The Middle East’s fading frontiers

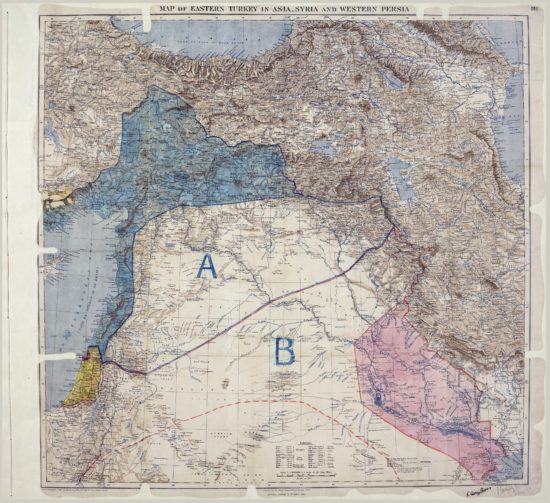

As the Sykes-Picot agreement turns 100, the borders it delineated are crumbling.

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

ONE OF THE Islamic State’s first gestures after conquering a vast portion of the Syrian and Iraqi deserts was to bulldoze the sand berm delineating the official border between the two states. In one of its first propaganda videos from the summer of 2014, “The end of Sykes-Picot,” a bearded fighter walks solemnly through an abandoned checkpoint in the former no-man’s land. “Inshallah this is not the first border we shall break,” the fighter declares in English.

Many Westerners taking their first notice of the toxic Al Qaeda offshoot were mystified: Wait, the end of what?

But the historical reference was not obscure in the Middle East, which for exactly a century has suffered the consequences of borders drawn by two diplomats who had orders from the top but weren’t considered the best informed Middle East experts in their respective governments — Sir Mark Sykes, an Englishman, and his French counterpart François Georges-Picot.

Since then, the Middle East has suffered a profound cognitive dissonance between the official state, often demarcated by unnaturally straight borders, and the human geography of how people live and who wields power in the lands stretching from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf. Indeed, the Sykes-Picot agreement has been blamed for many long-running catastrophes, from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to the violently thwarted national aspirations of many Kurds, Arabs, and other groups.

Yet for all the rancor, the Sykes-Picot borders are already crumbling. The orderly national borders they drew — mostly to please the interests not of the people who lived on the land but of colonial masters Britain and France — have been superseded, though not necessarily in the manner that anti-colonial critics would like.

SYKES AND PICOT’S era was roiled by the Great War, the deadliest conflict the globe had known until that time, and defined by American President Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic notion of self-determination. People across the world were supposedly going to be free to choose their own borders and shape their own nations.

That might have been the case in parts of Europe but not in the Middle East. More interested in destroying what remained of the Ottoman Empire and thwarting each other’s imperial aims, France and Britain agreed in secret on May 17, 1916, to carve up the region heedless of the human and political realities on the ground.

The Sykes-Picot agreement was leaked a few years after it was brokered. It enraged not only the people in the Middle East who had been promised self-determination but even experts in the British foreign office who had warned exactly against this sort of expedient and destabilizing imperialist border-drawing.

“All borders in the world are, in their own way, artificial,” says Joost Hiltermann, who runs the Middle East program for International Crisis Group and has written a book about the Kurds. He believes the instability in the Middle East today reflects pressure from groups like the Kurds and the Islamic State who feel the current state order doesn’t accommodate them. “Over time, sometimes a long time, the internal contradictions will explode the prevailing order,” Hiltermann said. “What the new order, or series of orders, will look like is anyone’s guess.”

Sykes-Picot has had a doubly poisonous legacy. First are the borders themselves, which have continually been contested by groups convinced they didn’t get a fair shake, from the Kurds and Palestinians to Shi’ite and Sunni desert tribes. Second is that they were dictated in secret by outsiders, forever enshrining the suspicion that schemers in Western capitals fiddle with the region’s maps, which of course, they did.

Kurds, who call themselves the world’s largest nation without a state, are planning an independence referendum this year. Some originally hoped to hold a vote on May 17, the Sykes-Picot centennial, to drive home the symbolic point that the old colonial order is dead.

It’s high time to take stock of the de facto new states operating in the Middle East and stop pretending that the Sykes-Picot borders are even in operation.

The Middle East is full of borders that don’t appear on official maps.

AGAINST THE ADVICE of many of their better informed colleagues, Sykes and Picot fashioned a new Middle East, literally drawing new nations out of whole cloth and truncating millennial aspirations for nationhood with a clumsy stroke through a map. Their map created the made-up new Kingdom of Jordan, which ended up displaced by the house of a twice-displaced monarch, the Sherif of Mecca, who had supported the British during the Great War and had originally been promised the throne of Syria. Wags of the day called the British approach to the state-building in the Middle East “everybody move over one.”

Lebanon was carved out of Syria. Mosul and Baghdad were cobbled into Iraq. Palestine was given to the British, who already had promised the territory to the Zionists. The biggest losers were the Kurds, a distinct ethnic and linguistic group who weren’t given a state at all. Today the Kurdish heartland stretches into corners of Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran.

British historian James Barr wrote a lively chronicle of the diplomacy of the Sykes-Picot era called “A Line in the Sand,” which is still wildly popular in Beirut bookshops five years after its publication. Barr unearthed secret British foreign office memos that correctly anticipated most of the terrible spillover from the Sykes-Picot agreement, including prescient predictions of the violence and instability that would follow the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine.

It is because of this history that even today random maps scribbled on napkins or published on blogs drive Middle East conspiracy theorists into a tizzy. After the United States occupied Iraq, many experts in the region were convinced that there was an official plan to divide Iraq into separate Shi’ite, Sunni, and Kurdish states. Comments in support of partition by long-retired US diplomat Peter Galbraith were cited as proof that a conspiracy was afoot. Similarly, after the Egyptian popular uprising in 2011, supporters of the deposed dictator believed they were actually the victim of an American-Israeli plot to cut up Egypt’s territory into smaller, more easily cowed mini-states.

It’s common to hear cosmopolitan analysts in the Middle East speak matter-of-factly about unknown, but in the common view, utterly plausible, secret plots to divide the region in the service of someone’s agenda: Iran, the United States, the Zionists, or some other culprit.

“The Sykes-Picot agreement was only revealed in 1917 after the Communists took power in Russia,” wrote Jamal Sanad Al Suwaidi, head of a think tank, the Emirates Centre for Strategic Studies and Research. “So the fact that there are no current plans that have been publicly announced by certain powers to divide the region does not mean that such plans do not exist — perhaps the details will become evident at a later time.”

It’s a version of that old saw: “Just because I’m paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get me.” There’s no arguing with the dirty facts of the secret map a century ago. It doesn’t help that Western powers have never stopped meddling even after the colonial era. The US invasion and occupation of Iraq are fresh in the region’s mind, as is the ongoing war in Syria with all its foreign sponsors and military advisers.

As a result, any chitchat about drawing new borders can instantly become a sensation. A map published by the Armed Forces Journal in the United States imagined what new borders would look like if they were redrawn by ethnic and sectarian group; it remains one of the publication’s top viewed articles even a decade later.

FOR ALL THE unwarranted conspiracy-mongering, however, a new Middle East is, in fact, taking shape — and it’s not the product of a map scribbled on a napkin by jolly Western agents (at least, not so far as we know!).

“This region, and Kurdistan in particular, was divided without regard to the will of its indigenous people, which in turn led to a hundred years of troubles, war, denial, and instability,” the president of the Kurdistan Regional Government, Masoud Barzani, said earlier this spring. Barzani has promised an independence referendum this year during the Sykes-Picot centennial. He presides over the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, which has functioned in most ways as an independent nation since the United States established a protectorate there in 1991 to shield Kurds from retribution by Saddam Hussein. Kurdistan has its own military and gas fields, but it still depends on the central government in Baghdad for revenue and trade.

Travelers who fly into Erbil, in Iraqi Kurdistan, don’t need visas from the central government in Baghdad. Kids growing up there are often educated in Kurdish and might learn English as a second language before studying any Arabic. While Kurdish officials are still organizing their referendum, a few weeks before the Sykes-Picot anniversary they announced the next best sign of sovereignty in the digital age: an Internet domain, “.krd,” which went online the first week of April.

“The same way that Scotland, Catalonia, and Quebec, and other places have the right to express their opinions about their destiny, Kurdistan, too, has the right, and it’s non-negotiable,” Barzani said.

His statelet is one of many Middle Eastern de facto nations you can find in the world but not yet on an official map or the list of member states at the United Nations.

Palestine was accorded “nonmember observer state” status at the United Nations in 2012, and its flag now flies over the UN headquarters in New York. On the ground, however, geography is even more complicated. Parts of the West Bank are supposedly under control of the Palestinian authority, but the land crossings are all controlled by Israel. Gaza has functioned as an effective state since 2005, when Israel withdrew its settlements. Access to the Gaza Strip is controlled entirely by outsiders — by Israel in the north and Egypt to the south — but inside, Hamas holds sway over a de facto city-state.

Rojava, a Kurdish-controlled statelet in northern Syria, declared official autonomy last month. Because of its precarious location on a strip of land bordering Turkey, which resolutely opposes its existence, Rojava might seem unsustainable. But the Kurdish party that controls it has managed to woo support from both the United States and Russia, for complicated reasons having to do with the war in Syria.

The Sinai peninsula, popular with sunbathing and scuba-diving tourists, was briefly occupied by Israel after its 1967 war with Egypt. It returned to Egyptian sovereignty in 1982 but arguably never to its full control. Today, the Sinai is an unruly place, with powerful tribal leaders and vibrant Al Qaeda and Islamic State franchises.

Hezbollah, the Party of God, is the single most powerful movement in Lebanon. It has its independent military, ministers, and members of Parliament in the Lebanese government, and wide swaths of territory that everyone in Lebanon recognizes are under Hezbollah control. Hezbollah polices sensitive areas, like borders and military training areas, sometimes in tandem with national authorities, sometimes on its own. The movement sees no interest in making the arrangement more formal; power on the ground serves it better than any official designation.

One shorthand for figuring out the real borders is to ask who could protect you effectively if you were traveling in a certain area. If the answer is “no one,” you could be talking about an area of failed governance like Sinai, or a contested border zone like the front lines between the Islamic State, the Free Syrian Army, and the Syrian government.

If, on the other hand, the answer is some entity that’s not the official government, then you’re probably looking at one of the post-modern, post-Sykes-Picot regions that has emerged heedless of the rule-making of cartographers and international bureaucrats — like Hezbollah, the Islamic State, or Hamas in Gaza.

In fact, one of the most interesting developments a hundred years after Sykes-Picot is that many of the most dynamic, independent groups in the Middle East are accommodating their thirst for autonomy without any redrawing of official borders. The Kurds in Rojava are careful to describe their regional government as part of a federated Syria, and even the vociferous Barzani, in Iraqi Kurdistan, has made clear that even after a referendum he wouldn’t formally declare independence unless neighboring countries supported the move, which they are unlikely to do.

Hiltermann, who has followed the twists and turns in the Middle East for more than three decades, says it’s unwise to make predictions: “All we know is that what used to be will not return in exactly the same form. It might even look radically different: a brave new world.”

The maneuvering of groups who don’t fit neatly into the existing nation-states suggests that the map of the Middle East is already been redrawn. This is how sovereignty changes today: through human geography — or bulldozers — which changes not maps, but facts on the ground.