Egypt’s Sisi Is Getting Pretty Good … at Being a Dictator

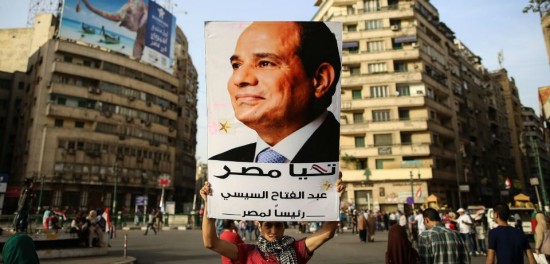

Photo credit: MOHAMED EL-SHAHED/AFP/Getty Images

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

The outrageous death sentences in Egypt over the weekend, and the muted reaction from Western governments, suggest that President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has cemented a ruling coalition that will propel him out of a transitional phase into a long-term project of power consolidation.

Lost amid the court ruling against more than 100 defendants — which include academics and senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood, even Egypt’s sole elected civilian president, Mohamed Morsi — is the mounting evidence that Sisi has cobbled together a workable formula for ruling Egypt. This formula might be doomed in the long run, but the long run can be very far off indeed.

Today’s governing agenda in Egypt centers around three things: a crackdown on “terror” and dissent, maintaining a steady flow of cash from the Sunni monarchies of the Gulf, and modest economic reforms that at a minimum give the impression of vision and positive momentum.

The government’s “war on terror” will resonate with Egyptians for quite some time. Jihadi attacks have proliferated since Morsi was deposed in July 2013; one fact sheet released by the government last year documented more than 700 people killed in the attacks. There have been dozens since, mostly targeting security forces and government facilities.

The public is repulsed by the bomb attacks on the police, army, and other government branches. Even most of the Muslim Brotherhood supporters of the deposed Morsi also condemn the insurgency and its terrorist tactics. As a unifying ideology for the Egyptian state, a war on terror might not suffice — but it will go a long way to mobilize what might be otherwise tepid support for Sisi and the military.

In prosecuting its war on terror, Egypt has lumped the Muslim Brotherhood together with the jihadi Ansar Beit al-Maqdis — equating dissent in the vernacular of political Islam with bombings and assassinations. “The Muslim Brotherhood is the parent organization of extreme ideology,” Sisi told the Washington Post in March. “They are the godfather of all terrorist organizations. They spread it all over the world.”

Perhaps Sisi is motivated by a sincere belief that the entire Islamist current is collectively responsible for the recent attacks, or perhaps he’s made a cynical calculation that the spate of violence offers an opportunity to eliminate the mainstream Islamist opposition under the cover of fighting an insurgency.

The battle against Islamists has given Sisi some legitimacy — but it isn’t what brought him to power. For that he counted on Gulf money, an initial precondition of the coup that toppled Morsi. As we’ve heard in great detail on leaked recordings from the office of Sisi’s chief of staff, the president made clear that he expected the billions to flow unabated from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies: “Man, they have money like rice,” a man who sounds like Sisi famously says in one of the leaks.

This might sound like thuggish extortion, but it’s also shrewd politics. Sisi recognizes that the Gulf can afford to underwrite Egypt, and that it’s willing to indefinitely pay $10 billion or more a year for a dependable ally in Cairo. Egypt struggles to import enough fuel and food staples to keep the country functioning and the poor quiescent; without Gulf money, the summertime power outages would likely turn into long-term blackouts and electricity rationing.

Egypt’s rulers have historically feared a “revolution of the hungry” if the circumstances decline for the nation’s many poor.

Economic reform, the last piece of the formula, is trickier. It’s become clear that Sisi’s autocratic ways and narrow, nepotistic circle of military advisors will preclude creative governance. But while significant reform is off the table, piecemeal improvements to the subsidy system could serve Sisi adequately for the medium-term. Meanwhile, theatrical flourishes like the $45-billion new capital planned for the desert outside of Cairo — a boondoggle for Emirati construction conglomerates which will probably never be built — and massive proposed public housing, irrigation, and road works projects give the impression of a nation on the move.

If even a small fraction of these projects materialize, Sisi will cement deep support in some quarters. Wealthy business owners and the small but politically influential middle class have both reliably remained in Sisi’s corner, and could benefit from infrastructure development. The military will also play a major role in any large-scale construction projects and, if shrewdly distributed, new housing or other perks could neutralize some of the few potential oases of organized political opposition, such as factory workers in the cities of the Suez Canal zone and the Nile Delta.

The medium-term stability of Sisi’s regime, however, may lead to more trouble for Egypt down the road. His repressive policies will not cure the country’s many ills, and are guaranteed to drive Egypt into even worse shape that it was when it rose up against Hosni Mubarak in January 2011. Recent events underscore Sisi’s paranoid style, punctuated over the weekend by banning soccer fan clubs known as Ultras and sentencing exiled political science professor Emad Shahin to death. As Shahin put it in a statement, the show trials are a centerpiece of Sisi’s effort “to reconstitute the security state and intimidate all opponents.”

The pattern of prosecutions fits that argument. If the government casts its net wide enough, it won’t have to worry about student union protests or critical university professors, because the majority of Egyptians will be frightened into silence.

Sisi’s paranoid style appears to be the product of a coherent view among Egypt’s fractious security services, which are showing a unity of purpose in carrying out the campaign against all political dissent. The military, police, intelligence agencies, and courts are pulling together to carry out the government’s political vision — an impressive bureaucratic achievement, but one that bodes poorly for democratic reform.

The downsides of the new dictatorship’s governing approach will be toxic for Egypt over the long haul. Securing the cooperation of a balkanized bureaucracy is not the same as controlling it: Sisi has the courts in lockstep on his side, but at the expense of their reputation. The courts have clearly abetted military rule, disbanding the elected parliament on flimsy pretexts, barring popular presidential candidates, and certifying election laws that served the military’s aims.

As a result of these machinations, no one will be able to take the judiciary seriously as a branch of government — and a future ruler, even an unelected autocrat, who wants to restore some semblance of the rule of law will face a daunting rebuilding job. The situation only deteriorated further today, with the appointment of Ahmed el-Zend as justice minister: The head of the influential “Judge’s Club” famously told a television show that judges “are masters in our homeland. Everyone else are slaves.”

The army, which paved Sisi’s path to power, remains the president’s only native constituency. But there’s no evidence to suggest that in a crisis — say, an economic collapse or a widespread popular uprising — Egypt’s generals would sacrifice their own institutional privileges to protect Sisi.

Even authoritarian rulers must play politics to retain power, pacifying the key organizations and constituencies that support them. Under the former dictator Hosni Mubarak, the military had to compete against the police, the intelligence services, and the circle of business moguls around the ruling family for its perks. Today, the military possesses unchecked power, which is likely to lead to greater corruption, unaccountability, and serial failures to accomplish the basic bread-and-butter business of the state.

This incompetence will negatively affect the very war on terror upon which Sisi is building his legitimacy. Jihadis are openly operating out of the Sinai, but according to the few independent reports that come out of the peninsula, poorly trained soldiers have employed scorched-earth tactics in retaliation, bombing towns and arresting random men while actual jihadis escape. Convicting and trying men for crimes theyprobably didn’t commit — as appeared to occur over the weekend in aballyhooed terror trial — won’t end the destabilizing domestic insurgency either.

Sisi also faces other long-term threats that are not solely of his making. These include an untenable national balance sheet, subsidies too expensive to maintain and too crucial to eliminate without massive social dislocation, growing unemployment, and inadequate water for agriculture under current usage practices.

Ultimately, any economic reform will depend on foreign pressure — a formula that didn’t work when the United States was the primary donor. Perhaps financial advisers from the United Arab Emirates will have better luck as they try to implement better practices in the ministries and government offices that will absorbed upward of $32 billion from the Gulf monarchies ever since Sisi’s coup. If those massive sums can’t buy meaningful political influence or instill sound economic practices, no amount of foreign money will.

The new regime is clearly unable to resolve these challenges, but history suggests that mismanagement can continue for a long time. Indeed, perhaps the greatest threat to Egypt is that Sisi simply muddles through. There are surely fissures within the regime, but he doesn’t need a monolithic ruling elite: He needs just enough power to stay in charge, and enough international support to ignore the outrage of Egyptians who want civil rights, political freedom, and genuine economic development.