s a rare instance of the Islamist and secular opposition working together, but even in this arena they’re competing to show who’s stronger. The Brotherhood has collected nearly 700,000 signatures; the National Association for Change only 100,000. You can follow the dueling signature drives on the Brotherhood petition page and the NAC petition page.

You can also read more about the Brotherhood’s internal debate between seeking power and challenging it in my story today in The New York Times.

CAIRO — One by one, the guests at the Muslim Brotherhood’s annual Ramadan iftar banquet strode to the rostrum. A who’s who ofEgypt’s opposition began hectoring the Islamist group. The Brotherhood, they said, by far the most muscular and influential of Egypt’s dissident organizations, should withdraw from the coming parliamentary election that would most certainly be rigged by the authoritarian government.

“Why won’t you take the initiative?” shouted Karima El-Hefnawi, a secular activist and leader of the popular Kifaya protest movement. “Why won’t the Muslim Brotherhood boycott this farce?” The supreme guide of the Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie, sat uncomfortably a few feet to her right.

At the close of the evening, Mr. Badie was noncommittal. The Brotherhood, he said, in time would make up its mind: “Haste makes waste.”

The Muslim Brotherhood is engaged in a delicate dance. Despite all efforts to marginalize the Islamist organization by the United States and its close ally, the Egyptian government, it remains the most credible opposition group. Some of its members want the Brotherhood to fight the government head on, but the Islamist leadership has other goals: freedom to proselytize and organize in neighborhoods, and in the long term, a lifting of the official government ban on its activities.

With an end in sight to President Hosni Mubarak’s 29-year reign, the Brotherhood appears to be signaling its willingness to cut a deal with Mr. Mubarak’s potential successors by not overtly challenging the ruling party’s monopoly on power.

New York, Viewed from the Rest of the World

I’ve spent much of the last week covering the Park51 story from the Arab world. The entire affair has attracted far less attention in the Islamic world than one might expect. We put together a story that canvassed global reaction in today’s Times.

I’ve spent much of the last week covering the Park51 story from the Arab world. The entire affair has attracted far less attention in the Islamic world than one might expect. We put together a story that canvassed global reaction in today’s Times.

If the project’s organizers move the site, or cancel it altogether, I’d expect stronger opinions than we’ve seen so far. Same if there’s a major shift in public opinion, or a spate of violent attacks, or nastier rhetoric than we’ve seen so far.

For more than two decades, Abdelhamid Shaari has been lobbying a succession of governments in Milan for permission to build a mosque for his congregants — any mosque at all, in any location.

For now, he leads Friday Prayer in a stadium normally used for rock concerts. When sites were proposed for mosques in Padua and Bologna, Italy, a few years ago, opponents from the anti-immigrant Northern League paraded pigs around them. The projects were canceled.

In that light, the furor over the precise location of Park51, the proposed Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan, looks to Mr. Shaari like something to aspire to. “At least in America,” Mr. Shaari said, “there’s a debate.”

Across the world, the bruising struggle over an Islamic center near ground zero has elicited some unexpected reactions.

For many in Europe, where much more bitter struggles have taken place over bans on facial veils in France and minarets in Switzerland, America’s fight over Park51 seems small fry, essentially a zoning spat in a culture war.

But others, especially in countries with nothing similar to the constitutional separation of church and state, find it puzzling that there is any controversy at all. In most Muslim nations, the state not only determines where mosques are built, but what the clerics inside can say.

The one constant expressed, regardless of geography, is that even though many in the United States have framed the future of the community center as a pivotal referendum on the core issues of religion, tolerance and free speech, those outside its borders see the debate as a confirmation of their pre-existing feelings about the country, whether good or bad.

Ayatollah Fadlallah’s Legacy II (Updated)

David Kenner at foreignpolicy.com writes incisively about Fadlallah’s legacy as a religious leader who inspired Hezbollah and the Dawa Party but charted an independent course. As Kenner chronicles, the United States government misunderstood Fadlallah’s role, for years mistakenly considering him an operational leader of Hezbollah and trying to assassinate him in 1985.

There was an element of truth to the U.S. stance: Fadlallah was certainly no liberal, nor an ally to be recruited to advance U.S. security goals. However, even a quarter-century after that misguided assassination attempt, U.S. officials failed to appreciate the areas where their interests and Fadlallah’s overlapped, both in isolating Iran and reducing the appeal of fundamentalism within Lebanon. The United States always preferred blunt instruments and simple epithets — crude tools indeed for a complex man.

Unlike Hezbollah leaders, Fadlallah liked to meet with and debate those with whom he disagreed. A remarkable testament to this side of Fadlallah comes in this remembrance posted by the British Ambassador to Lebanon Frances Guy on her blog (where she regularly writes with surprising candor about things that other diplomats will hesitate to discuss as openly at background briefings).

When you visited him you could be sure of a real debate, a respectful argument and you knew you would leave his presence feeling a better person. That for me is the real effect of a true man of religion; leaving an impact on everyone he meets, no matter what their faith. … The world needs more men like him willing to reach out across faiths, acknowledging the reality of the modern world and daring to confront old constraints. May he rest in peace.

UPDATE

Fallout continues for public figures who praised Fadlallah after his death. First, CNN fired long-time Middle East editor Octavia Nasr after she posted a comment on Twitter expressing her sadness at the passing of a “Hezbollah giant” whom she “greatly respected.” (No matter that he wasn’t actually a Hezbollah figure, although he provided the religious justification for many of its tactics, include suicide bombings.) Now, the British Foreign Office has taken down Ambassador Guy’s blog post, “after mature consideration,” a spokesman told the Guardian newspaper.

Here’s the full text, of the post, as preserved by the Guardian.

One of the privileges of being a diplomat is the people you meet; great and small, passionate and furious. People in Lebanon like to ask me which politician I admire most. It is an unfair question, obviously, and many are seeking to make a political response of their own. I usually avoid answering by referring to those I enjoy meeting the most and those that impress me the most. Until yesterday my preferred answer was to refer to Sheikh Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah, head of the Shia clergy in Lebanon and much admired leader of many Shia muslims throughout the world. When you visited him you could be sure of a real debate, a respectful argument and you knew you would leave his presence feeling a better person. That for me is the real effect of a true man of religion; leaving an impact on everyone he meets, no matter what their faith. Sheikh Fadlallah passed away yesterday. Lebanon is a lesser place the day after, but his absence will be felt well beyond Lebanon’s shores. I remember well when I was nominated ambassador to Beirut, a Muslim acquaintance sought me out to tell me how lucky I was because I would get a chance to meet Sheikh Fadlallah. Truly he was right. If I was sad to hear the news I know other peoples’ lives will be truly blighted. The world needs more men like him willing to reach out across faiths, acknowledging the reality of the modern world and daring to confront old constraints. May he rest in peace.

Ayatollah Fadlallah’s Legacy

Lebanon’s Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah died on Sunday, snuffing out one of the most important voices for reform and restraint inside the milieu of Shia Islamism. As I wrote in Fadlallah’s obituary in The New York Times, the cleric had made his name as an advocate for the Shia awakening in the 1960s and 1970s, and then as a justifier of suicide bombings by Islamists.

Lebanon’s Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah died on Sunday, snuffing out one of the most important voices for reform and restraint inside the milieu of Shia Islamism. As I wrote in Fadlallah’s obituary in The New York Times, the cleric had made his name as an advocate for the Shia awakening in the 1960s and 1970s, and then as a justifier of suicide bombings by Islamists.

But he also won droves of supporters all across the Islamic world, including the non-Arab nations, because of his work on family law. He found that women should have an easier time winning divorces under Islamic law, and that they have the right to defend themselves from domestic violence. He directed vast sums of money to hospitals and charity groups, even setting up for-profit businesses like hotels and gas stations in under-served Shia areas and then funneling the proceeds to his social services network. Most of the Shia women I know, even those who sympathize with Hezbollah, considered Fadlallah their religious reference.

In January 2009, I interviewed him at his official headquarters around the corner from the mosque where he preached. He railed against the infighting in the Islamic world between Shia and Sunni Muslims, and between Muslims and Christians. Eventually, he said, America and Iran would arrive at a rapprochement, and so too would Israel and its neighbors (this last statement surprised me the most).

To a Westerner, it might be hard to distinguish among the different marjas, or “sources of emulation,” that devout Shia Muslims follow. They all believe that religious jurists have the right to issue fatwas on everything from marital relations to geopolitics. Beyond this common point, however, leaders like Fadlallah – and to a lesser extent, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani in Najaf – have provided a very different model than some of their counterparts in Qom, who advocate the Iranian model of wilayat al faqih, or direct rule by the jurisprudent (that is, the ayatollahs govern directly.)

Fadlallah believed the authority of the clerics depended on their authority among the people (and not solely from their divine link to God). He also believed that Islamic resistance had to retain its “humanism,” and therefore he condemned acts and movements that considered terrorist – like the Sept. 11 attacks, and the ongoing efforts of Al Qaeda. “We are not at war with the American nation,” he told me.

There aren’t many religious leaders whose views carry such weight and yet are willing to criticize their own followers and the movements that they inspire. Now there’s one fewer.

Nonviolence, Hamas Style

Civil disobedience has enjoyed a renaissance among Palestinians, most vividly with Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s call for a boycott against Israel rather than armed resistance. (Adam Horowitz and Philip Weiss describe the “Boycott Divestment Sanctions Movement” in this long essay in The Nation. Matt McAllester theorizes in The Daily Beast about why non-violence has failed to win Palestinian hearts.)

It remains possible that civic and political action will replace rockets and suicide bombings as the weapon of choice for Palestinian activists. So far, though, Hamas doesn’t seem too interested. In conversations I had with Hamas officials during a reporting trip to Gaza in January, I encountered glib jokes and incomprehension rather than any serious engagement with the idea of non-violence.

Hamas had suspended support for suicide bombings against Israeli civilians, but only, officials told me, because such attacks were failing to produce the desired effects – not because they were wrong, illegal or counter-productive.

“There are two paths: the path of Gandhi and the path of Al Qaeda,” Hamas parliamentarian and spokesman Salah al-Bardaweel told me. When I asked him which one Hamas would take he paused and then said: “Al Q-andhi!” He bellowed with laughter at his joke.

He did add more seriously that “there are many types of resistance,” and that Hamas promoted social, political, and cultural efforts along with its military wing. He pointed out that some groups have splintered from Hamas because they didn’t consider it militant enough. Historically, Bardaweel argued, Palestinian organizations that focused exclusively on politics and culture at the expense of armed struggle lost popular support. “We are a resistance group, but we can’t let military actions spoil our entire political plan,” he said.

At a seminar for junior Hamas officials at the House of Wisdom, a think tank chaired by Hamas’s deputy foreign minister, a group of men in their twenties and thirties scoffed when I asked if they could imagine Hamas adhering to the Geneva Conventions and using the tools of non-violent protest.

One, a mid-level Hamas bureaucrat named Ahmed al-Najjar, didn’t even understand the concept. “Non-violence?” he said to me. “What have we ever accomplished by the throwing stones?”

An American colleague described the tactics of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. As the American talked, Najjar leaned over to me and chuckled. “Non-violence in this part of the world is nonsense. What do you want? We should stand in front of the Israelis shouting ‘No, no occupation, go, go, occupation’? Non-violence is nothing. It does not work.”

Hezbollah’s New Museum

Lebanon’s Party of God opened a museum last month in the village of Mlita. I haven’t visited it yet, but I’ve seen lots of Hezbollah’s temporary annual exhibitions, which are similar but on a smaller scale. The Mlita Museum appears to raise Hezbollah’s culture (or cult) of resistance and martyrdom yet another level.

Lebanon’s Party of God opened a museum last month in the village of Mlita. I haven’t visited it yet, but I’ve seen lots of Hezbollah’s temporary annual exhibitions, which are similar but on a smaller scale. The Mlita Museum appears to raise Hezbollah’s culture (or cult) of resistance and martyrdom yet another level.

Don Duncan has just posted an excellent short video on The Wall Street Journal’s website. The four-minute clip seems to give a good sense of the Mlita museum, which opened on May 23, on the tenth anniversary of Israel’s withdrawal from the zone it occupied in southern Lebanon.

From inside a 600-foot-long tunnel, visitors can peer through glass at some of Hezbollah’s former underground hideouts. The fortifications were closely guarded secrets until recently, and key to some of Hezbollah’s recent operations, including its fight with Israel in a brief 2006 war along the southern border.

To manage the new museum and other planned sites, Hezbollah is creating its own museum department, adding to its other divisions, which include radio and TV stations.

“It shows that the resistance is more stable,” said Muhammad Kawtharani, director of Hezbollah’s arts foundation and a spokesman for the Mlita museum project. “You’re seeing a secret that is a secret no more.”

The sprawling permanent museum appears to mark another step on Hezbollah’s march to institutionalize its “Society of Islamic Resistance.” Hezbollah’s resourceful approach to guerilla warfare and propaganda have allowed it to nimbly adapt to changing circumstances, but as its power and reach have expanded, so too has its tendency to create static state-like structures.

The Los Angeles Times had a piece in May when the museum first opened, and Hezbollah put up a piece on Al Manar’s website extolling the Mlita complex. Al Manar’s language captures the flavor of Hezbollah public relations and propaganda:

“Mlita is full of sacrifices and memories that led to the achievement of the final victory,” Adnan Ibrahim Sammour, one of the engineers in charge of the project, told Al Manar … “This is the new Middle East, the real new Middle East that we have always dreamt of.” …

Mlita is a first step in the long struggle of writing down the Resistance’s history, a shining history that cannot be summarized with words, pictures, or even experiences…

Tariq Ramadan in the New World: The Atrophied Debate About Islam

Six years after the U.S. government banned him from the country, the celebrity Islamic scholar Tariq Ramadan landed in New York last week. The American government’s decision to reverse the ban marked a great victory for free speech advocates. Sadly, though, the conversation on stage suggested that a decade since the launch of the “Global War on Terror” (and despite the panelists’ best efforts) our public discourse is still distorted by the kind of thinking that begins with the question “Why do they hate us?” and unfolds with the false sense that the world’s billion-plus Muslims function as a monolithic and fanatical bloc.

Ramadan’s first public appearance, at Cooper Union in downtown Manhattan, had the kind of pomp and fanfare rarely associated with an intellectual event. People lined up around the block and paid $15, more than the price of a movie, to hear Ramadan and four other intellectuals brush every hot-button issue concerning the intersection of Islam and the West. Can Muslims loyally embrace Western secular governments? (Ramadan says of course.) Does Islam have a fundamental problem with women? (Historian Joan Wallach Scott says Westerners who care little for women’s equality in their own societies project their feminist discourse onto the Islamic world.)

Underlying the entire discussion was the general suspicion among some intellectuals on both the right and the left that Islam is fundamentally illiberal, and therefore incompatible with values like secular government, religious pluralism, and free speech. Tariq Ramadan – in part by choice, in part by happenstance – has been cast in the role of spokesman for “moderate Islamism.” He’s an Oxford professor; he’s religious; he’s the grandson of the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood; he’s a Swiss citizen of Egyptian origin; he’s a prolific writer; and he vigorously engages in the public sphere. At one time or another he’s confronted most questions about Muslims and their role in the West, and he’s left behind an ample public record to pick through. As a result, he’s become a favorite sounding board/punching bag/totem for people who argue about Islam and the West.

It’s only the beginning of his dialogue with the American public, and this first appearance was meant as much to celebrate the lawsuit that lifted Ramadan’s visa ban as it was to debut a serious discussion about Islamism in America and Europe. Despite the panel’s title – “Secularism, Islam and the West” (you can listen to the full audio here) – some questions seemed stuck in America’s first encounter with Islam after Sept. 11: Do you think it’s wrong to stone women? Does Islam countenance homosexuals? (Ramadan answered in the affirmative.)

The problem with such questions is that they presume first that Ramadan speaks as a religious authority, which he does not, and second that contemporary American political debates apply to the Islamic world, and should be used to frame some inquest into whether “Muslims,” as if they are a single entity, are good or bad. This “What went wrong?” ethos presumes that the fundamental matters of concern in the Islamic world, and among Muslim communities of the West, include gay rights, and whether women can drive or should be subjected to Taliban-style religious law. In fact, in the vast un-free zones of the Islamic world, people chafe at much more basic problems: the absence of any political rights, the lack of basic governance, stifled development, and in many places, widespread violence. Similarly, in the West, despite the outsized attention paid to extremists, the vast majority of Muslims agitate neither for religious rule nor for the cultural fundamentalism of the fanatics in Al Qaeda, the Taliban and the Shabab. When we want to engage the problem of violence and religious fanaticism meaningfully, we ought to do so with specificity. Do not ask “Why do they hate us?” Ask “What draws certain middle class youth away from politics and into the nihilistic violence of Al Qaeda?” or “Why do certain religious thinkers rule it’s okay to target civilians in a time of war?”

A more interesting debate began, when George Packer, a writer for The New Yorker, politely but with determination confronted Ramadan about his grandfather. What did Ramadan have to say, Packer asked, about his grandfather’s embrace of a Palestinian leader who had collaborated with the Nazis? Packer invited Ramadan to condemn the World War II-era mufti of Jerusalem for his Nazi sympathies, and also to go a step further and condemn his own grandfather, Hassan al-Banna, for embracing the mufti and ignoring the mufti’s work on behalf of the Nazis.

This question might seem obscure, but it raises a lot of the baggage with which the West often saddles Islamists and Palestinian activists – and which many of those same activists in turn have failed to confront and discard. Many Western liberals (and many Israelis, and many secular Muslims) believe that a profound stream of anti-Semitism and authoritarianism courses though Islamism. Those Islamists who engage in the debate reply that they oppose Israeli policy and not Jews, and that they would not govern in the dictatorial manner of Islamic movements like the Taliban or Al Qaeda. Supporters of a Palestinian state feel unfairly bludgeoned, held to a standard of historical perfection spared supporters of Israel: Why, they ask, do they have to account for their forebears’ behavior in the 1930s and 1940s while the world gives Israel a pass on the record of the Irgun and the Stern Gang? That question merits another essay, but in short, there’s plenty of public discussion about Israel’s (and the West’s) legacy of violence, and morality is not a zero-sum game. You don’t have to wait for your political rival to acknowledge right and wrong and confront a troubled past before asking yourself tough questions.

The problem comes in cases like that of the mufti of Jerusalem, or the waffling of Hassan al-Banna. Why don’t Islamist activists go out of their way to condemn their predecessors’ mistakes, or the excesses (or racism) of some of their peers? It’s fair enough that Ramadan wants to put the mufti’s actions in their historical context, just as many Palestinians and other Middle Easterners want to contextualize the acts of various militants in the ongoing war between Palestinians and Israel. But the quest for context need not prevent those advocates from decrying actions that are clearly wrong or misguided. The Palestinian case, presumably, does not rest on the infallibility of its leaders and its gunmen. Nor should proponents of a Palestinian state fear they would jeopardize their case if they were to condemn support for the Nazis, or for that matter, the targeting and killing of civilians. There are plenty of Palestinian, Islamist, and, for that matter, Israeli, constituencies that roundly condemn historical errors and criminal conduct by their fellow partisans; in the case of activist Islamism, however, such arguments are rarely heard from the leadership.

In Ramadan’s case, he’s neither a political leader nor religious jurist. The claims of his most vociferous critics notwithstanding, he’s neither two-faced nor an apologist for extremism. (Ian Buruma’s New York Times Magazine profile explores Ramadan’s reputation as slippery; Laura Secor in suscriber-only The Boston Globe archive chronicles Ramadan delivering the same message to Muslim and non-Muslim audiences.) However, as an articulate thinker who has assumed the burden of convincing Western Muslims that there is no conflict between their religious identity and their role as citizens of secular Western democracies – and as an interpreter between Islamism and the secular West – he is in a unique role to confront this quandary. He wants to be a bridge, and he seems to have the temperament and intellect to tackle that role.

Many Western critics, however, still aren’t interrogating Islamic thinkers and leaders with any granularity or nuance, talking as if all religious Muslims thought part and parcel with fundamentalist Wahabbis. A tract distributed at the event by one Lorna Salzman entitled “The Muslim Suppression of Free Speech: An Abridged History” comes from that blinkered tradition. Ramadan himself is a victim of “Muslim suppression of free speech,” if properly understood; in addition to being banned from the United States for so many years, he is still prohibited from speaking in six majority-Muslim countries. Their authoritarian rulers clearly consider the Oxford professor a greater threat than the West does. For his part, Ramadan should take head on this well of doubt about the Islamic world’s contemporary history and problem with violent extremists, and craft an unapologetic response that doesn’t fear apologizing when appropriate. Dialogue and a more nuanced view of Islam by the skeptical quarters of the West won’t begin until both parties have taken a step closer to the riverbanks from which they contemplate one another.

Hamas U.

GAZA – Behind the arabesque arches of the five-story university library here, students occupy every available seat, cramming for finals in their humanities classes. Outside, a lucky few nap beneath palm and ficus trees on the cramped urban campus. At lunch, engineering students balance their books upright in the cafeteria and absent-mindedly munch subsidized falafel. This is exam period at the Islamic University of Gaza, charged with the bustle and anxiety of college life.

The first sign that this is a different place from the Western universities it resembles comes when a bell rings in the library. Quickly the students on odd-numbered floors – all men – gather their books and file into the stairwells. Women file in to take their turn. In keeping with a puritanical interpretation of Islamic law, men and women aren’t allowed to study together, so they switch floors every two hours. They lounge in separate student unions and eat in separate cafeterias. At intervals during the day, the call to prayer sounds from the minarets of the campus mosque, and classes come to a halt.

Their strict observance might sound extreme, but the Islamic University is no fringe institution: It’s the top university in Gaza. The majority of students here study secular topics; not all of them are even religious. If you want to get a degree in Gaza, a territory that is home to more than a million people, it’s simply the best place to go.

At the same time, the university is something else again: the brain trust and engine room of Hamas, the Islamist movement that governs Gaza and has been a standard-bearer in the renaissance of radical Islamist militant politics across the Middle East. Thinkers here generate the big ideas that have driven Hamas to power; they have written treatises on Islamic governance, warfare, and justice that serve as the blueprints for the movement’s political and militant platforms. And the university’s goal is even more radical and ambitious than that of Hamas itself, an organization devoted primarily to war against Israel and the pursuit of political power. Its mission is to Islamicize society at every level, with a focus on Gaza but aspirations to influence the entire Islamic world.

In recent decades, as Islamism has grown from a set of isolated radical movements to a fully realized political philosophy, its powerful fusion of intellect, pragmatism, and fundamentalist faith has refashioned societies from the Gulf to Turkey, Egypt to Pakistan. For outsiders who want to understand its power and appeal, the Islamic University of Gaza is probably the best place to begin.

When the Islamic University was founded in 1978, there wasn’t a single institution of higher education in the Gaza Strip. Its founders were members of the militant Muslim Brotherhood, believers that society should be organized according to Koranic principles, and they conceived the university as a sort of greenhouse for their brand of pure, uncompromising Islamism. At the time, Gaza was a freewheeling resort city, its seaside restaurants full of visiting Israelis and Egyptians attracted by Gaza’s famous grilled fish. Secular Palestinians dominated society and the power structure in the 1970s, and scoffed at the prospect of Islamists making inroads. Read the rest of the story in The Boston Globe’s Sunday Ideas section…

Engaging With Terrorists?

My students at Columbia are investigating American policy toward terrorist-designated non-state actors. They’re talking to American policy-makers, analysts and diplomats about Washington’s approach to intelligence-gathering and deal-making. They’re also looking at the experiences of other governments: Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, members of the European Union. By the time they finish their project in May, they should have some concrete ideas about what works, what doesn’t, and ways that the Uunited States might more effectively promote its national interests.