Can Militant Cleric Moqtada al-Sadr Reform Iraq?

[Read the full report at The Century Foundation.]

In the fifteen years since the American invasion toppled Saddam Hussein from power, Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr has distinguished himself from other emerging Iraqi leaders with his endurance, iconoclasm, and unpredictability. He has cut a bedeviling and at times magnetic figure in his country, and he is one of the few sectarian leaders whose popularity has crossed sectarian lines.

Through war, flips of allegiances, involvement in corruption, and military victory and defeat, Sadr has managed to preserve his maverick image as a stubbornly independent man deeply committed to his principles, even as those principles shift over time. Now, with the May 12 Iraqi elections approaching, he is trying to parlay his reputation as a nationalist free-thinker into a movement that can transform Iraq’s political system.

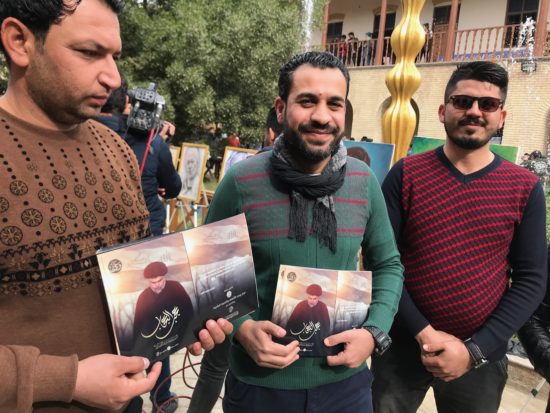

In fact, Sadr has fashioned himself into an unlikely tribune of reform in Iraq. A persistent thorn in the side of foreign powers and Iraqi politicians alike, the graying forty-four-year-old is now trying to radically reshape his country’s politics. He has freshly renounced religious sectarianism, building an alliancewith Communists and secular reform activists.1 He has attacked Iraq’s corrupt spoils system, with slogans such as “corruption is terrorism” that resonate with millions of disenchanted Iraqis. His unorthodox electoral campaign joins Shia partisans, Communist ideologues and some of Baghdad’s secular elite. Sadr’s popularity, hard power, and unifying message make him a direct threat to Iraq’s political class.

Even though his movement is unlikely to win a majority, Sadr’s unique campaign and nationalist-religious-secular alliance has upended nostrums about Iraqi and Middle Eastern politics. He hopes to establish new guiding principles: Sectarian movements can change their politics and become secular and nationalist. Armed militants can take part in electoral politics and government. Sectarian constituencies can embrace nonsectarian principles and support power-sharing and coexistence.

The evolution of Sadr and his movement has unfolded along pragmatic lines, with many flaws and inconsistencies. Nonetheless, Sadr’s political makeover amounts to a groundbreaking and encouraging transformation. It compels other established movements in Iraq to address the core challenges of security and governance, while building trans-sectarian or nationalist coalitions. He sets an example for other leaders and political organizations interested in exiting the confining boxes of sectarianism and patronage and mobilizing broader, more fluid and inclusive idea- or policy-based movements.

The success of Sadr’s approach and platform is more important than that of his candidates. If his coalition is repudiated by voters, or abandons its plans to challenge poor governance, then we can expect more of the dispiriting business-as-usual from Baghdad. But if Sadr follows through after the election and promotes the formation of a platform-based government with a legislative opposition, then we can expect Iraqi politics to enter a new phase, moving away from narrow sectarianism and patronage-only politics. A transition to a government with some technocrat ministers, a real opposition, and some pretense of nonsectarianism is necessary if Iraq is to begin addressing policy problems that affect the stability of the entire Middle East. The most pressing concerns include securing and developing the areas liberated from the Islamic State and reincorporating Sunni Arabs and Kurds into Baghdad’s fold.

This report traces Sadr’s evolution, and both the perils and promises of the road ahead. It is based on more than forty interviews conducted in Iraq in February and March 2018, with support from a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Charismatic Provocateur

Iraqis have long bemoaned a lack of leadership and vision within the ruling class. The melee of corruption and militia-formation that has plagued Iraqi public life since 2003 has featured a parade of politicians and warlords, many of whom have evolved into effective operators. Yet only two indisputably strong, charismatic leaders have distinguished themselves from the fragmentary society of party bosses, warlords, tribal leaders, and the grifters and opportunists who have made deals with the wardens of cash. Those two are both Shia clerics, and no love is lost between them.

The first, and most influential, is Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the single most authoritative leader in Iraq. A cleric of impressive intellect and conservative (rather than radical) nationalist views, Sistani is credited as a moderating force who at times kept Iraq from civil war and at others helped mitigate the scope and damage of sectarian conflict.

The other enduringly powerful figure is the far more junior Sadr, who in the wake of the U.S. invasion emerged as a strong counterpoint to Sistani’s style of leadership and modest ambitions. Sadr lacks the educational pedigree of the ayatollahs who are considered “marjaiya,” or sources of emulation, and whose teachings are followed by millions worldwide. Still, Sadr inherited the millions of passionate followers of his father and uncle, both revered ayatollahs; and he also continued the family feud against Sistani, whom the Sadrs regarded as too timid.

Sadr was not yet thirty years old when the United States invaded Iraq. His family organization already included a nationwide network of staff and offices, and Sadr quickly leveraged these to assemble a committed militia, the Mahdi Army. He emerged as a powerful and unpredictable force—violently opposed to the American occupation as well as to homegrown Sunni extremists.

Although he is a Shia cleric, Sadr made it clear with his rhetoric and style that he was first and foremost an Iraqi nationalist, not beholden to foreign powers, whether Iran, the United States, or another country. From 2004–08, the Mahdi Army forged a fearsome record of violence, fighting at different times against U.S. forces, Sunni sectarians, and fellow Shia movements. His fighters rallied, at least initially, under the banner of resisting the American occupation. In the first years after Saddam’s fall, the Mahdi Army and the Sadrist political organization made symbolic overtures to non-Shia resistance groups and expressed a willingness to ally with Iraqis of any sect or ethnicity (a commitment evident more in rhetoric than in practice). As a result, and especially in the early years following the invasion, Sadr was one of the few militia commanders who enjoyed at least some grudging respect across sectarian lines. The ensuing decade dulled his sheen somewhat, as his soldiers were implicated in some of the same abuses and sectarian violence as other factions, and his political partisans, the Sadr Movement, proved every bit as susceptible as other parties to the temptations of corruption. In 2008, Sadr officially disbanded his Mahdi Army militia, although much of its structure and membership survived in other guises within the Sadr organization. In 2014, in response to Sistani’s call for fighters to resist the Islamic State, Sadr launched Saraya al-Salam, (“Peace Companies” or “Peace Brigades”), a successor militia to the Mahdi Army which included most of its veteran officers who hadn’t moved on to other, more militant organizations.

Sadr’s trajectory has not been a simple one-way ascent from militia strongman to political player. His story abounds with course-changes and seeming contradictions. For example, he has witheringly attacked the Iraqi political system, even as he has deeply embedded his politicians within it. And though in 2018 he has mounted a new campaign against corruption, throughout the post-invasion years, Sadrists won a hard-earned reputation for epic corruption in their government fiefs, including the lucrative and critical health ministry which they controlled from 2006–07.

Unlikely Partners for Reform

In 2015, the rise of the Islamic State shattered the business-as-usual trajectory of Iraqi politics. Sectarianism had flourished, along with the corrupt spoils system. But foreign influence on Iraqi politics, along with security services crippled by corruption and no-show ghost soldiers, was no match for the Islamic State. Many Iraqis already had reached a breaking point because of raging unemployment and the government’s failure to provide basic services like electricity. Basic services had never been fully restored since the American invasion of 2003, despite years of banner oil profits, mostly lost to corruption. Protest camps sprung up around the country. In Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, followers of Sadr got to know followers of the secular reform parties, including the Communists. Over time, trust grew. Leaders of the secular parties were invited to meet with Sadr.

By the time the Islamic State shattered Iraq’s sense of security, Sadr was already changing course. With the protest movement, he adopted a newly moderate and inclusive rhetoric. Sadr threw his weight behind the protesters. He encouraged his political movement and followers to make common cause with secular reformers and independent technocrats. His followers ceased their very public attacks on homosexuals. “He has undergone a change, an evolution,” said Raid Jahid Fahmi, the secretary general of the Iraqi Communist Party, who has led the secular embrace of the cleric Sadr. “You will find a change in his vocabulary and thinking.”2

“Sadr is ready to cooperate with anyone with Iraqi interests,” said Fahmi. “This was a very important cultural shift.”3

After joining forces with protesters from other factions in 2015, Sadr and his top lieutenants repeatedly met with potential partners. Over time, leaders in the Iraqi Communist Party and the Iraqi Republican Party, led by a secular Sunni pro-American businessman named Saad Janabi, grew convinced they could trust Sadr—and that they would be given an equal role in designing the alliance, even though their parties were much smaller than Sadr’s following.4

“Moqtada al-Sadr is the only person who can summon one million people with a single call,” Janabi said. Secular Iraqis and even some sectarian Sunnis have come to believe Sadr’s nationalist rhetoric, he added.5

In coalition with his new partners, Sadr said he would support an entirely new group of technocratic candidates under a new name. He disbanded his existing “Ahrar” parliamentary bloc, with thirty-four members. He ordered them all not to run for reelection, clearing the way for a new slate of technocrats—the vague term of choice for Sadr and his movement to describe the putative category of professional, independent experts who they believe could improve the Iraqi government’s performance, unfettered by sectarian or political allegiances. Sadr’s new party is called “Istiqama,” which means “integrity,” and the overall coalition with the Communists and other smaller members is called “Sa’iroun,” which means “On the move,” or “Marching,” with the intention of evoking a march toward reform. The alliance’s goals are clear: a civil, secular state, run by technocratic experts who can fight corruption and improve governance.

Sadr’s New Platform in Context

Sadr’s record makes his positioning today all the more interesting. In the pivotal 2018 parliamentary elections, he has declared himself the leading opposition reform candidate. Some of his new claims strain credulity because of his checkered record, but his sheer power and loyal following mean he always has potential as a kingmaker. Electoral math makes unlikely his ambitions of winning the prime minister’s job for his political movement, but he is establishing an entirely new style of politics and rhetoric, which holds critical promise for Iraq and possibly for the entire region.6 First, he has fashioned a potentially inclusive national narrative from the grisly history of sectarian violence that has buffeted Iraq since 2003. Second, he has deftly eclipsed paralyzing political binaries, by forming an alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party and a small array of independent, secular reformists. Third, he has spurred an open discussion of the central problem of Iraqi politics: the “muhasasa” system, most accurately rendered as the “allotment” or “spoils” system.

“This alliance is something new,” said Fahmi, the Communist leader, who has led the secular embrace of Sadr.7 “The political process must shift to a citizenship state from a constituency state. The sectarian quota system is incapable of giving solutions to the problems of the country.”

Since the fall of Saddam’s dictatorships, elections have done nothing to dent the sectarian-based patronage structure in which there is no opposition to the government, but only a shifting free-for-all to feed at the public trough. Elections merely determine what share of power each party gets—the more votes a party secures, the more profitable the ministries to which it lays claim. No successful party has ever refused to take part in the government, joining in the broken-piñata frenzy of corruption that has characterized Iraqi governance at least since Saddam’s era.

The 2018 elections come at a moment when much has changed in Iraqi politics, and Sadr has carefully shaped his movement to make the most of it. The upcoming vote arrives on the heels of a successful military campaign against the Islamic State (in which Sadr’s fighters played an important role), and the coming of age of Iraq’s Shia sectarian militias and Islamist parties. The Shia Islamist militant parties have dominated Iraq since 2003. They have defeated their main external rivals and corralled Kurdish separatism. They have fought each other, sometimes in bitter political contests and at times in outright war, as in 2008 when Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki drove Sadr’s Mahdi Army out of Basra. Today, being a Shia Islamist militia no longer serves as a politically distinguishing identity. All the major electoral coalitions are led by Shia politicians, and most include some Sunni and Kurdish partners and candidates. Fissures within the Shia political space have strengthened other layers of political identity. Politicians now distinguish themselves by their approach to securing Iraq in the future from a resurgence of the Islamic State; balancing the influence of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United States; and solving the nagging problems of poverty, development and corruption. While other Shia political parties are experimenting with nationalist identity in the wake of the campaign against the Islamic State, Sadr has been identifying as a nationalist for years. He stands out further still by his vigorous support for the idea of a civil, even secular, state.

Security officials still worry about continuing threats from the Islamic State, but according to some Iraqi analysts voters have already moved on. Polling, they say, shows that Iraqis are more concerned about livelihoods than anything else. “Security is no longer a priority,” said Sajad Jiyad, head of the Bayan Center, a think tank in Baghdad.8 “They’re asking for jobs, not for security.”

Yet even as Iraqi politicians pivot to face these new voter priorities, the electorate is meeting them with increasing suspicion and cynicism. Sadr has presented himself as something of a political outsider—and certainly not one of the Baghdad elite. His reinvention as a coalition builder enhances his appeal, suggesting he means it when he says he is ready to do business in a new way.

“The state is failing,” said Dhiaa al-Asadi, leader of the current Sadrist bloc in parliament and a political operative very close to Sadr.9 “The existing political elite are part of the problem. They can’t be part of the solution.”

Sadr wants to see the militias formed to fight the Islamic State fully reintegrated into Iraqi government control. He wants sectarian quotas abolished for public sector jobs and government positions. He wants a carefully balanced foreign policy that keeps Iraq equidistant from Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United States. He has also been one of the only important Iraqi Shia leaders to oppose the involvement of Iraqi Shia militias in the Syrian civil war.10 He wants to come to terms with separatist Kurds. Above all, he wants to jumpstart the moribund economy to provide jobs and salaries to Iraqis—the poorest of whom are disproportionately part of Sadr’s following.

In this context, Sadr’s frontal challenge to the central narratives of Iraqi governance since 2003 has the potential to force the ruling parties to shift their rhetoric and approach. Indeed, the process can already be seen in action.

Bridging Old Rifts

Take, for example, Sadr’s changing relationship with Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who, despite reservations about Sadr that have at times erupted into violent confrontation, has continued to court and collaborate with the cleric. Abadi has gone so far as to adopt some of Sadr’s rhetoric. One billboard at the entrance to Baghdad shows Abadi’s face and reads, “corruption and terrorism have one face,” echoing the Sadrist protest slogan, “corruption is terrorism.”

Abadi’s wary embrace of Sadr is especially significant given that the many of the latter’s supporters view Abadi as a villain. One recent demonstration, in February, marked the one-year anniversary of the death of fourteen demonstrators—killed at the hands of Abadi’s security forces while marching toward the Green Zone. Marchers carried flag-draped coffins commemorating the “martyrs for reform” in the same manner that they would honor martyrs who died fighting the Islamic State.

Abadi and his allies have opted to accept Sadr as a potential partner, although Sadr’s critical rhetoric has made them wary. “I think we should distinguish between the election campaign and the reality,” said Sadiq al-Rikabi, a member of parliament and a close ally of the prime minister.11 “It is very easy to stand against corruption,” he added, but much harder to articulate tangible policy proposals.

Perhaps even more significant than Sadr’s partial rapprochement with Abadi is that with Sistani. Despite Sadr’s persistent popularity, Sistani’s influence remains more important—but also more diffuse. Sistani’s clout with Iraqi Shia is not absolute nor instrumental; he doesn’t directly control any political parties or militias, and despite his extensive efforts, he has been unable to persuade Shia politicians to avoid corruption, violence and sectarianism. Still, his edicts hold force. It was a fatwa from Sistani in 2014 that created the popular mobilization units (“al-hashd al-sha’abi,” or PMUs). Almost all Shia in Iraq heed Sistani’s edicts, and he has been credited on multiple occasions with limiting the deleterious impact of Iraq’s worst crises. Sistani has telegraphed his disappointment with the record of the Shia Islamist parties that have dominated Iraq’s government since the 2005 elections. The Shia parties almost uniformly try to claim the approval of Sistani and the other senior Shia clerics, even when Sistani has made clear that he supports none of them. Sistani warned leaders of the Shia militias not to parlay their battlefield success into political campaigns, but most of them ignored the order, to Sistani’s chagrin.

In an interview, a representative of Sistani criticized militia leaders for seeking “political advantage” from the “blood sacrifice” that Iraqis of all sects made in the resistance against the Islamic State.12 As the parliamentary campaign has heated up, Sistani has made his displeasure even more clear. One cleric close to Sistani went on Furat Television to warn voters not to make their choice based on sect.13 “The corrupt people we have voted for have robbed the nation. We ought to not vote for them again, even if they are members of our clan or sect,” said the cleric, Rashid al-Husseini.14 “I would rather trust a faithful Christian than a corrupt Shia.”

Historically, Sadr has been at odds with Sistani and the other senior clerics in the marjaiya. In the current campaign, however, he has closely shadowed Sistani’s pronouncements about corruption and the need to elect new leaders. In recent statements, Sadr has addressed skeptical voters who have lost faith in the political process because of the corruption and failures of previous Iraqi governments, including those with the participation of Sadrists. “We will not be deceived by the lies again,” Sadr wrote in an April 14, 2018 statement.15 His own movement’s previous failures, he said, “give the motivation and determination to succeed in this election.”

On April 4, 2018, Sadr released a series of arguments against boycotting the elections. “Some ask, and say: the corrupt and the old faces will stay in power whether we vote or not,” Sadr wrote. He offered thirteen rebuttals, evoking religious loyalty, patriotism, optimism, and the responsibility of citizenship.16

In today’s Iraq, Sadr boasts a unique status.17 He can count on nearly absolute devotion from his rank-and-file followers, his organization, his political party and his militia. Even Sadr’s opponents recognize his political heft. In this, he is different from other Iraqi religious leaders only in degree: Mowaffak al-Rubaie, a former national security adviser who is close to several senior Iraqi politicians, said that millions of Iraqis venerate clerics and will do whatever those clerics instruct.18 During a visit by Sadr to the Kadhamiya shrine in Baghdad, Rubaie recalled, Sadr’s followers crowded the cleric’s jeep to touch the dirt on its wheels, which they smeared on their heads as a blessing. “If he orders these people to set themselves on fire, they will do it,” he said.

Sadr’s positions have appealed to Iraqis who are weary of conflict but seek to maintain dignity and integrity in their foreign relations. For example, Sadr has softened his rhetoric about secularists, and has been willing to mend fences with Saudi Arabia and criticize Iran. But at the same time, he has maintained a hard line against the United States, whose influence in Iraq he considers wholly malign.

The fact that those positions are accommodating while remaining tough and without being overly compromising—much like his evolving relationships with Abadi and Sistani—make his calls for unity that more meaningful.

“Healing is gradual,” he said in the April 14 statement. Iraq has never before experimented with professional technocratic politicians, “without any partisan or religious or ideological or ethnical indications, to choose the most effective and the best [leaders] for the love of Iraq, and the love of Iraq is of faith.”

Managing Expectations

If this account of Sadr’s well-timed transformation into a champion of nonsectarian political reform sounds a little too gung ho, there are plenty of structural and historical reasons to readjust expectations to a more realistic level.

The results of the May 12 election are likely to set in motion a long negotiation process; many seasoned Iraqi politicians and analysts believe the outcome will be another unity government like all those that have ruled Iraq since the U.S. occupation, with goodies and power divided among sectarian parties. Sadr has pulled many about-faces before; he may tire of the alliance with secular parties, or he might decide he can better serve his constituents by joining yet another weak coalition government. “Moqtada al-Sadr has been on television and in politics for fifteen years and he has accomplished none of his goals,” said one political insider close to the government. “He has been revealed to be someone who cannot be trusted.”19

Fighting Sectarianism

Specific aspects of Sadr’s past raise questions about his sincerity. For example, despite his maverick image, he has played his part in the problem of sectarianism. The Mahdi Army orchestrated some of the worst ethnic cleansing and sectarian killings of 2006, although Sadr subsequently pulled his loyalists back. Many of his extremist supporters defected to other organizations or founded their own, like Qais al-Khazali, who is now the leader of Asaib al-Haq, a Shia militia close to Iran.

Some secular leaders never overcame their mistrust of Sadr, with his religious background and history of secrecy and political about-faces. One of the secular reform leaders who rejected the coalition is Shirouk al-Abayachi, leader of the National Civil Movement and a member of parliament.20 Sadr’s organization is “foggy” and evasive, she said. “One year ago they would call us infidels,” she said. “We don’t know what they want from us.” If the Sadrist alliance does well in elections, she said, history suggests that Sadr and his lieutenants will make the important decisions, rather than deferring to the independent secularists from tiny parties. “We don’t just want seats in parliament,” Abayachi said. “We want to build a clean alternative.”

Despite his conciliatory reform rhetoric, Sadr has been willing to turn to outright confrontation with the state. Despite his status as a junior partner in the Iraqi government, Sadr personally broke through the security cordonsurrounding Baghdad’s Green Zone in March 2016.21 His followers set up a protest camp in the heart of the government, even briefly occupying parliament and the prime minister’s office.

Pervasive Corruption

When it comes to fighting corruption, there are similar reasons to moderate enthusiasm for Sadr.

Existing anti-corruption efforts suggest it will be difficult to make meaningful inroads against the spoils system. “The system needs to be reformed but there is no incentive to reform,” said Ali al-Mawlawi, director of research at the Baghdad think tank the Bayan Center.22 “The government has hard evidence, but the corrupt judiciary won’t prosecute.”

Even Sadr’s own politicians have struggled to have an impact, and critics of Sadr’s reform program point out that it is short on specifics. Jumaa Diwan al-Badali is a Sadrist member of parliament who represents the poor Baghdad district of Sadr City (which takes its name from Moqtada al-Sadr’s father, Mohammad al-Sadr); Badali is also the rapporteur of parliament’s integrity committee, in charge of investigating corruption. His experience shows the limits of any serious effort at reform. His committee has publicized some problematic contracts, often resorting to media leaks to force the government to pay attention. Parliamentarians have uncovered kickbacks and fishy contracts in the department of defense, including one case, Badali said, where the department attempted to buy subpar and nonexistent equipment for the fight against the Islamic State.23

The biggest contract they stopped was a $2.5 billion weapons deal with China, which was part of the 2017 budget. Badali believes the U.S. encourages corruption in Iraq as a way of keeping the country and its security forces weak. “I don’t accept the prime minister’s depiction of Iraq as a pool of corruption,” he said. “We are a country with some corruption. We are not the most corrupt country in the world.”

Aside from the general difficulty of rooting out corruption, Sadr and his allies are hardly innocent of graft themselves. Sadr’s militia, the Saraya Salam (“Peace Brigades”), a PMU created in 2014 from the remnants of the Mahdi Army, has benefited from government funding. Corruption clearly played a role in eroding the combat readiness of Iraq’s security forces prior to the rise of the Islamic State, but the rise of new security institutions, including the PMUs, has only fueled the type of corrupt militia patronage that has hobbled the central government.

Over the years since 2003, Sadrist ministers and members of parliament joined the corruption frenzy as well, taking kickbacks and doling out patronage jobs through ministries under their control. Sadr’s principal secular ally, the Iraqi Communist Party, also enjoyed influence through the spoils system, winning positions in the cabinet despite very winning very few votes. Fahmi, the current Communist leader, served as minister of science and technology from 2006 to 2010. Fahmi preserved his reputation for probity through his time in government, although—critics of the Sadrist reform project are quick to point out—he wasn’t able to roll back corruption by other parties in government.

“Who can fight corruption?” said Ahmed al-Krayem, a tribal leader and provincial politician who alleges that Sadr’s followers and fighters participate in the same kickbacks and extortion schemes as every other Iraqi political party and militia group.24 “The Sadrists won’t fight corruption.” Even the prime minister, Krayem pointed out, has been dogged by allegations of corruption from his earlier stints in government before taking over as premier.

Interestingly, Sadr doesn’t refute charges that his own movement is implicated in the failures of past attempts to root out corruption, but rather insists that change depends on continuing engagement and changing tactics. “We didn’t hope to be corrupted,” he wrote in answer to one supplicant who asked how Sadr justifies his political campaign given that his movement has participated in every single one of the corrupt governments since 2003. “We are rising up against the political process from the inside, rather than from the outside.”

Profound Political Problems

Some of the differences within the Sa’iroun coalition seem unbridgeable. Sadr’s Shia followers fought the United States and died in droves. Janabi’s secular followers include many elite Sunnis who are openly fond of the Americans. The Communists, meanwhile, have a long history of tensions with the clergy. Still, supporters of the alliance say these differences won’t lead to political fissures. “Sadr can control his people if there are problems. We will control our followers,” Janabi said. “We agree about fighting sectarianism.”

Another sticking point for Sadr’s agenda may be that the idea of apolitical “technocrats” who just get the job done may be something of a fantasy—at least for Iraq.

Even Sadr’s supporters point out that technocrats can only have impact if they are effective politicians. “I don’t believe in technocrats,” said Hakim al-Zamili, an influential Sadr lieutenant who runs the parliament’s security committee.25“Only a strong politician with a base in a political party can succeed. The country is full of militias, people with weapons in the streets. An independent technocrat without a political party can’t do anything.”

Independents have served as ministers in Iraq since 2003, and none has managed to change the system. The types of figures who can change the system, Zamili said, are tough political veterans with the backing of formidable parties. “Maybe a political technocrat like me can do something,” he said. “No one can threaten me, no militia. I can speak, I can interrupt someone, no one can stop me.”

Iraq’s system is broken; it might benefit from repairs, but Iraqi voters should not expect a wholesale revolution. “Let’s be honest—we can’t accomplish everything we are planning,” Zamili acknowledged.

Murder in Samarra

Power politics in Iraq can play out at a visceral level, and one recent incident has underlined both the frailty of Sadr’s new vision, and its promise.

Sadr has repeatedly taken the position that there should be only one central authority in Iraq—the state—and that all militias must be integrated into government control. At the same time, he commands thousands of militia fighters in the Saraya Salam, most of them stationed in the flashpoint shrine city of Samarra, north of Baghdad. Samarra is a mostly Sunni city that is home to one of the most holy spots for Shia Muslims, the site where it is believed that the twelfth imam went into occultation in the ninth century. Sunni extremists blew up the Shia shrine in Samarra in February 2006, setting off one of the deadliest periods of sectarian fighting in Iraq. Islamic State fighters held sway in Samarra until Shia militias drove them out in 2014.

Since 2015, Sadr’s militia has held sole control of the city. According to Sadrists and Saraya Salam commanders and fighters, their tenure in the city has been a model of success. They have formed partnerships with local business owners and tribal leaders, most of them Sunni, and have restored security and the business that comes with pilgrimage traffic. Critics accuse the Sadrists of ruling the city with an iron fist, detaining political critics, and extorting money from local traders and business owners. The accusations were repeated in multiple interviews with the author, and aren’t out of the ordinary in Iraq; in fact, the accusations levied against the Sadrist militia are much milder than those heard in zones ruled by other Shia militias, where displaced Sunnis live in fear of disappearance and, in some places, of summary execution.

The fact remains that the Sadrists are running a fiefdom, a state-within-a-state in Samarra; while such behavior is the norm in today’s fragmented Iraq, it contradicts the Sadrist platform of reforming the state under a unified nationalist banner. In March, the dangerous equilibrium resulting from so many overlapping security forces collapsed with a shootout between allies in Samarra. On Tuesday, March 13, the prime minister’s personal security detail was driving north in a convoy, preparing for Abadi’s planned visit later in the week to Mosul. The road took them through Samarra. At the town’s main checkpoint, according to two members of a committee that investigated the incident, the convoy refused to stop at the Saraya Salam checkpoint, as they are required to by law.26 Commandos from Battalion 57 of the Iraqi Army, the prime minister’s special unit, went so far as to confiscate weapons from some of the Saraya Salam fighters at the checkpoint. “It was humiliating,” said one of the members of the investigative committee that visited Samarra days later.27The angry fighters radioed ahead to the next checkpoint, a kilometer away, where Saraya Salam militiamen blocked the road with Humvees and confronted the convoy. Dozens of gleaming black sports utility vehicles swarmed the checkpoint. The army unit then fired toward the checkpoint. The Sadrists returned fire, killing Brigadier Sherif Ismail, the battalion commander and a trusted supporter of the prime minister.

Both Sadr and Prime Minister Abadi avoided public recriminations, and ultimately the killing was settled through a tribal agreement. The military unit, according to the investigative committee, was at fault for ignoring proper checkpoint procedures. “We need to develop a culture of respect,” said Zamili, the Sadr lieutenant, who was one of four members of the investigative committee. Another member of the investigative committee, who is not from either the prime minister’s or from Sadr’s bloc, blamed a lack of professionalism. “They were arrogant. They wanted to show off, they didn’t want to follow the rules,” the member said. “It was 100 percent an accident.” Political, military and economic power are inextricably intertwined, and state authority is severely compromised. This particular killing strained but did not break the alliance between Abadi and Sadr, but it revealed yet another potential point of rupture. Tellingly, it was resolved not by the judicial system or by a formal political process, but by a combination of ad hoc investigation and informal tribal justice.

Turning Point Election

The 2018 elections will set the course for Iraq’s government for at least another four years. If the current spoils system continues, with every major party joining into yet another ineffective unity government, Iraq can expect to repeat similar crises. It will be nearly impossible to maintain the effective national security approach that defeated the Islamic State—an approach that required unified command, mass mobilization, and help from all of Iraq’s competing allies, including Iran and the United States. Economic development will require warm relations with Iran, the United States and Saudi Arabia, and, at the very least, a curtailing of rampant corruption. None of these improvements will come to pass without a powerful prime minister, a meaningful opposition, and competent ministers. Sadr’s trailblazing coalition marks a crucial possibility for Iraq: the mainstreaming of civic-secular nationalism, and the passing of national politics from sectarianism into a new phase. More emphatically than any other leader, Sadr has abandoned religious and sectarian discourse, showing that a Shia cleric with a sectarian base can embrace civic, secular politics. There is, of course, ample precedent for such politics in the last century of Arab political history, but sadly, very little among contemporary Iraqi political leaders.

An informal quota system reserves the most important job, prime minister, for a Shia, and the presidency and speaker of parliament for a Kurd and Sunni Arab respectively. If this new tradition survives another electoral cycle, it will fast become the kind of pernicious unwritten tradition that cannot be changed—like Lebanon’s sectarian quotas, which have become unassailable even though they are not in the constitution.

In his alliance with Communists and secularists, Sadr has mainstreamed civic politics. If he sticks with his current course, he can also set an example for other leaders who are willing to move past their origins as sectarians, clerics, or militia leaders. Despite his pointed anti-Americanism and history of armed resistance, the United States should welcome Sadr’s new role. So should Iran, which hoped to make Sadr into one of its proteges before the cleric broke with Tehran as well. Sadr’s broadsides against the United States (his lieutenants regularly brand the Baghdad embassy as a “devil” spreading sedition and strife in Iraq) shouldn’t obscure the common interests he shares with the United States and its Iraqi partners: building a strong, effective government and encouraging a nonsectarian, inclusive national identity that can help end the cycle of sectarian violence.

Sadr’s new rhetoric, and his secular political alliance, mark one of the most promising developments in contemporary Iraqi politics. There are plenty of reasons to question his sincerity, or the durability of the partnerships he has forged since 2015, but those partnerships hold the potential to change the tenor of the entire political playing field. Sadr’s reinvention of himself from militant cleric to nationalist anti-sectarian statesman comes at a time when other sectarian movements have begun to realize that they will need support from multiple constituencies in order to survive politically. In the likely event that the alliance doesn’t win enough seats to form a government, it can contribute still more profoundly to Iraq’s political development by opting to stay out of power and serve as a parliamentary opposition. Iraq stands at a turning point, where its largely sectarian political movements are experimenting with nonsectarian politics, and where its ruling class is confronting the dead-end to which the spoils system has brought the country. Sadr’s gambit stands a chance, albeit a slim one, of catalyzing the political transformation that Iraq so sorely needs.

To be sure, Iraq will still play host to endemic corruption and patronage, but a sharp change in politics can expand the government’s agenda to include long-term governance along with the usual business of padding state contracts and doling out ghost jobs. Without the sort of transformative nationalist, professional, and anti-corruption politics advocated by Sadr, Iraq is sure to face an ongoing cycle of crises that will destabilize not only Iraq, but also its neighbors and U.S. interests in the Middle East.

TCF foreign policy podcasts online

After some experimentation over the summer, TCF has finally — officially — launched its foreign policy podcast channel. You can subscribe on iTunes or Podbean.

The first four episodes are up, including a conversation with Lina Attalah about press freedom in Egypt, some thought about Hezbollah and Iran, ISIS, and the next stage in Syria.

Podbean Channel: https://thecenturyfoundation.podbean.com/

iTunes Channel: https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/id1295785057

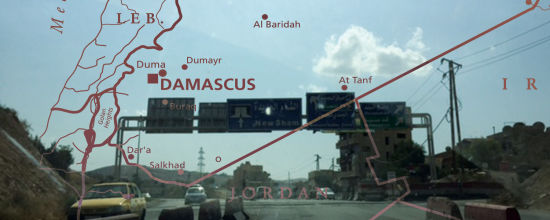

Interview with TCF’s Sam Heller about Damascus trip

Century Foundation fellow Sam Heller returned to Beirut from Syria over the weekend, where he attended a government-backed conference—the first of its kind in years, with Western journalists, analysts and political researchers invited to hear the government’s point of view. He spent a week in Damascus. Century Foundation fellow Thanassis Cambanis talks with Sam about his first impressions.

Thanassis: Welcome back from Syria, Sam. We’re glad to have you back in Beirut. When was the last time you were in Syria prior to this trip?

Sam: I lived in Syria between 2009 and 2010, but I haven’t been back since. I actually left Syria to do a two-year master’s degree in Arabic that would have taken me back to Damascus for its second year—but that was 2011, so that obviously didn’t happen.

Since I turned back full-time to researching Syria in 2013, I’ve devoted most of my time and energy to looking at the Syrian opposition and Syria’s opposition-held areas. What I’ve understood about conditions inside regime-held western Syria, including Damascus, has been filtered through the media or second-hand fragments, from people who travel in and out.

But for all I’ve written about Idlib, I’ve never actually been there. It’s Damascus—and, to a lesser extent, al-Hasakeh in Syria’s east—that reflects my actual, lived experience in Syria. And so it’s good to be back and see the situation in the part of the country I knew best, if only to further ground myself in something real.

Thanassis: What was your first impression on this trip?

Sam: I don’t think this trip necessarily upturned my understanding of conditions inside. But it was useful to see things firsthand and to be able to put some meat on my existing impressions of the functioning of the regime and life in government-held areas.

And this might be shallow, but for me—as an outsider, and as someone who missed the worst years of the war in Damascus in 2013 and 2014—I was struck by how much was the same. The city and the society have obviously been militarized; Damascus is filled with checkpoints and uniformed men. And it seems like everyone, if you ask, has a story of economic hardship, displacement, or the death of friends and family. And yet, even while everything is sort of worse, much of what I knew about Damascus is still there.

One Less Danger but No New Hope as Lebanon Finally Elects a President

Aoun sits at Baabda on election day. Source: OTV screen grab

[Commentary for The Century Foundation.]

Michel Aoun’s ascendance to the presidency of Lebanon on Monday three decades after he first sought the office represents not a sea-change in regional power dynamics but an incremental step in the hard slog of making politics. Nearly two and a half years after the previous president left Baabda Palace and after forty-five failed parliamentary sessions to select a new leader, a thorny dispute with many players was peacefully negotiated. Remarkably, the maneuvers unfolded peacefully despite the pressure caused by a state collapse next door in Syria and with considerable threat of violence hanging over Lebanon itself.

The outcome of the Lebanese presidential selection has been oversold in some quarters as a big victory for Iran in its regional struggle against Saudi Arabia. The truth is more prosaic, complicated, and local.

None of the major political factions can justly be considered to have won outright, and the mind-numbing turns of the deal make clear that there aren’t any simplistic sides in Lebanon (or for that matter, in political life throughout the Arab region).

Political alliances in Lebanon—like in the rest of the region and the world—are in fact fluid and partial, by turn ideological and transactional.The anticlimactic election and the ongoing limping politics that are sure to follow make clear that no simple equation can reduce Arab politics to glib but ultimately misleading formulations, like those who lump together Shia, the Iraqi government, Hezbollah, Iran, and one Lebanese Christian faction into a single monolithic construct. Nor were Aoun’s opponents a unified bloc connecting Sunnis, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Syria’s opposition.

In short, the messy deal for Lebanon’s presidency, while hardly a triumph for any single idea or movement, provides a sharp reminder that politics and negotiation continue to play a key role in forging paths forward in a region where violent contestation of power usually grabs most of the attention.

All Politics Is Local—and International

The decision of Lebanon’s parliament to bless the Aoun deal says as much about the evolution of Lebanon’s model of power-sharing-cum-paralysis as it does about the region’s increasingly interwoven struggle for influence. On Monday, the Lebanese parliament—itself an arguably illegal body because it extended its own mandate—ratified a backroom deal to make Aoun president and down the road, to give the prime minister’s job to his rival, Saad Hariri.

This same deal was floated in 2014 after the previous president’s term expired. Back then, supporters of Hariri believed that Sunni rebels might win the Syrian civil war and that political tide in the region would shift, empowering them to sweep to power rather than accept the middling share of it they already possessed. Hezbollah and its allies, meanwhile, were content to muddle forward without a president at all, since they held the position of primus inter pares among Lebanon’s factions and stood to gain nothing important from a functioning executive branch.

After twenty-five months, only the expectations of the major players have changed. Hezbollah is willing to accept a president who, after all, was its candidate, if only to escape domestic blame for leaving the state in limbo. And the weakened party of Saad Hariri, facing fragmentation among its Sunni base and fading confidence from its Saudi sponsors and financial backers, has grown desperate. Hence it was willing to accept any terms to put its man back in the premiership, without any accompanying concessions that would boost its electoral chances later on or award it a bigger share of public sector spoils to loot.

Much went into the Aoun deal, most of it concerning Lebanese internal dynamics. Longtime rival Christian warlords Aoun and Samir Geagea made peace with each other earlier this year, realizing that the country’s Christian minority was losing even more relevance if it remained split between pro-Sunni and pro-Shia factions. Hariri struggled to maintain his position as his family company went bankrupt and Saudi Arabia, briefly but flamboyantly, hung him out to dry—canceling a grant to Lebanon’s military and standing by as its man in Lebanon, Hariri, was humiliated in municipal elections this spring.

In the view of his Saudi sponsors, Hariri had not done enough to stop Hezbollah and Iran from dominating Lebanon, so he deserved a comeuppance; that, according to Saudi watchers in Lebanon, was the message the Saudi royal family wanted to send this past year. But they realized that theatrical shows of pique do not wise policy make, and that by cutting off Hariri they made it easier for Hezbollah and Iran to conduct their political business in Lebanon. In the end, Lebanon mattered to the Saudis more than they initially thought.

It also ultimately turned out that Lebanon had some say over its own choice of leader. Aoun is not a president built and chosen by foreign powers, or at least not 100 percent so (his followers like to say that “the General” is 100 percent “made in Lebanon,” which exaggerates the point in the other direction).

Aoun formed a tight political partnership with Hezbollah in 2006, a surprising move at the time for a leading Christian warlord who had made his reputation by going to war against Hezbollah’s patron Syria in 1989.

But Aoun is not purely Hezbollah’s man, which is one reason why Hezbollah was willing to wait so long to help him get elected by parliament.

The General is considered unpredictable, headstrong, vain, ambitious, and a bit mad. Those are the characteristics which lead his most ardent admirers to see him as a charismatic leader and his enemies to fear him as unpredictable and prone to authoritarianism.In office, he will polarize and hector. Already in his inaugural speech on Monday he made chauvinistic, unfulfillable promises to try to send some of the 1.5 million-plus Syrian refugees in the country back home. He vowed to defend his nation against terrorists and Israel, to strengthen the military, and a cleaner government. But he will be hemmed in by Lebanon’s dysfunctional political power-sharing system, which his election does nothing to change.

Low Expectations

Given the tradition of painstaking and painful political negotiation in Lebanon, it might take a year, even two, for Saad Hariri to form a government and take office as prime minister. By then, new parliamentary elections will be underway. No one in Lebanon expects the state to function like a state any more than it has during the last five years of permanent crisis during which electricity, education, and health care have been in scarce supply, but graft and uncollected garbage have risen to historically high levels.

Events in Lebanon are not solely a byproduct of regional competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Nor can they be read simply as a fight between Shia Hezbollah and the Sunni Future Movement.

It is instructive to remember that initially, two sectarian Muslim factions, the Sunni Future Movement and Shia Hezbollah, were negotiating over the outcome of the most senior post in Lebanon still reserved for Christians; in Lebanon’s sectarian political game, the Christians had largely sidelined themselves from their own remaining political fiefs. Eventually, intra-Christian competition made a greater number of Lebanese warlords relevant: not exactly a step toward democracy, but new alliances between Christians kept an oligarchy from sliding into a duopoly. Those who describe Aoun’s victory as a win for Iran should reckon honestly with the fact that the alternative candidate backed by Saudi Arabia was Suleiman Frangieh, a Christian warlord whose fealty to Damascus, Hezbollah and Iran is far more ironclad than Aoun’s.

In a region where the local, regional, and international all interact, Lebanon’s presidential crisis embodied all three levels, and its resolution offers one image of how plodding, incremental, and frustrating it is to seek progress on any level at all.

On Monday, Lebanon moved one step away from the abyss of total paralysis. It is, however, hardly any closer to restoring a state that can manage anything remotely resembling governance.

It might not seem like much, but the Lebanese system has managed one feat that can allow its citizens, however modestly, to maintain their claim to provide a model for regional politics: against considerable odds and obstacles, many of their own making, Lebanon’s politicians have pursued political compromise by nonviolent means. That’s no small feat.

The Case for a More Robust U.S. Intervention in Syria

[Policy brief for The Century Foundation]

The United States can do more to achieve a political settlement—invasion and containment aren’t the only options.

• In its sixth year of war, Syria has reached a breaking point. Soon its remaining institutions will collapse and Syria will be a failed state. The United States has pushed hard for a diplomatic solution and intervened militarily on the side of rebel groups, but stopped short of action that could shift the conflict’s momentum. Meanwhile, Russia has intervened decisively on the Syrian government’s side.

• The human toll of the war has been catastrophic. Nearly half a million people have been killed and half the country’s population displaced, including 5 million refugees. War crimes are endemic. Civilians routinely suffer starvation, sieges, torture, extrajudicial detention and indiscriminate bombardment.

• Preserving Syria is a vital national security interest for the United States. If it doesn’t do more now, America and its allies will suffer even more of the consequences of an imploded state in the heart of the Middle East: jihadi attacks from the Islamic State and its ilk, a global refugee crisis, and violent militancy seeping deeper into every country on Syria’s borders.

• A robust U.S. intervention would expand Washington’s existing approach, which integrates humanitarian aid, diplomacy and military force, but needs much more of each to succeed. Washington should use military force to protect vetted opposition groups and curtail war crimes committed by the government in Damascus.

• Now might present a final opportunity. Russia and the United States have a rare overlap of interests. Syria’s war won’t have any neat outcomes; this conflict can only be managed, not won. A robust intervention will not bring an immediate end to the war, but could set the stage for an eventual political settlement.

• A forceful U.S. escalation now can preserve American interests and credibility and curb the worst excesses of the current violence, giving Syria a fighting chance of emerging from its civil war with intact institutions and a government that can represent every major group.

A nation exhausted: Portraits of Syria

After Eid I spent ten days in Syria, doing my best to collect as many individual impressions as I could. Everything about the trip was limited, but I was lucky enough to have many people share some part of their stories on what was ultimately a very fragmentary, kaleidoscopic, picaresque jag through government-controlled Syria on an itinerary and schedule largely not of my own design. And yet, the human stories seep through — even in these amateur snapshots I made with my phone. These images offer but a sliver of perspective. Yet still I believe they’re worth scanning through, to catch a glimpse of quotidian life.

Inside Syria: Q & A with TCF

I visited government-held Syria in October at a pivotal moment, gaining a rare glimpse into the part of the country still controlled by President Bashar al-Assad. The Century Foundation, where I am a fellow, asked about my impressions.

Q: What timing—the week you arrived, Russia unleashed its new military campaign. How did that change the outlook of the people you spoke with?

A: Russia came up in almost every conversation I had, whether with officials, fighters, or regular citizens. The war has dragged on for nearly five years, and whatever they claim, most people in Syria understand that it’s a stalemate that neither side is likely to win outright. For people living in government-controlled Syria, the Russian intervention has—for now—lifted the sense of fatalism. With Russia boldly on Bashar al-Assad’s side, the thinking goes, maybe the Syrian government can win outright. That’s created a palpable wave of optimism. Many people in the coastal cities of Tartus and Latakia told me they thought the war would now end within a year.

Q: Do you think it can end so quickly?

A: I doubt it. Russia’s move has completely shifted the geopolitics of foreign intervention and imposed new constraints on the United States and its allies. But most of the Syrians fighting against the government consider themselves patriots and are fighting on their own home ground. Contrary to Syrian government propaganda, which paints the rebels as foreign fighters and mercenaries, most of them are actually locals who prefer to die rather than surrender. Even if the government can defeat them with the massive push it has received from Russia and Iran, it will take a long time—probably two to five years—before they can reconquer the main rebel strongholds. And the buoyancy among government supporters (or even those who just want the conflict to come to any sort of end) will fade when they see that the rebels fight back, and that foreign interventionists on the rebel side can keep the fight going for a long time just by maintaining supplies of money, ammunition, and weapons.

Q: You had not visited Syria since 2007. What were the biggest differences that you noticed?

Government-controlled Syria feels beleaguered and utterly militarized. Assad’s Syria was always a heavy-handed police state, with intelligence agents everywhere and a huge web of agencies that detained people, tortured them, and kept them in fear. Today, the government has lost a great deal of its resources, holding maybe one-third of the country’s territory and controlling half or less of its remaining population. Yet, it retains its old heavy-handed style, and the displaced people living in the government areas are terrified of saying anything that might be construed as subversive.

Damascus is a beautiful city, and it was clean and well-run in 2007. For all the shortages today, it’s still functioning, but there are constant power cuts and real shortages of personnel and certain imported goods. There are checkpoints everywhere, and most of the men under 40 are either in uniform or are off-duty fighters.

Q: What was most on people’s minds?

A: In addition to the Russians, almost everyone I met openly talked about emigrating. They were either saving up to take a smuggler’s boat to Europe, didn’t have enough money but were desperate to raise it, or had considered it and postponed their decision point because of family reasons. Some said outright that they saw no future in Syria even if and when the war resolves. “It will take ten years to end the war, and god knows how long afterward to restore the country,” one pro-government militiaman told me. Most the people who have either left Syria this summer or plan on leaving are young, with careers ahead of them, or have children for whom they see no prospects inside Syria. Many of the people who have remained in Syria by choice retain the option to flee anytime because they have money or a second a passport, or they already have sent their children abroad and have remained in Syria because of their jobs or businesses. Antique dealers in Old Damascus would ask me if I thought it was a good idea for them to sell their shops at fire-sale prices to smuggle their kids to Europe. Off-duty soldiers driving taxis at night asked me how much it costs to get from the island of Lesbos to Germany. Getting out is the ubiquitous fixation, more even than what will happen in the war.

Q: Why were you able to visit Syria now? How closely were you monitored?

A: The government slightly opened the door over the summer to Western reporters. Perhaps they think they have a good story to tell now, about a government that is secular and protects minority rights defending itself against rebels whose strongest contingent is dominated by Islamic fundamentalists. Maybe they’re newly confident that they’re winning, with the support of their allies and the absence of meaningful American action.

When I traveled outside Damascus, a government official from the ministry of information accompanied us on our interviews. Sometimes there were also minders from the military or intelligence services, although some were vague about their affiliations. After working hours, I was free to move around Damascus unfettered.

Q: What’s the most important thing Americans should know about government-held Syria?

A: That’s a tough question because there is a lot that is important to know but impossible to assess, such as how deep the support for the government runs among the remaining population. But two key points surfaced again and again on this trip. First, Assad’s government has not changed any of its fundamental ways, in terms of how it runs the country, stifles dissent, and is completely uninterested in changing the nature of its system. And second, many Syrians who don’t particularly care for Assad’s way of running the country, who in fact fear the president, also fear the rebels on the other side, whose vision they find sectarian, intolerant or even nihilist. That middle ground of public opinion is still not free to speak on the regime side, but they could hold the key to a future Syria that reflects something freer and less corrupt than Assad’s government, and at the same time less sectarian and extreme than the jihadists on the opposition side. The war in Syria, sadly, looks like it might go on for another decade.

Confronting the “Moscow Track” for Syria

Issue brief for The Century Foundation. Download PDF.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is scheduled to address the UN General Assembly on September 28, on the heels of a shrewdly publicized deployment of new Russian troops and military equipment to Syria. Simultaneously—and not for the first time—the Kremlin has rolled out the prospect of a “Moscow Track” to peace in Syria, marketed as a pragmatic alternative to the failed U.S.-run Geneva Process.

Moscow’s latest moves have begun to shift the ground, and ultimately the United States will have to choose between two different, equally messy courses: standing aside and letting Russia and Iran shape the conflict unimpeded; or making a real diplomatic and military commitment in the hopes of influencing the Syrian civil war’s final disposition.

Already, a chorus of analysts and political actors is advocating a “hold-your-nose-and-make-a-deal with Russia” approach,1 claiming the United States must either sign on to Moscow’s plans against ISIS, or else plead guilty to promoting terrorism through American inaction.

But framing the choice as a binary one plays into the rhetoric of Bashar al-Assad and his sponsors, and ignores the fact that substantial American action can still reshape the dynamics and alter the outcome, just as surely as decisive Russian, Iranian, and Syrian moves could. The more time passes, however, the fewer options remain for the American camp.

Until President Obama decides to invest in a new Syria policy or else completely relinquish any stake in the conflict in the Levant, there’s little to discuss with Putin. Russia comes to the table with clear aims and a plan to achieve them; the United States needs its own goals and strategy before engaging in a conversation.

The most effective approach for the United States right now would be to quickly commit to a program that supports alternatives to Assad and opposes ISIS—while making clear that America would back peace talks that include all foreign sponsors and all domestic players in the conflict, with the exception of ISIS and other jihadis.2

This brief argues that such an approach is an essential precursor to any “Moscow Track” for Syria, and could well render it obsolete. It lays out where American and Russian interests in Syria overlap and where they diverge, and examines the limits of Russia’s going it alone. Finally, it outlines a course of U.S. action that would expand the options for the Syria crisis beyond the limited and troublesome alternative solutions currently under consideration.

Russia’s Interests—and America’s

Syria is Russia’s most solid foothold in the Arab world, and offers a strategic alliance, military contracts, and a critical naval base in Tartus. So, in the short term, Russia’s ramp-up is only an increase in the degree of Moscow’s long-running commitment to the regime of Bashar al-Assad.3 Many foreign and domestic constituencies are also influencing the course of Syria’s war. Arab monarchies in the Gulf, along with Turkey, have kept alive a Sunni-dominated insurgency that has fought the regime and its backers to a stalemate. The fighting has catastrophically crippled the nation’s institutions and infrastructure.

If the United States does not respond to Russia’s latest move with a concrete shift in policy soon, it will effectively cede the theater to Damascus, and its patrons in Iran and Russia. Eventually, momentum could shift in the regime’s favor. If Russia solidifies its presence in Syria further and installs better air defenses, the United States will no longer be able to easily consider pivotal interventions, such as establishing a no-fly zone.

Not all of Russia’s interests and intentions in Syria conflict with those of the United States, however, and in fact several overlap:

- Moscow and Washington abhor jihadi extremists and are obsessed with protecting their homeland from terrorist attacks.

- Both fear “blowback” from movements they have fought abroad.

- Neither power likes a power vacuum in a strategically sensitive Middle East; despite Washington’s looser rhetoric, both powers are fundamentally conservative about regime change.

- Both want to preserve the institutions of the Syrian state and keep its borders intact at the end of the current civil war. In fact, both powers are invested in the existing Arab state system and do not wish to see the emergence of new states or the redrawing of borders.

But a number of crucial differences separate the two powers:

- While Russia sees Bashar al-Assad as a solid partner, the United States sees him as a long-term strategic threat who cynically allowed jihadis to flourish in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, and backed militant groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas.

- Russia supports the Iran-Syria alliance and an arc of anti-American regimes and non-state actors from Tehran to the Mediterranean. For obvious reasons the United States sees that alliance as a threat to its hegemony in the region and to the rough alliance of U.S.-allied Arab states.

- Russia and the United States are at loggerheads elsewhere: over the Ukraine, energy supplies to Europe, and the Iranian nuclear program.

- The two powers exhibit vastly different levels of willingness and capacity to fight ISIS.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Russia has much more narrow and easier to fulfill strategic aims: shore up a local client dictator, preserve a military foothold, and dent jihadist capabilities. The United States on the other hand has a wide range of hard-to-reconcile regional aims; and for all its equivocation, Washington’s aim is to stabilize the region. It does not have the luxury and clarity of a spoiler’s agenda.

What Can Russia Actually Achieve?

Much of Washington’s reaction to Russia’s surge has been devoid of context and long-term perspective. Of course, an injection of Russian fighters and equipment will change the dynamics of the fight; but there is no evidence that Russian intervention will have a conclusive impact. By way of comparison, a considerably larger U.S. occupation force in Iraq was unable to eliminate Al Qaeda in Iraq, the Islamic State’s precursor. And the Soviet Union’s attempt to decisively shore up a local partner against jihadi rebels—in Afghanistan in the 1980s—failed mightily.

Russia and Iran both benefit from an inflated reputation in Syria. Both powers have spent considerable funds and manpower to prop up a regime that has steadily lost ground during four years of war. Betting on the regime has been costly, and Russia’s decision to double down exposes it to still greater risks and costs. It will take time to see whether Russia is engaging in a limited and achievable intervention—striking ISIS while shoring up the regime’s heartland—or a more far-fetched all-out venture to win the war outright for Assad.

Syria’s dynamics are unique, of course, but there is no sound reason to predict Russia can wipe out the anti-Assad rebellion as it now stands. Foreign influence has shaped the Syrian war for years—through the limited impact of previous gambits in Syria by the United States, Iran, and the Arab Gulf monarchies—but has not been able to decide its outcome, underscoring the need for modest Russian expectations.

Russia and Iran together can probably assure that their local partner in Damascus remains in power over some portion of Syria, but it is less clear whether they can re-extend Assad’s ambit beyond the rump state he controls today. It is even less clear what will survive of Syria’s national institutions. And there will surely be blowback. Fighters from Chechnya and other former Soviet republics already are fighting with the Syrian rebels. Their ranks are almost guaranteed to swell now that Russia has publicly upped its ante in Syria.

How Should the United States Respond?

Until now the United States followed a wishy-washy course, typified by the “non-strike event” in the summer of 2013,4 when Washington backed down from its threat to intervene against Assad’s use of chemical weapons.5 Once America abandoned its fixed red lines,6Washington downgraded its already limited leverage over the conflict, while remaining vulnerable to its consequences. Ever since, the major players in Syria have vastly lowered their expectation of any U.S. involvement whatsoever, whether political, economic, or military.

The United States wants Assad gone, but has done little to hasten his fall because the available options to replace him are poor. Washington wants “moderate” rebels, but also does not want to get dragged into a civil war. As a result, it has not given any meaningful support to any militia that has a serious combat presence, and it has not exercised any political or military muscle that would change the balance of power on the ground.

At times, Washington has even appeared to believe that a quagmire in Syria would somehow serve U.S. interests by draining the resources of a gang of bad actors: Iran, Hezbollah, Assad, Russia, the money men in the Arabian peninsula, ISIS, and Al Qaeda.7Counterterrorism officials seemed to believe that the threat from ISIS was local, and could be bottled up in the Levant without any blowback beyond Syria’s borders.

All the assumptions underlying American inaction, however, were blown apart by a series of cataclysmic events: the concurrent implosion of Syria and Iraq in 2014 at the hands of ISIS, followed by the entrenchment of a sustainable jihadist empire headquartered in Mosul, and finally a human wave of displaced people remaking the demographics of Syria’s neighbors and flowing through Europe. No matter how hard the U.S. government has tried to contain, cauterize, or ignore the Syria war, its strategic ramifications continue to demand notice.

Putin’s showmanship has once again created a sense of urgency, just as the refugee crisis, the emergence of ISIS, and the use of chemical weapons did in early periods of the war. In response, some analysts and politicians in the United States have focused on the public relations fallout from Russia outmaneuvering Washington.8 In the case of Syria, that image reflects reality. Russia is achieving its admittedly simpler, Machiavellian goals far more successfully than the United States because Russia is far more committed, has dedicated far greater resources, and has a solid ally in power in Damascus.

If, after all the political calculations are made, the United States is unwilling to shoulder the risks of a heavier involvement in Syria, then it must make a clear case that inaction is a safer, smarter, and more responsible course than intervention. It must argue that any greater military involvement would make the human toll worse. And if it decides to pursue inaction and still wants to maintain some semblance of its role as a humanitarian world leader, the United States must also make a serious production of spending money and resources to contain the wider fallout of the conflict in terms of contagion and refugees. Washington has led international donations to the Syrian refugee response and insists it is a priority, but American contributions have been inadequate to address the crisis. United Nations appeals remain massively underfunded, and millions of refugees live without any secure status in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. If the United States decides to limit itself to addressing the humanitarian needs, it must immediately commit to resettling a number of refugees in the six figures, and ought to commit enough money to fully fund the UN’s Syrian refugee appeals.

A better course of action would be to get off the fence and aggressively pursue a plan that promotes an inclusive national solution to the Syrian conflict, one that would address core concerns about governance, corruption, and the disenfranchisement of many Sunnis.

Such a course would be fragile and full of risks, but the alternative is worse: a de facto alliance with Putin, Assad, and Tehran in shaping the future of Syria. In that scenario, the very same parties that drove Syria to collapse and green-lit the unfurling of a massive international jihadi wave would dictate the terms of a counter-jihad, with the United States playing a supporting role. An American junior partnership with Assad and Putin would be bad geopolitics for the United States—and it also would be unlikely to bring peace to Syria.

What would a more effective solution look like? The United States cannot wisely sign onto an anti-ISIS alliance composed solely of Assad, Russia, and Tehran. A genuine anti-ISIS campaign must have support from Syrian Sunnis if it is to have any chance of success. A national coalition backed by all the major non-jihadi players would be the only viable vehicle for fighting ISIS and stabilizing Syria as a whole. It would be a long shot—and it would become a possibility only if the United States decided to provide a significant counterweight to the Damascus-Moscow-Tehran alliance.

That position would entail a serious and major U.S. commitment, including a no-fly zone and safe havens, and partnerships with any non-jihadi militias willing to rhetorically embrace basic values of pluralism and shared governance.

Crucially, this American involvement must be accompanied by a new diplomatic initiative from Washington, inviting all the conflict’s foreign sponsors and all its domestic stakeholders—except for the jihadis—to take part in designing and supporting a transitional government. Assad and his circle would have to be part of that negotiation.

Talking to Putin about Syria will not make America look more ineffectual and disconnected than it already does. On the other hand, there is no reason to start a dialogue unless the White House has something to say. Articulating and putting resources behind a regional strategy to resolve the Syrian problem would be a good opening statement in any conversation with Russia.

Notes

1. Dmitri Trenin, “Like It or Not, America and Russia Need to Cooperate in Syria,” Carnegie Moscow Center, September 17, 2015,http://carnegie.ru/2015/09/17/like-it-or-not-america-and-russia-need-to-cooperate-in-syria/ihuf.

2. Thanassis Cambanis, “A Plan for Syria,” The Century Foundation. July 28, 2015, http://tcf.org/work/foreign_policy/detail/a-plan-for-syria.

3. Borzou Daragahi and Max Seddon, “This Is What’s Behind Russia’s Push Into Syria,” BuzzFeed News. September 16, 2015,http://buzzfeed.com/borzoudaragahi/this-is-whats-behind-russias-push-into-syria?utm_term=.hxEzEKAKj5#.am50r2PlPE.

4. Patrice Taddonio, “‘The President Blinked’: Why Obama Changed Course on the ‘Red Line’ in Syria,” Frontline, May 25, 2015,http://pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/foreign-affairs-defense/obama-at-war/the-president-blinked-why-obama-changed-course-on-the-red-line-in-syria/.

5. Mark Landler and Jonathan Weisman, “Obama Delays Syria Strike to Focus on a Russian Plan,” New York Times, September 10, 2013, http://nytimes.com/2013/09/11/world/middleeast/syrian-chemical-arsenal.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

6. Josh Rogin, “Syria Crosses Obama’s New Red Line,” Bloomberg View, March 19, 2015,http://bloombergview.com/articles/2015-03-19/syria-s-chemical-attacks-cross-obama-s-new-red-line.

7. Thanassis Cambanis, “How Do You Say ‘Quagmire’ in Farsi?” Foreign Policy, May 13, 2015,http://foreignpolicy.com/2013/05/13/how-do-you-say-quagmire-in-farsi; and Thanassis Cambanis, “Should America let Syria fight on?” Boston Globe, April 7, 2013, https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/04/06/should-america-let-syria-fight/UUtDpctZYyeymgSjgRSBWK/story.html.

8. Jonathan Broder, “Can Putin Save Assad in Syria?” Newsweek, September 16, 2015, http://newsweek.com/russia-syria-isis-putin-obama-assad-372864.

A Plan for Syria

Issue brief for The Century Foundation. Download as pdf.

With the Iran nuclear negotiations concluded, attention ought to shift to a political solution for the troubling war in Syria, which has killed about a quarter-million people (estimates range from 230,000 to 320,0001), while displacing 4 million refugees into the Levant and Turkey.2

The United States remains an indispensable source of influence in the Middle East—when it chooses to get involved. It can shift the dynamics of the Syrian civil war by taking two steps. First, Washington should pour a new, higher level of support into the northern front of the civil war, in coordination with key allies, including Turkey and Saudi Arabia. Second, it should continue to promote an end to the war through political negotiations that include all the key domestic and international actors in the conflict and exclude only the most extreme jihadist rebels.

A sustained intervention through proxies on Syria’s northern front would be a messy and inconclusive affair, but if carefully tailored, with pragmatic expectations, it could completely shift the political horizon for the Syrian civil war. No foreign intervention can create an idealistic group of democratic, secular rebels ready to take over the entire country of Syria and replace the regime. With international support, however, it is possible to create a coalition of nationalist rebels capable of making gains against both the regime in Damascus and jihadist extremists, including ISIS, the Nusra Front, and Ahrar al-Sham. An invigorated nationalist opposition could provide the final incentive needed to bring Syria’s combatants into a productive negotiating process.