Moscow Is Ready to Rumble

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

It should come as no surprise that many Russians will mourn this month, a quarter century after Mikhail Gorbachev resigned as president of the Soviet Union and overnight, one of the great world empires simply dissolved.

Today a tense realignment is underway, as a resurgent Russia jostles to the table and upends American nostrums about the post-Cold War order. Russia has given the United States plenty of grist for worry with its apparent meddling in the US presidential election. President Vladimir Putin’s hackers and propagandists appear ready and willing to work to tip the balance to the right in upcoming European elections as well.

While these Russian endeavors are important, they’re a sideshow to the main event: a long geopolitical struggle in which the United States briefly gained a dominant position, but which today is more evenly matched.

In many respects, Russia’s position has been consistent so long as Putin has been in power. When it comes to terrorists, separatists, or defiant neighbors, force matters more than moral jockeying. Recent events confirm Russia’s view of itself. Aleppo’s rebels collapsed before a Russian-led onslaught. Turkey is desperate to remain in Russia’s good graces; the theatrical assassination of Russia’s ambassador to Turkey in an art gallery Monday only brings the two countries into closer cooperation.

Incoming President Donald Trump, meanwhile, appears willing to grant Russia the official recognition that Putin has always craved.

Trump and Putin — two macho leaders with empire-sized egos — tempt analysts to reduce the US-Russia relationship to personalities. But the unfolding clash stems from essentials. Russia has considerable hard power, starting with its nuclear arsenal and enormous territory. Its interests conflict with those of the United States and frequently of Europe, through tsarist and Soviet times down to the present. And finally, Moscow’s acerbic rhetoric and commitment to sovereignty and consistency place it in constant opposition in international forums to the United States, with its moralistic style and constant talk of human rights and democracy.

“Putin is about restoring his country as a major power recognized by the world,” said Dmitri V. Trenin, a former officer in the Soviet and Russian armies who now heads the Carnegie Moscow Center, an international think tank.

No amount of affection between Trump and Putin will change the fact that Russia’s interests never really overlapped with America’s. “The best we can hope for is to turn confrontation into competition,” Trenin said.

Trump won’t be the first recent US leader to woo Moscow. Every president since George H. W. Bush has tried to cultivate harmonious ties. Clinton might have helped Boris Yeltsin win a second term. George W. Bush famously waxed rhapsodic about Putin’s eyes. Barack Obama tried to reset. Trump will come into office on a wave of gushing rhetoric.

(Of course, all bets are off if some of the more unlikely theories turn out to be true and Trump turns out to be a sort of Manchurian Candidate with preexisting ties to Putin and a secret plan to realign the United States with Russia. But unless and until evidence emerges, we’ll have to chart the future based on what we’ve heard and observed so far.)

Through all these zigs and zags, Russia has consistently reasserted its alpha position in the former Soviet space while consolidating authoritarian state power in its heartland. Its techniques and rhetoric — against Chechen separatists, Russian oligarchs, political dissenters, suspected terrorists — won’t play by rules it considers rigged in favor of the West.

For Trump, this fundamental divergence means that despite any honeymoon period, the conversations are going to be difficult and full of disagreement.

Trump might see eye to eye with Putin when it comes to the Russian president’s reflex to crush dissent, and he may accept Russia’s annexation of Crimea. But Russian expansion will clash with America’s sphere of interests, and new boundaries will have to be negotiated.

Russia wants full hegemony in its old sphere of influence, which means a NATO rollback, and it wants a transactional international order stripped of even the rhetoric of international humanitarian law and its moral accoutrements.

Meanwhile, the United States will continue to preach a prosperity gospel built on capitalism, democracy, and lower-case liberalism.

Putin wants to erase once and for all the image of Russia as the tottering, ex-empire low on cash, trying to bully the world with a limping army whose rusty equipment is staffed by alcoholics with truncated life spans.

A multipolar world is full of fuzzy boundaries that breed conflict and uncertainty. The United States might be in first place, but China is gaining, and neither can patronizingly dismiss Russia as a “regional power.” The European Union is politically fragmented and economically hobbled, but it remains one of the richest markets in the world and, like Russia, possesses geostrategic depth. The fallacy of the American interregnum after 1991 was that old standards of geopolitical power no longer applied. Now the world has been put back on notice that they do, but that doesn’t answer the specific question: What should the United States do about Russia?

The first step toward a more effective Russia policy is to understand Moscow’s grievances. The sudden collapse of an empire of global scope traumatized many former Soviet citizens.

After Gorbachev’s Christmas-day resignation, Boris Yeltsin led an independent Russia into what was supposed to be a bright new age of capitalist democracy. Expert American advisers helped usher in a headlong rush to privatize state-owned industries. Whatever their intention, the chaotic process amounted to a looting of some of the former Soviet Union’s prized assets by a tiny circle of corrupt oligarchs. Yeltsin’s inner circle engaged in epic corruption. Some of the experts argued that a flawed sell-off of Communist-era industries was a necessary shock to shed Soviet mores. The result was catastrophic. Citizens lost the social safety net, while gaining very little in return. The visible results of capitalism piled up only for a tiny elite.

Added to the quotidian discomfort was a wrenching loss of national status. An ailing Yeltsin lurked out of view, while oligarchs ran riot and former Soviet republics made a mockery of Russia’s former primacy. NATO spread closer to Russia’s borders.

“Russia’s brief experience of democratic life was an experience of being pushed around by the United States,” said Mark MacKinnon, a Canadian journalist and author of “The New Cold War.”

Yeltsin’s Communist challenger was expected to win in 1996, but a unified front of oligarchs, worried they might lose their privileges, and campaign experts dispatched by Clinton, saved the day for Yeltsin, if not for his constituents. The episode was memorialized in the 2003 American comedy “Spinning Boris.”

“Many Russians look at what’s happening now in the United States and giggle that it’s payback time,” MacKinnon said.

Russian influence reached its nadir when NATO intervened in Bosnia and Kosovo, which Russia considered parts of its sphere of influence. Putin took power the year after the Kosovo campaign, and doggedly began rebuilding Russia’s military and intelligence prowess. His scorched-earth tactics in Chechnya presaged his approach to Syria.

By 2008, Putin felt confident and invaded Georgia, on the pretext of defending the ethnic Russian minority there. The act of aggression provoked apoplectic rhetoric but little else.

Meanwhile, analysts say, Putin was frustrated that America didn’t show more gratitude that Russia had not opposed the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and campaign in Libya in 2011.

Ever since, he has sought opportunities to exploit Western disarray, as he did with the 2014 invasion of Ukraine and annexation of the Crimea, and the 2015 intervention in Syria.

Russian diplomats have crowed about American fecklessness in Syria and were visibly buoyed when over the Pentagon’s objections the US State Department negotiated an agreement in September — which never was implemented — to cooperate with Russian forces against terrorists in Syria.

The path forward is risky. A belligerent Russia can cause a great deal of destruction and spread instability. Russia threatened Europe’s natural gas supply. It lied about its military activities in Crimea. Its muscle-flexing has rattled Europe and NATO. Turkey challenged Russia, shooting down a fighter plane, and quickly lost the ensuing face-off. Russia played hardball, putting tourism and economic relations on ice until Turkey apologized and scaled back its ambitions in Syria where those ambitions clashed with Russia’s. Russia won that round, and other countries noticed.

Some analysts, like Nikolay Kozhanov, an expert at the British think tank Chatham House, have argued that Putin’s most disruptive moves came largely as the result of Western mistakes. As a result, Western unity could severely limit Russian capacity.

Sooner or later, Russia experts agree that Putin will test Trump. Clashes could come in Poland, or the Baltics, where Trump has suggested NATO is overextended. Tensions could flare in places where Russia already chafes at the proximity of NATO forces, such as around the Arctic and the North and Baltic seas.

“Trump will identify his red lines, because Putin is going to test them,” MacKinnon said. “The feeling in Moscow will be, how can we take advantage of this period, now that there’s a leader in Washington willing to let Russia get away with things it couldn’t have otherwise.”

On a November visit to Moscow, he said many of his Russian contacts expressed surprise that Trump had won the election. Initial concern that Trump could be a loose cannon turned to glee when he announced a series of Cabinet picks viewed sympathetically by the Kremlin.

Derek Chollet, who dealt with the Russians as an official on Obama’s National Security Council, said that Russia will take advantage of the new administration. Putin, he predicted, will do all he can to undermine NATO and the EU, influence energy markets, and drive a wedge between the United States and Europe.

“Judging on his rhetoric so far, Trump will be the most pro-Russian president since World War II,” Chollet said. “He likes the art of the deal, but to what end?”

We’ll find out where the United States will check Putin’s expansionism when we learn Trump’s priorities, whether they have to do with security alliances, business partnerships, or something else.

The first seminal crisis will come when Putin challenges an interest dear to the Trump administration. Perhaps the Russian government will confiscate the assets of an American corporation or clash with NATO forces or invade the Baltic republics or enter a showdown with Europe.

Trump will presumably have the advantage, from America’s unparalleled military and the imposing NATO infrastructure, to an economy orders of magnitude richer and more productive than Russia’s. But if America has squandered international goodwill and allowed alliances to fray, those assets will prove as ineffectual as they have in the most recent contests in which Putin has outfoxed the West.

The chapter in contemporary history in which America stood alone at the top has come to a close. Russia will return to the top tier, along with the United States, China, and potentially other alliances. But the natural size of its power, whether measured in wealth, military power, or global political influence, is not as great as Putin appears to think it is. Trump might be willing to accept a bigger Russian role than his predecessors, but he’s unlikely to forfeit first place.

October surprise? No, beware the November blitz

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

AMERICAN ELECTION OBSERVERS often talk about the October surprise, the last-minute revelation that can shift the outcome. In international affairs, there’s a potentially more dangerous phenomenon: the November blitz.

When American presidential elections produce a transition — a sure thing when the incumbent isn’t running, like this year — the 10 weeks between Election Day and the inauguration can produce a jumble of last-minute power grabs and other maneuvers by governments overseas.

Sensing danger ahead under a new president, or gambling that America will be busy with its leadership transition, foreign powers often make bold, risky, or destabilizing moves during the lame-duck period of an outgoing president. Sometimes the architects think they’ll never get a better deal. In other cases, they expect to irritate the United States but figure they’ll escape with minimal backlash from a president on the way out.

The most recent example came in 2008 after Barack Obama’s election, when Israel unleashed a war in Gaza. The operation prompted international opprobrium for the widespread strikes against civilian targets. Israel launched the war on Dec. 28, 2008, and ended it just two days before Obama’s inauguration on Jan. 20, 2009. Officials gambled that George W. Bush, the pro-Israel president they knew, would be angry but not enough to withhold weapons deliveries or otherwise punish Israel — and they were right. It was a classic November blitz, even though it took place in December and January.

Reaching further back to the closing months of 2000, President Bill Clinton pulled every string he could conjure to force Israeli and Palestinian negotiators to reach a historic peace deal. With just days left in his presidency the effort unraveled.

Today, the world feels even more unsettled than it did eight years ago. Predictability is the grease that keeps the international system humming, and it’s in short supply. Nowadays figures such as Vladimir Putin — not to mention the GOP presidential nominee, Donald Trump — have injected unprecedented unpredictability into international rhetoric. Oil prices and financial markets haven’t behaved consistently, and hot wars in Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, and Libya have to some degree drawn in almost every major military power in the world. Far-right movements in Europe and the United States have opened up new, dark possibilities: The age of open borders could be drawing to a close, while the supposedly stabilizing umbrella of international agreements and institutions is being strained more than at any point since the end of World War II.

That volatile mix opens the door to gambles. What kind of lame-duck period meltdowns and provocations can the United States expect after Nov. 8, and can it do anything to minimize the risk?

THE TOP FOREIGN contender for machinations in the lame-duck period is the same culprit already blamed for an October surprise: Russia. Just as Putin’s security state is alleged to be behind hacking and other shady moves to help Trump, Russia’s preferred candidate, win the US election, it is highly likely to move in the interregnum to shore up its position.

“Americans voting for a president on Nov. 8 must realize that they are voting for peace on planet Earth if they vote for Trump,” Russian politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky said, according to Reuters. “But if they vote for Hillary, it’s war. It will be a short movie. There will be Hiroshimas and Nagasakis everywhere.”

Zhirinovsky is a bombastic bit player in Russia, but his aggressive rhetoric comes as part of a Kremlin campaign to reassert Russian power and roll back American gains since the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Putin has long been irked that NATO, America’s original anti-Soviet alliance, absorbed most of the former Warsaw Pact countries in Eastern Europe and expanded right up to Russia’s borders in the Baltic republics of Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. In October, he issued a list of specific demands to the United States, including the end of all anti-Russia sanctions, the rollback of NATO, and compensation to Russia.

While these demands might seem crazy from an American perspective, they form a negotiating position. If Putin can create a rash of new facts on the ground in a hurry, before Obama’s successor gets installed in the White House, then his agenda will have to be taken more seriously.

The Russian leader could try to put an incoming US president on the defensive by provoking a crisis with the Baltic republics. (Trump has made comments during the campaign to suggest if he were president, he might not honor NATO’s commitment to defend the vulnerable Baltics from Russia.)

Putin could also scrap more of the US-Russia nuclear agreements, in order to shift the conflict with Washington away from conventional wars, like the fights in Syria and Ukraine, and onto the much scarier plane of nuclear war. Since 1991, we’ve grown inured to the risk of Armageddon, a fear that Putin seems eager to revive.

A really shocking November maneuver could take surprising forms. Putin could threaten to deploy nuclear-capable weapons to Syria or Cuba. He could aggressively deploy his navy and air force in close proximity to NATO. He could send flash-mob invaders into the Baltics and annex territory, like he did in Crimea.

DISRUPTORS WITH A long-term agenda have the biggest incentive to strike during the lame-duck period, since they are trying not only to provoke a reaction but set the stage for a later negotiation. That’s why the lame-duck period is not such fertile ground for nihilist terrorist groups whose main goal is to goad the US leadership into overreaction; they are more likely to want to target a early-term president.

In the Middle East, some of the usual culprits are also unlikely to act. Israel has had a testy relationship with Obama. But it considers Clinton a stalwart supporter of Israeli government policy, and Trump, despite some boisterous comments during the campaign, has gone out of his way to reassure boosters of the Israeli government. Unlike in 2008, Israeli officials seem confident that they’ll get a more sympathetic ear in the next White House, so they’ll have little interest in major lame-duck period shifts with Gaza or along the borders with Lebanon and Syria.

On the contrary, Saudi Arabia has every reason to accelerate its ill-conceived war in Yemen, which the United States unwisely backed as a concession to a Saudi monarchy that felt sidelined by Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran. As the war crimes have piled up, Obama at last in October ordered a long-overdue review over American support for the Yemen war. Reading the tea leaves, Saudi Arabia’s leaders can expect the United States to curtail or even cut off military support in the near future. Certainly, the next US president will have a free hand to pull out of the ugly Yemen war.

This is precisely the most combustible recipe for a desperate November blitz. Knowing that it can’t win the war outright and install its preferred leader in Yemen, Saudi Arabia might seek to hobble its Yemen opponents as much as possible with more of the same sort of widespread bombing with which it has targeted Yemen’s political class and infrastructure.

Not all lame-duck foreign policy flare-ups occur in the Middle East. The main issues confronting the United States remain the same: countering great power threats, containing nuclear proliferation, and battling terrorism, most prominently from the Islamic State.

Beyond the already boiling Middle East, there are other pressure points ripe for November surprises. In the South China Sea and its disputed islands, for instance, China has been pushing hard. It could make a further show of force, further entrenching its claims over what promises to be a focal point of dangerous great-power competition on the next president’s watch.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, the man who proudly compared himself to Hitler on account of his campaign to capture or kill millions of drug addicts, has said Obama can “go to hell” while threatening to “break up” with America. America’s Asia strategy relies on a unified, concerted counterweight to China — a carefully crafted entente that Duterte seems gleefully willing to shatter. A break in the US-Philippines relationship could drastically shift the balance of power in Asia. Duterte seems both reckless and shrewd enough to use a realistic breakup threat as leverage to force America to back down on its threats to punish him for his endemic abuse of human rights.

The lame-duck period invites malingerers, spoilers, rogues, and all manner of American rivals to fire shots across Washington’s bow. North Korea already periodically rattles the world with rocket launches and nuclear tests. It might feel the need to do so again now as a warning to Clinton or Trump.

WHAT CAN OBAMA do to get out ahead of these kind of prospective lame-duck period spoiler moves? Are there spoiler moves of his own that Obama could make, as a gift to America — or his successor?

In foreign affairs, Obama has been systematic and cerebral; he has tried to follow the policies that he laid out in his own speeches. He has also been very open with his frustrations about annoying allies that pursue their own ends and flout their American patron.

Free to pursue his conscience without risk in any future election campaign, Obama could make unilateral foreign policy moves that could catch America’s rivals off guard. For an opportunist, the lame-duck period cuts both ways.

For starters, Obama could sow heartache among whiny allies, cutting or freezing military aid that foreign governments would then have to earn back, through better cooperation, from Obama’s successor. The list is long and insalubrious, but Obama could take some of the political blowback for himself and turn the tables on entitled clients who act like aid and weapons from America are their birthright.

Saudi Arabia relies exclusively on America’s defense umbrella for its security. Any threat that it could seek weapons elsewhere, such as Russia or China, rings hollow, since its entire defense establishment is built on American hardware, resupply, and trainers. Washington could freeze arms sales, pending a lengthy review of rights violations in the Yemen war — pointedly reminding its brittle Gulf ally that Washington also holds cards in the relationship.

Other relationships ready for “right-sizing” include Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and Turkey. In each case, Obama could slow down or stall existing aid, on entirely procedural grounds, to remind each one of these sometimes quarrelsome client states that they need to earn their special relationships with the United States, rather than straining them.

This year’s ugly presidential campaign has stoked racism and xenophobia. As a result, the United States, already a malingerer when it comes to admitting refugees, has lagged worldwide. Obama raised America’s tiny quota, but it remains at symbolic levels, with few slots reserved for people displaced from key trouble spots like Syria and Iraq.

Obama could rip a page out of the playbook of his Canadian colleague Justin Trudeau, who promised to admit 25,000 Syrian refugees in his first two months in office. (It took him four months, but he accomplished the target in February.) Surely if Canada can manage such a feat, so can the far larger United States.

An Obama November surprise to admit refugees would be a generous about-face. It would shift politics away from fear of terrorism to embrace America’s melting-pot identity — and create a fait accompli for his successor. Even if Clinton wins, she would be unlikely to take such an initiative in the face of political challenges from the anti-immigrant right, which Trump exemplifies.

Obama could also erase a blot on America’s reputation by closing the prison at Guantanamo Bay, where 61 detainees — many of them held indefinitely and without charge — languish in legal limbo. America’s island prison is the most egregious symbol of the post-9/11 overreaction, which enshrined the notion of an endless war against terrorism, a tactic which will never disappear from the face of the earth. Obama promised in his 2008 campaign to close Guantanamo, but his determination was foiled by the complicated politics and logistics. However, he has the executive authority to close this loophole in America’s constitutional rule of law. Come Nov. 8, he’ll have the political freedom to do it.

Washington can even use the lame-duck leverage in sectors removed from the usual business of war and peace, like the airline industry. The United States is in trade talks right now with the United Arab Emirates and Qatar over a persistent source of discord: the subsidies that give those countries’ airlines a competitive edge over US airlines. There’s now reportedly a move afoot by the Gulf monarchies to take whatever deal they can get now from Obama’s State Department. After a campaign that raised protectionist ire and anger about unfair advantages to foreign competitors, there would be increased scrutiny on those subsidies.

Powerful governments with nothing to lose can be dangerous. And as we’ve painfully learned over the last year, uncertainty in international relations can breed violent and destabilizing competition for power.

The 10 weeks that follow American Election Day — the single most important date on the calendars of schemers and plotters worldwide — offer peril. For a departing American president who’s looking toward the history books, they also offer opportunity.

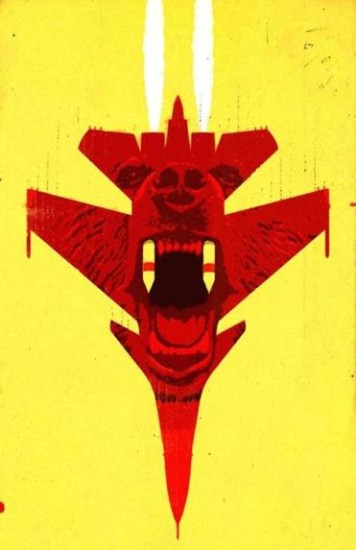

Putin’s crushing strategy in Syria

Illustration: RICHARD MIA FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

LATAKIA, SYRIA

WHEN RUSSIAN JETS started bombing Syrian insurgents, it was no surprise that fans of President Bashar Assad felt buoyed. What was surprising was the outsized, even over-the-top expectations placed on Russian help.

“They’re not like the Americans,” explained a Syrian government official responsible for escorting journalists around the coastal city of Latakia. “When they get involved, they do it all the way.”

Naturally, tired supporters of the Assad regime are susceptible to any optimistic thread they can cling to after five years of a war that the government was decisively losing when the Russians unveiled a major military intervention in October.

Russian fever isn’t entirely driven by hope and ignorance. Many of the Syrians cheering the Russian intervention know Moscow well.

A fluent Russian speaker, the bureaucrat in Latakia had spent nearly a decade in Moscow studying and working. Much of Syria’s military and Ba’ath Party elite trained in Moscow, steeped in Soviet-era military and political doctrine, along with an unapologetic culture of tough-talking secular nationalism (there’s also a shared affinity for vodka or other spirits).

The Russians have announced that they will partner with the French to fight the Islamic State in the wake of the terrorist attacks in Paris. But beyond new friendships forged in the wake of the Paris massacre and the downing of a Russian charter flight over the Sinai in October, Moscow’s strategic interest in Syria is longstanding and vital to its interest.

The world reaction to the Russian offensive in Syria has been as much about perception as military reality. Putin, according to Russian analysts who carefully study his policy, wants more than anything else to reassert Russia’s role as a high-stakes player in the international system.

Sure, they say, he wants to reduce the heat from his invasion of Ukraine, and he wants to keep a loyal client in place in Syria, but most of all, he wants Russia’s Great Power role back.

For all the mythmaking and propaganda, there is a powerful historical context to Russia’s latest foreign military intervention. Like all states that try to project force beyond their borders, Putin’s Russia faces limits. But those limits differ markedly from those that doomed America’s recent fiascoes in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The spectacular international attacks by Islamic State militants against targets in the Sinai, Beirut, and Paris have reminded Western powers of the other interests at stake beyond a resurgent Russia and a prickly Iran. Until now, Russia’s new role in Syria has stymied the West, impinging on its air campaign against ISIS and all but eliminating the possibility of an anti-Assad no-fly zone.

Russia’s blitzkrieg in Syria might have only tilted the conflict in Assad’s favor, with no prospect of securing an outright win for the dictator in Damascus — and yet, that might be more than enough to achieve Russia’s limited objectives.

As a result of a bold, arguably cynical, gamble, Putin might just get what he wants.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER WORLD WAR II, the Soviet Union quashed armed insurgencies in many of its newly annexed republics, including Western Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Western Belarus.

Those early campaigns shaped a distinct Soviet approach to counterinsurgency, according to Mark Kramer, program director of the Project on Cold War Studies at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

The United States was at the same time developing its own theories about winning over local populations, which underpinned the doctrine of “population-centric” counterinsurgency that ultimately failed to accomplish American aims in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s.

The Soviet Union, on the other hand, developed what Kramer calls “enemy-centric” counterinsurgency: Kill the enemy, establish control, and only then sort out questions about governance and legitimacy.

Harsh tactics worked for the Soviets. Kramer quotes the future Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev directing his agents in 1945 Ukraine to use unbridled violence against insurrectionists: “The people will know: For one of ours, we will take out a hundred of theirs! You must make your enemies fear you, and your friends respect you.”

In 1956, the Soviets used similar tactics to crush an uprising in Hungary. Despite the widespread perception of failure in Afghanistan, says Kramer, the Soviets had successfully propped up their local client, at great but sustainable cost, until Mikhail Gorbachev decided to repudiate the war there — just before US antiaircraft missiles arrived in the theater.

Vladimir Putin, insulated from political pressure, has drawn on this history to craft a brutal approach to counterinsurgency.

The first post-Soviet president, Boris Yeltsin, presided over the weakening of the Russian military and a desultory defeat at the hands of rebels in the first Chechen war of 1994 to 1996. As Putin prepared for a second Chechen war, in 1999, he used political coercion to guarantee friendly media coverage from Russian television and erase any meaningful political dissent over the war.

“During Putin’s [first] presidency, the Russian government was able to quell the insurgency in Chechnya without, in any way, having ‘won hearts and minds,’ ” Kramer wrote in a 2007 assessment after the Chechen war was provisionally settled in Putin’s favor. “Historically, governments have often been successful in using ruthless violence to crush large and determined insurgencies, at least if the rulers’ time horizons are focused on the short to medium term.”

Kramer compares Putin’s approach to that of Saddam Hussein, Stalin, and Hitler. It also seems very similar to Bashar Assad’s strategy today in Syria.

With no need to worry about public opinion, Putin’s counterinsurgency could kill countless Chechen civilians. When retaliatory Chechen terrorist attacks killed hundreds of Russian civilians in theaters and schools, Putin’s campaign only gained support. Russia’s flawed strategy in Chechnya ultimately created an outcome that worked for Putin.

“Historically, insurgencies tend to last eight to ten years, and most of the time Soviet and Russian forces have achieved their goals,” Kramer said.

Today Russia can’t entirely ignore international opinion, which has run strongly against its intervention in Ukraine. Doubling down in Syria, it turns out, has created the possibility of an exit strategy.

“Putin’s trying to change the topic from Ukraine, and maybe he’s been successful on that,” said Thomas de Waal, a scholar at Carnegie Europe who wrote a book about the Chechen war and closely follows Russian policy.

The style that Russia has honed — “overwhelming force as your basic strategy,” de Waal said — fits well with Assad’s merciless shelling of opposition areas. “You treat every enemy city as Berlin, and you pulverize it,” de Waal said, describing Putin’s approach to insurgencies. “There’s no subtlety, no regard for collateral damage or civilians.”

STATE MEDIA IN SYRIA has continued to herald the Russian intervention as a massive game-changer, but on-the-ground realities have already brought short initial expectations. Early predictions of a rout foundered when the Russians encountered resistance.

Anti-Assad forces, as any longtime observer of the conflict would have predicted, continue to fight back hard. Local militants defending their communities rarely quit; when they are defeated, victory can require months or years of fighting. In response to Russia’s escalation, the United States and other foreign backers of anti-Assad militias opened the spigot of aid including antitank missiles. Jihadists are equally formidable foes.

Assad appeared to be on the losing end of a stalemate before the Russian intervention. A major coordinated push by Russia, Iran, and the Syrian government could turn the momentum the other way, but analysts of the conflict doubt there’s any prospect of an outright victory.

Once the dust settles, the Syrian government will still suffer from the same manpower shortage that has plagued its efforts, and antigovernment forces will remain entrenched, said Noah Bonsey, Syria analyst for International Crisis Group. With Russian help, the government has gained ground around Aleppo but has lost some around Hama.

“In real military terms, it gets us right about to where we were before the intervention,” Bonsey said. “We haven’t seen any significant breakthroughs.”

Some of the closest followers of the Kremlin’s designs in Syria and the wider Middle East, like Russian analyst Nikolay Kozhanov, argue that Putin was never aiming for a military solution in Syria but only to better position Russia in the diplomatic great game.

Another Russian analyst, Nadia Arbatova, a political scientist at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations, said Russia wants to regain influence by convincing the United States and other Western powers to join Moscow in a counterterrorism alliance. She doesn’t think the Kremlin has carefully studied its own history in foreign interventions. The Syrian intervention, in her view, is less about Syria than it is about showing the West that Moscow can project global power again.

“For the first time after the collapse of the USSR, Russia is conducting a big military operation outside the post-Soviet space,” Arbatova said. “Hence Russia is not just a regional center but a world power.”

The most important lesson from Russia’s counterinsurgency history might be its Machiavellian reading of the politics involved. Moscow, when it succeeds, lays out clear aims and then methodically deploys force and political tools to reach them.

In Syria, Russia has sided with a rigid regime that has demonstrated a rigid unwillingness to entertain any compromise at all with an uprising that has engulfed most of the country. Its main partner is the Islamic Republic of Iran, whose political culture, regional interests, and long-term goals differ greatly from Moscow’s.

Putin might find his Syrian adventure meets even more obstacles than his increasingly bold interventions in Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine. Although each of Putin’s previous interventions carried an increasingly costly international price tag, all of them came in the former Soviet space, in an arena where no outside power can freely maneuver.

Syria is a different story altogether, a civil war saturated with foreign proxies. Russia is intervening on behalf of a minority regime that has already been fighting at maximum capacity. On the other side is a fractured rebellion, trapped between government forces and the Islamic State — which despite its considerable failings and only tepid backing from the United States has managed to keep Damascus on the defensive.

In government-controlled areas, Assad supporters have fully swallowed the enthusiastic propaganda about the intervention, peddled by Moscow and Damascus both.

“It won’t be long now, it’s going to finish soon,” said one volunteer fighter for the Syrian regime, a 38-year-old militiamen in the National Defense Forces with the word “love” tattooed on his forearm, sipping juice at a seaside café near his base. By next summer, he predicted, the war would be over, thanks to Moscow. “There will be strong forces of Russians, Iraqis, and Syrians fighting together. We will be strong. We are at end of the crisis.”

History suggests a more pessimistic forecast. Russia might get lucky, winning a diplomatic settlement at an instant when the Islamic State’s attacks have prompted a confluence of interests. More likely, however, Moscow will settle in for a decade of crushing counterinsurgency in Syria, against foes with considerable legitimacy, who represent a possible majority of Syrians and have the backing of some of the world’s richest and most powerful states. Russia has the resources and security to wait and see how the long game plays out, but it’s unlikely to end with either the blitzkrieg for which Assad’s fighters yearn or the hasty and favorable political settlement that Putin’s diplomats are pushing.

Assad pays respects to Putin

Syria’s president paid a visit to Moscow this week, maybe to say thank you, maybe to pay fealty to a sponsor, maybe to hear some requests. Some compared the visit to the obligatory calls Lebanese presidents used to have to pay the Assads in Damascus. PRI’s The World talked to Neil McFarquhar about the visit, and then asked me about the lives of everyday Syrians I met on my visit to Syria earlier this month. You can listen here.

“There’s a sense of relief that the cavalry coming from Moscow is going to be much closer to the Syrian elite’s way of life than the Iranians who had been rescuing them until now,” Cambanis says.

For evidence of the comradery, consider the affectionate nickname Assad supporters have given Putin — “Abu Ali.”

“It’s a way of saying this guy is one of us, he’s going to be the godfather of our victory, and he’s a little bit of an old-fashioned strongman.” Cambanis says. “It’s sort of silly, propagandistic sycophancy. On the other hand, it reflects this thirst for an outside savior.”

What line did Putin cross in Crimea?

[The Internationalist column published in the The Boston Globe Ideas.]

WHAT HAPPENED IN UKRAINE over the past month left even veteran policy-watchers shaking their heads. One day, citizens were serving tea to the heroic demonstrators in Kiev’s Euromaidan, united against an authoritarian president. Almost the next, anonymous special forces fighters in balaclavas were swarming Crimea, answering to no known leader or government, while Europe and the United States grasped in vain for ways to influence events.

Within days, the population of Crimea had voted in a hastily organized referendum to join Russia, and Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, had signed the annexation treaty formally absorbing the strategic peninsula into his nation.

As the dust settles, Western leaders have had to come to terms not only with a new division of Ukraine, but its unsettling implications for how the world works. Part of the shock is in Putin’s tactics, which blended an old-fashioned invasion with some degree of democratic process within the region, and added a dollop of modern insurgent strategies for good measure.

Vladimir Putin at the Plesetsk cosmodrome launch site in northern Russia./PRESIDENTIAL PRESS SERVICE VIA REUTERS

But when policy specialists look at the results, they see a starker turning point. Putin’s annexation of the Crimea is a break in the order that America and its allies have come to rely on since the end of the Cold War—namely, one in which major powers only intervene militarily when they have an international consensus on their side, or failing that, when they’re not crossing a rival power’s red lines. It is a balance that has kept the world free of confrontations between its most powerful militaries, and which has, in particular, given the United States, as the most powerful superpower of all, an unusually wide range of motion in the world. As it crumbles, it has left policymakers scrambling to figure out both how to respond, and just how far an emboldened Russia might go.

***

“WE LIVE IN A DIFFERENT WORLD than we did less than a month ago,” NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen said in March. Ukraine could witness more fighting, he warned; the conflict could also spread to other countries on Russia’s borders.

Up until the Crimea crisis began, the world we lived in looked more predictable. The fall of the Berlin Wall a quarter century ago ushered in an era of international comity and institution building not seen since the birth of the United Nations in 1945. International trade agreements proliferated at a dizzying speed. NATO quickly expanded into the heart of the former Soviet bloc, and lawyers designed an International Criminal Court to punish war crimes and constrain state interests.

Only small-to-middling powers like Iran, Israel, and North Korea ignored the conventions of the age of integration and humanitarianism—and their actions only had regional impact, never posing a global strategic threat. The largest powers—the United States, Russia, and China—abided by what amounted to an international gentleman’s agreement not to use their military for direct territorial gains or to meddle in a rival’s immediate sphere of influence. European powers, through NATO, adopted a defensive crouch. The United States, as the world’s dominant military and economic power, maintained the most freedom to act unilaterally, as long as it steered clear of confrontation with Russia or China. It carefully sought international support for its military interventions, even building a “Coalition of the Willing” for its 2003 invasion of Iraq, which was not approved by the United Nations. The Iraq war grated at other world powers that couldn’t embark on military adventures of their own; but despite the irritation the United States provoked, American policymakers and strategists felt confident that the United States was obeying the unspoken rules.

If the world community has seemed bewildered by how to respond to Putin’s moves in Crimea over the last month, it’s because Russia has so abruptly interrupted this narrative. Using Russia’s incontestable military might, with the backing of Ukrainians in a subset of that country, he took over a chunk of territory featuring the valuable warm-water port of Sevastopol. The boldness of this move left behind the sanctions and other delicate moves that have become established as persuasive tactics. Suddenly, it seemed, there was no way to halt Russia without outright war.

Some analysts say that Putin appears to have identified a loophole in the post-Cold War world. The sole superpower, the United States, likes to put problems in neat, separate categories that can be dealt with by the military, by police action or by international institutions. When a problem blurs those boundaries—pirates on the high seas, drug cartels with submarines and military-grade weapons—Western governments don’t know what to do. Today, international norms and institutions aren’t configured to react quickly to a legitimate great power willing to use force to get what it wants.

“We have these paradigms in the West about what’s considered policing, and what’s considered warfare, and Putin is riding right up the middle of that,” said Janine Davidson, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former US Air Force officer who believes that Putin’s actions will force the United States to update its approach to modern warfare. “What he’s doing is very clever.”

For obvious reasons, a central concern is how Putin might make use of his Crimean playbook next. He could, for example, try to engineer an ethnic provocation, or a supposedly spontaneous uprising, in any of the near-Russian republics that threatens to ally too closely with the West. Mark Kramer, director of Harvard University’s Project on Cold War Studies, said that Putin has “enunciated his own doctrine of preemptive intervention on behalf of Russian communities in neighboring countries.”

There have been intimations of this approach before. In 2008, Russian infantry pushed into two enclaves in neighboring Georgia, citing claims—which later proved false—that thousands of ethnic Russians were being massacred. Russia quickly routed the Georgian military and took over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Today the disputed enclaves hover in a sort of twilight zone; they’ve declared independence but were recognized only by Moscow and a few of its allies. Ever since then, Georgian politicians have warned that Russia might do the same thing again: The country could seize a land corridor to Armenia, or try to absorb Moldova, the rest of Ukraine, or even the Baltic States, the only former Soviet Republics to join both NATO and the European Union.

Others see Putin’s reach as limited at best to places where meaningful military resistance is absent and state control weak. Even in Ukraine, Russia experts say, Putin seemed content to wield influence through friendly leaders until protests ran the Ukrainian president out of town and left a power vacuum that alarmed Moscow. Graham, the former Bush administration official, said it would be a long shot for Putin to move his military into other republics: There are few places with Crimea’s combination of an ethnic Russian enclave, an absence of state authority, and little risk of Western intervention.

The larger worry, of course, is who else might want to follow Russia’s example. China is the clearest concern, and from time to time has shown signs of trying to throw its weight around its region, especially in disputed areas of the South China Sea. But so far it has been Chinese fishing boats and coast guard vessels harassing foreign fishermen, with the Chinese navy carefully staying away in order not to trigger a military response. For the moment, at least, Putin seems willing to upend this delicately balanced world order on his own.

***

THE INTERNATIONAL community’s flat-footed response in Crimea raises clear questions: What should the United States and its allies do if this kind of land grab happens again—and is there a way to prevent such moves in the first place?

“This is a new period that calls for a new strategy,” said Michael A. McFaul, who stepped down as US ambassador to Russia a few weeks before the Crimea crisis. “Putin has made it clear that he doesn’t care what the West thinks.”

So far the international response has entailed soft power pressure that is designed to have an effect over the long term. The United States and some European governments have instated limited economic sanctions targeting some of Putin’s close advisers, and Russia has been kicked out of the G-8. There’s talk of reinvigorating NATO to discourage Putin from further adventurism. So far, though, NATO has turned out to be a blunt instrument: great for unifying its members to respond to a direct attack, but clumsy at projecting power beyond its boundaries. As Putin reorients away from the West and toward a Greater Russia, it remains to be seen whether soft-power deterrents matter to him at all.

Beyond these immediate measures, American experts are surprisingly short on specific suggestions about what more to do, perhaps because it’s been so long since they’ve had to contemplate a major rival engaging in such aggressive behavior. At the hawkish end, people like Davidson worry that Putin could repeat his expansion unless he sees a clear threat of military intervention to stop him. She thinks the United States and NATO ought to place advisers and hardware in the former Soviet republics, creating arrangements that signal Western military commitment. It’s a delicate dance, she said; the West has to be careful not to provoke further aggression while creating enough uncertainty to deter Putin.

Other observers in the field have made more modest economic proposals. Some have urged major investment in the economies of contested countries like Ukraine and Moldova, at the scale of the post-World War II Marshall Plan, and a long-term plan to wean Western Europe off Russian natural gas supplies, through which Moscow has gained enormous leverage, especially over Germany.

Davidson, however, believes that a deeper rethink is necessary, so that the United States won’t get tied up in knots or outflanked every time a powerful nation like Russia uses the stealthy¸ unpredictable tactics of non-state actors to pursue its goals. “We need to look at our definitions of military and law enforcement,” she said. “What’s a crime? What’s an aggressive act that requires a military response?”

McFaul, the former ambassador, said we’re in for a new age of confrontation because of Putin’s choices, and both the United States and Russia will find it more difficult to achieve their goals. In retrospect, he said, we’ll realize that the first decades after the Cold War offered a unique kind of safety, a de facto moratorium on Great Power hardball. That lull now seems to be over.

“It’s a tragic moment,” McFaul said.