A plan to rebuild Syria no matter who wins war

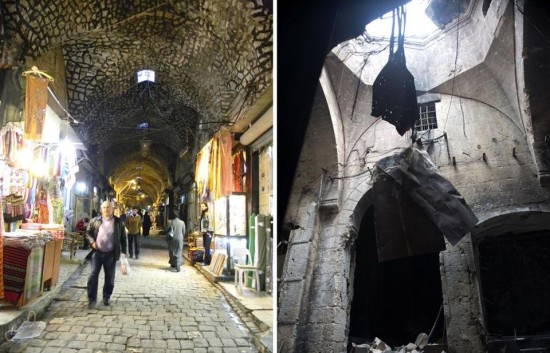

The souk in Aleppo, before and after its destruction in 2012. LEFT: WIKICOMMONS; RIGHT: MIGUEL MEDINA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT—The first year of Syria’s uprising, 2011, largely spared Aleppo, the country’s economic engine, largest city, and home of its most prized heritage sites. Fighting engulfed Aleppo in 2012 and has never let up since, making the city a symbol of the civil war’s grinding destruction. Rebels captured the eastern side of the city while the government held the west. The regime dropped conventional munitions and then barrel bombs on the rebels, who fought back with rockets and mortars. In 2012, the historical Ottoman covered souk was destroyed. In 2013, shelling destroyed the storied minaret of the 11th-century Ummayid Mosque. Apartment blocks were reduced to rubble. More than 3 million residents fled, out of a prewar population of 5 million. Today, residents say the city is virtually uninhabitable; most who remain have nowhere else to go.

In terms of sheer devastation, Syria today is worse off than Germany at the end of World War II. Bashar Assad’s regime and the original nationalist opposition are locked in combat with each other and also with a third axis, the powerful jihadist current led by the Islamic State. And yet, even as the fighting continues, a movement is brewing among planners, activists and bureaucrats—some still in Aleppo, others in Damascus, Turkey, and Lebanon—to prepare, right now, for the reconstruction effort that will come whenever peace finally arrives.

In downtown Beirut, a day’s drive from the worst of the war zone, a team of Syrians is undertaking an experiment without precedent. In a glass tower belonging to the United Nations’ Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, a project called the National Agenda for the Future of Syria has brought together teams of engineers, architects, water experts, conservationists, and development experts to grapple with seemingly impossible technical problems. How many years will it take to remove the unexploded bombs and rubble and then restore basic water, sewerage, and power? How many tons of cement and liters of water will be needed to replace destroyed infrastructure? How many cranes? Where could the 3 million displaced Aleppans be temporarily housed during the years or decades it might take to restore their city? And beneath all these technical questions they face a deeper one, as old as urban warfare itself: How do you bring a destroyed city back to life?

Critics dismiss the ongoing planning effort as a premature boondoggle, keeping technocrats busy creating blueprints that will have to be revised when fighting finally ebbs. But Thierry Grandin, a consultant for the World Monuments Fund who has worked and lived in Aleppo since the 1980s and is currently involved in reconstruction planning, disagrees. “It is good to do the planning now, because on day one we will be ready,” Grandin says. “It might come in a year, it might come in 20, but eventually there will be a day one. Our job is to prepare.”

The team planning the country’s future is a diverse one. Some are employed by the government of Syria, others by the rebels’ rival provisional government. Still others work for the UN, private construction companies, or nongovernmental organizations involved in conservation, like the World Monuments Fund. The Future of Syria project aims to serve as a clearinghouse, and to create a master menu of postwar planning options. As the group’s members outline a path toward renewal, they’re considering everything from corruption and constitutional reform to power grids, antiquities, and health care systems.

The task they have before them beggars comprehension. Across Syria, more than one-third of the population is displaced. Aleppo is in tatters, its center completely destroyed. The population exodus has claimed most of the city’s craftsmen, medical personnel, academics, and industrialists.

A modern country has been unmade during four years of conflict, and nowhere is the toll more apparent than in once-alluring Aleppo. But after horrifying conflict, countless places have found a way to return to functionality. What’s new in Syria is the attempt to come up with a neutral plan while the conflict is still in train. And Aleppo, the country’s historic urban jewel, will be the central test.

TO FIND A SIMILAR example of planning during wartime before the outcome was known, you have to go back to World War II. Allied forces spent years preparing for the physical, economic, and political reconstruction of Germany and Japan even before they could be sure who would win. Today, Americans tend mostly to recall the symbolic reconstruction after the war: the Nuremberg trials and the Marshall Plan, a colossal foreign aid program.

But undergirding those triumphs was the vast logistical operation of erecting new cities. It took decades to clear the moonscapes of rubble and to rebuild, in famous targets like Dresden and Hiroshima but in countless other places as well, from Coventry to Nanking. Some places never recovered their vitality.

Since then, a litany of divided and devastated cities has been left by other conflicts. Even those that eventually regained a sense of normalcy, like Beirut, Sarajevo, or Grozny, generally survived rather than thrived. Only a few countries—East Timor, Angola, Rwanda—offer what Syrian planners call “glimmers of hope,” as places that suffered terrible man-made disasters and then bounced back.

Of course, Syrian planners cannot help but pay attention to the model closest to home: Beirut, a city almost synonymous with civil war and flawed reconstruction. The planners and technocrats in the UN ESCWA tower overlook a gleamingly restored but vacant downtown from behind a veritable moat of blast barriers and sealed roads. Shell-pocked abandoned buildings stand as evidence of the tangled ownership disputes that have held back reconstruction a full quarter-century after the Lebanese civil war.

“We don’t want to end up like Beirut,” one of the Syrian planners says, referring to the physical problems but also to a postwar process in which militia leaders turned to corrupt reconstruction ventures as a new source of funds and power. He spoke anonymously; the Future of Syria team, which is led by a former Syrian deputy prime minister named Abdallah Al Dardari, doesn’t give on-the-record briefings. Since their top priority is to maintain buy-in from Syrians on all sides, they try to avoid naming names so as not to dissuade people they hope will use their plans when the war ends.

Syria’s national recovery will depend in large part on whether its industrial powerhouse Aleppo can bounce back. Until 2011, Aleppo had been celebrated for millenniums for its beauty and commerce. The citadel overlooking the center is a world heritage site. The old city and its covered market were vibrant, functioning exemplars of Islamic and Ottoman architecture, surrounded by the wide leafy avenues of the modern city. Aleppan traders plied their wares in Turkey, Iraq, the Levant, and all the way south to the Arabian peninsula. The city’s workshops, famed above all for their fine textiles, export millions of dollars’ worth of goods every week even now, and the economy has expanded to include modern industry as well.

Today, however, the city’s water and power supply are under the control of the Islamic State. Entire neighborhoods have collapsed under regime bombing and shelling: government buildings, hospitals, landmark hotels, schools, prisons. Aleppo is split between a regime side with vestiges of basic services, and a mostly depopulated rebel-controlled zone, into which the Islamic State and the Al Qaeda-affiliated Nusra Front have made inroads over the last year. A river of rubble marks the no-man’s land separating the two sides. The only way to cross is to leave the city, follow a wide arc, and reenter from the far side.

For now, said an architect who works for the rebel government in Aleppo under the pseudonym Tamer el Halaby, today’s business is simply survival, like digging 20 makeshift wells that fulfill minimal water needs. (He prefers not to have his real name published for fear that the government might target relatives on the other side of Aleppo.) Parts of the old city won’t be inhabitable for years, he told me by Skype, because the ground has literally shifted as a result of bombing and shelling.

“It will take a long time and cost a lot of money for this city to work again,” he said.

CLOSE TO A THOUSAND Syrians have consulted on the Future of Syria project, which comprises at least two ambitious initiatives rolled into one. The first and more obvious is creating realistic options to fix the country after the war—in some cases literal plans for building infrastructure systems and positioning construction equipment, in other cases guidelines for shaping governance.

At the Future of Syria, hospital administrators, civil engineers, and traffic coordinators each work on their given fields. They’re familiar with global “best practices,” but also with how things work in Syria, so they’re not going to propose pie-in-the-sky ideas. These planners also understand that who wins the construction contracts will depend on who wins the war. If some version of the current regime remains in charge, it will probably direct massive contracts toward patrons in Russia, China, or Iran. The opposition, by contrast, would lean toward firms from the West, Turkey, and the Gulf.

“Who will have the influence in Syria after the conflict? That will dictate who is involved in redevelopment. It all depends on who ends up being in political control,” says Richard J. Cook, a longtime UN official who supervised postconflict construction in Palestinian refugee camps and now works for one of the Middle East’s largest construction conglomerates, Dar Al-Handasah Consultants (Shair and Partners). Along with other companies, Dar Al-Handasah has offered its lessons learned from Lebanon’s reconstruction process to Syrian planners, and plans to compete to work in postwar Syria.

That leads to the second, more subtle, innovation of the Future of Syria project. For its plans to matter, they need to be politically viable no matter who is governing. So the planners have worked hard to persuade experts from all factions to contribute to the 57 different sectoral studies, hoping to come up with feasible rebuilding options that would be considered by a future Syrian authority of any stripe. Today, nearly 200 experts work full time for the project.

At the current level of destruction, the project planners estimate the reconstruction will cost at least $100 billion. Regardless of how it’s financed—loans, foreign aid, bonds—that’s a financial bonanza for whoever controls the reconstruction process. Some would-be peacemakers have suggested that reconstruction plans could even be used as enticements. If opposition militants and regime constituents think they’ll make more money rebuilding than fighting, they might have a Machiavellian incentive to make peace.

Underlying the details—mapping destroyed blocks, surveying the condition of the citadel, studying sewers—are bigger philosophical questions. How can a destroyed city be rebuilt, when the combination of people, economy, and buildings can never be reconstituted? Can you use reconstruction to undo the human damage of sectarianism and conflict? Recently a panel of architects and heritage experts from Sweden, Bosnia, Syria, and Lebanon convened in Beirut to discuss lessons for Syria’s reconstruction—one of the many distinct initiatives parallel to the Future of Syria project.

“You should never rebuild the way it was,” said Arna Mackic, an architect from Mostar. That Bosnian city was divided during the 1990s civil war into Muslim and Catholic sides, destroying the city center and the famous Stari Most bridge over the Neretva River. “The war changes us. You should show that in rebuilding.”

In the case of Mostar, the UN agency UNESCO reconstructed the bridge and built a restored central zone where Muslims and Catholics were supposed to create a harmonious new postwar culture. Instead, Mackik says, the sectarian communities keep to their own enclaves. Bereft of any common symbols, the city took a poll to figure out what kind of statue to erect in the city center. All the local figures were too polarizing. In the end they settled on a gold-colored statue of the martial arts star Bruce Lee.

“It belongs to no one,” Mackic says. “What does Bruce Lee mean to me?”

Despite such pitfalls, one area of potential for the planning process—and eventually for the reconstruction of Aleppo—is that it could offer the city’s people a form of participatory democracy that has so far eluded the Syrian regime and sadly, the opposition as well. People consulted about the shape of their reconstituted neighborhoods or roads will have been offered a slice of citizenship alien to most top-down Syrian leadership.

“You are being democratic without the consequences of all the hullabaloo of formal democratization,” says one of the Syrian planners who has contributed to the Future of Syria project and spoke on condition of anonymity.

What is certain is that putting Syria back together again is likely to be as least as expensive as imploding it. A great deal of money has been invested in Syria’s destruction— by the regime, the local parties to the conflict, and many foreign powers. A great deal of money will be made in the aftermath, in a reconstruction project that stands to dwarf anything seen since after World War II.

How that recovery is designed will help determine whether Syria returns to business as usual, sowing the seeds for a reprise of the same conflict—or whether reconstruction allows the kind of lasting change that the resolution of war itself might not.