Iran’s Edge

Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps in a military parade marking the 36th anniversary of Iraq’s 1980 invasion of Iran, in front of the shrine of late revolutionary founder Ayatollah Khomeini, just outside Tehran, on Sept. 21, 2016. AP PHOTO/EBRAHIM NOROOZI

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

The decision by President Trump to decertify the Iran deal and impose sanctions on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps marks the public debut of a campaign that’s been underway since the spring, when Trump ordered his national security team to find ways to “roll back” Iranian influence.

As we’re likely to see over the coming year, Iran has cultivated its own options to throw nails and bomblets in the path of any presumptive American juggernaut. It might be possible to roll back Iran’s reach in the Middle East, but not without painful costs, which can be visited on a web of American targets and allies located throughout Iran’s sphere of influence.

According to Middle East experts who have consulted privately for the administration on Iran policy, the president asked for ways to raise the price for Iran of its expansionist policy in the region — without exposing America to direct new threats. That might not be possible.

After a decade during which America tried to balance the regional contest between Iran and Saudi Arabia, with its deepening Shia-Sunni sectarian inflection, Trump has cast his lot with one side. When he placed his hands on a glowing orb in Saudi Arabia, he overtly endorsed an all-Sunni gathering whose primary purpose was to counter Iran in the region.

We’re about to witness a real-life test of an Iran policy that eschews diplomacy and embraces confrontation. Trump and his advisers have described their volte-face against Iran in terms of deterrence theory, which attempts to put a scientific gloss on how threats of war play out between two nuclear powers capable of mutually-assured destruction.

But it’s not deterrence theory that offers the best guess of what the coming escalation with Iran might look like, it’s the gritty modern historical record.

During America’s messy occupation of Iraq, militias trained and funded by Iran were able to pose the most sustained military challenge to US troops. Sophisticated bombs called “explosively-formed penetrators” were able kill Americans even in the US military’s best armored vehicles. US officials believed that Iran provided these weapons and the training to use them — but kept their hands off the operations so they wouldn’t provoke a direct conflict.

Late in his final term, in 2007, President George W. Bush slapped a foreign terrorist organization designation on the elite Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, but stopped short of designating the entire armed forces, a move which Iranian leaders have said they would consider an act of war. Around that same time, some American officials were musing publicly about preemptive military strikes on Tehran’s nuclear program.

Then, as now, Washington was exploring a wider escalation with Iran while also probing for ways to prick Iran in regional flashpoints. One apparent pushback saw American troops detain five Iranian employees at the consulate in the Iraqi city of Erbil.

In that heated context, a remarkable raid took place on January 20, 2007. Militiamen in American uniforms, driving a convoy of SUVs identical to those commonly used by US troops and contractors, sped into an American facility in Karbala. They were inside before guards noticed anything amiss. They spared the Iraqis on the base, targeting only Americans, and managed to kidnap five soldiers who were later killed by their captors.

Evidence later emerged connecting the attack to Iran; not conclusively enough to justify direct retaliation by the United States, but enough to leave another bruise, and another argument that America couldn’t tangle with Iran cost-free.

Officials and analysts around the Middle East have speculated for years about where Iran might begin striking back against American interests if the two nations came to blows.

The Karbala raid suggests what Iran is capable of. In recent statements, commanders of the IRGC have warned that American installations could be targeted anywhere within 1,250 miles of Iran’s borders — the range of Tehran’s conventional missiles.

But a direct strike would engulf Iran in a direct war with the United States in which it would be at a great disadvantage. History suggests that Iran’s leadership prefers indirect conflict, with all the advantages of asymmetric warfare and plausible deniability. And there are a plethora of American targets in the Middle East that are exposed to Iranian-linked malefactors who could strike with weapons much more basic, and less traceable, than a long-range missile.

Today there are more than 5,000 American troops stationed in Iraq. Meanwhile, Iran’s regional relationships have grown deeper and broader. Along with its long-time militia allies, including foreign groups whose members spent the 1980s and 1990s in exile in Iran, today there are tens of thousands of new militiamen actively trained and advised by Iran. They are part of the Popular Mobilization Forces created to fight the Islamic State, or ISIS. Many PMF units are directly under Iran’s control but fought hand in glove with the United States in the campaign against ISIS.

Today, some of those same PMF militia fighters are embroiled in a dangerous confrontation with Kurdish Peshmerga forces around Kirkuk.

A quick perusal of Iran’s reach and alliances lends credence to what longtime Iran watchers argued: Iran does best in a regional proxy war. According to this analysis, Iran has little incentive to break out to a nuclear weapon, or fire the long-range rockets it already has developed, while it has every incentive to magnify its ability to destabilize and threaten rivals with indirect attacks by groups it supports: acts of sabotage, terrorism, and proxy warfare. (Supporters of the Iran nuclear deal argued that Iran’s penchant for indirect warfare meant it was never likely to pose a nuclear threat even if it did acquire a weapon, while critics said it underscored the destabilizing danger of Iran’s unchecked spoiler tactics.)

Examples abound, from the campaign of hostage-taking in Beirut in 1980s (mostly conducted by Hezbollah, but clearly at Iran’s direction), to the creation of proxies in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq, to support for hyper-sectarian politics across the Levant and the Arabian peninsula. Sure, other regional powers like Saudi Arabia have used the same tactics, but to far less effect and usually not in direct opposition to US interests (at least when it comes to state-orchestrated violence; terrorist blowback and a permissive environment for terrorism are another matter entirely, and the reason why a sounder policy from Washington would entail containing Saudi Arabia as well as Iran.)

Status quo powers like the United States, Russia, and China, even when they are competing for influence, share a common interest in unified, effective state structures. They like to do deals (for oil, weapons, or other commodities) and build alliances with unitary governments that have a clear leader and functional institutions.

Iran, by contrast, has done well in the Middle East when its neighbors are too weak and fragmented to pose a threat. The Islamic Revolution almost collapsed during the war with Saddam Hussein in the 1980s. Iran’s leaders concluded that their best bet was to cultivate unstable, fragmented, and squabbling neighbors who couldn’t pose such a threat. Iran has mastered better than any other intervening power the tactics of jockeying for influence in a kaleidoscopic, unstable war zone with dozens of competing militias and power centers.

While other powers have struggled to maintain toeholds in shifting environments like Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, the security apparatus of Iran has built thriving spheres of influence; its operatives are comfortable working with multiple, even dozens, of proxies, warlords, and local allies. The Iranians are able to hedge their bets and extend their influence in these fragmented zones of authority not because they are evil geniuses, but because their goals are different and easier to achieve.

Furthermore, the Iranians have a home-court advantage – their stake in the Middle East can’t fluctuate like it does for faraway imperial powers. Tehran also has invested in a long game, without end. Many of its operatives spend their entire careers working in Iraq, Syria, or Lebanon; they speak fluent Arabic and build relationships over decades with their military, intelligence, and political counterparts.

They seek unimpeded military access to proxies, influence with governments, and access to markets — all goals easily achieved in a context of fraying state authority.

Needless to say, it’s easier to undermine and erode state institutions than to build them.

This skill set — honed in Lebanon since the early 1980s and then later in Syria and Iraq — translated easily to the war in Yemen that expanded two years ago. It most certainly will help Iran in a phase of renewed confrontation with Trump’s America.

What Did the Trump Administration Just Do in Syria?

[Published in The Atlantic.]

If the presence of such fighters in the area is confirmed, the airstrikes, and the likely military escalations to come elsewhere, may mark an end to a long period during which the United States avoided direct military clashes with Iran or Iranian-backed proxies. If U.S. troops are now engaging directly with Iranian militias, escalation in the absence of a well-wrought plan could inflame the conflict in Syria and further afield. On the other hand, for all Iran’s bluster, the Islamic Republic, a staunch ally of Syria, will have to re-calibrate its own expansionist ambitions in the Middle East if it encounters meaningful resistance from the United States after nearly a decade of only token or indirect opposition.

The stakes are high: Iran’s regional rivals have staked their hopes for a reversal of fortune on Trump’s willingness to embrace traditional Sunni allies and take military action against Assad, while Iran and its allies believe themselves on the verge of a total victory in Syria.

And while the strike may have been undertaken more in self-defense than as part of any shift in policy, the Trump administration has been actively seeking ways to repel Iran, canvassing the Pentagon as well as U.S. allies in the region for suggestions about where and how to draw lines against what it views as Iranian expansionism. American experts with experience in the region, and in the U.S. government, say they have been consulted about possible pressure points. In my conversations with senior Arab officials, they have shared their own proposals in detail. The strikes against Tanf may well suggest that America is moving out of the planning stage and into a period of military action intended to abate Iranian momentum.

So far, there are no indications that the Trump administration is doing any of the necessary groundwork to insure against blowback or out-of-control spiraling as America appears to turn from accommodation and containment to military force. The Obama administration pursued a cautious, conciliatory approach to Iran, avoiding any direct clashes in the belief that all other concerns were secondary to the nuclear negotiations, and that a relatively minor clash over Syria or Yemen could upend years of talks to freeze Iran’s nuclear program. In practice, the regime and its clients learned that they could behave as recklessly or maximally as they wanted in pursuit of their interests in the Middle East without fear of a robust U.S. response, even in places like Iraq. Obama administration officials say they believe this approach allowed them to win international support for the nuclear deal and to portray Iran, rather than the United States, as the problem party in the negotiations.

It’s just as likely that nuclear negotiations would have produced the same outcome even if the United States had pushed back against Iranian actions in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, prior to the conclusion of the deal. But once the nuclear deal was concluded, Obama made a poor choice, joining forces with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in an ill-planned campaign in Yemen that has hobbled the state, wantonly targeted civilians, opened new space for al-Qaeda, and strengthened, rather than reduced, Iranian influence over Yemen’s Houthi rebels. Meanwhile, he left Iran and its proxies a free hand in Iraq and Syria. The result today is a triumphalist Iran, whose allies and proxies can claim a dominant position in Iraq and Syria, and whose military and political rise was, in many instances, directly abetted by the United States.

The smartest bet (and the least likely one in a Trump White House) would avoid direct military clashes and instead use political pressure to marginalize Iranian proxies in Iraq, and military force against Iranian allies in Syria. It’s unrealistic to try to erase Iranian influence in the region, as the Arabian monarchs deluded themselves into believing they could do in Yemen. What is realistic is to deny the Iranians and their allies some of their goals, such as a swift victory over Syrian rebels in the south and southeast, while making other goals, like domination of Iraq and Syria, more costly.

Senior officials in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia (like most of their counterparts throughout the Middle East) have made no secret of their disdain for Obama, who they believe abandoned his traditional allies and, in general, neglected the turmoil that has engulfed the region. Now they are fully invested in Trump, a gamble that senior officials from the Gulf gleefully describe in private, and fully expect will pay off. They believe he will value the colossal support they give him by purchasing American arms and supporting global energy markets, and that in return, he will take their suggestions about how to manage regional security threats. The narrative they’re selling is seductively simple: The region faces a single destabilizing extremist threat, and the supposedly complex web of forces at play are really just different faces of the same phenomenon. Gulf envoys portray the Muslim Brotherhood, al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and even Iran, as different brands and incarnations of the same violent extremism—a simplistic and simplifying approach that leads to terrible policy prescriptions, but which comfortably echoes Trump’s tendency to vilify Islam.

Therein lies the danger. An inattentive and reactive administration in Washington that has decided it’s high time to stop Iran might fumble for whatever opportunities present themselves. An amped war in Yemen after a high-priced lobbying campaign by Gulf allies? Why not. A one-off strike against Hezbollah, Iraqi-Shia paramilitaries, or some other Iranian ally in Syria, so long as there’s no risk of hitting Russians? Sure.

But what happens when Iran and its allies, inevitably, strike back? They’ve been in this game for decades, and they are masters at bedeviling U.S. goals and striking against U.S. interests using a web of proxies and allies that are often difficult to connect directly to Tehran. Furthermore, as spoilers, Iran’s side often needs only to make a splash, not necessarily to win outright.

The best way forward would entail a systematic and contained series of strikes against targets of opportunity—protecting civilians and U.S.-backed rebels when possible, continuing to strike jihadists while denying cheap successes for the Assad regime, and, above all, exacting a military cost for atrocities and war crimes. None of these moves will expel Iran from Syria or diminish its status as a dominant regional power—a status it earned over many long decades of hard work as a spoiler, ally, proxy-builder, and kingmaker. While the United States swung in and out of the region and the Sunni royal families fell victim to their own lack of capacity as states with weak institutions and mercurial governance, Iran stuck with its long game. Successfully standing up to it today means restoring balance and halting its forward momentum.

Washington can learn a bit from Iran’s playbook. If the United States plans its strategy right, it doesn’t have to beat Iran and its proxies—all it has to do to shift momentum is make it expensive for Iran (by destroying some of its troops or proxies) and for once make a credible show of using air power to defend American allies on the ground. It can also, with minimal resources, prevent Iran and Assad from reclaiming Syria’s south and southeast in a cakewalk.

The Trump administration’s military moves in Syria could signal the beginning a concerted effort against Iran. But given the its anti-Muslim record, impulsiveness, and general chaos, it’s just as likely that renewed U.S. attention to the Middle East will mean military intervention without a sound strategy—and will spawn a new generation of problems rather than the solving existing ones.

We are the war on terror, and the war on terror is us

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

THE FIRST signs of America’s transformation after 9/11 were obvious: mass deportations, foreign invasions, legalizing torture, indefinite detention, and the suspension of the laws of war for terror suspects. Some of the grosser violations of democratic norms we only learned about later, like the web of government surveillance. Optimists offered comforting analogies to past periods of threat and overreaction, in which after a few years and mistakes, balance was restored.

But more than 15 years later — nearly a generation — we have not changed back. Shocking policies abroad, like torture at Abu Ghraib and extrajudicial detention at Guantanamo Bay, today are reflected in policies at home, like for-profit prisons, roundups of immigrant children, and SWAT teams that rove through communities with Humvees and body armor. The global war on terror created an obsession with threats and fear — an obsession that has become so routine and institutionalized that it is the new normal.

The perpetual war footing has led to a militarization of policy problems under the Trump administration. The share of recently active-duty military officers in senior policy positions exceeds the era after World War II, historians say. Border police chase people down outside homeless shelters and clinics, deport legitimate visitors, and swagger around airplane jetways demanding identification. And another burst of defense spending is just around the corner.

All of this is a sign that the United States has fallen into a trap familiar to many former colonial powers: They brought home their foreign wars at great cost to their democracies. Colonial Great Britain normalized inhumane treatment of civilians abroad in service of empire, and then meted out the same Dickensian abuse to the poor at home. In its futile effort to hold onto its colony in Algeria, France rallied anti-Islamic sentiment and pioneered indiscriminate counterinsurgency; as a result, to this day in France, religious freedom and suspects’ legal rights still suffer. Liberals in Israel argue that the practices necessary to perpetuate the occupation of Palestinian territory have fatally eroded the rule of law.

Indeed, the longer a conflict endures, the more deeply all parties to it are corrupted; citizens asked to misbehave on behalf of their country find they can’t stop when they return home or go off duty.

For more than a decade and a half, America has embraced a vast military campaign that relied on major shifts in US values and policies. A covert assassination program targets terror suspects with no judicial process. Many bedrock civil liberties have been traded away. Some initial excesses, like the use of torture, were curbed. But the norm is still inhumane forms of detention, and abuse that meets the definition of torture. Meanwhile, the United States has maintained what is for all intents and purposes an extrajudicial gulag in Guantanamo Bay since 2001.

Collectively, all these data points have struck with the force of a meteor against America’s culture of due process and institutional checks and balances.

As this new mindset took root, even some of its architects took notice — and were alarmed. Midway through Obama’s presidency, a White House adviser confided concerns about the executive branch’s “kill list” and accelerating use of drone strikes. “One day historians are going to excoriate us for the kill list, and they’re going to ask why no one questioned what we’re doing,” this adviser said.

We’re still waiting for that day. In the meantime, we must understand the full extent of the damage. America became its war on terror, abandoned its principles to visit horrific violence abroad, and then brought into domestic politics an ease with lawlessness, caprice, imperial-style occupation. A global war, by definition, must also be waged at home.

A sizable contingent today believes that the military solution is the only and best one for many problems, from terrorism to corruption to managing diplomatic relations. And while knee-jerk militarism is poisonous for a republic, we would do well to remember the failures of civilian politics that make even generals of dubious repute like David Petraeus seem like potential saviors.

“We’re pell-mell down a road that we don’t even we realize we’re on anymore because we’ve got so used to the military option,” said Gordon Adams, a professor emeritus at American University and co-editor of the book “Mission Creep: The Militarization of US Foreign Policy?”

It’s not that military officers are bad or necessarily wrong — it’s that they offer just one perspective on policy problems, and they’ve been trained to consider one tool: force. That’s well and good when military officers are in a room with other experts with other perspectives, debating how best to deal with Osama bin Laden. It makes less sense when military officers, active-duty and retired, are the only people in the room debating US policy toward Russia, China, the Middle East, or issues even further from their lane, like airport security and international trade. It becomes absurd when doctrines that failed so spectacularly in Iraq and Afghanistan somehow worm their way into local police departments in the United States.

Immediately after the attacks of 9/11, America’s political class decided its only goal was stopping future terror strikes. Legislators forsook legislative oversight. Courts were reluctant to limit metastasizing executive power. Rights were stripped by laws like the USA Patriot Act, which watered down protections against overzealous law enforcement hard won over a century. It’s not hard today to draw a line from the bullying jingoism of 2001, when opposing the Patriot Act reeked of disloyalty or treason, to the election of President Trump, and his reckless “America First” positions that jeopardize global security in 2017.

A bipartisan consensus views remote strikes against suspected terrorists as an efficient refinement on the early, labor-intensive, versions of counterterrorism. Although the rest of the world still musters outrage when civilians are killed, the issue has all but vanished domestically. There is simply no domestic political cost for accidentally bombing a hospital in Afghanistan, or killing 10 children in Yemen, or the deaths of dozens of civilians in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere. Think about the shock that the My Lai massacre caused to American politics less than half a century ago. Now consider the cultural shift whereby the public accepts and ignores routine massacres — usually committed with air power, and sometimes with a plausible claim that accidents were honest mistakes or not directly America’s fault or the victims were sympathetic to American enemies, if not actually guilty of anything.

This is a sea change. In the 1970s, when the Church Commission revealed that the CIA, sometimes with presidential support, had assassinated foreign leaders, it was a scandal. The uproar curbed the powers of the CIA for decades.

Compare that to the last 16 years; black ops are fetishized and widely supported. There are no checks and balances. The president can — and has — decided to assassinate terror suspects, including American citizens. Hardly anyone raises a peep except for the ACLU and a handful of other minor constituencies with a hard-line commitment to civil liberties. That’s how strange, and troubled, is our adoption of a heedless counterterror gospel. Obama seemed to order assassinations with such care and deliberation that criticism only came from the fringe; Trump critics will find it difficult now to object to a kill list on grounds not of principle but of personnel.

Afghan war veteran Brendan O’Byrne articulated this disturbing transformation in an essay this month in the Cape Cod Times. He likened the endless quest to kill terrorists to cycles of violent abuse inside families. As a troubled youth, he recalled, he attacked his father, who then shot O’Byrne in self-defense. “America is like my father, creating the very thing it has to kill before it kills them,” O’Byrne writes. “Where is our responsibility for creating the terrorists we are now fighting?”

America has confused self-defense with an impulse to kill “every possible threat,” O’Byrne continues: “We run the risk of becoming the very thing we claim to be fighting against — terrorism.”

Our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have stretched on so long they’ve become the fixed backdrop to a country at war against terror in more places than the average American can track. The Pentagon now operates in roughly 100 countries worldwide. To be American is to be at war.

“I’m teaching college students this semester — they can barely remember a time when these wars were not underway,” said Jon Finer, a former war correspondent in Iraq who later became chief of staff to then-secretary of state John Kerry. “Combat has become a normal, regular feature of American life.” Over a decade Finer switched careers, from journalist to senior national security official, only to find the American military still engaged in counterinsurgency with jihadis in the same provincial deserts of northern Iraq.

The war against terrorism aspired to reduce to zero the number of attacks on American territory — no matter how many attacks that would require America to conduct, and provoke, abroad.

A society that embraces war without end eventually stops recognizing that its initial adrenaline response is abnormal. Fear becomes the baseline. The mirage of zero-risk and the cult of war we embraced to find it have systematically warped our politics and society.

The extremes that led to Trump’s election — xenophobia, race-baiting, fear, disregard for rights — were nurtured by the many Americans mobilized to execute US foreign policy in the post-9/11 war zones. Military personnel, diplomats, aid workers, ideologues, apolitical contractors: Hundreds of thousands of Americans were steeped in war and brought that culture home. If you’ve learned one, brutal way to search cars at a checkpoint in Iraq, it’s hard to shift to the gentler methods when you’re working a few years later as an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent or police officer in middle America.

Trump’s America is our America, and it’s been taking shape for many long years. We won’t restore the balance and get the best of America back until we decide to end our war on terror and focus anew on the American rights that undergird our security even more than prisons and SWAT teams.

The perils of elected strongmen

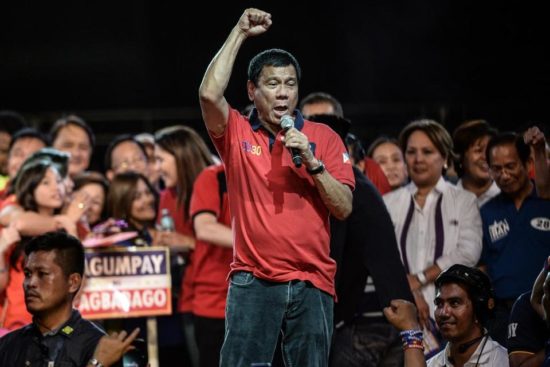

Rodrigo Duterte speaks to supporters during a campaign rally. MOHD RASFAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

FORCEFUL, FOUL-MOUTHED, and willing, by his own account, to try any policy that worked, Rodrigo Duterte seemed like a new kind of politician when he swept to power by a decisive margin in the Philippines last year.

Today, his brash, often toxic, approach offers an early look at a leadership style suddenly more in vogue, with Donald Trump’s victory in the United States and a crop of populist authoritarians waiting in the wings in democracies around the world.

There are differences between the budding strongman in Philippines and his peers in other countries. Duterte hails from a left-wing background and has decades of government experience as mayor of a provincial city. His thirst for power does not seem to be matched by a propensity for personal corruption.

Still, Duterte’s recipe holds some alarming lessons about what can happen when an authoritarian wins a democratic election and rules with contempt for the rule of law — but with the blessing of passionate popular support.

Duterte is willing to attack shibboleths and savage his critics. He’s trashed the media and suggested that his most outspoken Senate critic kill herself. He approaches running a nation of 100 million people like a bigger version of being a mayor for whom there’s no coequal branch of government. However much these tactics endear him to voters who are fed up with conventional politics, they also erode the unwritten political norms that make a democracy work.

Duterte’s brief but already searing record in office demonstrates how quickly an elected leader can undermine the institutions of democracy and begin to transform a state. It also shows that, when aspiring leaders make extreme promises, we should take them at their word. We should pay attention to the devoted crowds who applaud them, and we should take seriously the threat they pose to democracy.

IT WAS ONLY AFTER its “people power” revolution in the late 1980s that the Philippines became a modern democracy — after a bloody century that included some genuinely contested elections but also decades of dictatorship and a lengthy American military occupation. The democratic experiment has been shaky but also pathbreaking.

The nonviolent popular movement that overthrew dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1986 presaged the European revolts that brought down the Iron Curtain a few years later. For years the lone democracy in Southeast Asia, the Philippines provided moral and sometimes practical support for liberalism and pluralism elsewhere in the region. With no-holds-barred politics and a large population, the Philippines showed that even a rowdy and flawed democracy could stand in the way of authoritarian rule.

For a time, the Philippines looked like a promising regional barometer. By 2009 neighboring Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and East Timor had followed its lead, scoring as “free” or “partly free” by Freedom House.

Once again, the Philippines seems to be leading a political trend — this one not so positive. Democracy and reforms have regressed in Thailand and Malaysia, and Duterte ran a fiery campaign as much against the inefficiencies of democracy as against his opponents.

Fledgling democracies have not instantly solved poverty, crime, and other problems left over from decades of authoritarianism. Some countries whose democratic transitions have fared better, like South Korea, pair stable politics with rising levels of prosperity and development. But the theory that democracy and national wealth grow in tandem — popular among some political scientists — has been contradicted not only by the success of democracy in India, despite continuing poverty, but also by the surge in authoritarian politics in rich Eastern European countries and, now, America.

Duterte tapped into specific grievances about corruption, crime, and drugs, but also into a wider global malaise about the methodical approach to government that so many countries have pursued. He sold himself as a rough-talking straight-shooter, unconcerned about the feelings of a political establishment he viewed as self-serving and corrupt.

He won the May elections handily, 15 percentage points ahead of his nearest competitor. Crude comments about rape and an open contempt for civil liberties appeared to only help his campaign. Soon after his June 30 inauguration, Duterte shook things up at every level. He called President Obama a “son of a bitch” and the pope a “son of a whore. (He later apologized for the latter comment, which provoked outrage in the overwhelmingly Catholic Philippines.)

He also inaugurated a war on drugs in which he swore to kill or lock up every drug dealer and user in the country. He ordered the national police to pursue suspects with a vengeance. Of the roughly 7,000 people killed in this brief but bloody war on drugs, about two-thirds were killed by unknown gunmen.

“What President Duterte calls a war on drugs, in essence, has been a war on the poor,” said Rawya Rageh, is a senior crisis adviser at Amnesty International. “This wave of extrajudicial executions targeting people suspected of using or selling drugs appears deliberate, widespread, and systematic and may amount to crimes against humanity.”

Amnesty and local human rights groups say that Duterte tolerates no dissent. He has threatened to reimpose a state of emergency, a hallmark of the Marcos dictatorship. Duterte has bullied domestic critics in the Legislature, the media, and the human rights sphere.

Nightly shootings and mass arrests have become a signature of Duterte’s war on drugs, about which he is unapologetic. Upward of 100,000 people have been taken into custody. He revels in rumors that as mayor of Mindanao he killed drug suspects himself.

Philippine voters have responded with fear and awe. Malcolm Cook, a senior fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore and expert on the Philippines, said surveys show about 80 percent support the war on drugs, but an equal number fear they will be personally victimized by it. “What makes him different is that he is such a maverick and attacking so many assumed norms of Philippine politics,” Cook said. “There is no sign that he is paying a political cost. After six months in office, his popularity ratings are very high.”

Meanwhile, Duterte’s foreign policy shifts demonstrate the impact a purposeful leader can have. For years, Southeast Asian countries, working closely with the United States, tried to check Chinese expansion in the strategic South China Sea. But Duterte made clear that he didn’t care for the ironclad military alliance with the United States and would be willing to overturn decades of regional orthodoxy to forge a new deal with Beijing over the South China Sea, one of the most dangerous flashpoints in the world.

In October, a few months after he took office and before he knew who would succeed Obama, Duterte announced his “separation from the United States” at a shock press conference in Beijing. “America has lost now,” Duterte declared, pledging to be “dependent” on China. Duterte’s sudden shift threw the regional balance into disarray. And that was before Trump was elected and promised to undo Obama’s pivot to Asia and conciliatory approach to China.

CONVENTIONAL POLITICIANS considered such abrupt moves inconceivable in democratic nations. Yes, strongmen could maneuver wildly in countries where public opinion can be suppressed or managed. But over time, governments as fundamentally different as China, the European Union, and the United States adopted a bland, nonconfrontational approach to global politics. Even when the effort to downplay conflict was superficial, it reinforced the idea that a growing global community of nations respected the same taboos.

But Duterte, like Trump, has thrived while radically reorienting long-settled policies. In the Philippines, a strategic divorce from America was unthinkable a year ago, but now it’s underway. Similarly, the White House has shifted America’s approach to Russia, and many voters don’t appear to mind.

How long can pluralism survive Duterte’s kind of rule? Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, said that the Philippine president’s most controversial moves, like his violent drug war and coarse talk, fit in with regional norms, but the most important danger comes from Duterte’s threat against democracy itself. “This is a fragile democracy,” Kurlantzick said. “We should worry.”

The Philippines, Kurlantzick said, has one of the strongest executive presidencies in the world, similar to France’s. When a member of the supreme court hinted that Duterte’s drug war could eventually face judicial review, Duterte immediately raised the prospect of martial law.

“It’s very much like Trump acting as CEO of his family business,” said Cook, the Philippines expert. “He seems to think that as president, he has power over everything.” The joke in the Philippines during the US election, Cook says, was, “If you want to see what will happen when Trump wins, just look at us!”

Donald Trump developed his own persona over a lifetime in New York, but the echoes with Duterte are uncanny. In one of his first calls to a foreign leader, Trump supposedly praised Duterte’s drug war and according to Duterte, said he looked forward to meeting Duterte and getting advice about how to deal with BS (Duterte didn’t use the abbreviation). The only readout came from the Philippines, but no one in Trump’s camp disputed the account.

Back when Rodrigo Duterte was elected president of the Philippines, his type seemed almost comic — a bit scary, but on the fringe. Today, he shows how a chauvinist can rise to power not in backwater coups or in countries like Egypt that were authoritarian to begin with, but in free elections.

For some time, the United States, too, had been concentrating power in the executive branch, to the point that even staid auditors like the Economist Intelligence Unit have downgraded their estimation of its institutional health. And that was before Trump. Especially now, the perilous state of civil liberties and Philippine institutions serve as a stark warning: Popular, elected leaders can undo democracy, with the full blessing of their constituents.

Thanassis Cambanis, a fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author of “Once Upon a Revolution: An Egyptian Story.” He is a columnist for the Globe Ideas section and blogs at thanassiscambanis.com.

Trump’s Dangerous Attack on American Values

[Published at The Century Foundation.]

Why do so many people want to live in America? Why have so many, like my parents, emigrated to the United States, and why do so many prefer it over all other destinations? It’s not just because of America’s prosperous and diverse economy, or its promise of economic mobility and equality. It’s because America’s political, cultural, and religious freedoms have meant that people’s fates are less foreordained by last name, tribe, ethnicity, or religion than they are elsewhere. While imperfect, the American system has proven remarkably open to revision and improvement, trending over its history toward more openness and equality, and less discrimination and oppression. Individuals can choose their own course, and their own identity.

America’s story as an immigrant nation is neither all rosy nor simple. Racial and ethnic tensions have simmered along with every chapter of immigration, and for all the periods of openness, there have always been tragic moments when the gates were closed, including to many Jews during the Holocaust. And in many cases, America benefited economically and culturally from the arrival of refugees or immigrants created by America’s own foreign policy misadventures. My own parents came to the United States to study; one reason they stayed was because their home, Greece, was in the violent grasp of a military dictatorship that had been put in place with U.S. support. However, America also offered some Greeks like my parents a way out, and a new home. Such stories have been part of the American fabric since the beginning.

President Donald Trump’s executive order to close America’s borders to people from seven countries arbitrarily chosen as the most dangerous sources of terrorstrikes a body blow against a fundamental American conceit: that this country is a melting pot, and that we never discriminate on the basis of religion.

The anti-immigration measure unleashed over the weekend also attacked the fundamental notion of citizenship, by initially barring even permanent residents whose green card signifies they are in the last stage of the legal path toward citizenship (Trump was forced to walk back this element of the order). And it directly singled out Muslims as targets; whatever the verbal acrobatics Trump has engaged in since, his order and statements were clear; he wants to ban all Muslim immigration from these seven countries (and perhaps more later), while making special provisions to admit Christians from those same places.

Don’t Be Fooled: It’s a Muslim Ban

Of course, this is a Muslim ban, not a counter-terrorism measure. (Rudy Giuliani, a Trump adviser, confirmed as much talking to reporters.) It’s easy enough to see, if you’re open to fact-based policymaking, that a blanket ban on foreigners or members of some ethnic groups will do nothing to protect the United States from terrorist attacks, which in most cases have been perpetrated by attackers who were citizens, entered the country legally, or were members of groups not on the hot-button fear list of the day.

In standing against this shameful executive action, we certainly can and should make a case based on self interest. An immigration ban hurts America just as surely as it hurts many families and individuals. It hurts our economy, our workforce, our research and development prospects, our universities, and our vibrant tech sector. It will make our economy less competitive, our institutions weaker, and our companies less profitable. More broadly, it hurts us many times over as stewards and beneficiaries of an international order built on norms that if unevenly enforced were once quintessentially American in principle: equality, rights for all, opportunity, and colorblindness.

But most fundamentally, this outrage from the Trump White House harms us by damaging the foundation of American rule of law and equality, which are the very reasons this country has had such success and has grown into a worldwide beacon. Despite America’s checkered record, it remains a cherished home to that majority of its population descended from immigrants, and a choice destination for those seeking a freer life. There might be better places to live, but none, including the European nations with great social safety nets, offer an open society with equivalent individual rights and freedoms.

What we’ve witnessed over the last days has defied the already low expectations that Trump set in his first bellicose week in office. Unaccountable law enforcement officials denied lawyers and even members of Congress access to immigrants detained at airports. Unapologetic White House officials gloatedthat terrorists will be thwarted by an indiscriminate, punitive measure whose short-term harm is sure to be matched by its long-term ineffectiveness. While White House officials clarified parts of the order on TV and the president fanned the flames on Twitter, foreign governments began to take countermeasures and executive branch agencies appeared to trample on the separation of powers by ignoring court orders and legislative requests. Families separated by the order, and travelers whose visas and green cards were suddenly useless, scrambled to figure out when and if they could cross America’s threshold.

Under the current scheme it is likely that Trump will try to open America’s gates only, or primarily, to non-Muslims. I hope that such an effort will fall afoul of the letter of the American Constitution just as surely as it defiles its spirit. But as a longtime observer of the American political process and a student of some of its dark history, I fear that it will take uncomfortably long to reestablish a just order. Courts move slowly and deliberately. Even if they get it right on the first try, it might take years before a Supreme Court ruling strikes down a de facto Muslim ban. And maybe Donald Trump will find legalistic detours around justice, implementing his isolationist, racist, and xenophobic plan with just enough attention to detail that it squeaks through the judicial process. As George W. Bush’s torture policy showed, much can be accomplished that is against our laws and our values.

We are a stronger nation with our immigrants, those who assimilate as well as those who struggle. We are stronger for our establishment clause which separates not just church but synagogue, mosque and all other religious belief from our state. The day we make religion part of the litmus test for American belonging is the day we turn our backs on the most American idea of all: that America can always, in theory, be home to anyone who wants it badly enough. America today is neither a Christian nor chauvinist nation; it is a nation built on a communal belief, and its success is a testament to change, inclusion and secularism, to the power of a collective national ideal that accommodates all takers.

America Doesn’t Live in a Vacuum

Trump’s excesses are possible because of the abusive bloating of executive authority and security state powers. Rights-stripping, unfortunately, is also as American as apple pie, and many of George W. Bush’s escalations of federal power, fear-mongering, and immigrant abuse after 9/11 were built on erosions of rights contained in two signal pieces of legislation by Bill Clinton that were supposed to reform immigration and the legal process in death penalty and terrorism cases. As a journalist covering federal court in Boston after 9/11, I was aghast at the cavalier lack of concern among many law-abiding Americans for the legal rights of foreigners, terror suspects, and drug criminals. I was also surprised to learn how deep and bipartisan support ran for any action couched as anti-terrorism, even if its primary target was immigrants and nonviolent criminals, as demonstrated by Clinton’s “Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act” of 1996.

Obama walked back some of the worst crimes of the Bush era, ending torture, closing black sites, and rolling back some surveillance measures, but he enjoyed the perks of unfettered executive power. Guantanamo remained open, drone strikes accelerated, and America didn’t join Canada and Europe in shouldering the burden of today’s historic refugee crisis.

Now Trump has taken the tools assembled by his predecessors and is applying them to toxic ends.

What about other countries? Will they function as extras in a one-man play called “America First”? Doubtful. They will retaliate, and America will care; even Trump, probably, will care. Soon enough the world will react, and Trump and his sycophants will notice they don’t live in a vacuum. Unfortunately, like the valiant domestic protests, it will take quite a while for the response to curtain the abuse of power. But the response will be devastating. Iraq is imposing a reciprocal ban on Americans, which while mostly symbolic could undo that oh-so-important war against ISIS, whose frontline today runs through Mosul, where American and Iraqi troops are together pushing back a real terrorist threat.

And American allies, on whom America depends for so many economic and political benefits, might take umbrage at having their citizenship suddenly downgraded. Citizens of Canada, France, or the United Kingdom are suddenly demoted in the eyes of the United States to having lesser rights because of their origins—might not, in a reasonable world, the governments of Canada, France and the U.K. retaliate to make the point that all their citizens should be treated equally?

How we act in the world matters just as surely as how we act within our own borders. A parent who abuses strangers and cheats in the workplace can’t expect the same behavior to result in an ethical and peaceful home. Trump’s anti-immigrant policies won’t make us safer from terrorist attacks, nor will they solve any other American woes, real or imagined. But we shouldn’t only make the case against isolationism and chauvinism solely on efficacy. Because even if such policies worked, we should still oppose on principle all moves to close our borders, disavow American ideals, and discriminate against religious groups. We have no interest in prevailing as an authoritarian state.

Our Better Angels

Donald Trump and his team will have to moderate their contempt for political life and dissent. Even autocrats in weaker states find they have to manage and sometimes cave to public opinion. Even outright tyrants can’t ignore street protests or the discontent of vast swathes of the public. So too, Trump, even in his first climbdown on Sunday when he relented on green card holders, will learn that public support matters in political life, all the more so in a democracy, which America today most resolutely still is.

Since 9/11, Americans have struggled to find the right balance between our security and trespass against our freedoms, all too often accepting compromises on core values in a devil’s bargain to fight terrorism. In the end, our security comes from both our readiness and our values, our laws and our fundamentally democratic melting pot ideal.

For most of my life, I have tried to explain what makes America special to skeptical relatives, friends, and interlocutors from all over the world. Donald Trump’s immigration ban makes that job all the harder. But there is an answer, and it comes from the legions of Americans who instantaneously rose to fight the unjust measure. The Bill of Rights, the traditions of American citizenship, our institutions, and constitutional rule of law together pose formidable obstacles to a would-be tyrant. American history tells us that justice can prevail, even if it takes a long time. Let’s hope that we’ve learned our lessons from the last century, and that Donald Trump’s attempt to rewrite the American compact as a nativist, racist, and isolationist screed shatters before its first draft is finished.

Why It Pays to Be the World’s Policeman—Literally

[Published in Politico Magazine.]

One of Donald Trump’s campaign applause lines held that it was time for the United States to quit serving as the world’s policeman and take care of business at home.

Isolationist chestnuts like this are standard campaign fare for a certain kind of conservative; just before he embarked on the biggest expansion of American military interventionism, George W. Bush, too, ran against the idea of “nation-building.”

Set aside for a minute the fact that even during years of unabated war following Sept. 11, 2001, America has done very little nation-building. Forget, also, that it’s questionable just how accurate the shorthand of “world policeman” is to describe America’s role in today’s international security architecture.

The essential fact is that the United States sits at the pinnacle of a world order that it played a central role in designing, and which benefits no other country so much as it does — you might have guessed — America itself.

America runs a world order that might have some collateral benefits for other countries, but is largely built around US interests: to enrich America and American business; to keep Americans safe while creating jobs and profits for America’s military-industrial complex; and to make sure that America retains, as long as possible, its position as the richest, dominant global superpower. Rather than global cop, it’s more accurate to call America the world’s majority shareholder, investing its resources in global stability less out of charity than self-interest.

What this means is that as Trump develops his foreign policy — a dealmaking approach whose ultimate outlines we can only guess at — he will eventually have to walk back his promise or confront its real costs. It’s easy to paint America as the rich uncle whom the world takes advantage of. That caricature certainly resonates with Trump’s voting base. But if Trump really tries to deliver on his promise and walk away from the world, the biggest price is likely to be borne by America itself.

***

The United States and its allies, in the wake of World War II, built a web of institutions that had an ideological goal: to reduce the risk of another murderous global conflagration. The United Nations would serve as a political-diplomatic talk shop that would reduce the chance of accidental superpower war and create avenues for managing the conflicts that did break out. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were designed to minimize the risk of another Great Depression. An acronym soup of other institutions sprang up along the same lines. When memories of fascism were fresh and Washington feared the allure of communism, it made some far-sighted, pragmatic moves. It funded the Marshall Plan for Europe, paying so the continent could recover economically and emerge to become a pivotal U.S. ally–and a profitable market for US companies. U.S. military occupiers in Japan and South Korea decreed progressive reforms and land redistributions in order to outflank communists.

In some cases, America really has underwritten most of the funding for international institutions, whether their purpose is to monitor ancient ruins (UNESCO) or inspect nuclear sites (IAEA). It hasn’t done so out of altruism. The investment has paid itself back many times over. These institutions have worked imperfectly, but they build goodwill and reduce risk. That’s good for the world in general, but it’s great for America.

It’s true that America’s role is expensive. In 2015, America spent more than the next seven nations combined on defense. Worried about this gap in the years after 9/11, some American officials and neoconservative ideologues complained that “Old Europe” should pay more for its defense. Like Trump, they argued that Europe has been able to reap an economic windfall because America shoulders so much of the NATO security umbrella.

At best, this analysis is a dangerous exaggeration; Europe could and probably should shoulder more of the cost, but the US investment in NATO is worthwhile for its own sake. At worst, by threatening NATO, the “free-rider” trope sets up America to shoot itself in the foot – shaking its security and breaking up a system with huge direct benefits to Americans.

Rather than a nation rooked by crafty foreigners, it makes more sense to see America at the center of a web of productive investments. Here’s how it works:

First, most of America’s defense spending functions as a massive, job creating subsidy for the U.S. defense industry. According to a Deloitte study, the aerospace and defense sector directly employed 1.2 million workers in 2014, and another 3.2 million indirectly. Obama’s 2017 budget calls for $619 billion in defense spending, which is a direct giveback to the American economy, and only $50 billion in foreign aid – and even that often ends up in American pockets through grants that benefit American farmers, aid organizations, and other US interest groups. The U.S. military, and the Veterans Administration, are an almost socialist paradise of equality, job security and full health care when compared to life for Americans not on the payroll of the Defense Department and its generously (even absurdly) remunerated contractors. The defense budget, by playing on America’s obsession with security rather than social welfare, allows Washington to pump a massive stimulus into the economy every year without triggering another Tea Party.

Second, America’s steering role in numerous regions — NATO, Latin America, and the Arabian peninsula — gives it leverage to call the shots on matters of great important to American security and the bottom line. For all the friction with Saudi Arabia, for instance, the Gulf monarchy has propped up the American economy with massive Treasury bill purchases, and by adjusting oil production at America’s request to cushion the effect of policy priorities like the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Third, and most importantly, if you listen the biggest critics of the new world order, what you’ll hear is that it’s rigged – in America’s favor. America’s “global cop” role means that shipping lanes, free trade agreements, oil exploration deals, ad hoc military coalitions, and so on are maintained to the benefit of the U.S. government or U.S. corporations. The truth is that America puts its thumb on the scale to tilt the world’s not-entirely free markets to America’s benefit. Nobody would be more thrilled for America to pull back than its economic rivals, like China.

Perhaps that’s why analysts in the business of predicting world affairs don’t think Trump is going to abandon America’s “world policeman” portfolio once he looks at the bottom line.

“Trump wants to be seen as projecting strength around the world and intends to expand spending on U.S. defense,” wrote Eurasia group’s Ian Bremmer shortly after the election. He might be more abrasive, and he might pressure some of America’s bottom-tier allies. But if he wants to be a strongman, he’ll have to keep America’s stick.

Obama, too, apparently thinks Trump will like being the world’s policeman even more than he’ll like being Putin’s friend. “There is no weakening of resolve when it comes to America’s commitment to maintaining a strong and robust NATO relationship and a recognition that those alliances aren’t just good for Europe, they’re good for the United States. And they’re vital for the world,” outgoing President Obama said on his valedictory trip to Europe, claiming confidence that Trump shared that view of global alliances.

Within Trumpworld, there’s no question a real rift exists on this question. Isolationist-nationalist America-firsters, like Steve Bannon, really do want to see America pull back, and downplay the costs in the interests of their ideological goals. Profit-driven internationalists like Rex Tillerson, however, are intimately acquainted with the benefits of keeping an American hand in global affairs.

Trump might like the sound of handing in America’s resignation as global cop. His voters might like it even more. But if pulling back makes America poorer and more vulnerable, the costs will land squarely on Trump.

When it comes time to choose between the two camps, Trump might find himself torn between an isolationist camp he connects with emotionally and an internationalist one that will — in the gross calculus of profits and power — be more of a winner. That’s a feeble rationale for a sound international order, but it might be the best one going in the age of Trump.

Moscow Is Ready to Rumble

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

It should come as no surprise that many Russians will mourn this month, a quarter century after Mikhail Gorbachev resigned as president of the Soviet Union and overnight, one of the great world empires simply dissolved.

Today a tense realignment is underway, as a resurgent Russia jostles to the table and upends American nostrums about the post-Cold War order. Russia has given the United States plenty of grist for worry with its apparent meddling in the US presidential election. President Vladimir Putin’s hackers and propagandists appear ready and willing to work to tip the balance to the right in upcoming European elections as well.

While these Russian endeavors are important, they’re a sideshow to the main event: a long geopolitical struggle in which the United States briefly gained a dominant position, but which today is more evenly matched.

In many respects, Russia’s position has been consistent so long as Putin has been in power. When it comes to terrorists, separatists, or defiant neighbors, force matters more than moral jockeying. Recent events confirm Russia’s view of itself. Aleppo’s rebels collapsed before a Russian-led onslaught. Turkey is desperate to remain in Russia’s good graces; the theatrical assassination of Russia’s ambassador to Turkey in an art gallery Monday only brings the two countries into closer cooperation.

Incoming President Donald Trump, meanwhile, appears willing to grant Russia the official recognition that Putin has always craved.

Trump and Putin — two macho leaders with empire-sized egos — tempt analysts to reduce the US-Russia relationship to personalities. But the unfolding clash stems from essentials. Russia has considerable hard power, starting with its nuclear arsenal and enormous territory. Its interests conflict with those of the United States and frequently of Europe, through tsarist and Soviet times down to the present. And finally, Moscow’s acerbic rhetoric and commitment to sovereignty and consistency place it in constant opposition in international forums to the United States, with its moralistic style and constant talk of human rights and democracy.

“Putin is about restoring his country as a major power recognized by the world,” said Dmitri V. Trenin, a former officer in the Soviet and Russian armies who now heads the Carnegie Moscow Center, an international think tank.

No amount of affection between Trump and Putin will change the fact that Russia’s interests never really overlapped with America’s. “The best we can hope for is to turn confrontation into competition,” Trenin said.

Trump won’t be the first recent US leader to woo Moscow. Every president since George H. W. Bush has tried to cultivate harmonious ties. Clinton might have helped Boris Yeltsin win a second term. George W. Bush famously waxed rhapsodic about Putin’s eyes. Barack Obama tried to reset. Trump will come into office on a wave of gushing rhetoric.

(Of course, all bets are off if some of the more unlikely theories turn out to be true and Trump turns out to be a sort of Manchurian Candidate with preexisting ties to Putin and a secret plan to realign the United States with Russia. But unless and until evidence emerges, we’ll have to chart the future based on what we’ve heard and observed so far.)

Through all these zigs and zags, Russia has consistently reasserted its alpha position in the former Soviet space while consolidating authoritarian state power in its heartland. Its techniques and rhetoric — against Chechen separatists, Russian oligarchs, political dissenters, suspected terrorists — won’t play by rules it considers rigged in favor of the West.

For Trump, this fundamental divergence means that despite any honeymoon period, the conversations are going to be difficult and full of disagreement.

Trump might see eye to eye with Putin when it comes to the Russian president’s reflex to crush dissent, and he may accept Russia’s annexation of Crimea. But Russian expansion will clash with America’s sphere of interests, and new boundaries will have to be negotiated.

Russia wants full hegemony in its old sphere of influence, which means a NATO rollback, and it wants a transactional international order stripped of even the rhetoric of international humanitarian law and its moral accoutrements.

Meanwhile, the United States will continue to preach a prosperity gospel built on capitalism, democracy, and lower-case liberalism.

Putin wants to erase once and for all the image of Russia as the tottering, ex-empire low on cash, trying to bully the world with a limping army whose rusty equipment is staffed by alcoholics with truncated life spans.

A multipolar world is full of fuzzy boundaries that breed conflict and uncertainty. The United States might be in first place, but China is gaining, and neither can patronizingly dismiss Russia as a “regional power.” The European Union is politically fragmented and economically hobbled, but it remains one of the richest markets in the world and, like Russia, possesses geostrategic depth. The fallacy of the American interregnum after 1991 was that old standards of geopolitical power no longer applied. Now the world has been put back on notice that they do, but that doesn’t answer the specific question: What should the United States do about Russia?

The first step toward a more effective Russia policy is to understand Moscow’s grievances. The sudden collapse of an empire of global scope traumatized many former Soviet citizens.

After Gorbachev’s Christmas-day resignation, Boris Yeltsin led an independent Russia into what was supposed to be a bright new age of capitalist democracy. Expert American advisers helped usher in a headlong rush to privatize state-owned industries. Whatever their intention, the chaotic process amounted to a looting of some of the former Soviet Union’s prized assets by a tiny circle of corrupt oligarchs. Yeltsin’s inner circle engaged in epic corruption. Some of the experts argued that a flawed sell-off of Communist-era industries was a necessary shock to shed Soviet mores. The result was catastrophic. Citizens lost the social safety net, while gaining very little in return. The visible results of capitalism piled up only for a tiny elite.

Added to the quotidian discomfort was a wrenching loss of national status. An ailing Yeltsin lurked out of view, while oligarchs ran riot and former Soviet republics made a mockery of Russia’s former primacy. NATO spread closer to Russia’s borders.

“Russia’s brief experience of democratic life was an experience of being pushed around by the United States,” said Mark MacKinnon, a Canadian journalist and author of “The New Cold War.”

Yeltsin’s Communist challenger was expected to win in 1996, but a unified front of oligarchs, worried they might lose their privileges, and campaign experts dispatched by Clinton, saved the day for Yeltsin, if not for his constituents. The episode was memorialized in the 2003 American comedy “Spinning Boris.”

“Many Russians look at what’s happening now in the United States and giggle that it’s payback time,” MacKinnon said.

Russian influence reached its nadir when NATO intervened in Bosnia and Kosovo, which Russia considered parts of its sphere of influence. Putin took power the year after the Kosovo campaign, and doggedly began rebuilding Russia’s military and intelligence prowess. His scorched-earth tactics in Chechnya presaged his approach to Syria.

By 2008, Putin felt confident and invaded Georgia, on the pretext of defending the ethnic Russian minority there. The act of aggression provoked apoplectic rhetoric but little else.

Meanwhile, analysts say, Putin was frustrated that America didn’t show more gratitude that Russia had not opposed the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and campaign in Libya in 2011.

Ever since, he has sought opportunities to exploit Western disarray, as he did with the 2014 invasion of Ukraine and annexation of the Crimea, and the 2015 intervention in Syria.

Russian diplomats have crowed about American fecklessness in Syria and were visibly buoyed when over the Pentagon’s objections the US State Department negotiated an agreement in September — which never was implemented — to cooperate with Russian forces against terrorists in Syria.

The path forward is risky. A belligerent Russia can cause a great deal of destruction and spread instability. Russia threatened Europe’s natural gas supply. It lied about its military activities in Crimea. Its muscle-flexing has rattled Europe and NATO. Turkey challenged Russia, shooting down a fighter plane, and quickly lost the ensuing face-off. Russia played hardball, putting tourism and economic relations on ice until Turkey apologized and scaled back its ambitions in Syria where those ambitions clashed with Russia’s. Russia won that round, and other countries noticed.

Some analysts, like Nikolay Kozhanov, an expert at the British think tank Chatham House, have argued that Putin’s most disruptive moves came largely as the result of Western mistakes. As a result, Western unity could severely limit Russian capacity.

Sooner or later, Russia experts agree that Putin will test Trump. Clashes could come in Poland, or the Baltics, where Trump has suggested NATO is overextended. Tensions could flare in places where Russia already chafes at the proximity of NATO forces, such as around the Arctic and the North and Baltic seas.

“Trump will identify his red lines, because Putin is going to test them,” MacKinnon said. “The feeling in Moscow will be, how can we take advantage of this period, now that there’s a leader in Washington willing to let Russia get away with things it couldn’t have otherwise.”

On a November visit to Moscow, he said many of his Russian contacts expressed surprise that Trump had won the election. Initial concern that Trump could be a loose cannon turned to glee when he announced a series of Cabinet picks viewed sympathetically by the Kremlin.

Derek Chollet, who dealt with the Russians as an official on Obama’s National Security Council, said that Russia will take advantage of the new administration. Putin, he predicted, will do all he can to undermine NATO and the EU, influence energy markets, and drive a wedge between the United States and Europe.

“Judging on his rhetoric so far, Trump will be the most pro-Russian president since World War II,” Chollet said. “He likes the art of the deal, but to what end?”

We’ll find out where the United States will check Putin’s expansionism when we learn Trump’s priorities, whether they have to do with security alliances, business partnerships, or something else.

The first seminal crisis will come when Putin challenges an interest dear to the Trump administration. Perhaps the Russian government will confiscate the assets of an American corporation or clash with NATO forces or invade the Baltic republics or enter a showdown with Europe.

Trump will presumably have the advantage, from America’s unparalleled military and the imposing NATO infrastructure, to an economy orders of magnitude richer and more productive than Russia’s. But if America has squandered international goodwill and allowed alliances to fray, those assets will prove as ineffectual as they have in the most recent contests in which Putin has outfoxed the West.

The chapter in contemporary history in which America stood alone at the top has come to a close. Russia will return to the top tier, along with the United States, China, and potentially other alliances. But the natural size of its power, whether measured in wealth, military power, or global political influence, is not as great as Putin appears to think it is. Trump might be willing to accept a bigger Russian role than his predecessors, but he’s unlikely to forfeit first place.