Wayback Machine: Designing a new Egypt

Khalil Hamra/AP photo

Back in the spring of 2011, the vistas of possibility lay wide open. What kind of new government would Egyptians decide after they shocked the body politic out of its stupor with their history-defying revolution?

Today’s post-Tahrir system hasn’t reinvented anything; it’s more like the old butcher shop with sharpened knives and a more expensive burglar alarm. But that moment isn’t that far distant when Egyptians were empowered to draw the blueprint of a completely new system. Remembering the ideas that percolated then reminds us that the prospect for something different has not been foreclosed, despite the status quo today.

For today’s installment of the Wayback Machine, I offer this story I filed almost four years ago and which I came across while organizing my files for New Year’s.

* * *

Now what?

The next version of Egypt could set an example for the Arab world. Inside the struggle to imagine a new state.

May 29, 2011

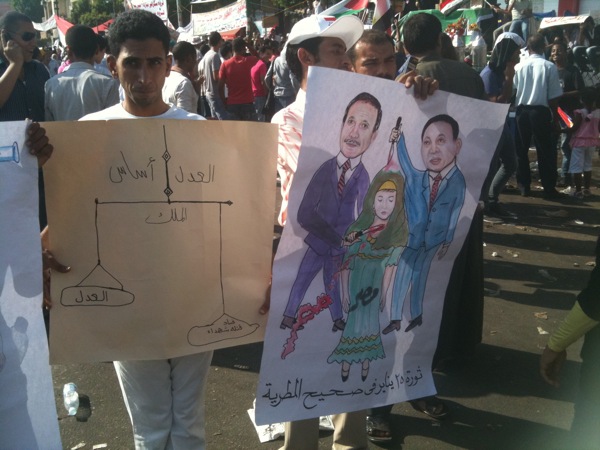

CAIRO — Traffic stopped in Tahrir Square during the revolution, but four months later, the torrent of marching humans that briefly made Cairo a world symbol of the thirst for justice has been replaced by the familiar, endless stream of grumbling cars.

The tricolor paint on the city’s trees, applied with gusto in the immediate weeks after President Hosni Mubarak resigned, has already begun to fade. As the wilting heat approaches its summertime averages in the 90s, vendors here do a brisk business selling “I [heart] Egypt” T-shirts, mock license plates commemorating the date of the uprising, and posters of the young martyrs to Mubarak’s security forces.

Schools have reopened; births and deaths are once again registered by Egypt’s ubiquitous bureaucracy; and the machinery of state continues to deliver the basic services that make this nation of 80 million function. The military junta that replaced Mubarak polices the streets and censors the media, though with a touch slightly lighter than Mubarak’s. There are still street demonstrations; on most Fridays, small factions chant in Tahrir Square and distribute leaflets demanding to put figures of the old regime on trial, fix the broken economy, or allow greater freedom to criticize the government.

Most of the nation’s energy, however, has shifted to a new debate: what should come next. Egyptians are realizing that they now face a challenge perhaps even more historic than its revolution. They need to design, nearly from scratch, a legitimate state to govern the most populous Arab nation in the world.

Egyptians are supposed to write a new constitution sometime this fall. And although no one is sure precisely how this will occur — the schedule is controlled by the military junta, which communicates chiefly through updates on its Facebook page — the public conversation has already metamorphosed into raging debate over what the government should look like. The outpouring of public frustration that reached a crescendo

in Tahrir Square on Feb. 11 has now moved onto a crowded lineup of television talk shows and the cafes. As youth activist Ahmed Maher put it over a demitasse at the Coffee Bean this week: “Before the revolution, everyone talked about soccer and drugs. Now they talk only about politics.”

Emboldened newspapers obstreperously editorialize about the path toward democratic elections. On TV, academics, activists, and cultural personalities wax about the best structure for a future Egyptian state. Once-submissive veteran politicians now rail in public meetings against “counter-revolutionary” officials sympathetic to the old regime.

The task they face is enormous. Like most of the Arab world, Egypt’s entire post-colonial experience of government has been authoritarian: first a monarchy, and then nearly 60 years of rule by three military dictators in a row. And there’s simply no road map available: no example of another government in the region that reflects the aspirations of its population and rules by consent rather than through a police state.

Over the last three months, the debate over Egypt’s future has taken shape as a tug-of-war among a few big visions. Should Egypt have a broad but weak state, one that touches people’s lives pervasively but with power diluted to prevent the rise of another strongman? Or should it deliberately rely on the country’s most powerful institution, the military, to guide the state, as Turkey did during its recent rise? A libertarian school seeks a minimalist constitution, more like America’s, and a vastly downsized state that rethinks the old corporatist model; and a cohort of nationalists want to start revitalizing Egypt by turning outward, forging partnerships with Turkey and Iran to give Egypt a foundation in a new regional power structure.

In the last century, Egypt led the rest of the Arab world in throwing off colonialism, in embracing the excesses of Arab nationalism, and then to a cold peace with Israel and a long spell of provincial stagnation. Today, as Egypt struggles to formulate a vision for what will come next, its people are well aware that at stake is not only their own future, but also a potential new model for what an Arab state can be.

The question of what a new Egypt should be might seem impossibly large, but Egyptians agree on a few broad principles: a sovereign state, not dependent on foreign largesse, and not ruled by cult of personality. Whatever comes next might borrow from Western models, but primarily will draw on Arab views of justice, popular sovereignty, social harmony, and consensus. That starting point still leaves gaping room for uncertainty.

“This is like reinventing the wheel,” groused an elderly lawyer at an early national brainstorming session for a new constitution.

“It’s exactly what we should be doing,” snapped back Tahani El Gebali, the first woman judge on the Egyptian Supreme Constitutional Court, and a prominent voice in the debate over Egypt’s future.

There aren’t many helpful examples. The modern Arab world has only seen glimmers of viable, democratically accountable states: Iraq, briefly in the 1970s before it became Saddam Hussein’s fiefdom; Egypt itself, in moments when its economy was growing and it could project military power in the region. For the most part, however, the region has been plagued by one-man misrule, historically propped up by Cold War-legacy superpower giveaways.

Most of the elites arguing over the smartest path to Egyptian democracy agree that first will come a parlous adjustment period. Gebali and other liberalizers talk a lot about “democratic literacy,” arguing that it will take years to teach the Egyptian public about its rights in a genuinely representative system. Authoritarians and others sympathetic to the status quo phrase it differently: They argue that Egyptians “aren’t ready” for an open political system and that representative democracy would yield only chaos.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given Egypt’s recent history, the strongest group of democracy advocates is arguing for a system designed to have a weak president and multiple checks on state authority. By their logic, it’s less important to have a streamlined and highly effective state than it is to thwart the next aspiring Mubarak. Egypt, for all its problems, has the luxury of coherent, functional institutions — it’s neither a failed state nor a crumbling one. Therefore it can afford a transitional phase with a fractious government whose main purpose is to liberalize the state and instill the notion of popular sovereignty.

“We always have had one man ruling alone,” Gebali explained in an interview. “Now we need alternate centers of power.”

Egypt has a well-developed liberal intelligentsia, and some of its most established legal scholars have embraced this approach. Their notion, broadly speaking, is to build on the ideas of revolutionary America and France, but to separate powers even further — by their reckoning, a US-style presidential system is also vulnerable to dictatorial impulses. Their proposals incorporate many ideas unique to Egypt and which speak to the Arab Spring’s particular blend of concerns — not just for democracy, but for social justice, transparency, and economic progress led by the state, rather than by free markets. So they don’t talk of abolishing the considerable and costly subsidies that keep food and fuel affordable to Egyptians, nearly a quarter of whom live below the poverty line. The education and health care systems are rife with failure, but the consensus holds that the central government should be responsible for fixing them. And though the economy is moribund, virtually all Egyptian political players support a heavy state role in setting wages and employment terms.

Within the wider liberal community runs a small strain of what might be called libertarian minimalism: thinkers who share the same views about rights and civil authority, but who want to see Egypt’s vast state seriously downsized. Many economists and government technocrats see their bloated state policies as costly and unsustainable, but are loath to say so in public. (Understandably so: The vast majority of Egyptians like these state subsidies and entitlements.) They want to undo the philosophical and legal clutter caused by decades of inept governance.

“We need a very short constitution,” said Ibrahim Darwish, an American-trained expert in constitutional law. “The US Constitution has only seven articles and has lasted two and half centuries.” His position carries moral authority — Darwish helped draft Egypt’s 1971 constitution, and is currently advising the Turkish government on its new constitution — but he admits it is unlikely to get much of a hearing among Egyptians, even liberals, because of their deep attachment to complex state structures and legal regimes.

Another broad line of thinking in the debate, one associated with traditionalists rather than liberal modernizers, emphasizes Egypt’s existing strengths, its military establishment and historic regional clout.

A school that might be called neo-nationalists is pushing for Egypt to reform itself first by cultivating international power. In their view, Egypt has atrophied as a country because it has spent decades subserviently implementing the foreign policy agendas of the United States and Israel. The key to Egypt’s future, by this thinking, lies less in its form of government than in shoring up its position in the world.

The foreign policy school argues that Egypt can join Iran and Turkey to form a “triangle of power.” The Egyptian writer and analyst Fahmy Howeidy has even visited Tehran to promote the idea that a coordinated foreign policy by the three regional powers could change the balance of power between Israelis and Palestinians, and curtail American influence in the region.

For these thinkers, the past few months have been galvanizing: Egypt’s first post-revolution foreign minister, a career diplomat named Nabil Al-Araby, quickly shook up the Arab world’s arithmetic by brokering an agreement between Fatah and Hamas, signaling that Israel would get a more skeptical hearing in Cairo, and irritating the oil-rich monarchies of the Persian Gulf by vowing to “open a new page” of warm relations with Iran. Like many of the exponents of this school, Al-Araby comes from a ruling party background inspired by the example of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s leadership and the ideology of Arab nationalism, which propelled Egypt onto the global stage from the 1950s until the 1970s.

The final important school of thought in Egypt’s state-building wars is the status quo militarists. In their view, Egypt has functioned as a security state for almost the entirety of its post-colonial history, and the military — as guardians of the state and of the people — is the only institution suited to transition Egypt into a new age. They point to the example of Turkey, where for most of the past 50 years the military has repeatedly checked what it saw as the excesses of elected governments by stepping in and temporarily taking power. Although it sounds like anathema in Western politics, Turkey has enjoyed a long-term stability rare in the region, culminating in a renaissance of civilian authority over the last decade.

In Egypt, it’s not only self-interested military officers who turn to the Turkish model. Many secular Egyptians, along with the country’s Christian minority, fear that electoral democracy would empower Islamic fundamentalists, and see the military as guarantor of a secular state. Even after the current junta yields to a new constitution, many of the military’s supporters would like to see a permanent role for it as a sort of trustee for the essence of Egypt.

Such trust in the military worries academics who’ve studied other nations making the transition from dictatorship to democracy; in places like Latin America and Asia, clear subordination of the military to civilian control has proved a necessary step to a stable modern state. But the popularity of this view in Egypt makes it a serious possibility.

For all the high philosophy at its heart, the constitutional debate in Egypt is unmistakably a proxy for the domestic power struggle afoot between the still-ruling military establishment and the liberals who want to build in Egypt, for the first time, a truly civilian state. Abstract terms like revolution and counter-revolution translate into very concrete positions — a military junta cut off at the knees, or a reconstituted deep state in which the military ultimately steers the government.

But in its sense of potential, the Egyptian conversation today also suggests a little bit of what it must have felt like in America in the age of the Federalist Papers. In revolutionary America, the founders self-consciously thought about the global implications of their effort to forge the first state built on Enlightenment ideals. Similarly, Egyptians are aware they have embarked on a project that could fashion a new social compact for the Arab world and beyond.

That ambition is evident in the small ideas also percolating through the society, as people reconsider issues from the role of religion in society and the philosophical origins of law, the rights of women and minorities, to uniquely Egyptian institutions like the half of all seats in parliament reserved for the peasantry.

On the current timetable, Egyptians are scheduled to vote for a new parliament in September, which will in turn choose the drafters of the next constitution. If all goes according to this plan, by the end of the year Egypt will have a new president and a new constitution. All this could change, of course, with a single pronouncement from the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.

At the Coffee Bean last week, members of Maher’s April 6 movement — one of the pivotal activist groups that sparked the January uprising — strategized for the year ahead. They argued about the right mix of presidential and parliamentary authority for Egypt, and how to market political engagement through the bread-and-butter questions of economic survival that most concern the average Egyptian. Dozens of similar meetings of every conceivable stripe, from reactionary monarchists to anarcho-syndicalist, take place every night across a country that finds itself at the exact midpoint between the opening act of its revolution and what might be the first truly fair elections in its history.

“The situation in our country is critical,” Maher said quietly. “This transition will take at least two or three years. It will be a long time before we will have a stable form of government that we can trust.”

Down but not out: Egypt’s revolutionary youth

Egyptian youths shout slogans against the country’s ruling military council during a demonstration in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt, Nov. 30, 2011 (AP photo by Bela Szandelszky).

Egyptian youths shout slogans against the country’s ruling military council during a demonstration in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt, Nov. 30, 2011 (AP photo by Bela Szandelszky).Young people and youthful energy propelled the Arab uprisings that began in 2010. And while the cohesion and impact of vaguely defined “youth” movements have been overstated, they remain the most important potential source of change—the Arab world’s best hope. The small vanguard that drove the original uprisings is growing more organized and more ideologically sophisticated even as, for the time being, it has lost political ground.

Egypt has always set regional trends in political thought. Its Tahrir Square uprising raised expectations for democratic transitions throughout the region, although the other Arab revolts brought wildly divergent results, especially for youth. Today the military appears to have won in Egypt, but the long-term outcome of the struggle there between revolutionary and reactionary forces is still in question; how it unfolds will be a bellwether for the Arab world.

Youth Is a State of Mind

Basem Kamel makes an unlikely revolutionary youth activist. I first met him four years ago, inside the small tent erected by the Revolutionary Youth Coalition to house its big-tent deliberations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. He seemed decidedly middle-aged and established: balding, evenly shaved despite his sleep-deprived gaze, slightly stooped, his scruffy protest clothes accented with a knotted orange scarf. He was 41, father to three children, proprietor of an architecture firm. “Youth is a state of mind,” he laughed when I arched my eyebrows at his age.

But like the Revolutionary Youth Coalition and the fractious panoply of movements for which it briefly served as the umbrella, Kamel represented a radical challenge to the status quo. Against the mores of the ruling party, Kamel appeared young, pluralistic, open-minded, radically experimental and egalitarian. So were the other “revolutionary youth” I encountered in Tahrir Square, ranging in age from children to grandparents.

Kamel had gone within a year from apolitical observer to revolutionary policy wonk. He wanted to throw out the entire regime’s way of doing business along with then-President Hosni Mubarak. He wanted a rules-based social welfare state that encouraged entrepreneurship and initiative while efficiently taking care of the poor and vulnerable. He wanted justice for Egyptian citizens who had been abused by police and military personnel, and he wanted to see his fellow citizens learn to take responsibility for everything from litter to voting. “If we succeed, everything will have to change,” he said then. “It will take a long time.”

The Revolutionary Youth Coalition is no more. It collapsed a year and a half after its founding, because its secular and Islamist members lost trust in each other. It was the sole institution in Egypt that tried systematically to bridge the gap between Islamist and secular political actors. Elsewhere in the Arab world, only Tunisia’s Parliament has attempted the same feat, with equivocal success.

Yet despite its noble aims, the coalition also embodied the region’s political identity crisis in its very name. “Youth” and “revolution” are virtually meaningless as explanatory categories for what is taking place in Egypt and elsewhere across the Middle East. The Arab world today is in the grip of a regional struggle for control—and in some cases a fundamental redesign of government—being waged among many contesting visions: hereditary monarchs, old-fashioned nationalist states, incremental Islamists, nihilist jihadists, socialist reformers, anarchists and others. The young can be found in almost every one of these locales and movements, including the most reactionary establishment political parties and statist institutions. Similarly, some of the most creative and constructive political forces feature middle-aged or even old activists in inspiring roles.

The particular problems facing youth as demographically defined—completing secondary or higher education, finding a first job or career and establishing a family—are economic and social. And while young people have a special kind of energy that dissipates with age, none of these factors predispose the young toward any particular political tendency. Throughout the Arab region, as throughout the rest of the world, they are just as likely to be apathetic as political, or reformist as conservative.

Nevertheless, a set of new political ideas and processes has been unleashed in the Arab revolts. The energy of young street protesters catalyzed a moment of revolutionary potential, a moment that shattered the assumption of regime staying power and opened the way for competitive politics and new ideologies. That fundamental idea—that a peaceful popular movement can replace a repressive state with a responsive, democratic, just and egalitarian polity—has survived today in a battered condition.

In Egypt, the country with the greatest potential and the greatest political impact on other Arab countries, the idea of change survives mainly in the beleaguered family of “revolutionary youth” movements, for which the country’s broken political system has made no room. The story is different elsewhere. Tunisia, for instance, has a plethora of young activists but no predominant set of youth movements, most likely because the existing political structure, with its parties and trade unions, engaged in meaningful negotiation that was able to harness the energy of young revolutionaries and channel it into a successful transition to democracy. Lebanon offers a third alternative—a paralyzed dysfunctional state where established sectarian parties have managed to absorb and dissipate youthful energy and momentum for reform, without making any improvements in governance or way of life.

A close and honest look at the condition of the Arab youth movements tells us a great deal about the prospect for systemic change in the region. At the core of the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia was a group of movements that espoused an agenda much more about revolution than about youth. Its supporters were concerned with political and economic injustice, and they touted democracy in a local vernacular, refusing the notion that it is a tainted or premature import from the west.

The revolutionary youth have been roundly defeated in Egypt. Tunisia’s more successful uprising has subsumed most of its youth activists into mainstream parties, perhaps a sign that political life is healthy or diverse enough not to require a binary external category such as youth to advocate for reform. Elsewhere, youth movements have remained marginal, as in Lebanon, or been sidelined by violence, as in Syria, Libya and Yemen.

But there is a clear and admirable agenda, one quite threatening to the region’s status quo regimes, articulated under the banner of revolutionary youth. Any Arab state that doesn’t grapple with its central claims and aspirations will remain fundamentally insecure, under threat any time circumstances conspire to make an opening for the latent uprising incubating in the warmth of their misrule.

The Bulge

The Arab world is disproportionately young; more than half of the population is under 25. Education systems are failing. Young people make up almost all the new entrants to the labor market, and the Arab region leads the world in youth unemploymentaccording to the United Nations. Demographers and economists who look at the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have rightly called attention to the youth bulge, including a looming one in Egypt, coupled with the region-wide systemic failures to educate citizens and provide them jobs.

The considerable scholarship about the demographic and economic implications of the youth bulge explains one of the many dispiriting constraints on growth and quality of life in the MENA region. A recent United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) paper summarizes the reams of demographic and economic analysis of the Arab youth imbroglio: “Without noticeable improvements in their economies or employment prospects, especially for much of the frustrated youth, rising demonstrations, unrest and violence appear unavoidable for the nearly half a billion people in the Arab world by 2025.”

But “demographic destiny” and the depressing economic conundrums of the Arab economies tell us nothing about the likelihood of political explosions, transitions or repression. Poor states that have little concern with the rights and welfare of their citizens can still perform at dramatically different points along a spectrum from murderous and self-destructive, like Syria; to aggressively indifferent, like Egypt; to muddling but occasionally passable, like Jordan. Regimes with massive youth bulges can successfully crush dissent, as Iran did to the uprising known as the “Green Revolution” in 2009, or escape it altogether with minor adjustments, as Saudi Arabia has done since the Arab uprisings. Demographics are not destiny, politically speaking.

Egypt’s Movement Youth

The past two years have brought a crescendo of terrible news for supporters of pluralism, rights and democracy in Egypt. The country’s first and only elected civilian president, Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, ruled erratically and eroded civil freedoms. He was deposed in a popularly acclaimed coup in July 2013.

Reflecting the general patterns of society, an apparent majority of young people, including many activists, supported the anti-Morsi Tammarod protests. Only a tiny number of them immediately criticized the military’s direct takeover of power, although dissent quickened after the military regime massacred at least 1,150 Morsi supporters in Cairo’s Rabaa Square on Aug. 14. Egypt’s new leader, Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, swiftly moved to outlaw protest and ban the Muslim Brotherhood, and over time has arrested almost all the leading dissidents across the political spectrum. He has restored and intensified the repressive methods of the old regime and has banned critical figures from appearing in the media.

In one sense, the playing field looks like it did under Mubarak: A state behemoth that is terrible at governance uses a heavy hand to crush opposition, and faces a very small but committed activist community that includes old veterans and youthful newcomers.

But Sissi, a general who resigned from the military when he decided to seek the presidency almost a year after his coup, may face open revolt much earlier in his tenure than Mubarak, unless he indefinitely maintains his unprecedented levels of violent suppression. The generation of activists that propelled Tahrir has gone on to establish political parties, youth movements and other institutions. Its ranks have gained invaluable organizational experience. They have built vast interpersonal networks, bound by the shared experience of torture, detention, long prison sentences, exile and mourning. The brightest of the revolutionary leaders and movements have slowly begun to address their biggest failings; they are creating clearer, more compelling alternative ideas of governance, and they are developing strategies that take into account the volatility of mass public opinion.

Moreover, a significant portion of the socially conservative elite—the centrists who leaned slightly toward the revolution in 2011 and toward Sissi in 2013—has experienced political mobilization and the sense of power that comes with overthrowing a regime. Egyptians have acquired a taste for political empowerment and accountability.

A survey of the current state of the activist youth movements, as well as the widespread apathy among the youth demographic, can invite depression. Yet it is remarkable, especially when compared with the period before 2011, that in the face of historically unprecedented violent repression of all dissenters, from human rights lawyers to Muslim Brothers to bourgeois middle-aged civil society activists, a wide array of movements has persisted in opposition to the state.

Public opinion has gone into a version of political hibernation. Protests against Sissi’s government are small, and polls suggest transition fatigue. Some individuals who casually participated in protests or politics from 2011-2013 told me they had “lost faith in politicians,” “no longer trusted activists,” or were “ready for stability so I can get a job and have my life back.”

However, among the most dedicated activists, only a few have defected from politics entirely, while many have made notable shifts. Top among them are the organized revolutionary youth who have shifted allegiance entirely, best represented by the anti-Morsi Tammarod movement. Its original founders were five youth activists, including veterans from the April 6 Youth Movement and from former presidential candidate Ayman Nour’s Ghad (Tomorrow) Party. They mobilized a signature campaign against Morsi, and after the coup they became stalwart cheerleaders for Sissi’s elevation from junta leader to elected president. Tammarod is undeniably a reactionary force that has benefited at times from state support, but it is also undeniably a youth movement toward which Sissi’s government has turned a jaded eye.

Basem Kamel, the 41-year-old revolutionary “youth” I met in Tahrir four years ago, went on to co-found the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, which has now positioned itself to the right of its revolutionary roots as a traditional liberal party. He became one of just a handful of revolutionaries elected to the short-lived parliament of 2012. After the Sissi coup, Kamel and his party supported Sissi’s transitional government, prioritizing secularism and a fight against the Muslim Brotherhood over opposition to military rule. “I didn’t support Sissi, I opposed Morsi,” he told me this winter. “Whatever we are now, it is better than the Muslim Brotherhood.” He now sounds like a cautious reformer rather than a principled revolutionary.

Kamel opposes Sissi’s crackdown on protest and free speech, but he believes it will take years or decades for vanguard activists to convince the Egyptian public to support a genuine move away from military rule. He has chosen to work within a political party that has been allowed to continue operating by the regime as part of a trusted or permitted opposition.

Youth and revolutionary politics continue to exist, despite the crackdown under Sissi, because of systemic state failures. Police still torture with impunity; runaway judges make a mockery of the rule of law; army officers control political life; and the economy continues to fail the vast majority of its citizens, while a corrupt elite connected to the army and a ruling clique rakes in rentier profits.

And the most visible independent activists have continued to agitate, demonstrate or write treatises even from prison. Alaa Abdel Fattah, an independent leftist who helped form a revolutionary coalition after the Rabaa massacre, has produced a powerful oeuvre from his jail cell. Most recently, this fall he spurred a wave of partial hunger strikes under the slogan “We’re fed up.”

Meanwhile, the April 6 Youth Movement, a grassroots movement that has made deep inroads among working-class Egyptians, has survived a concerted effort by the state to dismantle it, in part because the movement’s leaders and members have in fact collaborated with right-leaning nationalists. These positions drew enmity to the movement, but they also put it more closely in step with the Egyptian mainstream. Perhaps for this reason, April 6’s grassroots network has survived the imprisonment of its leadership. As recently as November, it was able to muster a sizable protest in Tahrir Square, along with other secular, non-Islamist revolutionary groups angered by a judicial verdict clearing Mubarak of further charges.

Egypt’s Islamist Revolutionaries

The final locus of continuing resistance activity in Egypt comes from the Islamist space. Always the largest, most organized and best-funded opposition to the state, Islamist groups have always had formidable youth wings. During the revolutionary period, the Islamist political space fragmented. Today it still includes the largest number of active opponents to the Egyptian regime, although many of those activists are young Muslim Brotherhood members calling for Morsi’s reinstatement. They are increasingly isolated not only by the state, but from revolutionary movements who view Morsi’s autocratic tenure as a betrayal.

Yet a principled group of former Muslim Brotherhood members forms one of the most interesting revolutionary cohorts. Hundreds of young men and women who were among the elite of the Brotherhood’s official youth movement defied their hierarchical organization bosses and took part in the original Jan. 25 uprising in 2011. Most of them believed the Brotherhood should stay out of politics and remain a social and religious organization. These were pious and committed Islamic youth who believed in a secular, pluralistic state. Three of them were founding members of the Revolutionary Youth Coalition; they were among the first Brotherhood youth officially expelled by the hierarchical Islamist group.

They founded a political party, the Egyptian Current, which failed to attract wide membership. Some of its members work as independent activists or have joined secular political parties. Many of its best-known leaders now work with Strong Egypt, the political party of an ex-Muslim Brotherhood leader and presidential candidate, Abdel Monem Aboul Fotouh. Strong Egypt has been one of the only political organizations to condemn authoritarianism quickly and consistently, whether practiced by liberal civilian politicians, Morsi or Sissi. It forms the only existing bridge between secular revolutionaries and the powerful Islamist bloc, which for now has distanced itself from a project of pluralism, reform or revolt.

But the distrust between the two camps runs too deep for the kind of cooperation it would take to effect meaningful change in Egypt, and continuing efforts to mediate between anti-regime revolutionaries and Islamists have failed so far. Moaz Abdel Kareem, a former Brother and Revolutionary Youth Coalition member, has been one of the most persistent advocates of secular-Islamist collaboration. “It is crazy to think we can have a revolution without the Islamists,” he told me recently over a water pipe in a cafe in Istanbul. “We need to start a dialogue and agree on things we can fight for.” His own predicament suggests the impossibility of unity now; his old Islamist colleagues reject him as far too secular, while his revolutionary colleagues suspect he’s still secretly a Muslim Brother.

Illustrating the divide, in late November, secular revolutionaries rebuffed a public call from the Brotherhood for “revolutionary unity.” An April 6 spokesperson told Mada Masr, an independent Egyptian publication, that his organization would never again trust the Islamists, while a member of Strong Egypt said it was waiting for the Brotherhood to revise it positions and prove it could “keep its word.” In a further illustration of the exclusion of political “youth” dynamism by established political players, the Muslim Brotherhood itself criticized its own young members for going too far in their efforts to forge a united front with secular activists. The Brotherhood’s paternalistic tone echoes that of first Mubarak and now Sissi, with its patronizing dismissal of youth politics as naive, subversive or outright traitorous.

Sissi is unlikely to address Egypt’s core failures: the collapsing economy, the utter lack of justice or rule of law and the smothering of political life. In Tahrir Square in 2011, many people told me they had finally been motivated to protest because the state “humiliated” them: It prevented them from supporting their families, and it didn’t allow them the slightest political voice. The implication is clear. A regime might be able to get away with corruption and misrule if it allows some democratic expression, or it might get away with oppression as long as it delivers basic quality of life. But it will have trouble keeping its population quiescent if it fails on both counts.

The Role of Youth Beyond Egypt

Beyond Egypt, the entire Arab state system has been called into question, which is why powerful vested interests from the Gulf monarchies to the region’s nationalist militaries have engaged so fully in what they rightly view as an existential struggle. Nearly every country in the region has responded to these profound forces, although it is still early in their historical lifespan. Each Arab state offers a model of how to crush, harness or coopt revolutionary energy.

Short of war, there are three general approaches. The first is to deploy a police state to marginalize revolutionary ideas; Egypt is the leading example, but Bahrain and to some extent Jordan have followed a similar approach. The second is to embrace revolutionary energy within the system and attempt a transition: Tunisia has done this most successfully, although at periods Yemen and Libya seemed to have managed some degree of systemic change. The third is to redirect or absorb the revolutionary energy with neither a frontal clash nor a sincere effort to respond to its demands: Lebanon is the quintessential master of this sort of twisted jujitsu approach, although its principles can be seen at work in the maneuvers of regimes in Morocco, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. A closer look at Tunisia and Lebanon, as alternatives to Egypt’s course, also highlights the problem with relying on youth as an organizing principle to explain Arab politics.

Tunisia, Model or Exception?

Increasingly, Tunisia seems like an outlier in the Arab world. Its peaceful uprising was disproportionately younger than Egypt’s, and it was quickly supported by key institutional players, including the military. The biggest political blocs, the Muslim Brothers and the secular trade unionists, managed to negotiate a consensual constitution and a balanced transitional government despite their divergent visions. Islamists voluntarily ceded power after losing in Tunisia’s second elections. Not everyone is satisfied, but none of the key constituencies profess to have been locked out of the political transition, in contrast to Egypt. Perhaps most important in the context of the current discussion is the fact that “youth” were not ghettoized, but rather dispersed across the spectrum of politics and civil society.

Tunisia is a small nation whose relative wealth and education levels make it hard to compare to other Arab countries. Yet activists elsewhere in the region have drawn some key lessons. Tunisia benefited from a balance of power that included trade unions with a sizable, organized following, and also from a wise provision in the transitional electoral system preventing the winning party from amassing an absolute parliamentary majority. The main parties engaged in sincere, if occasionally acrimonious, negotiations. Islamists repudiated violence committed by their supporters, while secularists have avoided the taint of military authoritarianism that has come to characterize so many of their Egyptian counterparts.

This is perhaps a result of the fact that, while in exile years before Tunisia’s uprising, Muslim Brotherhood leader Rachid Ghannouchi and liberal dissident Moncef Marzouki met regularly, despite their profound ideological differences. Their relationship produced a level of institutional trust during Tunisia’s initial transition period, when Marzouki was president and Ghannouchi’s party controlled the government.

The Lebanese Alternative

For better and often for worse, Lebanon’s muddle-through system of compromise and patronage has become a regional model. Once dismissed as dysfunctional and corrupt, Lebanon’s solution to its 1975-1991 civil war has come to be seen by many other regional actors as a lesser evil, often worth emulating. Iraq might have accelerated the path to sectarian civil war by adopting a Lebanon-style sectarian ethnic quota system, but many there still see “Lebanonization” as a palliative and a preferable alternative to a bloodbath. Syrian activists who in 2011 swore they would never be “another Lebanon” now tell me that ending up like Lebanon after a decade of fighting might be the best hope they’ve got.

Lebanon’s volatile stalemate has staved off civil war and internal political revolt despite myriad systemic failures to address the concerns of ordinary citizens, especially unemployed or underemployed youth. In this, Lebanon might once again suggest a somewhat distasteful workaround.

Interestingly, no substantive youth or revolutionary or reform movement has emerged in Lebanon since the Arab Spring uprisings. Polling and anecdotal evidence suggest that the majority of Lebanese resent the spoils system of governance, controlled by the same major warlords who have dominated politics since the civil war. Yet their economic energy has been dissipated, either absorbed into the corrupt spoils system at home or dispersed into Lebanon’s vast diaspora, the proceeds from which prop up the country’s crippled economy.

Youth are freer in Lebanon than anywhere else in the Arab world to engage in cultural activity, although state security censors still carefully police the boundaries of free expression to silence radical critiques of the power structure. But that freedom doesn’t extend to politics. Young Lebanese are free to harness their political energy into the vibrant youth wings of the existing political parties, but not to challenge the status quo. All the major factions have intricate institutions to tap into youthful energy, including scouts, paramilitaries, social clubs, student council elections, fundraising work and ultimately party membership. Opportunities for political participation are limited to the existing sectarian parties.

One exception is the on-again, off-again movement in support of civil marriage, which remains elite, small and, while threatening to the sectarian spoils system, neither radically revolutionary nor inherently political. Presently, the civil marriage cause appears dormant. In times of heightened security fears, the demands of civil society in Lebanon tend to be drowned out, although a dedicated core group of civil society activists has persisted in the face of decades of pressure and ups and downs.

Conclusion

The political movements that challenged the Arab world’s established order in 2010 and 2011 are still in the process of developing. Their ideas and platforms are inchoate, and their leaders and core members are often under attack. In multiple countries, including Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Bahrain, proponents of even nonviolent incremental reform have been subject to terrifying levels of state violence. Elsewhere they have been systematically but less bloodily silenced or co-opted, including in Jordan, Qatar, the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

But it seems obvious that these movements are not going away, just as the Muslim Brotherhood, with its compelling ideology and disciplined organization, has never disappeared—despite repeated attempts at state-sponsored eradication—since its founding in 1928.

The great energy and aspirations that drove the revolts haven’t disappeared, even if the revolutionary leaders in Egypt have been marginalized for now. There on the margins, they are still working.

Kamel has concluded that the fault lies not with Egypt’s stars, but its citizens. “We have fought four regimes in a row, but most of the people of Egypt are not with us,” he told me this fall. “The problem in Egypt now is not the regimes. It is the people. We have to convince them.”

Some still believe that Sissi’s overreach will drive people together again, just like Mubarak’s abuse of power did in January 2011. “The Mubarak verdict shocked people,” Abdelkareem, the ex-Muslim Brother and Egyptian Current founder currently in exile, told me. “Now the youth are starting to cooperate again.”

Throughout the region, the same force that drove the uprisings has been redirected. Some of it simmers out of sight. Some of it has poured into the call for violent takfiri jihad in Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Egypt and perhaps elsewhere. Some of it has flowed into the quiet, continuing organizing of the political parties, youth movements and civil society groups that challenged status quo power. In Egypt, Sissi’s regime will either have to address these aspirations or fight a constant rear-guard war against dissent. The harder it fights, the more dissenters it will find.

The Tantawi Multiplier

Demonstrators and restaurant patrons listen to Field Marshal Tantawi’s national address at Cafe Riche, near Tahrir Square, on Tuesday evening. Photograph: Thanassis Cambanis

Field Marshal Mohammed Hussein Tantawi’s televised offer of presidential elections sometime before July barely registered among the thousands of young Egyptians jostling to get to the front line of a fight with police that was boiling well into its fourth day. Each casualty seemed to double the number of people cramming into Mohammed Mahmoud Street, eager to charge the phalanx of riot police unleashing a literally non-stop barrage of bullets, rubber pellets, and tear gas.

Call it the Tantawi multiplier effect.

With dozens dead and thousands injured, the calls in the back alleys around Tahrir have escalated. They don’t want Tantawi’s head; they want the end of military rule, period.

“Things have only gotten worse over the last 10 months, as if Tantawi and the military council were punishing people for the revolution,” said Hadi Ismail, a 31-year-old computer programmer. He wore an argyle sweater, a blue canvas blazer, and a face mask against the tear gas. He stood with a trio of friends in a narrow lane swirling with the noxious chemical, taking a break from the battle.

“We gave the military council its power. They have forgotten that,” Hadi explained.

Less eloquently, but in flawless English his friend elaborated: “It’s the same bullshit as before. We need a material change now. No more military rule.”

So long as Tahrir remains full, and the ranks of young people willing to fight police remains undiminished, Hadi and dozens of others I interviewed believe the ruling military junta will inexorably tilt toward compromise and eventually defeat – just like Mubarak.

“All the people are willing to die,” Hadi said matter-of-factly “People are even more aware and determined than on January 28. The second wave of a revolution is always stronger and more violent.”

Out on the square, an older man with missing teeth stopped a pair of youth with tell-tale white smears on their face, traces of a yeast mix that soothes tear gas. “Protect your revolution,” he said, tears in his eyes, and not from any gas. “Save our country from those who are killing it.”

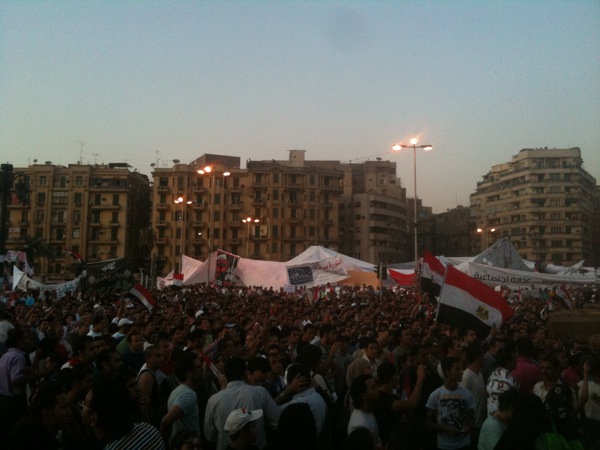

Hundreds of thousands have converged on Tahrir Square, in a manner not seen since the 18 days that felled Mubarak. This time, unlike the last, many of the dead have been paraded on stretchers through the crowd, their corpses reflecting the ghostly street-lamp light like halos.

It’s hard to square the outrage, stoked each hour by the growing body count, with the insouciant language of Egypt’s latest dictator. Tantawi, like Mubarak before him, seems to believe he is dictating terms to an unruly rabble; maybe he even believes his own claim that “invisible hands” are stoking divisions within Egypt.

The boys and girls in the square, the men and women, the unemployed and the well-to-do, express a simple disgust with the police who kill civilians, and the regime which is responsible.

“I’m not asking, I’m giving orders,” said Ahmed Fouad Saleh, himself a retired air force officer now demonstrating in Tahrir Square. “We will have a new government.”

A youth activist who helped establish a new political party earlier this year, Shady ElGhazaly Harb, shook his head in disgust, and a measure of disbelief, at the intransience of the junta that dumped Mubarak as its figurehead but seems to have retained a fair number of his ways.

“They still haven’t learned a thing,” ElGhazaly Harb said. “If they don’t leave power now, these people won’t leave the square. Nothing else will do.”

6 Key Questions on Egypt’s Escalating Violence

Many questions and mysteries as the military, police, and demonstrators wrangle over Egypt’s future; much too much that we don’t know, especially about who controls the police, and how the military makes decisions.

Does public opinion (or the silent majority) matter? The commentariat in Egypt and abroad places a lot of weight on the public opinion that is skeptical of protest, and always was — before January 25, during the initial uprising, and now. These voices, which are loud and important in Egypt, are apt to believe official protestations of “foreign agents,” “hidden hands,” or “secret agendas,” and quick to blame protests for destabilizing the country or hurting its economy, even if there’s no evidence to support that belief. While this view gets trotted out a lot, especially on Egyptian state television, it’s unclear whether it represents a force with any power in Egypt. This year, only a few forces have had any effect at all on politics: the army, the police, the ex-ruling party, the Islamists, and persistent street protesters. Arguably, liberal and other organized political parties have played a bit role. Note that none of these actors represents a huge swathe of society, with the exception of the Islamists. All of them have shaped events this year.

From Tahrir to Wall Street

It was supposed to be a master class in revolutionary activism: two stars of the Tahrir Square uprising visiting Occupy Wall Street to swap tactics and sass. It ended up more like an undergraduate teach-in.

For Asmaa Mahfouz and Ahmed Maher, the visit to Zuccotti Park was an exhilarating – if surreal – break from the punishing workload of fighting the military dictatorship back home in Egypt.

“Where is the tear gas?” Maher asked with a smile, but he seemed genuinely puzzled by the cordial relations between the Wall Streeters and the cops.

Maher and Mahfouz both have been arrested before by Egypt’s notoriously abusive police, and Mahfouz recently was hauled before a military court martial for allegedly insulting her country’s military rulers.

Mahfouz had a question of her own. “Where are the organizers?” she asked. “There must be organizers.” No one knew. She ended up chatting at the welcome table with a young man wearing a straw hat.

“How do you sustain yourselves? How do you keep yourself energized?” he asked. “That’s our main problem.”

“You need a message,” she told him.

She inscribed an Egyptian flag (“From Tahrir Square to Wall Street”) with black marker and presented it to the hundreds who gathered to hear her and Maher.

Mahfouz, 26, spent years protesting when most Egyptians stayed home, and became a phenomenon with her self-produced YouTube editorials. She lambasted rulers with homespun humor, and exhorted people to join her at protests. Eventually they did, in the millions.

Maher, 31, worked with virtually every activist group in Egypt, and founded the April 6 movement, which was instrumental in organizing textile worker strikes in 2008. His grassroots political organization boasts the kind of street muscle and labor ties that Occupy Wall Street still only hopes to build.

People asked about the role of women in the Egyptian uprising, the connections between youth and labor movements, and the importance of social media. Some of the questions were well intended but astonishingly vague: “How do you overthrow a system?” one man asked. Maher politely replied, “It’s easier to overthrow a dictator than an entire system.” He didn’t belabor the point that the Egyptian revolutionaries, so far as they are concerned, have not yet won; they still are fighting their system. Egypt’s military rulers have staged a vicious campaign against Maher’s April 6 movement, accusing them with no evidence of working as American spies and subjecting them to a public inquiry.

The Americans wanted to know how they could help Egypt.

“Get your revolution done. That’s the biggest help you can give us,” Mahfouz said, expressing the hope that America would one day cut off the $1.3 billion yearly payments that sustain Egypt’s military.

She also advised Occupy Wall Street to select its own leaders and craft a simple message “that no one can change.”

On Monday evening at Zuccotti Park, Mahfouz was eager to model the fiery disobedience with which she’s inspired countless Egyptians. “Let’s march!” she said after an hour-long question-and-answer session, grabbing an Egyptian flag and flashing the victory sign with both hands.

A few hundred demonstrators fell in line behind her and Maher, who gamely joined the English chants. The police allowed the march onto Wall Street itself, and at each corner the American leaders consulted an officer about the preferred route. Weary of the somewhat stilted slogans, which lacked the umph and rhythm of Egyptian chants, Mahfouz and Maher taught the crowd the iconic cry of the Arab uprisings: “Al shaab yurid isqat al nizam,” or “The people demand the fall of the regime.” The crowd adopted its own hybrid: “Al shaab yurid isqat Wall Street.”

As they wound back to Zuccotti Park, demonstrators awaited a cue from the police before crossing Broadway. It was too much for Mahfouz. She stopped in the middle of the intersection, stopped traffic, pumped a fist in the air, and demanded the fall of Wall Street. Nervous demonstrators skittered to the sidewalk, leaving Mahfouz with just the cameras and a few dozen stalwarts who seemed willing to accept her invitation to be arrested.

For a few seconds, there was a palpable crackle of tension. But the police, it seemed, didn’t want the hassle. They stepped back, and without a confrontation, the moment subsided. Mahfouz joined her comrades back on the sidewalk.

“I wanted to show them that they need to be tough, even if they get arrested,” she said with her trademark toothy smile. With that she repaired for a private session with Occupy organizers – she finally had found them – and the long trip back to Cairo the following day.

One-Man Tent, Tahrir version

How to keep cool in the middle of a day-long protest in a shadeless square with the sun pushing temperatures to 100 degree Fahrenheit? Here was one man’s resourceful solution on July 8.

Reinvigorating Egypt’s Revolution

CAIRO, Egypt — Friday’s “Day of Determination” (or “Day of Persistence”) continued overnight and into Saturday as a sit-in in Tahrir Square. It was the largest since President Hosni Mubarak stepped down, and it marked a sort of inflection point for the popular uprising that began on January 25.

For the first time since mid-February, the crowd filled the entire square, and drew scores of regular folk who wouldn’t normally define themselves as political activists. The demonstration swelled to revolutionary size, to a large extent, because its organizers consciously eschewed politics. Instead they resorted to a lowest-common denominator appeal to prosecute Hosni Mubarak and his henchmen. Justice for the crimes of the past, and for the crimes that continue, including police brutality, unaccountable government, and military detentions of protesters. Two words echoed above all: justice, and revenge.

That simple call galvanized the protest, although to some was its Achilles heel.

“The blood of the martyrs won’t be wasted,” the crowds chanted. Protesters carried pictures of Hosni Mubarak hanging from a noose (a common motif, also stenciled on walls around Tahrir).

A performer named Waleed Sheikh held a Mubarak marionette wearing the traditional red Egyptian death row suit, a star of David on the front. “I am manipulating him like he used to manipulate us!” Waleed said as he made the Mubarak doll dance, to the wild applause of onlookers.

Many of those in crowd said they hadn’t joined a protest since February, but were galvanized by the ruling junta’s foot-dragging on trials for Mubarak cronies and on police reform.

“I thought the government would be purified after the revolution,” said chemist Mahmoud Fathy, 29. “They are trying to outsmart the revolution, to outwait us and change nothing.”

Day of Persistence on The World

Marco Werman asks me about today’s protests in Tahrir on The World. I’ll post more about this later, but the crowd today was larger and more harmonious than at any point since February, when President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. It certainly marked some kind of turning point in terms of popular impatience with the general who run Egypt, and it might signal something important about the enduring appeal of revolution and the failure, so far, of opposition politics to capture Egypt’s imagination.

Pushing the Boundaries

CAIRO, Egypt — On the fourth day of publication, Ibrahim Eissa bounds into the newsroom of Tahrirnewspaper, his latest anti-establishment venture and quite literally the offspring of Egypt’s January uprising. It’s midday, and he’s ready to plough through the day’s diet of news stories, opinion columns, and satirical cartoons that seem poised to make this tabloid the paper of record for the demographic known here simply as “the youth of the revolution.”

He’s wearing his trademark brown suspenders, and his trapezoidal mustache twitches as he hails the receptionist, the foreign news editor, and the managing editor.

“I’m the oldest person here,” proclaims Eissa, who appears also to be the most energetic. He later explains that youthfulness is a point of pride in Egypt’s gerontocracy, where the octogenarian president appointed septuagenarian deputies to run his police state. Field Marshal Mohammed Tantawi, Egypt’s current leader, is 75.

Tahrir launched at the beginning of July after months of planning. The paper is determined to challenge authoritarianism and corruption, and to cross whatever red lines Egypt’s rulers try to draw around a free press.

“Before, Mubarak was the red line,” Eissa says as he discusses the paper in his narrow corner office, as editors parade through. “Now the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces has replaced Mubarak. They don’t want anyone to criticize them directly.”

Eissa still tends the most boisterous patch of Egypt’s still-tender garden of free expression. At 45, the veteran editor might boast the toughest hide of any Egyptian journalist. During the long tenure of President Hosni Mubarak, Eissa was fired from nearly a dozen jobs and dashed all the regime’s taboos. In 2007, he was sentenced to a year in prison for writing about Mubarak’s failing health, which was treated as a state secret. (The sentence later was overturned on appeal, but the case successfully muzzled the Egyptian press.) For five years, he ran the liveliest paper in Egypt, Al Dostour (“The Constitution”), building it into enough of a threat that in October 2010 Mubarak had a crony buy the paper and fire Eissa the next day.

Read the rest in The Atlantic.

Back in Tahrir for Tear Gas and Detention

I returned to Egypt on Tuesday, escaping the tear gas and riots in Athens for the Cairene edition. I followed the parallel clashes on Twitter, and then headed out to Tahrir. The scene felt different than in February — a somewhat hard to parse mix of earnest protesters, activists, disenfranchised Egyptians, thugs, and soccer hooligans. As I tried to interview the father of a martyr from January, a pair of middle-aged men confronted me, with a mix of bullying, menace and manhandling that I’ve come to associate with regime figures or their henchmen. “How do we know you’re not a Jew?” one of them demanded. He had white hair and wore a light blue suit. With prompting from the crowd that assembled he demanded my Egyptian press card, which he grabbed, crumpled up, and stuffed in his pocket. After some shoving and shouting, he resolved to present me to the police — obviously, he said, I was a spy and not a journalist. (You can see him in the middle of the group pictured here; I snapped this with my iPhone while the citizens brigade contemplated what to do with me.)

The police officers at Marouf Street were unimpressed. They sent the man and his small mob on their way, and after a short time, the duty officer turned to me. “Imshee,” he said, “leave”* — one of the chants the crowds in Tahrir used to direct at Hosni Mubarak when he still was president.

You can read more detail about the day in my dispatch at The Atlantic.

CAIRO, Egypt — The city is combustible. On Tuesday night, seemingly out of nowhere, fighting engulfed Cairo at a pitch not seen since the Days of Rage in January and February that forced President Hosni Mubarak to resign.

A group of families had gathered in another neighborhood to celebrate the martyrs killed during the revolution; no one knows who organized the event and who attended. No one knows exactly what happened next either — just that police tangled with the families, who then decided to march on the Ministry of the Interior in downtown Cairo. After nightfall, the fighting took on a momentum of its own. Hundreds of demonstrators massed at the interior ministry and later in Tahrir Square. Riot police shot tear gas and, according to protesters, rubber bullets. Demonstrators threw rocks and Molotov cocktails. The fighting surged on throughout the night, unabated.

By noon on Wednesday, several thousands of demonstrators were still battling the riot police. Reinforcements had arrived, including 20 ambulances. The fighting raged on Mohammed Mahmoud, the spur street off the southern end of Tahrir Square leading to the interior ministry. Men on ambulances ferried the hundreds of wounded back to the ambulances. The sting of tear gas stretched half a mile from the clashes, enveloping the entire square. Helpful men offered vinegar and Kleenex to alleviate the pain of inhaling the gas.

I was eager to talk to some of the martyrs’ families, find out how the whole melee began, and see how they felt it would affect their cause. Men and women huddled in knots, ignoring the tear gas, arguing about whether these clashes would undermine the revolution by alienating a wider Egyptian public that is tiring of protests. None of them were relatives of martyrs. Many of them were wary.

“I’ve been in Tahrir since January 25, and a lot of the faces I see out here today are not the usual faces,” said a 27-year-old accountant named Mahmoud. “A lot of them look like thugs.”

*In the original post, I had incorrectly written “emsha” for “imshee.”