What will give Egypt’s leader ‘legitimacy’?

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

CAIRO — The troop of bearded Islamists carried wooden clubs and wore motorcycle helmets. They marched in time beneath a sweltering noonday sun, rehearsing for the clashes they expected any minute with the Egyptian army. A military ultimatum was set to expire that evening, and the president was about to be deposed.

When they finished their drill, however, they didn’t want to talk about street fighting. Instead, they started a heated debate over a point of political theory—specifically, whether it is acceptable to question the legitimacy of a popularly elected leader.

“If they threaten President Morsi’s legitimacy, everyone will pay for it. There will be an Islamic revolution,” said a 49-year-old construction worker named Taha Sayed Ali, a lifelong member of Gamaa Islamiya, the group that waged an armed insurgency in Egypt in the 1990s.

What grants legitimacy to a leader? The question usually arises in the abstract realm of political theory, but in today’s Egypt, it has become one of visceral, daily importance. How big does a crowd of protesters have to be to indicate an elected leader is no longer the voice of his people? When do self-interested or authoritarian policy decisions go so far as to invalidate the mandate of an elected government? On the streets of Cairo, these questions have come to occupy the center of a serious, messy conversation about how to build a healthy and accountable new state.

Many supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohammed Morsi, who was ousted just after the demonstration, argue that an election confers a legitimacy that only another fair election can take away. They are challenged by a coalition of secular liberals and nationalists, who suggest that even a fairly elected ruler can lose his legitimacy if he fails to deliver on his responsibilities to his citizens. The result, in Egypt, has been a popularly elected leader ousted by what many are calling a “legitimate coup”—an idea that would be almost unimaginable in the longstanding democracies of the West.

“People must believe that we are legitimate, that we represent the majority, or else there is no hope,” said Basem Kamel, a liberal politician who supported the unseating of Morsi and who is determined that the military’s intervention not be seen as a coup. “The only guarantee is the people.”

The Egyptian people are aware that if they’re going to establish a government they all can believe in, they’ll need to settle on a shared understanding of what gives a leader authority and how to determine when a government has lost it. They aren’t there yet. In his final speech before being deposed, ex-president Morsi used the Arabic word for legitimacy—shar’iya —56 times, as though it might serve as a protective cloak against mounting public unrest. With Morsi out and the clashes that followed injuring hundreds and killing dozens, it’s clear that his mere insistence was not enough.

As the debate over legitimacy plays out in Morsi’s wake, the questions at stake resonate far beyond Egypt. The same issues apply in other Arab states in transition, as well as in other countries that have some trappings of democratic rule but are plagued by weak checks and balances and corrupt, authoritarian rulers. As Egypt sorts it out, the country is blazing a path forward that Egyptians, political theorists, and others in the Arab world are watching anxiously.

***

FOR MUCH OF world history, “legitimacy” wasn’t a question at all—kings ruled by force and claimed legitimacy from a divine order. The modern belief that “legitimacy” can be defined by the people themselves—even that it derives from their consent—dates back at least to the influential writings of John Locke in the 17th century. Political philosophers have debated how legitimacy is created ever since, but a common idea runs through all the different views: To establish its legitimacy, a government must fulfill its core obligations to protect its people and help them thrive.

Today the broad consensus in the West is that legitimacy arises from the voting booth. Citizens should be able to have profound, even violent, disagreements about the direction of their nation without questioning the basic legitimacy of the government; if they want to depose the party in power, they can do so in the next election.

The revolutionary forces that overthrew Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak in 2011 tried to establish a new system that might enjoy this kind of popular legitimacy. There would be elections and a process to write a constitution. The president, duly elected, was the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohammed Morsi. Voters also chose an overwhelming Islamist majority for Parliament.

In the presidential runoff, Morsi explicitly appealed to voters who hadn’t chosen an Islamist in the first round but were convinced by his promise that he would govern with everyone’s interests in mind. At the time, even critics of the Brotherhood and the revolution conceded that the ballot was fair and the new president legitimate.

That, however, is where agreement ended. The president proceeded to push through laws—and, ultimately, a new national constitution—without buy-in or input from the opposition. Morsi ditched all his non-Islamist allies. The ruling Muslim Brotherhood and its even more conservative Salafi allies believed they had public support to enact their platform, which among other things called for a doctrinaire application of Islam to the law. In effect, they claimed both God and the electorate on their side. At one point, after the Parliament had already been disbanded, Morsi tried to put himself above judicial review, which would have left his authority with no check at all.

To the politically broad spectrum of Egyptians who had helped overthrow the previous absolute leader, the president had overstepped. On the one-year anniversary of Morsi’s inauguration, at the behest of the Tamarod, or Rebel, campaign, millions took to the streets. In advance, the Tamarod organizers claimed to have gathered 22 million signatures of citizens demanding Morsi’s ouster—significantly more than the 13.2 million who voted for him. By failing to rule either effectively or inclusively, the organizers of the Tamarod petition said, Morsi had lost “ethical, legal, and popular legitimacy.” Their petition cited his administration’s practical failures and the fact that it had rammed through a new constitution with no regard for the objections of sizable chunks of his own citizenry, including secularists, Christians, and women. They even coined a new term to describe the authoritarianism of a fairly elected leader: “ballotocracy.”

By this definition of legitimacy, the ballot box isn’t the last word. In essence, the Egyptian protesters were turning to a tradition that sees the roots of legitimacy in justice and in tangible results. The American Civil Rights movement made similar arguments: It didn’t matter if Jim Crow followed the letter of the law in Mississippi, or had the support of a majority; in failing so many of its citizens, it forfeited legitimacy. This broader notion of legitimacy underlay the original rebellion against Hosni Mubarak’s dictatorship, and prompted the June 30 uprising and the coup that followed. By this way of thinking, how a leader rules may matter more than how that leader came to power.

***

IT MIGHT SEEM strange to have to choose between majority rule or inclusive governance as sources for legitimacy; one tends to think legitimacy requires both. But in the kind of government Egypt is trying to establish, which will have to satisfy a significant Islamist constituency, that balance is not so easy. A state can’t be driven purely by majority interest and also protect the rights of its minority groups. It cannot be both Islamic and secular. And, yet somehow, the various factions must agree to respect the governance of whoever ends up in power, or the messy business of writing laws and addressing the nation’s ills will never get underway.

Esam Haddad, one of Morsi’s closest advisers, wrote in a posting on his Facebook page that the coup interrupted a legitimate political process. “In a democracy, there are simple consequences for the situation we see in Egypt: the President loses the next election or his party gets penalized in the upcoming parliamentary elections,” Haddad said. “Anything else is mob rule.”

Others think that in Egypt right now, proper electoral process isn’t enough. Critics of Brotherhood rule, like Brookings Institution fellow H.A. Hellyer (who coined the term “popularly legitimate coup”), argue that any ruler of Egypt today needs to at least address, if not solve, the country’s vast economic crisis while also appearing sensitive to popular opinion. Morsi, Hellyer says, had legal legitimacy but lost all popular legitimacy. “With theoretical legal legitimacy alone, no executive can function,” Hellyer said. Now, the transitional president appointed by the military faces the same challenge.

With enough will to cooperate, some of the problems of the Egyptian state may be reconciled. The experience of the West suggests that, given enough checks and balances, majority rule through popular elections is compatible with minority rights. Other directions for the state may be mutually exclusive, like theocratic concepts of justice and secular law.

How Egypt attempts to resolve these tensions could prove pathbreaking. In modern times, there have been cases like Iran, where an Islamist majority simply overwhelmed the country’s secular faction; or like India and Indonesia, where pluralism and minority rights were instituted initially by fiat, and haven’t always survived intact when put to electoral test.

In the coming months, whether Egypt manages to confer a lasting legitimacy on any particular governmental arrangement will go a long way to foretelling where the country is headed. Arguments over legitimacy quickly veer into dangerous territory; once the discussion is about who is morally right, rather than a simple power struggle or policy disagreement, it becomes hard to give the other side any credit whatsoever. Ultimately Egypt will settle on some governmental solution and see its constitution harden into established practice. But so long as the sole arbiter is not law but legitimacy, the people will remain on high alert, ready to spill back out into the street.

The government installed by the coup doesn’t include any Islamist members, repeating the exclusionary practice of the Muslim Brothers it replaced—a move that is sure to leave all this government’s decisions subject to a legitimacy challenge by Islamists. This toxic cycle will continue until legitimacy becomes not a rhetorical feint but a reality. It’s the first and most vital step toward a viable rule of law.

Egypt’s Free-Speech Backlash

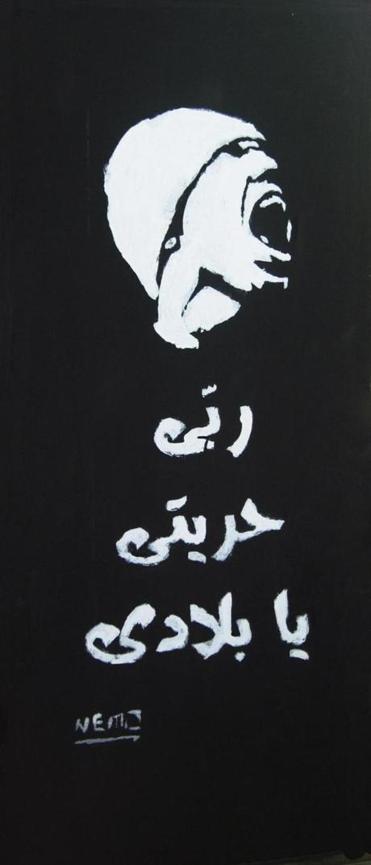

A street poster from Cairo that reads, “My God, my freedom, O my country.” Photo: NEMO.

[The Internationalist column in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

CAIRO — Every night, Egypt’s current comedic sensation, a doctor hailed as his country’s Jon Stewart, lambastes the nation’s president on TV, mocking his authoritarian dictates and airing montages that reveal apparent lies. On talk shows, opposition politicians hold forth for hours, excoriating government policy and new Islamist president Mohammed Morsi. Protesters use the earthiest of language to compare their political leaders to donkeys, clowns, and worse. Meanwhile, the president’s supporters in the Muslim Brotherhood respond in kind on their new satellite television station and in mass counter-rallies.

Before Egypt’s uprising two years ago, this kind of open debate about the president would have been unthinkable. For nearly three decades, former president Hosni Mubarak exerted near total control over the public sphere. In the twilight of his term, he imprisoned a famous newspaper editor who dared to publish speculation about the ailing president’s declining health. No one else touched the story again.

To Western observers, the freewheeling back-and-forth in Egypt right now might sound like the flowering of a young open society, one of the revolution’s few unalloyed triumphs. But amid the explosion of debate, something less wholesome has begun to arise as well. Though speech is far more open, it now carries a new and different kind of risk, one more unpredictable and sudden. Islamist officials and citizens have begun going after individuals for crimes such as blasphemy and insulting the president, and vaguer charges like sedition and serving foreign interests. The elected Islamist ruling party, the Muslim Brotherhood, pushed a new constitution through Egypt’s constituent assembly in December that expanded the number of possible free speech offenses—including insults to “all prophets.”

Worryingly, a recent report showed that President Morsi—a Brotherhood member, and Egypt’s first-ever genuinely elected, civilian leader—has invoked the law against insulting the presidency far more frequently than any of the dictators who preceded him, and has even directed a full-time prosecutor to summon journalists and others suspected of that crime.

The Muslim Brotherhood, as it rises to power, is playing host to conflicting ideas. It wants the United States to view it as a tolerant modern movement that doesn’t arbitrarily silence critics, but at the same time it needs to show its political base of socially conservative constituents in rural Egypt that it won’t tolerate irreligious speech at home. And it wants to argue that despite its religious pedigree, it is behaving within the constraints of the law.

For the time being, Egypt’s proliferating free expression still outstrips government efforts to shut it down. But as the new open society engenders pushback, what’s happening here is in many ways a test case for Islamist rule over a secular state. What’s at stake is whether Islamists—who are vying for elected power in countries around the Muslim world—really only respect the rules until they have enough clout to ignore them.

***

The text on this Cairo street poster reads, “As they breathe, they lie.” Photo: NEMO

EGYPTIANS ARE RENOWNED throughout the Arab world for jokes and wordplay, as likely to fall from the mouth of a sweet potato peddler as a society journalist. Much of daily life takes place in the crowded public social spaces where people shop, drink hand-pressed sugarcane juice, loiter with friends, or picnic with their families. But under the stifling police state built by Mubarak, that vitality was undercut by fear of the undercover police and informants who lurked everywhere, declaring themselves at sheesha joints or cafes when the conversation veered toward politics.

As a result, a prudent self-censorship ruled the day. State security officials had desks at all the major newspapers, but top editors usually saved them the trouble, restraining their own reporters in advance. In 2005, when one publisher took the bold step of publishing a judge’s letter critical of the regime, he confiscated the cellphones of all his editors and sequestered them in a conference room so they couldn’t tip off authorities before the paper reached the streets.

It wasn’t technically illegal to be a dissident in Egypt; that the paper could be published at all was testament to the fact that some tolerance existed. Egypt’s system was less draconian and violent than the police states in Syria and Iraq, where dissidents were routinely assassinated and tortured. But the limits of public speech were well understood, and Egyptians who cared to criticize the state carefully stayed on the accepted side of the line. Activists would speak out about electoral fraud by the ministry of the interior or against corruption by businesspeople, for example, but would carefully refrain from criticizing the military or Mubarak’s family. Political life as we understand it barely existed.

Egypt’s uprising marked an abrupt break in this long cultural balancing act. For the first time, millions of Egyptians expressed themselves freely and in public, openly defying the intelligence minions and the guns of the police. It was shocking when people in the streets called directly for the fall of the regime. Within weeks, previously unimaginable acts had become commonplace. Mubarak’s effigy hung in Tahrir Square. Military generals were mocked as corrupt, sadistic toadies in cartoons and banners. Establishment figures called for trials of former officials and limits on renegade security officials.

In the two years since, free speech has spread with dizzying speed—on buses, during marches, around grocery stalls, everywhere that people congregate. Today there are fewer sacred cows, although even at the peak of revolutionary fervor few Egyptians were willing to risk publicly impugning the military, which was imprisoning thousands without any due process. (An elected member of parliament faced charges when he compared the interim military dictator to a donkey.)

Mohammed Morsi was inaugurated in June, after a tight election that pitted him against a former Mubarak crony. Morsi campaigned on a promise to excise the old regime’s ways from the state, and on a grandiose Islamist platform called “The Renaissance.” His regime has fared poorly in its efforts to take control of the police and judiciary. Nor has it made much progress on its sweeping but impractical proposals to end poverty and save the Egyptian economy. It has proven easier to talk about Islamic social issues: allegations of blasphemy by Christians and atheist bloggers; alcohol consumption and the sexual norms of secular Egyptians; and the idea, widely held among Brotherhood supporters, that a godless cabal of old-regime supporters is secretly plotting to seize power.

Before it won the presidency, the Muslim Brotherhood emphasized it had been fairly elected; the party was Islamist, it said, but from the pragmatic, democratic end of the spectrum. But in recent months, there’s been more than a whiff of Big Brother about the Brotherhood. Supposed volunteers attacked demonstrators outside Morsi’s presidential palace—and then were videotaped turning over their victims to Brotherhood operatives. Allegations of torture, illegal detention, and murder by state agents pile up uninvestigated.

As revolutionaries and other critical Egyptians have turned their ire from the old regime to the new, the Brotherhood also has begun targeting political speech. The new constitution, authored by the Brotherhood and forced through Egypt’s constituent assembly in an overnight session over the objections of the secular opposition and even some mainstream religious clerics, criminalized blasphemy and expanded older statutes against insults to leaders, state institutions like the courts, and religious figures. Popular journalists have been threatened with arrest, while less famous individuals, including children improbably accused of desecrating a Koran, have been thrown into detention. Morsi’s presidential advisers regularly contact human rights activists and journalists to challenge their reports, a level of attention and pressure previously unknown here.

In addition to the old legal tools to limit free expression, which are now more heavily used by the Islamists than they were by Mubarak, the new constitution has added criminal penalties for insulting all religions and empowers courts to shut down media outlets that don’t “respect the sanctity of the private lives of citizens and the requirements of national security.”

The Egyptian government began an investigation of TV comedian Baseem Yousef but dropped its charges after a public outcry.

Egyptian human rights monitors have tracked dozens of such cases, including three that were filed by the president’s own legal team. Gamal Eid at the Arab Network for Human Rights Information charted 40 cases that prosecuted political critics for what amounted to dissenting speech in the first 200 days of Morsi’s regime. That’s more, he claims, than during Mubarak’s entire reign, and more charges of insulting the president than were filed since 1909, when the law was first written.

***

IT’S A WELL-KNOWN PRECEPT in politics that times of transition are the most unstable, and that the fight to establish civil liberties carries risks. The current speech crackdown may just be an expected symptom of the shift from an effective authoritarian state to competitive politics. Mubarak, of course, had less need to prosecute a population that mostly kept quiet.

It could also be a sign of desperation on the part of the Brotherhood, as it struggles to rule without buy-in from the police and state bureaucracy. Or it could, more alarmingly, mark a transition to a genuine new era of censorship in the most populous Arab country, this time driven as much by the Islamist cultural agenda as by the quest to keep a grip on power.

It is that last prospect that makes the path Egypt takes so important. By dint of its size and cultural heft, the country remains a major influence across the Arab world, and both in Egypt and elsewhere, the Muslim Brotherhood is at the front lines of political Islam—trying to balance the cultural conservatism of its rank-and-file supporters with the openness the world expects from democratic society.

There are signs that the Brotherhood wants to at least make gestures toward Western norms, though it remains hard to gauge exactly how open an Egypt its members would like to see. At one point the government began an investigation of Baseem Yousef, the Jon Stewart-like TV comedian, but abruptly dropped its charges in January after a public outcry.

During the wave of bad publicity around the investigation, one of President Morsi’s advisers issued a statement claiming that the state would never interfere in free speech—so long as citizens and the press worked to raise their “level of credibility.”

“Human dignity has been a core demand of the revolution and should not be undermined under the guise of ‘free speech,’” presidential adviser Esam El-Haddad said in a statement that placed ominous boundaries on the very idea of free speech that it purported to advance. “Rather, with freedom of speech comes responsibility to fellow citizens.”

What scares many people, is how they define “responsibility.” A widely watched video clip portrays a Salafi cleric lecturing his followers about how Egypt’s new constitution will allow pious Muslims to limit Christian freedoms and silence secular critics (the cleric, Sheikh Yasser Borhami, is from a more fundamentalist current, separate from but allied with the Brotherhood). When critics look at the Brotherhood’s current spate of investigations and threatened prosecutions, they see the political manifestation of the same exclusionary impulse: the polarizing notion that the Islamists’ actions are blessed by God and, by implication, that to criticize them is sacrilege.

Modern Islamism hasn’t reckoned with this implicit conflict yet, even internally. Officially, one current of the Brotherhood’s ideology prioritizes social activism over politics, and eschews coercion in religious matters. But another, perhaps more popular strain in Brotherhood thinking agitates for a religious revolution in people’s daily lives, and that strain appears to be driving the behavior of the Brothers suddenly in charge of the nation. Their fervor is colliding squarely with the secular responsibility of running a state like Egypt, which for all its shortcomings has real institutions, laws, and a civil society that expects modern freedoms and protections. The first stage of Egypt’s transition from military dictatorship has ended, but the great clash between religious and secular politics is just beginning to unfold.

Is Anyone Ready to Actually Lead Egypt?

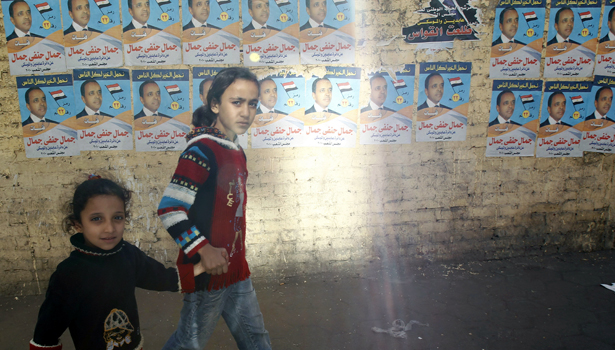

Girls walk past Muslim Brotherhood campaign posters in Cairo. (Reuters)

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

The Muslim Brotherhood is inflexible and exclusive, the military power-hungry and self-interested, liberals are in disarray, and a country that badly needs cooperation is once again plagued by division.

CAIRO, Egypt — The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi appears to have won Egypt’s first contested presidential election in history, a mind-boggling reversal for the underground Islamist organization whose leaders are more familiar with the inside of prisons than parliament. Whether or not Morsi is certified as the winner on Thursday — and there is every possibility that loose-cannon judges will award the race to Mubarak’s man, retired General Ahmed Shafiq — the struggle has clearly moved into a new phase that pits political forces against a military determined to remain above the government.

The ultimate battle, between revolution and revanchism, will remain the same whether Morsi or Shafiq is the next president. It’s going to be a mismatched struggle, one that will require unity of purpose, organization, and the sort of political muscle-flexing that has escaped civilian politicians for the entire 18-month transition process. If they can’t marshal a strong front on behalf of a unified agenda, they are likely to fail to wrestle the most important powers out of the military’s stranglehold.

After a year and a half in direct control, Egypt’s ruling council of generals (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF) appears to have grown fond of its power. As the presidential vote was being counted, SCAF issued a new temporary constitution that gives it almost unlimited powers, far greater than those of the president. It can effectively veto the process of drafting the new permanent constitution, and it retains the power to declare war.

“We want a little more trust in us,” a SCAF general said in a surreal press conference on Monday. “Stop all the criticisms that we are a state within a state. Please. Stop.”

In fact, all the military’s moves, right up to the last-minute dissolution of parliament and the 11th-hour publication of its extended, near-supreme powers, give Egyptians every reason to distrust it. Sadly, the alternatives are not much more reassuring.

Shafiq, the old regime’s choice, mobilized the former ruling party with an unapologetic, fear-driven campaign, drumming up terror of an Islamic reign while promising a full restoration to Mubarak’s machine. If he ends up in the presidential palace, he could place the secular revolutionaries and the Muslim Brotherhood in harmony for the first time since the early days of Tahrir Square.

Morsi, meanwhile, is known as an organization enforcer, not as a gifted politician or negotiator — which are the skills most in need as Egypt embarks on its high-risk struggle to push aside a military dictatorship determined to remain the power behind the throne.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate has few assets in his corner. He represents the single best-organized opposition group but doesn’t control it. Revolutionary and liberal forces are in disarray. Mistrust, even hatred, of the Muslim Brotherhood has flared among groups that should be the Brotherhood’s natural allies against the SCAF. And the Brotherhood itself has wavered between cutting deals with the military and confronting it when the military changes the terms. Many secular liberals say they relish the idea of the dictatorial military and the authoritarian Islamists fighting each other to exhaustion.

All this division promises a chaotic and difficult transition for Egypt after 18 months of direct military rule. If officials honor the apparent results (an open question, since the elections authority is run by SCAF cronies), Morsi will head an emasculated, civilian power center in the government that will have little more than moral suasion and the bully pulpit with which to face down the SCAF.

While the military’s legal coup overshadows the election results, it doesn’t render them meaningless. The presidency carries enormous authority; managed successfully, it’s the one institution that could begin to counter and undo the military’s evisceration of law and political life.

The example of parliament is instructive. Some observers said from the beginning that a parliament under SCAF would have no real power. But that didn’t turn out to be the problem with the Islamist-controlled parliament. It had symbolic power, and it could pass laws even if the SCAF then vetoed them. What made the parliament a failure was its actual record. It didn’t pass any inspiring or imaginative laws, it repeatedly squashed pluralism within its ranks, and it regularly did SCAF’s bidding. That’s what discredited the Brotherhood and its Salafi allies and led to their dramatic, nearly 20 percent drop in popularity between the parliamentary elections and the first round of presidential balloting five months later.

It would be greatly satisfying if the corrupt, arrogant, and authoritarian machine of the old ruling party were turned back, despite what appears to have been hints of an old-fashioned vote-buying campaign and a slick fear-mongering media push, backed by state newspapers and television. On election day, landowners in Sharqiya province told me the Shafiq campaign was offering 50 Egyptian pounds, or about $8.60, per vote.

But it would be greatly unsatisfying for that victory to come in the form of a stiff and reactionary Muslim Brotherhood leader who appears constitutionally averse to coalition-building and whose political instincts seem narrowly partisan, at a time when Egypt’s political class is locked in death-match with the nation’s military dictators.

Egypt’s second transition could last, based on the current political calendar, anywhere from six months to four years. A new constitution will have to be written and approved, likely with heavy meddling from the military and with profound differences of philosophy separating the Islamist and secular political forces charged with drafting it. A new parliament will have to be elected. And then, possibly, the military (or secular liberals) could force another presidential election to give the transitional government a more permanent footing.

Meanwhile, during this turbulent period, Egypt will have to contend with the forces unleashed during the recent, bruising electoral fights.

Shafiq’s campaign brought into the open the sizable constituency of old regime supporters (maybe a fifth of the electorate, based on how they did in recent votes) and Christians terrified that their second-class status will be grossly eroded under Islamist rule.

Liberals will have to explain and atone for their stands on the election. Many of them said they would prefer the “clarity” of a Shafiq victory to a triumphalist Islamic regime under Morsi, and cheered when parliament was dissolved — appearing hypocritical, expedient, and excessively tolerant of military caprice.

The Brotherhood still hasn’t made a genuine-seeming effort to placate and include other revolutionaries, spurning entreaties to form a more inclusive coalition. It attempted, twice, to force through a constitution-writing assembly under its absolute control. Yet, once more, the Brotherhood has a chance to save itself. So far, at each such juncture it has chosen to pursue narrow organizational goals rather than a national agenda. It would be great for Egypt if the Brotherhood now learned from its mistakes, but precedent doesn’t suggest optimism.

Partisans of both presidential candidates told me they expected a big pay-off when their man won: cheaper fertilizer, free seeds, a flood of affordable housing, jobs for all their kids, better schools. None of these things is to be expected in the near future under any regime in Egypt. Disappointment is sure to proliferate as everyone realizes how difficult Egypt’s long slog will be.

There’s much hand wringing among Egyptians about the last-minute power grab by the military through the sweeping constitutional declaration it published on Sunday. In a land of made-up law and real power, why the obsession with power-mad generals, co-opted judges, and the arbitrary declarations they publish? SCAF’s decisions only matter because of its raw power, tied to the gunmen it has deployed on the streets and its willingness to use them against unarmed civilians. This inequity will only change with a shift in actual power, not because of a clever and just redrafting of laws. An elected president, or a defenestrated parliament for that matter, could issue its own, better constitution and declare it the law of the land, and enter a starting contest with SCAF. Authority belongs to whomever claims it and can make it stick.

Inside the Three-Way Race for Egypt’s Presidency

Leading Egyptian presidential candidates Amr Moussa, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, and Mohamed Morsi. / Reuters, AP

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

CAIRO — Egypt’s first real presidential contest ever, for which the candidates met last night for the Arab world’s first-ever real presidential debate, has all the makings of a genuinely interesting fight. The front-runners nicely capture a wide stretch of the spectrum, while leaving out the extremes. Voter interest appears high, and the military rulers seem unlikely to allow major fraud based on their record with parliamentary elections.

But enthusiasm about the debate should not obscure the unsatisfying circumstances of the presidential election, which itself does not guarantee a full transition to civilian rule or democracy.

The president’s powers still have not been delineated, and the significance of the race and its victor could be heavily tarnished by future decisions about the assembly that will write the next constitution, among other unresolved questions about whether Egypt will have a presidential, parliamentary, or hybrid system.

Islamists have proven themselves to be the dominant political bloc, garnering more than two-thirds of the vote in parliamentary elections earlier this year. The winner of the presidential race, even if he is secular, will owe his victory to Islamist voters, and will have to govern in tandem with a parliament that has a veto-proof Islamist majority. Islamist politics are malleable and by no means monolithic, but they will drive the political agenda after decades of total exclusion.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF, has heavily manipulated the process, deepening its unaccountable and authoritarian mechanisms of control. Crony-packed courts and the presidential election commission have made a series of arbitrary decisions. Egypt’s next government will have to negotiate artfully to wrest the most important powers out of the hands of generals.

The campaign has galvanized Egyptians. This week, the candidates crisscrossed the countryside in bus caravans, and thousands turned out in even the minutest villages.

“He has a special charisma,” gushed an English teacher named Ahmed Abdel Lahib, during a pit stop by the Amr Moussa campaign in a Nile Delta hamlet called Mit Fares. “Egypt needs a man like him,” he said of the former Arab League secretary-general.

Hundreds of men thronged the candidate, shouting, “Purify the country!” and “We want to kiss you!” In his tailored suit, and carrying the patrician demeanor he honed over decades as Egypt’s foreign minister and then Arab League chief, Musa clambered onto a makeshift stage for his short stump speech (fix agriculture, the economy, and health care, long live Egypt!). Men pushed over chairs and slammed one another into the walls of the narrow alley to get closer to Moussa and touch his sleeve.

The oaths of loyalty felt a tad staged and excessive, but similar displays characterized all the major candidate rallies, and could reflect the old authoritarian rallies, or a desire for a galvanizing leader like Gamal Abdel Nasser, the nationalist colonel who took power in a 1952 coup, or simply the enthusiasm of voters who for the first time in their lives will likely get to choose their president.

Moussa has presented himself as a secular elder statesman who can stand against what he portrays as a power-hungry Islamist tide, personified by the other two front-runners: the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi and the ex-Muslim Brother Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. It is Aboul Fotouh who most worries Moussa’s strategists: he is giving the former minister a run for first place, marketing himself as potential bridge candidate, a “liberal Islamist” who can appeal to Islamists as well as the secular nationalists and revolutionaries who are wary of Moussa’s connections to the old regime.

Thousands of fans in the market town of Senbelawain waited hours on a recent night for Aboul Fotouh, who seems perpetually delayed by traffic (he was late for the historic presidential debate for the same reason). When he arrived, the retired doctor was greeted like a rock star with swoons and chants. Bearded Salafis and women in full-face-covering niqabs jostled with clean-shaven students.

Aboul Fotouh is a more gripping orator than Moussa, with a gruff, gravelly voice that he controls well, shifting cadence to maintain his audience’s attention. “If this country succeeds, the whole Islamic world succeeds,” Aboul Fotouh shouted, provoking cries of exultation. He talked extensively about sharia, in a way apparently calculated to burnish his Islamist credentials while reassuring his left flank that he opposes such literal interpretations as severing the hands of thieves. Aboul Fotouh’s stump speech played to his Islamist base rather than to his revolutionary and secular sympathizers.

A Muslim Brotherhood member in the audience named Yousef Eid Hamid, 38, said he was campaigning for Aboul Fotouh in defiance of his organization’s strict orders to vote for Morsi. “We are not machines,” he said. “You cannot love a candidate, and then just change.”

Backroom deals with the military will likely be decisive in determining how the winner can govern, but retail politics seem to be taking root for now. During Thursday night’s debate, the two front-runners, Moussa and Aboul Fotouh, dug at each other’s records. Aboul Fotouh portrayed Moussa as a corrupt, weak stooge for Mubarak who will continue the old regime’s authoritarian ways. Moussa attacked Aboul Fotouh as a fire-and-brimstone Islamist who founded a radical group in the 1970s and now disingenuously presents himself as a moderate.

Egyptians crammed cafes to watch. During a half-time walkthrough (the debate lasted more than four hours, from 9:30 p.m. to 2 a.m.) at the Boursa pedestrian arcade behind the Cairo stock exchange, I met several people who had voted for the Muslim Brotherhood for parliament but were leaning toward the anti-Islamist Moussa for president.

“I will give the Muslim Brotherhood domestic policy, but I want to keep them far away from security and foreign policy,” said Abdelrahim Abdullah Abdelrahim, 44, an import-export businessman built like a bouncer. “These Islamists want to march on Al Quds” — Jerusalem — “and wage war. It’s not the time for this.”

He went on to mock the Salafi legislator who tried to sound the call to prayer in parliament, and his Noor Party colleague who tried to claim his nose job bandage was really the scar from a politically motivated assault. “People are more tired than before,” Abdelrahim said as he lost another round of dominoes to a friend.

At the presidential rallies in the Delta, I met numerous voters who were shopping or just checking out the opposition. Leftist revolutionaries, committed to minor candidates guaranteed not to reach the second round, listened to stump speeches to consider whom they’d be willing to hold their noses and vote for in a runoff. Confirmed skeptics came, in case they might change their minds.

Arguments broke out. At the end of one Moussa pit stop in Dikirnis, an older man dismissed the candidate as a “felool,” or remnant of the old regime. Another man pushed him hard in the abdomen: “He is not a felool! Amr Moussa is a great man!” The critic scuttled off to his nephew’s pastry shop, where he continued his invective against Moussa. The nephew, 37-year-old Ahmed Burma, smiled benevolently. “My uncle jumped on the revolutionary bandwagon,” he said. “But I’m supporting Amr Moussa. I run a business with 90 employees. Let’s give this guy a chance to work.”

Still, the polls and predictions are little more than guesswork. Most of the voters live without internet or phones and are beyond the reach of the campaigns’ opinion researchers. Egypt has had only one real election in its modern history: the parliamentary ballot that concluded this January. Twenty-seven million people voted, more than two-thirds of them for Islamist parties.

Even with the Islamist vote split between Aboul Fotouh and the Brotherhood’s Morsi, it’s all but assured that one of them will face Moussa in the runoff June 16 and 17. Morsi might fare better than many analysts seem to think, as the Brotherhood deploys its formidable get-out-the-vote operation, which no other campaign can currently match.

The Islamists in parliament haven’t acquitted themselves well, wasting time on fringe religious debates while the economy sinks, deferring to the army on crucial issues such as military trials for civilians, and alienating almost every major constituency in the country other than their own by trying to impose a constitutional convention packed with Salafist and Brotherhood members.

If turnout is as high as it was for parliament (and it might be higher, since the president has always been the commanding figure in Egypt’s modern political system), Moussa would need to convince more than 6 million people, a full third of those who voted Islamist for parliament, to switch allegiance and vote for him. His advisers believe that’s possible.

They also seem to think that Moussa’s year-long bus tour of rural areas will pay dividends, and that their basic selling point resonates with common voters: a pair of safe, experienced hands for a transition.

Nonetheless, Moussa’s strategy smacks of secular liberal wishful thinking, a common affliction among Egypt’s veteran political class in a year and a half of dynamic change. It might just work out for him, but an equally likely scenario would have the voters that propelled Islamists to parliament eager to give someone with their values more of a chance for success than has been allowed by three months of parliamentary machinations under the shadow of the military.

Judging by the size of the crowd…

… Egypt’s secular liberals are in trouble. I have a lot of reporting on the subject to sift through, but a few weeks of immersion in the burgeoning political party scene here suggest that the new liberal parties have a lot of catching up to do. Perhaps a prohibitive amount.

Above is the crowd at the founding meeting of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party in Kafr El Sheikh, a provincial city in the Nile Delta, earlier this month. It numbered fewer than 200, probably closer to 100 by the end.

Below is a rally last night organized in another Delta city, Shibin El Kom, by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party. The crowd numbered about 2,000, all of whom listened rapt until the end of the three-hour event, replete with detailed policy plans and instructions for cadres. If these number are any indication (and some smart people say they’re not), the Brotherhood is running far stronger than anyone else.

Muslim Brotherhood goes legal

My latest column in The Atlantic considers the turning point reached this week when the Muslim Brotherhood’s political party gained official recognition.

CAIRO, Egypt — This Tueday, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood became a legal political party for the first time since President Gamal Abdel Nasser banned it more than half-a-century ago. The military officers managing Egypt’s transition out of the Age of Mubarak approved the Brotherhood’s new Freedom and Justice Party, the Islamist organization’s chosen vehicle to political power.

After decades in limbo, the Muslim Brotherhood will now have all the benefits of unambiguous legal status — and face all the scrutiny and questioning to which a political behemoth is subjected. The Brotherhood has built its considerable following, and honed its impressive organizational wherewithal, by striving in the shadows against a police state’s full force.

During their decades under the ban, Brothers spread their religious message and delivered what services they could. Now, however, the challenges are vast and political, and the underground methods of a doctrinaire religious group (whose primary mission, always, was spreading a strict message of faith) won’t play the same way on the political stage.

It’s a confusing transition for the Islamist activists trying to reposition their organization from oppressed social group to political strongman.

The Shiny New Muslim Brotherhood

The Muslim Brothers hosted their grand coming-out party on Saturday night. Officially, the occasion marked the opening of their new headquarters, a seven-story monstrosity that looks like an egg-cream ziggurat on a breezy plateau above Islamic Cairo. Unofficially, the event was a declaration that the Brothers have arrived and will be kingmakers during Egypt’s season of political change.

“We’re not banned anymore,” exulted Mohsen Radi, who served a turn in parliament as a representative of a Delta town called Banha. “By the grace of freedom, by the grace of the revolution, we have regained our place.”

As symbols go, the building and its inaugural could not have been more potent. For decades, the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide operated out of a stuffy, dark, low-ceilinged apartment on the isle of Manial, in Cairo’s center. A team of state security men loitered out front. Entering visitors had to clamber over the pile of shoes in the hallway, between the elevator and the door. Senior officials would conduct interviews in the corner of the same room where the rest of the leadership was deliberating.

It was, to say the least, a no-frills operation, highlighting the Brotherhood’s ambiguous status as a legally prohibited but semi-tolerated organization.

Between 2005 and 2009, when the Brothers held 88 parliamentary seats, the organization opened a slightly more spacious parliamentary office nearby. State security forbade them from organizing any large public events, and even their annual Ramadan iftaar was cancelled. During functions there, the power often mysteriously cut out, with a frequency that the Brotherhood accepted as one of the more petty manifestations of state harassment.

Now, however, the Brotherhood is freely exercising its organizational muscle. Since Mubarak was run out of office, the Muslim Brotherhood has opened offices in every province. It is launching its own satellite television network. It has entered coalition talks with other groups, and has founded its own political party, called Freedom and Justice, which has a Christian vice president. At first, in an effort to comfort worried Christians and secularists, the Brotherhood said it would contest only 30 percent of the seats in parliament, and wouldn’t run a presidential candidate. Last week, it raised the ante, now saying it will compete for half the parliamentary districts.

With the opening of the new official headquarters in Moqattam, the transformation is complete. Bright lights illuminate the party logo in English and Arabic – a pair of green crossed swords.

About a hundred movement activists prayed outside before the official opening on Saturday night (the building’s been in use for weeks already). They chanted the Brotherhood motto in unison:

God is great.

The Prophet is our teacher.

The Koran is our constitution.

Jihad is our way.

Martyrdom is our goal.

Then they stormed into the building and emptied trays of fruit juice.

In a sign of the Brotherhood’s political heft, a parade of notables came to pay respects, including presidential front-runner and former Arab League chief Amr Moussa and a coterie of other secular politicians and judges.

In a rear lot behind the headquarters, more than a thousand supporters assembled in a dirt lot covered with carpets for the occasion. A band sang paeans to freedom, brotherhood, and the Brotherhood.

Khairat Shater, a millionaire and number-two official in the Brotherhood credited with being one of its most powerful fixers, grinned just beside the stage.

“Where do you think state security is now?” I asked. At the last Brotherhood function I attended, an iftaar in the parliamentary offices in August, the number of plainclothes intelligence officers hovering around the event equaled that of the Brotherhood officials inside.

“They haven’t gone home,” he said. “They’re around here somewhere.”

If one were keeping score, however, the Brotherhood would look to be ahead.

Fresh Air

Terry Gross interviewed me on Fresh Air today about the events in Egypt and their potential to create new space in Arab politics. From the Fresh Air website:

All of our assumptions about the Arab world have been turned on their heads in the past month, says veteran Middle East correspondent Thanassis Cambanis.

“Everything that the experts say and everything that the activists and politicians have taken for granted for a generation, at least, is really off the table,” he tells Fresh Air‘s Terry Gross. “What’s been happening, first in Lebanon and then in Tunisia and now in Egypt and who knows further afield, suggests that new forces have been unleashed and we have no idea where they might lead and what new dynamics they might create.”

On Wednesday’s Fresh Air, Cambanis puts what has been going on in Egypt in a historical context — and explains the rising influence of the political party Hezbollah in the region. He says the recent explosion of popular anger and activism in Egypt opens up the possibility for a new political movement — one not endorsed by autocratic regimes or rooted in Hezbollah’s Islamist ideology.

“There are a lot of people, both dispossessed and powerful, who want dignity but they don’t necessarily want endless war — which is what the Hezbollah school of thought advocates,” he says. “I think they would be hungry for, and very receptive to, an Egypt-centered political movement that talks about Arab empowerment but not endless war.”

Things We Don’t Know

The unraveling of Mubarak’s regime has proceeded at a tremendously exciting pace over the weekend, spawning news, uncertainty, as well as a layer of ideologically-motivated posturing in the U.S. that is only confusing our still-murky view of the situation.

The unraveling of Mubarak’s regime has proceeded at a tremendously exciting pace over the weekend, spawning news, uncertainty, as well as a layer of ideologically-motivated posturing in the U.S. that is only confusing our still-murky view of the situation.

We still don’t have a full picture of exactly what’s happening now in Egypt. We don’t know what’s happening inside the military and inside the top levels of the regime. We don’t know exactly what kind of schemes the police have implemented, although there’s evidence of undercover cops looting and trying to provoke chaos. We don’t know how motivated the protesters are to organize for the long term – although we do know their actions until now have defied almost all expert predictions. We don’t know how many people have been killed and arrested. And we hardly know what’s happened beyond Cairo and Alexandria. We don’t know how it will all turn out.

Given that vast uncertainty, it’s all the more important that we don’t let ideologues exaggerate what we do know, or paint false pictures of the players involved. We do know that almost all of the protests have eschewed the language of Islamism, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the weak establishment opposition parties. We do know that most Egyptians don’t consider Mohammed ElBaradei an inspiring or charismatic figure, and that until this weekend most activists (secular as well as Islamists) viewed his year-long debut in Egyptian politics with disappointment or even frustration. We know that the Muslim Brotherhood has been reluctant to challenge Mubarak’s regime – declining to join bolder secular parties in boycotting last fall’s parliamentary elections, and sitting out the first rounds of the “Days of Anger” this January. Finally, we know that Egypt’s suffocated civil society boasts only a few institutions with national organizational reach: the military, the state security organs, the ruling National Democratic Party, the Muslim Brotherhood, and possibly the Coptic church. Even if they play little or no role in the protests, they’ll be positioned to capitalize most quickly on a post-Mubarak order.

When an authoritarian state collapses, it’s wise to watch players with existing capacity. It’s even wiser to recall that all bets are off. Once-omnipotent secret police can vanish in a day (it happened in Iraq in 2003). New populist parties can quickly emerge. Dormant or smothered institutions like labor unions can quickly reemerge with vigor, and new political parties can spring up to tap public sentiment. Forces like the popular committees organizing to protect Egyptian neighborhoods from looters and the police could easily morph into a potent political force.

So ignore anyone who tries to paint the situation today in Egypt as a simple struggle between a moderate authoritarian regime led by Mubarak and a fanatical Muslim Brotherhood poised to lead Egypt into war with Israel. That regime, as it existed until last week, will be forever changed by the Days of Rage if it survives in some form or another under President Suleiman. Multiple unknowns surround a Muslim Brotherhood that has acted anything but radical in the last three decades, but that’s largely beside the point; the Brothers simply don’t have the numbers or the dynamism to take over this popular revolt. They’ll be a key stakeholder in any new order, but there’s no evidence to suggest they’ll play a dominant role. The military will still be there next month. So will the labor unions, and so will the privileged class that backed Mubarak’s regime and which in Egypt’s next iteration will still channel much of its economic and political power. Egypt’s history of secular nationalism will surely shape events, as will a surging popular will that until last week was almost entirely a mystery.

Brotherhood boycott?

Parliamentary elections are coming up this fall in Egypt, probably in October or November. But the opposition and ruling National Democratic Party alike have their eyes on presidential succession, assuming that President Hosni Mubarak, who is ill and has ruled for 29 years, probably won’t run again in 2011. In that light, the parliamentary elections have become part of the broader political jockeying.

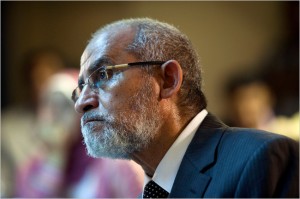

The Muslim Brotherhood commands by far and away the strongest street support among the opposition factions, but it’s a banned society whose parliamentary representatives are technically independents. Meanwhile, the secular opposition parties want to boycott the parliamentary elections to protest the ruling party’s heavy-handed manipulation of the voting process (since the last election, for instance, the government has cancelled the judiciary’s right to oversee polling stations). That’s the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide Mohammed Badie in the picture, getting yelled at by secular opposition leaders during an iftar.

The Brotherhood and the secular National Association for Change are circulating a petition calling on the government to amend the constitution and reform the voting process to allow free and fair elections. It’s a rare instance of the Islamist and secular opposition working together, but even in this arena they’re competing to show who’s stronger. The Brotherhood has collected nearly 700,000 signatures; the National Association for Change only 100,000. You can follow the dueling signature drives on the Brotherhood petition page and the NAC petition page.

You can also read more about the Brotherhood’s internal debate between seeking power and challenging it in my story today in The New York Times.

CAIRO — One by one, the guests at the Muslim Brotherhood’s annual Ramadan iftar banquet strode to the rostrum. A who’s who ofEgypt’s opposition began hectoring the Islamist group. The Brotherhood, they said, by far the most muscular and influential of Egypt’s dissident organizations, should withdraw from the coming parliamentary election that would most certainly be rigged by the authoritarian government.

“Why won’t you take the initiative?” shouted Karima El-Hefnawi, a secular activist and leader of the popular Kifaya protest movement. “Why won’t the Muslim Brotherhood boycott this farce?” The supreme guide of the Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie, sat uncomfortably a few feet to her right.

At the close of the evening, Mr. Badie was noncommittal. The Brotherhood, he said, in time would make up its mind: “Haste makes waste.”

The Muslim Brotherhood is engaged in a delicate dance. Despite all efforts to marginalize the Islamist organization by the United States and its close ally, the Egyptian government, it remains the most credible opposition group. Some of its members want the Brotherhood to fight the government head on, but the Islamist leadership has other goals: freedom to proselytize and organize in neighborhoods, and in the long term, a lifting of the official government ban on its activities.

With an end in sight to President Hosni Mubarak’s 29-year reign, the Brotherhood appears to be signaling its willingness to cut a deal with Mr. Mubarak’s potential successors by not overtly challenging the ruling party’s monopoly on power.