Putin’s crushing strategy in Syria

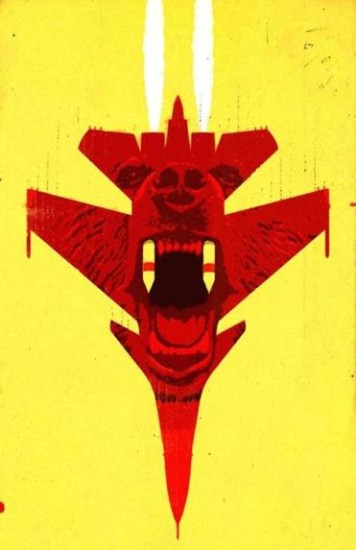

Illustration: RICHARD MIA FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

LATAKIA, SYRIA

WHEN RUSSIAN JETS started bombing Syrian insurgents, it was no surprise that fans of President Bashar Assad felt buoyed. What was surprising was the outsized, even over-the-top expectations placed on Russian help.

“They’re not like the Americans,” explained a Syrian government official responsible for escorting journalists around the coastal city of Latakia. “When they get involved, they do it all the way.”

Naturally, tired supporters of the Assad regime are susceptible to any optimistic thread they can cling to after five years of a war that the government was decisively losing when the Russians unveiled a major military intervention in October.

Russian fever isn’t entirely driven by hope and ignorance. Many of the Syrians cheering the Russian intervention know Moscow well.

A fluent Russian speaker, the bureaucrat in Latakia had spent nearly a decade in Moscow studying and working. Much of Syria’s military and Ba’ath Party elite trained in Moscow, steeped in Soviet-era military and political doctrine, along with an unapologetic culture of tough-talking secular nationalism (there’s also a shared affinity for vodka or other spirits).

The Russians have announced that they will partner with the French to fight the Islamic State in the wake of the terrorist attacks in Paris. But beyond new friendships forged in the wake of the Paris massacre and the downing of a Russian charter flight over the Sinai in October, Moscow’s strategic interest in Syria is longstanding and vital to its interest.

The world reaction to the Russian offensive in Syria has been as much about perception as military reality. Putin, according to Russian analysts who carefully study his policy, wants more than anything else to reassert Russia’s role as a high-stakes player in the international system.

Sure, they say, he wants to reduce the heat from his invasion of Ukraine, and he wants to keep a loyal client in place in Syria, but most of all, he wants Russia’s Great Power role back.

For all the mythmaking and propaganda, there is a powerful historical context to Russia’s latest foreign military intervention. Like all states that try to project force beyond their borders, Putin’s Russia faces limits. But those limits differ markedly from those that doomed America’s recent fiascoes in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The spectacular international attacks by Islamic State militants against targets in the Sinai, Beirut, and Paris have reminded Western powers of the other interests at stake beyond a resurgent Russia and a prickly Iran. Until now, Russia’s new role in Syria has stymied the West, impinging on its air campaign against ISIS and all but eliminating the possibility of an anti-Assad no-fly zone.

Russia’s blitzkrieg in Syria might have only tilted the conflict in Assad’s favor, with no prospect of securing an outright win for the dictator in Damascus — and yet, that might be more than enough to achieve Russia’s limited objectives.

As a result of a bold, arguably cynical, gamble, Putin might just get what he wants.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER WORLD WAR II, the Soviet Union quashed armed insurgencies in many of its newly annexed republics, including Western Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Western Belarus.

Those early campaigns shaped a distinct Soviet approach to counterinsurgency, according to Mark Kramer, program director of the Project on Cold War Studies at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

The United States was at the same time developing its own theories about winning over local populations, which underpinned the doctrine of “population-centric” counterinsurgency that ultimately failed to accomplish American aims in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s.

The Soviet Union, on the other hand, developed what Kramer calls “enemy-centric” counterinsurgency: Kill the enemy, establish control, and only then sort out questions about governance and legitimacy.

Harsh tactics worked for the Soviets. Kramer quotes the future Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev directing his agents in 1945 Ukraine to use unbridled violence against insurrectionists: “The people will know: For one of ours, we will take out a hundred of theirs! You must make your enemies fear you, and your friends respect you.”

In 1956, the Soviets used similar tactics to crush an uprising in Hungary. Despite the widespread perception of failure in Afghanistan, says Kramer, the Soviets had successfully propped up their local client, at great but sustainable cost, until Mikhail Gorbachev decided to repudiate the war there — just before US antiaircraft missiles arrived in the theater.

Vladimir Putin, insulated from political pressure, has drawn on this history to craft a brutal approach to counterinsurgency.

The first post-Soviet president, Boris Yeltsin, presided over the weakening of the Russian military and a desultory defeat at the hands of rebels in the first Chechen war of 1994 to 1996. As Putin prepared for a second Chechen war, in 1999, he used political coercion to guarantee friendly media coverage from Russian television and erase any meaningful political dissent over the war.

“During Putin’s [first] presidency, the Russian government was able to quell the insurgency in Chechnya without, in any way, having ‘won hearts and minds,’ ” Kramer wrote in a 2007 assessment after the Chechen war was provisionally settled in Putin’s favor. “Historically, governments have often been successful in using ruthless violence to crush large and determined insurgencies, at least if the rulers’ time horizons are focused on the short to medium term.”

Kramer compares Putin’s approach to that of Saddam Hussein, Stalin, and Hitler. It also seems very similar to Bashar Assad’s strategy today in Syria.

With no need to worry about public opinion, Putin’s counterinsurgency could kill countless Chechen civilians. When retaliatory Chechen terrorist attacks killed hundreds of Russian civilians in theaters and schools, Putin’s campaign only gained support. Russia’s flawed strategy in Chechnya ultimately created an outcome that worked for Putin.

“Historically, insurgencies tend to last eight to ten years, and most of the time Soviet and Russian forces have achieved their goals,” Kramer said.

Today Russia can’t entirely ignore international opinion, which has run strongly against its intervention in Ukraine. Doubling down in Syria, it turns out, has created the possibility of an exit strategy.

“Putin’s trying to change the topic from Ukraine, and maybe he’s been successful on that,” said Thomas de Waal, a scholar at Carnegie Europe who wrote a book about the Chechen war and closely follows Russian policy.

The style that Russia has honed — “overwhelming force as your basic strategy,” de Waal said — fits well with Assad’s merciless shelling of opposition areas. “You treat every enemy city as Berlin, and you pulverize it,” de Waal said, describing Putin’s approach to insurgencies. “There’s no subtlety, no regard for collateral damage or civilians.”

STATE MEDIA IN SYRIA has continued to herald the Russian intervention as a massive game-changer, but on-the-ground realities have already brought short initial expectations. Early predictions of a rout foundered when the Russians encountered resistance.

Anti-Assad forces, as any longtime observer of the conflict would have predicted, continue to fight back hard. Local militants defending their communities rarely quit; when they are defeated, victory can require months or years of fighting. In response to Russia’s escalation, the United States and other foreign backers of anti-Assad militias opened the spigot of aid including antitank missiles. Jihadists are equally formidable foes.

Assad appeared to be on the losing end of a stalemate before the Russian intervention. A major coordinated push by Russia, Iran, and the Syrian government could turn the momentum the other way, but analysts of the conflict doubt there’s any prospect of an outright victory.

Once the dust settles, the Syrian government will still suffer from the same manpower shortage that has plagued its efforts, and antigovernment forces will remain entrenched, said Noah Bonsey, Syria analyst for International Crisis Group. With Russian help, the government has gained ground around Aleppo but has lost some around Hama.

“In real military terms, it gets us right about to where we were before the intervention,” Bonsey said. “We haven’t seen any significant breakthroughs.”

Some of the closest followers of the Kremlin’s designs in Syria and the wider Middle East, like Russian analyst Nikolay Kozhanov, argue that Putin was never aiming for a military solution in Syria but only to better position Russia in the diplomatic great game.

Another Russian analyst, Nadia Arbatova, a political scientist at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations, said Russia wants to regain influence by convincing the United States and other Western powers to join Moscow in a counterterrorism alliance. She doesn’t think the Kremlin has carefully studied its own history in foreign interventions. The Syrian intervention, in her view, is less about Syria than it is about showing the West that Moscow can project global power again.

“For the first time after the collapse of the USSR, Russia is conducting a big military operation outside the post-Soviet space,” Arbatova said. “Hence Russia is not just a regional center but a world power.”

The most important lesson from Russia’s counterinsurgency history might be its Machiavellian reading of the politics involved. Moscow, when it succeeds, lays out clear aims and then methodically deploys force and political tools to reach them.

In Syria, Russia has sided with a rigid regime that has demonstrated a rigid unwillingness to entertain any compromise at all with an uprising that has engulfed most of the country. Its main partner is the Islamic Republic of Iran, whose political culture, regional interests, and long-term goals differ greatly from Moscow’s.

Putin might find his Syrian adventure meets even more obstacles than his increasingly bold interventions in Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine. Although each of Putin’s previous interventions carried an increasingly costly international price tag, all of them came in the former Soviet space, in an arena where no outside power can freely maneuver.

Syria is a different story altogether, a civil war saturated with foreign proxies. Russia is intervening on behalf of a minority regime that has already been fighting at maximum capacity. On the other side is a fractured rebellion, trapped between government forces and the Islamic State — which despite its considerable failings and only tepid backing from the United States has managed to keep Damascus on the defensive.

In government-controlled areas, Assad supporters have fully swallowed the enthusiastic propaganda about the intervention, peddled by Moscow and Damascus both.

“It won’t be long now, it’s going to finish soon,” said one volunteer fighter for the Syrian regime, a 38-year-old militiamen in the National Defense Forces with the word “love” tattooed on his forearm, sipping juice at a seaside café near his base. By next summer, he predicted, the war would be over, thanks to Moscow. “There will be strong forces of Russians, Iraqis, and Syrians fighting together. We will be strong. We are at end of the crisis.”

History suggests a more pessimistic forecast. Russia might get lucky, winning a diplomatic settlement at an instant when the Islamic State’s attacks have prompted a confluence of interests. More likely, however, Moscow will settle in for a decade of crushing counterinsurgency in Syria, against foes with considerable legitimacy, who represent a possible majority of Syrians and have the backing of some of the world’s richest and most powerful states. Russia has the resources and security to wait and see how the long game plays out, but it’s unlikely to end with either the blitzkrieg for which Assad’s fighters yearn or the hasty and favorable political settlement that Putin’s diplomats are pushing.

Cambanis vs. Cohen on Bloggingheads

My first foray onto Bloggingheads TV, with fellow TCF fellow Michael Cohen. Michael thinks COIN is “claptrap”; I think it was a decent idea taken too far. We’re both starting our discussion with a read of Fred Kaplan’s book The Insurgents, and our own long-standing argument about what went wrong in Iraq (and our mostly shared view of what went wrong in Afghanistan).

If you watch, you can hear in the background my kids apparently trying to tear down our house, directly upstairs from my head.

BONUS: CROWD-SOURCED TECH HELP? For some reason, I can’t figure out how to embed the video here. When I paste the embed code from BhTV in the post on WordPress, it just leaves the code as is. Any suggestions?

<embed type=”application/x-shockwave-flash” src=”http://static.bloggingheads.tv/ramon/_live/players/player_v5.2-licensed.swf” flashvars=”diavlogid=15077&file=http://bloggingheads.tv/playlist.php/15077/00:00/54:47&config=http://static.bloggingheads.tv/ramon/_live/files/2012/offsite_config.xml&topics=false” height=”288″ width=”380″ allowscriptaccess=”always” id=”bhtv15077″ name=”bhtv15077″></embed>

Kaplan and COIN: The Tweets

Fred Kaplan graciously took part in a Twitter conversation about his book, The Insurgents. He explained his concerns that the military remains confused about its mission, and expounded on his view that counterinsurgency doctrine is sometimes the right recipe and is not, as I suggested in a question, “snake oil,” or “the best way to fight a kind of war we should never fight.”

The tweets have been gathered here in what to the horror of those who care about grammar, is called a “storify,” v. trans. “to storify.”

Arrested Development: The Pentagon Going Forward

The Pentagon finally learned to embrace new ideas. Can its short-lived revolution in thinking survive the coming period of austerity and retrenchment? [Originally posted on The Blog of the Century.]

The American military has maintained global dominance in part by being all things to all people. Blessed with a Brobdingnagian budget, it has been able to prepare for all kinds of war, all at the same time. Faced now with cuts after a decade of open-handed war funding, the Pentagon has raised the alarm about readiness. The Joint Chiefs of Staff in a unanimous letter in January complained to the president that “we are on the brink of creating a hollow force.”

The debate over the size and mission of the military often obsesses about questions of degree: should the United States be able to fight two major wars at the same time? Should it design a force that can fight many small wars?

But this debate, driven by budget-hungry service chiefs and tradition-hemmed academics and think-tankers, might be ignoring a far more important turning point facing the Pentagon today, which has more to do with mindset than money. Can the Pentagon retain the one truly good thing it acquired along the way in the bungled war on terror, Afghanistan, and Iraq—a possibly short-lived ability to learn?

Fred Kaplan’s new book, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War, which I reviewed in the New York Times this Sunday, chronicles a chilling intellectual history of the officers who promoted counterinsurgency doctrine and eventually forced change among the Pentagon’s top brass. Kaplan is a skeptic, but his story reveals just how deeply hidebound the generals are, and how they were forced—through failure—to criticize themselves and adjust tactics.

Can this new mindset take root and become part of the Pentagon’s DNA, or is it destined to vanish as the generals who briefly dallied with self-awareness and adaptation now retrench around the common cause of budgetary self-preservation?

Listening to the current chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, isn’t reassuring. Half a decade ago in Baghdad he eschewed BS, acknowledging the burgeoning failure and once telling a group of us reporters bluntly that “there isn’t enough concrete in the hemisphere to make Baghdad safe.” Now he’s stumping for wild defense budgets based on a spurious claim that the world is more dangerous than ever before and that we face an infinite menu of threats. Dempsey’s about-face doesn’t bode well.

For all the pitfalls of the war on terror, a decade of coalition-building and counterinsurgency forced the military to adapt and open itself up to new methods with an alacrity not seen since World War II. It was a wrenching internal fight between rigid generals, abstract bureaucrats, and junior officers open to experimentation and self-criticism, which Kaplan documents in vivid detail.

In The Insurgents (published in January), Kaplan argues that the U.S. military, perhaps inadvertently, discovered on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan a new ability to learn. Now that the United States has moved away from those wars, Kaplan says, it is also throwing out what might be their only good legacy: imagination and flexibility in the Pentagon’s upper reaches.

His argument comes at a crucial time. President Obama last year ordered the Pentagon to cut off its budget for nation-building and long-term occupations of foreign lands—but he also instructed it to preserve the lessons it learned fighting counterinsurgencies in the Middle East. Many of the young officers who created a vogue around counterinsurgency in military circles grew just as dogmatic in their thinking as the older bureaucrats and officers who at first resisted new thinking, a sad process evident to any close observer of the slow failure of U.S. efforts in Afghanistan.

But they succeeded—at least in the last few years—at changing the military’s internal culture in ways far more consequential than the line item for a new bomber. They convinced the Pentagon to promote top generals who excelled in combat rather than those who had dutifully served in logistics and office posts. They reinvigorated the intellectual centers of military thinking, in particular the web of institutions from Fort Leavenworth to West Point that educate officers, write the military’s doctrine, and drive much of America’s strategic thinking. And they injected a strain of strikingly inventive utilitarianism—whatever works—into a vast defense bureaucracy that’s designed to protect fiefdoms rather than create new ideas.

Now, with the bloated war budgets ending and sequestration in site, a clear war of ideas is underway in the Pentagon: the old way, exemplified in the joint chiefs’ demand for big budgets, big weapons systems, and the same old lack of priorities, versus a fledgling new can-do culture that values the military’s ability to learn and adapt over its arsenal and size.

Let’s hope that creativity wins out. But I wouldn’t bet on it.

UPDATE: I debate The Insurgents and post-invasion Iraq with TCF fellow Michael Cohen. We’ll be on Bloggingheads TV on Wednesday.

How We Fight

Fred Kaplan’s Insurgents on David Petraeus

The American occupation of Iraq in its early years was a swamp of incompetence and self-delusion. The tales of hubris and reality-denial have already passed into folklore. Recent college graduates were tasked with rigging up a Western-style government. Some renegade military units blasted away at what they called “anti-Iraq Forces,” spurring an inchoate insurgency. Early on, Washington hailed the mess a glorious “mission accomplished.” Meanwhile, a “forgotten war” simmered to the east in Afghanistan. By the low standards of the time, common sense passed for great wisdom. Any American military officer willing to criticize his own tactics and question the viability of the mission brought a welcome breath of fresh air.

Most alarming was the atmosphere of intellectual dishonesty that swirled through the highest levels of America’s war on terror. The Pentagon banned American officers from using the word “insurgency” to describe the nationalist Iraqis who were killing them. The White House decided that if it refused to plan for an occupation, somehow the United States would slide off the hook for running Iraq. Ideas mattered, and many of the most egregious foul-ups of the era stemmed from abstract theories mindlessly applied to the real world.

There is no one better equipped to tell the story of those ideas — and their often hair-raising consequences — than Fred Kaplan, a rare combination of defense intellectual and pugnacious reporter. Kaplan writes Slate’s War Stories column, a must-read in security circles. He brings genuine expertise to his fine storytelling, with a doctorate from M.I.T., a government career in defense policy in the 1970s and three decades as a journalist. Kaplan knows the military world inside and out; better still, he has historical perspective. With “The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War,” he has written an authoritative, gripping and somewhat terrifying account of how the American military approached two major wars in the combustible Islamic world. He tells how it was grudgingly forced to adapt; how it then overreached; and how it now appears determined to discard as much as possible of what it learned and revert to its old ways.

Read the rest in The New York Times [subscription required].

Team America’s New Boss

The McChrystal story really spiced up the week, and brought the Afghan war into a really clear focus. Matthew Yglesias wrote a fantastic short essay at The Daily Beast about what General David Petraeus needs to do to succeed. In the piece, Yglesias tackles two potent and related points. First, he gives voice to the counter-narrative about the Iraq surge, arguing that what Petraeus accomplished there wasn’t “victory” or a “secure Iraq” but a political triumph – lowering America’s expectations enough that Iraq’s disappointing progress would satisfy Washington and allow an exit. Second, Yglesias argues that Afghanistan is literally unwinnable, but could be another “success” if Petraeus can work the same magical concoction: great PR, political jujitsu, and competent war management.

As he says in summation:

Petraeus could be just the man to do for Obama what he did for Bush: help reframe the problem and walk away from unrealistic goals while projecting determination and making things better in some small concrete ways.

Can Stan McChrystal’s Campaign Be Saved?

The nail-biting saga of General Stanley McChrystal’s Rolling Stone interview has riveted a wide audience whose interest in Afghanistan had otherwise flagged. Shortly we’ll know whether he keeps his job, and the hyperventilating will subside over civil-military relations (On life support? Healthier than ever?).

The nail-biting saga of General Stanley McChrystal’s Rolling Stone interview has riveted a wide audience whose interest in Afghanistan had otherwise flagged. Shortly we’ll know whether he keeps his job, and the hyperventilating will subside over civil-military relations (On life support? Healthier than ever?).

McChrystal’s personality aside, however, the American government needs to figure out something much more urgent and important: Is his counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan working? Based on what we’ve learned in the last year, can it work at all?

President Obama hired McChrystal to turn around a war that had stagnated. He was chosen to execute a nimble counterinsurgency strategy, a campaign designed to stabilize Afghanistan and win popular support among Afghanis, harnessing military, political and economic policy.

The prior strategy wasn’t working – the Taliban had made a dramatic comeback in the years since the original invasion in 2001. Even the most vocal proponents of counterinsurgency doctrine cautioned that it had no guarantee of succeeding. To give counterinsurgency a fighting chance might require more troops, money and time than the United States was willing and able to give. (That caveat presaged some early advocates’ current view that there were never enough resources tasked to make a COIN campaign viable.)

Now the U.S. is a year into McChrystal’s plan: the halfway point to the summer of 2011 when the surge is supposed to end and American troop numbers will be reduced. So much has gone off script, however, that it raises questions about whether McChrystal’s blueprint still applies.

- President Hamid Karzai has broken ranks, frequently attacking his U.S. patrons in public.

- The Taliban has gotten stronger militarily.

- The first showcase offensive in Marjah has so far failed to stabilize the town or deny the Taliban sanctuary there.

- This summer’s major showcase offensive in Taliban-dominated Kandahar has been indefinitely postponed.

- Pakistan has derailed efforts to negotiate with the Taliban, even arresting the Taliban’s number-two when he held clandestine meetings with the United Nations.

All these events don’t prove that the U.S. can’t achieve its aims in Afghanistan – but that’s the conclusion to which they’re beginning to point. Counterinsurgency defines the toolkit the military brings to the fight; it doesn’t actually answer the question of what America should do.

Over the next year, if it hopes to establish some lasting stable order in Afghanistan, America will need a far greater unity of effort between its generals, its diplomats, its special envoys, and its friends in the Afghan and Pakistani governments. With or without McChrystal, the United States will have to make course corrections in Afghanistan as the war unfolds.

Quick briefing materials

Fred Kaplan at Slate argues that McChrystal and his loose-lipped team reveal a war effort spinning of control.

Leslie H. Gelb at The Daily Beast argues that the Democratic Party suffers from a permanent culture clash with the military.

Andrew Exum writes a thoughtful post about whether the assumptions behind the current strategy in Afghanistan still hold up. He also struggles with the implications of firing/not firing McChrystal in these two posts.

In the “Is History Repeating Itself?” department we have Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s post-mortem on the last general fired from running the Afghan year, just about a year ago.

And finally, the Michael Hastings article in Rolling Stone that kicked off the fuss, and which – the scandal aside – raises pointed questions about whether the counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan makes any sense.